Cotton GinTrash Feeding Amid Feed Scarcity in Sheep and Factors Driving Inclusion in the Yarn Spinning Industrial Cluster of Tamil Nadu, India

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

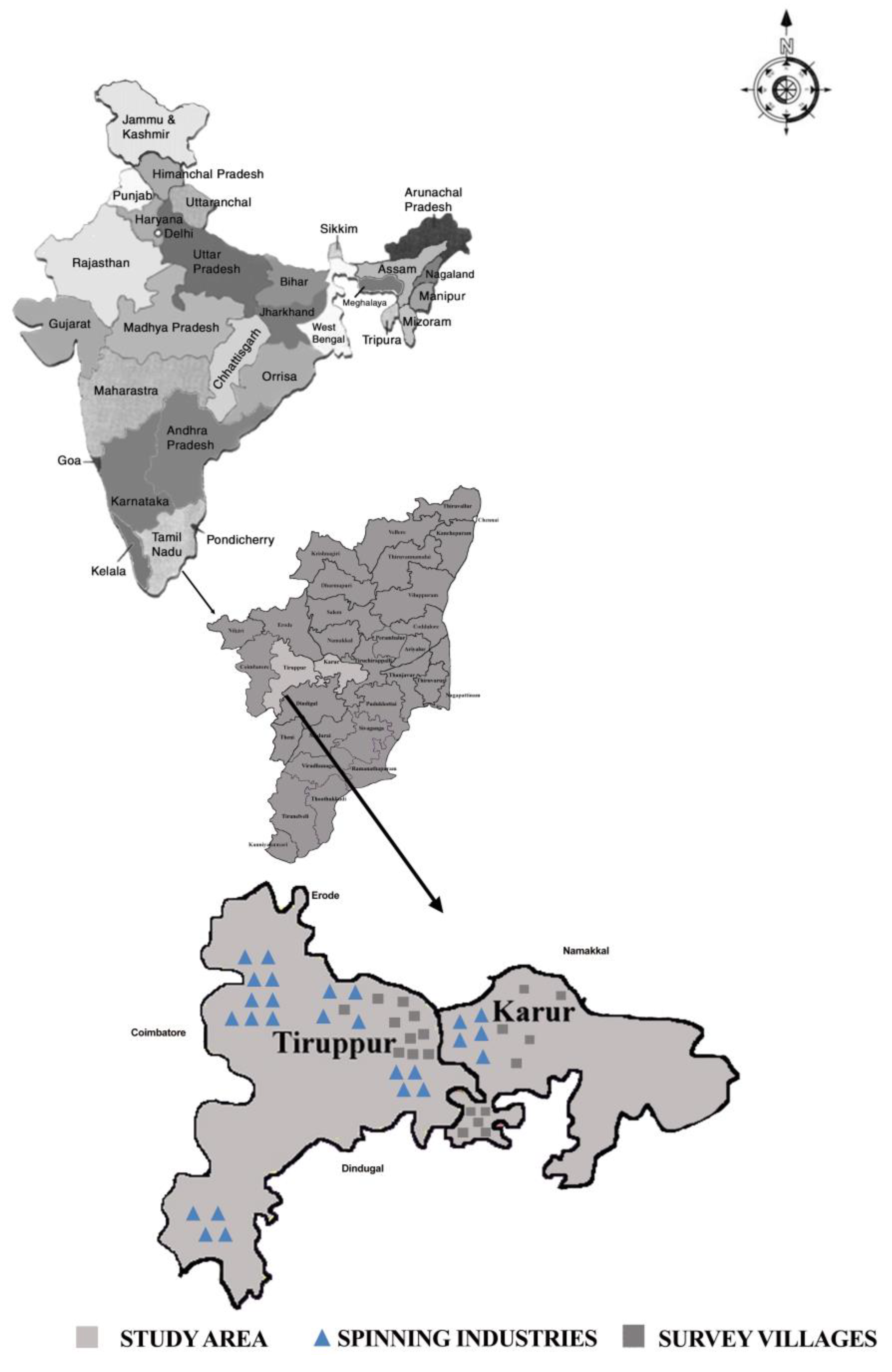

2.1. Description of Study Area

2.2. Selection of Farmers for Survey

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Determination of Nutritive Value of Cotton Gin Trash

