Observed and Expected Survival in Men and Women after Suffering a STEMI

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Selection of the STEMI Sample and Construction of the Reference Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Primary Objectives

- To compare the survival curves of patients with STEMI treated with primary PCI with that of the general population, matching by age, sex, and geographical region.

- To compare the survival curves of patients who survive hospital discharge or first 30 days after the STEMI with that of the general population matching by age, sex, and geographical region.

- To establish differences between men and women in the previous objectives.

- To know if sex is a risk factor for long-term mortality.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- Observed survival is the real survival of the patients who suffered a STEMI and were treated by primary PCI at our institution. To estimate it, the usual Kaplan-Meier analysis was used.

- Expected survival is considered the estimated life expectancy of a person from our region matched for the same characteristics (age and sex) of our STEMI patient. In other words, the theoretical survival of the patients if they had not suffered the STEMI. Its calculation was performed using the Ederer II method, which is the method of choice for the matching [26]. This method uses the mortality rates for different intervals of age, sex, and region provided by the INE [27]. If the expected survival is included in the 95% confidence interval of the observed survival, no differences were considered to exist.

- Relative survival is an estimation of the survival that patients would have in the theoretical assumption that they could only die due to that STEMI or its consequences [25,28]. Its calculation is derived from the rate between the observed survival and the expected survival. For instance, a RS of 100% would indicate that the STEMI had no consequences on survival. Conversely, a RS of 80% during the first year would indicate that 20% (100–80%) of the patients who suffered the STEMI died because of this event or any of its consequences [22,23,24]. Therefore, if the confidence interval of the RS includes 100%, there is no evidence of mortality due to the STEMI and this would indicate that the primary PCI was completely effective in solving the problem [26,28].

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Procedure and Discharge Data

