Rural Depopulation in Spain: A Delphi Analysis on the Need for the Reorientation of Public Policies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Depopulation in the National Context

1.2. Theoretical Framework and Previous Research

1.3. Government Initiatives for Achieving More Cohesive Territories

2. Research Methodology

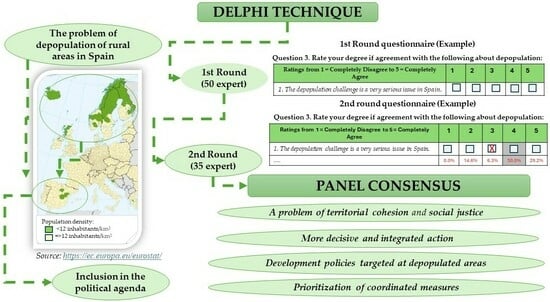

2.1. Delphi Method

2.2. Expert Panel Profile and Study Objectives

3. Results

3.1. Importance of the Depopulation Challenge in Spain

3.2. Need to Promote Development Policies Targeted at Depopulated Areas

3.3. Expectations Regarding the New CAP Post-2023

3.4. Prioritization of Coordinated Measures to Support Depopulated Rural Areas

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Michaels, G.; Rauch, F.; Redding, S. Urbanization and Structural Transformation. Q. J. Econ. 2012, 127, 535–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCDE. Cities in the world: A new perspective on urbanisations. In OCDE Urban Studies; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and Comisión Europea: Paris, France, 2020; 171p. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, E.; Moral-Benito, E.; Ramos, R. Tendencias recientes de la población en las áreas rurales y urbanas de España. In Documentos Ocasionales; Banco de España: Sevilla, Spain, 2020; Volume 2027, 42p. [Google Scholar]

- INE. Padrón Municipal de Habitantes; Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Banco de España. La Distribución Espacial de la Población en España y sus Implicaciones Económicas. 2021, pp. 271–318. Available online: https://repositorio.bde.es/handle/123456789/16628 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Gutiérrez, E.; Moral-Benito, E.; Ramos, R.; Oto-Peralías, D. The spatial distribution of population in Spain: An anomaly in european perspective. In Documentos de Trabajo; Banco de España: Sevilla, Spain, 2020; Volume 2028, 322p. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación BBVA-IVIE. Despoblación de las provincias españolas. Esenciales 2019, 37, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Molina de la Torre, I. La despoblación en España: Un análisis de la situación. Inf. Comunidades Autónomas 2018, 2018, 66–87. [Google Scholar]

- Camarero, L.; Cruz, F.; González, M.; El Pino, J.A. La población rural en España. De los desequilibrios a la sostenibilidad social. In Colección Estudios Sociales; Fundación La Caixa: Barcelona, Spain, 2009; Volume 27, 199p. [Google Scholar]

- Camarero, L. Despoblamiento, baja densidad y brecha rural: Un recorrido por una España desigual. In Panorama Social; FUNCAS: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Recaño, J. La sostenibilidad demográfica de la España vacía. Perspect. Demogràfiques 2017, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Alloza, M.; González-Díez, V.; Moral-Benito, E.; Tello-Casas, P. El acceso a servicios en la España rural. In Documentos Ocasionales; Banco de España: Sevilla, Spain, 2021; Volume 2122, 44p, Available online: https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/SES/Secciones/Publicaciones/PublicacionesSeriadas/DocumentosOcasionales/21/Fich/do2122.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Jiménez, C.; Tejero, H. Cierre de oficinas bancarias y acceso al efectivo en España. Rev. Estab. Financ. Banco España 2018, 34, 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Oliver, M. Financial exclusion and branch closures in Spain after the Great Recession. Reg. Stud. 2019, 53, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unión Europea. La respuesta de la UE al reto demográfico. In Dictamen del Comité Europeo de las Regiones; Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea DOUE: Luxembourg, 2017; Volume C 017/08, 6p. [Google Scholar]

