The Impact of Livelihood Risk on Farmers of Different Poverty Types: Based on the Study of Typical Areas in Sichuan Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Development

2.1. Poverty Types

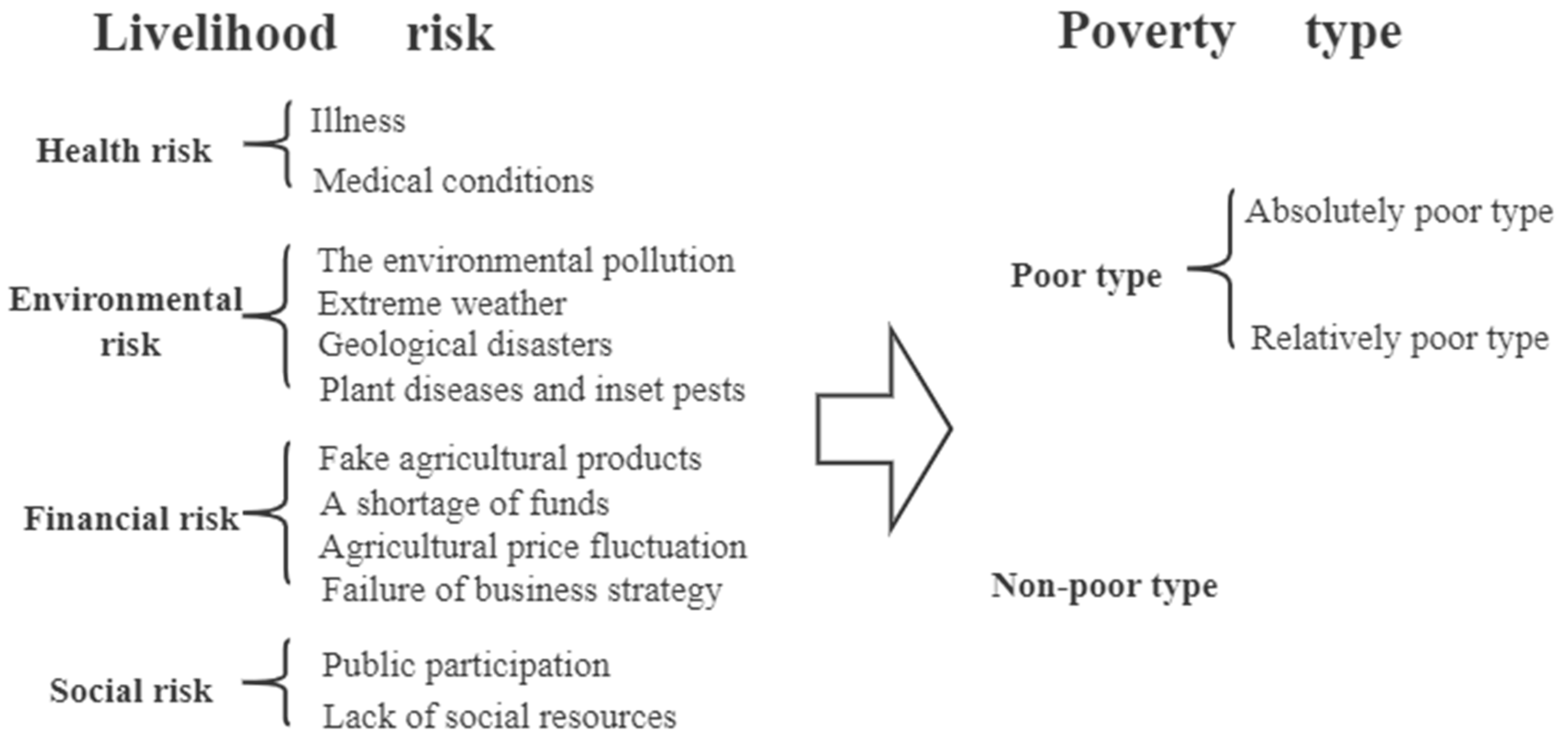

2.2. Livelihood Risk

2.3. Relative Poverty Line

2.4. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

3. Materials and Methods

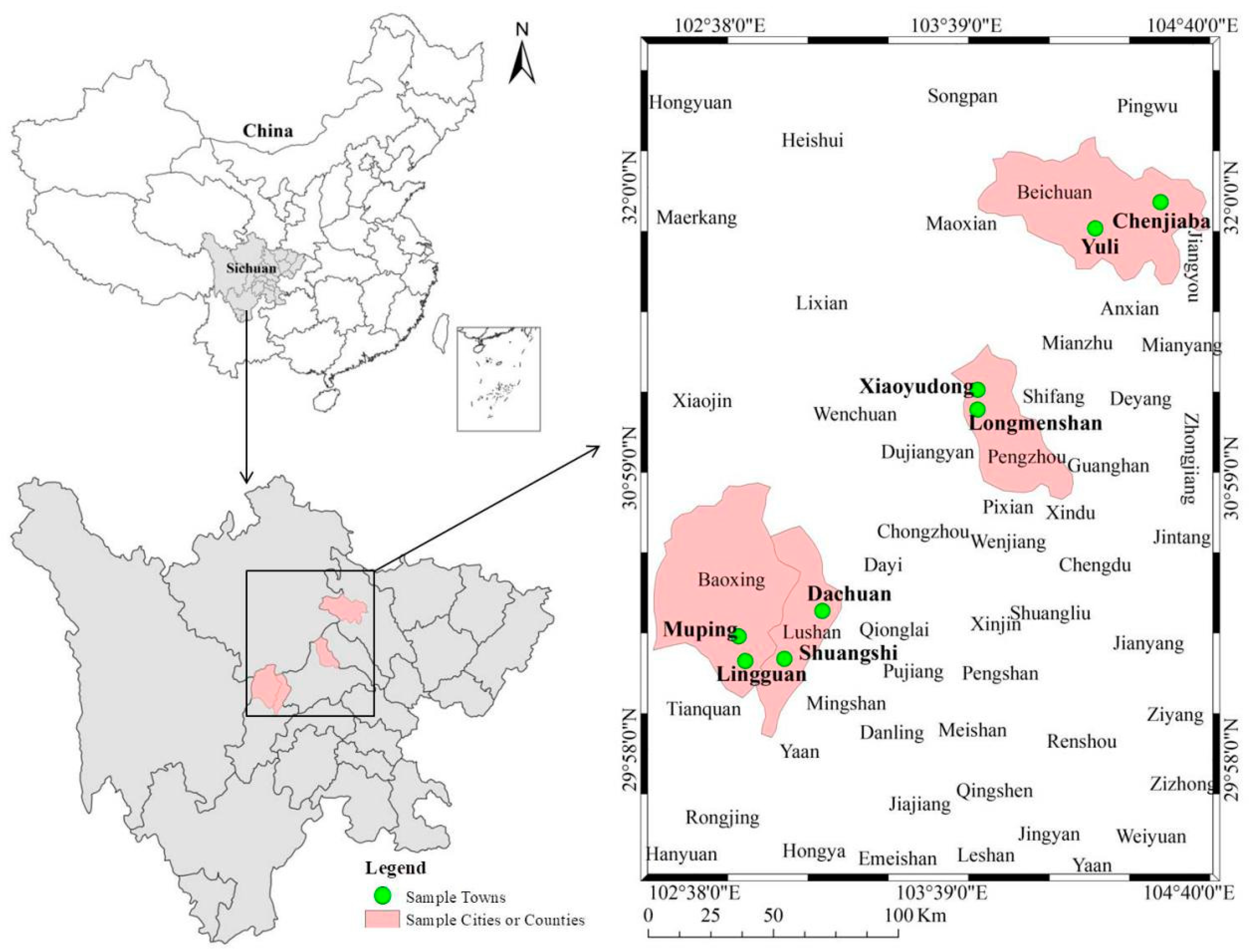

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Livelihood Risk

3.2.2. Poverty Type

3.2.3. Entropy Method

3.2.4. Analytic Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.2. Model Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Among the four types of livelihood risk, the environmental risk had the highest comprehensive score (0.40), followed by financial risk (0.33), health risk (0.17), and social risk (0.10).

