Cognitive Reserve Assessment Scale in Health (CRASH): Its Validity and Reliability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Assessments

2.2.1. Clinical and Sociodemographic Assessment

2.2.2. Functional Assessment

2.2.3. Neuropsychological Assessment

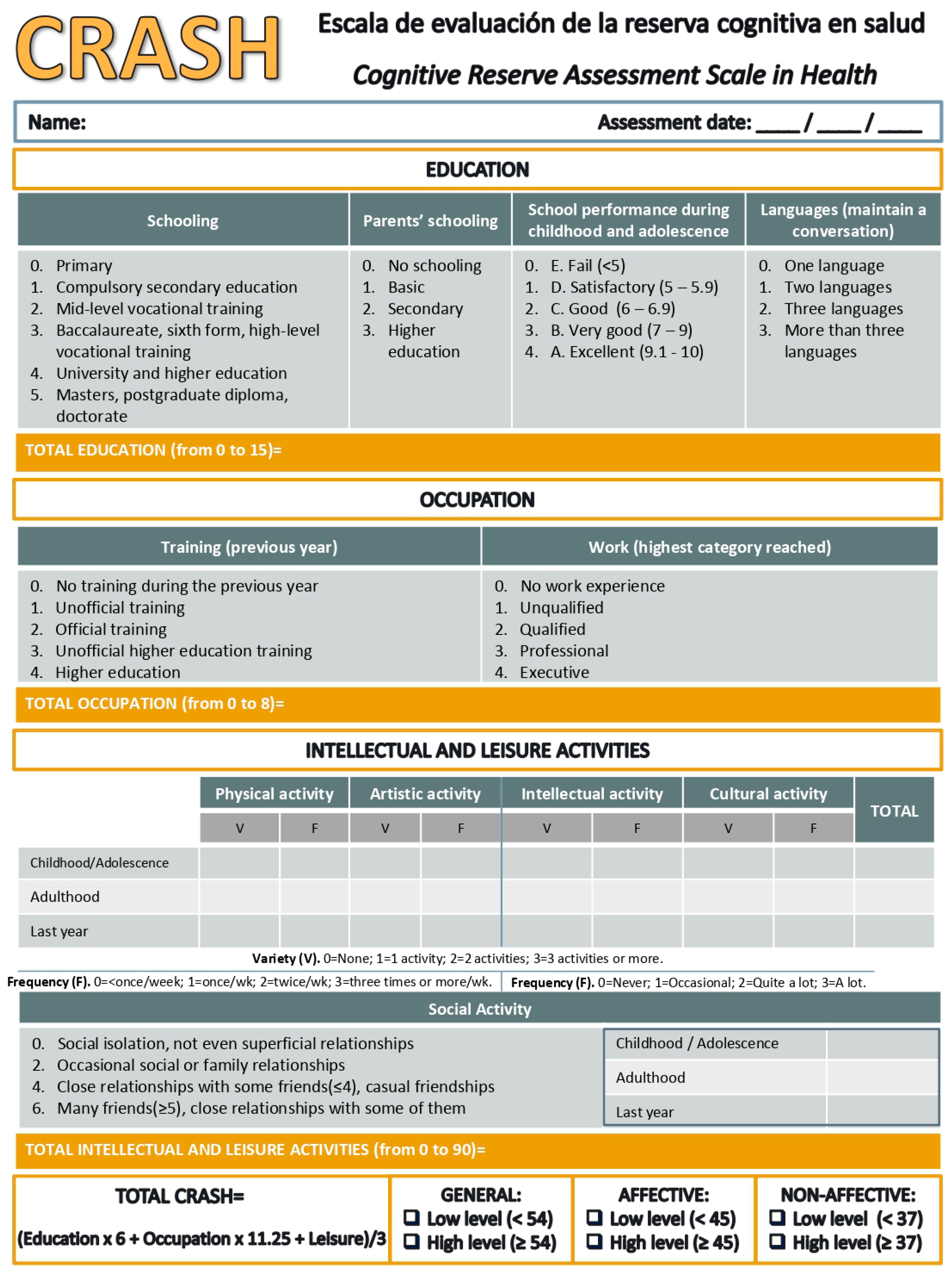

2.2.4. Cognitive Reserve Assessment

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Internal Consistency and Convergent Validity

