This section examines and discusses the results of the study under three heads: (i) formal institutions and the meso-institutions in the regions, (ii) comparing the degree of translation/implementation/monitoring of the rules by meso-institutions and perceived differences in the performance of the regions, and (iii) effect of meso-institutions on milk production in the western border of RS.

3.1. Formal Institutions and the Meso-Institutions in the Regions

The formal institutions (macro-institutions) that regulate milk production in Brazil are Normative Instruction No. 76 [

13] and Normative Instruction No. 77 [

14], both published on 26 November 2018, to take effect on 30 May 2019. The first standard defines the identity and quality characteristics for raw refrigerated milk produced on farms and intended for processing at milk and milk-products plants that are subject to official inspection. The second standard establishes the regulations regarding the procedures to be followed in milk production. The new regulations improve upon MAPA’s Normative Instruction No. 51 of 2002 and No. 62 of 2011, which establish the qualifications and professionalism of all participants in the dairy sector.

Normative Instruction No. 76 essentially defines the quality standards for raw milk to be maintained during its production, while Normative Instruction No. 77 lays down a series of regulations for the milk supply chain and identifies the institutions responsible for enforcement and monitoring of the rules. One of the severest rules imposed on the milk producers is that if laboratory analysis of milk showed a continuous digression from the established quality standards over three months, the dairy would suspend the collection of milk from the defaulting producer.

Another indirect restriction that attracts sanctions concerns the control of the use of preservatives and antimicrobials by milk producers. In Brazil [

14], the dairy industry, upon detecting non-compliance of analyzed milk delivered by a truck, must send samples of that milk for evaluation, and the milk producer must be notified of the anomaly so that he can take the necessary corrective measures.

In their self-reports, the respondents criticized some of the restrictions imposed by the standards. For PS2, “the required standard for the somatic cell count (SCC) in Brazil is the same as in Canada. There must be a regional standard”. The SCC parameter should be decided based on different farming methods, confined and free-range, because SCC increases when the animal covers greater distances during the day. According to the respondent, the standard does not differentiate the ecological milk produced in native pastures from, which is a particular characteristic of the region.

The main change noted by the interviewees in the regulations was the parameters related to the quality of milk produced on rural farms. The new parameters are more stringent than the previous standards. To meet the quality parameters for milk, the dairy sector must comply with other necessary measures and rules, such as regarding the qualifications of the milk producers and the equipment and facilities that they must use. These compliances require investment by both the establishments that collect milk and the milk producers and have an impact on production costs in general. These requirements are especially difficult to meet for producers who lack capital and qualifications, who earlier sold milk in jugs directly to consumers. Thus, such producers need to evolve from delivering milk in carts to collecting milk in refrigerated tanks and from hand milking to automatic milking. To do so, it is necessary to support these institutions in the implementation of rules so that everyone can obtain the professional qualifications to remain in milk production. Hoang et al. [

15] present an example of this support with a public policy to promote institutions that qualify milk producers through training, information, communication, and consulting in Vietnam.

The other rules laid down in Normative Instruction No. 77 that affect milk producers are that the temperature at the point of collection on the farm should be below 4 °C; the time elapsed between milk collection and its reception at the cooling station or processing plant should not exceed 48 h; and the temperature at the time of reception at the cooling station should be below 7 °C [

14].

In their self-report, PS41 said that the roads in the region are difficult, and the long time spent transporting milk affects the quality of milk. In the same vein, PS23 reported that collection sometimes occurs every four days, which may cause the loss of the milk stored at the farm. According to PS41, the regions have varied infrastructures and climatic conditions. The milk producers who had no infrastructure and access to resources abandoned milk production. Thus, standardization may compel the less privileged milk producers on remote farms connected by substandard roads with the headquarters and located in areas with unreliable power grids to opt out of the supply chain. Therefore, the peculiarities of such regions of Brazil should be taken into consideration while deciding the quality standards.

On the other hand, according to other interviewees, these changes have benefited milk production because the product delivered to the industry now is of better quality. The dairy may even reward the producer who delivers milk that exceeds the minimum standards. However, this bonus payment is not a part of the rules. In spontaneous statements, many producers admitted that though the rules set the quality standards, the producers are rewarded only for quantity. Earlier, a bonus was paid for quality.