- (2)

- Among the three types of poverty in which farmers live, absolutely poor farmers have the largest number (177 households, accounting for 54.1%), and relatively poor farmers have the least number (41 households, accounting for 12.6%).

- (3)

- Farmers of different poverty types are impacted by different levels of livelihood risks. Specifically, compared with absolutely poor farmers, relatively poor farmers are more severely impacted by social risks, but the impact of health risks, environmental risks and financial risks is not significant. Impacted by social risks, relatively poor farmers are more seriously impacted by public affairs and social security status, especially public affairs. Compared with the non-poor farmers, the relatively poor farmers are not affected by the four livelihood risks.

- (1)

- The government should consolidate the continued stability of agricultural and rural financial investment to prevent non-poor households from falling into poverty due to financial risks. The research results show that non-poor farmers are more severely impacted by financial risks. The government should increase the intensity and capital investment of welfare policies such as critical illness relief, industrial poverty alleviation, and public welfare posts, and help non-poor farmers to build a strong livelihood capital base and improve their livelihood capabilities through “blood-making” methods.

- (2)

- The government should expand the social resources of farmers through poverty alleviation projects. The research results show that non-poor farmers are more severely impacted by social risks. The government should provide farmers with more market information, market sales channels, and financial and physical capital support, and encourage non-poor farmers to learn to independently develop markets and establish social resources.

- (1)

- Future research needs to design a more comprehensive indicator system to measure the difference in livelihood risk between different types of poverty-stricken households. It is necessary to consider the endogenous problem of variable selection, and at the same time pay more attention to the impact of various livelihood risk variables on the farmers’ economy, select the economic benefits of different types of poor farmers as the evaluation object, and make a reasonable efficiency evaluation.

- (2)

- The impact of different types of poverty-stricken households on industries and the economy is comprehensive and complex, and it is necessary to conduct in-depth research on them from the perspective of more participants. Participants not only involve farmers of different types of poverty, but also governments, enterprises and various intermediary organizations, so they need to be fully considered in future research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, W. Research on the Multidimensional Poverty Dynamics of Rural Households. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, Wuhan, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Millennium Development Goals Report 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2019; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.L. Research on Sustainable Livelihoods of Relatively Poor Families in Rural Areas of Southwest Zhejiang. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang Agriculture and Forestry University, Zhejiang, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2021; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fritzell, J.; Rehnberg, J.; Bacchus Hertzman, J.; Blomgren, J. Absolute or relative? A comparative analysis of the relationship between poverty and mortality. Int. J. Public Health 2014, 60, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reutlinger, S. Malnutrition: A poverty or a food problem? World Dev. 1997, 5, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwittay, A.F. Making poverty into a financial problem: From global poverty lines to KIVA.ORG. J. Int. Dev. 2013, 26, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, G. The credit crunch: Housing bubbles, globalisation and the worldwide economic crisis. Sov. Phys. Dokl. 2009, 17, 317–319. [Google Scholar]