3.3. Factorial Analysis

3.4. CRASH Score Comparisons Among the Subject Samples and Severity Levels

3.5. Association Between CRASH and CRQ Scales and Clinical, Functionality, and Neuropsychological Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Stern, Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2002, 8, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2006, 20, S69–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.; Salmond, C.; Jones, P.; Sahakian, B. Cognitive reserve in neuropsychiatry. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Serna, E.; Andrés-Perpiñá, S.; Puig, O.; Baeza, I.; Bombin, I.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Arango, C.; Gonzalez-Pinto, A.; Parellada, M.; Mayoral, M.; et al. Cognitive reserve as a predictor of two year neuropsychological performance in early onset first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2013, 143, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontis, D.; Huddy, V.; Reeder, C.; Landau, S.; Wykes, T. Effects of age and cognitive reserve on cognitive remediation therapy outcome in patients with schizophrenia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeson, V.; Sharma, P.; Harrison, M.; Ron, M.; Barnes, T.; Joyce, E. IQ trajectory, cognitive reserve, and clinical outcome following a first episode of psychosis: A 3-year longitudinal study. Schizophr. Bull. 2011, 37, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeson, V.; Harrison, I.; Ron, M.; Barnes, T.; Joyce, E. The effect of cannabis use and cognitive reserve on age at onset and psychosis outcomes in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2012, 38, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forcada, I.; Mur, M.; Mora, E.; Vieta, E.; Bartres-Faz, D.; Portella, M. The influence of cognitive reserve on psychosocial and neuropsychological functioning in bipolar disorder. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaya, C.; Torrent, C.; Caballero, F.F.; Vieta, E.; Bonnin, C.M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; CIBERSAM Functional Remediation Group. Cognitive reserve in bipolar disorder: Relation to cognition, psychosocial functioning and quality of life. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2016, 133, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoretti, S.; Bernardo, M.; Bonnin, C.M.; Bioque, M.; Cabrera, B.; Mezquida, G.; Solé, B.; Vieta, E.; Torrent, C. The impact of cognitive reserve in the outcome of first-episode psychoses: 2-year follow-up study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 1638–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, I.; Sanchez-Moreno, J.; Sole, B.; Jimenez, E.; Torrent, C.; Bonnin, C.M.; Varo, C.; Tabares-Seisdedos, R.; Balanzá-Martínez, V.; Valls, E.; et al. High cognitive reserve in bipolar disorders as a moderator of neurocognitive impairment. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 208, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoretti, S.; Cabrera, B.; Torrent, C.; Mezquida, G.; Lobo, A.; González-Pinto, A.; Parellada, M.; Corripio, I.; Vieta, E.; de la Serna, E.; et al. Cognitive reserve as an outcome predictor: First-episode affective versus non-affective psychosis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018, 138, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, M.J.; Sachdev, P. Assessment of complex mental activity across the lifespan: Development of the Lifetime of Experiences Questionnaire (LEQ). Psychol. Med. 2007, 37, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rami, L.; Valls-Pedret, C.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Caprile, C.; Solé-Padullés, C.; Castellvi, M.; Olives, J.; Bosch, B.; Molinuevo, J.L. Cognitive reserve questionnaire. Scores obtained in a healthy elderly population and in one with Alzheimer’s disease. Rev. Neurol. 2011, 52, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci, M.; Mapelli, D.; Mondini, S. Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire (CRIq): A new instrument for measuring cognitive reserve. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 24, 218–226. [Google Scholar]

