Psychiatric Aspects of Obesity: A Narrative Review of Pathophysiology and Psychopathology

Abstract

:1. Introduction

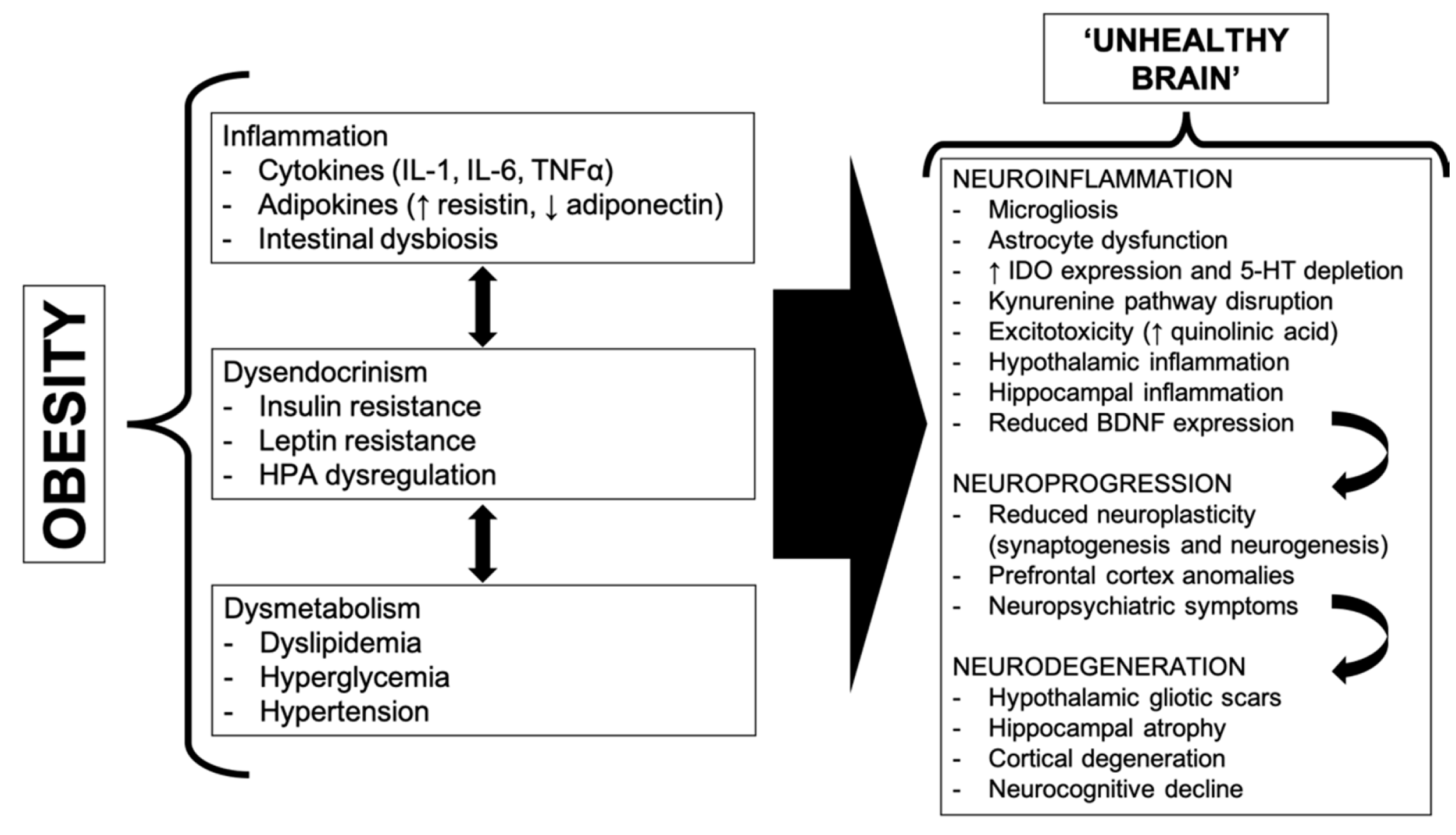

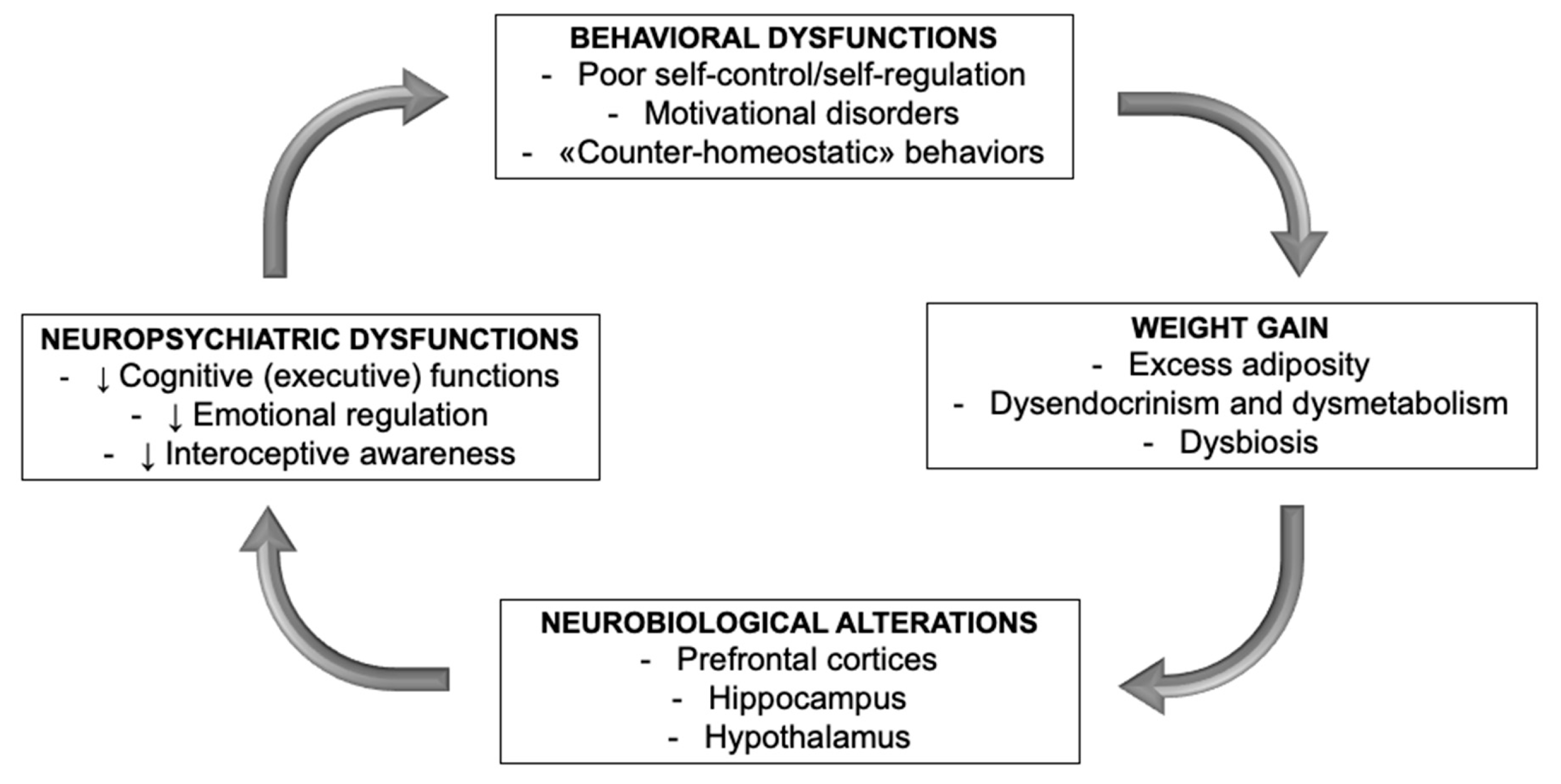

2. A Bidirectional Relationship

3. Obesity as a Result of an Eating Disorder

4. Mood Disorders and Obesity

5. ADHD and Obesity

6. An Affective-Temperamental Framework for Obesity

7. Executive Dysfunctions, Impulsivity and Emotional Dysregulation Are Involved in Obesogenesis

8. A Motivational Contribution: Eating and Food Addiction

9. Is There a Common Thread?

10. Limitations

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heymsfield, S.B.; Wadden, T.A. Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Management of Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blüher, M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chooi, Y.C.; Ding, C.; Magkos, F. The epidemiology of obesity. Metabolism 2019, 92, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Durrer Schutz, D.; Busetto, L.; Dicker, D.; Farpour-Lambert, N.; Pryke, R.; Toplak, H.; Widmer, D.; Yumuk, V.; Schutz, Y. European Practical and Patient-Centred Guidelines for Adult Obesity Management in Primary Care. Obes. Facts 2019, 12, 40–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpiniello, B.; Pinna, F.; Pillai, G.; Nonnoi, V.; Pisano, E.; Corrias, S.; Orru, M.G.; Orru, W.; Velluzzi, F.; Loviselli, A. Obesity and psychopathology. A study of psychiatric comorbidity among patients attending a specialist obesity unit. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2009, 18, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopresti, A.L.; Drummond, P.D. Obesity and psychiatric disorders: Commonalities in dysregulated biological pathways and their implications for treatment. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 45, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castanon, N.; Lasselin, J.; Capuron, L. Neuropsychiatric comorbidity in obesity: Role of inflammatory processes. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shefer, G.; Marcus, Y.; Stern, N. Is obesity a brain disease? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 2489–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapelberg, N.J.C.; Neumann, D.; Shum, D.; Mcconnell, H.; Hamilton-Craig, I. From Physiome to Pathome: A Systems Biology Model of Major Depressive Disorder and the Psycho-Immune-Neuroendocrine Network. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2015, 11, 32–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patist, C.M.; Stapelberg, N.J.C.; Du Toit, E.F.; Headrick, J.P. The brain-adipocyte-gut network: Linking obesity and depression subtypes. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 18, 1121–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebb, S.A.; Prentice, A.M. Is obesity an eating disorder? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1995, 54, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jemma, D.A.Y.; Ternouth, A.; Collier, D.A. Eating disorders and obesity: Two sides of the same coin? Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2009, 18, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raman, J.; Smith, E.; Hay, P. The clinical obesity maintenance model: An integration of psychological constructs including mood, emotional regulation, disordered overeating, habitual cluster behaviours, health literacy and cognitive function. J. Obes. 2013, 2013, 240128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, K.; Thanos, P.K.; Gold, M.S. Dopamine and glucose, obesity and reward deficiency syndrome. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Velasco, R.M.; Barbudo, E.; Pérez-Templado, J.; Silveira, B.; Quintero, J. Review of the association between obesity and ADHD. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2015, 43, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ziauddeen, H.; Alonso-Alonso, M.; Hill, J.O.; Kelley, M.; Khan, N.A. Obesity and the neurocognitive basis of food reward and the control of intake. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCuen-Wurst, C.; Ruggieri, M.; Allison, K.C. Disordered eating and obesity: Associations between binge-eating disorder, night-eating syndrome, and weight-related comorbidities. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1411, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.F.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Karam, A.M.; Jakubiak, J.; Brown, M.L.; Wilfley, D.E. Disordered Eating Attitudes and Behaviors in Youth with Overweight and Obesity: Implications for Treatment. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2018, 7, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könner, A.C.; Brüning, J.C. Selective Insulin and Leptin Resistance in Metabolic Disorders. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farr, O.M.; Li, C.-S.R.; Mantzoros, C.S. Central nervous system regulation of eating: Insights from human brain imaging. Metabolism 2016, 65, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- da Luz, F.Q.; Hay, P.; Touyz, S.; Sainsbury, A. Obesity with Comorbid Eating Disorders: Associated Health Risks and Treatment Approaches. Nutrients 2018, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vaidya, V.; Malik, A. Eating disorders related to obesity. Therapy 2008, 5, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarejo, C.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Peñas-Lledó, E.; Granero, R.; Penelo, E.; Tinahones, F.J.; Sancho, C.; Vilarrasa, N.; Montserrat-Gil De Bernabé, M.; et al. Lifetime obesity in patients with eating disorders: Increasing prevalence, clinical and personality correlates. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2012, 20, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lebow, J.; Sim, L.A.; Kransdorf, L.N. Prevalence of a history of overweight and obesity in adolescents with restrictive eating disorders. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2015, 56, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koritar, P.; Pinzon, V.D.; Barros, C.; Cobelo, A.; Fleitlich-Bilyk, B. Anorexia nervosa: Differences and similarities between adolescents with and without a history of obesity. Rev. Mex. Trastor. Aliment. 2014, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herzog, D.B.; Keller, M.B.; Lavori, P.W. Outcome in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. A review of the literature. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1988, 176, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Strien, T. Causes of Emotional Eating and Matched Treatment of Obesity. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2018, 18, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaplan, H.I.; Kaplan, H.S. The psychosomatic concept of obesity. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1957, 125, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, W. Eating Disorders: Obesity, Anorexia Nervosa, and the Person Within. JAMA 1973, 225, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, S. Obesity and eating. Internal and external cues differentially affect the eating behavior of obese and normal subjects. Science 1968, 161, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, S.; Goldman, R.; Gordon, A. Effects of fear, food deprivation, and obesity on eating. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 10, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canetti, L.; Bachar, E.; Berry, E.M. Food and emotion. Behav. Processes 2002, 60, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianini, L.M.; White, M.A.; Masheb, R.M. Eating pathology, emotion regulation, and emotional overeating in obese adults with binge eating disorder. Eat. Behav. 2013, 14, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dingemans, A.; Danner, U.; Parks, M. Emotion Regulation in Binge Eating Disorder: A Review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Segura-Garcia, C.; Caroleo, M.; Rania, M.; Barbuto, E.; Sinopoli, F.; Aloi, M.; Arturi, F.; De Fazio, P. Binge Eating Disorder and Bipolar Spectrum disorders in obesity: Psychopathological and eating behaviors differences according to comorbidities. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 208, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, M.; Schmidt, R.; Hilbert, A. Executive Functioning in Obesity, Food Addiction, and Binge-Eating Disorder. Nutrients 2018, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tamiya, H.; Ouchi, A.; Chen, R.; Miyazawa, S.; Akimoto, Y.; Kaneda, Y.; Sora, I. Neurocognitive Impairments Are More Severe in the Binge-Eating/Purging Anorexia Nervosa Subtype Than in the Restricting Subtype. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Succurro, E.; Segura-Garcia, C.; Ruffo, M.; Caroleo, M.; Rania, M.; Aloi, M.; de Fazio, P.; Sesti, G.; Arturi, F. Obese Patients With a Binge Eating Disorder Have an Unfavorable Metabolic and Inflammatory Profile. Medicine 2015, 94, e2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassenaar, E.; Friedman, J.; Mehler, P.S. Medical Complications of Binge Eating Disorder. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 42, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raevuori, A.; Suokas, J.; Haukka, J.; Gissler, M.; Linna, M.; Grainger, M.; Suvisaari, J. Highly increased risk of type 2 diabetes in patients with binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Abbasi, O.; Malevanchik, L.; Mohan, N.; Denicola, R.; Tarangelo, N.; Marzio, D.H.