The Association of Socio-Economic Factors and Indigenous Crops on the Food Security Status of Farming Households in KwaZulu-Natal Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

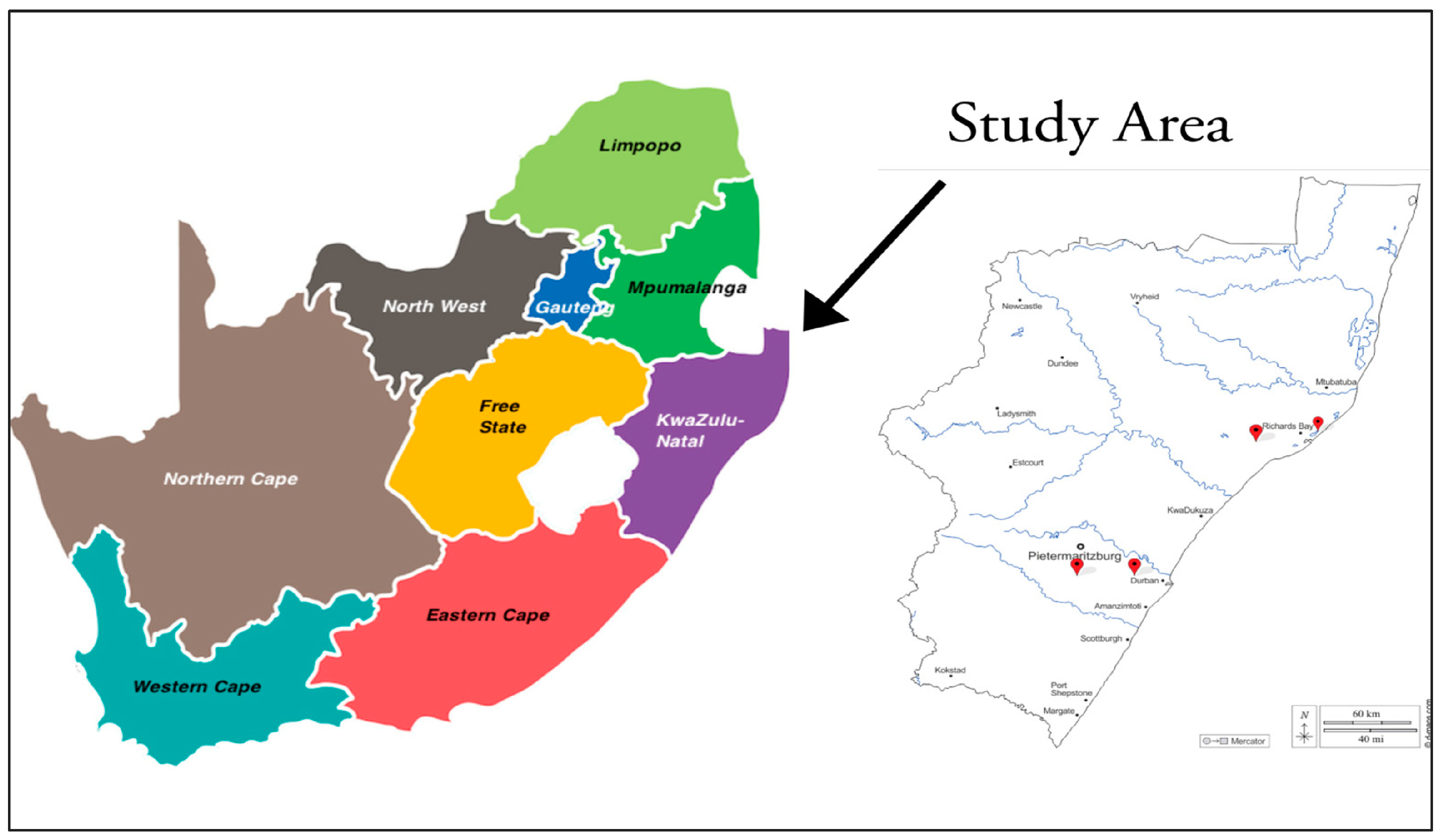

2.1. Description of the Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Extended Ordered Probit Regression to Determine the Association between Indigenous Crop Factors and Household Food Security

Pr {Qi = 2|Xi} = Φ (µ2 − Xiβ) − Φ (µ − Xiβ),

Pr {Qi = 3|Xi} = Φ (µ3 − Xiβ) − Φ (µ2 − Xiβ),

Pr {Qi = 4|Xi} = 1 − Φ (µ3 − Xiβ).

