Intraoperative Surgical Navigation Is as Effective as Conventional Surgery for Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fracture Reduction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Process

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Data Collection Process

2.5. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Certainty of Evidence

2.7. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

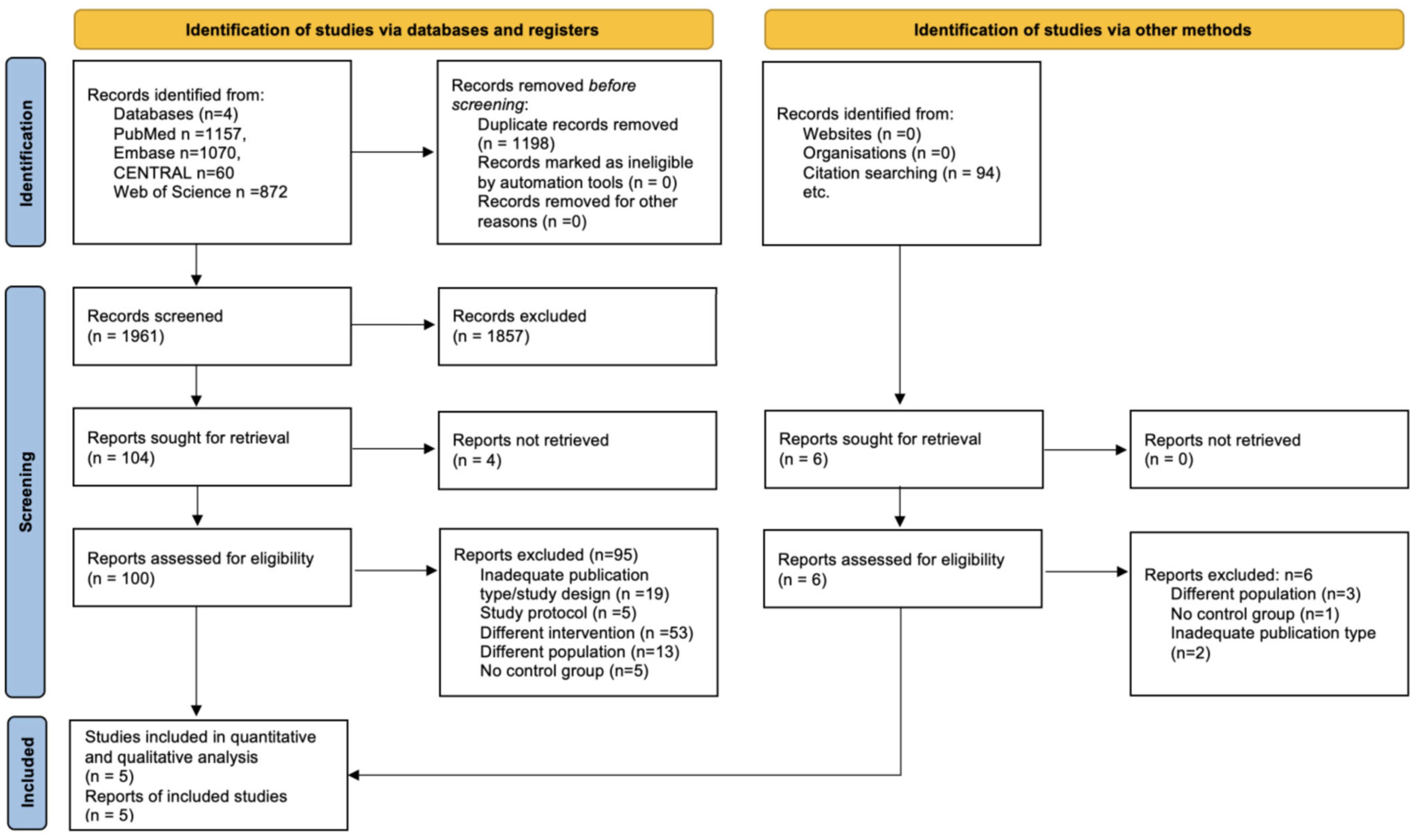

3.1. Search and Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.2.1. Description of Excluded Studies

3.2.2. Description of Included Studies

3.2.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.2.4. Certainty of Evidence

