Analysis of Early Post-Radiation Surgical Management of Metastatic Spinal Tumors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Variables

2.3. Multivariate Logistic Analysis and Subgroup Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics Factors and Tumor Grading

3.2. Operative Factors

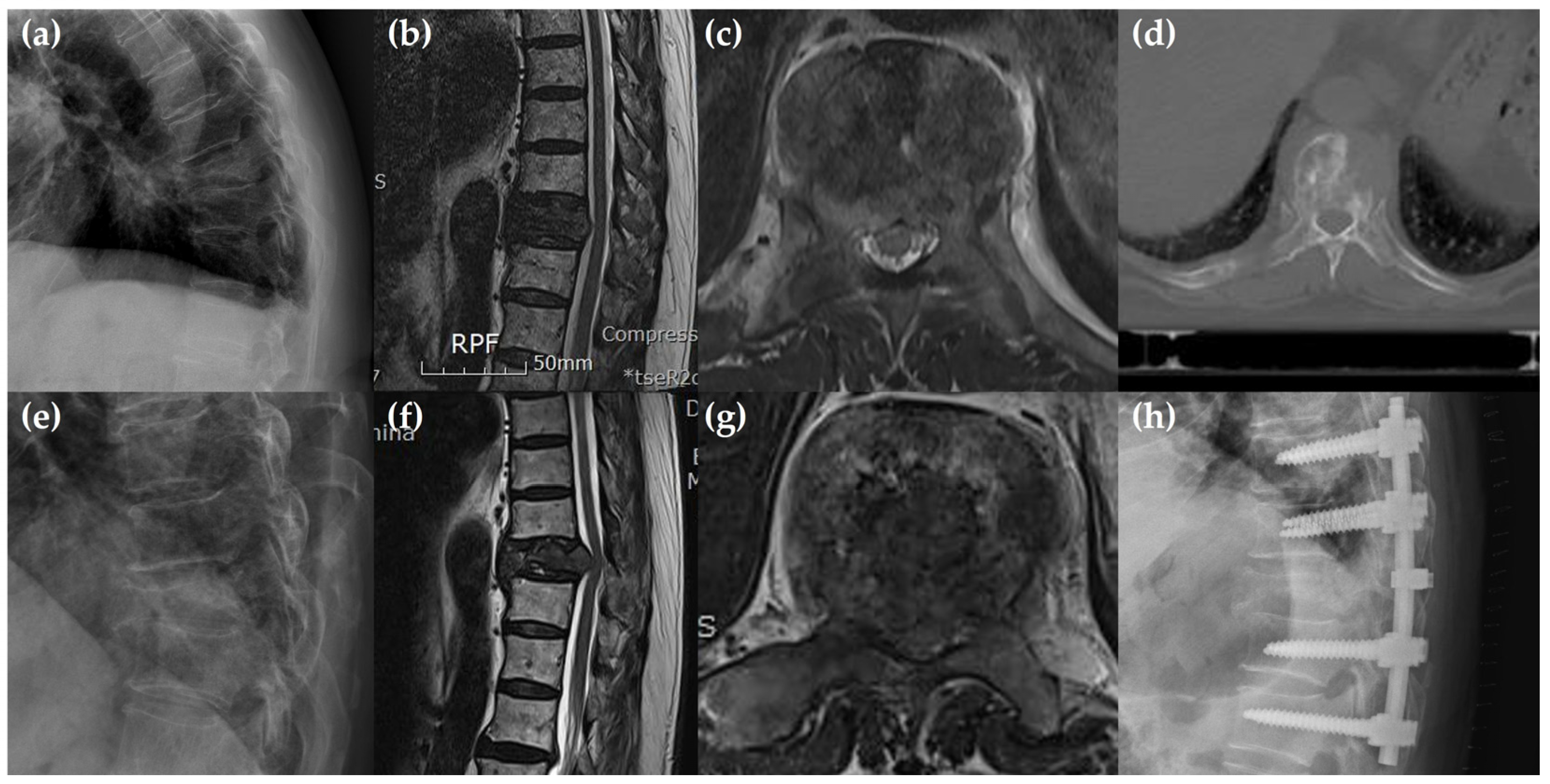

3.3. Preoperative Radiological Findings

3.4. Clinical Findings and Postoperative Findings

3.5. Multivariate Logistic Analysis and Subgroup Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Hong, S.H.; Chang, B.S.; Kim, H.M.; Kang, D.-H.; Chang, S.Y. An Updated Review on the Treatment Strategy for Spinal Metastasis from the Spine Surgeon’s Perspective. Asian Spine J. 2022, 16, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murotani, K.; Fujibayashi, S.; Otsuki, B.; Shimizu, T.; Sono, T.; Onishi, E.; Kimura, H.; Tamaki, Y.; Tsubouchi, N.; Ota, M.; et al. Prognostic Factors after Surgical Treatment for Spinal Metastases. Asian Spine J. 2024, 18, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laufer, I.; Sciubba, D.M.; Madera, M.; Bydon, A.; Witham, T.J.; Gokaslan, Z.L.; Wolinsky, J.-P. Surgical management of metastatic spinal tumors. Cancer Control 2012, 19, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santipas, B.; Veerakanjana, K.; Ittichaiwong, P.; Chavalparit, P.; Wilartratsami, S.; Luksanapruksa, P. Development and internal validation of machine-learning models for predicting survival in patients who underwent surgery for spinal metastases. Asian Spine J. 2024, 18, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.; Kim, J.; Chung, C.K.; Lee, N.-R.; Park, E.; Chang, U.-K.; Sohn, M.J.; Kim, S.H. Nationwide epidemiology and healthcare utilization of spine tumor patients in the adult Korean population, 2009–2012. Neurooncol Pract 2015, 2, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzilai, O.; Fisher, C.G.; Bilsky, M.H. State of the art treatment of spinal metastatic disease. Neurosurgery 2018, 82, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rades, D.; Abrahm, J.L. The role of radiotherapy for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 7, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetty, I.J.; Martel, M.K.; Jaffray, D.A.; Benedict, S.H.; Hahn, S.M.; Berbeco, R.; Deye, J.; Jeraj, R.; Kavanagh, B.; Krishnan, S.; et al. Technology for Innovation in Radiation Oncology. