Aligning Strategic Objectives with Research and Development Activities in a Soft Commodity Sector: A Technological Plan for Colombian Cocoa Producers

Abstract

1. Introduction

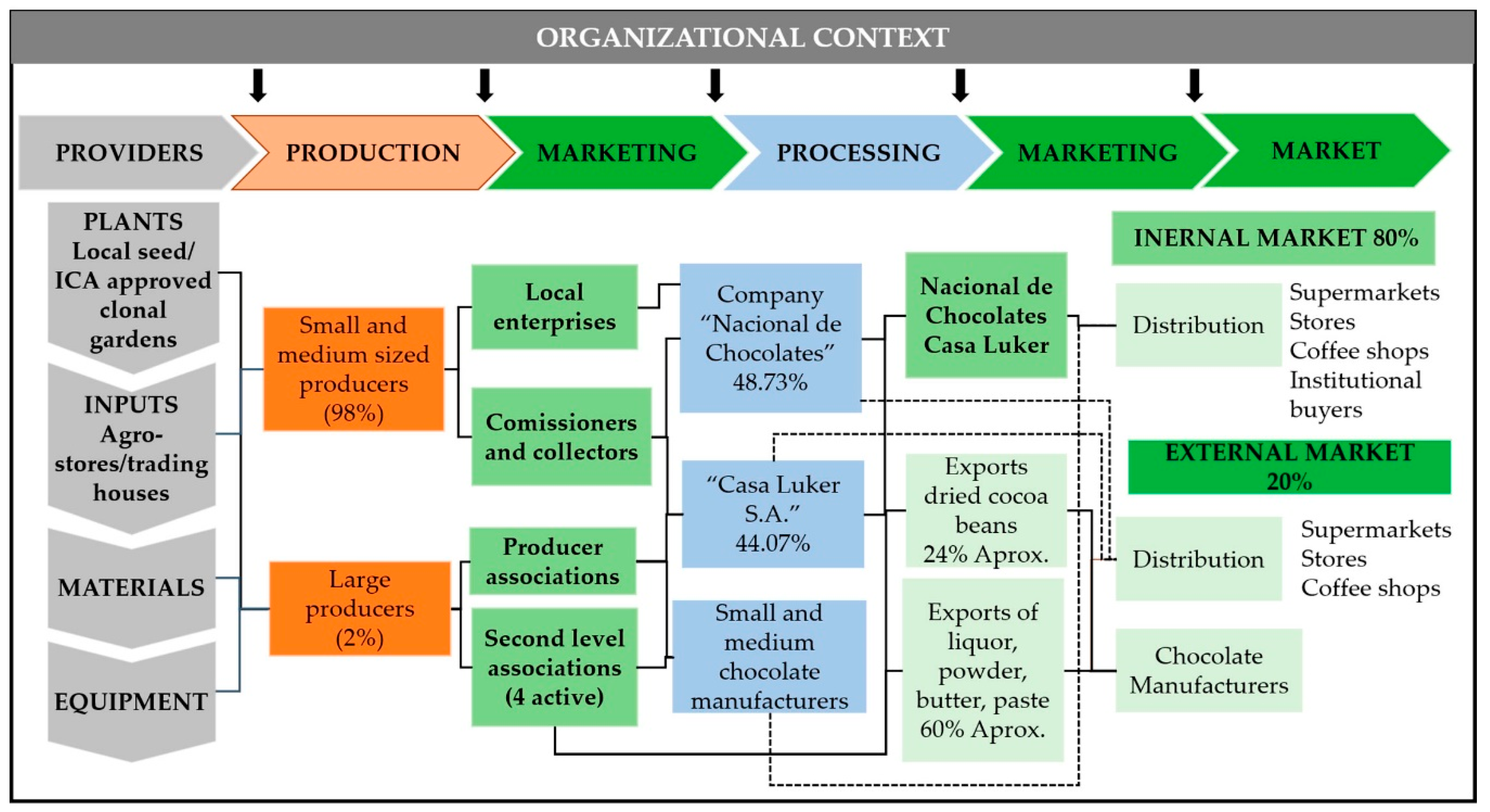

The Colombian Cocoa Sector in Context: Stakeholders and Organizational Structure

2. Methodology for the Empirical Analysis

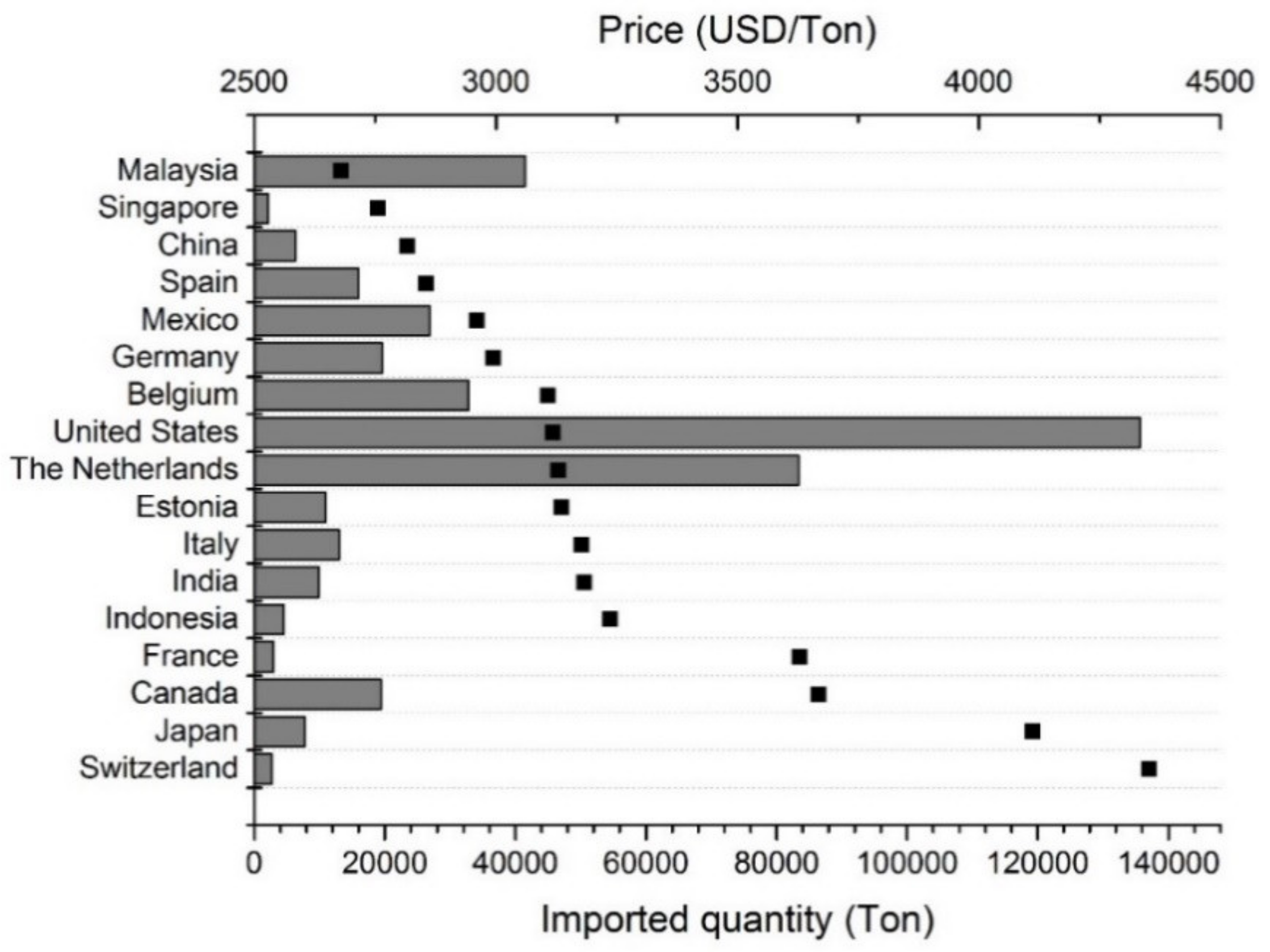

2.1. Phase 1: Market Demands and Opportunities

Market Competitive Intelligence

2.2. Phase 2: Current State of the Producer Segment of the Colombian Cocoa Value Chain

2.2.1. Diagnostic of Constraints and Weaknesses

2.2.2. Construction of Ideal Practices/Scenarios

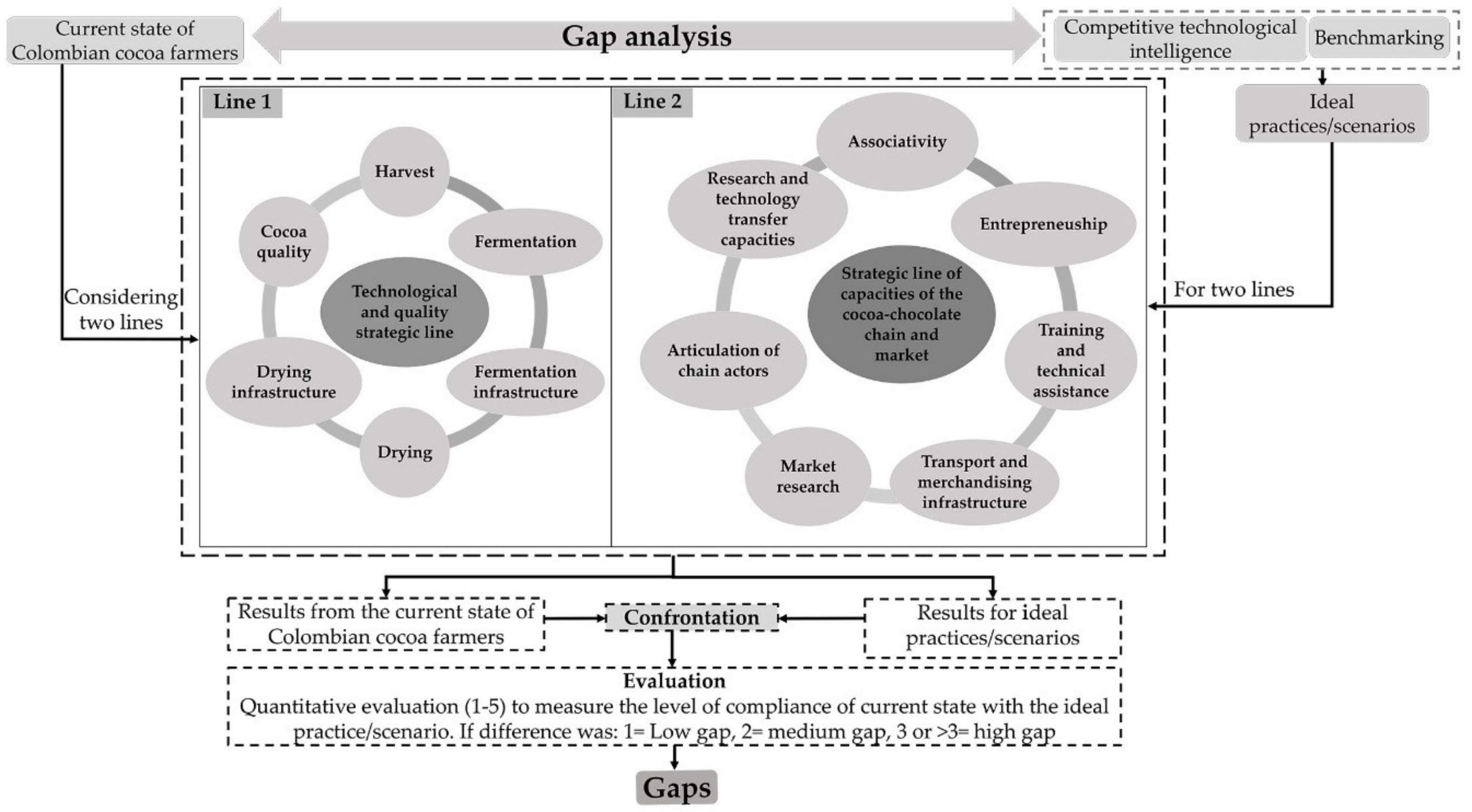

2.2.3. Gap Analysis

2.2.4. Data Sources and Data Collection

2.3. Phase 3: R&D Proposals to Strengthen the Capacities and the Competitiveness of Colombian Cocoa Farmers to Enter Specialty Cocoa Markets