PS42 said, “Earlier, we used to lose a lot of milk, but now we do not because we have to follow the standards”. PS3 argued that the standards are essential and provided a specific example saying that some producers used to add water to milk to increase the quantity. This stopped when the quality standards were imposed. Now the milk is of better quality and safe for use since the entire production process is controlled. Now, acceptance by dairies is ensured, which may help in accessing other markets. This means, for the producer, the possibility of selling the product improves, which is important while the competition among dairies for supplying a product of superior quality to other regions is intensifying. The possibility of selling the product develops the sustainability of the milk supply chain and guarantees the sale of milk at a suitable price. This, in turn, enables the milk producers to invest in new technologies and stay in business.

When questioned about the milk producers feeling pressurized by the imposition of standards, most interviewees agreed that the milk producers felt pressurized. They added that especially the smaller milk producers who do not have technicians working for them or the necessary resources to invest in technology to comply with the standards or are not qualified enough to understand the rules felt pressurized. Small producers, despite playing a fundamental role in food delivery, are the weakest link in the production chains [

16]. The pressure is felt especially by the milk producers who cannot meet the established standards and may suffer the penalty of suspension of the collection of their product.

The interviewees said that the rules initially discouraged and rendered some milk producers unviable. According to ES4, because the price of milk paid to the producer does not justify the stringency of the rules and the introduction of soybean cultivation in the municipality, many milk producers preferred to lease their land for soybean cultivation over milk production. For ES5, seasonal producers who stop delivering milk for a few months are more affected by the rules “because they are not focused on milk production. Therefore, they have infrastructure that is inadequate to meet the rules”. On the other hand, the interviewee believed that the traditional milk producers who have been in this business for years are less affected.

From the perspective of ES1, the way the rules were initially introduced caused apprehension among producers. Later, however, they realized that it was possible to adapt to the rules when they began to implement the necessary procedures.

The dairy regions rely on several institutions that have been organized to engage in activities that support the dairy sector. According to the interviewees, through the “Mais Leite Alegrete” (More Milk Alegrete) program run by the municipal governments of the Alegrete region, synergy is created among four institutions that work to develop the local milk production, namely, Emater, the Secretariat of Agriculture, the Association of Dairy Farmers and Producers (ACRIPLEITE), and the Maronna Foundation. This group of institutions organizes actions to support producers and establishes ties with other institutions, such as the National Service for Rural Training (SENAR), the Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service (SEBRAE), the universities, and Embrapa.

The institutions also organize Embrapa’s Balde Cheio (Full Bucket) project, under which some milk producers are continuously monitored by an accredited professional. According to EA3, the project directly serves the producer and also trains and qualifies technicians through partner entities.

When Embrapa implements a project directly for a milk producer, it results in the translation, implementation, and monitoring of the achievement of standards. According to ES5, milk quality is monitored at the observation units. PA62 reported that the “Balde Cheio” program improved the quality of the milk produced on the farm by 100%”.

In EA3′s view, the regulations introduce the producers to some concepts that are not a part of the producer’s daily life but are now applied to the whole of Brazil. However, some concepts applicable to specific regions are not understood, and the milk producers need the support of the institutions to understand them. Ahikiriza et al. [

17] show that this fact also occurs in Uganda, where dairy farms have different knowledge availabilities, most of them being subsistence, extensive, and low productivity, that need agricultural extension advice specific to the local context. Therefore, the meso-institutions adapt and translate the rules at the regional level for producers.

Interviewees from Sant’Ana do Livramento identified six institutions that are active in milk quality operations in the region. Among them, local production arrangement (LPA) in Sant’Ana do Livramento is noteworthy. It develops mutual actions to maximize harmony with the environment while preserving the man in the field [

18]. LPA aims to develop the activity in the region through support in social activities, training, and technological innovation.

As in Alegrete, Emater is another active institution in Sant’Ana do Livramento. In its work, dairy activity is a major focus of action, and it aims to prevent the decline in the number of milk producers [

19]. The entity supports producers in improving the quality of milk. Since one of its aims is to develop milk producers’ expertise in their business, Emater is a meso-institution that translates the standards of milk quality for the milk producers.

Thus, Emater, the cooperative of producers (Cooperforte), the Secretariat of Agriculture, Embrapa, and the universities conduct activities aimed at promoting milk production in the region. According to ES1, before MAPA’s IN 76 and IN 77 came into effect, Emater, along with local institutions, held meetings for translating the old standards. ES4 noted that groups of milk producers organized technical lectures in collaboration with the local cooperatives and the LPA to spread information about the standards. That knowledge has been useful for understanding the new regulations.