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2015, 93, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganau, M.; Foroni, R.I.; Gerosa, M.; Ricciardi, G.K.; Longhi, M.; Nicolato, A. Radiosurgical options in neuro-oncology: A review on current tenets and future opportunities. Part II: Adjuvant radiobiological tools. Tumori 2015, 101, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C.H.; Hills, J.M.; Anderson, P.A.; Annaswamy, T.M.; Cassidy, R.C.; Craig, C.M.; DeMicco, R.C.; Easa, J.E.; Kreiner, D.S.; Mazanec, D.J.; et al. Appropriate Use Criteria for Neoplastic Compression Fractures. Spine J. 2025, in press. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.C.; Nosyk, B.; Fisher, C.G.; Dvorak, M.; Patchell, R.A.; Regine, W.F.; Loblaw, A.; Bansback, N.; Guh, D.; Sun, H.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of surgery plus radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006, 66, 1212–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Xiao, S.; Tong, X.; Xu, S.; Lin, X. Comparison of the Therapeutic Efficacy of Surgery with or without Adjuvant Radiotherapy versus Radiotherapy Alone for Metastatic Spinal Cord Compression: A Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2015, 83, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothrock, R.J.; Barzilai, O.; Reiner, A.S.; Lis, E.; Schmitt, A.M.; Higginson, D.S.; Yamada, Y.; Bilsky, M.H.; Laufer, I. Survival Trends After Surgery for Spinal Metastatic Tumors: 20-Year Cancer Center Experience. Neurosurgery 2021, 88, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanphaisarn, A.; Patumanond, J.; Settakorn, J.; Chaiyawat, P.; Klangjorhor, J.; Pruksakorn, D. Prevalence and survival patterns of patients with bone metastasis from common cancers in Thailand. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 17, 4335–4340. [Google Scholar]