-D. Pilot study of the prevalence of binge eating disorder in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2017, 30, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.A.; Chiu, W.T.; Deitz, A.C.; Hudson, J.I.; Shahly, V.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Benjet, C.; et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McElroy, S.L.; Kotwal, R.; Malhotra, S.; Nelson, E.B.; Keck, P.E.; Nemeroff, C.B. Are mood disorders and obesity related? A review for the mental health professional. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65, 634–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadalla, T.M. Association of obesity with mood and anxiety disorders in the adult general population. Chronic Dis. Can. 2009, 30, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soczynska, J.K.; Kennedy, S.H.; Woldeyohannes, H.O.; Liauw, S.S.; Alsuwaidan, M.; Yim, C.Y.; McIntyre, R.S. Mood disorders and obesity: Understanding inflammation as a pathophysiological nexus. Neuromol. Med. 2011, 13, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Keck, P.E.J. Obesity in bipolar disorder: An overview. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2012, 14, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Guerdjikova, A.I.; Mori, N.; Keck, P.E. Managing comorbid obesity and depression through clinical pharmacotherapies. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2016, 17, 1599–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, R.B.; Brietzke, E.; McIntyre, R.S. Is there a “metabolic-mood syndrome”? A review of the relationship between obesity and mood disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 52, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, G.E.; Von Korff, M.; Saunders, K.; Miglioretti, D.L.; Crane, P.K.; van Belle, G.; Kessler, R.C. Association Between Obesity and Psychiatric Disorders in the US Adult Population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luppino, F.S.; de Wit, L.M.; Bouvy, P.F.; Stijnen, T.; Cuijpers, P.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Zitman, F.G. Overweight, Obesity, and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugi, G.; Fornaro, M.; Akiskal, H.S. Are atypical depression, borderline personality disorder and bipolar II disorder overlapping manifestations of a common cyclothymic diathesis? World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. 2011, 10, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasserre, A.M.; Glaus, J.; Vandeleur, C.L.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Vaucher, J.; Bastardot, F.; Waeber, G.; Vollenweider, P.; Preisig, M. Depression with atypical features and increase in obesity, body mass index, waist circumference, and fat mass: A prospective, population-based study. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lojko, D.; Buzuk, G.; Owecki, M.; Ruchala, M.; Rybakowski, J.K. Atypical features in depression: Association with obesity and bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 185, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratt, L.A.; Brody, D.J. Depression and Obesity in the U.S. Adult Household Population, 2005–2010; NCHS Data Brief; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2014; pp. 1–8.