- León, I.; García-García, J.; Roldán-Tapia, L. Estimating cognitive reserve in healthy adults using the Cognitive Reserve Scale. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salagre, E.; Arango, C.; Artigas, F.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Bernardo, M.; Castro-Fornieles, J.; Bobes, J.; Desco, M.; Fañanás, L.; González-Pinto, A.; et al. CIBERSAM: Ten years of collaborative translational research in mental disorders. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2019, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingshead, A.; Redlich, F. Social Class and Mental Illness: Community Study; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- First, M.; Gibbon, M.; Spitzer, R.; Williams, J.; Benjamin, L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II); American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- First, M.; Spitzer, R.; Gibbon, M.; Williams, J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Clinician (SCID-I); American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, S.; Fiszbein, A.; Opler, L. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987, 13, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peralta, V.; Cuesta, M. Psychometric properties of the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1994, 53, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom, F.; Vieta, E.; Martínez-Arán, A.; Garcia-Garcia, M.; Reinares, M.; Torrent, C.; Goikolea, J.; Banús, S.; Salamero, M. Spanish version of a scale for the assessment of mania: Validity and reliability of the Young Mania Rating Scale. Med. Clin. (Barc.) 2002, 119, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.; Biggs, J.; Ziegler, V.; Da, M. A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br. J. Psychiatry 1978, 133, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, A.; Chamorro, L.; Luque, A.; Dal-Re, R.; Badia, X.; Baro, E. Validation of the Spanish versions of the Montgomery-Asberg depression and Hamilton anxiety rating scales. Med. Clin. (Barc.) 2002, 118, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S.; Asberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry 1979, 134, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, A.; Sánchez-Moreno, J.; Martínez-Aran, A.; Salamero, M.; Torrent, C.; Reinares, M.; Comes, M.; Colom, F.; Van Riel, W.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.; et al. Validity and reliability of the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) in bipolar disorder. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2007, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (WAIS-III); Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Benedet, M.J.; Alejandre, M.A. Test de Aprendizaje Verbal España-Complutense (TAVEC); TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Conners, C.K. Continuous Performance Test II; Multi-Health Systems: North Tonawanda, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reitan, R.M. Validity of the Trail Making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept. Mot. Skills 1958, 8, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, A.L.; Hamsher, K.S. Multilingual Aphasia Examination; AJA Associates; University of Iowa: Iowa City, IA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Pereda, M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Gómez Del Barrio, A.; Echevarria, S.; Farinas, M.C.; García Palomo, D.; González Macias, J.; Vázquez-Barquero, J.L. Factors associated with neuropsychological performance in HIV-seropositive subjects without AIDS. Psychol. Med. 2000, 30, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, M.; Gilbertson, M.; Mouton, A.; Van Kammen, D. Deterioration in premorbid functioning in schizophrenia: A developmental model of negative symptoms in drug-free patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 1992, 149, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz, J.; De Smedt, G.; Harvey, P.; Davidson, M. Relationship between premorbid functioning and symptom severity as assessed at first episode of psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 2021–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezquida, G.; Cabrera, B.; Bioque, M.; Amoretti, S.; Lobo, A.; González-Pinto, A.; Espliego, A.; Corripio, I.; Vieta, E.; Castro-Fornieles, J.; et al. The course of negative symptoms in first-episode schizophrenia and its predictors: A prospective two-year follow-up study. Schizophr. Res. 2017, 189, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penadés, R.; Catalán, R.; Pujol, N.; Masana, G.; García-Rizo, C.; Bernardo, M. The integration of cognitive remediation therapy into the whole psychosocial rehabilitation process: An evidence-based and person-centered approach. Rehabil. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 386895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bourne, C.; Aydemir, Ö.; Balanzá-Martínez, V.; Bora, E.; Brissos, S.; Cavanagh, J.T.O.; Clark, L.; Cubukcuoglu, Z.; Dias, V.V.; Dittmann, S.; Ferrier, I.N.; et al. Neuropsychological testing of cognitive impairment in euthymic bipolar disorder: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2013, 128, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, B.; Jabben, N.; Krabbendam, L.; van, O.J. Meta-analyses of cognitive functioning in euthymic bipolar patients and their first-degree relatives. Psychol. Med. 2008, 38, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Aran, A.; Vieta, E.; Torrent, C.; Sanchez-Moreno, J.; Goikolea, J.M.; Salamero, M.; Malhi, G.S.; Gonzalez-Pinto, A.; Daban, C.; varez-Grandi, S.; et al. Functional outcome in bipolar disorder: The role of clinical and cognitive factors. Bipolar Disord. 2007, 9, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnín, C.M.; González-Pinto, A.; Solé, B.; Reinares, M.; González-Ortega, I.; Alberich, S.; Crespo, J.M.; Salamero, M.; Vieta, E.; Martínez-Arán, A.; et al. Verbal memory as a mediator in the relationship between subthreshold depressive symptoms and functional outcome in bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 160, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieta, E.; Torrent, C. Functional remediation: The pathway from remission to recovery in bipolar disorder. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 288–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnin, C.M.; Reinares, M.; Martínez-Arán, A.; Balanzá-Martínez, V.; Sole, B.; Torrent, C.; Tabarés-Seisdedos, R.; García-Portilla, M.P.; Ibáñez, A.; Amann, B.L.; et al. Effects of functional remediation on neurocognitively impaired bipolar patients: Enhancement of verbal memory. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnin, C.M.; Torrent, C.; Arango, C.; Amann, B.L.; Solé, B.; González-Pinto, A.; Crespo, J.M.; Tabarés-Seisdedos, R.; Reinares, M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; et al. Functional remediation in bipolar disorder: 1-year follow-up of neurocognitive and functional outcome. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieta, E. Staging and early intervention in bipolar disorder. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 483–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, B.; Jiménez, E.; Torrent, C.; Reinares, M.; Bonnin, C.M.; Torres, I.; Varo, C.; Grande, I.; Valls, E.; Salagre, E.; et al. Cognitive Impairment in Bipolar Disorder: Treatment and Prevention Strategies. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 20, 70–680. [Google Scholar]

