Grants for Local Community Initiatives as a Way to Increase Public Participation of Inhabitants of Rural Areas

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Obtaining data from announcements regarding the results of contests for funding;

- Obtaining data from the local data bank of GUS regarding realising the expenditure in the framework of the FS in municipalities;

- Comparative analysis concerning the awarded grants combined with the functioning of the FS in municipalities in individual years;

- Analysis of the scale of engagement of sołectwa in individual municipalities during the project’s realisation.

3. State of the Art

3.1. Regional Development

3.2. Social Capital and Civil Society in Regional Development Policy

3.3. Regional Self-Government in Poland Versus Regional Development, Civil Society, and Citizen Participation in Public Management

- The necessity of inhabitants undertaking bottom-up initiatives;

- Creating a project based on a discussion process involving all inhabitants and achieving a consensus (co-creation);

- The possibility of the active engagement of inhabitants when realising a project (co-production);

- The lack of necessity to co-finance the project from other sources;

- The possibility of applying for project funding with an omission of local authorities;

- The obligatory nature of projects being approved by the donor;

- Matching the regional development strategy and compliance with the tasks of the regional local government authorities;

- Multicriteria assessment of a complex project, and qualification for funding according to the contest’s principles.

4. Results

4.1. Grant Programmes from Regional Self-Governments for Small Local Communities in Rural Areas in Poland

- -

- Supporting, stimulating, and promoting the activity of the region’s rural population;

- -

- Improving the quality of life in villages;

- -

- Promoting actions supporting the creation of conditions for the development of social capital and a sense of regional identity;

- -

- Integration of the rural community;

- -

- Supporting local democracy and civil society.

- -

- The requirement of the beneficiary’s own financial contribution;

- -

- The requirement of prior execution of the project for which the financial award will be granted (also limits the chances of poorer and less developed municipalities);

- -

- Making the possibility of the grant application conditional on participation in another programme intended for villages—the Wielkopolskie Voivodeship is an example. Such a mechanism causes some municipalities to be excluded from the competition for formal reasons;

- -

- The lack of the possibility of co-financing the project’s implementation with other sources (e.g., EU funds or FSs);

- -

- There may be a significant narrowing of the catalogue of projects eligible for financing.

4.2. Case Study

- First of all, creating and submitting applications:

- The inhabitants of a given town, during a civil meeting (of the whole community), by way of a resolution, undertake a decision concerning the choice of project they would like to realise. The meeting of the inhabitants is for presenting ideas and discussing them. The inhabitants do not need to limit themselves to just one meeting; however, the result of the vote on the choice of the discussed projects (resolution) is binding;

- The village leader (the representative of the inhabitants) turns to the municipal authorities with a motion for a grant to be obtained from the voivodeship’s local government for a given project. A local community cannot directly apply to the voivodeship local government, due to legal reasons, and to the fact that there are a limited number of projects that can be financed in the area of a given municipality in a given year;

- Municipal authorities make their choice of a maximum of three projects for a given year, and direct the motion for the funding of them to the voivodeship’s local government. Here, we face the first issue related to the arbitrariness of the selection of projects to be financed at the level of a municipality.

- Secondly, the awarding of a grant and realising projects:

- The donor (voivodeship local government) carries out an initial assessment of the conceptual and formal correctness of the applications;

- The donor (voivodeship local government), based on the criteria, then creates a ranked list of projects, and assigns resources in accordance with the order of the projects on the list;

- The funds are assigned in accordance with the plan for realising the submitted projects, and then settled in accordance with the provisions concerning spending public funds (including verification of the manner of project realisation).