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Market Demands and Opportunities

3.2. Current State and Trends of Vulnerable Links in the Producer Segment of the Colombian Cocoa Value Chain

3.2.1. Technological and Quality Line

Production and Harvest

Preconditioning Operations

Fermentation and Drying

Bean Quality

3.2.2. Strategic Line of Chain Capacities and Market

Associativity

Entrepreneurship

Training and Technical Assistance

Infrastructure and Technological Transfer

3.3. Ideal Practices/Scenarios and Gap Analysis

Gap Analysis

3.4. R&D Proposals to Strengthen the Capacities and Competitiveness of the Colombian Cocoa Sector

3.4.1. Technological and Quality Line

3.4.2. Capacities and Market Line

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Highlights

References

- Smyth, S.; Phillips, P.W.B. Product differentiation alternatives: Identity preservation, segregation, and traceability. AgBioForum 2002, 5, 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, F.; Rehpani, C.; Ruiz, A.; Lecaro, J. Estrategias País Para la Oferta de Cacaos Especiales—Políticas e Iniciativas Privadas Exitosas en el Perú, Ecuador, Colombia y República Dominicana; Swisscontact Colombia Foundation: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kongor, J.E.; Hinneh, M.; de Walle, D.V.; Afoakwa, E.O.; Boeckx, P.; Dewettinck, K. Factors influencing quality variation in cocoa (Theobroma cacao) bean flavour profile—A review. Food Res. Int. 2016, 82, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, P.C.; Benjamin, T.J.; Burniske, G.R.; Croft, M.M.; Fenton, M.C.; Kelly, C.; Lundy, M.; Rodríguez-Camayo, F.; Wilcox, M. Un Análisis de la Cadena Productiva del Cacao en Colombia [An Analysis of the Cocoa Production Chain in Colombia]; USAID Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017.