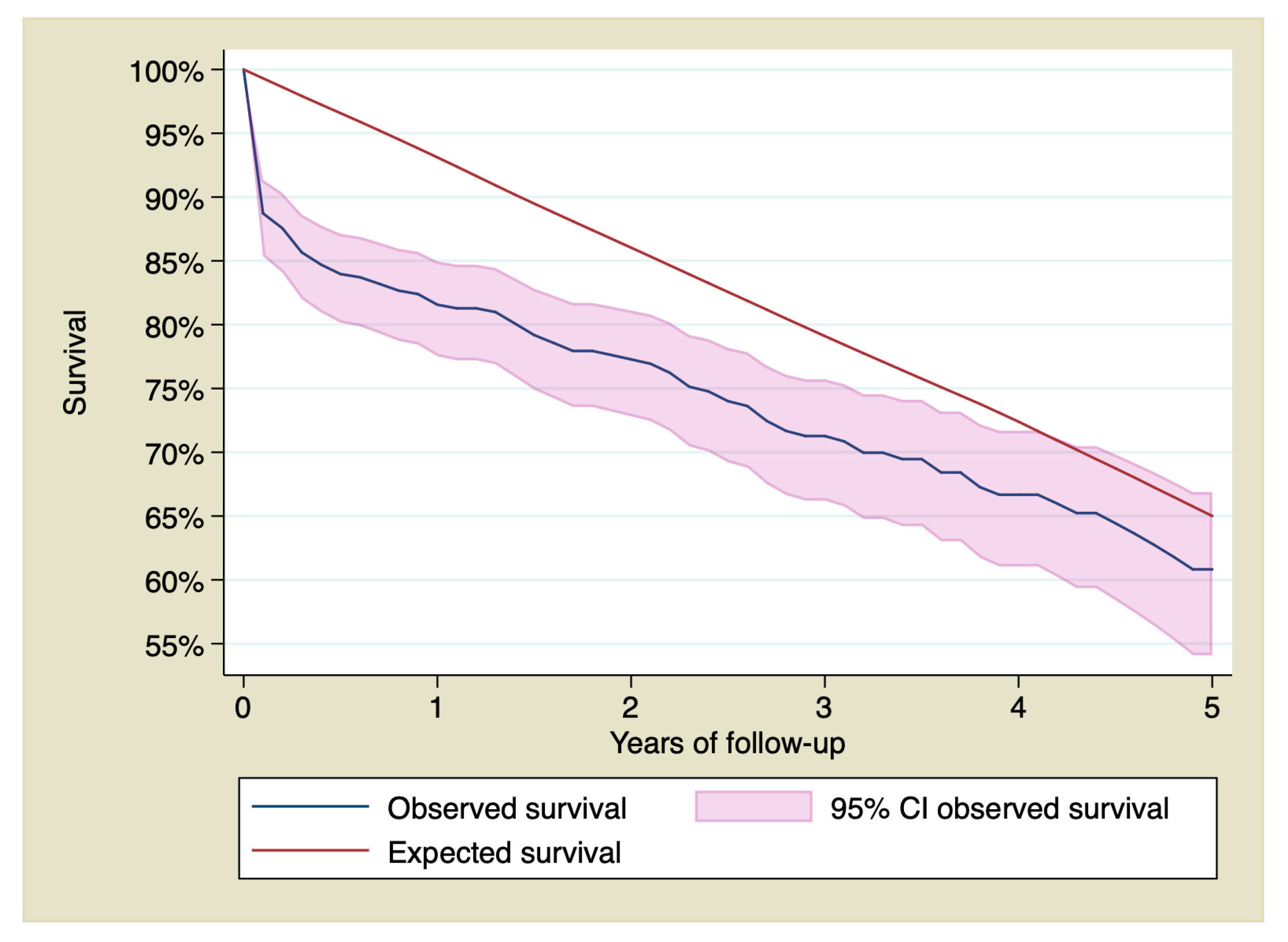

3.3. Observed Survival, Expected Survival, and Relative Survival

3.4. Observed Survival, Expected Survival, and Relative Survival for Patients Who Were Discharged from the Hospital and Were Alive 30 Days after the STEMI

