Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: An Analysis of Online Patient Testimony on Treatment Adherence

Abstract

1. Introduction

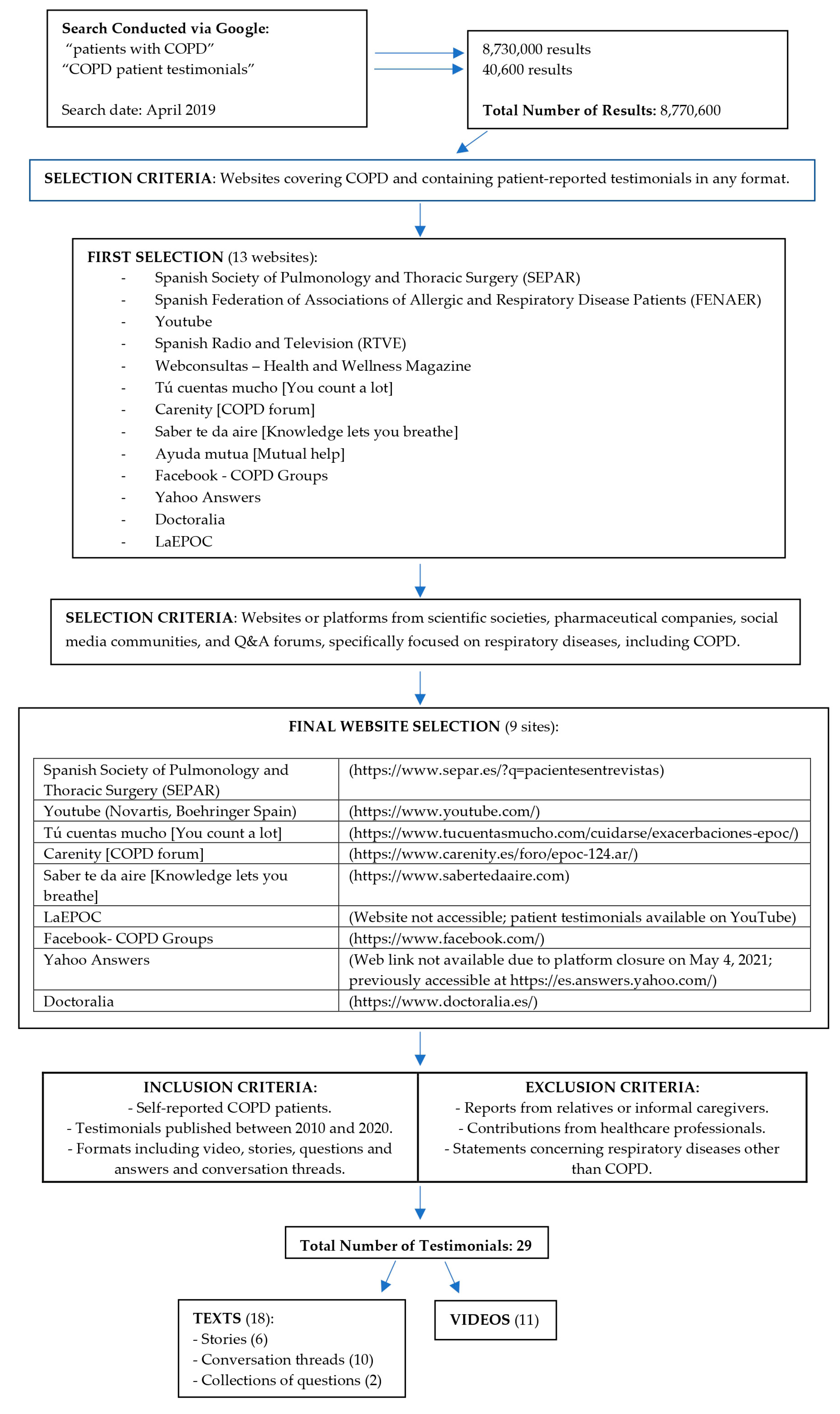

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Units of Analysis

2.3. Data Analysis

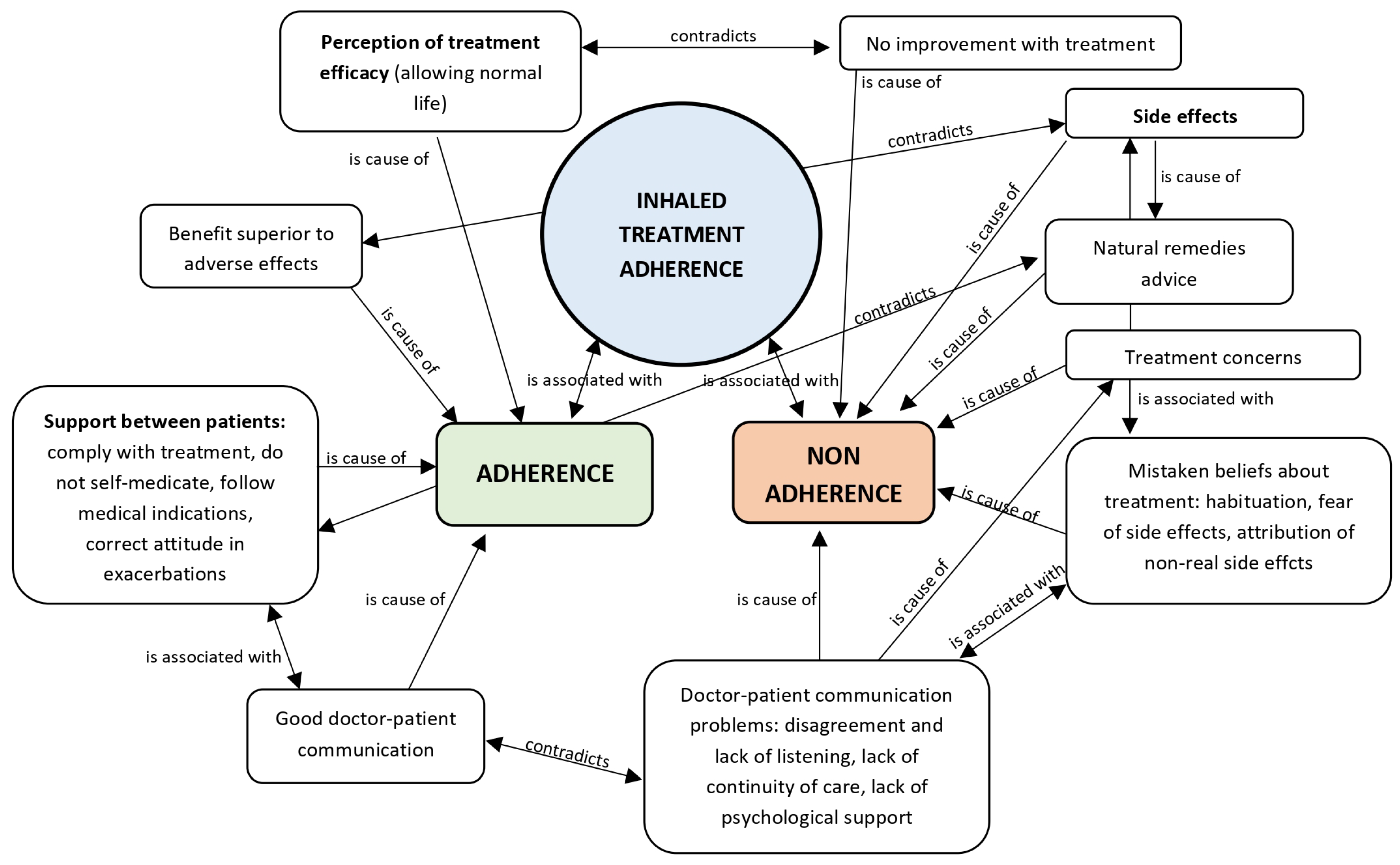

2.4. Qualitative Techniques

2.5. Methodological Rigor

3. Results

4. Discussion

- -

- Patient profile: Compared with COPD patients from other countries, Spanish COPD patients are predominantly male (54.1% vs. 41.6% female), with a mean age of 66.5 ± 10.9 years, a mean BMI of 27.4 ± 4.8, and 73% with a history of tobacco use (30.9% current smokers, 42.1% former smokers). They also tend to have a lower educational level and more comorbidities compared to non-COPD controls [53]. This profile is consistent with COPD populations in countries such as Greece [59], Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia, as reported in the POPE study [60].