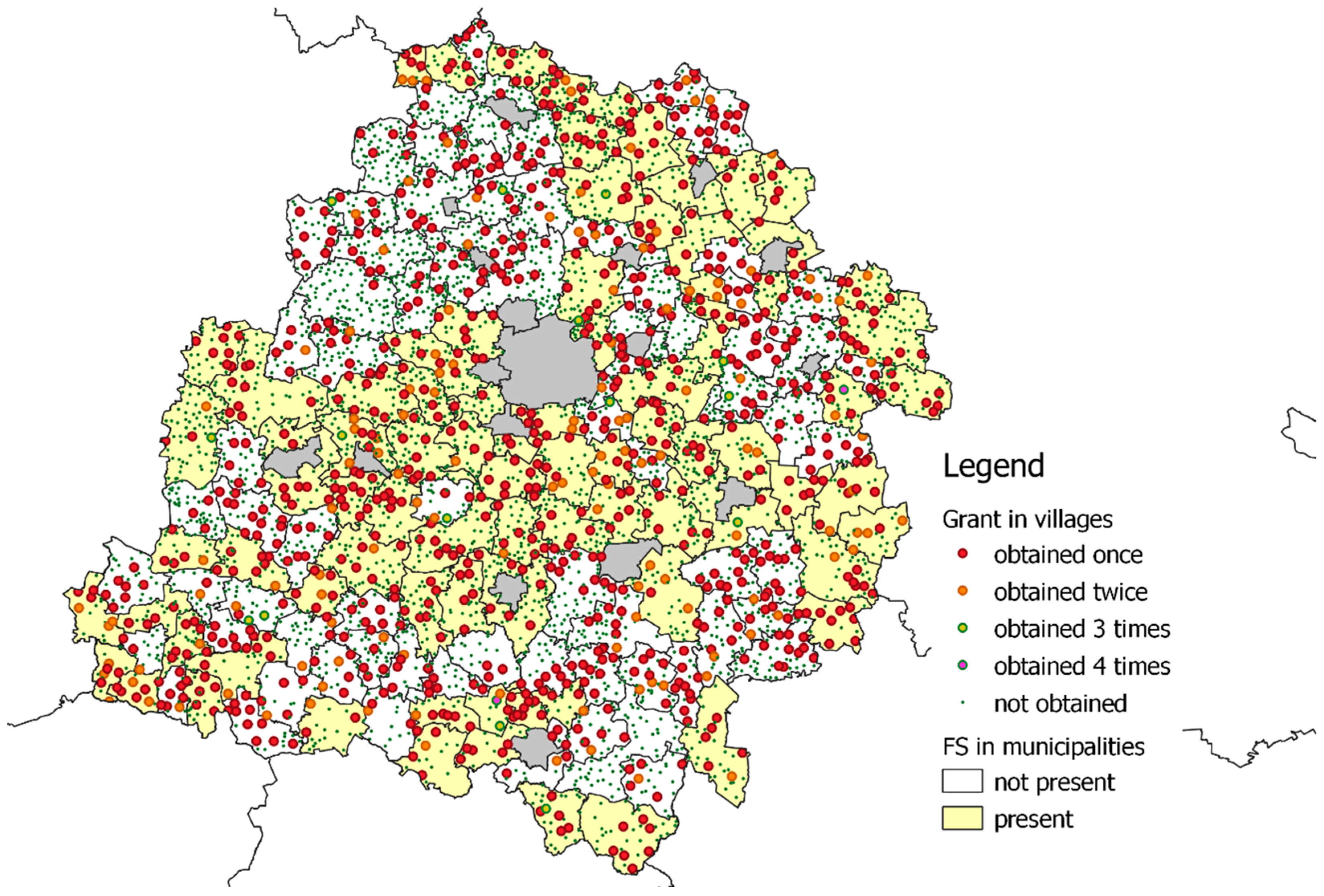

4.3. Quantitative Data Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The substantive scope of the financed projects ought to concern matters that are of importance to the local community (attracting the attention of the inhabitants);

- The community ought to be able to freely choose the goal of a project through the process of deliberation, engaging the majority of inhabitants and leading to a consensus (building the skills of discussing and reaching common goals);

- The inhabitants should be able to actively participate in realising a project (building the feeling of co-responsibility, social capital);

- The process of applying for funding ought to be as independent of “intermediaries” as possible—that is, of local authorities carrying out the initial selection of projects (limiting bureaucracy, limiting politicisation of the process);