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Socio-Economic Status of the Sheep Farmers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Porwal, K.; Karim, S.A.; Sisodia; Singh, V.K. Socio-Economic Survey of Sheep Farmers in Western Rajasthan. Indian J. Small Rumin. 2006, 14, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaravelu, N. Analysis of Sheep Production System in Southern and Northern Zones of Tamilnadu; Lambert: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh, A.; Gupta, D.C.; Mann, J.C. Constraints in Adoption of Improved Management Practices of Sheep Farming in Semi-Arid Region of Rajasthan. Indian J. Small Rumin. 2008, 14, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K. Non-Conventional Feed Resources for Small Ruminants. J. Anim. Health Behav. Sci. 2018, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Meglas, M.D.; Martinez, T.A.; Gailego, J.A.; Sanchez, M. Silage of Byproducts of Artichoke. Evaluation and Modification of the Quality of Fermentation. Options Mediterr. Ser A 1991, 16, 141–143. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari, M.H.; Tahmasbi, A.M.; Khorvash, M.; Naserian, A.A.; Vakili, A.R. Effects of Pistachio By-Products in Replacement of Alfalfa Hay on Ruminal Fermentation, Blood Metabolites, and Milk Fatty Acid Composition in Saanen Dairy Goats Fed a Diet Containing Fish Oil. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2014, 42, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnklong, C.; Cone, J.W.; Pellikaan, W.; Hendriks, W.H. Utilization of Rice Straw and Different Treatments to Improve Its Feed Value for Ruminants: A Review. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 23, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, G.; Ganai, A.; Sheikh, F.; Bhat, S.A.; Masood, D.; Mir, S.; Ahmad, I.; Bhat, M.A. Effect of Feeding Urea Molasses Treated Rice Straw along with Fibrolytic Enzymes on the Performance of Corriedale Sheep. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2017, 5, 2626–2630. [Google Scholar]

- ANGRAU. ANGRAU Crop Outlook Reports of Andhra Pradesh COTTON–January to December 2021. 2022. Available online: https://angrau.ac.in/downloads/AMIC/OutlookReports/2021/4-COTTON_January%20to%20December,%202021.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- GoI, Ministry of Textiles. Cotton Sector. Annexure VII (361555/2022/Cotton). 2022. Available online: https://texmin.nic.in/sites/default/files/Cotton%20Sector.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Lakwete, A. Inventing the Cotton Gin-Machine and Myth in Antebellum America; JHU Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, T.M.; Lansford, R.R. Technical Report on Survey of Cotton Gin and Oil Seed Trash Disposal Practices and Preferences in the Western U.S.; New Mexico State University: Las Cruces, NM, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, G.M.; Poore, M.H.; Paschal, J.C. Feeding Cotton Products to Cattle. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2002, 18, 267–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.B.; Rankins, D.L. Comparison of Cotton Gin Trash and Peanut Hulls as Low-Cost Roughage Sources for Growing Beef Cattle. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2008, 24, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, A.N.; Kennedy, I.R. Calculation of Pesticide Degradation in Decaying Cotton Gin Trash. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2008, 81, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, A.L.; Beck, P.A.; Foote, A.P.; Pierce, K.N.; Robison, C.A.; Hubbell, D.S.; Wilson, B.K. Effects of Utilizing Cotton Byproducts in a Finishing Diet on Beef Cattle Performance, Carcass Traits, Fecal Characteristics, and Plasma Metabolites. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, skaa038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myer, R.O. Cotton Gin Trash: Alternative Roughage Feed for Beef Cattle; University of Florida IFAS: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The Cotton Corporation of India Ltd., India, 2011. Annual Report. 2011. Available online: https://www.cotcorp.org.in/Writereaddata/Downloads/Annual_Rep1011.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Fairlabor. Understanding the Characteristics of the Sumangali Scheme in Tamil Nadu Textile & Garment Industry and Supply Chain Linkages. 2012. Available online: https://www.solidaridadnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/migrated-files/publications/Understanding_Sumangali_Scheme_in_Tamil_Nadu.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Agblevor, F.A.; Cundiff, J.S.; Mingle, C.; Li, W. Storage and characterization of cotton gin waste for ethanol production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2006, 16, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasson, J.A. A review of cotton gin trash disposal and utilization. In Beltwide Cotton Production Research Proceedings; National Cotton Council: Memphis, TN, USA; Las Vegas, NV, USA, 1990; pp. 689–705. [Google Scholar]

- Thirunavukkarasu, D.; Narmatha, N. Lab to land–factors driving adoption of dairy farming innovations among Indian farmers. Curr. Sci. 2016, 111, 1231–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukkarasu, D.; Jothilakshmi, M.; Silpa, M.V.; Sejian, V. Factors driving adoption of climatic risk mitigating technologies with special reference to goat farming in India: Evidence from meta-analysis. Small Rumin. Res. 2022, 216, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, Association of Official Analytical Chemists 19th Edition; AOAC: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- IS 14827; Animal Feeding Stuff—Determination of of Crude Ash by Bureau of Indian Standards. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 2000.