- Salagre, E.; Dodd, S.; Aedo, A.; Rosa, A.; Amoretti, S.; Pinzon, J.; Reinares, M.; Berk, M.; Kapczinski, F.P.; Vieta, E.; et al. Toward Precision Psychiatry in Bipolar Disorder: Staging 2.0. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients (n = 100) | Healthy Controls (n = 66) | Statistic | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender: Male N (%) | 65 (65) | 35 (55) | χ2 = 2.378 | 0.084 |

| Age ( ± SD) | 32.68 ± 8.59 | 30.12 ± 8.15 | t = 1.720 | 0.087 |

| SES 1 (%) | χ2 = 5.967 | 0.309 | ||

| High | 30 (30) | |||

| Medium-High | 23 (23) | |||

| Medium | 19 (19) | |||

| Medium-Low | 19 (19) | |||

| Low | 7 (7) | |||

| Missing value | 2 (2) | |||

| Tobacco use: Yes N (%) | 39 (39) | 19 (29) | χ2 = 2.542 | 0.076 |

| Cannabis use: Yes N (%) | 11 (11) | 10 (15) | χ2 =0.372 | 0.352 |

| Functional variables (± SD) | ||||

| GAF 2 score | 74.77 ± 11.94 | 90.79 ± 6.01 | U = 228.50 | <0.001 |

| FAST 3 | 18.64 ± 13.22 | 2.66 ± 6.24 | U = 392.00 | <0.001 |

| Clinical variables (± SD) | ||||

| PANSS 4 positive | 10.54 ± 4.25 | NA 8 | ||

| PANSS negative | 15.90± 6.20 | NA | ||

| PANSS general | 26.82 ± 8.29 | NA | ||

| PANSS total | 53.25 ± 16.89 | NA | ||

| YMRS 5 score | 0.84 ± 1.81 | NA | ||

| MADRS 6 score | 3.90 ± 4.82 | NA | ||

| Neuropsychological performance (± SD) | ||||

| Premorbid IQ 7 | 101.87 ± 11.85 | 108.56 ± 9.48 | t = −3.771 | <0.001 |

| Verbal memory | 41.88 ± 11.45 | 55.25 ± 8.48 | U = 1217.50 | <0.001 |

| Sustained attention | 47.22 ± 13.26 | 45.91 ± 10.87 | t = 0.621 | 0.535 |

| Processing speed | 48.51 ± 11.78 | 61.73 ± 6.27 | U = 134.50 | <0.001 |

| Working memory | 47.15 ± 11.96 | 51.98 ± 9.03 | U = 2188.00 | 0.011 |

| Verbal fluency | 47.60 ± 15.83 | 44.29 ± 17.28 | t = −1.268 | 0.209 |

| Patients (n = 100) | Statistic | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Affective (n = 62) | Affective (n = 38) | |||

| Gender: Male N (%) | 40 (64.52) | 25 (65.79) | χ2 = 0.009 | 0.551 |

| Age ( ± SD) | 30.82 ± 7.74 | 35.71 ± 9.13 | t = −2.578 | 0.011 |

| SES 1 N (%) | χ2 = 7.706 | 0.173 | ||

| High | 21 (34) | 9 (24) | ||

| Medium-High | 13 (21) | 10 (26) | ||

| Medium | 11 (18) | 8 (21) | ||

| Medium-Low | 11 (18) | 8 (21) | ||

| Low | 6 (9) | 1 (3) | ||

| Missing value | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | ||

| Age of onset | 25.67 ± 6 | 25.00 ± 7 | t = 0.489 | 0.626 |

| Tobacco use: Yes N (%) | 22 (35) | 16 (42) | χ2 = 0.201 | 0.407 |

| Cannabis use: Yes N (%) | 7 (11) | 4 (11) | χ2 = 0.077 | 0.526 |

| Functional variables (± SD) | ||||

| GAF 2 score | 74.04 ± 11.66 | 78.57 ± 7.45 | t = −1.366 | 0.177 |

| FAST 3 | 19.19 ± 14.34 | 16.61 ± 11.41 | t =0.838 | 0.405 |

| Clinical variables (± SD) | ||||

| PANSS 4 positive | 11.43 ± 4.48 | 7.86 ± 1.61 | U = 127.00 | 0.001 |

| PANSS negative | 17.24 ± 6.07 | 11.07 ± 3.87 | U = 132.00 | 0.001 |

| PANSS general | 28.11 ± 8.58 | 22.71 ± 6.21 | t = 2.180 | 0.033 |

| PANSS total | 56.76 ± 17.13 | 41.64 ± 10.60 | U = 147.50 | 0.002 |

| YMRS 5 score | 0.73 ± 2.20 | 1.26 ± 1.56 | t = −1.150 | 0.253 |

| MADRS 6 score | 5.17 ± 6.15 | 3.68 ± 3.00 | U = 779.00 | 0.899 |

| Neuropsychological performance (± SD) | ||||

| Premorbid IQ 7 | 98.73 ±11.63 | 107.16 ± 10.35 | t = -3.515 | 0.001 |

| Verbal memory | 38.42 ± 10.16 | 47.06 ± 12.40 | U = 696.50 | 0.002 |

| Sustained attention | 44.77 ± 12.27 | 51.10 ± 14.07 | t = −2.151 | 0.034 |

| Processing speed | 39.85 ± 9.54 | 54.94 ± 8.84 | t = −5.996 | <0.001 |

| Working memory | 45.55 ± 12.32 | 49.78 ± 11.01 | t = −1.713 | 0.090 |

| Verbal fluency | 45.55 ± 16.88 | 46.71 ± 14.06 | t = −0.227 | 0.821 |

| Factor I | Factor II | Factor III | Factor IV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociability | LDG 1 | Leisure Activities | LDG | Occupation | LDG | Education | LDG |

| 10. Social activity in childhood and adolescence | 0.867 | 7. Leisure activities in childhood and adolescence | 0.802 | 5. Training | 0.762 | 1. Education | 0.726 |

