Cereal-Legume Value Chain Analysis: A Case of Smallholder Production in Selected Areas of Malawi

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Value Chain Analysis

2.1.1. Value Chain Map

2.1.2. SWOT Analysis

2.2. Policy Analysis

2.3. Source of Information

3. Results

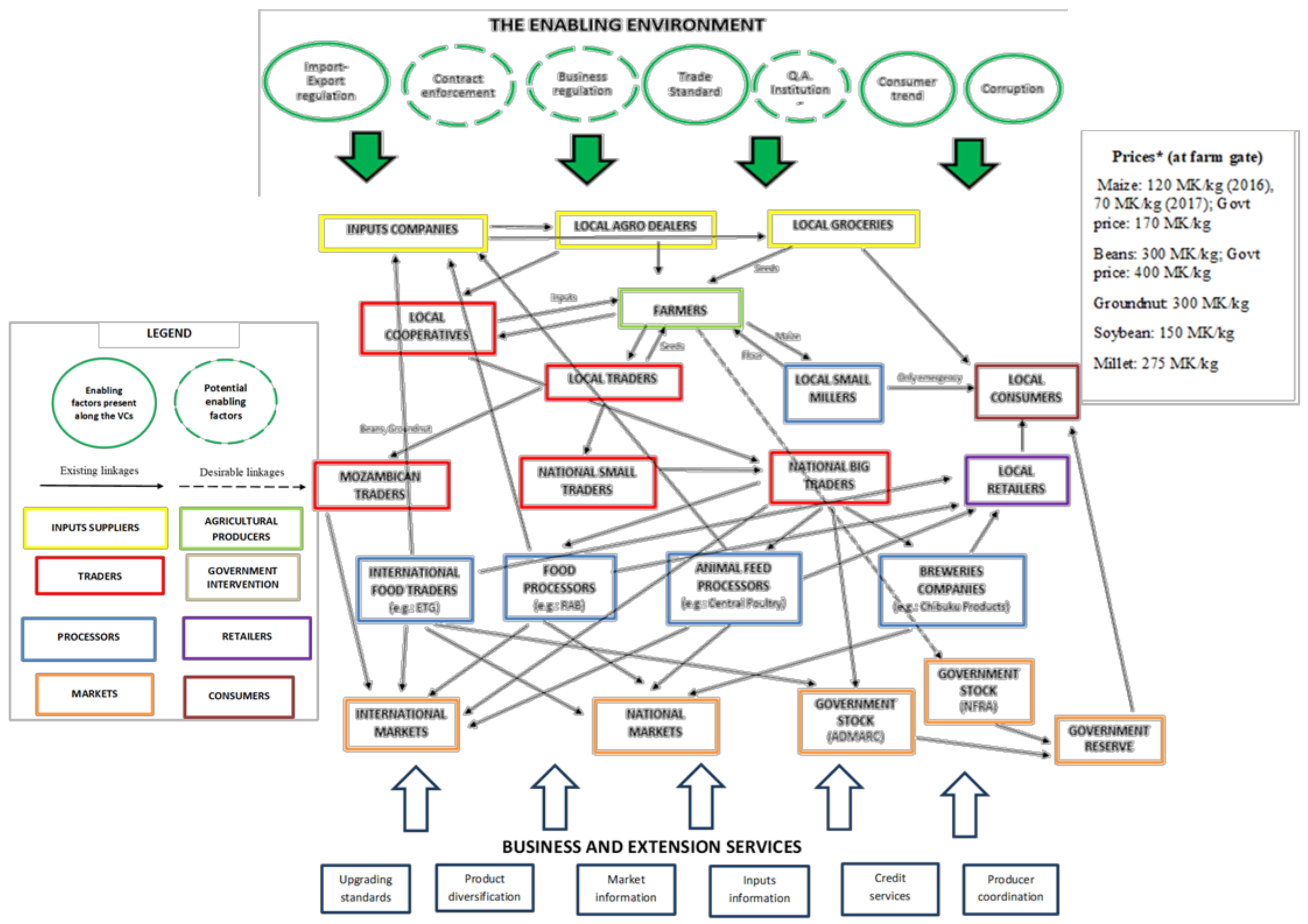

3.1. VC MAP and Characteristics of the VC Actors

- Inputs suppliers

- Agro-dealers

- Traders

- Cooperatives

- Processors

- Enabling environment factors

- Business and extension services

3.2. SWOT Analysis

3.3. Policy Analysis

3.3.1. Value Chain Readiness

3.3.2. Policies in Supporting Smallholders’ Access to Market

3.3.3. Policy Strategies for Promoting Smallholders’ Value Chain Readiness

3.3.4. The Role of VC Actors

3.3.5. Policy Harmonisation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Developing Sustainable Food VCs—Guiding Principles; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014.

- Cacchiarelli, L.; Sorrentino, A. Market power in food supply chain: Evidence from Italian pasta chain. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2129–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, A.; Russo, C.; Cacchiarelli, L. Market power and bargaining power in the EU food supply chain: The role of Producer Organizations. New Medit. 2018, 17, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagomoka, T.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Pitoro, R. Value chain analysis of traditional vegetables from Malawi and Mozambique. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Nagothu, U.S. (Ed.) Agricultural Development and Sustainable Intensification: Technology and Policy Challenges in the Face of Climate Change; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfai, M.; Branca, G.; Cacchiarelli, L.; Perelli, C.; Nagothu, U.S. Transition towards bio-based economy in small-scale agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa through sustainable intensification. In The Bioeconomy Approach; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Branca, G.; Arslan, A.; Paolantonio, A.; Grewer, U.; Cattaneo, A.; Cavatassi, R.; Vetter, S. Assessing the economic and mitigation benefits of climate-smart agriculture and its implications for political economy: A case study in Southern Africa. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 125161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, M. Using VC Approaches in Agribusiness and Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Methodological Guide. Report Prepared for the World Bank by J.E. Austin Associates, Inc. 2007. Available online: http://www.technoserve.org/files/downloads/vcguidenov12-2007.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2019).

- Fowler, B.; Brand, M. Pathways out of Poverty: Applying Key Principles of the Value Chain Approach to Reach the Very Poor; USAID, Microreport: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 173.