As for the implementation of the standards, in addition to the “Balde Cheio” project in Alegrete, there are observation units and assisted farms, which EA3 considered necessary for imparting to milk producers a better understanding of the standards. The interviewees attributed this inability of the meso-institutions to extend these services to more milk producers to the lack of staff and budgetary constraints.

The final question that the interviewees answered was whether the producer would be able to implement the rules without support from these institutions. In Alegrete, the general opinion was that the standards of milk quality could hardly be achieved without the support of the institutions for implementing the standards because several technical terms needed to be explained to the milk producers.

In Sant’Ana do Livramento, the interviewees thought that they, especially small producers, would not be able to implement the rules without the help from meso-institutions. Many had given up dairy farming because they could not comply with the new rules. This makes the need for meso-institutions quite evident in a region dominated by small producers, many of them on small farms, who cannot afford to hire private assistance.

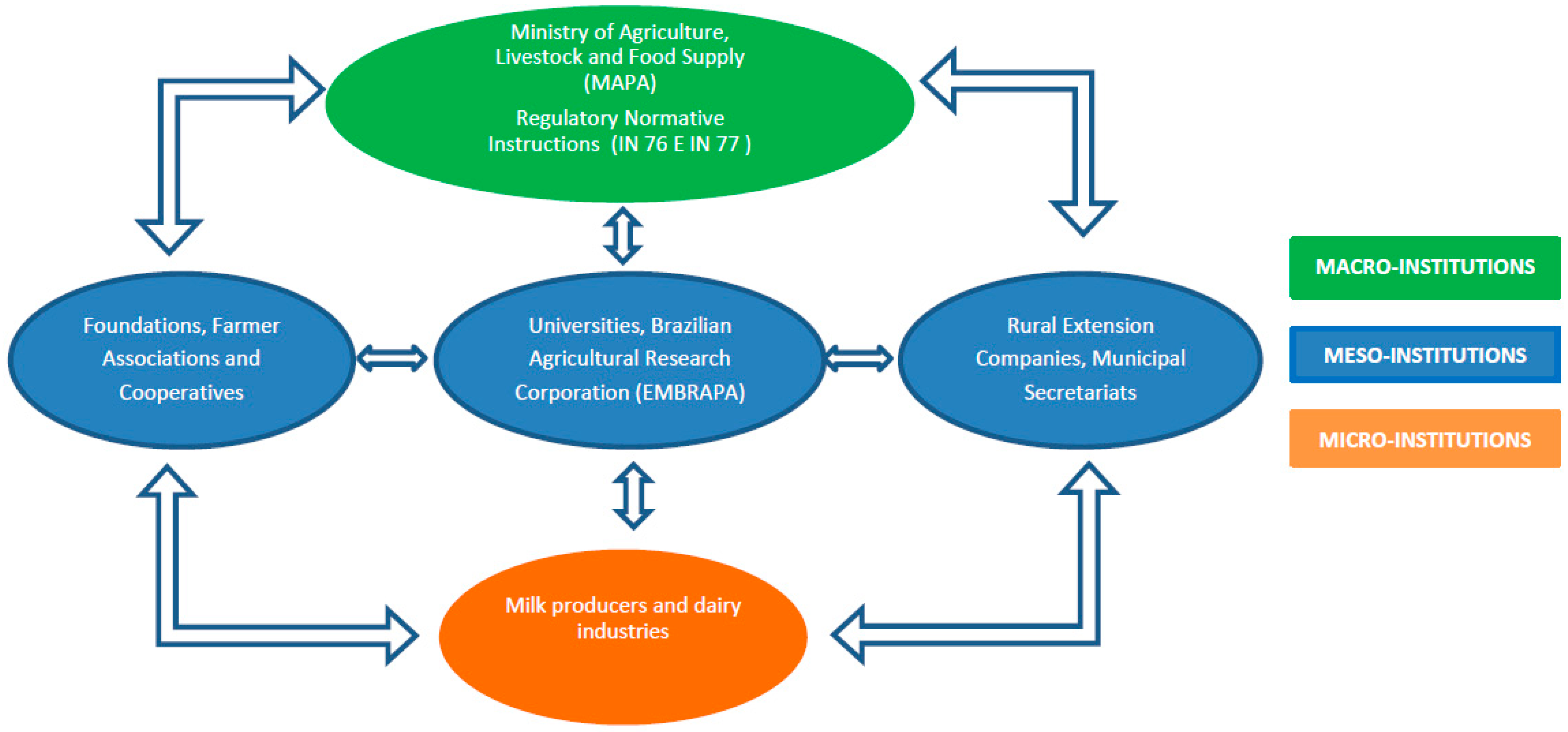

In summary,

Figure 2 illustrates the interaction between the institutions in the milk supply chain, demonstrating the meso-institutions as buffering between the micro and macro levels.