- Mudambi, R. Location, control and innovation in knowledge-intensive industries. J. Econ. Geogr. 2008, 8, 699–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everatt, D.; Tsai, T.; Cheng, B. The Acer Group’s China Manufacturing Decision, Version A; Ivey Case Series #9A99M009; Richard Ivey School of Business, University of Western Ontario: London, ON, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bair, J.; Gereffi, G. Local Clusters in Global Chains: The Causes and Consequences of Export Dynamism in Torreon’s Blue Jeans Industry. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1885–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamber, P.; Fernandez-Stark, K.; Gereffi, G.; Guinn, A. Connecting Local Producers in Developing Countries to Regional and Global Value Chains. OECD Trade Policy Pap. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, S.; Gereffi, G.; Rossi, A. Economic and social upgrading in global production networks: A new paradigm for a changing world. Int. Labour Rev. 2011, 150, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, O.; Gereffi, G.; Staritz, C. Global Value Chains in a Postcrisis World: A Development Perspective; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-8213-8499-2. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, E.; Pietrobelli, C.; Rabellotti, R. Upgrading in Global Value Chains: Lessons from Latin American Clusters. World Dev. 2005, 33, 549–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G.; Fernandez-Stark, K. Global Value Chain Analysis: A Primer; The Duke Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness (Duke CGGC): Durham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Stark, K.; Bamber, P.; Gereffi, G. Workforce Development in the Fruit and Vegetable Global Value Chain. In Skills for Upgrading: Workforce Development and Global Value Chains in Developing Countries; The Duke Center on Globalization Governance & Competitiveness and RTI International: Durham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J. Firm capabilities and technology ladders: Sequential foreign direct investments of Japanese electronic firms in East Asia. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICCO Fine or Flavour Cocoa. Available online: http://www.icco.org/about-cocoa/fine-or-flavour-cocoa.html (accessed on 14 January 2018).

- Fernandez-Stark, K.; Bamber, P. Basic Principles and Guidelines for Impactful and Sustainable Inclusive Business Interventions in High-Value Agro-Food Value Chains; The Duke Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness (Duke CGGC): Durham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Stark, K.; Bamber, P.; Gereffi, G. Inclusion of Small- and Medium-Sized Producers in High-Value Agro-Food Value Chains; The Duke Center on Globalization Governance & Competitiveness and RTI International: Durham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, A.; Castellanos, O.; Domínguez, K. Mejoramiento de la poscosecha del cacao a partir del roadmapping [Improvement of cocoa post-harvest from roadmapping], Ingeniería e Investigación. Ing. Investig. 2008, 28, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, J.A.; Ríos, L.A. Caracterización de sistemas agroecológicos para el establecimiento de cacao (Theobroma cacao L.), en comunidades afrodescendientes del Pacífico Colombiano (Tumaco–Nariño, Colombia) [Characterization of agroecological systems for the establishment of cacao]. Acta Agronómica 2015, 65, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, J.A. Características Estructurales y Funcionales de un Faro Agroecológico a Partir de las Experiencias de Productores Cacaoteros de las Regiones de los Departamentos de Nariño, Meta, Caquetá y Tolima’; Structural and Functional Characteristics of an Agroecolog; Antioquia University: Medellín, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Santander, M.; Rodríguez, J.; Vaillant, F.; Escobar, S. An overview of the physical and biochemical transformation of cocoa seeds to beans and to chocolate: Flavor formation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jano, P.; Mainville, D. The Cacao Marketing Chain in Ecuador: Analysis of Chain Constraints to the Development of Markets for High-Quality Cacao. In Proceedings of the International Food and Agribusiness Management Association (IAMA), Parma, Italy, 23–26 June 2007; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Geum, Y. Development of the scenario-based technology roadmap considering layer heterogeneity: An approach using CIA and AHP. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 117, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.M.; Fleury, A.; Lopes, A.P. An overview of the literature on technology roadmapping (TRM): Contributions and trends. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2013, 80, 1418–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willyard, C.M.; McCless, C.W. Motorola’s technology roadmap process. Res. Manag. 1987, 30, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, M.; Amaral, D. Roadmapping for technology push and partnership: A contribution for open innovation environments. Technovation 2011, 31, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Song, B.; Park, Y. An instrument for scenario based technology roadmapping: How to assess the impacts of future changes on organizational plans. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2015, 90, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.; Grebeniuk, A.; Meissner, D. Smart roadmapping for STI policy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 110, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.Y.; O’Sullivan, E. Strategic standardisation of smart systems: A roadmapping process in support of innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 115, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulsamad, A.; Frederick, S.; Guinn, A.; Gereffi, G. Pro-Poor Development and Power Asymmetries in Global Value Chains; The Duke Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness: Durham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, L. El consumo de Chocolate como Experiencia Comunicativa del Afecto y el Vínculo Social en Bogotá; Pontificia Universidad Javeriana: Bogotá, Colombia, 2016; Volume 53. [Google Scholar]

- Colciencias; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development; Corpoica. Plan Estratégico de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación del Sector Agroindustrial: 2017–2020 [Strategic Plan for Science, Technology and Innovation of the Agroindustrial Sector: 2017–2020]; Corpoica: Bogotá, Colombia, 2016.

