Risk of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide, Population-Based Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Patient Selection

2.2. Data Collection and Study Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Incidence and Risk of Anxiety and Depression in IBD

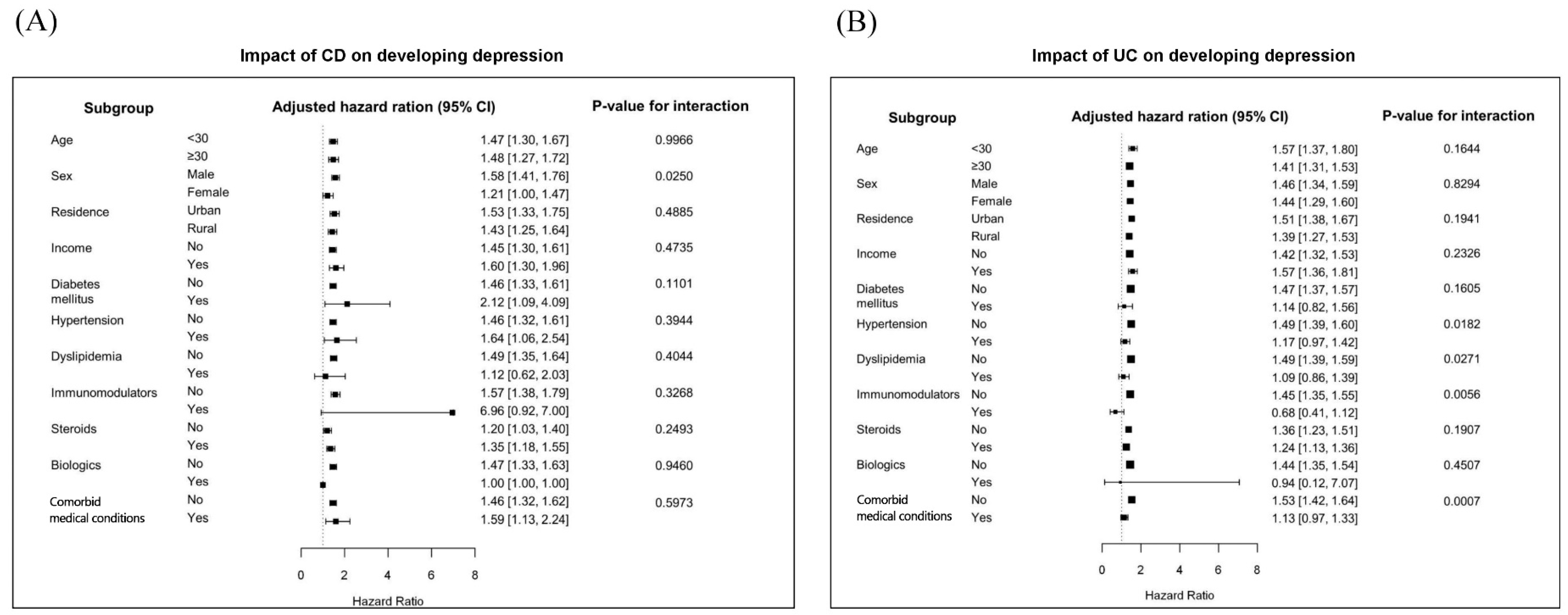

3.3. Subgroup Analyses

3.4. Risk of Anxiety and Depression in IBD Based on Medication Use

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | Crohn’s disease; |

| CI | confidence interval; |

| COPD | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; |

| DM | diabetes mellitus; ESRD; end-stage renal disease; |

| HPA | hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; |

| R | hazard ratio; |

| IBD | inflammatory bowel disease; |

| ICD | international classification of disease; |

| IMID | immune-mediated inflammatory disease; |

| NHIS | national healthcare insurance service; |

| PROM | patient-reported outcome measure; |

| RID | rare intractable disease; |

| SD | standard deviation; |

| UC | ulcerative colitis |

References

- Shin, C.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.; Yoon, S.; Ko, Y.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, S.H.; Jeon, S.W.; Han, C. Prevalence and associated factors of depression in general population of Korea: Results from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2014. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Värnik, P. Suicide in the world. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.J.; Seong, S.J.; Park, J.E.; Chung, I.W.; Lee, Y.M.; Bae, A.; Ahn, J.H.; Lee, D.W.; Bae, J.N.; Cho, S.J. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV mental disorders in South Korean adults: The Korean epidemiologic catchment area study 2011. Psychiatry Investig. 2015, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kwon, J.E.; Cho, M.L. Immunological pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Intest. Res. 2018, 16, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.K.; Yun, S.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Chang, D.K.; Kim, J.S.; Song, I.S.; Park, J.B. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district, Seoul, Korea, 1986–2005: A KASID study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2007, 14, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Hann, H.J.; Hong, S.N.; Kim, K.H.; Ahn, I.M.; Song, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Ahn, H.S. Incidence and natural course of inflammatory bowel disease in Korea, 2006–2012: A nationwide population-based study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knights, D.; Lassen, K.G.; Xavier, R.J. Advances in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis: Linking host genetics and the microbiome. Gut 2013, 62, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao-Kitamoto, H.; Kitamoto, S.; Kuffa, P.; Kamada, N. Pathogenic role of the gut microbiota in gastrointestinal diseases. Intest. Res. 2016, 14, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaz, B.L.; Bernstein, C.N. Brain-gut interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueiro, M.; Greer, J.B.; Szigethy, E. Etiology and Treatment of Pain and Psychosocial Issues in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IsHak, W.W.; Pan, D.; Steiner, A.J.; Feldman, E.; Mann, A.; Mirocha, J.; Danovitch, I.; Melmed, G.Y. Patient-reported outcomes of quality of life, functioning, and GI/psychiatric symptom severity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williet, N.; Sandborn, W.J.; Peyrin–Biroulet, L. Patient-reported outcomes as primary end points in clinical trials of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikocka-Walus, A.; Pittet, V.; Rossel, J.B.; von Känel, R.; Group, S.I.C.S. Symptoms of depression and anxiety are independently associated with clinical recurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipović, B.R.; Filipović, B.F.; Kerkez, M.; Milinić, N.; Ranđelović, T. Depression and anxiety levels in therapy-naive patients with inflammatory bowel disease and cancer of the colon. