Assessing the Transformative Potential of Food Banks: The Case Study of Magazzini Sociali (Italy)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Two Sides of the Food Paradox and Its Causes

3. The Response to the Food Paradox in Italy: The Food Banks System

4. The Transformative Potential of Food Redistribution Initiatives: A Conceptual Framework

4.1. The Theoretical Background

4.2. The PAHS Model

- Enabling replication of projects within the niche, bringing about aggregative changes through many small initiatives;

- Enabling constituent projects to grow in scale and attract more participants;

- Facilitating translation of niche ideas into mainstream settings.

5. Methodology

- A literature review phase, where the most appropriate questionnaire was selected and adapted to the needs of our case and the material for the creation of an analytical framework aimed at assessing the transformative potential of the initiative was detected;

- A phase dedicated to delivery of the first questionnaire (June 2020) and the first semi-structured interviews (August 2020);

- A writing and reflection phase: the case study was drafted according to the initial plan, then results were elaborated according to a SWOT analysis and discussed with the volunteers in a second semi-structured interview (September 2020) based on our analytical framework;

- Two final deep interviews to the president and vice president of the association in November 2020.

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. The Social Context

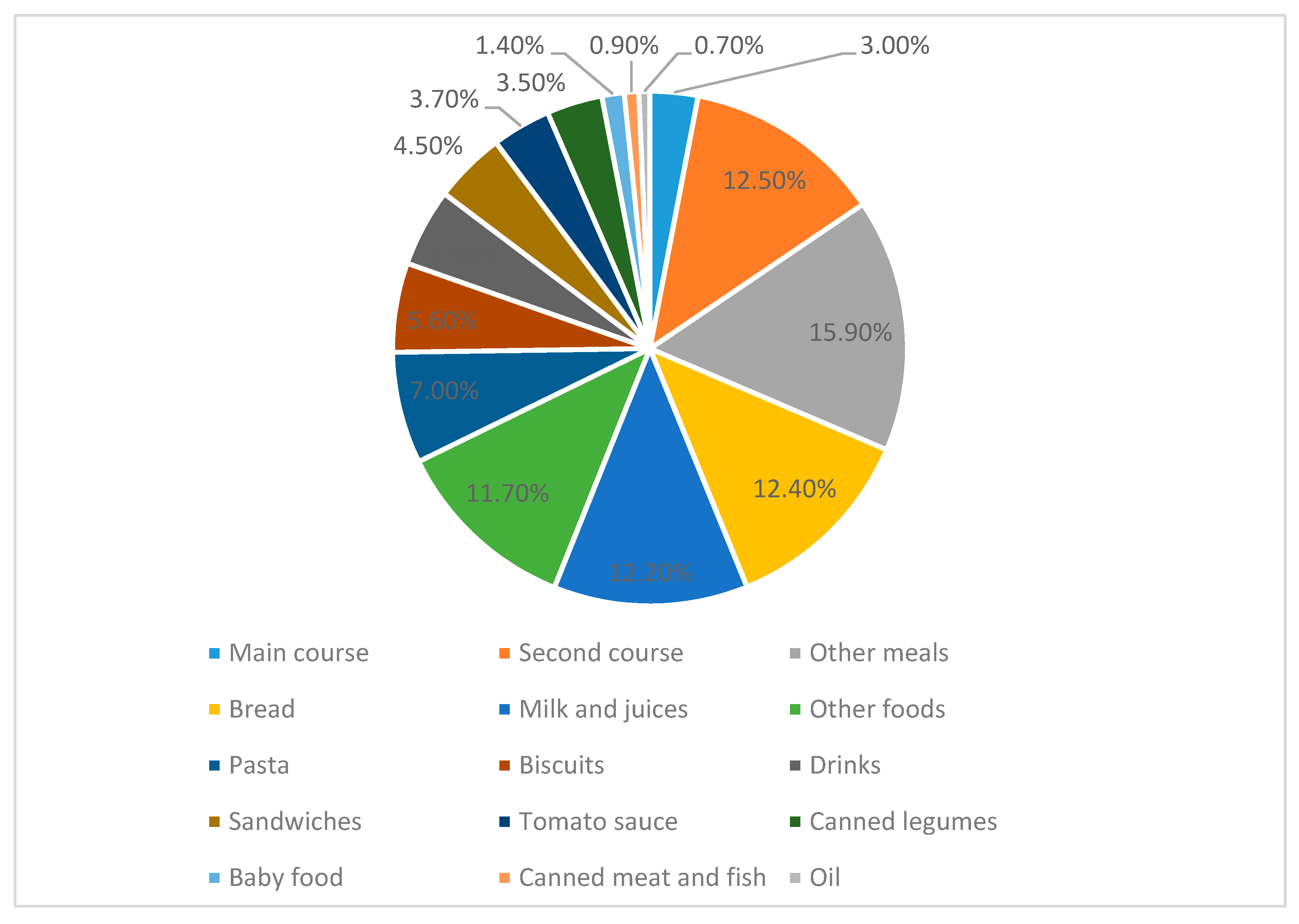

6.2. The Story and Activity of Magazzini Sociali

6.3. Interviews in SWOT Analysis According to the PAHS Model

6.4. Magazzini Sociali within the PAHS Theoretical Framework

6.4.1. Prefiguration

6.4.2. Autonomy

6.4.3. Hybridity

6.4.4. Scalability

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dowler, E.A.; O’Connor, D. Rights-based approaches to addressing food poverty and food insecurity in Ireland and UK. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Long, M.A.; Gonçalves, L.; Stretesky, P.B.; Defeyter, M.A. Food Insecurity in Advanced Capitalist Nations: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenmarck, A.; Jensen, C.; Quested, T.; Moates, G. Estimates of European Food Waste Levels. Fusions. 2016. Available online: https://www.eu.fusions.org/phocadownload/Publications/Estimates%20of%20European%20food%20waste%20levels.