- The inclusion of the co-creation and co-production of public services and goods as an element of assessing projects (promoting co-participation of inhabitants).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woolcock, M.; Narayan, D. Social Capital: Implications for Development Theory, Research, and Policy. World Bank Res. Obs. 2000, 15, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woodhouse, A. Social Capital and Economic Development in Regional Australia: A Case Study. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigilia, C. Social Capital and Local Development. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2001, 4, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suebvises, P. Social Capital, Citizen Participation in Public Administration, and Public Sector Performance in Thailand. World Dev. 2018, 109, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, J.T. Bonding Social Capital and Collective Action: Associations with Residents’ Perceptions of Their Neighbourhoods. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 29, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J. Participatory Budgeting in Poland in 2013–2018—Six Years of Experiences and Directions of Changes. In Hope for Democracy. 30 Years of Participatory Budgeting Worldwide; Dias, N., Ed.; Epopeia Records: Faro, Portugal; Oficina coordination: Faro, Portugal, 2018; pp. 337–354. ISBN 978-989-54-1670-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, M. Participatory Budgeting, Rural Public Services and Pilot Local Democracy Reform. Field Actions Sci. Rep. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J.; Svobodová, L. How a Participatory Budget Can Support Sustainable Rural Development—Lessons From Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OIDP. Available online: https://oidp.net/en/practice.php?id=1265 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Buele, I.; Vidueira, P.; Guevara, M.G. Implementation Model and Supervision of Participatory Budgeting: An Ecuadorian Approach Applied to Local Rural Governments. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1779507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buele, I.; Vidueira, P.; Yagüe, J.L.; Cuesta, F. The Participatory Budgeting and Its Contribution to Local Management and Governance: Review of Experience of Rural Communities from the Ecuadorian Amazon Rainforest. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdo, M. Deliberative Capital: Recognition in Participatory Budgeting. Crit. Policy Stud. 2016, 10, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarek-Szczepańska, M. Wiejski kapitał społeczny we współczesnej Polsce. Przegląd badań i uwagi metodyczne. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Geogr. Socio-Oeconomica 2013, 13, 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- GUS BDL GUS. Available online: www.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Storper, M. The Regional World: Territorial Development in a Global Economy; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 1-57230-315-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bachtler, J.; Yuill, D. Policies and Strategies for Regional Development: A Shift in Paradigm? University of Strathclyde, European Policies Research Centre: Glasgow, UK, 2001; ISBN 1-871130-52-2. [Google Scholar]

- Capello, R. Regional Growth and Local Development Theories: Conceptual Evolution over Fifty Years of Regional Science. Géographie Économie Société 2009, 11, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hassink, R. Regional Resilience: A Promising Concept to Explain Differences in Regional Economic Adaptability? Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; Rodriguez-Pose, A.; Tomaney, J. Local and Regional Development; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-317-66415-4. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Regional Development Policy—OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/regional/regionaldevelopment.htm (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- Pike, A.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Tomaney, J. What Kind of Local and Regional Development and for Whom? Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nijkamp, P.; Abreu, M.A. Regional Development Theory; Vrije Universiteit, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bærenholdt, J.O. Regional Development and Noneconomic Factors. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 181–186. ISBN 978-0-08-044910-4. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D.; Leonardi, R.; Nanetti, R. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A. An Institutionalist Perspective on Regional Economic Development. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1999, 23, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-19-282080-8.