2.4.1. Justification for Proposed Variables

Indigenous Crop Access

Indigenous Crop Consumption

Farming Period

Indigenous Crops’ Perception

Required Assistance

Indigenous Crops’ Perceived Marketing Potential

Indigenous Crops Are a Suitable Marketing Channel

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Sampled Farming Households

3.2. Prevalence of Food (in)Security Amongst the Sampled Farming Households

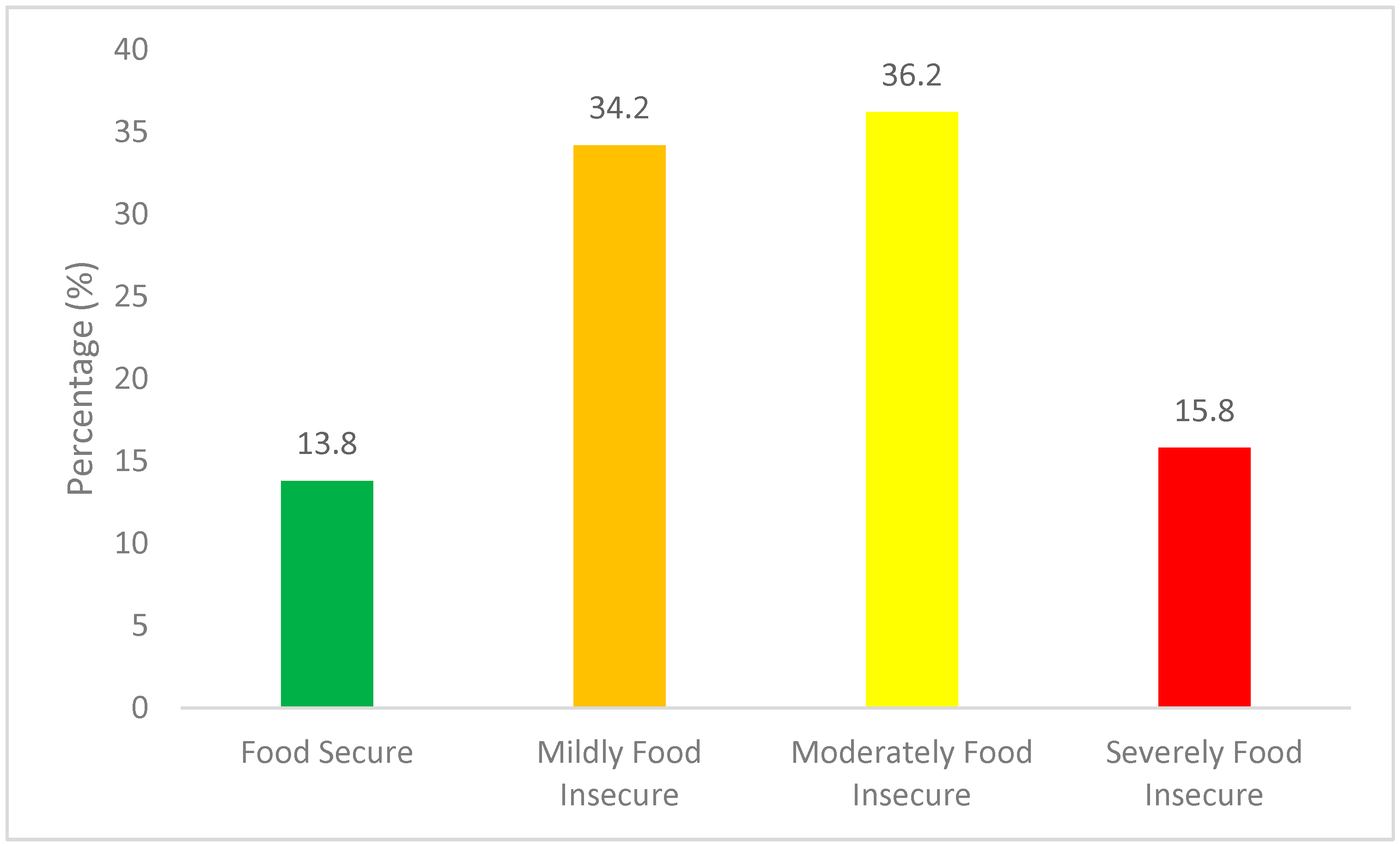

Food (in)Security Situation amongst the Farming Households

3.3. Factors Associated with Indigenous Crops and Their Contribution to Household Food Security

3.3.1. Association between Socio-Economic Parameters and Household Food *(in)Security

3.3.2. Factors Associated with Indigenous Crops and Household Food Security

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Magadze, A.A.; Obadire, O.S.; Maliwichi, L.L.; Musyoki, A.; Mbhatsani, H.V. An assessment of types of foods consumed by individuals in selected households in South Africa. Gend. Behav. 2017, 15, 10610–10626. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, M.; Muchesa, E.; Kroll, F. Use of urban agriculture in addressing health disparities and promotion of ecological health in South Africa. Curr. Health 2020, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndhleve, S.; Dapira, C.; Kabiti, H.M.; Mpongwana, Z.; Cishe, E.N.; Nakin, M.D.V.; Shisanya, S.; Walker, K.P. Household Food Insecurity Status and Determinants: The Case of Botswana and South Africa. AGRARIS J. Agribus. Rural Dev. Res. 2021, 7, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Haese, M.; Vink, N.; Nkunzimana, T.; Van Damme, E.; Van Rooyen, J.; Remaut, A.M.; Staelens, L.; d’Haese, L. Improving food security in the rural areas of KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa: Too little, too slow. Dev. S. Afr. 2013, 30, 468–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuku, M.; Selepe, M.; Ngcobo, N. Status of household food security in rural areas at UThingulu District, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2017, 6, 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Naicker, N.; Mathee, A.; Teare, J. Food insecurity in households in informal settlements in urban South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2015, 105, 268–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, D.F. An Assessment of the Importance of the Agricultural Sector on Economic Growth and Development in South Africa. In Proceedings of the International Academic Conferences 2019 October (No. 9912288), Barcelona, Spain, 23–26 September 2019; International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, S. Agriculture and agrarian change in South Africa. In The Geography of South Africa: Contemporary Changes and New Directions; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Oluwatayo, I.B.; Mantsho, S.M. Budgetary allocation to agriculture in South Africa: An empirical review from 1994 to 2014. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2016, 14, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ransom, E. The Political Economy of Agriculture in Southern Africa; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mazvimavi, K. Socio-Economic Analysis of Conservation Agriculture in Southern Africa; FAO Regional Emergency Office for Southern Africa (REOSA): Johannesburg, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Raphela, T.D.; Pillay, N. Quantifying the nutritional and income loss caused by crop raiding in a rural African subsistence farming community in South Africa. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2021, 13, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayemi, B.; Nirmala, D. Creating economic viability in rural South Africa through water resource management in subsistence farming. Environ. Econ. 2016, 7, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jacobs, P.T. The status of household food security targets in South Africa. Agrekon 2009, 48, 410–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; O’Reilly, P.; Walker, S.; Mwale, S. Opportunities for underutilised crops in southern Africa’s post–2015 development agenda. Sustainability 2016, 8, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, K. Agrobiodiversity: The living library. Nature 2017, 544, S8–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chivenge, P.