- Perugi, G.; Akiskal, H.S.; Lattanzi, L.; Cecconi, D.; Mastrocinque, C.; Patronelli, A.; Vignoli, S.; Bemi, E. The high prevalence of “soft” bipolar (II) features in atypical depression. Compr. Psychiatry 1998, 39, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.I.; Birmaher, B.; Axelson, D.A.; Goldstein, T.R.; Esposito-Smythers, C.; Strober, M.A.; Hunt, J.; Leonard, H.; Gill, M.K.; Iyengar, S.; et al. Preliminary findings regarding overweight and obesity in pediatric bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69, 1953–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldstein, B.I.; Liu, S.-M.; Zivkovic, N.; Schaffer, A.; Chien, L.-C.; Blanco, C. The burden of obesity among adults with bipolar disorder in the United States. Bipolar Disord. 2011, 13, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, N.M.; Barry, D.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Wagner, J.A. Overweight and obesity are associated with psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosom. Med. 2008, 70, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, G.; Salvi, V.; Vitalucci, A.; D’Ambrosio, V.; Bogetto, F. Prevalence and correlates of overweight in drug-naive patients with bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 110, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaro, M.; Perugi, G.; Gabrielli, F.; Prestia, D.; Mattei, C.; Vinciguerra, V.; Fornaro, P. Lifetime co-morbidity with different subtypes of eating disorders in 148 females with bipolar disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 121, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; McElroy, S.L.; Konarski, J.Z.; Soczynska, J.K.; Bottas, A.; Castel, S.; Wilkins, K.; Kennedy, S.H. Substance use disorders and overweight/obesity in bipolar I disorder: Preliminary evidence for competing addictions. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 68, 1352–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, H.R. Major depressive disorder is associated with broad impairments on neuropsychological measures of executive function: A meta-analysis and review. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 81–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Woo, Y.S.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Kakar, R.; Bahk, W.-M.; McIntyre, R.S. Cognitive Deficits as a Mediator of Poor Occupational Function in Remitted Major Depressive Disorder Patients. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2016, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paelecke-Habermann, Y.; Pohl, J.; Leplow, B. Attention and executive functions in remitted major depression patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 89, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visted, E.; Vøllestad, J.; Nielsen, M.B.; Schanche, E. Emotion Regulation in Current and Remitted Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fagiolini, A.; Kupfer, D.J.; Houck, P.R.; Novick, D.M.; Frank, E. Obesity as a Correlate of Outcome in Patients With Bipolar I Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, D.E.; Gao, K.; Chan, P.K.; Ganocy, S.J.; Findling, R.L.; Calabrese, J.R. Medical comorbidity in bipolar disorder: Relationship between illnesses of the endocrine/metabolic system and treatment outcome. Bipolar Disord. 2010, 12, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woo, Y.S.; Seo, H.-J.; McIntyre, R.S.; Bahk, W.-M. Obesity and Its Potential Effects on Antidepressant Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Depressive Disorders: A Literature Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Cornelius, J.R.; Han, X.; Pincus, H.A.; Shad, M.; Salloum, I.; Conigliaro, J.; Haas, G.L. Burden of general medical conditions among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2004, 6, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.I.; Schaffer, A.; Wang, S.; Blanco, C. Excessive and premature new-onset cardiovascular disease among adults with bipolar disorder in the US NESARC cohort. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 76, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, C.Y.; Soczynska, J.K.; Kennedy, S.H.; Woldeyohannes, H.O.; Brietzke, E.; McIntyre, R.S. The effect of overweight/obesity on cognitive function in euthymic individuals with bipolar disorder. Eur. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perugi, G.; Akiskal, H.S. The soft bipolar spectrum redefined: Focus on the cyclothymic, anxious-sensitive, impulse-dyscontrol, and binge-eating connection in bipolar II and related conditions. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2002, 25, 713–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandra Kooij, J.J. ADHD and obesity. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Altfas, J.R. Prevalence of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults in obesity treatment. BMC Psychiatry 2002, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cortese, S. The Association between ADHD and Obesity: Intriguing, Progressively More Investigated, but Still Puzzling. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dubnov-Raz, G.; Perry, A.; Berger, I. Body mass index of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Child Neurol. 2011, 26, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, S.; Tessari, L. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Obesity: Update 2016. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cortese, S.; Moreira-Maia, C.R.; St. Fleur, D.; Morcillo-Peñalver, C.; Rohde, L.A.; Faraone, S.V. Association Between ADHD and Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, J.T.; Johnstone, J.M.; Musser, E.D.; Long, H.G.; Willoughby, M.T.; Shannon, J. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and being overweight/obesity: New data and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 43, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seymour, K.E.; Reinblatt, S.P.; Benson, L.; Carnell, S.; Sciences, B. Overlapping neurobehavioral circuits in ADHD, obesity, and binge eating: Evidence from Neuroimaging Research. CNS Spectr. 2016, 20, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanc, T.; Cortese, S. Attention deficit/hyperactivity-disorder and obesity: A review and model of current hypotheses explaining their comorbidity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 92, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, J.A.; Phillips, L.N.; Hughes, S.M.; Corson, K. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptomatology, binge eating disorder symptomatology, and body mass index among college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egbert, A.H.; Wilfley, D.E.; Eddy, K.T.; Boutelle, K.N.; Zucker, N.; Peterson, C.B.; Celio Doyle, A.; Le Grange, D.; Goldschmidt, A.B. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms Are Associated with Overeating with and without Loss of Control in Youth with Overweight/Obesity. Child. Obes. 2018, 14, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Veen, M.M.; Kooij, J.J.S.; Boonstra, A.M.; Gordijn, M.C.M.; Van Someren, E.J.W. Delayed Circadian Rhythm in Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Chronic Sleep-Onset Insomnia. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, S.W.N.; Bijlenga, D.; Tanke, M.; Bron, T.I.; van der Heijden, K.B.; Swaab, H.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Sandra Kooij, J.J. Circadian rhythm disruption as a link between Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and obesity? J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 79, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalife, N.; Kantomaa, M.; Glover, V.; Tammelin, T.; Laitinen, J.; Ebeling, H.; Hurtig, T.; Jarvelin, M.-R.; Rodriguez, A. Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms Are Risk Factors for Obesity and Physical Inactivity in Adolescence. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 53, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cook, B.G.; Li, D.; Heinrich, K.M. Obesity, Physical Activity, and Sedentary Behavior of Youth With Learning Disabilities and ADHD. J. Learn. Disabil. 2015, 48, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, S.; Castellanos, F.X. The relationship between ADHD and obesity: Implications for therapy. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2014, 14, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, L.D.; Fleming, J.P.; Klar, D. Treatment of refractory obesity in severely obese adults following management of newly diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verbeken, S.; Braet, C.; Goossens, L.; van der Oord, S. Executive function training with game elements for obese children: A novel treatment to enhance self-regulatory abilities for weight-control. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akiskal, K.K.; Akiskal, H.S. The theoretical underpinnings of affective temperaments: Implications for evolutionary foundations of bipolar disorder and human nature. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 85, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovai, L.; Maremmani, A.G.I.; Rugani, F.; Bacciardi, S.; Pacini, M.; Dell’osso, L.; Akiskal, H.S.; Maremmani, I. Do Akiskal & Mallya’s affective temperaments belong to the domain of pathology or to that of normality? Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 17, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cloninger, C.R.; Svrakic, D.M.; Przybeck, T.R. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1993, 50, 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perugi, G.; Maremmani, I.; Toni, C.; Madaro, D.; Mata, B.; Akiskal, H.S. The contrasting influence of depressive and hyperthymic temperaments on psychometrically derived manic subtypes. Psychiatry Res. 2001, 101, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiskal, H.S.; Hantouche, E.G.; Allilaire, J.F. Bipolar II with and without cyclothymic temperament: “dark” and “sunny” expressions of soft bipolarity. J. Affect. Disord. 2003, 73, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, H.; Tebeka, S.; Girod, C.; Lloret-Linares, C.; Meheust, J.; Scott, J.; Guillaume, S.; Courtet, P.; Bellivier, F.; Delavest, M. Binge eating behaviours in bipolar disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 225, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alciati, A.; D’Ambrosio, A.; Foschi, D.; Corsi, F.; Mellado, C.; Angst, J. Bipolar spectrum disorders in severely obese patients seeking surgical treatment. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 101, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amianto, F.; Lavagnino, L.; Leombruni, P.; Gastaldi, F.; Daga, G.A.; Fassino, S. Hypomania across the binge eating spectrum. A study on hypomanic symptoms in full criteria and sub-threshold binge eating subjects. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 133, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signoretta, S.; Maremmani, I.; Liguori, A.; Perugi, G.; Akiskal, H.S. Affective temperament traits measured by TEMPS-I and emotional-behavioral problems in clinically-well children, adolescents, and young adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 85, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugi, G.; Toni, C.; Passino, M.C.S.; Akiskal, K.K.; Kaprinis, S.; Akiskal, H.S. Bulimia nervosa in atypical depression: The mediating role of cyclothymic temperament. J. Affect. Disord. 