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Galli, F.; Cavicchi, A.; Brunori, G. Food waste reduction and food poverty alleviation: A system dynamics conceptual model. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campiglio, L.; Rovati, G. La Povertà Alimentare in Italia: Prima Indagine Quantitativa e Qualitativa; Guerini e Associate: Milano, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Riches, G.; Silvasti, T. First World Hunger Revisited: Food Charity or the Right to Food? 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, O.; Geiger, B.B. Did Food Insecurity rise across Europe after the 2008 Crisis? An analysis across welfare regimes. Soc. Policy Soc. 2016, 16, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Da Rold, C. A Proposito di Covid-19 e Disuguglianza: +40% di Assistiti dal Banco Alimentare, Il Sole 24Ore (Newspaper), 2020. Available online: https://www.infodata.ilsole24ore.com/2020/08/05/proposito-covid-19-disuguglianza-40-assistiti-dal-banco-alimentare/?refresh_ce=1 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Caplan, P. Big society or broken society? Food banks in the UK. Anthropol. Today 2016, 32, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Lozano, R.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; bin Ujang, Z. The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebinck, A.; Galli, F.; Arcuri, S.; Carroll, B.; O’Connor, D.; Oostindie, H. Capturing change in European food assistance practices: A transformative social innovation perspective. Local Environ. 2018, 23, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, S. Socio-ecological consequences of charitable food assistance in the affluent society: The German Tafel. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.O. Envisioning Real Utopias; Verso: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 394. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Liu, G.; Parfitt, J.; Liu, X.; Van Herpen, E.; Stenmarck, A.; O’Connor, C.; Östergren, K.; Cheng, S. Missing Food, Missing Data? A Critical Review of Global Food Losses and Food Waste Data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6618–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC Delegated Decision C. 3211 Final and Annex. Supplementing Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards a Common Methodology and Minimum Quality Requirements for the Uniform Measurement of Levels of Food Waste. 2019. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/3/2019/EN/C-2019–3211-F1-EN-MAIN-PART-1.PDF (accessed on 27 June 2019).