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Modi, A.T.; Mafongoya, P. The potential role of neglected and underutilised crop species as future crops under water scarce conditions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 5685–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngcoya, M.; Kumarakulasingam, N. The lived experience of food sovereignty: Gender, indigenous crops, and small-scale farming in Mtubatuba, South Africa. J. Agrar. Chang. 2017, 17, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, J.D.; Cloete, P.C.; Van der Hoeven, M. Promoting food security through indigenous and traditional food crops. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2016, 40, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, H.L.; Hollington, P.A.; Pasquini, M.W.; Chiappini, C.P. How can we remove barriers to increased usage of indigenous crops? Acta Hortic. 2015, 1102, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matenge, S.T.; Van der Merwe, D.; Kruger, A.; De Beer, H. Utilisation of indigenous plant foods in the urban and rural communities. Indilinga Afr. J. Indig. Knowl. Syst. 2011, 10, 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Malkanthi, S.H.; Karunaratne, A.S.; Amuwala, S.D.; Silva, P. Opportunities and challenges in cultivating underutilized field crops in Moneragala district of Sri Lanka. Asian J. Agric. Rural Dev. 2014, 4, 96–105. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, S. Field to Fork: Challenges in Ensuring a Sustainable Food Supply. Johns. Matthey Technol. Rev. 2018, 62, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, O.O. Contribution of neglected and underutilized crops to household food security and health among rural dwellers in Oyo State, Nigeria. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Underutilized Plants for Food Security, Nutrition, Income and Sustainable Development 806, Arusha, Tanzania, 3–7 March 2008; pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Backeberg, G.R.; Water, A.S. Underutilised indigenous and traditional crops: Why is research on water use important for South Africa? S. Afr. J. Plant Soil 2010, 27, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndhleve, S.; Obi, A.; Nakin, M.D.V. Public spending on agriculture and poverty in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Afr. Stud. Q. 2017, 17, 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Von Loeper, W.; Musango, J.; Brent, A.; Drimie, S. Analysing challenges facing smallholder farmers and conservation agriculture in South Africa: A system dynamics approach. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2016, 19, 747–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modirwa, S.; Oladele, O.I. Food security among male and female-headed households in Eden District Municipality of the Western Cape, South Africa. J. Hum. Ecol. 2012, 37, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibesigwa, B.; Visser, M. Small-Scale Subsistence Farming, Food Security, Climate Change and Adaptation in South Africa: Male-Female Headed Households and Urban-Rural Nexus; Economic Research Southern Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, T.; Aliber, M. Inequalities in Agricultural Support for Women in South Africa. 2012. Available online: https://repository.hsrc.ac.za/handle/20.500.11910/3235 (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Sharaunga, S.; Mudhara, M. Analysis of livelihood strategies for reducing poverty among rural women’s households: A case study of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J. Int. Dev. 2021, 33, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokgomo, M.N.; Chagwiza, C.; Tshilowa, P.F. The impact of government agricultural development support on agricultural income, production and food security of beneficiary small-scale farmers in South Africa. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshikororo, M.; Baloyi, S.; Gwebu, M.P. Influence of Farming Experience and Knowledge on Selection of Climate Change Resilient Strategies among Female Agripreneurs in the Mopani of Limpopo Province South Africa. J. Agric. Ext. 2024, 28, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondi, N.T.B.; Ngidi, M.S.C.; Ojo, T.O.; Hlatshwayo, S.I. Impact of Market Participation of Indigenous Crops on Household Food Security of Smallholder Farmers of South Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyolo, G.M.; Wale, E.; Ortmann, G.F. Analysing the value chain for African leafy vegetables in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1509417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloete, P.C.; Idsardi, E. Bio-Fuels and Food Security in South Africa: The Role of Indigenous and Traditional Food Crops. 2012. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/130172/ (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Chibarabada, T.P.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Murugani, V.G.; Pereira, L.M.; Sobratee, N.; Govender, L.; Slotow, R.; Modi, A.T. Mainstreaming underutilized indigenous and traditional crops into food systems: A South African perspective. Sustainability 2018, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leakey, R.R.; Tientcheu Avana, M.L.; Awazi, N.P.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Hendre, P.S.; Degrande, A.; Hlahla, S.; Manda, L. The future of food: Domestication and commercialization of indigenous food crops in Africa over the third decade (2012–2021). Sustainability 2022, 14, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, A.T. What do subsistence farmers know about indigenous crops and organic farming? Preliminary experience in KwaZulu-Natal. Dev. S. Afr. 2003, 20, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulu, S.S.; Ngidi, M.; Ojo, T.; Hlatshwayo, S.I. Determinants of consumers’ acceptance of indigenous leafy vegetables in Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces of South Africa. J. Ethn. Foods 2022, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwazulu-Natal Municipalities. Municipal Directories and Reports; Government of South Africa. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.za/about-government/contact-directory (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Jilajila, S.P.; Ngidi, M.S.C.; Hlatshwayo, S.I.; Ojo, T.O. An Analysis of the Prevalence and Factors Influencing Food Insecurity among University Students Participating in Alcohol Consumption in KwaZulu-Natal Province. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooldridge, J. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; Volume 16, 1096p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Ordinal regression analysis: Fitting the proportional odds model using Stata, SAS, and SPSS. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2009, 8, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D.N.; Potter, D.C. Basic Econometrics, 5th ed.; The McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mudzielwana, R.; Mafongoya, P.; Mudhara, M. An Analysis of the Determinants of Irrigation Farmworkers’ Food Security Status: A Case of Tshiombo Irrigation Scheme, South Africa. Agriculture 2022, 12, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gido, E.O.; Ayuya, O.I.; Owuor, G.; Bokelmann, W. Consumption intensity of leafy African indigenous vegetables: Towards enhancing nutritional security in rural and urban dwellers in Kenya. Agric. Food Econ. 2017, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuku, M.M.; Bhengu, A.S. The value of indigenous foods in improving food security in Emaphephetheni rural setting. Indilinga Afr. J. Indig. Knowl. Syst. 2021, 20, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ekesa, B.N.; Walingo, M.K.; Onyango, M.O. Accessibility to and consumption of indigenous vegetables and fruits by rural households in Matungu division, western Kenya. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2009, 9, 1725–1738. [Google Scholar]