- IS 14826; Animal Feeding Stuff—Determination of Ash insoluble in Hydrochloric acid by Bureau of Indian Standards. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 2000.

- Tilley, J.M.A.; Terry, R.A. A two-stage technique for the in vitro digestion of forage crops. J. Br. Grassland Sco. 1963, 18, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.T.V.; Thammi Raju, D.; Ravindra Reddy, Y. Adoption of Sheep Husbandry Practices in Andhra Pradesh, India. Livest. Res. Rural. Dev. 2008, 20, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Thilakar, P.; Krishnaraj, R. Profile Characteristics of Sheep Farmers: A Survey in Kancheepuram District of Tamil Nadu. Indian J. Field Vet. 2014, 5, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jothilakshmi, M.; Thirunavukkarasu, D.; Sudeepkumar, N.K. Exit of Youths and Feminization of Smallholder Livestock Production–a Field Study in India. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2014, 29, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukkarasu, D.; Narmatha, N.; Alagudurai, S. What Drives the Adoption of Fodder Innovation(s) in a Smallholder Dairy Production System? Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study of Dairy Farmers in India. Trop. Grassl. Forrajes Trop. 2021, 9, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengateswari, M.; Geethalakshmi, V.; Bhuvaneswari, K.; Jagannathan, R.; Panneerselvam, S. District Level Drought Assessment over Tamil Nadu. Madras Agric. J. 2019, 106, 225–227. [Google Scholar]