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häuser, W.; Janke, K.H.; Klump, B.; Hinz, A. Anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Comparisons with chronic liver disease patients and the general population. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Z.; Kovács, F. Depressive and anxiety symptoms, dysfunctional attitudes and social aspects in irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2007, 37, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, R.; Harding, A.; Stello, N.; Hanes, D.; Wahbeh, H. Depression and anxiety in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 87, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrie, R.A.; Walld, R.; Bolton, J.M.; Sareen, J.; Walker, J.R.; Patten, S.B.; Singer, A.; Lix, L.M.; Hitchon, C.A.; El-Gabalawy, R.; et al. Rising incidence of psychiatric disorders before diagnosis of immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2017, 28, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrie, R.A.; Walker, J.R.; Graff, L.A.; Lix, L.M.; Bolton, J.M.; Nugent, Z.; Targownik, L.E.; Bernstein, C.N. Performance of administrative case definitions for depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 89, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikocka-Walus, A.; Knowles, S.R.; Keefer, L.; Graff, L. Controversies Revisited: A Systematic Review of the Comorbidity of Depression and Anxiety with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, L.A.; Walker, J.R.; Bernstein, C.N. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: A review of comorbidity and management. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S. Introduction: Health of the health care system in Korea. Soc. Work Public Health 2010, 25, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.O.; Jung, C.H.; Song, Y.D.; Park, C.Y.; Kwon, H.S.; Cha, B.S.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, K.U.; Ko, K.S.; Lee, B.W. Background and data configuration process of a nationwide population-based study using the Korean National Health Insurance System. Diabetes Metab. J. 2014, 38, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Chun, J.; Han, K.D.; Soh, H.; Choi, K.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.; Lee, C.; Im, J.P.; Kim, J.S. Increased end-stage renal disease risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide population-based study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 4798–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Han, K.; Koh, E.S.; Kim, H.S.; Kwon, H.S.; Park, Y.M.; Yoon, K.H.; Lee, S.H. Variability in Total Cholesterol Is Associated With the Risk of End-Stage Renal Disease: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1963–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.R.; Choi, E.K.; Rhee, T.M.; Lee, H.J.; Lim, W.H.; Kang, S.H.; Han, K.D.; Cha, M.J.; Cho, Y.; Oh, I.Y. Evaluation of the association between diabetic retinopathy and the incidence of atrial fibrillation: A nationwide population-based study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 223, 953–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, H.; Chun, J.; Han, K.; Park, S.; Choi, G.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.; Im, J.P.; Kim, J.S. Increased risk of herpes zoster in young and metabolically healthy patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide population-based study. Gut Liver 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Choi, E.K.; Han, K.D.; Jung, J.H.; Park, J.; Lee, E.; Choe, W.; Lee, S.R.; Cha, M.J.; Lim, W.H. Temporal trends of the prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation and stroke among Asian patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A nationwide population-based study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 273, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. Sibling risk of anxiety disorders based on hospitalizations in Sweden. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 65, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelen, C.; Norder, G.; Koopmans, P.; Van Rhenen, W.; Van Der Klink, J.; Bültmann, U. Employees sick-listed with mental disorders: Who returns to work and when? J. Occup. Rehabil. 