- Stoian, D.; Donovan, J.; Fisk, J.; Muldoon, M. Value chain development for rural poverty reduction: A reality check and a warning. Enterp. Dev. Microfinanc. 2012, 23, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Devaux, A.; Torero, M.; Donovan, J.; Horton, D. Agricultural innovation and inclusive value-chain development: A review. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 8, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donovan, J.; Stoian, D. 5 Capitals: A Tool for Assessing the Poverty Impacts of Value Chain Development; Technical Series 55; Rural Enterprise Development Collection 7; CATIE: Turrialba, Costa Rica, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, J.; Poole, N. Asset building in response to value chain development: Lessons from taro producers in Nicaragua. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2013, 11, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Indicator: Structure of Output. 2014. Available online: http://wdi.worldbank.org/table/4.2 (accessed on 25 May 2019).

- Dorward, A.; Chirwa, E. The Malawi Agricultural Input Subsidy Programme: 2005-6 to 2008-9. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2011, 9, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellis, F.; Manda, E. Seasonal Food Crises and Policy Responses: A Narrative Account of Three Food Security Crises in Malawi. World Dev. 2012, 40, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSO. Integrated Household Survey 2010–11: Household Socio Economic Characteristics Report; National Statistical Office: Zomba, Malawi, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, R.; Nchimbi-Msolla, S.; Murage, A.; Moeletsi, M.; Magalasi, M.; Mutimura, M.; Westengen, O.T. From Policy Promises to Result through Innovation in African Agriculture? World 2021, 2, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mango, N.; Mapemba, L.; Tchale, H.; Makate, C.; Dunjana, N.; Lundy, M. Maize value chain analysis: A case of smallholder maize production and marketing in selected areas of Malawi and Mozambique. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1503220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, G.; Perelli, C. Clearing the air: Common drivers of climate-smart smallholder food production in Eastern and Southern Africa. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 121900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snapp, S.S.; Blackie, M.J.; Gilbert, R.A.; Bezner Kerr, R.; Kanyama-Phiri, G.Y. Biodiversity can support a greener revolution in Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 107, 20840–20845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mhango, J.; Dick, J. Analysis of fertilizer subsidy programs and ecosystem services in Malawi. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2011, 26, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, G.; Cacchiarelli, L.; Maltsoglou, I.; Rincon, L.; Sorrentino, A.; Valle, S. Profits versus jobs: Evaluating alternative biofuel value-chains in Tanzania. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellin, J.; Meijer, M. Guidelines for Value Chain Analysis; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2006; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/bq787e/bq787e.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2019).