- MPTFP. Estrategia Nacional Frente al Reto Demográfico: Directrices Generales; Ministerio de Política Territorial y Función Pública: Madrid, Spain, 2019; 17p, Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/reto-demografico/temas/directricesgeneralesenfrd_tcm30-517765.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- MITECO. Plan de Recuperación. 130 Medidas Frente al Reto Demográfico; Ministerio de Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico: Madrid, Spain, 2021; 129p, Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/reto-demografico/temas/medidas-reto-demografico.html (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- CES. El Medio Rural y Su Vertebración Social y Territorial; Informe 01, Sesión Ordinaria del Pleno de 24 de Enero; Consejo Económico y Social de España: Madrid, Spain, 2018; 172p. [Google Scholar]

- CES. Un Medio Rural Vivo y Sostenible; Informe 02, Sesión Extraordinaria del Pleno de 7 de Julio; Consejo Económico y Social de España: Madrid, Spain, 2021; 234p, Available online: https://www.ces.es/documentos (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- FEMP. Listado de Medidas Para Luchar Contra la Despoblación en España. Documento de Acción. Comisión de Despoblación; Federación Española de Municipios y Provincias: Madrid, Spain, 2017; 26p, Available online: https://www.femp.es/sites/default/files/doc_despob_definitivo_0_0.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Dalkey, N.C.; Helmer, O. An Experimental Application of Th e Delphi. Method to the Use of Experts. Manag. Sci. 1963, 9, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodyakov, D.; Grant, S.; Kroger, J.; Gadwah-Meaden, C.; Motala, A.; Larkin, J. Disciplinary trends in the use of the Delphi method: Abibliometric analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, U.G.; Clarke, R.E. Theory and applications of the Delphi technique: A bibliography (1975–1994). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1996, 53, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, E. Galicia Rural y el año 2000: Un Análisis Tipo Delphi; Comunicaciones INIA: Serie Economía y Sociología Agrarias; Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Agrarias: Madrid, Spain, 1979; Volume 6, 52p. [Google Scholar]

- Fearne, A. The CAP in 1995-A Qualitative Approach to Policy Forecasting. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 1989, 16, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Carrasco Pleite, F.; Colino Sueiras, B.; Gómez Cruz, J.A. Rural poverty and development policies in Mexico. In Estudios Sociales: Revista de Alimentación Contemporánea y Desarrollo Regional; Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, A. C. en Hermosillo: Sonora, México, 2014; Volume 22, pp. 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- Abreu, I.; Mesias, F.J. The assessment of rural development: Identification of an applicable set of indicators through a Delphi approach. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamdeta, J. Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2006, 73, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeta, J. El Método Delphi. Una Técnica de Previsión del Futuro; Ariel Social: Barcelona, Spain, 2002; 223p. [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla, V.; Sáez, L.A. La Despoblación Rural en España: Génesis de un Problema y Políticas Innovadoras; Centro de Estudios de Despoblación y Desarrollo de Áreas Rurales (CEDDAR) y red de Áreas Escasamente Pobladas del Sur de Europa (SSPA): Zaragoza, Spain, 2017; 24p. [Google Scholar]

- CIS. Barómetro de Febrero; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS): Madrid, Spain, 2019; Volume 3240, 42p.

- Bello Paredes, S.A. La despoblación en España: Balance de las políticas públicas implantadas y propuestas de future. In Revista de Estudios de la Administración Local y Autonómica; Nueva Época: Vila Seca, Spain, 2023; Volume 19, pp. 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- ENRD. Strategy for Inner Areas in Italy; Working Document; European Network for Rural Development: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2020; 4p. [Google Scholar]