2012, 22, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.I.; Sung, N.Y.; Park, S.J.; Lee, C.G.; Lee, B.O. The epidemiology of psychiatric disorders among women with breast cancer in South Korea: Analysis of national registry data. Psychooncology 2014, 23, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurina, L.; Goldacre, M.; Yeates, D.; Gill, L. Depression and anxiety in people with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2001, 55, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Player, M.S.; Peterson, L.E. Anxiety disorders, hypertension, and cardiovascular risk: A review. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2011, 41, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinley, D.J.; Lowry, H.; Katz, C.; Jacobi, F.; Jassal, D.S.; Sareen, J. Depression and anxiety disorders and the link to physician diagnosed cardiac disease and metabolic risk factors. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2015, 37, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker-Collo, S.L. Depression and anxiety 3 months post stroke: Prevalence and correlates. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2007, 22, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, K.; Geist, R.; Goldstein, R.; Lacasse, Y. Anxiety and depression in end-stage COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 31, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroze, U.; Martin, D.; Reina-Patton, A.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kopple, J.D. Mental health, depression, and anxiety in patients on maintenance dialysis. Iran. J. Kidney Dis. 2010, 4, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Linden, W.; Vodermaier, A.; MacKenzie, R.; Greig, D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 141, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navabi, S.; Gorrepati, V.S.; Yadav, S.; Chintanaboina, J.; Maher, S.; Demuth, P.; Stern, B.; Stuart, A.; Tinsley, A.; Clarke, K.; et al. Influences and Impact of Anxiety and Depression in the Setting of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 2303–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, P.R. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015, 40, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, S.F.; Rudich, Z.; Brill, S.; Shalev, H.; Shahar, G. Longitudinal associations between depression, anxiety, pain, and pain-related disability in chronic pain patients. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 77, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, M. Neural mechanisms underlying anxiety–chronic pain interactions. Trends Neurosci. 2016, 39, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgambato, D.; Miranda, A.; Ranaldo, R.; Federico, A.; Romano, M. The role of stress in inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 3997–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, C.N. Psychological stress and depression: Risk factors for IBD? Dig. Dis. 2016, 34, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.R.; Ediger, J.P.; Graff, L.A.; Greenfeld, J.M.; Clara, I.; Lix, L.; Rawsthorne, P.; Miller, N.; Rogala, L.; McPhail, C.M.; et al. The Manitoba IBD cohort study: A population-based study of the prevalence of lifetime and 12-month anxiety and mood disorders. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 1989–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, M.R.; Miller, A.H. Depressive disorders and immunity: 20 years of progress and discovery. Brain Behav. Immun. 2007, 21, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galley, J.D.; Nelson, M.C.; Yu, Z.; Dowd, S.E.; Walter, J.; Kumar, P.S.; Lyte, M.; Bailey, M.T. Exposure to a social stressor disrupts the community structure of the colonic mucosa-associated microbiota. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Gainer, V.S.; Perez, R.G.; Cai, T.; Cheng, S.C.; Savova, G.; Chen, P.; Szolovits, P.; Xia, Z.; De Jager, P.L.; et al. Psychiatric co-morbidity is associated with increased risk of surgery in Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 37, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. (%) | IBD | CD | UC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls ‡ | IBD | p-Value | Controls | CD | p-Value | Controls | UC | p-Value | |