- Sekhampu, T.J. Association of food security and household demographics in a South African township. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Stud. 2017, 9, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Oduniyi, O.S.; Tekana, S.S. Status and socio-economic determinants of farming households’ food security in Ngaka Modiri Molema District, South Africa. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 149, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweba, T.P.; Mearns, M.A. Conserving indigenous knowledge as the key to the current and future use of traditional vegetables. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayekiso, A.; Taruvinga, A.; Mushunje, A. Perceptions and determinants of smallholder farmers’ participation in the production of indigenous leafy vegetables: The case of Coffee Bay, Eastern Cape province of South Africa. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2017, 9, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hoeven, M.; Osei, J.; Greeff, M.; Kruger, A.; Faber, M.; Smuts, C.M. Indigenous and traditional plants: South African parents’ knowledge, perceptions and uses and their children’s sensory acceptance. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raidimi, E.N.; Kabiti, H.M. Agricultural extension, research, and development for increased food security: The need for public-private sector partnerships in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 2017, 45, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfamariam, B.Y.; Owusu-Sekyere, E.; Emmanuel, D.; Elizabeth, T.B. The impact of the homestead food garden programme on food security in South Africa. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Agyei, P.; Stringer, L.C. Improving the effectiveness of agricultural extension services in supporting farmers to adapt to climate change: Insights from northeastern Ghana. Clim. Risk Manag. 2021, 32, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinola, R.; Pereira, L.M.; Mabhaudhi, T.; De Bruin, F.M.; Rusch, L. A review of indigenous food crops in Africa and the implications for more sustainable and healthy food systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, A.O.; Aremu, A.O. Evaluation of factors influencing the inclusion of indigenous plants for food security among rural households in the North West Province of South Africa. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngidi, M.S.C.; Zulu, S.S.; Ojo, T.O.; Hlatshwayo, S.I. Effect of Consumers’ Acceptance of Indigenous Leafy Vegetables and Their Contribution to Household Food Security. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Chimonyo, V.G.; Modi, A.T. Status of underutilised crops in South Africa: Opportunities for developing research capacity. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marson, M.; Vaggi, G. Sustainable Value Chains in Agriculture. The African Indigenous Vegetables in Southern Nakuru County (No. 174). University of Pavia, Department of Economics and Management, 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marta-Marson/publication/336891159_Sustainable_value_chains_in_agriculture_The_African_Indigenous_Vegetables_in_Southern_Nakuru_County/links/5db94b81a6fdcc2128ebe760/Sustainable-value-chains-in-agriculture-The-African-Indigenous-Vegetables-in-Southern-Nakuru-County.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Abegunde, V.O.; Sibanda, M.; Obi, A. Determinants of the adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices by small-scale farming households in King Cetshwayo District Municipality, South Africa. Sustainability 2019, 12, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.L.; Reynolds, T.W.; Biscaye, P.; Patwardhan, V.; Schmidt, C. Economic benefits of empowering women in agriculture: Assumptions and evidence. J. Dev. Stud. 2021, 57, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlatshwayo, S.I.; Ojo, T.O.; Modi, A.T.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Slotow, R.; Ngidi, M.S.C. The determinants of market participation and its effect on food security of the rural smallholder farmers in Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces, South Africa. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipfupa, U.; Tagwi, A. Youth’s participation in agriculture: A fallacy or achievable possibility? Evidence from rural South Africa. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2021, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Quartely Labour Force Report. 2021. Available online: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/Presentation%20QLFS%20Q42021.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Ryckman, T.; Beal, T.; Nordhagen, S.; Chimanya, K.; Matji, J. Affordability of nutritious foods for complementary feeding in Eastern and Southern Africa. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79 (Suppl. S1), 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics South Africa. 2011. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03014/P030142011.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Statistics South Africa. 2016. Available online: http://cs2016.statssa.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/KZN.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Thornton, A.J. Dietary Diversity and Food Security in South Africa: An Application Using NIDS Wave 1. Master’s Thesis, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunlela, Y.I.; Mukhtar, A.A. Gender issues in agriculture and rural development in Nigeria: The role of women. Humanit. Soc. Sci. J. 2009, 4, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pelekamoyo, J.; Umar, B.B. Access to and control over agricultural labor and income in smallholder farming households: A gendered look from Chipata, Eastern Zambia. J. Gend. Agric. Food Secur. Agri-Gend. 2019, 4, 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hlatshwayo, S.I.; Ngidi, M.; Ojo, T.; Modi, A.T.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Slotow, R. A typology of the level of market participation among smallholder farmers in South Africa: Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baiphethi, M.N.; Jacobs, P.T. The contribution of subsistence farming to food security in South Africa. Agrekon 2009, 48, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbatha, M.W.; Mnguni, H.; Mubecua, M.A. Subsistence farming as a sustainable livelihood approach for rural communities in South Africa. Afr. J. Dev. Stud. 2021, 11, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Chakona, G.; Shackleton, C.M. Food insecurity in South Africa: To what extent can socially grants and consumption of wild foods eradicate hunger? World Dev. Perspect. 2019, 13, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imathiu, S. Neglected and underutilized cultivated crops with respect to indigenous African leafy vegetables for food and nutrition security. J. Food Secur. 2021, 9, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijatuyi, E.J.; Omotayo, A.O.; Nkonki-Mandleni, B. Empirical analysis of food security status of agricultural households in the platinum province of South Africa. J. Agribus. Rural. Dev. 2018, 47, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutengwa, C.S.; Mnkeni, P.; Kondwakwenda, A. Climate-Smart Agriculture and Food Security in Southern Africa: A Review of the Vulnerability of Smallholder Agriculture and Food Security to Climate Change. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naicker, M.; Naidoo, D.; Ngidi, M. Assessing the Impact of Community Gardens in Mitigating Household Food Insecurity and Addressing Climate Change Challenges: A Case Study of Ward 18, Umdoni Municipality, South Africa. Afr. J. Inter/Multidiscip. Stud. 2023, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nata, J.T.; Mjelde, J.W.; Boadu, F.O. Household adoption of soil-improving practices and food insecurity in Ghana. Agric. Food Security 2014, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Proposed Variable | Type of Measurement | Definition | Hypothesised Effect on HFIAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependant Variable | |||

| Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (Extended Ordered Regression) | |||

| Independent variables | |||

| Indigenous crop access | Categorical | 0 = Cultivation from own garden, 1 = Cultivation from cultivated lands from other farmers/gardens, 2 = Collection from wild velds or forests | − |

| Indigenous crop consumption | Categorical | 0 = Yes and 1 = No. | − |

| Farming period | Categorical | 0 = Under 4 years, 1 = 4 to 10 years, 2 = 10 to 20 years, and 3 = Greater than 20 years. | +/− |

| Indigenous crops’ perception | Categorical | 0 = old women; 1 = old men; 2 = young women; 3 = young men; 4 = everyone | +/− |

| Required farm assistance | Categorical | 0 = Seeds, 1 = Garden tools, 2 = Fencing, 3 = Shielding net, and 4 = Soil analysis | − |

| Indigenous crops’ perceived marketing potential | Categorical | 0 = Yes and 1 = No | +/− |

| Indigenous crops are a suitable marketing channel | Categorical | 0 = Local market only, 1 = Informal market only, 2 = Formal market only, and 3 = All markets | +/− |

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | Variable | Frequency(n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Marital Status | ||||

| Male | 95 | 36.5 | Married | 115 | 44.2 |

| Female | 165 | 63.5 | Unmarried | 145 | 55.8 |

| Age (Years) | Employment Status | ||||

| 18–24 | 28 | 10.8 | Unemployed | 98 | 37.7 |

| 25–34 | 43 | 16.5 | Full time | 41 | 15.8 |

| 35–44 | 48 | 18.5 | Part-time | 28 | 10.8 |

| 45–54 | 44 | 16.9 | Informal | 5 | 1.9 |

| 55–64 | 39 | 15.0 | Grant/Pension recipient | 85 | 32.7 |

| 65+ | 58 | 22.3 | Self-employed | 3 | 1.1 |

| Total Household monthly income | Education Level | ||||

| R0–R500 | 48 | 18.5 | None | 11 | 4.2 |

| R501–R1000 | 48 | 18.5 | Primary | 71 | 27.3 |

| R1001–R1500 | 45 | 17.3 | Secondary | 144 | 55.4 |

| R1501–R2500 | 40 | 15.4 | Tertiary | 34 | 13.1 |

| R2501–R3500 | 25 | 9.6 | |||

| R3501–R4500 | 30 | 11.5 | |||

| >R4500 | 24 | 9.2 | |||

| HFIAS Occurrence Questions In the Past 30 Days, Did You or Any Member of the Household: | Frequency of Occurrence (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Rarely (1–2 Times) | Sometimes (3–10 Times) | Often (More Than 10 Times) | |

| Worry about not having enough food | 65.8 | 34.2 | 47.9 | 37.4 | 14.6 |

| Not able to eat the kinds of foods you preferred | 77.7 | 22.3 | 28.7 | 40.1 | 31.2 |

| Have to eat a limited variety of foods | 68.1 | 31.9 | 46.9 | 24.3 | 28.8 |

| Have to eat some foods that you really did not want to eat | 76.9 | 23.1 | 30.0 | 42.5 | 27.5 |

| Have to eat smaller meals than you felt you needed | 66.2 | 33.8 | 34.9 | 34.6 | 12.8 |

| Have to eat fewer meals in a day | 70.0 | 30.0 | 36.3 | 49.5 | 14.3 |

| Ever had no food to eat of any kind in your household? Go to sleep at night hungry | 49.2 | 50.4 | 49.2 | 33.6 | 17.2 |

| 40.4 | 59.2 | 26.7 | 61.9 | 11.4 | |

| Go a whole day and night without eating anything | 41.9 | 58.1 | 27.5 | 61.5 | 5.5 |