- Quested, T.E.; Parry, A.D.; Easteal, S.; Swannell, R. Food and drink waste from households in the UK. Nutr. Bull. 2011, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivupuro, H.K.; Hartikainen, H.; Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.M.; Heikintalo, N.; Reinikainen, A.; Jalkanen, L. Influence of socio-demographical, behavioural and attitudinal factors on the amount of avoidable food waste generated in Finnish households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, C.; Alboni, F.; Falasconi, L. Quantities, Determinants and Awareness of Households’ Food Waste in Italy: A Comparison between Diary and Questionnaires Quantities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herzberg, R.; Schmidt, T.G.; Schneider, F. Characteristics and Determinants of Domestic Food Waste: A Representative Diary Study across Germany. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschini, M.; Falasconi, L.; Alboni, F.; Cicatiello, C.; Nassivera, F.; Giordano, C.; Arcella, G.; Franco, S.; Troiano, S.; Marangon, F.; et al. Lo Spreco Alimentare a Scuola Indagine Nazionale Sugli Sprechi Nelle Mense Scolastiche e Proposta di Una Metodologia di Rilevamento. Ministero DELL’Ambiente e Della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare—Direzione Generale Per i Rifiuti e L’inquinamento, Progetto Reduce, ISBN 978-88-97549-48-1. Available online: https://www.sprecozero.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Report-AR3-%E2%80%93-Scuole.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Cicatiello, C.; Franco, S.; Pancino, B.; Blasi, E.; Falasconi, L. The dark side of retail food waste: Evidences from in-store data. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicatiello, C.; Franco, S. Disclosure and assessment of unrecorded food waste at retail stores. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 Amending Directive 2008/98/EC on Waste (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32018L0851&from=EN (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions (2020). A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0381&from=EN (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Atti Parlamentari XVII Legislatu—Disegni Di Legge E Relazioni—Documenti—Doc. CCXXIV, N. 1 “Le Attività Successive ra All’emanazione del Programma Nazionale di Prevenzione dei Rifiuti: Il Piano Nazionale di Prevenzione Degli Sprechi Alimentari (PINPAS)”, Relazione al Parlamento. pp. 37–48. Available online: https://www.camera.it/_dati/leg17/lavori/documentiparlamentari/indiceetesti/224/001_RS/00000003.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Gazzetta Ufficiale, Legge 19 Agosto 2016, n. 166. Disposizioni Concernenti la Donazione e la Distribuzione di Prodotti Alimentari e Farmaceutici a fi ni di Solidarietà Sociale e per la Limitazione Degli Sprechi. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2016/08/30/202/sg/pdf#:~:text=ALTRI%20ATTI%20NORMATIVI-,LEGGE%2019%20agosto%202016%20%2C%20n.,per%20la%20limitazione%20degli%20sprechi (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Giordano, C.; Falasconi, L.; Cicatiello, C.; Pancino, B. The role of food waste hierarchy in addressing policy and research: A comparative analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Blaming the consumer–once again: The social and material contexts of everyday food waste practices in some English households. Crit. Public Health 2011, 21, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowler, E. Food and poverty in Britain: Rights and responsibilities. Soc. Policy Adm. 2002, 36, 698–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat News Release 158/2019-16 October 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/10163468/3-16102019-CP-EN.pdf/edc3178f-ae3e-9973-f147-b839ee522578 (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Loopstra, R.; Tarasuk, V. Severity of household food insecurity is sensitive to change in household income and employment status among low-income families. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 1316–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loopstra, R.; Reeves, A.; Stuckler, D. Rising food insecurity in Europe. Lancet 2015, 385, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEBA, European Food Banks in a post COVID-19 Europe, July 2020. Available online: https://lp.eurofoodbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/FEBA_Report_Survey_COVID_July2020.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Istat, Rapporto Povertà 2019, 2020. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2020/06/REPORT_POVERTA_2019.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Cannari, L.; D’Alessio, G. La Disuguaglianza Della Ricchezza in Italia: Ricostruzione dei Dati 1968-75 e Confronto Con Quelli Recenti; Occasional Paper; Questioni di Economia e Finanza; 2018; ISSN 1972-6643. Available online: https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/qef/2018-0428/index.html (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- World Inequality Database, Country Index, Italy. Available online: https://wid.world/country/italy/ (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Istat (b), Rapporti Tematici 2020. Available online: https://www.istat.it/storage/rapporti-tematici/territorio2020/capitolo_1.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Eurostat, COVID 19 Dataset. Item GDP and Main Components (Output, Expenditure and Income). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/covid-19/data (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Thyberg, K.L.; Tonjes, D.J. Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, P. A food regime genealogy. J. Peasant Stud. 2009, 36, 139–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam Bliss. The Case for Studying Non-Market Food Systems. Sustain. J. Rec. 2019, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Neo-Liberalism as Creative Destruction. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2006, 88, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.R.; Edwards, F.; Marovelli, B.; Morrow, O.; Rut, M.; Weymes, M. Making visible: Interrogating the performance of food sharing across 100 urban areas. Geoforum 2017, 86, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazerghi, C.; McKay, F.H.; Dunn, M. The Role of Food Banks in Addressing Food Insecurity: A Systematic Review. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handforth, B.; Hennink, M.; Schwartz, M.B. A qualitative study of nutrition-based initiatives at selected food banks in the feeding America network. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, I.; Guedes, T.; Rama, P.; Ramnos, J.; Tchemisova, T. Modelling the problem of food distribution by the Portuguese food banks. Int. J. Math. Model. Numer. Optim. 2011, 2, 313–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Torre, P.; Coque, J. How is a food bank managed? Different profiles in Spain. Agric. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A. The adaptive change of the Italian Food Bank foundation: A case study. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1446–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrone, P.; Melacini, M.; Perego, A.; Sert, S. Reducing food waste in food manufacturing companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, E.M. Combining Social Justice and Sustainability for Food Security. In For Hunger-Proof Cities. Sustainable Urban Food Systems; Koc, M., MacRae, R., Luc, J.A.M., Jennifer, Eds.; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Messner, R.; Richards, C.; Johnson, H. The “Prevention Paradox”: Food waste prevention and the quandary of systemic surplus production. Agric. Hum. Values 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riches, G. Thinking and acting outside the charitable food box: Hunger and the right to food in rich societies. Dev. Pract. 2011, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcuri, S. Food poverty, food waste and the consensus frame on charitable food redistribution in Italy. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambie-Mumford, H. Every Town should have one’: Emergency Food Banking in the UK. J. Soc. Policy 2013, 42, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, M.; Costantino, M. A Social Innovation Model for Reducing Food Waste: The Case Study of an Italian Non-Profit Organization. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Environ. Politics 2007, 16, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, C.A.; Biddulph, R. Capturing Waste or Capturing Innovation? Comparing Self-Organising Potentials of Surplus Food Redistribution Initiatives to Prevent Food Waste. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, O. Community Self-Organizing and the Urban Food Commons in Berlin and New York. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, A.D. Beyond Alternative: Exploring the Potential for Autonomous Food Spaces. Antipode 2013, 45, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Haxeltine, A. Growing Grassroots Innovations: Exploring the Role of Community-Based Initiatives in Governing Sustainable Energy Transitions. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2012, 30, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rut, M.; Davies, A.R.; Ng, H. Participating in food waste transitions: Exploring surplus food redistribution in Singapore through the ecologies of participation framework. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2021, 23, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, L. Rethinking Prefiguration: Alternatives, Micropolitics and Goals in Social Movements. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2015, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleyers, G. Local food movements: From prefigurative activism to social innovations. Interface A J. Soc. Mov. 2017, 9, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. Theorizing Agri-Food Economies. Agriculture 2016, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vivero-Pol, J.-L.; Ferrando, T.; De Schutter, O.; Mattei, U. The food commons are coming …. In Routledge Handbook of Food as A Commons; Vivero-Pol, J.L., Ferrando, T., de Schutter, O., Mattei, U., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-138-06262-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, P.; Agyeman, J. Urban food sharing and the emerging Boston food solidarity economy. Geoforum 2019, 99, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulug, C.; Trell, E.-M. ‘It’s not really about the food, it’s also about food’: Urban collective action, the community economy and autonomous food systems at the Groningen Free Café. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2020, 12, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collective Actions of Solidarity against Food Insecurity. The Impact in Terms of Capabilities; VS Verlag Für Sozialwissenschaften, 2020; Volume XVI, p. 92. ISBN 978-3-658-31374-6. Available online: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783658313746 (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Papadaki, M.; Kalogeraki, S. Exploring Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) During the Greek economic crisis. Partecip. E Confl. 2018, 11, 38–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rakopoulos, T. Solidarity: The egalitarian tensions of a bridge-concept. Soc. Anthropol. 2016, 24, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Okely, J. Anthropological Practice: Fieldwork and the Ethnographic Method; Berg: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT Database, Basilicata Region. 2020. Available online: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?QueryId=18564 (accessed on 4 October 2020).