| 11. Social activity in adulthood | 0.908 | 8. Leisure activities in adulthood | 0.917 | 6. Employment | 0.890 | 2. Educational attainment of parents | 0.697 |

| 12. Social activity in the past year | 0.923 | 9. Leisure activities in the past year | 0.874 | 3. Scholastic performance | 0.512 | ||

| 4. Languages | 0.558 | ||||||

| Patients | Healthy Controls | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s Correlation CRASH 1 | p-Value | Spearman’s Correlation CRQ 2 | p-Value | Spearman’s Correlation CRASH | p-Value | Spearman’s Correlation CRQ | p-Value | |

| Functional variables (± SD) | ||||||||

| GAF 3 | 0.275 | 0.033 | 0.309 | 0.016 | −0.077 | 0.628 | −0.100 | 0.53 |

| FAST 4 | −0.298 | 0.007 | −0.376 | 0.001 | −0.026 | 0.838 | −0.086 | 0.51 |

| Clinical variables (± SD) | ||||||||

| PANSS 5 positive | −0.333 | 0.002 | −0.455 | <0.001 | NA | |||

| PANSS negative | −0.277 | 0.032 | −0.333 | 0.009 | ||||

| PANSS general | −0.212 | 0.10 | −0.274 | 0.034 | ||||

| PANSS total | −0.280 | 0.030 | −0.363 | 0.004 | ||||

| YMRS 6 score | − 0.070 | 0.376 | −0.058 | 0.61 | ||||

| MADRS 7 score | −0.047 | 0.369 | −0.150 | 0.18 | ||||

| Neuropsychological performance (± SD) | ||||||||

| Premorbid IQ 8 | 0.405 | <0.001 | 0.427 | <0.001 | 0.208 | 0.105 | 0.267 | 0.036 |

| Verbal memory | 0.533 | <0.001 | 0.443 | <0.001 | 0.222 | 0.088 | 0.077 | 0.56 |

| Sustained attention | −0.117 | 0.27 | −0.021 | 0.84 | −0.089 | 0.515 | −0.340 | 0.010 |

| Processing speed | 0.397 | 0.003 | 0.359 | 0.010 | 0.425 | 0.062 | 0.477 | 0.033 |

| Working memory | 0.205 | 0.045 | 0.199 | 0.05 | 0.227 | 0.081 | 0.250 | 0.054 |

| Verbal Fluency | 0.325 | 0.002 | 0.250 | 0.016 | −0.347 | 0.114 | 0.023 | 0.87 |

| Non-Affective (n = 62) | Affective (n = 38) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low CRASH (<37) | High CRASH (≥37) | p | Low CRASH (<45) | High CRASH (≥45) | p | |

| Sociodemographic variables | ||||||

| Gender: Male N (%) | 20 (65) | 20 (65) | 0.64 | 14 (67) | 11 (65) | 0.74 |

| Age ( ± SD) | 29.77 ± 8.07 | 31.87 ± 7.38 | 0.29 | 35.76 ± 9.61 | 35.65 ± 8.79 | 0.97 |

| SES 1 N (%) | 0.43 | 0.19 | ||||

| High | 9 (28) | 12 (40) | 4 (27) | 5 (24) | ||

| Medium-High | 5 (17) | 8 (26) | 4 (27) | 6 (29) | ||

| Medium | 6 (17) | 6 (19) | 3 (20) | 5 (24) | ||

| Medium-Low | 8 (24) | 3 (11) | 3 (20) | 6 (24) | ||

| Low | 5 (15) | 1 (4) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Missing value | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1 (5) | ||

| Age of onset | 25.17 ± 5.88 | 26.11 ± 5.31 | 0.55 | 23.95 ± 6.07 | 25.93 ± 8.85 | 0.43 |

| Functional variables ( ± SD) | ||||||

| GAF 2 | 70.55 ± 11.04 | 76.73 ± 11.61 | 0.06 | 79.50 ± 7 | 76.25 ± 8 | 0.48 |

| FAST 3 | 23.41 ± 14.34 | 15.62 ± 13.60 | 0.07 | 18.55 ± 12 | 13.50 ± 10 | 0.23 |

| Clinical variables ( ± SD) | ||||||

| PANSS 4 positive | 12.71 ± 5.47 | 10.36 ± 3.16 | 0.07 | 8.11 ± 1.97 | 7.40 ± 0.55 | 0.45 |