3.3. Primary Outcome (Accuracy)

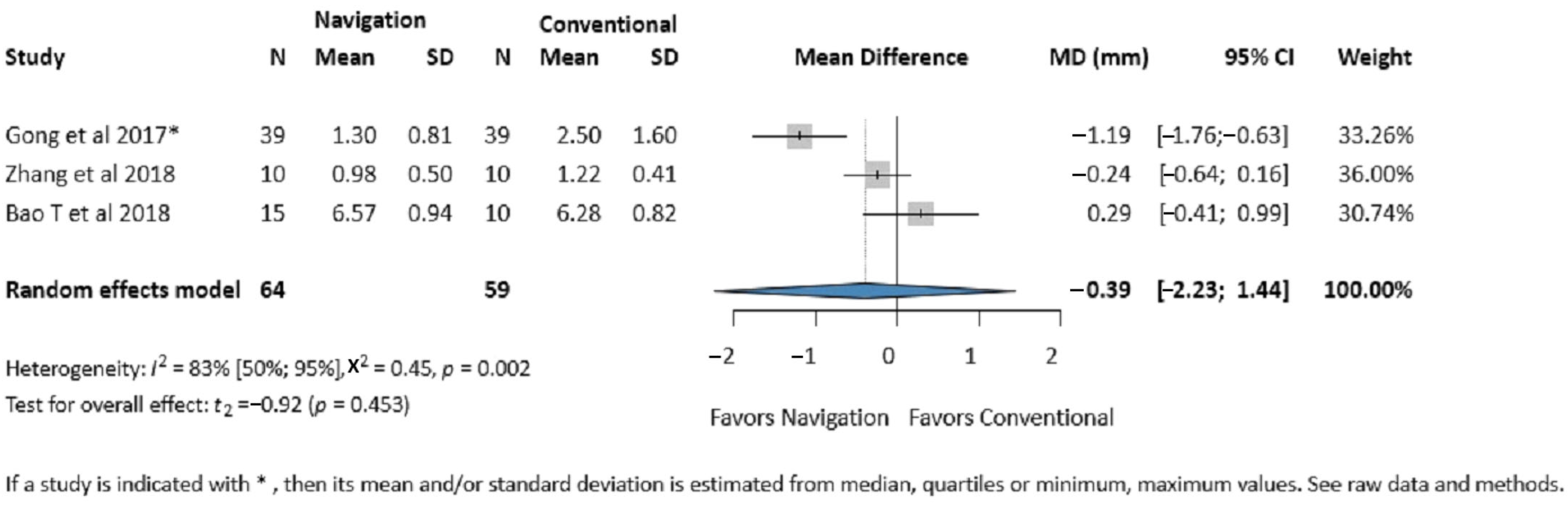

3.3.1. Zygomatic Eminence Accuracy

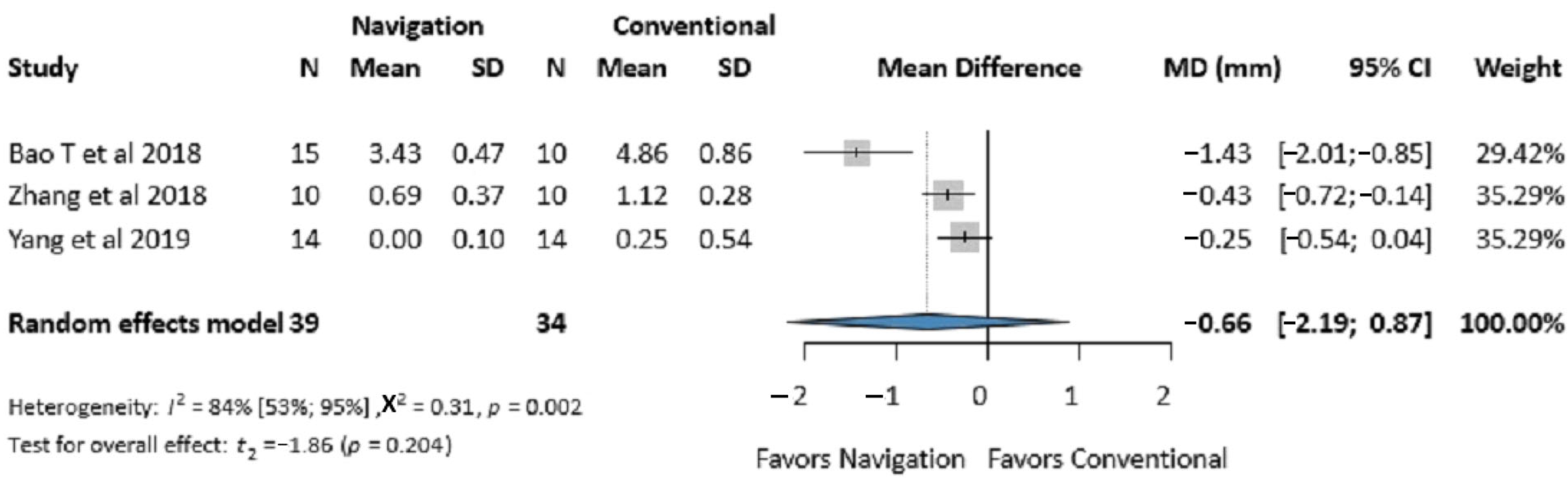

3.3.2. Infraorbital Rim Accuracy

3.3.3. Average Deviation of the Zygomatic Bone

3.4. Secondary Outcomes

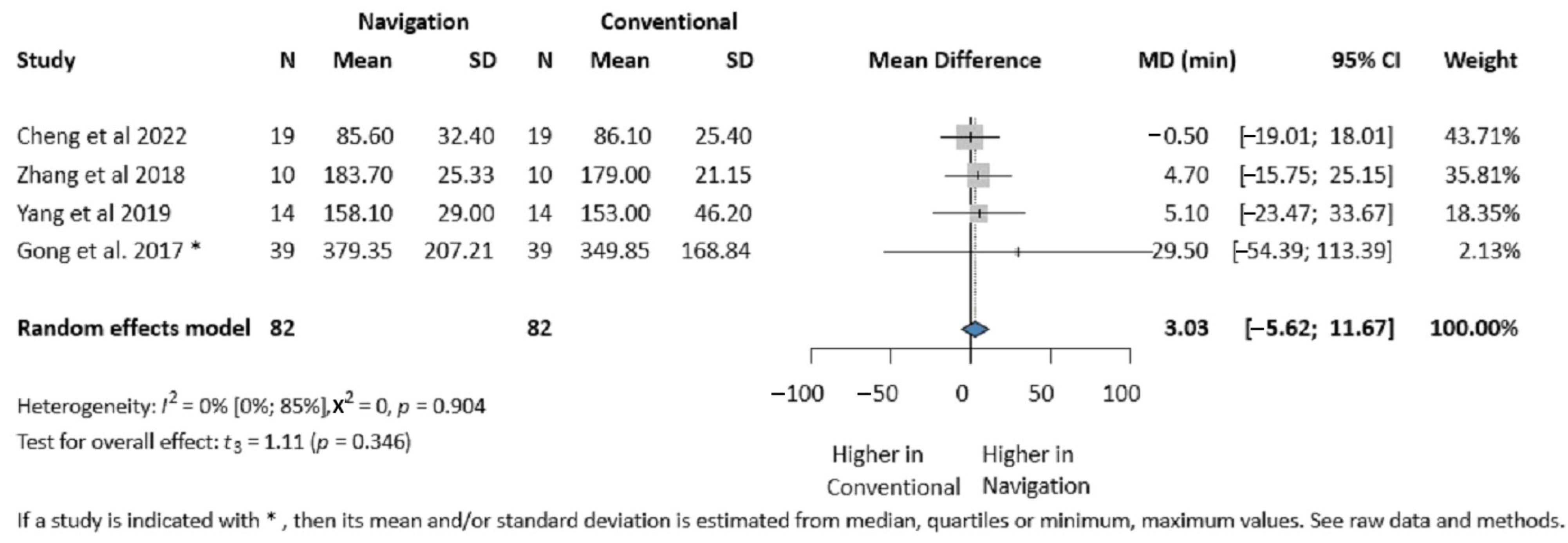

3.4.1. Operative Time

3.4.2. Mouth Opening

3.4.3. Postoperative Stay and Amount of Bleeding

3.4.4. Complications (Cheek Numbness, Screw Loosening, Wound Infection)

3.4.5. Orbital Volume, Diplopia, Enophthalmos

3.4.6. Publication Bias and Heterogeneity

4. Discussion

5. Strengths

6. Limitations

6.1. Implication for Practice

6.2. Implication for Research

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kelley, P.; Hopper, R.; Gruss, J. Evaluation and treatment of zygomatic fractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007, 120 (Suppl. 2), 5S–15S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.; Kim, Y.; Choi, Y. Three-dimensional analysis of facial asymmetry after zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture reduction: A retrospective analysis of 101 East Asian patients. Arch. Craniofac Surg. 2021, 22, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadkari, N.; Bawane, S.; Chopra, R.; Bhate, K.; Kulkarni, D. Comparative evaluation of 2-point vs 3-point fixation in the treatment of zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures—A systematic review. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 1542–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zingg, M.; Laedrach, K.; Chen, J.; Chowdhury, K.; Vuillemin, T.; Sutter, F.; Raveh, J. Classification and Treatment of Zygomatic Fractures. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 1992, 50, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covington, D.S.; Wainwright, D.J.; Teichgraeber, J.F.; Parks, D.H. Changing patterns in the epidemiology and treatment of zygoma fractures: 10-year review. J. Trauma 1994, 37, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogino, A.; Onishi, K.; Maruyama, Y. Intraoperative repositioning assessment using navigation system in zygomatic fracture. J. Craniofac Surg. 2009, 20, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shen, S.; Qian, Y.; Yu, H. Efficacy of surgical navigation in zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures: Randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 51, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korb, W.; Marmulla, R.; Raczkowsky, J.; Mühling, J.; Hassfeld, S. Robots in the operating theatre—Chances and challenges. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 33, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.B. Computer planning and intraoperative navigation in cranio-maxillofacial surgery. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 22, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Wu, J.; Shen, S.G.; Xu, B.; Shi, J.; Zhang, S. Interdisciplinary Surgical Management of Multiple Facial Fractures With Image-Guided Navigation. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73, 1767–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, J.M.; Joy, M.; Goldenberg, A.; Kreindler, D. Andrew Goldenberg, Computer- and Robot-assisted Resection of Thalamic Astrocytomas in Children. Neurosurgery 1991, 29, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich Sure, O.A.; Petermeyer, M.; Becker, R.; Bertalanffy, H. Advanced image-guided skull base surgery. Surg. Neurol. 2000, 53, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.-K.; Cheung, L.-K. Clinical Applications of a Real-time Computer-assisted Navigation System for Dental Implantology. Asian J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2005, 17, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, C.S.; Taylor, H.O.; Sullivan, S.R. Utilization of Intraoperative 3D Navigation for Delayed Reconstruction of Orbitozygomatic Complex Fractures. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2013, 24, e284–e286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, B.; Shi, J.; Yu, H.; Cai, M.; Zhang, W.; et al. An excellent navigation system and experience in craniomaxillofacial navigation surgery: A double-center study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarmehr, I.; Stokbro, K.; Bell, R.B.; Thygesen, T. Surgical Navigation: A Systematic Review of Indications, Treatments, and Outcomes in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 1987–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, L.; Bouchard, S.; Bonapace-Potvin, M.; Bergeron, F. Intraoperative Surgical Navigation Reduces the Surgical Time Required to Treat Acute Major Facial Fractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 144, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demian, N.; Pearl, C.; Woernley, T.C.; Wilson, J.; Seaman, J. Surgical Navigation for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 31, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubron, K.; Van Camp, P.; Jacobs, R.; Politis, C.; Shaheen, E. Accuracy of virtual planning and intraoperative navigation in zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures: A systematic review. J. Stomatol. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 123, e841–e848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, B.; Ma, D. The Role of Intraoperative Navigation in Surgical Treatment of Unilateral Zygomatic Complex Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 81, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Scholten, R.J.; Clarke, M.; Hetherington, J. The Cochrane Collaboration. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59 (Suppl. 1), S147–S149; discussion S195–S196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.H.J.; Higgins, J.P.; Elbers, R.G.; Reeves, B.C.; the development group for ROBINS-I. Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I): Detailed Guidance. 