3.2. Comparing the Degree of Translation, Implementation, and Monitoring of the Rules by Meso-Institutions and Perceived Performance in the Two Regions of Brazil

The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare the degree of translation, implementation, and monitoring performed by the meso-institutions in the two regions.

Table 2 presents the results with the mean and standard deviation values for the variables, as well as the

p-values of the test.

Table 2 shows, based on the

p-value that the rejected variables in the null hypothesis are translation and implementation. Therefore, the differences in the degrees of translation and implementation by the meso-institutions between the regions are at a significance level of 1%. It is observed that the degree of translation and implementation of the standards by the meso-institutions in Alegrete is higher than in Sant’Ana do Livramento. On the other hand, the null hypotheses have been accepted for the monitoring variable. Thus, there is no difference in the degree of monitoring of the regions by the meso-institutions.

The initial analysis of Q2 and Q3 on translation with the Mann–Whitney U test shows that the activity of the meso-institutions is significantly higher in Alegrete at significance levels of less than 1%, respectively, for the two questions. This result corroborates the findings from the interviews and reports that highlight the number of courses given on milk quality in Alegrete. As PA95 stated in the self-report, “If I were to write down all the courses given on milk quality, nowhere else in RS would the number be as high as in Alegrete”.

As for Q4 on implementation, the null hypothesis is rejected (p < 0.01). Therefore, the degree of implementation of Normative Instructions No. 76 and 77 is statistically different in the two regions. The greater activity in Alegrete is reflected in the interviewees’ responses. The interviewees consider collaboration between institutions for implementing the standards of quality of milk to be essential. The implementation occurs through the activities organized at assisted farms, demonstration units, and the farms participating in the Balde Cheio program.

In Sant’Ana do Livramento, the interviewees observed that the institutions’ efforts to implement the standards did not reach most of the producers to the same extent as the translation process reached. Therefore, not all milk producers could benefit equally from technical assistance, visits, and training. The interviewees attributed this discrepancy to the shortage of staff and budgetary constraints.

As for monitoring, Q6 shows a significant difference between the studied regions (p < 0.01). Thus, the assistance provided by meso-institutions in monitoring the implementation of regulations is significantly lower in Sant’Ana do Livramento. This corroborates the results of the qualitative approach that monitoring is performed by dairies and in isolation, and that too only for members of the cooperative. According to EA6, on the other hand, in Alegrete, quality control is exercised at the assisted farms through the monthly analysis provided by the industry.

According to Ménard [

5], monitoring aims at verifying whether the product meets the standard of quality established by the rules. Thus, meso-institution monitors the adherence to the standards of milk production, i.e., checks the quality of milk to see that it falls within the parameters of the standard. This activity is of paramount importance among the activities of a meso-institution.

On the other hand, the responses to Q7 did not reveal any differences in the roles of the meso-institutions as intermediaries for conveying the demands of the milk producers in the two regions to the macro-institution (p > 0.05).

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the self-perceptions of performance of the milk producers in the two regions.

Table 3 shows the mean and standard deviation values for the variables and the

p-values of the test.

Based on the

p-value in

Table 3, there is a difference in the self-perception of performance of the milk producers in the two regions. Hence, the null hypothesis is rejected with a 1% level of significance. The perception of performance was higher among milk producers in Alegrete for variables in all the questions, except D3 (

p > 0.05). The analysis of the responses to the questions about production and profitability reveals a difference in the degree of the respondents’ perception (

p < 0.01). Thus, among Alegrete’s producers, there was a more positive perception of the increase in milk production and profit in recent years. This result aligns with the response of EA2 that the growth of Alegrete’s dairy industry is attributable to the prior collective efforts made by the entities to translate the legislation. When the standards came into effect, the milk producers followed the same routine, and this is a unique aspect of the municipality’s production. Supporting this view, EA6 expressed the belief that the synergy between the institutions has favored the increase in production in the region.