| PANSS negative | 19.38 ± 6.07 | 15.44 ± 5.58 | 0.027 | 11.56 ± 4.25 | 10.26 ± 3.35 | 0.55 |

| PANSS general | 30.33 ± 9.44 | 26.24 ± 7.46 | 0.10 | 23.22 ± 6.44 | 21.80 ± 6.38 | 0.69 |

| PANSS total | 62.43 ± 18.63 | 52 ± 14.47 | 0.038 | 42.89 ± 11.25 | 39.40 ± 10.11 | 0.58 |

| YMRS 5 | 1.04 ± 3.00 | 0.46 ± 1.17 | 0.37 | 1.52 ± 1.67 | 0.85 ± 1.35 | 0.23 |

| MADRS 6 | 5.32 ± 5.78 | 5.04 ± 6.56 | 0.88 | 3.76 ± 2.95 | 3.54 ± 3.21 | 0.83 |

| Neuropsychological performance ( ± SD) | ||||||

| Premorbid IQ 7 | 93.61 ± 11 | 103.84 ± 10 | <0.001 | 105.71 ± 11.10 | 108.94 ± 9.37 | 0.35 |

| Verbal memory | 34.07 ± 8.43 | 42.50 ± 10.06 | <0.001 | 37.90 ± 11.18 | 53.26 ± 7.82 | <0.001 |

| Sustained attention | 48.68 ± 11.75 | 41.12 ± 11.78 | 0.018 | 51.80 ± 14.86 | 50.26 ± 13.50 | 0.75 |

| Processing speed | 34.50 ± 9.35 | 43.29 ± 8.23 | 0.027 | 54.03 ± 7.48 | 55.67 ± 9.99 | 0.61 |

| Working memory | 43.24 ± 11.82 | 47.86 ± 12.57 | 0.14 | 48.56 ± 11.45 | 51.31 ± 10.59 | 0.46 |

| Verbal fluency | 39.76 ± 16.91 | 51.35 ± 14.99 | 0.008 | 45.55 ± 16.77 | 48.37 ± 9.25 | 0.57 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amoretti, S.; Cabrera, B.; Torrent, C.; Bonnín, C.d.M.; Mezquida, G.; Garriga, M.; Jiménez, E.; Martínez-Arán, A.; Solé, B.; Reinares, M.; et al. Cognitive Reserve Assessment Scale in Health (CRASH): Its Validity and Reliability. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 586. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050586

Amoretti S, Cabrera B, Torrent C, Bonnín CdM, Mezquida G, Garriga M, Jiménez E, Martínez-Arán A, Solé B, Reinares M, et al. Cognitive Reserve Assessment Scale in Health (CRASH): Its Validity and Reliability. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(5):586. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050586

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmoretti, Silvia, Bibiana Cabrera, Carla Torrent, Caterina del Mar Bonnín, Gisela Mezquida, Marina Garriga, Esther Jiménez, Anabel Martínez-Arán, Brisa Solé, Maria Reinares, and et al. 2019. "Cognitive Reserve Assessment Scale in Health (CRASH): Its Validity and Reliability" Journal of Clinical Medicine 8, no. 5: 586. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050586

APA StyleAmoretti, S., Cabrera, B., Torrent, C., Bonnín, C. d. M., Mezquida, G., Garriga, M., Jiménez, E., Martínez-Arán, A., Solé, B., Reinares, M., Varo, C., Penadés, R., Grande, I., Salagre, E., Parellada, E., Bioque, M., Garcia-Rizo, C., Meseguer, A., Anmella, G., ... Bernardo, M. (2019). Cognitive Reserve Assessment Scale in Health (CRASH): Its Validity and Reliability. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(5), 586. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050586