- Stafford-Smith, M.; Griggs, D.; Gaffney, O.; Ullah, F.; Reyers, B.; Kanie, N.; Stigson, B.; Shrivastava, P.; Leach, M.; O’Connell, D. Integration: The Key to Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biermann, F.; Kanie, N.; Kim, R.E. Global Governance by Goal-Setting: The Novel Approach of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, E.; Linnerud, K.; Banister, D. Sustainable Development: Our Common Future Revisited. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 26, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations. Agenda 21; United Nations: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Millenium Declaration. Available online: http://www.un.org/en/development/devagenda/millennium.shtml (accessed on 10 November 2018).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J.; Svobodova, L. Towards a Smart and Sustainable City with the Involvement of Public Participation-The Case of Wroclaw. Sustainability 2019, 11, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drexhage, J.; Murphy, D. Sustainable Development: From Brundtland to Rio 2012; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Delivering the Sustainable Development Goals at Local and Regional Level. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/delivering-sdgs-local-regional-level.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Global Taskforce. Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments. Available online: https://www.global-taskforce.org/ (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- OECD/CoR. Survey Results Note: The Key Contribution of Regions and Cities to Sustainable Development. Available online: https://cor.europa.eu/en/events/Documents/ECON/CoR-OECD-SDGs-Survey-Results-Note.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Fenton, P.; Gustafsson, S. Moving from High-Level Words to Local Action—Governance for Urban Sustainability in Municipalities. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graute, U. Local Authorities Acting Globally for Sustainable Development. Reg. Stud. 2016, 50, 1931–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, S.; Ivner, J. Implementing the Global Sustainable Goals (SDGs) into Municipal Strategies Applying an Integrated Approach. In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; World Sustainability Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 301–316. ISBN 978-3-319-63007-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D. A Commentary on the Localisation of the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Public Aff. 2020, 20, e1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, D.; Gowsy, S.; Riffon, O.; Boucher, J.-F.; Dubé, S.; Villeneuve, C. A Systemic Approach for Sustainability Implementation Planning at the Local Level by SDG Target Prioritization: The Case of Quebec City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierstein, A.; Walser, M. Sustainable Regional Development: Interplay of Topdown and Bottom-up Approaches; European Regional Science Association (ERSA): Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, F.; Biggs, S. Evolving Themes in Rural Development 1950s-2000s. Dev. Policy Rev. 2001, 19, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldock, D.; Dwyer, J.; Lowe, P.; Petersen, J.-E.; Ward, N. The Nature of Rural Development: Towards a Sustainable Integrated Rural Policy in Europe; Institute for European Environmental Policy: London, UK, 2001; ISBN 1-8730906-40-4. [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg, J.D.; Renting, H.; Brunori, G.; Knickel, K.; Mannion, J.; Marsden, T.; de Roest, K.; Sevilla-Guzman, E.; Ventura, F. Rural Development: From Practices and Policies towards Theory. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, C.L. Rural Development. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Farazmand, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-3-319-31816-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, W.A.; Hite, J.C. Theory in Rural Development: An Introduction and Overview. Growth Chang. 1998, 29, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Rural Development (English); The World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Moseley, M.J. Rural Development: Principles and Practice; SAGE: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7619-4766-0. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K. Rural Development: Principles, Policies and Management; SAGE Publications India: New Delhi, India, 2009; ISBN 978-81-321-0107-9. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. European Union Cork 2.0 Declaration; European Union: Mestreech, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Todaro, M.P. Economic Development; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-8013-1081-2. [Google Scholar]