- MAPA. Plan Estratégico de España Para la PAC Post 2020; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2021; 3721p. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/pac/pac-2023-2027/plan-estrategico-pac.aspx (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Unión Europea. Una Visión a Largo Plazo Para las Zonas Rurales de la UE: Hacia Unas Zonas Rurales más Fuertes, Conectadas, Resilientes y Prósperas Antes de 2040. Dictamen de la Sección de Agricultura, Desarrollo Rural y Medio Ambiente. Comunicación de la Comisión al Parlamento Europeo, al Consejo; Unión Europea: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Volume NAT/839, 12p, Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/es/newsroom/news/2021/06/30-06-2021-long-term-vision-for-rural-areas-for-stronger-connected-resilient-prosperous-eu-rural-areas (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Kompil, M.; Jacobs-Crisioni, C.; Dijkstra, L.; Lavalle, C. Mapping accessibility to generic services in Europe: A market-potential based approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerlich, F.J.; Maudos, J.; Mollá, S. Distribución de la Población y Accesibilidad a Los Servicios en España; Monografías, Fundación Ramón Areces e Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Económicas (IVIE): Madrid, Spain, 2021; 160p, Available online: https://www.ivie.es/es_ES/ptproyecto/distribucion-la-poblacion-acceso-los-servicios-publicos/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Herce, J.A.; Esteban, S.; De Frutos, P.; García, B. Una fiscalidad diferenciada para el progreso de los territorios despoblados en España. Justificación, valoración e impacto socioeconómico. In Proyecto de Cooperación Medida LEADER. Desafío SSPA 2021; Southern Sparsely Populated Areas (SSPA): Teruel, España, 2019; 69p. [Google Scholar]

- SSPA. Documento de Posición; Southern Sparsely Populated Areas (SSPA): Teruel, España, 2017; 28p. [Google Scholar]

- Latocha-Wites, A.; Kajdanek, K.; Sikorski, D.; TomczaK, P.; Szmytkie, R.; Miodonska, P. Global forces and local responses—A “hot-spots” model of rural revival in a peripheral region in the Central-Eastern European context. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 106, 103212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 34, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero, F. De la plétora demográfica al vaciamiento general: La difícil situación del campo en el interior de España. Rev. Desarro. Rural Sosten. 2017, 33, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Baylina, M.; Montserrat Villarino, M.; Garcia Ramon, M.D.; Mosteiro, M.J.; Porto, A.M.; Salamaña, I. Género e innovación en los nuevos procesos de re-ruralización en España. Finisterra 2019, 54, 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Reig, E.; Goerlich, F.J.; Catarino, I. Delimitación de Áreas Rurales y Urbanas a Nivel Local. Demografía, Coberturas del Suelo y Accesibilidad; Informe BBVA: Bilbao, Spain, 2016; Informes Economía y Sociedad; 138p, Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=910254 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Paniagua, A. La despoblación, una cuestión de Estado al margen de los cambios políticos. Diario ABC, 25 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moyano Estrada, E. Discursos, certezas y algunos mitos sobre la despoblación rural en España. Panor. Soc. 2020, 31, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Cayela, J.; Santos Álvarez, R. Territorios rurales inteligentes como modelo de desarrollo”. La España rural: Retos y oportunidades de futuro. Fundación Cajamar. Mediterráneo Económico 2022, 35, 417–439. [Google Scholar]

- Bandrés Moliné, E.; Azón Puértolas, V. La España despoblada: Tendencias recientes. Economistas 2023, 181, 266–273. [Google Scholar]