| Events | 46,707 | 15,569 | 19,188 | 6396 | 27,519 | 9173 | |||

| Age, years † | 32.0 ± 13.9 | 32.0 ± 13.9 | 1 | 25.3 ± 10.7 | 25.3 ± 10.7 | 1 | 36.7 ± 13.9 | 36.7 ± 13.9 | 1 |

| <15 | 3054 (6.5) | 1018 (6.5) | 2145 (11.2) | 715 (11.2) | 909 (3.3) | 303 (3.3) | |||

| 15–29 | 25,323 (54.2) | 8441 (54.2) | 13,611 (70.9) | 4537 (70.9) | 11,712 (42.6) | 3904 (42.6) | |||

| 30–44 | 17,505(37.5) | 5835 (37.5) | 3363 (17.5) | 1121 (17.5) | 14,142 (51.4) | 4714 (51.4) | |||

| >45 | 825 (1.8) | 275 (1.8) | 69 (0.4) | 23 (0.4) | 756 (2.7) | 252 (2.7) | |||

| Gender: Male | 34,227 (73.3) | 11,409 (73.3) | 1 | 15,027 (78.3) | 5009 (78.3) | 1 | 19,200 (69.8) | 6400 (69.8) | 1 |

| Residence | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Urban | 21,924 (46.9) | 8125 (52.2) | 9003 (46.9) | 3398 (53.1) | 12,921 (46.9) | 4727 (51.5) | |||

| Rural | 24,783 (53.1) | 7444 (47.8) | 10,185 (53.1) | 2998 (46.9) | 14,598 (53.0) | 4446 (48.5) | |||

| Income * | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Q2-4 | 36,284 (77.7) | 12,678 (81.4) | 14,846 (77.4) | 5123 (80.1) | 21,438 (77.9) | 7555 (82.4) | |||

| Q1 | 10,423 (22.3) | 2891 (18.6) | 4342 (22.6) | 1273 (19.9) | 6081 (22.1) | 1618 (17.6) | |||

| Comorbid medical conditions | |||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1048 (2.2) | 305 (2.0) | 0.035 | 156 (0.8) | 54 (0.8) | 0.810 | 892 (3.2) | 251 (2.7) | 0.016 |

| Hypertension | 2660 (5.7) | 822 (5.3) | 0.051 | 429 (2.2) | 115 (1.8) | 0.036 | 2231 (8.1) | 707 (7.7) | 0.222 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1489 (3.2) | 529 (3.4) | 0.200 | 242 (1.3) | 78 (1.2) | 0.800 | 1247 (4.5) | 451 (4.9) | 0.128 |

