The Influence and Mechanism of Digital Village Construction on the Urban–Rural Income Gap under the Goal of Common Prosperity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

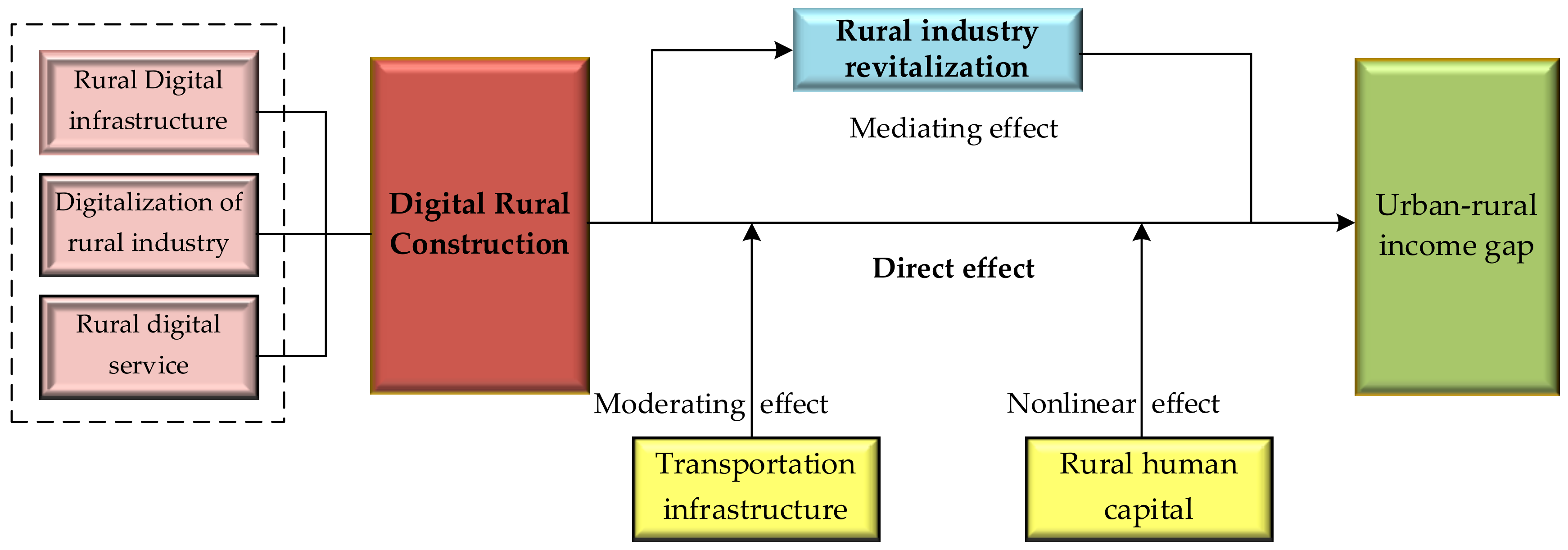

2. Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Analysis of the Influence of Digital Village Construction on Urban–Rural Income Gap

2.2. Analysis of the Mediating Mechanism of Digital Village Construction and the Urban–Rural Income Gap

2.3. Analysis of the Moderate Mechanism of Digital Village Construction Affecting the Urban–Rural Income Gap

2.4. The Non-Linear Influence of Digital Village Construction and Urban–Rural Income Gap under the Human Capital Perspective