- Bilsky, M.H.; Laufer, I.; Fourney, D.R.; Groff, M.; Schmidt, M.H.; Varga, P.P.; Vrionis, F.D.; Yamada, Y.; Gerszten, P.C.; Kuklo, T.R. Reliability analysis of the epidural spinal cord compression scale. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2010, 13, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteeg, A.L.; Verlaan, J.; Sahgal, A.; Mendel, E.; Quraishi, N.A.; Fourney, D.R.; Fisher, C.G. The Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score: Impact on Oncologic Decision-Making. Spine 2016, 15, S231–S237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schag, C.C.; Heinrich, R.L.; Ganz, P.A. Karnofsky performance status revisited: Reliability, validity and guidelines. J. Clin. Oncol. 1984, 2, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniwaki, H.; Dohzono, S.; Sasaoka, R.; Takamatsu, K.; Hoshino, M.; Nakamura, H. Computed tomography Hounsfield unit values as a treatment response indicator for spinal metastatic lesions in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: A retrospective study in Japan. Asian Spine J. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhou, Q.; Da, L.; Zhang, G. Efficacy and safety of en-bloc resection versus debulking for spinal tumor: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 22, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, I.; Kennedy, J.; Morris, S.; Crockard, A.; Choi, D. Surgery and Radiotherapy for Symptomatic Spinal Metastases Is More Cost Effective Than Radiotherapy Alone: A Cost Utility Analysis in a U.K Spine Center. World Neurosurg. 2018, 109, e389–e397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.C.; Tang, C.; Deegan, B.J.; Allen, P.K.; Jonasch, E.; Amini, B.; Wang, X.A.; Li, J.; Tatsui, C.E.; Rhines, L.D.; et al. The use of spine stereotactic radiosurgery for oligometastatic disease. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2016, 25, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahgal, A.; Whyne, C.M.; Ma, L.; Larson, D.A.; Fehlings, M.G. Vertebral compression fracture after stereotactic body radiotherapy for spinal metastases. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, e310–e320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahgal, A.; Atenafu, E.G.; Chao, S.; Al-Omair, A.; Boehling, N.; Balagamwala, E.H.; Cunha, M.; Thibault, I.; Angelov, L.; Brown, P.; et al. Vertebral compression fracture after spine stereotactic body radiotherapy: A multi-institutional analysis with a focus on radiation dose and the spinal instability neoplastic score. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 3426–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce-Fappiano, D.; Elibe, E.; Schultz, L.; Ryu, S.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Chetty, I.; Siddiqui, F.; Movsas, B.; Rock, J.; Lee, I. Analysis of the factors contributing to vertebral compression fractures after spine stretotactic radiosurgery. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017, 97, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafage, R.; Steinberger, J.; Pesenti, S.; Assi, A.; Elysee, J.C.; Iyer, S.; Lafage, V.; Han, J.; Frank, J.; Lawrence, G. Understanding Thoracic Morphology, Shape, and Proportionality. Spine 2020, 45, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, M.W.; Hornicek, F.J.; Schwab, J.H. Spinal cord blood supply and its surgical implications. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2015, 23, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommisse, G.F. The blood supply of the spinal cord. A critical vascular zone in spinal surgery. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1974, 56, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falavigna, A.; Righesso Neto, O.; Ioppi, A.E.E.; Grasselli, J. Metastatic tumor of thoracic and lumbar spine: Prospective study comparing the surgery and radiotherapy vs external immobilization with radiotherapy. Arq. Neurosiquiatr. 2007, 65, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Park, J.W.; Park, J.H.; Lee, C.S.; Lee, D.H.; Hwang, C.J.; Cho, J.H.; Yang, J. Factors affecting the prognosis of recovery of motor power and ambulatory function after surgery for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression. Neurosurg. Focus. 2022, 53, E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, I.; Rubin, D.G.; Lis, E.; Cox, B.W.; Stubblefield, M.D.; Yamada, Y.; Bilsky, M.H. The NOMS framework: Approach to the treatment of spinal metastatic tumors. Oncologist 2013, 18, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brande, R.V.d; Cornips, E.M.; Peeters, M.; Ost, P.; Billiet, C.; Van de Kelft, E. Epidemiology of spinal metastases, metastatic epidural spinal cord compression and pathologic vertebral compression fractures in patients with solid tumors: A systematic review. J. Bone Oncol. 2022, 35, 100446. [Google Scholar]