- Neven, D. Three Steps in VC Analysis; microNote; United States Agency for International Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.microlinks.org/sites/microlinks/files/resource/files/mn_53_three_steps_in_vc_analysis.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2019).

- Webber, C.M.; Labaste, P. Building Competitiveness in Africa’s Agriculture: A Guide to VC Concepts and Applications; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Strengthening Sector Policies for Better Food Security and Nutrition Results. 2017. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7910e.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2019).

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. In The Qualitative Researchers’ Companion; Huberman, A.M., Miles, M.B., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, M.; Stašys, R.; Pellegrini, G. Agri-Food Supply Chain Optimization through the Swot Analysis. Manag. Theory Stud. Rural. Bus. Infrastruct. Dev. 2018, 40, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NIBIO and BecA-ILRI Hub. National Ethics Council (NEC)–Requirement No. 1. Report to the EC. In Innovations in Technology, Institutional and Extension Approaches towards Sustainable Agriculture and Enhanced Food and Nutrition Security in Africa; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Inputs | Output Production | Output Processing | Output Marketing and Trade/Export | Governance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strengths | • Active local and international input suppliers • High quality traditional seeds supply guaranteed by cooperatives through Seed Loan Program • Existing quality control and inspection system on commercialised seeds | • High quality grain • Existing coordination between technical assistance providers | • Developed and differentiated sector (e.g., beer, animal feed, nutritional and fortified food products, etc.) • Availability of local milling station for local maize varieties processing | • Established export channels | • Cooperatives’ system is developed in the areas • National and international traders operate in the areas for different cereals and legumes |

| Weaknesses | • Poor coverage of extension services • Inadequate fertiliser subsidy system which only targets the most vulnerable farmers without providing technical assistance • Informal seed sector lacks quality control (selling ‘fake seeds’ and uncertified seed) • Slow release process for new seed varieties | • Low and unstable prices • Lack of governmental monitoring on the real implementation of the maize floor price • Weak local infrastructure constrains access to local markets • Insufficient and poor storage facilities • Lack of formal organisational arrangements with traders • NFRA fails to purchase grain from local farmers • Insufficient capital to buy inputs and arrange product storage • Lack of policies conducive for agricultural innovations adoption | • Lack storage facilities (for local millers) • Unstable supply of electricity (for local millers) • Heterogeneity and unstable raw material supply | • Heterogeneous grain supply affecting competitiveness • Frequent changes in the trade regulation (e.g., export ban for maize) • Insufficient market price information (for small traders) • Low capital and high loan interest rate (for small traders) • Small traders are not able to gain access to ADMARC purchases • High storage waste (about 20% of production) | • Several factors (unstable prices, climatic conditions, heterogeneity of production) limit the possibility of supply chain agreements involving smallholders. • only a few traders with transportation facilities are able to reach more remote areas • Scarce presence of big millers in the production areas limits the creation of added value in the maize VC |

| Opportunities | • Enlarging the use of suitable varieties to meet market demand • Increasing availability of high quality seeds adapted to climate change and local conditions | • High awareness by government on the importance of maize-legumes systems • Scope to improve crop rotations with legumes to respond to climate resilience and market demand • Improving farmers’ capacity building through Leading Farmers and Village demonstration plot approaches | • Expanding export toward Mozambique (for local and national traders) | • Including smallholder system in the VC managed by national and international traders through intermediation of the cooperatives which operate in the area | |

