High Effectiveness of a 14-Day Concomitant Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Treatment in Primary Care. An Observational Multicenter Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Statistical Analysis

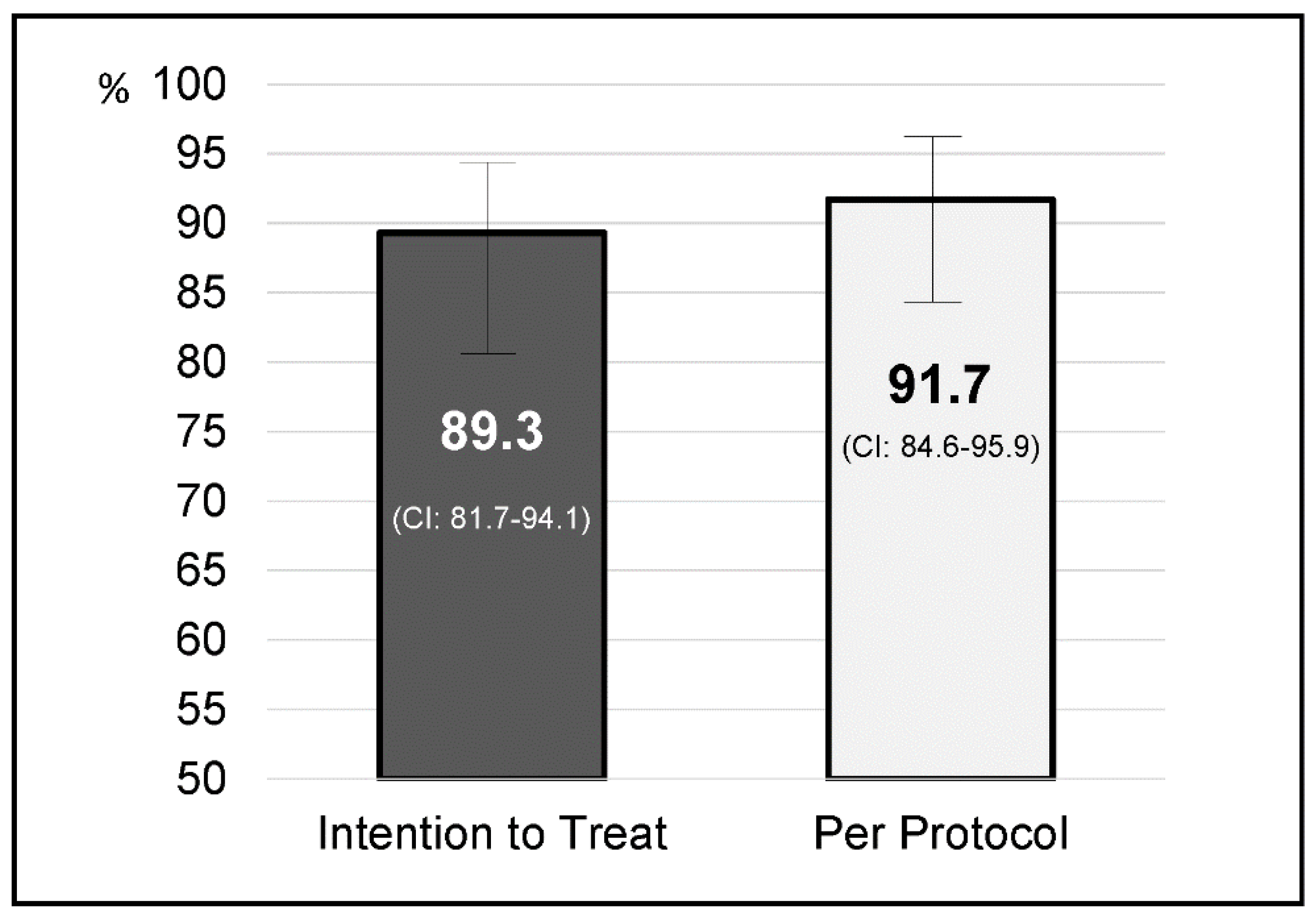

4. Results

Factors Influencing the Efficacy of Therapy

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, B.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, W.-F.; Shi, W.-J.; Liu, W.; Pan, X.-L.; Zhang, G.-X. Efficacy of Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy on Functional Dyspepsia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies with 12-month follow-up. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2014, 48, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, R.; Sarpatwari, A.; Segal, J.B.; Osborn, J.; Evangelista, M.L.; Cooper, N.; Provan, D.; Newland, A.; Amadori, S.; Bussel, J.B. Effects of eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura: A systematic review. Blood 2009, 113, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, S.; Karkhah, A.; Darvish, H.; Validi, M.; Ebrahimpour, S.; Nouri, H.R. Influence of Helicobacter pylori virulence factors CagA and VacA on pathogenesis of gastrointestinal disorders. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 117, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusters, J.G.; Van Vliet, A.H.; Kuipers, E.J. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 449–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Calvet, X. Dealing with uncertainty in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2018, 9, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marshall, B.J. Treatment strategies for Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 1993, 22, 183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Megraud, F.; O’Morain, C.A.; Bazzoli, F.; El-Omar, E.; Graham, D.; Hunt, R.; Rokkas, T.; Vakil, N.; Kuipers, E.J. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—The Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut 2007, 56, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, E.R.; Anderson, G.L.; Morgan, D.R.; Torres, J.; Chey, W.D.; Bravo, L.E.; Dominguez, R.L.; Ferreccio, C.; Herrero, R.; Lazcano-Ponce, E.C.; et al. 14-day triple, 5-day concomitant, and 10-day sequential therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection in seven Latin American sites: A randomised trial. Lancet 2011, 378, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graham, D.Y.; Fischbach, L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut 2010, 59, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, J.; Fang, Y.-J.; Chen, C.-C.; Bair, M.-J.; Chang, C.-Y.; Lee, Y.; Chen, M.-J.; Chen, C.-C.; Tseng, C.; Hsu, Y.-C.; et al. Concomitant, bismuth quadruple, and 14-day triple therapy in the first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori: A multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet 2016, 388, 2355–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Infante, J.; Lucendo, A.J.; Angueira, T.; Rodriguez-Tellez, M.; Pérez-Aisa, A.; Balboa, A.; Barrio, J.; Martín-Noguerol, E.; Gómez-Rodríguez, B.J.; Botargues-Bote, J.M.; et al. Optimised empiric triple and concomitant therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in clinical practice: The OPTRICON study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 41, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Infante, J.; Romano, M.; Fernandez-Bermejo, M.; Federico, A.; Gravina, A.G.; Pozzati, L.; Garcia–Abadia, E.; Vinagre–Rodriguez, G.; Martinez-Alcala, C.; Hernandez-Alonso, M.; et al. Optimized nonbismuth quadruple therapies cure most patients with Helicobacter pylori infection in populations with high rates of antibiotic resistance. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, J.P.; Molina-Infante, J.; Amador, J.; Bermejo, F.; Bujanda, L.; Calvet, X.; Castro-Fernandez, M.; Cuadrado-Lavín, A.; Elizalde, J.I.; Gene, E.; et al. IV Conferencia Española de Consenso sobre el tratamiento de la infección por Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 39, 697–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallone, C.A.; Chiba, N.; van Zanten, S.V.; Fischbach, L.; Gisbert, J.P.; Hunt, R.H.; Jones, N.L.; Render, C.; Leontiadis, G.I.; Moayyedi, P.; et al. The Toronto Consensus for the Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Adults. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Megraud, F.; O’Morain, C.A.; Gisbert, J.P.; Kuipers, E.J.; Axon, A.T.; Bazzoli, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Atherton, J.; Graham, D.Y.; et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut 2017, 66, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chey, W.D.; Leontiadis, G.I.; Howden, C.W.; Moss, S.F. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 212–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, B.-S.; Wu, M.-S.; Chiu, C.-T.; Lo, J.-C.; Wu, D.-C.; Liou, J.-M.; Wu, C.-Y.; Cheng, H.-C.; Lee, Y.; Hsu, P.-I.; et al. Consensus on the clinical management, screening-to-treat, and surveillance of Helicobacter pylori infection to improve gastric cancer control on a nationwide scale. Helicobacter 2017, 22, e12368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, S.M.; Boyle, B.; Brennan, D.; Buckley, M.; Crotty, P.; Doyle, M.; Farrell, R.; Hussey, M.; Kevans, D.; Malfertheiner, P.; et al. The Irish Helicobacter pylori Working Group consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of H. pylori infection in adult patients in Ireland. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 29, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosme, A.; Lizasoan, J.; Montes, M.; Tamayo, E.; Alonso, H.; Mendarte, U.; Martos, M.; Fernández-Reyes, M.; Saraqueta, C.; Bujanda, L. Antimicrobial susceptibility-guided therapy versus empirical concomitant therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori in a region with high rate of clarithromycin resistance. Helicobacter 2015, 21, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholl, A.G.; Marín, A.C.; Molina-Infante, J.; Castro, M.; Barrio, J.; Ducons, J.; Calvet, X.; De La Coba, C.; Montoro, M.; Bory, F.; et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing sequential and concomitant therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication in routine clinical practice. Gut 2013, 63, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, P.; Koumoutsos, I.; Ekmektzoglou, K.; Dogantzis, P.; Vlachou, E.; Kalantzis, C.; Tsibouris, P.; Alexandrakis, G. Concomitant versus sequential therapy for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: A Greek randomized prospective study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 51, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zullo, A.; Scaccianoce, G.; De Francesco, V.; Vannella, L.; Ruggiero, V.; Dambrosio, P.; Castorani, L.; Bonfrate, L.; Hassan, C.; Portincasa, P. Sa1909 Concomitant, Sequential, and Hybrid Therapy for H. pylori Eradication: A Pilot Study. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholl, A.G.; Amador, J.; Ricote, M.; Cañones-Garzón, P.J.; Gene, E.; Calvet, X.; Gisbert, J.P.; Spanish Primary Care Societies SEMFyC, SEMERGEN and SEMG, the Spanish Association of Gastroenterology; OPTICARE Long-Term Educational Project. Spanish primary care survey on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection and dyspepsia: Information, attitudes, and decisions. Helicobacter 2019, 24, e12593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNicholl, A.G.; Molina-Infante, J.; Bermejo, F.; Harb, Y.; Modolell, I.; Anton, R. Non bismuth quadruple “concomitant” therapies in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Standard vs optimized (14 days, high-dose PPI) regimes in clinical practice. Helicobacter 2014, 19 (Suppl. 1), 11. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Total | p | |