- Akgun, A.A.; Baycan, T.; Nijkamp, P. Rethinking on Sustainable Rural Development. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryden, J.M. Is There a “New Rural Policy” in OECD Countries? Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED455048 (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- OECD. The Well-Being of Nations: The Role of Human and Social Capital; OECD: Paris, France, 2001; ISBN 978-92-64-18589-0. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-684-83283-8. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock, M. Social Capital in Theory and Practice: Where Do We Stand. Soc. Cap. Econ. Dev. Well-Dev. Ctries. 2002, 1, 18–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bobbio, L. Building Social Capital through Democratic Deliberation: The Rise of Deliberative Arenas. Soc. Epistemol. 2003, 17, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocchi, G.; Heller, P.; Silva, M.K. Making Space for Civil Society: Institutional Reforms and Local Democracy in Brazil. Soc. Forces 2008, 86, 911–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Social Capital and Civil Society; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mandarano, L.A. Evaluating Collaborative Environmental Planning Outputs and Outcomes: Restoring and Protecting Habitat and the New York—New Jersey Harbor Estuary Program. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2008, 27, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoforou, A. Social Capital and Local Development in European Rural Areas: Theory and Empirics. In Social Capital and Local Development: From Theory to Empirics; Pisani, E., Franceschetti, G., Secco, L., Christoforou, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 43–60. ISBN 978-3-319-54277-5. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, G.; Plümper, T.; Baumann, S. Bringing Putnam to the European Regions: On the Relevance of Social Capital for Economic Growth. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2000, 7, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engbers, T.A.; Rubin, B.M. Theory to Practice: Policy Recommendations for Fostering Economic Development through Social Capital. Public Adm. Rev. 2018, 78, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlund, H.; Larsson, J.P. Local Social Capital and Regional Development. Handb. Reg. Sci. 2021, 721–735. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler-Koch, B.; Quittkat, C. What Is Civil Society and Who Represents Civil Society in the EU?—Results of an Online Survey among Civil Society Experts. Policy Soc. 2009, 28, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards, M. The Oxford Handbook of Civil Society; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-19-933014-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. Read. Econ. Sociol. 2002, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plann. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hussay, S. International Public Participation Models 1969–2020. Bang the Table 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, D.M. A New Ladder of Citizen Participation. Natl. Civ. Rev. 1988, 77, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, D. The Guide to Effective Participation; Partnership: Brighton, UK, 1994; ISBN 978-1-870298-00-1. [Google Scholar]

- Timney, M.M. Overcoming Administrative Barriers to Citizen Participation: Citizens as Partners, Not Adversaries. In Government Is US. Strategies for Anti-Government Era; King, C.S., Stivers, C., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; pp. 88–101. ISBN 0761908811.

- IAP2 International Association for Public Participation (IAP2). Available online: https://www.iap2.org/page/resources (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Bloomberg, L. Public Value Governance: Moving Beyond Traditional Public Administration and the New Public Management. Public Adm. Rev. 2014, 74, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestoff, V. Citizens and Co-Production of Welfare Services—Childcare in Eight European Countries. Public Manag. Rev. 2006, 8, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. A Typology of Public Engagement Mechanisms. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2005, 30, 251–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. Beyond the Ballot: 57 Democratic Innovations from Around the World: A Report for the Power Inquiry; Power Inquiry: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-0-9550303-0-7. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.; Calabese, T.; Harju, S. A Theory of Participatory Budgeting Decision Making as a Form of Empowerment; CUNY: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brandsen, T.; Steen, T.; Verschuere, B. Co-Production and Co-Creation: Engaging Citizens in Public Services; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-315-20495-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy, and Development. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raszkowski, A.; Bartniczak, B. Towards Sustainable Regional Development: Economy, Society, Environment, Good Governance Based on the Example of Polish Regions. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2018, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Rada Ministrów. Strategia Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Polski Do 2025 Roku; Rada Ministrów: Warszawa, Polska, 1999.

- Ministerstwo Rozwoju. Strategia Na Rzecz Odpowiedzialnego Rozwoju; Ministerstwo Rozwoju: Warszawa, Polska, 2016.

- Rada Ministrów. Krajowa Strategia Rozwoju Regionalnego 2010-2020: Regiony, Miasta, Obszary Wiejskie; Rada Ministrów: Warszawa, Polska, 2010.

- The Participatory Budgeting World Atlas; Dias, N.; Enriquez, S.; Julio, S. (Eds.) Epopeia-Make It Happen: Faro, Portugal; Oficina: Faro, Portugal, 2019; ISBN 978-989-54-1673-8. [Google Scholar]

- Feltynowski, M. Local Initiatives for Green Space Using Poland’s Village Fund: Evidence from Lodzkie Voivodeship. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2020, 50, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczudlińska-Kanoś, A. Participatory Democracy to the Contemporary Problems of Polish Social Policy. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 9, 1988–1994. [Google Scholar]

- Olejniczak, J.; Bednarska-Olejniczak, D. Co-Production of Public Services In Rural Areas—The Polish Way? In Proceedings of the 22nd International Colloqium on Regional Sciences; Masaryk University: Velke Bilovice, Czech Republic, 2019; pp. 418–425. [Google Scholar]