2016. Available online: http://www.riskofbias.info (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Holger Schünemann, J.B.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. Factors determining the quality of evidence. In GRADE Handbook; Grade Working Group: Rome, Italy, 2013; Chapter 5.1. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Luo, D.; Weng, H.; Zeng, X.; Lin, L.; Chu, H.; Tong, T. Optimally estimating the sample standard deviation from the five-number summary. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 11, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Wan, X.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2018, 27, 1785–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ye, L.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Dilxat, D.; Liu, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L. Surgical navigation improves reductions accuracy of unilateral complicated zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lee, M.-C.; Pan, C.-H.; Chen, C.-H.; Chen, C.-T. Application of Computer-Assisted Navigation System in Acute Zygomatic Fractures. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2019, 82 (Suppl. 1), S53–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IntHout, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Borm, G.F. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, G.; Hartung, J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat. Med. 2003, 22, 2693–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veroniki, A.A.; Jackson, D.; Viechtbauer, W.; Bender, R.; Bowden, J.; Knapp, G.; Kuss, O.; Higgins, J.P.; Langan, D.; Salanti, G. Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2016, 7, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, M.; Cuijpers, P.; Furukawa, T.; Ebert, D. Doing Meta-Analysis with R: A Hands-On Guide, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbord, R.M.; Harris, R.J.; Sterne, J.A.C. Updated Tests for Small-study Effects in Meta-analyses. Stata J. 2009, 9, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, G. Meta: General Package for Meta-Analysis. R News 2023, 7, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; He, Y.; An, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, X.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Application of a Computer-Assisted Navigation System (CANS) in the Delayed Treatment of Zygomatic Fractures: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 1450–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T.; Yu, D.; Luo, Q.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhu, H. Quantitative assessment of symmetry recovery in navigation-assisted surgical reduction of zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, J.J.; Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G. Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2021; version 6.2. [Google Scholar]