- -

- -

- Adherence-related factors: Patient beliefs have also been associated with adherence. In a Chinese study, a strong correlation was observed between disease perception and inhaler adherence [65]. More broadly, a systematic review of English-language literature from high-income countries [66] indicated that adherence is influenced by patients’ beliefs and experiences regarding medications, satisfaction with treatment efficacy, concerns about side effects, personal circumstances, habits, health status, and relationships with healthcare professionals. Therefore, determinants of inhaled therapy adherence are multiple but do not differ significantly across countries.

- -

- Internet use: Internet use and social media engagement in Spain are comparable to the European average. According to Eurostat, in 2024, 58.16% of Europeans sought health information online, with Spain above the average at 69.63% [67]. Participation in social media (creating profiles, posting messages, and other contributions on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter) was 64.82% across Europe, with Spain at 64.70% [68]. Although data on Internet use specifically among Spanish COPD patients are limited, studies from other European countries indicate that COPD patients actively engage in the digital society, using the Internet to seek information and share experiences with peers, as reported in studies from Sweden [54], Germany, and Switzerland [45].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| TAI | Test of Adherence to Inhalers |

| INE | National Institute of Statistics |

Appendix A. Feedback on Conclusions

References

- Working Group of the GesEPOC. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary disease (COPD)—The Spanish COPD Guideline (GesEPOC). 2017 Version. [Guía de Práctica Clínica para el Diagnóstico y Tratamiento de Pacientes con Enfermedad Pulmonar Obstructiva Crónica (EPOC)–Guía Española de la EPOC (GesEPOC). Versión 2017]. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2017, 53 (Suppl. 1), 1–64. Available online: https://portal.guiasalud.es/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/gpc_593_gesepoc_compl.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Annual Report by the National Healthcare System 2023. Reports, Studies and Research. 2024. Ministry of Health 2024. [Informe Anual del Sistema Nacional de Salud 2023. Informes, Estudios e Investigación 2024. Ministerio de Sanidad 2024]. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/sisInfSanSNS/tablasEstadisticas/InfAnualSNS2023/INFORME_ANUAL_2023.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Miravitlles, M.; Ribera, A. Understanding the impact of symptoms on the burden of COPD. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, H.; Berterö, C.; Berg, K.; Jonasson, L.L. To live a life with COPD—The consequences of symptom burden. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2019, 14, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouza, E.; Alvar, A.; Almagro, P.; Alonso, T.; Ancochea, J.; Barbé, F.; Corbella, J.; Gracia, D.; Mascarós, E.; Melis, J.; et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Spain and the different aspects of its social impact: A multidisciplinary opinion document. Rev. Española Quimioter. 2020, 33, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Laird, P.N. Mental Models: Towards a Cognitive Science of Language, Inference and Conscientiousness; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal, H.; Diefenbach, M.; Leventhal, E.A. Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1992, 16, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achstetter, L.I.; Schultz, K.; Faller, H.; Schuler, M. Leventhal’s common-sense model and asthma control: Do illness representations predict success of an asthma rehabilitation? J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaife, S.L.; Brain, K.E.; Stevens, C.; Kurtidu, C.; Janes, S.M.; Waller, J. Development and psychometric testing of the self-regulatory questionnaire for lung cancer screening (SRQ-LCS). Psychol. Health 2021, 37, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, R.; Chapman, S.C.; Parham, R.; Freemantle, N.; Forbes, A.; Cooper, V. Understanding patients’ adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: A meta-analytic review of the Necessity-Concerns Framework. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.H.Y.; Katzer, C.B.; Pike, J.; Small, M.; Horne, R. Medication beliefs, adherence, and outcomes in people with asthma: The importance of treatment beliefs in understanding inhaled corticosteroid non adherence—A retrospective analysis of a real-world data set. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Glob. 2022, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Represas Represas, C.; Golpe Gómez, R.; Marcos Rodríguez, P.J.; Fernández García, A.; Torres Durán, M.; Pérez Ríos, M.; Ruano Raviña, A.; Fernández Villar, A. Knowledge of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) in the Galician Population: “CoñecEPOC” Study. Open Respir. Arch. 2021, 3, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja Cartón, L.A.; Muñoz Cobos, F.; Aguiar Leiva, V.; Navarro Guitart, C.; Barnestein Fonseca, P.; Leiva Fernández, F. Factors associated with therapeutic compliance in COPD. An analysis of the patient’s perspective. Med. Fam. Andal. 2021, 1, 11–24. Available online: https://www.samfyc.es/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/v22n1_original_cumpTerapEPOC.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Koehorst-ter Huurne, K.; Brusse-Keizer, M.; van der Valk, P.; Movig, K.; van der Palen, J.; Bode, C. Patient with underuse or overuse of inhaled corticosteroids have different perceptions and beliefs regarding COPD and inhaled medication. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 12, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borge, C.R.; Moum, T.; Puline Lein, M.; Austegard, E.L.; Wahl, A.K. Illness perception in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Scand. J. Psychol. 2014, 55, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaza, V.; López-Viña, A.; Entrenas, L.M.; Fernández-Rodríguez, C.; Melero, C.; Pérez-Llano, L.; Gutiérrez Pereyra, F.; Tarragona, E.; Palomino, R.; Cosio, B.G. Differences in Adherence and Non-Adherence Behaviour Patterns to Inhaler Devices Between COPD and Asthma Patients. COPD 2016, 13, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves Antonio, A.; Acuña Rodríguez, D.A. Use of websites or other sources of information for the prevention of chronic non-communicable diseases. [Uso de páginas Web u otros medios para la prevención de enfermedades crónicas no transmisibles]. Rev. Peru. Cienc. Salud 2021, 3, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle Rubio, M.; Rodríguez Hermosa, J.L.; Miravitlles, M.; López-Campos, J.L. Knowledge of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Presence of Chronic Respiratory Symptoms and Use of Spirometry Among the Spanish Population: CONOCEPOC 2019 study. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2021, 57, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvache Mateo, A.; López López, L.; Heredia Ciuró, A.; Martín Núñez, J.; Rodríguez Torres, J.; Ortiz Rubio, A.; Valenza, M.C. Efficacy of Web-Based Supportive Interventions in Quality of Life in COPD Patients, a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos de Aldana, M.S.; Moya Plata, D.; Mendoza Matajira, J.D.; Duran Niño, E.Y. Chronic non-communicable diseases and use of information and communication technology: Systematic review. [Las enfermedades crónicas no transmisibles y el uso de Tecnologías de información y comunicación: Revisión sistemática]. Rev. Cuid. 2014, 5, 661–669. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320502845_CHRONIC_NON-COMMUNICABLE_DISEASES_AND_USE_OF_INFORMATION_AND_COMMUNICATION_TECHNOLOGY_SYSTEMATIC_REVIEW (accessed on 7 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Carreres Candela, M.; Morera Harto, M.; Cuello Sanz, M.; Calderón Calvente, M.; Vicente Pastor, H.; Villota Bello, A. Social Media as a Means for Adherence to Care in Patients with Chronic Diseases. [Las Redes Sociales Como Medio para la Adherencia de los Cuidados en Pacientes con Enfermedades Crónicas]. Revista Sanitaria de Investigación, 28 March 2023. Available online: https://revistasanitariadeinvestigacion.com/las-redes-sociales-como-medio-para-la-adherencia-de-los-cuidados-en-pacientes-con-enfermedades-cronicas/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Partridge, M.R.; Dal Negro, R.W.; Olivieri, D. Understanding patients with asthma and COPD: Insights from a European study. Prim. Care Respir. J. 2011, 20, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apperson, A.; Stellefson, M.; Paige, S.R.; Chaney, B.H.; Chaney, J.D.; Wang, M.Q.; Mohan, A. Facebook groups on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Social media content analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.S.; Kostikas, K.; Gruenberger, J.B.; Shah, B.; Pathak, P.; Kaur, V.P.; Mudumby, A.; Sharma, R.; Gutzwiller, F.S. Patients’ perspectives on COPD: Findings from a social media listening study. ERJ Open Res. 2019, 5, 00128–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.G. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis; The Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basis of Qualitative Research. Techniques and Procedures to Develop the Grounded Theory [Bases de la Investigación Cualitativa. Técnicas y Procedimientos para Desarrollar la Teoría Fundamentada], 2nd ed.; CONTUS-Editorial Universidad de Antioquia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Homętowska, H.; Świątoniowska-Lonc, N.; Klekowski, J.; Chabowski, M.; Jankowska-Polańska, B. Treatment Adherence in Patients with Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugo-González, I.V.; Vega-Valero, C.Z.; González-Betanzos, F.; Robles-Montijo, S.; Fernández-Vega, M. Relationship between illness perception, treatment, adherence behaviors and asthma control; a mediation analysis. Neumol. Cirugía Tórax 2022, 81, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Argüello, J.; Blanco-Castillo, L.; Perea-Rangel, J.A.; Villareal Ríos, E.; Vargas Daza, E.R.; Galicia Rodríguez, L.; Martínez González, L. Disease belief, medication belief and adherence to treatment in patients with high blood pressure. Arch. Cardiol. México 2022, 92, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagès-Puigdemont, N.; Valverde-Merino, M.L. Medication Adherence: Modifiers and Improvement Strategies. ARS Pharm. 2018, 59, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, E.; Wensing, M.; De Smet, P.A.; Teichert, M. Exploring Patient’s Perspectives and Experiences After Start with Inhalation Maintenance Therapy: A Qualitative Theory-Based Study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2020, 14, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-de-Araújo, A.; Teixeira, P.; Hespanhol, V.; Correia-de-Sousa, J. COPD: Understanding patients’ adherence to inhaled medications. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2018, 13, 2767–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Cobos, F.; Acero Guasch, N.; Cuenca del Moral, R.; Barnestein Fonseca, P.; Leiva Fernández, F.; García Ruiz, A. How to live with COPD: Patient’s perception. Anal. Psicol. 2016, 32, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Rodríguez, M.; McMullan, I.; Warner, M.; Compton, C.H.; Tal-Singer, R.; Orlow, J.M.; Han, M.K. Perspectives on Treatment Decisions, Preferences, and Adherence and Long-Term Management in Asthma and COPD: A Qualitative Analysis of Patient, Caregiver, and Healthcare Provider Insights. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2024, 18, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.; Soliman, M.; McIvor, A.; Cave, A.; Cabrera, C. Understanding Patient Perspectives on Medication Adherence in Asthma: A Targeted Review of Qualitative Studies. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2020, 14, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persaud, P.N.; Tran, A.P.; Messner, D.; Thornton, J.D.; Williams, D.; Harper, L.J.; Tejwani, V. Perception of burden of oral and inhaled corticosteroid adverse effects on asthma-specific quality of life. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023, 131, 745–751.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madawala, S.; Warren, N.; Osadnik, C.; Barton, C. The primary care experience of adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). An interpretative phenomenological inquiry. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viejo-Bañuelos, J.L.; Sanchis, J. Inhaled terapy. The essential. [Terapia inhalada. Lo esencial]. Respir. Med. 2020, 13, 73–80. Available online: https://neumologiaysalud.es/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/medicina-respiratoria-13-3-.pdf#page=74 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Rodríguez Galarza, P.J.; Rodríguez Paredes, A.G. Doctor-Patient Relationship as a Risk Factor for Adherence to Pharmacological Treatment in Hypertensive Patients. [Relación Médico-Paciente Como Factor de Riesgo para Adherencia al Tratamiento Farmacológico en Pacientes Hipertensos]. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Peruana Los Andes, Huancayo, Peru, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro, H.M.; Cruz, A.J.E. Empathy, physician-patient relation and evidence-based medicine. Med. Interna México 2017, 33, 299–302. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0186-48662017000300299&lng=es (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Mujica Gómez, Y.A. Relationship Between Knowledge About Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Adherence to Inhalation Therapy in Patients at the Antonio Lorena Hospital in Cusco. [Relación Entre el Conocimiento Sobre la Enfermedad Pulmonar Obstructiva Crónica y la Adherencia a la Terapia Inhalatoria en Pacientes del Hospital Antonio Lorena del Cusco]. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Andina del Cusco, Cusco, Peru, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sigurgeirsdottir, J.; Halldorsdottir, S.; Arnardottir, R.H.; Gudmundsson, G.; Bjornsson, E.H. COPD patients’ experiences, self-reported needs, and needs-driven strategies to cope with self-management. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2019, 14, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasmarías-Ugarte, M.C.; Rubio-Garrido, P.; Jiménez-Herrera, M.; Bazo-Hernández, L.; Martorell-Poveda, M.A. Perception of Support Sources that Facilitate Adherence to Treatments [Percepción de las fuentes de apoyo que facilitan la adherencia a los tratamientos]. Enfermería Glob. 2023, 22, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.; Ogunbayo, O.J.; Newham, J.J.; Heslop Marshall, K.; Netts, P.; Hanratty, B.; Beyer, F.; Kaner, E. Qualitative systematic review of barriers and facilitators to self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Views of patients and healthcare professionals. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2018, 28, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimel, M.; Jat, H.; Basch, S.; Gutzwiller, F.S.; Biehl, V.; Eckert, J.H. Social Media Use in COPD Patients in Germany and Switzerland. Pneumologie 2021, 75, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Barberá, M.; Menárguez Puche, J.F.; Delsors Mérida-Nicolich, E.; Tello Royloa, C.; Sánchez Sánchez, J.A.; Alcántara Muñoz, P.A.; Soler Torroja, M. Online health information. Needs, expectations and quality assessment from the patients’ perspective. A qualitative study using focus group. [Información sanitaria en la red. Necesidades, expectativas y valoración de la calidad desde la perspectiva de los pacientes. Investigación cualitativa con grupos focales]. Rev. Clin. Med. Fam. 2021, 14, 131–139. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1699-695X2021000300003&lng=es (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Ali, L.; Fors, A.; Ekman, I. Need of support in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e1089–e1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, P.T.C.O.; Alves, K.Y.A.; Rodrigues, C.C.F.L.; Oliveira, L.V. Online data collection strategies used in qualitative research of the health field: A scoping review. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2020, 41, e20190297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, C.E.; Silverstein, L.B. Qualitative Data: An Introduction to Coding and Analysis; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ángel Pérez, D.A. Hermeneutics and research methods of Social Science. [La hermenéutica y los métodos de investigación en ciencias sociales]. Estud. Filos. 2011, 44, 9–37. Available online: https://revistas.udea.edu.co/index.php/estudios_de_filosofia/article/view/12633/11391 (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Roldán-Tovar, L.; Muñoz-Cobos, F.; Martos-Crespo, F. Internet as a data source in qualitative research in health sciences. Virtual Patient Communities. [Internet como fuente de datos en investigación cualitativa en ciencias de la salud. Comunidades virtuales de pacientes]. Index Enferm. 2023, 32, e13168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrero Ledesma, N.E.; Nájera, A.; Reolid-Martínez, R.E.; Escobar-Rabadán, F. Internet health information seeking by primary care patients. Rural. Remote Health 2022, 22, 6585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, J.B.; Alfageme, I.; Miravitlles, M.; de Lucas, P.; Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; García-Río, F.; Casanova, C.; Rodríguez González-Moro, J.M.; Cosío, B.G.; Sánchez, G.; et al. Prevalence and Determinants of COPD in Spain: EPISCAN II. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2021, 57, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sönnerfors, P.; Skavberg Roaldsen, K.; Ståhle, A.; Wadell, K.; Halvarsson, A. Access to, use, knowledge, and preferences for information technology and technical equipment among people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Sweden. A cross-sectional survey study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics. Survey on Household Equipment and Use of Information and Communication Technologies. 2023. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/tich_2023.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- National Institute of Statistics. Trends in Individuals (2006–2021) by Demographic Characteristics, Type of ICT Use, and Time Period. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?tpx=50093 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- National Institute of Statistics. Survey on Household Equipment and Use of Information and Communication Technologies. 2022. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/tich_2022.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- National Institute of Statistics. Survey on Household Equipment and Use of Information and Communication Technologies. 2021. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/tich_2021.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Mitsiki, E.; Bania, E.; Varounis, C.; Gourgoulianis, K.I.; Alexopoulos, E.C. Characteristics of prevalent and new COPD cases in Greece: The GOLDEN study. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2015, 10, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koblizek, V.; Milenkovic, B.; Barczyk, A.; Tkacova, R.; Somfay, A.; Zykov, K.; Tudoric, N.; Kostov, K.; Zbozinkova, Z.; Svancara, J.; et al. Phenotypes of COPD patients with a smoking history in Central and Eastern Europe: The POPE Study. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1601446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Abajo Larriba, A.B.; Méndez Rodríguez, E.; González Gallego, J.; Capón Álvarez, J.; Díaz Rodríguez, Á.; Peleteiro Cobo, B. Estimating the percentage of patients with COPD trained in the consultation for the management of inhalers. ADEPOCLE study [Estimación del porcentaje de pacientes con EPOC adiestrados en consulta para el manejo de inhaladores. Estudio ADEPOCLE]. Nutr. Hosp. 2016, 33, 1405–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Meng, W.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Xiong, R.; Wang, J.; Zhao, R.; Zeng, H.; Chen, Y. Errors and Adherence to Inhaled Medications in Chinese Adults with COPD. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2024, 39, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ierodiakonou, D.; Sifaki-Pistolla, D.; Kampouraki, M.; Poulorinakis, I.; Papadokostakis, P.; Gialamas, I.; Atanasio, P.; Bempi, V.; Lampraki, I.; Tsiligianni, J. Adherence to inhalers and comorbidities in COPD patients. A cross-sectional primary care study from Greece. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes de Oca, M.; Menezes, A.; Wehrmeister, F.C.; Lopez Varela, M.V.; Casas, A.; Ugalde, L.; Ramirez-Venegas, A.; Mendoza, L.; López, A.; Surmont, F.; et al. Adherence to inhaled therapies of COPD patients from seven Latin American countries: The LASSYC study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Association between illness perception and adherence to inhaler therapy in elderly Chinese patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2024, 21, 14799731241286837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, B.; Walpola, R.; Mey, A.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S.; Khan, S. Barriers and Strategies for Improving Medication Adherence Among People Living With COPD: A Systematic Review. Respir. Care 2020, 65, 1738–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Individuals—Internet Activities. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/bookmark/a4e0a8bf-ff90-4dd4-920d-e6dce08a0ae0?lang=en (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Eurostat. Individuals Using the Internet for Participating in Social Networks. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tin00127/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Álvarez-Galvez, J.; Salinas-Pérez, J.A.; Montagni, I.; Carulla, L.S. The persistence of digital divides in the use of health information: A comparative study in 28 European countries. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Pang, Y.; Liu, L.S. Online Health Information Seeking Behavior: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llubes-Arrià, L.; Briones-Vozmediano, E.; Mateos, J.T.; Sol-Cullere, J.; Gea-Sánchez, M.; Rubinat-Arnaldo, E. Gender differences in self-management activation among patients with multiple chronic diseases: A qualitative study. Arch. Public Health 2025, 83, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.C.; Liang, L.L.; Huang, M.H.; Huang, C.Y. A comparative study of positive and negative electronic word-of-mouth on the SERVQUAL scale during the COVID-19 epidemic—Taking a regional teaching hospital in Taiwan as an example. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widmer, R.J.; Maurer, M.J.; Nayar, V.R.; Aase, L.A.; Wald, J.T.; Kotsenas, A.L.; Timimi, F.K.; Harper, C.M.; Pruthi, S. Online Physician Reviews Do Not Reflect Patient Satisfaction Survey Responses. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Textual Level | Conceptual Level |