| Threats | • Potential dependence on few dominant input suppliers | • Unstable weather conditions • Prices instability • Prevalence of monocropping | • Unstable national and international price • Unstable national supply | • Unstable national and international price • Unstable national supply • Unsafe road infrastructures and high frequency of thefts • Illegal markets • Frequent changes in trade regulation (e.g., export ban for maize) | • Climatic conditions extremely unstable (the country is experiencing frequent droughts and national disasters) |

| Policy Programme | Policy Measure | Policy Objectives | Implementation Level and Effectiveness | Limiting factors | Suggested Policy Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Agriculture Policy | Strengthen farmer organisations through improving the development, branding, quality and marketing of their products, establishing labour standards, and building skills in price negotiation | • Performance and outreach of farmer organisations strengthened at all levels | • Implementation level for these measures is considered medium/low. Data from the household survey indicate that only 23% of respondents have access to groups and cooperatives. • MAP members recognised the high effectiveness potential of this instrument. | • Insufficient availability of financial resources • Low availability of extension officers to create synergies • Inefficient supervision and distribution of the available officers • Low employment rate which does not match with the actual demands • Lack of laws and regulations that can be used to enforce this instrument • The private sector is not perceived as an extension provider | • Increasing farmer organisations’ capacity to support loan access for members by means of partnerships with big companies • Implementing the subsidies programmes through farmer organisations • Increasing capacity building of farmer organisations’ leaders • Promoting a stronger partnership between researchers, extension officers and farmer organisations to enhance innovations and soil management/water conservation practices uptake • Increasing available resources to enhance the portfolio of farmer organisations’ activities (this includes specific actions to engage with potential members) • Increasing the available coordination mechanisms to support organisations’ linkages with other relevant VC actors; • The Ministry of Trade should facilitate the certification of other organisations to train groups on cooperatives on their behalf. |

| National Agriculture Policy | Establish an appropriate stakeholder and policymaker representation and coordination body to develop value chains | • Promote competitiveness of agriculture marketing value chains | • Implementation level for these measures is considered medium. Despite the negative effect of decentralisation, which disregarded the local structure of the agricultural sector, new coordination mechanisms (such as DAES) are emerging. • MAP members considered the potential effectiveness of this policy instrument high. | • Lack of financial resources • Lack of consideration for the local structure of the agricultural sector • Poor empowerment of District Council • High intermediation level in commercial transactions • Many companies send intermediaries from outside the study area during harvest season, but they do not have a mandate to negotiate with other local actors. | • Mechanisms that encompass all the players in the agricultural chain starting from providers to buyers (private as well as public, e.g., ADMARC) should be developed; • District Councils need to be empowered to be able to discipline VC actors’ inappropriate behaviours; • Buyers should be engaged along the productive season to understand the challenges farmers face and make their contribution to finding viable solutions; • All relevant stakeholders within the agriculture sector should be involved when setting up a floor price. |

| National Agricultural Investment Plan | Delivery of relevant, evidence-based extension advice in a demand-driven and participatory way | • Improved access to extension services • Promote the adoption of agricultural innovations | • Implementation level for this measure is considered low due to the insufficient number of extension officers in the area. Data from the household survey indicate that only 30% of respondents have had access to extension services. • The effectiveness of this policy instrument was considered high. | • Limited financial resources • Limited number of available extension officers • Many smallholders live in remote areas difficult to access • NGO and support actors depend on extension officers for delivery • The poor coordination existing between actors make unclear the available offer of extension services to farmers. This strongly constrains a demand driven extension approach | • Increasing financial resources at the lower levels where more work needs to be done; • Increasing coordination among extension providers to clearly communicate the available services to farmers; • Increasing the number of extension officers; • A stronger partnership with research actors and cooperatives is required for developing effective solutions to be easily implemented by smallholders; • Extension should also focus on women and youth engagement in agricultural activities; • Facilitating the uptake of water and soil conservation practices, as well as other relevant innovations; • Promoting diversification (particularly by discouraging maize monocropping) |