- Patchell, R.A.; Tibbs, P.A.; Regine, W.F.; Payne, R.; Saris, S.; Kryscio, R.J.; Young, B.; Mohiuddin, M. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: A randomized trial. Lancet 2005, 366, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Patel, R.S.; Wang, S.S.Y.; Tan, J.Y.H.; Singla, A.; Chen, Z.; Ravikumar, N.; Tan, A.; Kumar, N.; Hey, D.H.W.; et al. Factors influencing extended hospital stay in patients undergoing metastatic spine tumour surgery and its impact on survival. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 56, 120–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, R.D.G.; Goodwin, C.R.; Jain, A.; Abu-Bonsrah, N.; Fisher, C.G.; Bettegowda, C.; Sciubba, D.M. Development of a Metastatic Spinal Tumor Frailty Index (MSTFI) Using a Nationwide Database and Its Association with Inpatient Morbidity, Mortality, and Leng of Stay After Spine Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2016, 95, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendfeldt, G.A.; Chanbour, H.; Chen, J.W.; Gangavarapu, L.S.; LaBarge, M.E.; Ahmed, M.; Zuckerman, S.L.; Stephens, B.F.; Abtahi, A.M.; Luo, L.Y.; et al. Does Low-Grade Versus High-Grade Bilsky Score Influence Local Recurrence and Overall Survival in Metastatic Spinal Tumor Surgery? Neurosurgery 2023, 93, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group E | Group L | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 47 | n = 34 | ||

| Demographic factor | |||

| -Age | 57.2 ± 11.5 | 57.6 ± 8.9 | 0.856 |

| -Sex | 0.512 | ||

| -Male | 31 (65.9) | 20 (58.8) | |

| -Female | 16 (34.1) | 14 (41.2) | |

| -Body mass index | 23.5 ± 6.2 | 23.8 ± 5.9 | 0.802 |

| -Smoking | 7 (19.3) | 7 (13.7) | 0.532 |

| -Operative timing from radiotherapy | 2.1 ± 3.1 | 14.3 ± 7.3 | <0.001 * |

| -Cause of the operation | |||

| -Neurological deficits | 30 (63.8) | 23 (67.6) | 0.721 |

| -Mechanical pain | 39 (83.0) | 29 (85.3) | 0.779 |

| -Preoperative embolization | 23 (48.9) | 14 (41.2) | 0.489 |

| -Hypertension | 16 (35.5) | 15 (41.4) | 0.357 |

| -Diabetes mellitus | 7 (14.9) | 9 (26.5) | 0.363 |

| -Liver disease | 11 (23.4) | 6 (17.6) | 0.530 |

| -Pulmonary disease | 5 (10.6) | 6 (17.6) | 0.364 |

| Primary cancer | 0.261 | ||

| -Lung | 12 (25.5) | 6 (17.6) | |

| -Breast | 4 (8.5) | 4 (11.7) | |

| -Prostate | 3 (6.4) | 2 (5.9) | |

| -Kidney | 2 (4.2) | 8 (23.5) | |

| -Thyroid | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| -Hepatic | 11 (23.4) | 9 (26.5) | |