- International Cocoa Organization—ICCO. Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics, Volume XLII No. 4 Cocoa Year 2015/16; ICCO: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Cocoa Organization—ICCO. Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics, Cocoa Year 2016/17; ICCO: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2016; Volume XLIII. [Google Scholar]

- International Cocoa Organization—ICCO. Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics, Volume XLV-No-2 Cocoa Year 2017/18; ICCO: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Cocoa Organization—ICCO. Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics QBSC Volume XLV-No-2 Cocoa Year 2018/19; ICCO: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trademap Trade Statistics for International Business Development. Available online: http://www.trademap.com (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- Saritas, O.; Aylen, J. Using scenarios for roadmapping: The case of clean production. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2010, 77, 1061–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bildosola, I.; Río-Bélver, R.M.; Garechana, G.; Cilleruelo, E. TeknoRoadmap, an approach for depicting emerging technologies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 117, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probert, D.R.; Farrukh, C.J.P.; Phaal, R. Technology roadmapping—Developing a practical approach for linking resources to strategic goals. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2003, 217, 1183–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicex Procolombia Information Center. Available online: http://www.sicex.com (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- Guehi, T.S.; Zahouli, I.B.; Ban-Koffi, L.; Fae, M.A.; Nemlin, J.G. Performance of different drying methods and their effects on the chemical quality attributes of raw cocoa material. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 1564–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltini, R.; Akkerman, R.; Frosch, S. Optimizing chocolate production through traceability: A review of the influence of farming practices on cocoa bean quality. Food Control 2013, 29, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escorsa, P.; Maspons, R. De la Vigilancia Tecnológica a la Inteligencia Competitiva [From Technological Surveillance to Competitive Intelligence]; Prentice Hall: Madrid, España, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, C. Analysis of the Cocoa Value Chain in Colombia: Generation of Technological Strategies in Harvest and Post-Harvest, Organizational, Installed Capacity and Market Operations; Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Loader, R.; Amartya, L. Participatory Rural Appraisal: Extending the research methods base. Agr. Syst. 1999, 62, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, M.S.; Ahmad, S.; Jan, K.; Bashir, K. Status, supply chain and processing of cocoa—A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 66, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markets and Markets. Cocoa & Chocolate Market by application (Confectionery, Food & Beverage), Cocoa Type (Butter, Powder, & Liquor), Chocolate Type (Dark, White, Milk)—Global Trends & Forecasts to 2019. Available online: http://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/cocoa-chocolate-market-226179290.html (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- Useche, P.; Blare, T. Traditional vs. modern production systems: Price and nonmarket considerations of cacao producers in Northern Ecuador. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 93, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blare, T.; Useche, P. Competing objectives of smallholder producers in developing countries: Examining cacao production in Northern Ecuador. Environ. Econ. 2013, 4, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ardila, C.; Cortés, M.; Rodríguez, D.; Mura, I.; Medaglia, A.; Rodríguez, J.; Escobar, S. Cocoa Processing and Commercialization: Processing Plant Feasibility Study through the Use of Operation Research Techniques; Universidad de los Andes: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- CBI–Centre for the Promotion of Imports from Developing Countries Exporting Certified Cocoa to Europe. Available online: https://www.cbi.eu/market-information/cocoa/certified-cocoa/ (accessed on 25 February 2018).

- ICCO-International Cocoa Organization Study on the Costs, Advantages and Disadvantages of Cocoa Certification. Available online: https://www.icco.org/about-us/international-cocoa-agreements/cat_view/30-related-documents/37-fair-trade-organic-cocoa.html (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- SSI The State of Sustainability Initiatives Review 2014: Standards and the Green Economy. Available online: http://www.iisd.org/pdf/2014/ssi_2014_chapter_7.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Copetti, M.V.; Iamanaka, B.T.; Pitt, J.I.; Taniwaki, M.H. Fungi and mycotoxins in cocoa: From farm to chocolate. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 178, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ochoa, F.; Gomez, E.; Santos, V.E.; Merchuk, J.C. Oxygen uptake rate in microbial processes: An overview. Biochem. Eng. J. 2010, 49, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, S.; Rodriguez, A.; Gomez, E.; Alcon, A.; Santos, V.E.; Garcia-Ochoa, F. Influence of oxygen transfer on Pseudomonas putida effects on growth rate and biodesulfurization capacity. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 39, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cáceres, R.G.; Perdomo, A.; Ortiz, O.; Beltrán, P.; López, K. Characterization of the supply and value chains of Colombian cocoa. Dyna 2014, 81, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panlibuton, H.; Lusby, F. Indonesia Cocoa Bean Value Chain Case Study; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2006.

- Castellanos Domínguez, O.F.; Torres Piñeros, L.M.; Fonseca Rodríguez, S.L.; Montañez, F.V.M.; Sánchez, A. Agenda Prospectiva de Investigación y Desarrollo Tecnológico Para la Cadena Productiva de Cacao-Chocolate en Colombia [Prospective Research and Technological Development Agenda for the Cocoa-Chocolate Production Chain in Colombia]; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development: Bogotá, Colombia, 2007; ISBN 9789589712832.