|---|---|

| 1. Preparation of primary data: Transformation to rich text, to facilitate the exchange of documents between different computing platforms. 2. Reading and rereading: Allowed for a global understanding of the transcribed testimony and the fundamental ideas expressed, and familiarization with the language used by the participants. 3. Segmentation of the text into quotes: Text fragments (quotes) relevant to the research objective were identified. 4. Initial coding: A code was applied to each selected text or video quote. Comments were added to the codes to clarify their meaning. The dictionary of the Royal Spanish Language Academy was used in case of doubts about terminology. 5. Focused coding: Review of codes to correct errors, recode, or merge multiple codes with the same meaning. This was carried out (1) in parallel with the first round of coding, when new codes emerged, and previous codes had to be revised; and (2) upon completion. 6. Families: Classification and ordering of codes according to common elements. | 7. Networks: Visual diagrams based on families made up of nodes (codes considered categories with specific meaning due to their position and relationships within the network) and relationships between nodes (links: “is associated with”, “contradicts”, “is a property of”, “is part of”, “is a cause of”, “is a”). Characteristics of the networks: Degree (number of links from each node) and Order (number of nodes in the network). Network analysis: high-degree nodes (higher-level explanatory codes): higher Density (number of quotes referred to) and Foundation (number of relationships with other codes). These nodes were considered central categories of the network. Meta-network analysis: simultaneous analysis of the main nodes of each network. 8. Provisional and Final model. |

| Doubts | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| About its effect | Uncertainty about possible improvement (P29: For my COPD treatment I was prescribed inhalers, Foster Nexthaler and Eklira Genuair, will I get better?) Confusion between lack of effect and worsening of disease (P22: I take it, but I honestly think I was better when I was taking Spiriva and Onbrez. I feel like I’m choking, I don’t know if it’s because I’m worse or because it’s not doing me any good) |

| About side effects | (P20: Good evening group, a question, do inhalers give you fungus? I have a fungus in my mouth and my entire throat) |

| About usage time | (P29: For how long is it advisable to take Enurev to improve COPD?) |

| About usage guidelines | (P29: I have COPD and use Atrovent. Spiriva. Onbrez. Is it necessary to nebulize with Atrovent every day? Can I use Spiriva and Onbreze every day? How long should I leave between one inhaler and the other?) |

| On incompatibilities between inhalers | (P29: I have been admitted for an exacerbation of COPD with emphysema. When I was discharged, as a continuing treatment, they prescribed me Ultibro, which I was already taking, a single inhalation in the morning, and Alvesco, one in the morning and one at night. Are the two compatible?) |

| On the use of rescue treatment and its appropriateness | (P29: I am a 42-year-old woman with moderate COPD but still without symptoms. I play sports (basketball, gym) and since I am so young and have moderate COPD, they told me that I could be a patient with freefalling FEV…I have only been prescribed Ventolin as a rescue treatment. What do you think about treatment and being a “free falling” patient”?) |

| On treatment in exacerbations | (P29: I just dosed myself 3 h ago with 1 ventolin and 2 atrovent inhalers, and I have nebulized with physiological saline solution but my breathing difficulty continues. I suffer from COPD and have just been diagnosed with acute bronchitis. Will taking prednisone help me? What should I do?) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roldán-Tovar, L.; Muñoz-Cobos, F.; Leiva-Fernández, F. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: An Analysis of Online Patient Testimony on Treatment Adherence. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7324. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207324

Roldán-Tovar L, Muñoz-Cobos F, Leiva-Fernández F. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: An Analysis of Online Patient Testimony on Treatment Adherence. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7324. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207324

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoldán-Tovar, Laura, Francisca Muñoz-Cobos, and Francisca Leiva-Fernández. 2025. "Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: An Analysis of Online Patient Testimony on Treatment Adherence" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7324. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207324

APA StyleRoldán-Tovar, L., Muñoz-Cobos, F., & Leiva-Fernández, F. (2025). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: An Analysis of Online Patient Testimony on Treatment Adherence. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7324. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207324