- NABARD. Accelerating the Pace of Capital Formation in Agriculture and Allied Sector” Is the Main Theme of This Potential Linked Credit Plan for 2016-17.PLP 2016-17. 2016. Available online: https://www.nabard.org/demo/auth/writereaddata/tender/2410162220TN_Tiruppur.split-and-merged.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Shivakumara, C.; Reddy, B.S.; Patil, S.S. Socio-Economic Characteristics and Composition of Sheep and Goat Farming under Extensive System of Rearing. Agric. Sci. Dig. A Res. J. 2020, 40, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akila, N. Management and Marketing Pattern of Mecheri Sheep in Tamil Nadu; An Exploratory Analysis of Karur District. Indian J. Small Rum. 2014, 20, 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Senthilmuthukumaran, S. Impact of Mega Sheep Seed Project on Mecheri Sheep Performance and Farmers Livelihood. Master’s Thesis, Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chennai, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Meena, K.C.; Indoria, D.; Meena, G.S. Adoption of Improved Sheep Rearing Practices in the Eastern Part of Rajasthan, India. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2020, 9, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalor, W.F.; Jones, J.K.; Slater, G.A. Cotton Gin Trash as a Ruminant Feed; In Cotton Gin and Oil Mill Press; Haughton Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1975; pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, C.O.; Boga, M.; Atalay, A.I.; Guven, I.; Kaya, E. Determination of potential nutritive value of cotton gin trash produced from different feed companies. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2005, 43, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, B.; Meena, G.S.; Meena, K.C.; Singh, N. Feeding and Healthcare Management Practices Adopted by Sheep Farmers in Karauli District of Eastern Rajasthan, India. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2018, 7, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothilkashmi, M.; Akila, N. Experiences in Promoting Ensiling of Onion Crop Residue among Smallholder Dairy Farmers in Namakkal District of Tamil Nadu. Irjee 2022, 22, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moanarol; Ngullie, E.; Walling, I.; Krose, M.; Bhate, B.P. Traditional Animal Husbandry Practices in Tribal States of Eastern Himalaya, India: A Case Study. Indian J. Anim. Nutr. 2011, 28, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Balaji, N.S.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Muralidharan, J.; Thiruvenkadan, A.K.; Vasan, P.; Sivakumar, K. Effect of Feeding Cotton Gin Trash on Haematological and Serum Biochemical Values in Mecheri Lambs. Biol. Forum Int. J. 2021, 13, 228–231. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan, S.B.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Muralidharan, J.; Vasan, P.; Sivakumar, K.; Thiruvenkadan, A.K. Effect of Cotton Gin Trash Supplementation as Unconventional Feedstuff on Feed Intake and Production Characteristics of Mecheri Sheep of India. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.M.; Rivera, J.D.; Franklin, A.N.; Stone, G.W.; Tillman, D.R.; Mullinix, B.G. Evaluation of Cotton-Gin Trash Blocks Fed to Beef Cattle11Manuscript No. 12206, Approved by the Mississippi Agriculture and Forestry Experiment Station, Starkville. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2013, 29, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathini, H.; Valli, C.; Balakrishnan, V. Supplemental Strategy to Improve Nutritive Value of Cotton Gin Waste—A Potential Cattle Feed. Indian Vet. J. 2019, 96, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.R. Creating a System for Meeting the Fiber Requirements of Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1997, 80, 1463–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalafalla, M. Effect of Dietary Level of Cotton Gin Trash on Nutrients Utilization and Performance of Sudan Desert Lambs. Master’s Thesis, University of Khartoum, Khartoum North, Sudan, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Parish, J.A. Fiber in Beef Cattle Diets, Mississippi State University Extension: Starkville, MS, USA; North Mississippi Research and Extension Center: Verona, MS, USA, 2008; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Galyean, M.L.; Hubbert, M.E. Review: Traditional and Alternative Sources of Fiber—Roughage Values, Effectiveness, and Levels in Starting and Finishing Diets11Substantial Portions of This Paper Were Presented at the 2012 Plains Nutrition Council Spring Conference and Published in the Conference Proceedings (AREC 2012-26, Texas AgriLife Research and Extension Center, Amarillo). Prof. Anim. Sci. 2014, 30, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.P.; De Figueiredo, M.P.; De Quadros, D.G.; Ferreira, J.Q.; Whitney, T.R.; Luz, Y.S.; Santos, H.R.O.; Souza, M.N.S. Chemical and Biological Treatment of Cotton Gin Trash for Fattening Santa Ines Lambs. Livest. Sci. 2020, 240, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankins, D.L. The Importance of By-Products to the US Beef Industry. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2002, 18, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkle, W.; Stewart, R.; Brown, W. Using Byproduct Feeds in Supplementation Programs. Available online: https://animal.ifas.ufl.edu/beef_extension/bcsc/1995/docs/kunkle.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño, R.; Sujan, M.; Kacker, M.; Sujan, H. Managing Consumer Uncertainty in the Adoption of New Products: Temporal Distance and Mental Simulation. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, J.W.C.; Frambach, R.T.; Bijmolt, T.H.A. Generalizations on Consumer Innovation Adoption: A Meta-Analysis on Drivers of Intention and Behavior. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2011, 28, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, F.J.; Barreiro-Hurlé, J.; Van Bavel, R. Behavioural Factors Affecting the Adoption of Sustainable Farming Practices: A Policy-Oriented Review. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2019, 46, 417–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variables | Definition | Mean ± Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Chronological age of farmers in years | 50.33 ± 9.38 |

| Education | Number of years of formal education | 9.60 ± 3.76 |

| Gender | Women managed farms coded as 1; otherwise as 0 | 0.04 ± 0.19 |

| Experience | Number of years of experience in sheep farming | 24.25 ± 10.42 |

| Landholding | Land owned by sheep farmers (in acres) | 16.04 ± 6.38 |

| Occupation | Sheep farming as primary occupation coded as -2; sheep farming withagriculture—1 and sheep farming with non-farm sector as 0 | 0.96 ± 0.40 |

| Income from sheep | Refers to annual net income from sheep farming (in USD) | 1871.95 ± 548.78 |

| Flock size | Total number of sheep in the household | 65.85 ± 22.95 |

| Grazing duration | Number of hours of sheep grazed in a day | 9.17 ± 1.05 |

| Access to labour | No challenges in accessing labour force for farming activities—0; otherwise, as 1 | 0.18 ± 0.38 |

| Years of feeding | Number of years of feeding cotton gin for sheep | 2.48 ± 1.51 |

| Feeding method | Soaking in water and feeding coded as 1; otherwise as 0 | 0.79 ± 0.41 |

| Type of gin | Coarse CGT coded as 1; fine type as 0 | 0.64 ± 0.48 |

| Challenge in gin feeding | Farmers reporting foreign particles and dust in CGT as 1; otherwise as 0 | 0.59 ± 0.50 |

| Price | Price per kilogram of cotton gin trash (in USD) | 0.17 ± 0.05 |

| Feeding to cow | Feeding CGT to cow as 1; otherwise as 0 | 0.64 ± 0.48 |

| Level of replacement | Level of replacement refers to inclusion of CGT in percentages as an alternative to conventional roughages on dry matter basis | 50.67 ± 8.76 |