- Asamoah, D.; Annan, J. Analysis of Ghana’s cocoa value chain towards services and standards for stakeholders. Int. J. Serv. Stand. 2012, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan, M.B.; Fromm, I.; Aidoo, R. From Producers to Export Markets: The Case of the Cocoa Value Chain in Ghana. J. African Dev. 2013, 15, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzimah, S.K.; Asiam, E.K. Design of a cocoa pod splitting machine. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2010, 2, 622–634. [Google Scholar]

- Bernaert, H.; Camu, N.; Lohmueller, T. Method for Processing Cocoa Beans. U.S. Patent 20110123675A1, 26 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G.V.; Magalhães, K.T.; de Almeida, E.G.; da Silva Coelho, I.; Schwan, R.F. Spontaneous cocoa bean fermentation carried out in a novel-design stainless steel tank: Influence on the dynamics of microbial populations and physical-chemical properties. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 161, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayavenkataraman, S.; Iniyan, S.; Goic, R. A review of solar drying technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 2652–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crafack, M.; Keul, H.; Eskildsen, C.E.; Petersen, M.A.; Saerens, S.; Blennow, A.; Skovmand-Larsen, M.; Swiegers, J.H.; Petersen, G.B.; Heimdal, H.; et al. Impact of starter cultures and fermentation techniques on the volatile aroma and sensory profile of chocolate. Food Res. Int. 2014, 63, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwan, R.F.; Wheals, A.E. The microbiology of cocoa fermentation and its role in chocolate quality. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2004, 44, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brito, E.S.; Garcia, N.H.P.; Amancio, A.C. Use of a proteolytic enzyme in cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) processing. Brazilian Arch. Biol. Technol. 2004, 47, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afoakwa, E.O.; Paterson, A.; Fowler, M.; Ryan, A. Flavor formation and character in cocoa and chocolate: A critical review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 840–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owusu, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Heimdal, H. Effect of fermentation method, roasting and conching conditions on the aroma volatiles of dark chocolate. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2012, 36, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afoakwa, E.O.; Kongor, J.E.; Budu, A.S.; Mensah-Brown, H.; Takrama, J.F. Changes in Biochemical and Physico-chemical Qualities during Drying of Pulp Preconditioned and Fermented Cocoa (Theobroma cacao) Beans. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2015, 15, 9651–9670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afoakwa, E.O.; Quao, J.; Takrama, J.; Budu, A.S.; Saalia, F.K. Chemical composition and physical quality characteristics of Ghanaian cocoa beans as affected by pulp pre-conditioning and fermentation. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, W.A.; Böttcher, N.L.; Aßkamp, M.; Bergounhou, A.; Kumari, N.; Ho, P.; D’Souza, R.N.; Nevoigt, E.; Ullrich, M.S. Forcing fermentation: Profiling proteins, peptides and polyphenols in lab-scale cocoa bean fermentation. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayeulle, N.; Meudec, E.; Boulet, J.C.; Vallverdu-Queralt, A.; Hue, C.; Boulanger, R.; Cheynier, V.; Sommerer, N. Fast Discrimination of Chocolate Quality Based on Average-Mass-Spectra Fingerprints of Cocoa Polyphenols. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 2723–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, C.O.; Bispo, E.D.; de Santana, L.R.R.; de Carvalho, R.D.S. Use of “Cocoa honey” (Theobroma cacao L.) for diet jelly preparation: An alternative technology. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2014, 36, 640–648. [Google Scholar]

- Schwan, R.; Fleet, G. Cocoa and Coffee Fermetation; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781439847930. [Google Scholar]

- Vriesmann, L.C.; Castanho Amboni, R.D.; De Oliveira Petkowicz, C.L. Cacao pod husks (Theobroma cacao L.): Composition and hot-water-soluble pectins. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 34, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Guarín, J.A.; Berdugo-Cely, J.; Coronado, R.A.; Zapata, Y.P.; Quintero, C.; Gallego-Sánchez, G.; Yockteng, R. Colombia a Source of Cacao Genetic Diversity As Revealed by the Population Structure Analysis of Germplasm Bank of Theobroma cacao L. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamayor, J.C.; Lachenaud, P.; da Silva e Mota, J.W.; Loor, R.; Kuhn, D.N.; Brown, J.S.; Schnell, R.J. Geographic and genetic population differentiation of the Amazonian chocolate tree (Theobroma cacao L.). PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajalahti, R.; Janssen, W.; Pehu, E. Agricultural Innovation Systems: From Diagnostics toward Operational Practices; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Umali-Deininger, D. Linking Farmers to the Market. Dev. Outreach 2008, 10, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castella, J.C.; Bounthanom, B. Farmer cooperatives are the missing link to meet market demands in Laos. Dev. Pract. 2014, 24, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R. New Roles of the Public Sector for an Agriculture for Development Agenda; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, G.A.; Corredoira, R.A.; Kruse, G. Public-Private Institutions as Catalysts of Upgrading in Emerging Market Societies. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 1270–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen-Smith, J.; Powell, W.W. Knowledge networks as channels and conduits: The effects of spillovers in the Boston biotechnology community. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, E.; Sgourev, S. Peer capitalism: Parallel relationships in the U.S. economy. Am. J. Sociol. 2006, 111, 1327–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirwa, E.; Dorward, A.; Kachule, R.; Kumwenda, I.; Kydd, J.; Poole, N.; Poulton, C.; Stockbridge, M. Farmer Organisations for Market Access: Principles for Policy and Practice; United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID): London, UK, 2005.