- Piccato, P.; Fische, B. A Poverty of Rights: Citizenship and Inequality in Twentieth-Century Rio de Janeiro; University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 115, pp. 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.W. Study on the Harm of Poverty. Gansu Agric. 2016, 1, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, L.M. Unequal democracy: The political economy of the new gilded age. Econ. Books 2016, 73, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R.G.; Pickett, K. The Spirit Level: Why Equality Is Better for Everyone; Penguin book: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Conradt, E.; Measelle, J.; Ablow, J.C. Poverty, problem behavior, and promise. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klebanov, P.K.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Duncan, G.J. Does neighborhood and family poverty affect mothers’ parenting, mental health, and social support? J. Marriage Fam. 1994, 56, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, T.; Brooks-Gunn, J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 309–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Peng, L.; Liu, S.; Su, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, T. Influences of migrant work income on the poverty vulnerability disaster threatened area: A case study of the Three Gorges Reservoir area, China. Int. J. Disast. Risk Reduct. 2017, 22, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S. Weakly relative poverty. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2011, 93, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riungu, G.K. Book review: Holden, Andrew. 2013: Tourism, Poverty and Development. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2015, 15, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.W.; Xia, T. China’s Poverty Alleviation Strategy and the Delineation of Relative Poverty Line after 2020—Analysis Based on Theory, Policy and Data. China Rural Econ. 2019, 10, 98–113. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B. Statistical inference for poverty measures with relative poverty lines. J. Econom. 2001, 101, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.X.; Ye, J.Y. The role of social capital in alleviating rural poverty: Literature review and research prospects. South. Econ. 2014, 7, 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.G.; Liu, M.Y. From Absolute Poverty to Relative Poverty: Theoretical Relationship, Strategic Transformation and Policy Focus. J. South China Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 2020, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Report 1990; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, P. Introduction: Concepts of Poverty and Deprivation. J. Soc. Policy 1979, 15, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Barney, J.B.; Newman, A.M.B. The poverty problem and the industrialization solution. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Deng, X.; Guo, S.; Liu, S. Sensitivity of livelihood strategy to livelihood capital: An empirical investigation using nationally representative survey data from rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 144, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.L.; Wu, J. Research on farmers’ livelihood risks: A case study of Le’an county, Jiangxi. J. Guangxi Univ. Natl. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2007, 2007, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F. Analysis of the impact of farmers’ livelihood risks on their livelihood capital—Taking Shiyang River Basin as an example. Agric. Technol. Econ. 2017, 2017, 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Addison, J.; Brown, C. A multi-scaled analysis of the effect of climate, commodity prices and risk on the livelihoods of Mongolian pastoralists. J. Arid Environ. 2014, 109, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, C.; Nzokou, P.; Mbow, C. Farmer Livelihood Strategies and Attitudes in Response to Climate Change in Agroforestry Systems in Kedougou, Senegal. Environ. Manag. 2020, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I.; Wolmer, W. Introduction: Livelihoods in crisis: Challenges for rural development in South Africa. IDS Bull. 2003, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Shang, H.Y. The impact of farmers’ livelihood capital on their risk response strategies: A case study of Zhangye City in the Heihe River Basin. China Rural Econ. 2012, 2012, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.G.; Su, S.P. The livelihood risks and coping strategies of farmers under the impact of a major epidemic—A case study based on mountainous areas in Fujian. J. Fujian Agric. For. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, W.; Deng, X.; Ma, Z.; Yong, Z.; Qing, C. Information credibility, disaster risk perception and evacuation willingness of rural households in China. Nat. Hazards 2020, 103, 2865–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.Y.; Guo, S.L.; Deng, X.; Xu, D.D. Livelihood risk and adaptation strategies of farmers in earthquake hazard threatened areas: Evidence from sichuan province, China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 53, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Xu, D.D.; Wang, X.X. Vulnerability of rural household livelihood to climate variability and adaptive strategies in landslide-threatened western mountainous regions of the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China. Clim. Dev. 2019, 11, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Feng, H.X. China’s multidimensional relative poverty standards after 2020: International experience and policy orientation. China’s Rural Econ. 2020, 2020, 2–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, H. Relative poverty and anti-poverty policy system. People’s Forum 2019, 2019, 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, S.M.S. Sustainable Tourism Development & Poverty Alleviation; Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J.; Shi, L. Three Poverties in Urban China. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2006, 10, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Li, S.Z. Analysis of poverty types and influencing factors of immigrant relocated farmers—Sampling survey based on Ankang in southern Shaanxi. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2015, 6, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwosri; Sunaryono, D.; Akbar, R.J.; Setiyawan, R.D. Poverty classification using Analytic Hierarchy Process and k-means clustering. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Information & Communication Technology and Systems (ICTS), Surabaya, Indonesia, 12–12 October 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Song, N.N.; Ma, J.; Luo, W.C. Risk response strategies of different capital-deficient farmers—Taking the Qinba Mountains in southern Shaanxi as an example. J. China Agric. Univ. 2020, 25, 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, M.; Wu, M.; Alam, G.; Shouse, R.C. Life in riverine islands in bangladesh: Local adaptation strategies of climate vulnerable riverine island dwellers for livelihood resilience. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.J.; Tong, X.H.; Wan, X.Y.; He, R.; Kuang, F.; Ning, J. Farmers’ risk aversion, loss aversion and climate change adaptation strategies in Wushen Banner, China. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Nguyen, H.H.; Van Ta, H.; Van Nguyen, H.; Pham, T.A.; Nguyen, B.T.; Pham, T.T.; Tang, N.T.T.; Hens, L. Rural livelihood diversification of Dzao farmers in response to unpredictable risks associated with agriculture in Vietnamese Northern Mountains today. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 1, 5387–5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.B. Risk and vulnerability of farmers: An analytical framework and the experience of poor areas. Agric. Econ. Issues 2005, 2005, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Zhao, H.L.; Liu, C.F. The livelihood risks and coping strategies of farmers in the lower reaches of Shiyang River—Taking Minqin Oasis as an example. Geogr. Res. 2015, 34, 922–932. [Google Scholar]