3.5. Influence of Sex on Long-Term Survival

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ibanez, B.; Stefan James, S.; Agewall, S.; Antunes, M.J.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Bueno, H.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Crea, F.; Goudevenos, J.A.; Halvorsen, S.; et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 119–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, C.P.; Allan, V.; Cattle, B.A.; Hall, A.S.; West, R.M.; Timmis, A.; Gray, H.H.; Deanfield, J.; Fox, K.A.A.; Feltbower, R. Trends in hospital treatments, including revascularization, following acute myocardial infarction, 2003–2010: A multilevel and relative survival analysis for the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR). Heart 2014, 100, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, F.; Butrymovich, V.; Kelbæk, H.; Wachtell, K.; Helqvist, S.; Kastrup, J.; Holmvang, L.; Clemmensen, P.; Engstrøm, T.; Grande, P.; et al. Short- and Long-Term Cause of Death in Patients Treated With Primary PCI for STEMI. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 2101–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokkema, M.L.; James, S.; Thorvinger, B.; Lagerqvist, B.; Albertsson, P.; Åkerblom, A.; Calais, F.; Eriksson, P.; Jensen, J.; Nilsson, T.; et al. Population Trends in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: 20-year results from the SCAAR (Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochar, A.; Chen, A.Y.; Sharma, P.P.; Pagidipati, N.J.; Fonarow, G.C.; Cowper, P.A.; Roe, M.T.; Peterson, E.D.; Wang, T.Y. Long-Term Mortality of Older Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction Treated in US Clinical Practice. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e007230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontis, V.; Bennett, J.E.; Mathers, C.D.; Li, G.; Foreman, K.; Ezzati, M. Future life expectancy in 35 industrialized countries: projections with a Bayesian model ensemble. Lancet 2017, 389, 1323–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EUGenMed; Cardiovascular Clinical Study Group; Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Oertelt-Prigione, S.; Prescott, E.; Franconi, F.; Gerdts, E.; Foryst-Ludwig, A.; Maas, A.H.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; et al. Gender in cardiovascular diseases: Impact on clinical manifestations, management, and outcomes. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 37, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, D.; Eagle, K.A.; Goodman, S.G.; Steg, P.G.; Budaj, A.; White, K.; Montalescot, G. Acute Coronary Syndromes Without Chest Pain, An Underdiagnosed and Undertreated High-Risk Group: Insights from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Chest 2004, 126, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaul, P.; Armstrong, P.W.; Sookram, S.; Leung, B.K.; Brass, N.; Welsh, R.C. Temporal trends in patient and treatment delay among men and women presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J. 2011, 161, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diercks, D.B.; Owen, K.P.; Kontos, M.C.; Blomkalns, A.; Chen, A.Y.; Miller, C.; Wiviott, S.; Peterson, E.D. Gender differences in time to presentation for myocardial infarction before and after a national women’s cardiovascular awareness campaign: A temporal analysis from the Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress ADverse Outcomes with Early Implementation (CRUSADE) and the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network–Get with the Guidelines (NCDR ACTION Registry–GWTG). Am. Heart J. 2010, 160, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccarino, V.; Parsons, L.; Peterson, E.D.; Rogers, W.J.; Kiefe, C.I.; Canto, J. Sex Differences in Mortality After Acute Myocardial Infarction: Changes from 1994 to 2006. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 1767–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccarino, V.; Parsons, L.; Every, N.R.; Barron, H.V.; Krumholz, H.M. Sex-Based Differences in Early Mortality after Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvelplund, A.; Galatius, S.; Madsen, M.; Rasmussen, J.N.; Sand, N.P.; Tilsted, H.-H.; Thayssen, P.; Sindby, E.; Højbjerg, S.; Abildstrøm, S.Z. Women with acute coronary syndrome are less invasively examined and subsequently less treated than men. Eur. Heart J. 2009, 31, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.T.; Berger, A.K.; Duval, S.; Luepker, R.V. Gender disparity in cardiac procedures and medication use for acute myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J. 2008, 155, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Torbal, A.; Boersma, E.; Kors, J.A.; Van Herpen, G.; Deckers, J.W.; Van Der Kuip, D.A.; Stricker, B.H.; Hofman, A.; Witteman, J.C. Incidence of recognized and unrecognized myocardial infarction in men and women aged 55 and older: The Rotterdam Study. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.S.; Elliott, L.; Gallup, D.; Roe, M.; Granger, C.B.; Armstrong, P.W.; Simes, R.J.; White, H.D.; Van De Werf, F.; Topol, E.J.; et al. Sex Differences in Mortality Following Acute Coronary Syndromes. JAMA 2009, 302, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtman, J.H.; Wang, Y.; Jones, S.B.; Leifheit-Limson, E.C.; Shaw, L.J.; Vaccarino, V.; Rumsfeld, J.S.; Krumholz, H.M.; Curtis, J.P. Age and sex differences in inhospital complication rates and mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention procedures: Evidence from the NCDR®. Am. Heart J. 2014, 167, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, S.; Kolte, D.; Gupta, T.; Subramanian, K.S.; Khanna, N.; Aronow, W.S.; Ahn, C.; Timmermans, R.J.; Cooper, H.A.; Fonarow, G.C.; et al. Temporal trends and sex differences in evascularization and outcomes of st-segment elevation myocardial infarction in younger adults in the United States. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 1961–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawesson, S.S.; Alfredsson, J.; Fredrikson, M.; Swahn, E. A gender perspective on short- and long term mortality in ST-elevation myocardial infarction—A report from the SWEDEHEART register. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heer, T.; Hochadel, M.; Schmidt, K.; Mehilli, J.; Zahn, R.; Kuck, K.; Hamm, C.; Böhm, M.; Ertl, G.; Hoffmeister, H.M.; et al. Sex Differences in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention—Insights From the Coronary Angiography and PCI Registry of the German Society of Cardiology. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e004972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.S.; Brown, D.L. Gender–Age Interaction in Early Mortality Following Primary Angioplasty for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2006, 98, 1140–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, I.; Hernandez-Vaquero, D.; Alperi, A.; Avanzas, P.; Díaz, R.; Moris, C.; Silva, J. Survival in elderly patients with transcatheter aortic valve implants compared with the general population. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Vaquero, D.; Silva, J.; Escalera, A.; Álvarez-Cabo, R.; Morales, C.; Díaz, R.; Avanzas, P.; Moris, C.; Pascual, I. Life Expectancy after Surgery for Ascending Aortic Aneurysm. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, N.; Persson, M.; Jackson, V.; Holzmann, M.J.; Franco-Cereceda, A.; Sartipy, U. Loss in Life Expectancy After Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement: SWEDEHEART Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickman, P.; Coviello, E. Estimating and Modeling Relative Survival. Stata J. 2015, 15, 186–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakulinen, T.; Seppä, K.; Lambert, P. Choosing the relative survival method for cancer survival estimation. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 2202–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Tablas De Mortalidad Por Año, Provincias, Sexo, Edad Y Funciones. Available online: http://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=27154 Consultado el 03 de abril del 2019 (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Mariotto, A.B.; Noone, A.-M.; Howlader, N.; Cho, H.; Keel, G.E.; Garshell, J.; Woloshin, S.; Schwartz, L.M. Cancer Survival: An Overview of Measures, Uses, and Interpretation. JNCI Monogr. 2014, 2014, 145–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.M.; Cattle, B.A.; Bouyssie, M.; Squire, I.; De Belder, M.; Fox, K.A.; Boyle, R.; McLenachan, J.M.; Batin, P.D.; Greenwood, D.C.; et al. Impact of hospital proportion and volume on primary percutaneous coronary intervention performance in England and Wales. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 32, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, E.C.; Boura, J.A.; Grines, C.L. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: A quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet 2003, 361, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenko, E.; Yoon, J.; Van Der Schaar, M.; Badimón, L.; Bugiardini, R.; Kedev, S.; Stankovic, G.; Vasiljevic, Z.; Krljanac, G.; Kalpak, O.; et al. Sex Differences in Outcomes After STEMI: Effect Modification by Treatment Strategy and Age. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venetsanos, D.; Lawesson, S.S.; Alfredsson, J.; Janzon, M.; Cequier, A.; Chettibi, M.; Goodman, S.G.; Hof, A.W.V.; Montalescot, G.; Swahn, E. Association between gender and short-term outcome in patients with ST elevation myocardial infraction participating in the international, prospective, randomised Administration of Ticagrelor in the catheterisation Laboratory or in the Ambulance for New ST elevation myocardial Infarction to open the Coronary artery (ATLANTIC) trial: A prespecified analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Male (n = 263) | Female (n = 187) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 81.6 ± 4.7 | 83.1 ± 4.8 | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 152 (57.8%) | 132 (70.6%) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes | 84 (31.9%) | 52 (27.8%) | 0.347 |