- Rohit, V.; Prajapati, V.-K.; Shahi, A.-K.; Prakash, O.; Ekram, S. Incidence, etiology and management zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2021, 13, e215. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, A.A.; Zhi, L.; Zu Bing, L.; Xing, W.U.Z. Evaluation of treatment of zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fractures: A retrospective study of 10 years. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2012, 11, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaqani, M.S.; Tavosi, F.; Gholami, M.; Eftekharian, H.R.; Khojastepour, L. Analysis of Facial Symmetry After Zygomatic Bone Fracture Management. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2018, 76, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giran, G.; Paré, A.; Croisé, B.; Koudougou, C.; Mercier, J.M.; Laure, B.; Corre, P.; Bertin, H. Radiographic evaluation of percutaneous transfacial wiring versus open internal fixation for surgical treatment of unstable zygomatic bone fractures. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.G.; Kang, C.-S.; Kim, Y.-H.; Chung, K.-J. A Comparative Analysis of Outcomes After Reduction of Zygomatic Fractures Using the Carroll-Girard T-bar Screw. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2020, 85, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; An, J.-G.; Gong, X.; Feng, Z.-Q.; Guo, C.-B. Zygomatic surface marker-assisted surgical navigation: A new computer-assisted navigation method for accurate treatment of delayed zygomatic fractures. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2013, 71, 2101–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.Y.; Yang, J.-R.; Pek, C.-H.; Liao, H.-T. Application of real-time surgical navigation for zygomatic fracture reduction and fixation. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2022, 75, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.Y.; Yang, J.-R.; Lai, B.-R.; Liao, H.-T. Preliminary outcomes of the surgical navigation system combined with intraoperative three-dimensional C-arm computed tomography for zygomatico-orbital fracture reconstruction. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, C.L.; Shi, Y.-L.; Jia, J.-Q.; Ding, M.-C.; Chang, S.-P.; Lu, J.-B.; Chen, Y.-L.; Tian, L. A retrospective study to compare the treatment outcomes with and without surgical navigation for fracture of the orbital wall. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2021, 24, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Li, Z.; Shi, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, H.; Lin, M.; Shen, G.; Fan, X. Orbitozygomatic fractures with enophthalmos: Analysis of 64 cases treated late. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2012, 70, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Shen, S.G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S. The indication and application of computer-assisted navigation in oral and maxillofacial surgery-Shanghai’s experience based on 104 cases. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2013, 41, 770–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collyer, J. Stereotactic navigation in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Br. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2010, 48, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthappu, M.; Duclos, A.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Orgill, D.; Carty, M.J. Surgical learning curves and operative efficiency: A cross-specialty observational study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, A.N.; Jamison, M.H.; Lewis, W.G. Learning curves in surgical practice. Postgrad. Med. J. 2007, 83, 777–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz, M.R.; Bell, R.B. Modern concepts in computer-assisted craniomaxillofacial reconstruction. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck. Surg. 2011, 19, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.Y.; Ryu, D.W.; Yang, J.D.; Chung, H.Y.; Cho, B.C. Feasibility of 4-point fixation using the preauricular approach in a zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2013, 24, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, G.; Koulechov, K.; Röttger, S.; Bahner, J.; Trantakis, C.; Hofer, M.; Korb, W.; Burgert, O.; Meixensberger, J.; Manzey, D.; et al. Evaluation of a navigation system for ENT with surgical efficiency criteria. Laryngoscope 2006, 116, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spalthoff, S.; Oetzel, F.; Dupke, C.; Zeller, A.-N.; Jehn, P.; Gellrich, N.-C.; Korn, P. Quantitative analysis of soft tissue sagging after lateral midface fractures: A 10-year retrospective study. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 123, e619–e625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, R.E.; Buchman, S.R. Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures. In Operative Plastic Surgery; Evans, G.R.D., Evans, G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; p. 623. [Google Scholar]