- Dercons. Assessing Vulnerability; Publication of the Jesus College and CSAE: Oxford, UK, 2001; Volume 2, pp. 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, C.H.; Huby, M.; Kiwasila, H.; Lovett, J.C. Local perceptions of risk to livelihood in semi-arid Tanzania. J. Environ. Manag. 2003, 68, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Saikia, U.; Hay, I. Impact of perceived livelihood risk on livelihood strategies: A case study in Shiyang River Basin, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.W. A review of researches on the concept and types of poverty. J. Econ. 2006, 2006, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, Z.H.; Yang, Y.Y. Summary of Research on Poverty Line. Econ. Theory Econ. Manag. 2012, 2012, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, M.S.; Townsend, P. Poverty in the United Kingdom: A Surrey of Household Resources and Standards of Living. By Townsend Peter. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979. Pp. 1216. $37.50, cloth; $15.95, paper.). Am. Political Sci. Assoc. 1981, 75, 257–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Application of the Martin method in the study of rural poverty standards in China. J. Shenyang Univ. 1996, 4, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Report 2000/2001 Attacking Poverty; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F.; Saikia, U.; Hay, I. Relationships between livelihood risks and livelihood capitals: A case study in Shiyang River Basin, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Gai, Z.Y. Review and prospect of research on economic behavior of poor farmers under the impact of health risks. Inn. Mong. Soc. Sci. 2020, 41, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.W.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.R. Medical insurance, poverty and family medical consumption—based on panel fixed effects Tobit Model estimation. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2012, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, F. Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. J. Dev. Stud. 1998, 35, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Shuai, C.M.; Wang, J.; Li, W.J.; Liu, Y. Review of research on the impact of ecological environment and disasters on poverty. Resour. Sci. 2018, 40, 676–697. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M. Research on the risk sharing mechanism in the process of agricultural scale operation. Rural Econ. Technol. 2019, 30, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Tsegaye, D.; Vedeld, P.; Moe, S.R. Pastoralists and livelihoods: A case study from northern Afar, Ethiopia. J. Arid Environ. 2013, 91, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiling, L.I.; Haixia, M.A.; Yang, R. Influence of cotton farmer’s livelihood capitals on livelihood strategy—Based on the survey data of Manas and Awat counties, Xinjiang. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2017, 31, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, B. An empirical study on the willingness of poverty alleviation and relocation of poor households in Luliang Mountain Area—Taking Shenchi County and Wuzhai County as examples. Shanxi Agric. Econ. 2019, 2019, 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shameem, M.I.M.; Momtaz, S.; Rauscher, R. Vulnerability of rural livelihoods to multiple stressors: A case study from the southwest coastal region of Bangladesh. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 102, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peria, A.S.; Pulhin, J.M.; Tapia, M.A.; Peria, A.; Predo, C., Jr.; Peras, R.J.; Evangelista, R.J.; Lasco, R.; Pulhin, F. Knowledge, risk attitudes and perceptions on extreme weather events of smallholder farmers in ligao city, albay, bicol, philippines. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2016, 2016, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; He, J.; Liu, Q.X. The status quo of rural human settlements in poverty-stricken areas of Yunnan and suggestions for improvement. Guide J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 39, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.D. Research on the Dynamic Relationship between the Price Fluctuation of Agricultural Products in My Country and the Increase of Farmers’ Income. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moav, O.; Neeman, Z. Saving Rates and Poverty: The Role of Conspicuous Consumption and Human Capital. Econ. J. 2012, 122, 933–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longpichai, O.; Perret, S.R.; Shivakoti, G.P. Role of Livelihood Capital in Shaping the Farming Strategies and Outcomes of Smallholder Rubber Producers in Southern Thailand. Outlook Agric. 2012, 41, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, X.P.; Wang, S.G. The impact of agricultural product price changes on the income of farmers in poor areas. China Rural Econ. 2003, 2003, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.B.; Yan, Y.P. Research on the Obstacles and Countermeasures of Farmers’ Participation in Agricultural Products Futures Market in Henan Province. Farm Econ. Manag. 2020, 2020, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Feder, G.; Nishio, A. The benefits of land registration and titling: Economic and social perspectives. Land Use Policy 1998, 15, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Pouliot, M.; Walelign, S.Z. Livelihood Strategies and Dynamics in Rural Cambodia. World Dev. 2017, 97, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.P.; Pabuayon, I.M. Risk perceptions, attitudes, and influential factors of rainfed lowland rice farmers in Ilocos Norte, Philippines. Asian J. Agric. Dev. 2011, 08, 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.X. Governance of Farmers’ Response to Rural Social Risks—Based on the Analysis Perspective of Feasible Ability. J. Sichuan Univ. Sci. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2013, 28, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Colchester, M.; Lohmann, L. The Struggle for Land and the Fate of the Forests; World Rainforest Movement: Penang, Malaysia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, A.; Newman, L. Social capital: A necessary and sufficient condition for sustainable community development? Community Dev. J. 2008, 45, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasie, T.; Agrandio, A.; Adgo, E.; Garcia, I. Household Resilience to Food Insecurity: Shock Exposure, Livelihood Strategies and Risk Response Options: The case of Tach-Gayint District 2017, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Jaume I, Castelló, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.F.; Ma, Z.X.; Guo, S.L.; Deng, X.; Xu, D.D. Livelihood capital, evacuation and relocation willingness of residents in earthquakestricken areas of rural China. Safety Sci. 2021, 141, 105350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.F.; Guo, S.L.; Deng, X.; Xu, D.D. Livelihood resilience and strategies of rural residents of earthquake-threatened areas in Sichuan Province, China. Nat. Hazards 2021, 106, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.X.; Guo, S.L.; Deng, X.; Xu, D.D. Community resilience and resident’s disaster preparedness: Evidence from China’s earthquake-stricken areas. Nat. Hazards 2021, 108, 567–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, C.; Guo, S.L.; Deng, X.; Xu, D.D. Farmers’ Disaster Preparedness and Quality of Life in Earthquake-prone Areas: The Mediating Role of Risk Perception. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 59, 102525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.M.; He, J.; Yong, Z.L.; Deng, X.; Xu, D.D. Disaster information acquisition by residents of China’s earthquake-stricken areas. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.D.; Liu, E.L.; Wang, X.X.; Tang, H.; Liu, S.Q. Rural households’ livelihood capital, risk perception, and willingness to purchase earthquake disaster insurance: Evidence from southwestern China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Risk Dimension | Risk Variable | Variable Definition and Description | Mean | Standard Deviation | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health risk | Risk of illness | Whether you have a genetic disease or a serious disease (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.054 |