There was a significant difference between the perceptions of increased herd productivity in recent years in the two regions (p < 0.01). Again, the result for Alegrete reflected a more positive perception. This indicates a stronger role played by the institutions in the effort to improve the production performance of dairy farming. The interviewees and milk producers reported the constant presence of institutions to support the activity on the dairy farms. EA3 stated that production in Alegrete has been increasing since 2012 as a result of the institutions’ efforts. “The milk producers who did their homework increased the daily milk production from 100–200 L to almost 2000 L per day”. The strong role played by meso-institutions in Alegrete resulted in the producers’ more positive perception of the effects of full compliance with the legal requirements on milk production (p < 0.05). Meso-institutions’ effective role is evidenced in the qualitative data provided by EA3, who reported that the issue of milk quality is discussed in schools in Alegrete’s countryside. For the interviewee, it is an effort to raise the students’ awareness about the importance of complying with the standards. When a meso-institution takes the issue of milk standards to schools, it is an early interpretation of rules for the future participants and will influence the future results of the supply chain.

3.3. Effect of Meso-Institutions on Performance in Milk Production in the Western Border Region of RS—Brazil

A multiple linear regression model was used to evaluate the effect of meso-institutions on the perception of production performance in the studied regions. The dependent variable is the dairy farm’s performance, and the independent variables are, respectively, translation, implementation, and monitoring, which are the meso-institutions’ areas of action as proposed by Ménard [

4,

5]. The results of the multiple regression analysis are presented in

Table 4.

The results of the F-test in

Table 4 show that the null hypothesis is rejected with a significance level of 1%. Therefore, the validity of the model can be determined; that is, at least one independent variable influences the milk producer’s perception of performance. According to the result for the coefficient of determination (R

2), the meso-institutions’ role explains 30.3% of the variation in the perceived performance of the dairy organizations in the municipalities on the western border of RS. The economics of the dairy sector is influenced by many factors, such as the currency exchange rate, the produced volume, import of milk, weather conditions, household consumption, input prices, etc. Thus, because the sector is affected by complex variables, the model’s R

2 is relevant.

Upon analyzing the individual coefficients, only the monitoring variable seems to significantly influence the dairy organization’s performance (p < 0.01), while the other factors remain constant. Therefore, effective monitoring by the meso-institutions positively influences the milk producers’ and the milk supply chain’s performance.

On the other hand, the translation and implementation variables do not present a significant linear relationship with performance (p > 0.05). This does not mean that the role of meso-institutions in translation and implementation is not important. On the contrary, there may be a horizontal flow, from left to right, of stages that must be overcome to achieve performance. Initially, the rules are translated for the milk producers during events, such as training courses and seminars. Next, the institutions implement the mechanisms necessary to ensure that the product meets the quality standards directly on the assisted farms. Finally, monitoring is performed through milk quality analyses performed upon collection of milk on the farm, upon reception at the dairy, and in analyses in accredited laboratories.

The meso-institutions act as a buffer and translate the technical terms for the micro level to impart the necessary knowledge to the producer. This makes effective monitoring a special attribute for raising the performance of the dairy region’s production to its maximum potential. Therefore, the performance of the farms is affected when monitoring is consolidated in the dairy region, which means that translation and implementation had been previously carried out by the meso-institutions.

Oliveira, Saes, and Martino [

9] identified Conseleite as a translator of milk production standards. Schnaider et al. [

10] identified a broad network of meso-institutions with supplementary functions in the dairy sector and recognized the importance of their role at the monitoring stage in implementing the quality standards. Therefore, the promotion of the monitoring function of the meso-institutions at the micro level should be prioritized equally in all regions. This will enable the meso-institutions to monitor the implementation of the standards effectively to improve the milk supply chain’s performance.

As current food production follows a global production model, the local evidence from this study can be extended to milk supply chains in other parts of the world. Thus, the results indicate that meso-institutions are a link between norms and producers, either individually or collectively, and reduce the obstacles for milk farmers in implementing rules. Therefore, they are fundamental for the full development of milk supply chains in different regions of the world. More active meso-institutions that take into account local peculiarities may result in an expansion of milk production in different regions of the world.

It is worth mentioning that meso-institutions are also a communication channel between farmers and the macro-institutional level in order to present the need for changing the “rules of the game”. For, as Weerabahu et al. [

20], there must be an interconnection between the actors involved in the public policy-making of food security for the effective development of supply chains. In this way, this function can influence the development of new regulations and, consequently, an institutional change in the global milk supply chains.