| -Stomach, colon | 5 (10.6) | 2 (5.9) | |

| -Sarcoma | 2 (4.2) | 0 | |

| -Others | 7 (14.9) | 3 (8.8) | |

| Location | 0.025 * | ||

| -Junctional region (cervico-occipital, cervicothoracic, thoracolumbar) | 15 (31.9) | 9 (26.8) | 0.596 |

| -Mobile (cervical, lumbar) | 6 (12.8) | 13 (38.2) | 0.008 * |

| -Semirigid (thoracic) | 26 (55.3) | 12 (35.2) | 0.075 |

| -Rigid (sacrum) | 0 | 0 | <0.001 * |

| Radiosensitivity | 0.872 | ||

| -Radiosensitive | 9 (19.1) | 7 (20.6) | |

| -Radioresistant | 38 (80.9) | 27 (79.4) | |

| Level of metastasis in spine | 0.344 | ||

| -One level | 29 (61.7) | 26 (76.5) | |

| -Two levels | 6 (12.8) | 2 (5.9) | |

| -Above three levels | 12 (25.5) | 6 (17.6) | |

| Tumor grading | |||

| -Bilsky grade 1 | 2 (4.2) | 4 (11.7) | 0.203 |

| Grade 2 | 17 (36.2) | 11 (32.4) | 0.721 |

| Grade 3 | 28 (59.6) | 19 (55.9) | 0.740 |

| -SINS | 11.1 ± 3.2 | 10.0 ± 2.8 | 0.107 |

| -Karnofsky performance scale | 58.7 ± 10.7 | 58.5 ± 17.7 | 0.951 |

| Group E | Group L | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 47 | n = 34 | ||

| Operative factors | |||

| -Operation time | 184.5 ± 85.3 | 193.0 ± 74.9 | 0.635 |

| -Estimated blood loss | 480.0 ± 575.5 | 627.7 ± 629.4 | 0.338 |

| -Transfusion | 20 (42.6) | 17 (50.0) | 0.429 |

| -Transfusion amount | 1307.2 ± 1637.7 | 972.6 ± 672.6 | 0.388 |

| -Decompression methods | 0.166 | ||

| -Posterior decompression + corpectomy | 13 (27.7) | 5 (14.7) | |

| -Posterior decompression | 34 (72.3) | 29 (85.3) | |

| -Fixation levels | 0.757 | ||

| -Above and below two levels | 45 (95.7) | 33 (97.1) | |

| -Above and below three levels | 2 (4.3) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Preoperative radiological findings | |||

| -Cord compression | 45 (89.4) | 30 (67.6) | 0.203 |

| -Pathologic fracture | 42 (89.4) | 20 (58.8) | 0.001 * |

| -Vertebral body collapse | 0.308 | ||

| -50% < | 28 (59.6) | 24 (70.6) | |

| -50% > | 19 (40.4) | 10 (29.4) | |

| -Posterolateral involvement | 42 (89.4) | 31 (91.2) | 0.787 |

| -Anterior dura compression | 45 (93.6) | 29 (79.4) | 0.099 |

| -Tumor characters | |||

| -Osteolytic lesion | 37 (78.7) | 21 (61.8) | 0.095 |

| -Osteoblastic lesion | 2 (4.3) | 5 (14.7) | 0.099 |

| -Mixed lesion | 8 (17.0) | 8 (23.5) | 0.468 |

| Group E | Group L | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 47 | n = 34 | ||

| Clinical findings | |||

| -Preoperative motor grade | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 0.495 |

| -Postoperative motor grade -Preoperative ambulation | 4.3 ± 0.9 | 4.0 ± 1.3 | 0.234 |