| Congestive heart failure | 85 (0.2) | 54 (0.4) | <0.001 | 14 (0.1) | 12 (0.2) | 0.013 | 71 (0.3) | 42 (0.5) | 0.003 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 581 (1.2) | 339 (2.2) | <0.001 | 95 (0.5) | 92 (1.4) | <0.001 | 486 (1.8) | 247 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 1,194 (2.6) | 701 (4.5) | <0.001 | 385 (2.0) | 325 (5.1) | <0.001 | 809 (2.9) | 376 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 462 (1.0) | 181 (1.2) | 0.064 | 79 (0.4) | 30 (0.5) | 0.542 | 383 (1.4) | 151 (1.7) | 0.078 |

| ESRD | 41 (0.1) | 40 (0.3) | <0.001 | 13 (0.1) | 18 (0.3) | <0.001 | 28 (0.1) | 22 (0.2) | 0.002 |

| Malignancy | 355 (0.8) | 179 (1.2) | <0.001 | 68 (0.4) | 36 (0.6) | 0.023 | 287 (1.0) | 143 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Use of therapeutic drugs | |||||||||

| Immunomodulators | 105 (0.2) | 5194 (33.4) | <0.001 | 34 (0.2) | 3865 (60.4) | <0.001 | 71 (0.3) | 1329 (14.5) | <0.001 |

| Steroids | 12,701 (27.2) | 8681 (55.8) | <0.001 | 4895 (25.5) | 3689 (57.7) | <0.001 | 7806 (28.4) | 4992 (54.4) | <0.001 |

| Biologics | 6 (0.01) | 1122 (7.2) | <0.001 | 2 (0.01) | 932 (14.6) | <0.001 | 4 (0.01) | 190 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Events (n) | Follow-Up Duration (person-years) | Incidence Rate (per 1000 person-years) | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | |||||

| Controls | 1301 | 90,912.81 | 14.31 | 1 (Ref) | |

| Prevalent | 617 | 29,589.89 | 20.85 | 1.45 (1.32–1.60) | <0.001 |

| Incident | 236 | 11,300.82 | 20.88 | 1.58 (1.38–1.82) | <0.001 |

| UC | |||||

| Controls | 2779 | 128,958.37 | 21.55 | 1 (Ref) | |

| Prevalent | 1287 | 41,764.84 | 30.82 | 1.44 (1.34–1.53) | <0.001 |

| Incident | 481 | 15,420.67 | 31.19 | 1.58 (1.43–1.74) | <0.001 |

| Events (n) | Follow-Up Duration (person-years) | Incidence Rate (per 1000 person-years) | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | |||||

| Controls | 716 | 92415.12 | 7.75 | 1 (Ref) | |

| Prevalent | 437 | 30048.66 | 14.54 | 1.85 (1.64–2.09) | <0.001 |

| Incident | 171 | 10,864.02 | 14.99 | 2.06 (1.74–2.44) | <0.001 |

| UC | |||||

| Controls | 1495 | 132,419.52 | 11.28 | 1 (Ref) | |

| Prevalent | 807 | 43,276.09 | 18.65 | 1.66 (1.52–1.81) | <0.001 |

| Incident | 312 | 15,890.80 | 19.63 | 1.93 (1.70–2.18) | <0.001 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, K.; Chun, J.; Han, K.; Park, S.; Soh, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.J.; Im, J.P.; Kim, J.S. Risk of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide, Population-Based Study. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050654

Choi K, Chun J, Han K, Park S, Soh H, Kim J, Lee J, Lee HJ, Im JP, Kim JS. Risk of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide, Population-Based Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(5):654. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050654

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Kookhwan, Jaeyoung Chun, Kyungdo Han, Seona Park, Hosim Soh, Jihye Kim, Jooyoung Lee, Hyun Jung Lee, Jong Pil Im, and Joo Sung Kim. 2019. "Risk of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide, Population-Based Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 8, no. 5: 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050654

APA StyleChoi, K., Chun, J., Han, K., Park, S., Soh, H., Kim, J., Lee, J., Lee, H. J., Im, J. P., & Kim, J. S. (2019). Risk of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide, Population-Based Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(5), 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050654