| Demographics | Food-Secure | Mildy Food-Insecure | Moderately Food-Insecure | Severely Food-Insecure | X2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 9 | 41 | 28 | 16 | 0.057 * |

| Female | 27 | 48 | 66 | 25 | |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 19 | 38 | 41 | 17 | 0.904 |

| Unmarried | 17 | 51 | 53 | 24 | |

| Number of HH members | 36 | 89 | 94 | 41 | 0.051 * |

| Employment Status | |||||

| Unemployed | 15 | 32 | 35 | 16 | 0.608 |

| Employed | 12 | 34 | 21 | 10 | |

| Grant recipient | 9 | 23 | 38 | 15 | |

| HH Monthly income | |||||

| R0 to R500 | 5 | 11 | 11 | 5 | 0.059 * |

| R501 to R1000 | 3 | 21 | 34 | 16 | |

| R1001 to R1500 | 11 | 20 | 28 | 6 | |

| R1501 to R2500 | 5 | 13 | 7 | 3 | |

| R2501 to R3500 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| R3501 to R4500 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 2 | |

| >R4500 | 5 | 13 | 3 | 5 | |

| Educational Level | |||||

| None | 5 | 9 | 15 | 7 | 0.525 |

| Primary | 9 | 22 | 20 | 10 | |

| Secondary | 15 | 50 | 57 | 22 | |

| Tertiary | 7 | 13 | 8 | 6 |

| Variables | Coefficient | S. E | p > z |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous crop access | |||

| Collection from own garden | (Base) | ||

| Collection from cultivated lands | −0.027 | 0.249 | 0.913 |

| Collection from wild veld or forest | −0.388 | 0.283 | 0.170 |

| Indigenous crop consumption | |||

| Yes | (Base) | ||

| No | 1.174 | 0.468 | 0.012 ** |

| Farming Period | |||

| Under 4 years | (Base) | ||

| 4 to 10 years | −1.015 | 0.293 | 0.001 *** |

| 10 to 20 years | −1.117 | 0.318 | 0.000 *** |

| Greater than 20 years | −1.164 | 0.332 | 0.000 *** |

| Indigenous crops’ perception | |||

| Old women | (Base) | ||

| Old men | −0.006 | 0.278 | 0.983 |

| Young men | −1.344 | 0.454 | 0.003 *** |

| Everyone | −1.083 | 0.237 | 0.000 *** |

| Indigenous crops’ marketing potential | |||

| Yes | (Base) | ||

| No | −0.400 | 0.183 | 0.029 ** |

| Perceived suitable marketing channel | |||

| Local market only | (Base) | ||

| Informal market | 0.845 | 0.435 | 0.052 * |

| Formal market | −0.956 | 0.363 | 0.008 *** |

| All markets | 1.041 | 0.211 | 0.000 *** |

| Required Assistance | |||

| Seeds | (Base) | ||

| Garden tools | 0.091 | 0.354 | 0.796 |

| Fencing | −0.286 | 0.254 | 0.260 |

| Soil analysis | 1.060 | 0.404 | 0.009 *** |

| Irrigation | 1.423 | 0.688 | 0.038 ** |

| HFIAS CATEGORIES | |||

| cut1 | −2.988 | 0.436 | |

| cut2 | −1.223 | 0.409 | |

| cut3 | 0.199 | 0.390 | |

| Log-likelihood | −192.724 | ||

| Wald chi2 | 83.180 | ||

| Prob > Chi2 | 0.000 *** | ||

| Akaike’s information criterion | 425.443 | ||

| Bayesian information criterion | 490.598 | ||

| Mean VIF | 1.88 |

| Categorical | Variables | Food Secure | Mildly Food Insecure | Moderately Food Insecure | Severely Food Insecure | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | Standard Error | p > z | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | p > z | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | p > z | Odds Ration | Standard Error | p > z | ||

| Indigenous Crop Access | Own Garden | Base | |||||||||||

| Cultivated Lands | 0.003 | 0.031 | 0.913 | 0.004 | 0.041 | 0.913 | −0.003 | 0.027 | 0.913 | −0.005 | 0.045 | 0.914 | |

| Collection from wild velds or forests | 0.057 | 0.043 | 0.189 | 0.055 | 0.038 | 0.148 | −0.051 | 0.037 | 0.171 | −0.061 | 0.044 | 0.169 | |

| Consumption of Indigenous Crops | Yes | Base | |||||||||||

| No | −0.094 | 0.024 | 0.000 *** | −0.217 | 0.082 | 0.008 *** | 0.047 | 0.032 | 0.140 | 0.265 | 0.125 | 0.034 ** | |