| 31 (66.0) | 25 (73.5) | 0.467 | |

| -Postoperative ambulation | 34 (72.3) | 26 (76.5) | 0.675 |

| -Hospital stay | 26.3 ± 26.2 | 16.7 ± 10.5 | 0.048 * |

| -Final follow up | 8.7 ± 9.8 | 14.4 ± 12.6 | 0.034 * |

| Postoperative complication | |||

| -Local recurrence | 10 (21.3) | 9 (26.5) | 0.586 |

| -Hematoma | 2 (4.3) | 1 (2.9) | 1.000 |

| -Dural tear, nerve injury | 2 (4.3) | 0 | 0.509 |

| -Pleural injury | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.9) | 1.000 |

| -Infection | 2 (4.3) | 1 (2.9) | 1.000 |

| -Wound problem | 2 (4.3) | 2 (5.8) | 1.000 |

| B | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semirigid lesion | 1.103 | 4.282 | 1.060–8.570 | 0.039 |

| Pathologic fracture | 2.103 | 10.524 | 2.299–29.189 | 0.001 * |

| Osteolytic lesion | 1.023 | 3.320 | 0.926–8.363 | 0.068 |

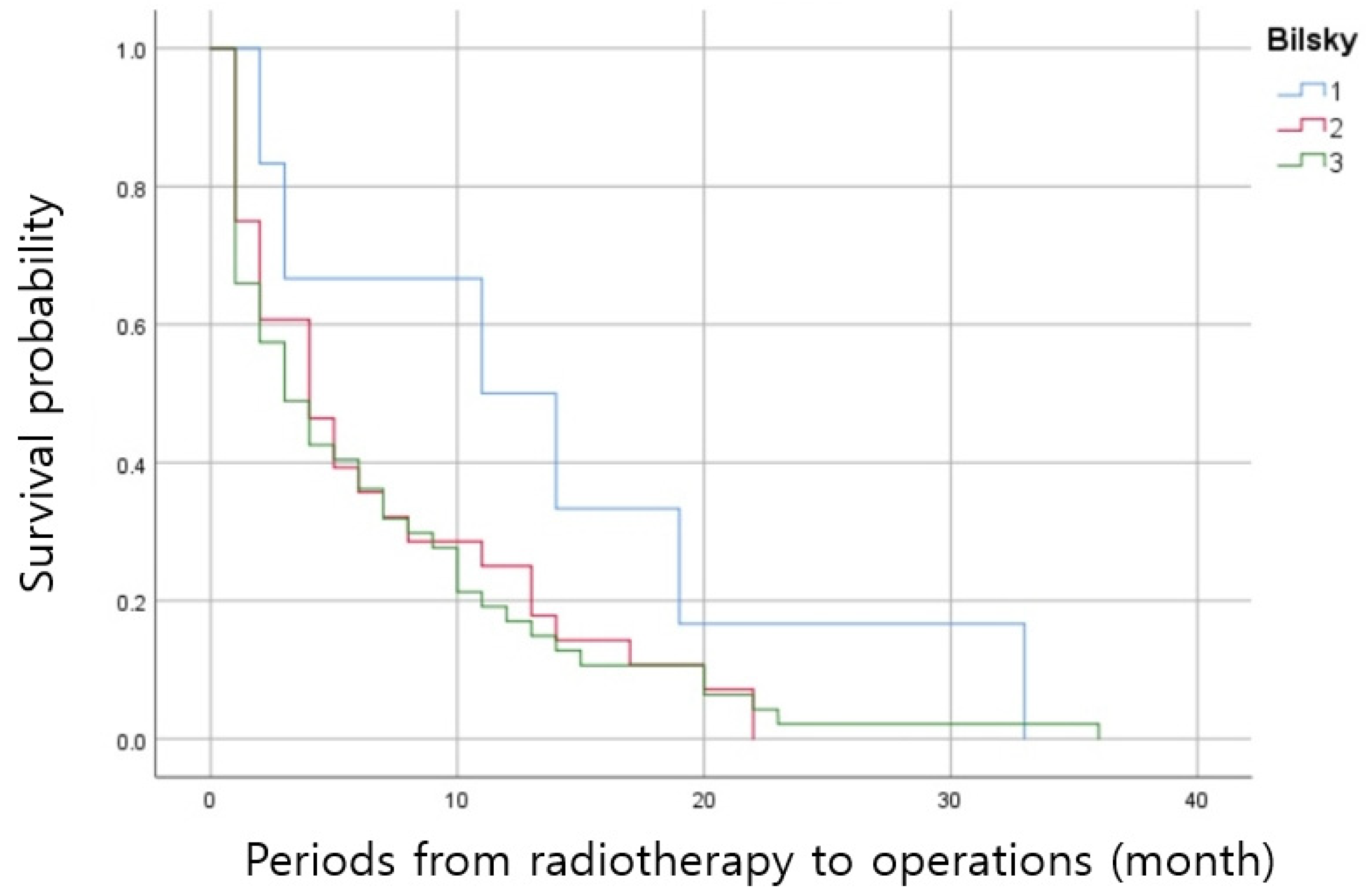

| N | Periods from Radiotherapy to Surgery (mo) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| -Bilsky grade | |||

| -Bilsky 1 | 6 | 13.6 ± 11.4 | 0.049 * |

| -Bilsky 2 | 28 | 6.9 ± 6.8 | |

| -Bilsky 1 | 6 | 13.6 ± 11.4 | 0.047 * |

| -Bilsky 3 | 47 | 6.6 ± 7.5 | |

| -Bilsky 2 | 28 | 6.9 ± 6.8 | 0.868 |

| -Bilsky 3 | 47 | 6.6 ± 7.5 | |

| Group E | Group L | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 17 | n = 11 | ||

| Operation from radiotherapy | 2.4 ± 1.5 | 13.9 ± 5.7 | <0.001 * |

| Operation due to pain | 16 (94.1) | 10 (90.9) | 0.747 |

| Operation due to neurologic deficit | 8 (47.1) | 8 (72.7) | 0.180 |

| Semirigid lesion | 12 (70.6) | 6 (54.5) | 0.387 |