| External environment | Whether suffering from livestock plague, dysentery or diseases caused by major industrial pollution (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.033 | |

| Medical condition | Whether the medical system of the village health center is perfect (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.080 | |

| Environmental risk | Extreme weather | Whether extreme weather (such as heavy rainfall, freezing) has an impact on production and life (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.70 | 0.46 | 0.119 |

| Geological disaster | Whether geological disasters (such as earthquakes, landslides and mudslides) have an impact on production and life (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.152 | |

| Pests and diseases | Have you encountered the impact of plant diseases and insect pests (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.074 | |

| Water shortage | Whether water resources can meet the basic needs of production and life (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.94 | 0.23 | 0.030 | |

| Soil erosion | Degree of soil erosion (Very not serious = 1, Not serious = 2, General = 3, Serious = 4, Very serious = 5) | 2.83 | 1.36 | 0.027 | |

| Financial risk | Agricultural product price fluctuations | Whether agricultural production has been impacted by price fluctuations of agricultural products (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.051 |

| Fake agricultural products | Have you ever encountered fake agricultural products (such as fake pesticides, fake fertilizers) in agricultural production (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.038 | |

| Shortage of funds | Is there a lack of funds to expand the scale of agricultural production (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.107 | |

| Financing conditions | Is it difficult to obtain bank loans and financing (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.088 | |

| Business strategy decision | Whether there are mistakes in business strategy decision-making that bring losses to family economy (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.043 | |

| Social risk | Public affairs | Have you participated in the village public affairs decision-making (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.77 | 0.42 | 0.044 |

| Social security status | Whether the lack of basic security (pension, medical insurance, etc.) leads to poor livelihood (No = 0, Yes = 1) | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.060 |

| Poverty Type | Standard |

|---|---|

| Absolutely poor type | <3535 yuan/person·year |

| relatively poor type | 3535–7380.6 yuan/person·year |

| non-poor type | >7380.6 yuan/person·year |

| Types of Poverty | |

|---|---|

| Health risk | 3.058 |

| (1.38) | |

| Environmental risk | 1.298 |

| (1.26) | |

| Financial risk | 1.916 |

| (1.37) | |

| Social risk | 10.66 *** |

| (3.34) | |

| cut1_cons | 1.801 *** |

| (4.93) | |

| cut2_cons | 2.363 *** |

| (6.33) | |

| Wald chi2 (4) | 24.63 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0001 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0370 |

| Absolutely Poor Type | Non-Poor Type | |

|---|---|---|

| Health risk | −0.666 | 3.397 |

| (−0.18) | (0.88) | |

| Environmental risk | −0.833 | 0.643 |

| (−0.53) | (0.40) | |

| Financial risk | −1.328 | 1.036 |

| (−0.63) | (0.47) | |

| Social risk | −17.41 *** | −6.775 |

| (−3.01) | (−1.11) | |

| Constant | 3.185 *** | 0.863 |

| (4.69) | (1.20) | |

| LR chi2 (8) | 28.05 | |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0005 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0447 | |

| Types of Poverty | |

|---|---|

| Public affairs | 28.93 *** |

| (4.19) | |

| Social security status | 5.839 |

| (1.52) | |

| cut1_cons | 1.407 *** |

| (4.58) | |

| cut2_cons | 1.967 *** |

| (6.15) | |

| Wald chi2 (4) | 21.02 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0371 |

| Absolutely Poor Type | Non-Poor Type | |

|---|---|---|

| Public affairs | −27.88 ** | 2.651 |

| (−2.43) | (0.21) | |

| Social security status | −13.98 ** | −8.380 |

| (−2.12) | (−1.22) | |

| Constant | 2.997 *** | 1.232 ** |

| (5.41) | (2.01) | |

| LR chi2 (4) | 26.72 | |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0426 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, X.; Fu, Z.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. The Impact of Livelihood Risk on Farmers of Different Poverty Types: Based on the Study of Typical Areas in Sichuan Province. Agriculture 2021, 11, 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11080768

Zeng X, Fu Z, Deng X, Xu D. The Impact of Livelihood Risk on Farmers of Different Poverty Types: Based on the Study of Typical Areas in Sichuan Province. Agriculture. 2021; 11(8):768. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11080768

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Xuanye, Zhuoying Fu, Xin Deng, and Dingde Xu. 2021. "The Impact of Livelihood Risk on Farmers of Different Poverty Types: Based on the Study of Typical Areas in Sichuan Province" Agriculture 11, no. 8: 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11080768

APA StyleZeng, X., Fu, Z., Deng, X., & Xu, D. (2021). The Impact of Livelihood Risk on Farmers of Different Poverty Types: Based on the Study of Typical Areas in Sichuan Province. Agriculture, 11(8), 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11080768