- Reveley, J.; Ville, S. Enhancing Industry Association Theory: A Comparative Business History Contribution. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 837–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, N.; Freece, A. A Review of Existing Organisational Forms of Smallholder Farmers’ Associations and Their Contractual Relationships with Other Market Participants in the East and Southern African ACP Region; FAO: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bingen, J.; Serrano, A.; Howard, J. Linking farmers to markets: Different approaches to human capital development. Food Policy 2003, 28, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornchulee, N. The role of agricultural leaders in farmer associations and the implications to agricultural extension education in Thailand; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, X.; Lambin, E. Linking Globalization to Local Land Uses: How Eco-Consumers and Gourmands are Changing the Colombian Coffee Landscapes. World Dev. 2013, 41, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudambi, R.; Paul, C. Domestic drug prohibition as a source of foreign institutional instability: An analysis of the multinational extralegal enterprise. J. Int. Manag. 2003, 9, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

The implementation of these projects considers participatory innovation and transfer plans and the ex-ante, during, and ex-post impact evaluation of the projects in both lines.

The implementation of these projects considers participatory innovation and transfer plans and the ex-ante, during, and ex-post impact evaluation of the projects in both lines.

The implementation of these projects considers participatory innovation and transfer plans and the ex-ante, during, and ex-post impact evaluation of the projects in both lines.

The implementation of these projects considers participatory innovation and transfer plans and the ex-ante, during, and ex-post impact evaluation of the projects in both lines.

| Operations and Postharvest Variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed Preconditioning (Storage Days) | Fermentation | Drying | |||||

| Cluster or Postharvest Practice | Number of Farmers Using the Practice | Fermentation Time (Days) | Duration of Anaerobic Phase (Hours) | Duration of Aerobic Phase (Hours) | Aeration Frequency (Intervals in Hours) | Initial Solar Exposure Time (Hours) | |

| 1 | 49 | 3 | 6 | 34 | 109 | 24 | 9 |

| 2 | 40 | 0 | 6 | 37 | 107 | 24 | 9 |

| 3 | 29 | 2 | 4 | 30 | 60 | 24 | 9 |

| 4 | 45 | 2,5 | 6 | 42 | 101 | 30 | 4 |

| 5 | 49 | 2 | 5 | 57 | 72 | 43 | 9 |

| 6 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 52 | 92 | 32 | 9 |

| Number of Cocoa Farmers | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster or Posharvest Practice * | Antioquia | Arauca | Cesar | Huila | Nariño | Santander | Boyacá | Cundinamarca | Tolima | Norte de Santander |

| 1 | 13% | 32% | 20% | 38% | 50% | 25% | 7% | 23% | 30% | 33% |

| 2 | 41% | 9% | 47% | 31% | 0% | 3% | 17% | 8% | 13% | 6% |

| 3 | 13% | 0% | 13% | 15% | 0% | 6% | 13% | 8% | 35% | 22% |

| 4 | 0% | 45% | 0% | 15% | 0% | 47% | 11% | 62% | 22% | 0% |

| 5 | 31% | 9% | 20% | 0% | 50% | 16% | 41% | 0% | 0% | 39% |

| 6 | 3% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 11% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Technological and Quality Strategic Line | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvest | Fermentation | Fermentation Infrastructure | Drying | Drying Infrastructure | Cocoa Quality |

| 1. Carrying out sanitary classification of pods, separating diseased fruits from healthy ones. | 1. Measuring process variables as temperature, pH, and degree of fermentation. | 1. The fermentation system adjusts to different quantities of fresh cocoa mass. | 1. Mixing frequently the cocoa beans in the drying bed. | 1. Separating dirt from cocoa beans. | |

| 2. Harvesting only ripe pods. | 2. Application of a final quality test to determine the degree of fermentation. | 2. The fermentation system is designed considering ergonomic parameters for handling. | 2. Carrying out quality tests on the cocoa beans at the end of process. | 2. Classifying the cocoa beans by physical quality parameters. | |

| 3. Harvesting with appropriate tools and techniques that do not damage flower cushions and trees. | 3. Using the minimum required quantity of cocoa mass to obtain a suitable degree of fermentation. | 3. The fermentation system is made of suitable materials to carry out the bioprocess (new materials could replace wood). | 3. Employing instrumental measuring equipment to carry out quality tests on cocoa beans. | 1. The drying system has a surface made of suitable material for food drying. | 3. Knowing the sensory profile of the cocoa produced. |