| Author, Year | Zhang et al., 2018 [29] | Cheng et al., 2022 [7] | Bao T et al., 2018 [41] | Yang et al., 2019 [30] | Gong et al., 2017 [40] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country (center) | China (single-center) | China (single-center) | China (single-center) | Taiwan (single-center) | China (single-center) |

| Type of study | RCT | RCT | Retrospective | Retrospective | RCT |

| Sample size (navigation) | 10 | 19 | 15 | 14 | 39 |

| Sample size (conventional) | 10 | 19 | 10 | 14 | 39 |

| Type of fracture | Unilateral ZMC fractures of type B with delayed surgery and/or bone defect and type C | Unilateral type B ZMC fractures | Acute unilateral type C fractures | Acute unilateral type B and simple type C fractures | Delayed unilateral ZMC fractures of type B and type C |

| Navigation system | VectorVision 2 navigation system (BrainLAB) | Acc-Navi system (Multi- functional Surgical Navigation System, Shanghai, China) | NR | Kolibri workstation Platform 2.0 (BrainLAB, Feldkirchen, Germany) | VectorVision navigation system (BrainLAB) |

| Examined outcome | Zygomatic eminence accuracy, IO accuracy, average deviation, operative time, maximum mouth opening | Average deviation, operative time, maximum mouth opening, amount of bleeding | Zygomatic eminence accuracy, IO accuracy | IO accuracy, average deviation, operative time, maximum mouth opening, cheek numbness, postoperative stay | Zygomatic eminence accuracy, average deviation, operative time, cheek numbness, postoperative stay, amount of bleeding |

| Cheng, Zhu [7] | MD | MD—95% CI | I2 & 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.1 | 0.68 | [0.20; 1.16] * | 0% [0–90%] | 0.985 |

| −0.5 | 0.67 | [0.16; 1.19] * | 0% [0–90%] | 0.982 |

| 0 | 0.65 | [−0.01; 1.31] | 0% [0–90%] | 0.970 |

| 0.5 | 0.56 | [−0.52; 1.64] | 0% [0–90%] | 0.915 |

| 1 | −0.25 | [−0.90; 0.40] | 0% [0–90%] | 0.544 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bănărescu, M.; Cavalcante, B.G.N.; Ács, M.; Szabó, B.; Harnos, A.; Hegyi, P.; Varga, G.; Costan, V.V.; Gerber, G. Intraoperative Surgical Navigation Is as Effective as Conventional Surgery for Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fracture Reduction. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051589

Bănărescu M, Cavalcante BGN, Ács M, Szabó B, Harnos A, Hegyi P, Varga G, Costan VV, Gerber G. Intraoperative Surgical Navigation Is as Effective as Conventional Surgery for Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fracture Reduction. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(5):1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051589

Chicago/Turabian StyleBănărescu, Mădălina, Bianca Golzio Navarro Cavalcante, Márton Ács, Bence Szabó, Andrea Harnos, Péter Hegyi, Gábor Varga, Victor Vlad Costan, and Gábor Gerber. 2025. "Intraoperative Surgical Navigation Is as Effective as Conventional Surgery for Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fracture Reduction" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 5: 1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051589

APA StyleBănărescu, M., Cavalcante, B. G. N., Ács, M., Szabó, B., Harnos, A., Hegyi, P., Varga, G., Costan, V. V., & Gerber, G. (2025). Intraoperative Surgical Navigation Is as Effective as Conventional Surgery for Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fracture Reduction. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(5), 1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051589