- Mininni, M.; Bisciglia, S. Sistemi del cibo nelle economie urbane e periurbane. In Quarto Rapporto Sulle Città 2017 “Il Governo Debole Delle Economie Urbane” Il Mulino, Bologna, Italy; D’Albergo, E., Di Leo, D., Viesti, G., Eds.; 2019; pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam Robert, D. Bowling Alone by “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital”. J. Democr. 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. The Role of Social Capital in Financial Development. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 526–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piras, S.; Pancotto, F.; Righi, S.; Vittuari, M.; Setti, M. Community social capital and status: The social dilemma of food waste. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 183, 106954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mininni, M.; Santarsiero, V. Food Planning and Foodscape. Matera as a Laboratory of Urban Food Policy AESOP Sustainable Food Planning Workshop 2018, towards sustainable City Region Food Systems NewDist 2/2018; pp. 32–36 special issue AESOP SUSTAINABLE FOOD.

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge Regionale 11 agosto 2015, n. 26 recante “Contrasto al disagio sociale mediante l’utilizzo di eccedenze alimentari e non: Approvazione linee guida attuative. Regional law, Basilicata. Available online: http://www.edizionieuropee.it/LAW/HTML/205/ba5_02_085.html (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Vaillancourt, Y. Social economy in the co-construction of public policy. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2009, 80, 275–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G.; Rossi, A.; Malandrin, V. Co-producing Transition: Innovation Processes in Farms Adhering to Solidarity-based Purchase Groups (GAS) in Tuscany, Italy. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2011, 18, 28–53. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano, P.R.; Forno, F. Political Consumerism and New Forms of Political Participation: The Gruppi di Acquisto Solidale in Italy. Ann. AAPSS 2012, 644, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strengths | Weaknesses | |

|---|---|---|

| Prefiguration |

|

|

| Autonomy |

|

|

| Hybridization |

|

|

| Scalability |

|

|

| Opportunities | Threats | |

|---|---|---|

| Prefiguration |

|

|

| Autonomy |

|

|

| Hybridization |

|

|

| Scalability |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berti, G.; Giordano, C.; Mininni, M. Assessing the Transformative Potential of Food Banks: The Case Study of Magazzini Sociali (Italy). Agriculture 2021, 11, 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11030249

Berti G, Giordano C, Mininni M. Assessing the Transformative Potential of Food Banks: The Case Study of Magazzini Sociali (Italy). Agriculture. 2021; 11(3):249. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11030249

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerti, Giaime, Claudia Giordano, and Mariavaleria Mininni. 2021. "Assessing the Transformative Potential of Food Banks: The Case Study of Magazzini Sociali (Italy)" Agriculture 11, no. 3: 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11030249

APA StyleBerti, G., Giordano, C., & Mininni, M. (2021). Assessing the Transformative Potential of Food Banks: The Case Study of Magazzini Sociali (Italy). Agriculture, 11(3), 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11030249