- Colino Sueiras, J.; Martínez-Carrasco Pleite, F.; Losa Carmona, A.; Martínez Paz, J.M.; Pérez Morales, A.; Albadalejo García, J.A. Las zonas rurales en la Región de Murcia. Consejo Económico y Social de la Región de Murcia (CESRM). Estudios 2022, 44, 398. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=942561 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- SSPA. Combatir Con Éxito la Despoblación Mediante un Modelo de Desarrollo Territorial. La Experiencia de Highlands and Islands Enterprise. Southern Sparsely Populated Areas (SSPA): Teruel, España, 2021; 86p. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco Caballero, F. Despoblación y nivelación financiera municipal en el marco de la Carta Europea de Autonomía Local. Rev. Estud. Adm. Local Autonómica 2022, 18, 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano Estrada, E.; Gómez Benito, C. La Estrategia Nacional Frente al Reto Demográfico. Una política de Estado para un Problema Transversal de los Territorios. Mediterráneo Económico. Fundación Cajamar. En “La España Rural: Retos y Oportunidades de Futuro”. 2022, Volume 35, pp. 443–462. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=858317 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

| Characteristics | Situation Generates | Effects That Reinforce |

|---|---|---|

| Low population density | More challenges and insufficient service provision. | The lack of inhabitants affects the provision of public and private services, as well as their economic viability. |

| Demographic aging and youth migration | Lack of youth and decline in workforce. | Issues with the sustainability of basic services and the viability of activities, leading to negative population growth. |

| Limited access to basic services | The lack of access to essential services such as education, health, and transportation, whether public or private. | Areas become less attractive for the population, especially for families and the younger population. |

| Closure of public services | The closure of schools, health centers, and other public services. | An indicator of the decline of a region and can accelerate depopulation by reducing the quality of life. |

| Limited economic diversification | Dependency on agriculture or traditional industries. | Increased vulnerability, the lack of opportunities, and difficulties in adapting to economic changes. |

| Lack of job opportunities | The absence of employment, particularly for young and women. | A key factor driving migration to urban or more prosperous areas. |

| Decline in infrastructure | The lack of investment in infrastructure such as roads, communications, and public services. | Contributes to the decline of a region, increasing the risk of depopulation, leading to territorial competitiveness and the quality of life of its citizens being relegated to a secondary status. |

| Geographical isolation of remote areas | Remote areas or those with difficult access may experience higher depopulation. | The lack of connectivity and geographical isolation hinders economic and social development. |

| Lack of attraction for new residents | The lack of capacity or public initiatives to attract new residents. | Depopulation processes persist, accelerating despite the implementation of initiatives that prove ineffective (affordable housing programs, business opportunities, childbirth support, regionalization, and decentralization of services, etc.). |

| Local Development Agents | Private Sector | AAPP | Researchers | European Union Institutions | N° | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Round | 14 | 10 | 8 | 14 | 4 | 50 |

| 2nd Round | 10 | 4 | 6 | 11 | 4 | 35 |

| Rating from 1 to 5 | Relative Frequency (%) | Me | Md | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ratings from 1 = Completely Disagree to 5 = Completely Agree) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1. The depopulation challenge is a very serious issue in Spain | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 37.1 | 62.9 | 4.6 | 5 |

| 2. Combating depopulation in rural areas should be one of the major national challenges | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.7 | 28.6 | 65.7 | 4.6 | 5 |

| 3. Depopulation in rural areas and small municipalities is a complex and challenging issue to reverse. | 0.0 | 8.6 | 5.7 | 48.6 | 37.1 | 4.1 | 4 |

| 4. Citizens are aware of the depopulation problem and its connection to the multifunctionality of rural areas. | 17.1 | 45.7 | 22.9 | 14.3 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 2 |

| Rating from 1 to 5 | Relative Frequency (%) | Me | Md | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1 = Very Low Need for Improvement and 5 = Very High Need for Improvement) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1st. Availability of job/employment/business opportunities. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.6 | 22.9 | 68.6 | 4.6 | 5 |

| 2nd. Access to healthcare or childcare for children and the elderly. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.6 | 40.0 | 51.4 | 4.4 | 5 |

| 3rd. Infrastructure and transportation connections (e.g., with urban areas and other towns). | 2.9 | 2.9 | 31.4 | 11.4 | 51.4 | 4.1 | 5 |

| 4th. Digital infrastructure (broadband and internet access). | 0.0 | 5.7 | 17.1 | 37.1 | 40.0 | 4.1 | 5 |