| 4. Harvesting specific genotypes independently. | 4. Independent transformation of cocoa varieties according to their particular characteristics. | 4. Farmers measure environmental variables in which fermentation systems are located. | 4. Design and manage the drying process according to the desired characteristics of the final product. | 2. The drying system is designed taking into account engineering and operating parameters. | 4. Implementing a traceability record of the cocoa produced. |

| 5. Knowing and applying a preconditioning operation of pods and/or cocoa seeds before fermentation. | 5. Using starter cultures or chemical compounds and enzymes to improve the quality in the final product. | 5. The fermentation system is isolated from the environment, and it is located in a place with adequate ventilation. | 5. Control of solar radiation times for cocoa beans. | 5. Implementing good manufacturing practices. | |

| 6. Establishment of process protocols in function of process variables (chemical molecule precursors that generate flavor in chocolate) related to the quality of the product to be generated. | 6. The fermentation system allows the adequate drainage of the sweatings generated by the process. | 6. Measuring process variables (temperature, moisture, and drying rate). | |||

| Strategic Line of Capacities of the Cocoa-Chocolate Value Chain and Market | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Associativity | Entrepreneurial Vision of Cocoa Cultivation | Training and Technical Assistance | Transport and Merchandising Infrastructure | Market Research | Articulation of Chain Actors | Research and Technology Transfer Capacities |

| 1. Suitable communication infrastructure in rural zones that allows product transport to buying centers. | 1. Articulated work of different actors: public entities as local and departmental governments: universities and research institutes; private sector: NGOs and financial entities for the competitiveness of the chain aligned under a strategic plan (collaborative projects and joint actions). | |||||

| 1. Presence and operation of community postharvest centers and evaluation of their profitability/sustainability. | 1. Strategic training plans and technical assistance. | 2. Suitable places to store and market cocoa taking into account food-handling regulations. | 1. Human resources trained in areas that contribute to the competitiveness of each value chain link. | |||

| 1. Presence of first- and second-level consolidated farmers’ associations that operate efficiently. | 2. Presence of productive units or associations where the cocoa bean is transformed in an artisanal way or even with a low level of agroindustrialization. | 2. Sufficient coverage for the farmers of the region. | 3. Implementation of the Colombian technical standard: NTC1252. | 2. Infrastructure for research and technology transfer. | ||

| 2. Certification processes of production units led by associations. | 3. Initiatives and capabilities for the generation of cocoa added-value products and capacity to develop market and product innovations. | 3. Relevance of public institutions for training and technical assistance. | 4. Access and/or establishment of own quality control laboratories. | 1. Performing market studies that guide the business prospects in the region. | 3. Coordination of research, training, and educational programs targeting main sectorial demands. | |

| 3. Equitable resource management and benefit transfer to association members. | 4. Associations with experience in cocoa bean export to international clients. | 4. Participation of the private sector or Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs) in the training and technical assistance processes. | 5. Direct sale channels. | 2. Developing and updating continuously national and international market variables that guide producer’s decisions, such as prices, quantities traded, national available supply for different types of cocoa, etc. | 4. Research and transfer projects. | |

| 5. Presence of cocoa companies. | 5. Farmer leaders who act as transference agents of good cocoa practices. | 6. Differentiation of prices by quality. | 5. Information systems for knowledge transfer. | |||

| 6. Suppliers of appropriate and certified inputs for the cultivation of cocoa, including plant material and labor standards. | 6. Relevance of trust and social networking mechanisms and spaces. | 7. Conscious buying agents to purchase cocoa with minimum quality conditions. | 6. Networking support. | |||

| 7. Existence of a business plan. | 8. Marketing legality. | 7. Development of research programs with impact on the chain’s competitiveness. | ||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Escobar, S.; Santander, M.; Useche, P.; Contreras, C.; Rodríguez, J. Aligning Strategic Objectives with Research and Development Activities in a Soft Commodity Sector: A Technological Plan for Colombian Cocoa Producers. Agriculture 2020, 10, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10050141

Escobar S, Santander M, Useche P, Contreras C, Rodríguez J. Aligning Strategic Objectives with Research and Development Activities in a Soft Commodity Sector: A Technological Plan for Colombian Cocoa Producers. Agriculture. 2020; 10(5):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10050141

Chicago/Turabian StyleEscobar, Sebastián, Margareth Santander, Pilar Useche, Carlos Contreras, and Jader Rodríguez. 2020. "Aligning Strategic Objectives with Research and Development Activities in a Soft Commodity Sector: A Technological Plan for Colombian Cocoa Producers" Agriculture 10, no. 5: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10050141

APA StyleEscobar, S., Santander, M., Useche, P., Contreras, C., & Rodríguez, J. (2020). Aligning Strategic Objectives with Research and Development Activities in a Soft Commodity Sector: A Technological Plan for Colombian Cocoa Producers. Agriculture, 10(5), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10050141