| Age—Years—(Mean ± SD) | 46.7 ± 16.1 | 0.921 | |

| Sex | Men | 50 (44.6%) | 0.404 |

| Women | 62 (55.4%) | ||

| Tobacco | Smoker | 16 (14.3%) | 0.404 |

| Non-smoker | 96 (85.7%) | ||

| Primary care centers (PCC) | PCC Bases de Manresa/PCC Barri Antic. Althaia | 21 (18.8%) | 0.369 |

| PCC Granollers | 54 (48.2%) | ||

| PCC Badia Valés | 8 (7.1%) | ||

| PCC Arbúcies/PCC St Hilari. Girona | 29 (25.9%) | ||

| Main indications | Non-investigated dyspepsia | 93 (83%) | 0.127 |

| Functional dyspepsia | 14 (12.5%) | ||

| Peptic ulcer | 4 (3.6%) | ||

| Others | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Diagnostic test previous to treatment | Histology | 5 (4.5%) | 0.624 |

| Urea breath test | 23 (20.5%) | ||

| Helicobacter pylori stool antigen | 75 (67%) | ||

| Rapid Urease Test | 9 (8%) | ||

| Treatment adherence | Complete | 104 (92.9%) | 0.004 |

| Partial | 8 (7.1%) | ||

| Mild side effects | Yes | 47 (42%) | 0.004 |

| No | 65 (58%) | ||

| Diagnostic test post treatment | Helicobacter pylori stool antigen | 96 (85.7%) | 0.633 |

| Urea breath test | 16 (14.3%) | ||

| Variables | Total | p | |

| Age—Years—(Mean ± SD) | 46.7 ± 16.1 | 0.921 | |

| Sex | Men | 50 (44.6%) | 0.404 |

| Women | 62 (55.4%) | ||

| Tobacco | Smoker | 16 (14.3%) | 0.404 |

| Non-smoker | 96 (85.7%) | ||

| Primary care centers (PCC) | PCC Bases de Manresa/PCC Barri Antic. Althaia | 21 (18.8%) | 0.369 |