| 5th. Access to local services, such as shops, post offices, pharmacies, etc. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 22.9 | 42.9 | 34.3 | 4.1 | 4 |

| 6th. Access to education and training services. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 60.0 | 25.7 | 4.1 | 4 |

| 7th. Access to cultural and recreational activities. | 0.0 | 5.7 | 37.1 | 31.4 | 25.7 | 3.8 | 4 |

| 8th. Threats to the natural environment and its protection. | 2.9 | 11.4 | 34.3 | 28.6 | 22.9 | 3.6 | 4 |

| 9th. Availability of housing. | 0.0 | 25.7 | 37.1 | 14.3 | 22.9 | 3.3 | 3 |

| 10th. Access and affordability of various energy options (gas, electricity, etc.). | 2.9 | 14.3 | 37.1 | 37.1 | 8.6 | 3.3 | 3 |

| Ratings from 1 to 5 | Relative Frequency (%) | Me | Md | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1 = Completely Disagree to 5 = Completely Agree) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| It is necessary to introduce the territorial cohesion approach in national and regional policies, paying particular attention to the challenges of depopulated rural areas. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 34.3 | 62.9 | 4.6 | 5 |

| There is a need for further normative development and coordination among public administrations in the fight against depopulation. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.6 | 34.3 | 57.1 | 4.5 | 5 |

| It is necessary to allocate a larger portion of national and regional policy funding to areas affected by depopulation, even at the expense of other policies. | 2.9 | 0.0 | 28.6 | 34.3 | 34.3 | 4.0 | 4 |

| Ratings from 1 to 5 | Relative Frequency (%) | Me | Md | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1 = Completely Disagree to 5 = Completely Agree) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Strategies aimed at digitization should pay special attention to supporting rural areas and the agri-food sector, bridging gaps with urban areas and other sectors. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 40.0 | 60.0 | 4.6 | 5 |

| The Next-Generation Recovery Funds should prioritize financing investments in rural areas and municipalities affected by depopulation. | 0.0 | 2.9 | 8.6 | 42.9 | 45.7 | 4.3 | 5 |

| Environmental strategies aimed at combating climate change, decarbonization, renewable energies, etc., should give special attention to supporting rural areas. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 17.1 | 51.4 | 31.4 | 4.1 | 4 |

| The “Plan of Measures for the Demographic Challenge” is an excellent starting point for the formulation of coordinated policies against depopulation. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 28.6 | 48.6 | 22.9 | 3.9 | 4 |

| Ratings from 1 to 5 | Relative Frequency (%) | Me | Md | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1 = Completely Disagree to 5 = Completely Agree) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1. The Spanish Strategic Plan for the Post-CAP accurately diagnoses the needs of the agricultural sector. | 2.9 | 5.7 | 31.4 | 45.7 | 14.3 | 3.6 | 4 |

| 2. The Spanish Strategic Plan for the Post-CAP accurately diagnoses the needs of the rural environment. | 2.9 | 2.9 | 51.4 | 31.4 | 11.4 | 3.5 | 3 |

| 3. In its design and implementation, as in other policies, the participation of key stakeholders is insufficient. | 8.6 | 14.3 | 8.6 | 40.0 | 25.7 | 3.6 | 4 |

| 4. The growth of resources allocated to the environment and climate action, in line with the European Green Deal, is positive for society as a whole. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 45.7 | 51.4 | 4.5 | 5 |

| 5. The increase in resources allocated to the environment and climate action, in line with the European Green Deal, is positive for the agricultural sector. | 0.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 54.3 | 40.0 | 4.3 | 4 |

| 6. The funds for Rural Development managed by Local Action Groups should be greater. | 0.0 | 8.6 | 25.7 | 28.6 | 37.1 | 3.9 | 4 |