| Pathologic fracture | 16 (94.1) | 6 (54.5) | 0.013 * |

| Cord compression | 17 (100.0) | 11 (100.0) | 1.000 |

| Vertebral body collapse | 4 (23.5) | 2 (18.2) | 0.736 |

| Anterior dural compression | 16 (94.1) | 8 (72.7) | 0.114 |

| Osteolytic lesion | 14 (82.3) | 6 (54.5) | 0.112 |

| Osteoblastic lesion | 1 (5.9) | 1 (9.1) | 0.747 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seok, S.Y.; Cho, J.H.; Lee, H.R.; Park, J.W.; Park, J.H.; Lee, D.-H.; Hwang, C.J.; Park, S. Analysis of Early Post-Radiation Surgical Management of Metastatic Spinal Tumors. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14031032

Seok SY, Cho JH, Lee HR, Park JW, Park JH, Lee D-H, Hwang CJ, Park S. Analysis of Early Post-Radiation Surgical Management of Metastatic Spinal Tumors. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(3):1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14031032

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeok, Sang Yun, Jae Hwan Cho, Hyung Rae Lee, Jae Woo Park, Jin Hoon Park, Dong-Ho Lee, Chang Ju Hwang, and Sehan Park. 2025. "Analysis of Early Post-Radiation Surgical Management of Metastatic Spinal Tumors" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 3: 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14031032

APA StyleSeok, S. Y., Cho, J. H., Lee, H. R., Park, J. W., Park, J. H., Lee, D.-H., Hwang, C. J., & Park, S. (2025). Analysis of Early Post-Radiation Surgical Management of Metastatic Spinal Tumors. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(3), 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14031032