- Olejniczak, J.; Bednarska-Olejniczak, D. Solecki Fund as a Kind of Participatory Budget for Rural Areas Inhabitants in Poland. In Vision 2025: Education Excellence and Management of Innovations through Sustainable Economic Competitive Advantage; Soliman, K.S., Ed.; International Business Information Management Association: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 10815–10826. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J.; Klímová, V. Participatory Budget at The Regional Self-Government. Participation of Citizens as An Element of Intraregional Policy of Voivodeships In Poland. In Education Excellence and Innovation Management: A 2025 Vision to Sustain Economic Development during Global Challenges; International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA): Sevilla, Spain, 2020; pp. 828–837. ISBN 9780999855141. [Google Scholar]

- Sintomer, Y.; Herzberg, C.; Röcke, A.; Allegretti, G. Transnational Models of Citizen Participation: The Case of Participatory Budgeting. J. Public Delib. 2012, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulamin udzielania z Budżetu Województwa Łódzkiego Pomocy Finansowej Jednostkom Samorządu Terytorialnego Województwa Łódzkiego w Formie Dotacji Celowej, Przeznaczonej Na Dofinansowanie Zadań Własnych Gminy w Zakresie Realizacji Małych Projektów Lokalnych Realizowanych Na Terenach Wiejskich; Zarząd Województwa Łódzkiego: Łódź, Polska, 2020.

- The Development Strategy for the Lodz Region for the Years 2007–2020; Zarząd Województwa Łódzkiego: Łódź, Polska, 2006.

| Voivodeship | Main Goals of the Grant Programmes |

|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | Supporting the activity of the rural population in the region by meeting the most urgent needs for the improvement of living conditions in rural areas. |

| Łódzkie | Supporting and promoting local community initiatives. |

| Małopolskie | Supporting the activity of local communities by awarding villages and their inhabitants who are actively involved in making Małopolska’s villages more attractive and improving their residents’ quality of life. |

| Mazowieckie | Promoting actions stimulating, for example, the multifunctional development of rural areas, the effective use of the potential of rural areas, and promoting actions supporting the creation of conditions for the development of social capital and a sense of regional identity. |

| Opolskie | Enabling the inhabitants of villages to influence the allocation of funds from the voivodeship budget to projects that support, promote, develop, integrate, and stimulate the activation of local communities. |

| Podlaskie | Integrating the rural community, forming a new concept of an innovative village, activating local communities, and disseminating and promoting the Smart Villages concept in the rural space. |

| Pomorskie | Supporting the development of local democracy and civil society. Implementing the ideas contained in the strategic documents of the local government. Strengthening local identity and integration. Effectively using and stimulating the growth potential of rural areas. Improving the spatial order. Preserving the cultural and natural heritage and landscape. |

| Śląskie | Involving residents in achieving the following goals: shaping the national and civic awareness of the inhabitants; stimulating economic activity; increasing the competitiveness and economic innovation of the voivodeship; preserving the value of the cultural and natural environment; shaping and maintaining of the spatial order. |

| Warmińsko- Mazurskie | Promoting activities for modernising rural areas through supporting projects that increase the level of involvement of local communities; building strong social capital in line with the provincial development strategy; selecting and recommending projects to be subsidised. |

| Wielkopolskie | Supporting initiatives of inhabitants of villages participating in the “Wielkopolska Renewal of Villages” programme for the development of their own village. |

| Zachodnio pomorskie | Supporting the development of local democracy and civil society, and strengthening the identity and integration of the local community at the initiative of the village. Distinguishing those villages that undertake particularly important initiatives in support of local democracy and civil society. Identifying and disseminating effective practices of supporting local democracy and developing civil society. |

| Voivodeship | Maximum Grant per Project (PLN) (Year) | Own Contribution | Co-Funding from Sołecki Fund | Other External Co-Funding | Fits into the Region’s Strategy? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 30,000 (2021) | Yes, mandatory over 50% of eligible costs | - | No | - |