| 7. The increase in bureaucracy and administrative burden associated with monitoring CAP aid is excessive. | 2.9 | 5.7 | 17.1 | 31.4 | 42.9 | 4.1 | 4 |

| 8. The increase in bureaucracy for Local Action Groups hampers their ability to revitalize territories. | 0.0 | 2.9 | 11.4 | 51.4 | 34.3 | 4.2 | 4 |

| Measures and Actions to Support Rural Areas Affected by Depopulation (1st = First or Most Important; 2nd = Second; 3rd = Third) | Relative Frequency (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | Total | |

| 1. Establish plans for the coverage of guaranteed basic public services in rural areas, including healthcare, education, and social services, comparable to those in urban areas. | 20.0 | 31.4 | 11.4 | 62.9 |

| 2. Implement incentives and support for the location and creation of businesses and employment in rural areas. | 17.1 | 14.3 | 5.7 | 37.1 |

| 3. Review the funding of local entities with criteria ensuring their subsistence and covering extra costs associated with providing basic services in small communities, reinforcing criteria for accessing lines and plans for smaller municipalities. | 14.3 | 8.6 | 14.3 | 37.1 |

| 4. Establish special support plans for self-employed individuals and entrepreneurs in rural areas, promoting training and employment, with special attention to young people and women. | 8.6 | 8.6 | 14.3 | 31.4 |

| 5. Explicitly include in the budgets of all Public Administrations (AAPP), a demographic strategy with annual objectives, means to achieve them, and an evaluation of achievements. | 17.1 | 2.9 | 5.7 | 25.7 |

| 6. Provide tax credits and deductions for professional and business activities carried out in rural areas or in personal income tax for residents. | 5.7 | 11.4 | 8.6 | 25.7 |

| 7. Provide support for childbirth, bonuses for families with children, or encourage the proximity of daycare services. | 2.9 | 2.9 | 5.7 | 11.4 |

| 8. Promote urban regeneration, rehabilitation plans, and access to housing for the population of small municipalities, creating housing opportunities, etc. | 0.0 | 8.6 | 2.9 | 11.4 |

| 9. Facilitate the decentralization of public care resources in the Autonomous Community (residences, youth centers, day centers, home assistance, etc.), supporting the creation of intermunicipal associations. | 0.0 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 11.4 |

| 10. Improve communication infrastructure based on a distance map to basic services and enhance public transportation services for the population of rural municipalities. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.4 | 11.4 |

| 11. Reinstate the 2007 Sustainable Rural Development Law, envisioned as a national framework with common and harmonized guidelines in the fight against depopulation in Spain, obliging the development of area plans as an intervention scale. | 5.7 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 8.6 |

| 12. Promote and support intermunicipal associations for social and public services. | 5.7 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 8.6 |

| 13. When implementing depopulation countermeasures at the national, regional, or autonomous community levels, clearly define the competence, whether unique or shared. | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 8.6 |

| 14. Improve digital infrastructure and implement ICT training plans in rural areas. | 0.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 5.7 |

| 15. Develop communication strategies to promote the advantages of rural areas, fostering identity. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Carrasco Pleite, F.; Colino Sueiras, J. Rural Depopulation in Spain: A Delphi Analysis on the Need for the Reorientation of Public Policies. Agriculture 2024, 14, 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14020295

Martínez-Carrasco Pleite F, Colino Sueiras J. Rural Depopulation in Spain: A Delphi Analysis on the Need for the Reorientation of Public Policies. Agriculture. 2024; 14(2):295. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14020295

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Carrasco Pleite, Federico, and José Colino Sueiras. 2024. "Rural Depopulation in Spain: A Delphi Analysis on the Need for the Reorientation of Public Policies" Agriculture 14, no. 2: 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14020295

APA StyleMartínez-Carrasco Pleite, F., & Colino Sueiras, J. (2024). Rural Depopulation in Spain: A Delphi Analysis on the Need for the Reorientation of Public Policies. Agriculture, 14(2), 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14020295