| PCC Granollers | 54 (48.2%) | ||

| PCC Badia Valés | 8 (7.1%) | ||

| PCC Arbúcies/PCC St Hilari. Girona | 29 (25.9%) | ||

| Main indications | Non-investigated dyspepsia | 93 (83%) | 0.127 |

| Functional dyspepsia | 14 (12.5%) | ||

| Peptic ulcer | 4 (3.6%) | ||

| Others | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Diagnostic test previous to treatment | Histology | 5 (4.5%) | 0.624 |

| Urea breath test | 23 (20.5%) | ||

| Helicobacter pylori stool antigen | 75 (67%) | ||

| Rapid Urease Test | 9 (8%) | ||

| Treatment adherence | Complete | 104 (92.9%) | 0.004 |

| Partial | 8 (7.1%) | ||

| Mild side effects | Yes | 47 (42%) | 0.004 |

| No | 65 (58%) | ||

| Diagnostic test post treatment | Helicobacter pylori stool antigen | 96 (85.7%) | 0.633 |

| Urea breath test | 16 (14.3%) | ||

| Variables | Intention to Treat (95% CI) | Per Protocol (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Men | 92% (80–97.4) | 93.9% (82.2–98.4) |

| Women | 87.1% (75.6–93,4) | 90% (78.8–95.9) | |

| Tobacco | Smoker | 93.8% (67.8–99.7) | 93.8% (67.8–99.7) |

| Non-smoker | 88.5% (80–93.8) | 91.4% (83.3–96) | |

| Primary care centers (PCC) | PCC Bases de Manresa/PCC Barri Antic. Althaia | 85.7% (62.6–96.2) | 85.7% (62.6–96.2) |

| PCC Granollers | 92.6% (81.3–97.6) | 92.6% (81.3–97.6) | |

| PCC Badia Valés | 100% (59.8–98.8) | 100% (59.8–100) | |

| PCC Arbúcies/PCC St Hilari. Girona | 82.8% (63.6–93.5) | 92.3% (73.4–98.7) | |

| Main indications | Non-investigated dyspepsia | 91.4% (83.3–95.9) | 94.4% (83.3–95.9) |

| Functional dyspepsia | 71,4% (42–90.4) | 71,4% (42–90.4) | |

| Peptic ulcer | 100% (39.6–97.6) | 100% (39.6–100) | |

| Others | 100% (5.4–89.2) | 100% (5.4–100) | |

| Diagnostic test previous to treatment | Histology | 80% (29.9–98.9) | 80% (29.9–98.9) |

| Urea breath test | 91.3% (70.5–98.5) | 95.5% (75.2–99.8) | |

| Helicobacter pylori stool antigen | 88% (80–94) | 90.4% (80.1–95.6) | |

| Rapid Urease Test | 100% (62.9–99) | 100% (62.9–100) | |

| Diagnostic test post treatment | Helicobacter pylori stool antigen | 89.7% (81.4–94.7) | 92.6% (84.8–96.7) |

| Urea breath test | 86.7% (58.4–97.7) | 86.7% (58.4–97.7) | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olmedo, L.; Azagra, R.; Aguyé, A.; Pascual, M.; Calvet, X.; Gené, E. High Effectiveness of a 14-Day Concomitant Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Treatment in Primary Care. An Observational Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082410

Olmedo L, Azagra R, Aguyé A, Pascual M, Calvet X, Gené E. High Effectiveness of a 14-Day Concomitant Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Treatment in Primary Care. An Observational Multicenter Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(8):2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082410

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlmedo, Llum, Rafael Azagra, Amada Aguyé, Marta Pascual, Xavier Calvet, and Emili Gené. 2020. "High Effectiveness of a 14-Day Concomitant Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Treatment in Primary Care. An Observational Multicenter Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 8: 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082410

APA StyleOlmedo, L., Azagra, R., Aguyé, A., Pascual, M., Calvet, X., & Gené, E. (2020). High Effectiveness of a 14-Day Concomitant Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Treatment in Primary Care. An Observational Multicenter Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(8), 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082410