| Farming Period | Under 4 years | Base | |||||||||||

| 4 to 10 years | 0.088 | 0.024 | 0.000 *** | 0.190 | 0.056 | 0.001 *** | −0.053 | 0.022 | 0.015 ** | −0.225 | 0.073 | 0.002 *** | |

| 10 to 20 years | 0.103 | 0.031 | 0.001 *** | 0.204 | 0.058 | 0.000 *** | −0.067 | 0.028 | 0.019 ** | −0.241 | 0.075 | 0.001 *** | |

| >20 years | 0.111 | 0.035 | 0.002 *** | 0.210 | 0.059 | 0.000 *** | −0.073 | 0.030 | 0.014 ** | −0.247 | 0.076 | 0.001 *** | |

| Perception of Indigenous Crops | Old women | Base | |||||||||||

| Old men | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.983 | 0.001 | 0.064 | 0.983 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.983 | −0.001 | 0.069 | 0.983 | |

| Young men | 0.197 | 0.096 | 0.041 ** | 0.216 | 0.049 | 0.000 *** | −0.221 | 0.087 | 0.011 ** | −0.192 | 0.052 | 0.000 *** | |

| Everyone | 0.139 | 0.034 | 0.000 *** | 0.201 | 0.048 | 0.000 *** | −0.166 | 0.039 | 0.000 *** | −0.175 | 0.046 | 0.000 *** | |

| Required Assistance | Seeds | Base | |||||||||||

| Garden Tools | −0.012 | 0.046 | 0.789 | −0.015 | 0.059 | 0.804 | 0.012 | 0.045 | 0.791 | 0.015 | 0.060 | 0.802 | |

| Fencing | 0.046 | 0.044 | 0.295 | 0.037 | 0.030 | 0.212 | −0.043 | 0.040 | 0.282 | −0.040 | 0.033 | 0.228 | |

| Soil Analysis | −0.084 | 0.023 | 0.000 *** | −0.211 | 0.081 | 0.009 *** | 0.059 | 0.236 | 0.012 ** | 0.236 | 0.107 | 0.028 ** | |

| Irrigation | −0.093 | 0.023 | 0.000 *** | −0.279 | 0.119 | 0.019 ** | 0.032 | 0.074 | 0.666 | 0.340 | 0.200 | 0.089 * | |

| Indigenous crops’ perceived marketing potential | Yes | Base | |||||||||||

| No | 0.052 | 0.023 | 0.026 ** | 0.067 | 0.034 | 0.047 ** | −0.050 | 0.024 | 0.041 ** | −0.069 | 0.032 | 0.033 ** | |

| Indigenous crops’ perceived marketing channels | Local Market Only | Base | |||||||||||

| Informal Market Only | −0.117 | 0.046 | 0.010 ** | −0.131 | 0.090 | 0.146 | 0.114 | 0.047 | 0.015 ** | 0.134 | 0.086 * | 0.120 | |

| Formal Market Only | 0.244 | 0.100 | 0.014 ** | −0.031 | 0.047 | 0.511 | −0.152 | 0.049 | 0.002 *** | −0.061 | 0.021 ** | 0.004 *** | |

| All market | −0.132 | 0.032 | 0.000 *** | −0.173 | 0.038 | 0.000 *** | 0.126 | 0.031 | 0.000 *** | 0.179 | 0.037 ** | 0.000 *** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shelembe, N.; Hlatshwayo, S.I.; Modi, A.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Ngidi, M.S.C. The Association of Socio-Economic Factors and Indigenous Crops on the Food Security Status of Farming Households in KwaZulu-Natal Province. Agriculture 2024, 14, 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14030415

Shelembe N, Hlatshwayo SI, Modi A, Mabhaudhi T, Ngidi MSC. The Association of Socio-Economic Factors and Indigenous Crops on the Food Security Status of Farming Households in KwaZulu-Natal Province. Agriculture. 2024; 14(3):415. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14030415

Chicago/Turabian StyleShelembe, Nomfundo, Simphiwe Innocentia Hlatshwayo, Albert Modi, Tafadzwanashe Mabhaudhi, and Mjabuliseni Simon Cloapas Ngidi. 2024. "The Association of Socio-Economic Factors and Indigenous Crops on the Food Security Status of Farming Households in KwaZulu-Natal Province" Agriculture 14, no. 3: 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14030415

APA StyleShelembe, N., Hlatshwayo, S. I., Modi, A., Mabhaudhi, T., & Ngidi, M. S. C. (2024). The Association of Socio-Economic Factors and Indigenous Crops on the Food Security Status of Farming Households in KwaZulu-Natal Province. Agriculture, 14(3), 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14030415