2006, 92, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, B.; Mergl, R.; Torrent, C.; Perugi, G.; Padberg, F.; El-Gjamal, N.; Laakmann, G. Abnormal temperament in patients with morbid obesity seeking surgical treatment. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 118, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesiewska, N.; Borkowska, A.; Junik, R.; Kamińska, A.; Pulkowska-Ulfig, J.; Tretyn, A.; Bieliński, M. The Association Between Affective Temperament Traits and Dopamine Genes in Obese Population. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramacciotti, C.E.; Paoli, R.A.; Ciapparelli, A.; Marcacci, G.; Placidi, G.E.; Dell’Osso, L.; Garfinkel, P.E. Affective temperament in the eating disorders. Eat. Weight Disord. 2004, 9, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzola, E.; Fassino, S.; Amianto, F.; Abbate-Daga, G. Affective temperaments in anorexia nervosa: The relevance of depressive and anxious traits. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 218, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feki, I.; Sellami, R.; Chouayakh, S. Eating Disorders and Cyclothymic Temperament: A Cross-Sectional Study on Tunisian Students. Bipolar Disord. Open Access 2016, 2, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N.P.; Miyake, A. Unity and diversity of executive functions: Individual differences as a window on cognitive structure. Cortex 2017, 86, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Favieri, F.; Forte, G.; Casagrande, M. The executive functions in overweight and obesity: A systematic review of neuropsychological cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, J.; Hay, P.; Tchanturia, K.; Smith, E. A randomised controlled trial of manualized cognitive remediation therapy in adult obesity. Appetite 2018, 123, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allom, V.; Mullan, B.; Smith, E.; Hay, P.; Raman, J. Breaking bad habits by improving executive function in individuals with obesity. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Garcia, S.; Miller, L.A.; Strain, G.; Devlin, M.; Wing, R.; Cohen, R.; Paul, R.; Crosby, R.; Mitchell, J.E.; et al. Cognitive function predicts weight loss after bariatric surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2013, 9, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dassen, F.C.M.; Houben, K.; Allom, V.; Jansen, A. Self-regulation and obesity: The role of executive function and delay discounting in the prediction of weight loss. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 41, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reinelt, T.; Petermann, F.; Bauer, F.; Bauer, C.P. Emotion regulation strategies predict weight loss during an inpatient obesity treatment for adolescents. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2020, 6, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Egmond-Fröhlich, A.W.A.; Weghuber, D.; de Zwaan, M. Association of Symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder with Physical Activity, Media Time, and Food Intake in Children and Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Veronese, N.; Facchini, S.; Stubbs, B.; Luchini, C.; Solmi, M.; Manzato, E.; Sergi, G.; Maggi, S.; Cosco, T.; Fontana, L. Weight loss is associated with improvements in cognitive function among overweight and obese people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 72, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunstad, J.; Strain, G.; Devlin, M.J.; Wing, R.; Cohen, R.A.; Paul, R.H.; Crosby, R.D.; Mitchell, J.E. Improved memory function 12 weeks after bariatric surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2011, 7, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vantieghem, S.; Bautmans, I.; De Guchtenaere, A.; Tanghe, A.; Provyn, S. Improved cognitive functioning in obese adolescents after a 30-week inpatient weight loss program. Pediatr. Res. 2018, 84, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, F.G.; Barratt, E.S.; Dougherty, D.M.; Schmitz, J.M.; Swann, A.C. Psychiatric Aspects of Impulsivity. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1783–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, J.A.; Gluck, M.E.; Geliebter, A. Impulsivity and test meal intake in obese binge eating women. Appetite 2004, 43, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregi, A.; Kessler, K.; Hassel, S. Linking cognitive measures of response inhibition and reward sensitivity to trait impulsivity. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénard, M.; Camilleri, G.M.; Etilé, F.; Méjean, C.; Bellisle, F.; Reach, G.; Hercberg, S.; Péneau, S. Association between Impulsivity and Weight Status in a General Population. Nutrients 2017, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giel, K.E.; Teufel, M.; Junne, F.; Zipfel, S.; Schag, K. Food-Related Impulsivity in Obesity and Binge Eating Disorder-A Systematic Update of the Evidence. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meule, A. Impulsivity and overeating: A closer look at the subscales of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X.; Xu, W.; Chen, H. Overweight adults are more impulsive than normal weight adults: Evidence from ERPs during a chocolate-related delayed discounting task. Neuropsychologia 2019, 133, 107181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, R.; Morys, F.; Horstmann, A.; Castiello, U.; Begliomini, C. The impulsive brain: Neural underpinnings of binge eating behavior in normal-weight adults. Appetite 2019, 136, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, J.; Ferreira-Santos, F.; Miller, K.; Torres, S. Emotional processing in obesity: A systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leehr, E.J.; Krohmer, K.; Schag, K.; Dresler, T.; Zipfel, S.; Giel, K.E. Emotion regulation model in binge eating disorder and obesity—A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 49, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittel, R.; Brauhardt, A.; Hilbert, A. Cognitive and emotional functioning in binge-eating disorder: A systematic review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.L.; Abbott, M.J. Processes and pathways to binge eating: Development of an integrated cognitive and behavioural model of binge eating. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McElroy, S.L.; Crow, S.; Blom, T.J.; Cuellar-Barboza, A.B.; Prieto, M.L.; Veldic, M.; Winham, S.J.; Bobo, W.V.; Geske, J.; Seymour, L.R.; et al. Clinical features of bipolar spectrum with binge eating behaviour. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 201, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhardt, A.N.; Corbin, W.R.; Brownell, K.D. Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite 2009, 52, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burrows, T.; Skinner, J.; McKenna, R.; Rollo, M. Food Addiction, Binge Eating Disorder, and Obesity: Is There a Relationship? Behav. Sci. 2017, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gordon, E.L.; Ariel-Donges, A.H.; Bauman, V.; Merlo, L.J. What Is the Evidence for “Food Addiction?” A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ziauddeen, H.; Fletcher, P.C. Is food addiction a valid and useful concept? Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedram, P.; Wadden, D.; Amini, P.; Gulliver, W.; Randell, E.; Cahill, F.; Vasdev, S.; Goodridge, A.; Carter, J.; Zhai, G.; et al. Food Addiction: Its Prevalence and Significant Association with Obesity in the General Population. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meule, A.; Muller, A.; Gearhardt, A.N.; Blechert, J. German version of the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0: Prevalence and correlates of “food addiction” in students and obese individuals. Appetite 2017, 115, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pursey, K.M.; Stanwell, P.; Gearhardt, A.N.; Collins, C.E.; Burrows, T.L. The prevalence of food addiction as assessed by the Yale Food Addiction Scale: A systematic review. Nutrients 2014, 6, 4552–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Imperatori, C.; Innamorati, M.; Contardi, A.; Continisio, M.; Tamburello, S.; Lamis, D.A.; Tamburello, A.; Fabbricatore, M. The association among food addiction, binge eating severity and psychopathology in obese and overweight patients attending low-energy-diet therapy. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1358–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, A.; Leukefeld, C.; Hase, C.; Gruner-Labitzke, K.; Mall, J.W.; Kohler, H.; de Zwaan, M. Food addiction and other addictive behaviours in bariatric surgery candidates. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2018, 26, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, C.; Weiß, A.; Schulte, E.M.; Meule, A.; Ellrott, T. Prevalence of “Food Addiction’’ as Measured with the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 in a Representative German Sample and Its Association with Sex, Age and Weight Categories. Obes. Facts 2017, 10, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperatori, C.; Fabbricatore, M.; Vumbaca, V.; Innamorati, M.; Contardi, A.; Farina, B. Food Addiction: Definition, measurement and prevalence in healthy subjects and in patients with eating disorders. Riv. Psichiatr. 2016, 51, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luigjes, J.; Lorenzetti, V.; de Haan, S.; Youssef, G.J.; Murawski, C.; Sjoerds, Z.; van den Brink, W.; Denys, D.; Fontenelle, L.F.; Yücel, M. Defining Compulsive Behavior. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2019, 29, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gearhardt, A.N.; White, M.A.; Masheb, R.M.; Morgan, P.T.; Crosby, R.D.; Grilo, C.M. An examination of the food addiction construct in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Backman, O.; Stockeld, D.; Rasmussen, F.; Naslund, E.; Marsk, R. Alcohol and substance abuse, depression and suicide attempts after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2016, 103, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, J.E.; Steffen, K.; Engel, S.; King, W.C.; Chen, J.-Y.; Winters, K.; Sogg, S.; Sondag, C.; Kalarchian, M.; Elder, K. Addictive disorders after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2015, 11, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weiss, F.; Barbuti, M.; Carignani, G.; Calderone, A.; Santini, F.; Maremmani, I.; Perugi, G. Psychiatric Aspects of Obesity: A Narrative Review of Pathophysiology and Psychopathology. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082344

Weiss F, Barbuti M, Carignani G, Calderone A, Santini F, Maremmani I, Perugi G. Psychiatric Aspects of Obesity: A Narrative Review of Pathophysiology and Psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(8):2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082344

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeiss, Francesco, Margherita Barbuti, Giulia Carignani, Alba Calderone, Ferruccio Santini, Icro Maremmani, and Giulio Perugi. 2020. "Psychiatric Aspects of Obesity: A Narrative Review of Pathophysiology and Psychopathology" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 8: 2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082344

APA StyleWeiss, F., Barbuti, M., Carignani, G., Calderone, A., Santini, F., Maremmani, I., & Perugi, G. (2020). Psychiatric Aspects of Obesity: A Narrative Review of Pathophysiology and Psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(8), 2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082344