| National Agriculture Policy and National Agriculture Investment Plan | Improve efficiency and broaden business base of commercial activities of ADMARC | • Enable ADMARC, to play a facilitating role in the development of smallholder agriculture in Malawi • Enhanced efficiency and inclusiveness of agricultural markets and trade | • Map considered the implementation level for this measure particularly low. • This measure was considered potentially highly effective by the majority of MAP members. | • The current market structures are not well structured to facilitate profitable marketing of produce by farmers. For example, major markets such as Agricultural Development cooperation (ADMARC) do not have functional depots accessible to farmers • Delays in buying during harvest season due to the slow flow of financial resources lead farmers to sell their produce to other vendors below the floor price. | • ADMARC should be engaged in coordination mechanisms involving all VC actors; • ADMARC should be ready to buy farmers’ produce at the beginning of the harvest season; |

| National Agriculture Policy | Promote the use of contract farming, out-grower schemes and other appropriate value chain coordinating mechanisms for smallholder commercialisation | • Promote competitiveness of agriculture marketing value chains | • The implementation level for this instrument was considered low. • The measure is considered potentially highly effective by MAP members. | • Contract farming policies/regulations are commonly violated by companies • Contracts with farmers are not respected • Poor understanding of contracts’ terms by farmers. | • Clear guidelines are needed on how to formulate equitable contracts • Farmers should be supported in understanding contracts’ legal terms • Farmers should be supported in enforcing contracts when they are violated |

| National Agriculture Policy | Improve the procurement efficiencies of farm inputs to ensure timely delivery | • Enhance the use of farm inputs: • Enhance agricultural productivity and resilience to climate change | • The implementation level for this instrument was considered low. Data from the household survey indicate that only 16% of respondents have had access to subsidies, and only 23% use pesticides. The percentage of respondents using fertilisers raises instead to 43%. • The measure is considered potentially highly effective by MAP members. | • Difficult access to input subsidies • Input subsidies provision is affected by the slow formulation of the national budget of the country impeding the access to inputs before the planting season • In some cases, farmers receive and re-sell coupons to subsidise the price of fertiliser • Lack of sanction mechanisms against coupon resale • Lack of sanction mechanism against agro-dealers selling low quality inputs • Agro-dealers provide a limited range of agricultural inputs | • Farmer organisation should be involved by FISP to play an intermediation role in subsidies’ provision • The National Budget of the country should be known early by farmers accessing the inputs before the planting season • A monitoring system should be put in place to facilitate farmers in accessing subsidies and prevent the resale of coupons |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Branca, G.; Cacchiarelli, L.; D’Amico, V.; Dakishoni, L.; Lupafya, E.; Magalasi, M.; Perelli, C.; Sorrentino, A. Cereal-Legume Value Chain Analysis: A Case of Smallholder Production in Selected Areas of Malawi. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11121217

Branca G, Cacchiarelli L, D’Amico V, Dakishoni L, Lupafya E, Magalasi M, Perelli C, Sorrentino A. Cereal-Legume Value Chain Analysis: A Case of Smallholder Production in Selected Areas of Malawi. Agriculture. 2021; 11(12):1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11121217

Chicago/Turabian StyleBranca, Giacomo, Luca Cacchiarelli, Valentina D’Amico, Laifolo Dakishoni, Esther Lupafya, Mufunanji Magalasi, Chiara Perelli, and Alessandro Sorrentino. 2021. "Cereal-Legume Value Chain Analysis: A Case of Smallholder Production in Selected Areas of Malawi" Agriculture 11, no. 12: 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11121217

APA StyleBranca, G., Cacchiarelli, L., D’Amico, V., Dakishoni, L., Lupafya, E., Magalasi, M., Perelli, C., & Sorrentino, A. (2021). Cereal-Legume Value Chain Analysis: A Case of Smallholder Production in Selected Areas of Malawi. Agriculture, 11(12), 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11121217