| Dyslipidemia | 116 (44.1%) | 69 (36.8%) | 0.126 |

| Smoking Habit | 117 (44.5%) | 18 (9.6%) | 0.001 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 38 (14.4%) | 24 (12.8%) | 0.624 |

| Previous Myocardial Infarction | 54 (20.5%) | 22 (11.8%) | 0.014 |

| Previous PCI | 39 (14.8%) | 18 (9.7%) | 0.102 |

| Previous CABG | 12 (4.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.003 |

| Variable | Male (n = 263) | Female (n = 187) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access: | 0.894 | ||

| Femoral | 113 (42.9%) | 81 (42.8%) | |

| Radial | 148 (56.3%) | 106 (56.7%) | |

| Braquial | 2 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Culprit Artery: | 0.147 | ||

| Left Main | 13 (4.9%) | 3 (1.6%) | |

| LAD | 132 (50.2%) | 86 (46%) | |

| LCX | 39 (14.8%) | 37 (19.8%) | |

| RCA | 75 (28.5%) | 61 (32.6%) | |

| Graft | 4 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Multivessel Disease | 141 (53.6%) | 72 (38.5%) | 0.002 |

| Stents Implanted | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 0.501 |

| IABP | 14 (5.3%) | 11 (5.9%) | 0.799 |

| Failed PCI | 11 (4.2%) | 8 (4.3%) | 0.960 |

| Killip Kimball Class | 0.684 | ||

| I | 182 (69.2%) | 126 (67.4%) | |

| II | 39 (14.8%) | 31 (16.6%) | |

| III | 16 (6.1%) | 8 (4.3%) | |

| IV | 26 (9.9%) | 22 (11.8%) | |

| Vascular Complications | 4 (1.5%) | 5 (2.7%) | 0.389 |

| Arrhythmia | 15 (5.7%) | 10 (5.3%) | 0.871 |

| Endotracheal Intubation | 4 (1.5%) | 7 (3.7%) | 0.132 |

| US TnT (pg/mL) | 6175 ± 547 | 5112 ± 507 | 0.169 |

| LVEF at Discharge | 48.93 ± 11.3 | 49.56 ± 11.5 | 0.584 |

| CI-AKI | 61 (23.2%) | 48 (25.7%) | 0.546 |

| Procedural Death | 3 (1.1.%) | 4 (2.1%) | 0.399 |

| Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Deaths < 30 days (n = 59) | Male (n = 31) | Female (n = 28) |

| Cardiovascular | 25 (80.7%) | 25 (89.3%) |

| Stroke | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.6%) |

| Major Bleeding | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Infection | 1(3.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Others | 5 (16.1%) | 2 (7.1%) |

| Deaths after Discharge or >30 days (n = 82) | Male (n = 55) | Female (n = 27) |

| Cardiovascular | 16 (29.1%) | 11 (40.7%) |

| Stroke | 4 (7.2%) | 4 (14.8%) |

| Major Bleeding | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| Sepsis | 6 (10.9%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Respiratory Infection | 6 (10.9%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Cancer | 5 (9.1%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Unknown | 5 (9.1%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| Others | 13 (23.6%) | 4 (14.8%) |

| Year of Follow-Up | Cumulative Survival of Patients with STEMI (Observed Survival) | Cumulative Survival in the Reference Group (Expected Survival) | Annual Relative Survival * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||

| First Year | 82.39% (CI 95% 77.05–86.59) | 92.51% | 88.06% (CI 95% 82.15–92.73) |

| Second Year | 76.93% (CI 95% 70.96–81.83) | 84.55% | 101.77% (CI 95% 96.28–104.94) |

| Third Year | 69.71% (CI 95% 62.95–75.48%) | 76.86% | 99.27% (CI 95% 92.16–103.55) |

| Fourth Year | 65.03% (CI 95% 57.67–71.43) | 69.74% | 102.37% (CI 95% 93.92–106.4) |

| Fifth Year | 60.26% (CI 95% 51.97–67.58%) | 62.06% | 102.96% (CI 95% 89.99–108.3) |

| Women | |||

| First Year | 80.44% (CI 95% 73.60–85.62) | 94.06% | 83.89% (CI 95% 76.31–89.75) |

| Second Year | 78.01% (CI 95% 70.85–83.62) | 88.43% | 103.06% (CI 95% 96.73–105.19) |

| Third Year | 74% (CI 95% 66.04–80.37) | 82.81% | 100.99% (CI 95% 92.67–104.3) |

| Fourth Year | 69.54% (CI 95% 60.34–77.01) | 77.56% | 101.02% (CI 95% 89.27–105.13) |

| Fifth Year | 61.57% (CI 95% 49.24–71.74) | 70.27% | 97.41% (CI 95% 77.10–105.03) |