| Łódzkie | 10,000 (2021) | Yes, possible | - | - | Yes |

| Małopolskie | 10,000 to 60,000 | - | - | - | - |

| Mazowieckie | 10,000 (2021) | Yes, mandatory over 50% of eligible costs | Yes | No | Yes |

| Opolskie | 5000 (2020) | Yes, mandatory over 20% of grant | Yes | No | - |

| Podlaskie | 15,000 (2020) | Yes, mandatory over 50% of total costs | - | No | - |

| Pomorskie | 10,000 (2020) | Yes, possible | - | - | Yes |

| Śląskie | 10,000 or 6000 (2020) | Yes, mandatory over 20% of eligible costs | Yes | No | - |

| Warmińsko-Mazurskie | 15,000 (2020) | Yes, mandatory over 20% of total costs | Yes | No | Yes |

| Wielkopolskie | Min 10,000, max 30,000 (2021) | Yes, mandatory over 30% of eligible costs | Yes | No | Yes |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 10,000 (2021) | Yes, possible | - | Yes | Yes |

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grants per municipality: 1 | 47 | 60 | 23 | 11 | 61 |

| Grants per municipality: 2 | 6 | 61 | 48 | 9 | 38 |

| Grants per municipality: 3 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 127 | 55 |

| Grants per municipality: 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total municipalities with grants | 54 | 121 | 132 | 147 | 154 |

| More than 1 grant per municipality | 7 | 61 | 109 | 136 | 93 |

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total municipalities | 159 | 159 | 159 | 159 | 159 | 159 |

| Total municipalities with grants | 54 | 121 | 132 | 147 | 154 | - |

| Total unique municipalities (2016–2020) | - | - | - | - | - | 158 |

| Total municipalities without FS | 76 | 82 | 76 | 76 | 76 * | - |

| Unique municipalities without FS with grants | 27 | 59 | 58 | 68 | 72 | - |

| Unique municipalities without FS (2016–2020) | - | - | - | - | - | 75 |

| Amount allocated to grants (million PLN) | 0.5 | 1.5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | - |

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grants per municipality: 1 | 47 | 60 | 23 | 11 | 61 |

| Grants per municipality: 2 | 12 | 122 | 96 | 18 | 38 |

| Grants per municipality: 3 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 381 | 165 |

| Grants per municipality: 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total grants | 63 | 182 | 302 | 410 | 302 |

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grants per municipality: 1 | 23 | 29 | 9 | 4 | 25 |

| Grants per municipality: 2 | 4 | 30 | 18 | 6 | 16 |

| Grants per municipality: 3 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 58 | 31 |

| Grants per municipality: 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total municipalities | 27 | 59 | 58 | 68 | 72 |

| More than 1 grant per municipality | 4 | 30 | 49 | 64 | 47 |

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grants per municipality: 1 | 24 | 31 | 14 | 7 | 36 |

| Grants per municipality: 2 | 2 | 31 | 30 | 3 | 22 |

| Grants per municipality: 3 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 69 | 24 |

| Grants per municipality: 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total municipalities | 27 | 62 | 74 | 79 | 82 |

| More than 1 grant per municipality | 3 | 31 | 60 | 72 | 46 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J.; Klímová, V. Grants for Local Community Initiatives as a Way to Increase Public Participation of Inhabitants of Rural Areas. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11111060

Bednarska-Olejniczak D, Olejniczak J, Klímová V. Grants for Local Community Initiatives as a Way to Increase Public Participation of Inhabitants of Rural Areas. Agriculture. 2021; 11(11):1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11111060

Chicago/Turabian StyleBednarska-Olejniczak, Dorota, Jarosław Olejniczak, and Viktorie Klímová. 2021. "Grants for Local Community Initiatives as a Way to Increase Public Participation of Inhabitants of Rural Areas" Agriculture 11, no. 11: 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11111060

APA StyleBednarska-Olejniczak, D., Olejniczak, J., & Klímová, V. (2021). Grants for Local Community Initiatives as a Way to Increase Public Participation of Inhabitants of Rural Areas. Agriculture, 11(11), 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11111060