| Particulars | Mean± SE | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse Type Cotton Gin Trash (Kotta Panju) | Fine Type Cotton Gin Trash (Micro Waste Panju) | ||

| Proximate composition | |||

| Moisture | 10.13 ± 0.57 | 7.87 ± 0.25 | 0.030 |

| Crude protein | 14.15 ± 0.62 | 13.64 ± 0.30 | 0.444 |

| Crude fibre | 38.02 ± 1.66 | 40.28 ± 1.78 | 0.408 |

| Ether extract | 4.06 ± 0.77 | 3.96 ± 0.33 | 0.763 |

| Total ash | 7.01 ± 0.45 | 8.03 ± 0.65 | 0.209 |

| Gross energy (kcal/Kg) | 3787 ± 25.31 | 3765 ± 66.29 | 0.766 |

| Acid insoluble ash | 1.36 ± 0.26 | 0.73 ± 0.15 | 0.093 |

| Mineral profile | |||

| Calcium | 1.23 ± 0.15 | 1.24 ± 0.09 | 0.970 |

| Phosphorous | 0.38 ± 0.08 | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 0.012 |

| Iron | 0.23 ± 0.11 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.618 |

| Manganese (ppm) | 148.26 ± 4 1.58 | 390.00 ± 77.01 | 0.012 |

| Copper (ppm) | 21.19 ± 3.69 | 27.21 ± 1.95 | 0.124 |

| Fibre fractions | |||

| NDF | 65.52 ± 2.31 | 64.18 ± 2.36 | 0.017 |

| ADF | 50.14 ± 2.09 | 48.98 ± 1.63 | 0.001 |

| Cellulose | 23.64 ± 0.54 | 24.51 ± 0.99 | 0.788 |

| Hemicellulose | 15.20 ± 0.76 | 15.38 ± 0.49 | 0.652 |

| Lignin | 15.67 ± 0.76 | 18.00 ± 0.25 | 0.032 |

| In vitro apparent dry matter digestibility (IVADMD) | |||

| At 12 h incubation time | 30.80 ± 0.29 | 27.55 ± 0.30 | 0.001 |

| At 24 h incubation time | 39.11 ± 0.92 | 32.58 ± 0.61 | 0.001 |

| Gossypol (ppm) | |||

| Gossypol level | 1.970 ± 1.17 | 0.658 ± 0.22 | 0.299 |

| Predictor Variables | Estimated Coefficient | Standard Error | Odds Ratio # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.937 | 1.475 | 2.551 |

| Education | −0.12 | 0.103 | 0.887 |

| Landholding | 0.21 | 0.08 | 1.234 ** |

| Flock size | −0.074 | 0.025 | 0.929 ** |

| Grazing duration | 0.491 | 0.415 | 1.633 |

| Feeding of cotton gin to cattle | −1.588 | 0.783 | 0.204 * |

| Access to labour | 2.243 | 0.88 | 9.421 * |

| Feeding method | 1.343 | 1.04 | 3.83 |

| Constant | −4.519 | 4.457 | 0.011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sri Balaji, N.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Muralidharan, J.; Vasan, P.; Thiruvenkadan, A.K.; Sivakumar, K.; Sankar, V.; Kumaravel, V.; Thirunavukkarasu, D. Cotton GinTrash Feeding Amid Feed Scarcity in Sheep and Factors Driving Inclusion in the Yarn Spinning Industrial Cluster of Tamil Nadu, India. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1552. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13081552

Sri Balaji N, Ramakrishnan S, Muralidharan J, Vasan P, Thiruvenkadan AK, Sivakumar K, Sankar V, Kumaravel V, Thirunavukkarasu D. Cotton GinTrash Feeding Amid Feed Scarcity in Sheep and Factors Driving Inclusion in the Yarn Spinning Industrial Cluster of Tamil Nadu, India. Agriculture. 2023; 13(8):1552. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13081552

Chicago/Turabian StyleSri Balaji, Nagarajan, Subramaniam Ramakrishnan, Jaganadhan Muralidharan, Palanisamy Vasan, Aranganoor Kannan Thiruvenkadan, Karuppusamy Sivakumar, Venkatachalam Sankar, Varadharajan Kumaravel, and Duraisamy Thirunavukkarasu. 2023. "Cotton GinTrash Feeding Amid Feed Scarcity in Sheep and Factors Driving Inclusion in the Yarn Spinning Industrial Cluster of Tamil Nadu, India" Agriculture 13, no. 8: 1552. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13081552