| Year of Follow-Up | Cumulative Survival of Patients with STEMI (Observed Survival) | Cumulative Survival in the Reference Population (Expected Survival) | Annual Relative Survival * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||

| First Year | 91.70% (CI 95% 87.14–94.69) | 92.51% | 98.65% (CI 95% 93.71–101.90) |

| Second Year | 85.63% (CI 95% 79.92–89.81) | 84.56% | 101.77% (CI 95% 96.28–104.94) |

| Third Year | 77.59% (CI 95% 70.64–83.09) | 76.86% | 99.27% (CI 95% 92.16–103.55) |

| Fourth Year | 72.38% (CI 95% 64.59–78.74) | 69.74% | 102.37% (CI 95% 93.92–106.4) |

| Fifth Year | 67.07% (CI 95% 58.06–74.57) | 62.07% | 102.96% (CI 95% 89.99–108.3) |

| Women | |||

| First Year | 90.59% (CI 95% 84.59–94.33) | 94.05%, | 95.82% (CI 95% 89.18–99.98) |

| Second Year | 87.85% (CI 95% 81.07–92.32) | 88.42% | 103.06% (CI 95% 96.73–105.19) |

| Third Year | 83.33% (CI 95% 75.23–88.98) | 82.81% | 100.99% (CI 95% 92.67–104.3) |

| Fourth Year | 78.31% (CI 95% 68.38–85.45) | 76.89% | 101.02% (CI 95% 89.27–105.13) |

| Fifth Year | 69.34% (CI 95% 55.30–79.75) | 70.16% | 97.41% (CI 95% 77.10–105.03) |

| Variable | HR | 95% Confidence Interval | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.02 | 0.67–1.53 | 0.920 |

| Age | 1.06 | 1.02–1.1 | 0.004 |

| Diabetes | 0.93 | 0.63–1.38 | 0.720 |

| Hypertension | 1.19 | 0.80–1.78 | 0.390 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.74 | 0.49–1.1 | 0.140 |

| Smoking History | 1.23 | 0.81–1.88 | 0.340 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 1.54 | 1.01–2.30 | 0.046 |

| Previous Myocardial Infarction | 0.66 | 0.32–1.35 | 0.250 |

| Previous Coronary Angioplasty | 1.19 | 0.53–2.71 | 0.660 |

| Previous Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery | 2.34 | 0.98–5.74 | 0.054 |

| Lesion on Anterior Descending Artery | 0.95 | 0.66–1.39 | 0.800 |

| III or IV Killip Class | 5.14 | 3.41–7.75 | <0.001 |

| Multivessel Diseas | 1.09 | 0.76–1.58 | 0.630 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pascual, I.; Hernandez-Vaquero, D.; Almendarez, M.; Lorca, R.; Escalera, A.; Díaz, R.; Alperi, A.; Carnero, M.; Silva, J.; Morís, C.; et al. Observed and Expected Survival in Men and Women after Suffering a STEMI. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9041174

Pascual I, Hernandez-Vaquero D, Almendarez M, Lorca R, Escalera A, Díaz R, Alperi A, Carnero M, Silva J, Morís C, et al. Observed and Expected Survival in Men and Women after Suffering a STEMI. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(4):1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9041174

Chicago/Turabian StylePascual, Isaac, Daniel Hernandez-Vaquero, Marcel Almendarez, Rebeca Lorca, Alain Escalera, Rocío Díaz, Alberto Alperi, Manuel Carnero, Jacobo Silva, Cesar Morís, and et al. 2020. "Observed and Expected Survival in Men and Women after Suffering a STEMI" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 4: 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9041174

APA StylePascual, I., Hernandez-Vaquero, D., Almendarez, M., Lorca, R., Escalera, A., Díaz, R., Alperi, A., Carnero, M., Silva, J., Morís, C., & Avanzas, P. (2020). Observed and Expected Survival in Men and Women after Suffering a STEMI. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(4), 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9041174