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of Variables

3.1.1. Dependent Variable

3.1.2. Independent Variable

3.1.3. Core Explanatory Variable

3.1.4. Control Variables

3.2. Model Setting

3.2.1. Panel Data Models

3.2.2. Mediating-Effect Model

3.2.3. Moderate Effect Model

3.2.4. Threshold Model

3.3. Data Sources

4. Results and Discussion

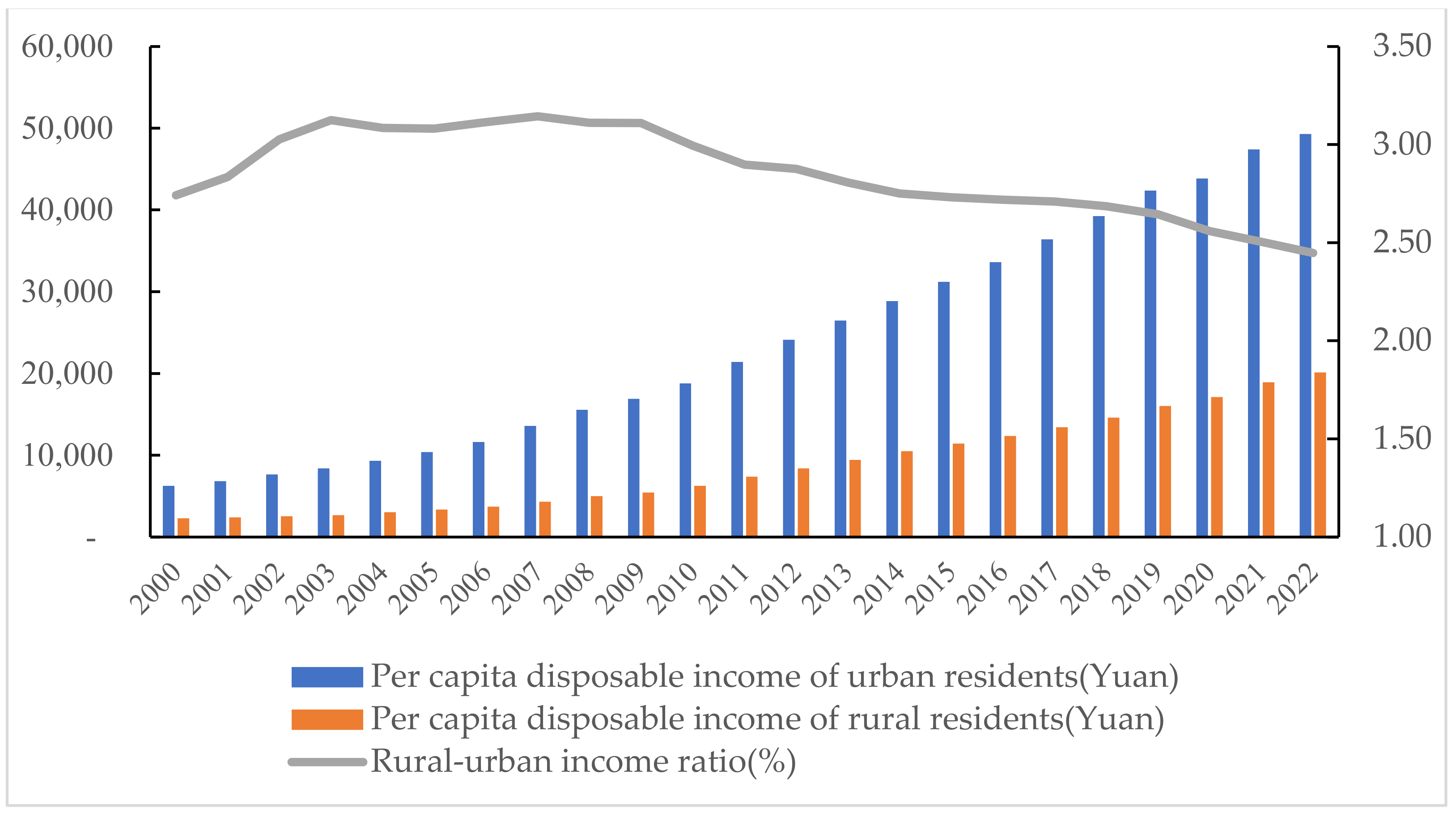

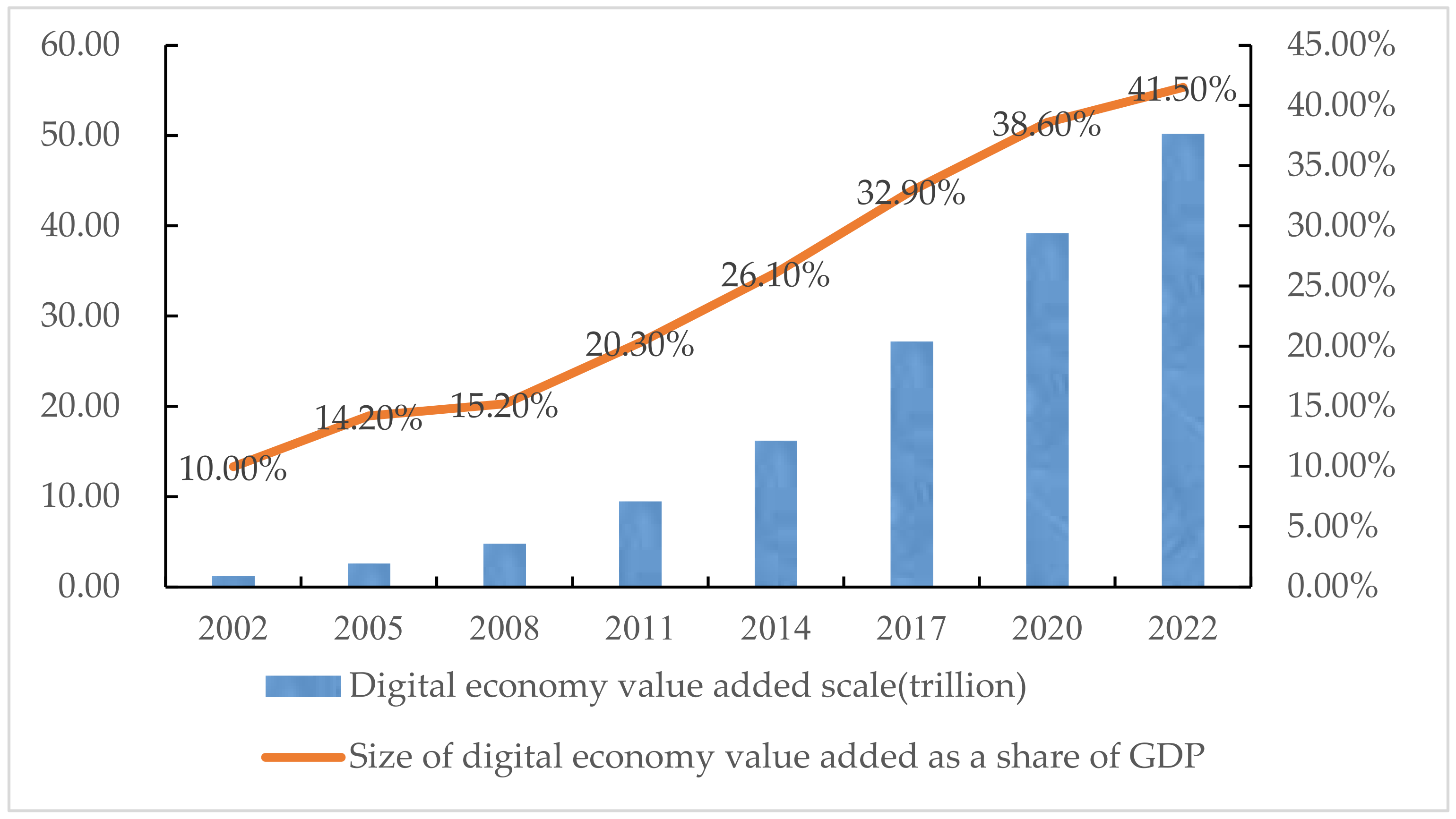

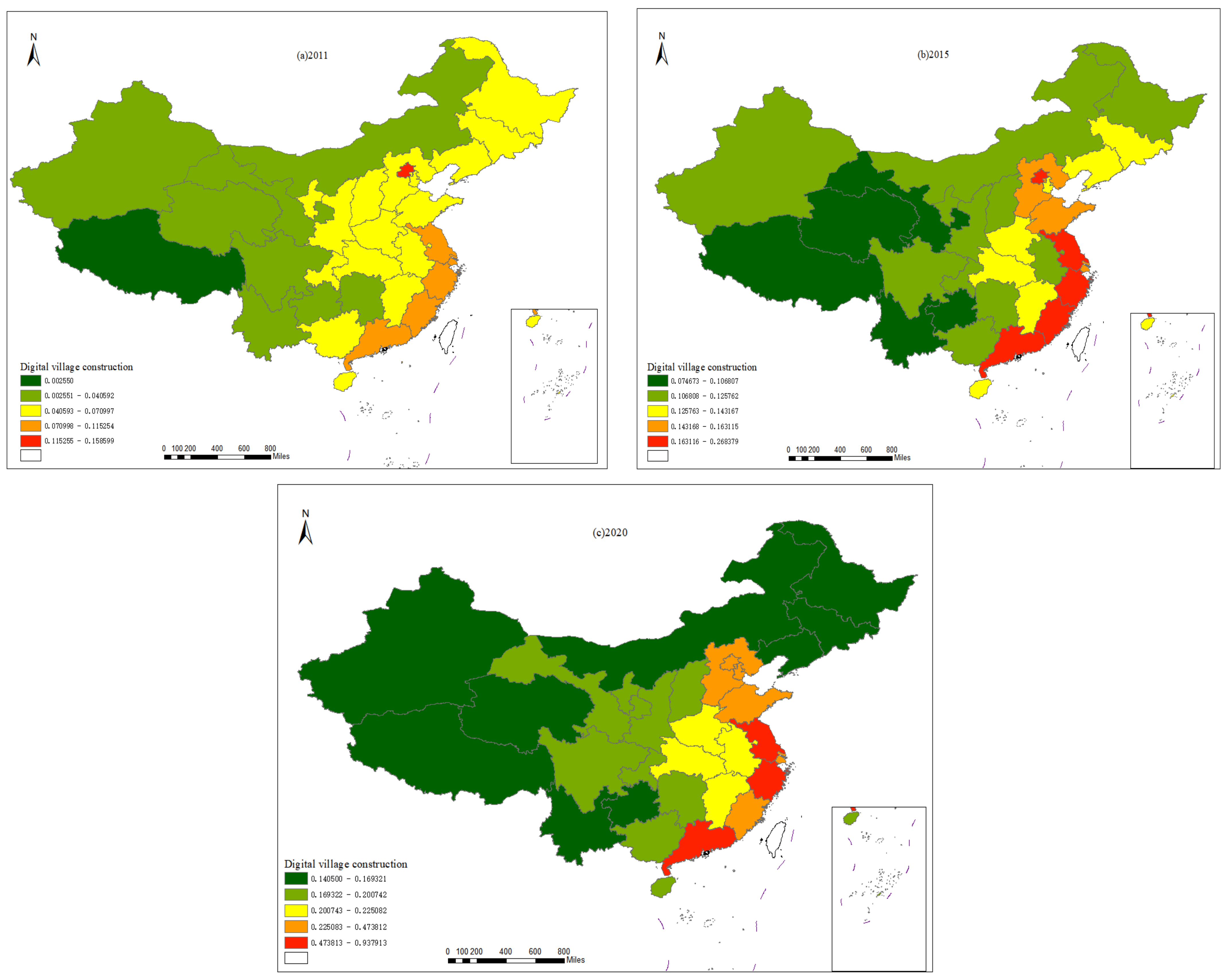

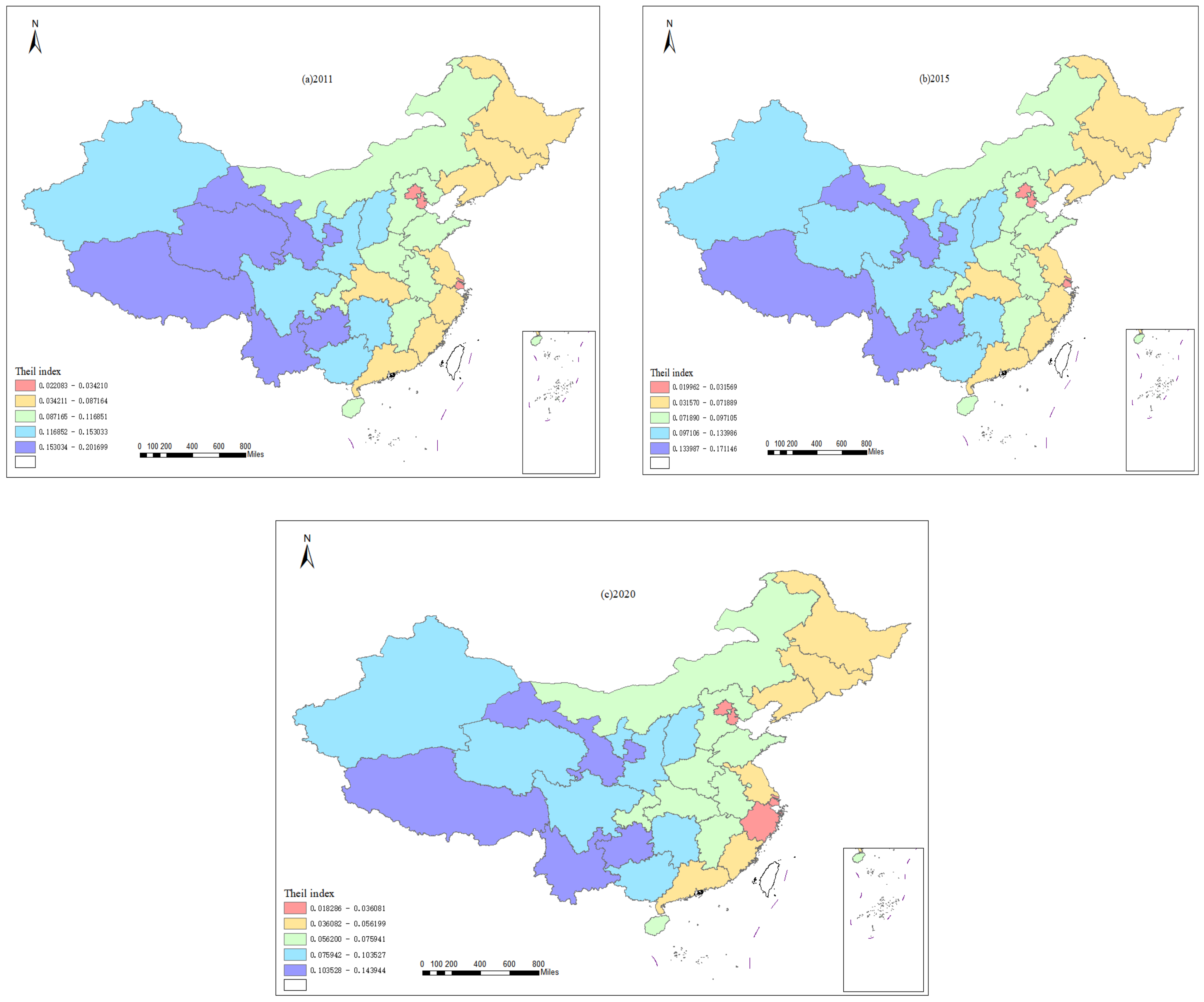

4.1. Annual Change Characteristics of Digital Village Construction and Urban–Rural Income Gap

4.2. Benchmark Regression Results

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.4. Mechanism Analysis

4.5. Threshold Model Analysis

4.6. Heterogeneity Tests

5. Conclusions and Suggestion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Huang, Z.; Fan, B. Overcoming the middle-income trap: International experiences and China’s choice. China Econ. J. 2021, 14, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Cheng, L.; Lin, Q.; He, Q. Promoting or inhibiting: The impact of China’s urban-rural digital divide on regional environmental development. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 112710–112724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.C.; Zeng, M.; Luo, K. Food security and digital economy in China: A pathway towards sustainable development. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 78, 1106–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesco, S.; Sambo, P.; Borin, M.; Basso, B.; Orzes, G.; Mazzetto, F. Smart agriculture and digital twins: Applications and challenges in a vision of sustainability. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 146, 126809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Wen, Q.; Geng, X. Consumer preferences for agricultural product brands in an E-commerce environment. Agribusiness 2022, 38, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Rao, X.; Lin, Q. Study of the impact of digitization on the carbon emission intensity of agricultural production in China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 903, 166544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, M.; Tian, M.; Wang, J. The impact of digital economy on green development of agriculture and its spatial spillover effect. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2023, 15, 708–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. The role of digital finance in reducing agricultural carbon emissions: Evidence from China’s provincial panel data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 87730–87745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, E. Analyzing collective action. Agrecon 2010, 41, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.; Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, K. Impact of digital economy development on carbon emission intensity in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region: A mechanism analysis based on industrial structure optimization and green innovation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 41644–41664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.K.; Singh, R.; Gehlot, A.; Akram, S.V.; Das, P.K. Village 4.0: Digitalization of village with smart internet of things technologies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 165, 107938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Mu, Y.; Zhang, W. Digital inclusive financial services and rural income: Evidence from China’s major grain-producing regions. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 53, 103622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, M. Does digital inclusive finance promote agricultural production for rural households in China? Research based on the Chinese family database (CFD). China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2021, 13, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, J. Digital Revolution and Employment Choice of Rural Labor Force: Evidence from the Perspective of Digital Skills. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, Z. The impact of industrial structure upgrades on the urban–rural income gap: An empirical study based on China’s provincial panel data. Growth Change 2021, 52, 1761–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, H. Digital village construction and farmers’ income growth: Theoretical mechanism and micro experience based on data from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, S. The Road to Common Prosperity: Can the digital village construction Increase Household Income? Sustainability 2023, 15, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, H.; Li, J.; Luo, N. Has Highway Construction Narrowed the Urban–Rural Income Gap? Evidence from Chinese Cities. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2020, 99, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Jiang, L. Urbanization forces driving rural urban income disparity: Evidence from metropolitan areas in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.W.; Liu, T.Y.; Chang, H.L.; Jiang, X.Z. Is urbanization narrowing the urban-rural income gap? A cross-regional study of China. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Bi, G. A multidimensional investigation on spatiotemporal characteristics and influencing factors of China’s urban-rural income gap (URIG) since the 21st century. Cities 2024, 148, 104920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Jin, B. Does the development of digital economy infrastructure reduce the urban-rural income gap? Theoretical experience and empirical data from China. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, L.; Williams, F. Remote rural home based businesses and digital inequalities: Understanding needs and expectations in a digitally underserved community. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 68, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Gao, Q.; Ju, K.; Ma, Y. How digital skills affect farmers’ agricultural entrepreneurship? An explanation from factor availability. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100477. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Q.; Wu, M.; Zhang, L. Endogenous growth and human capital accumulation in a data economy. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2023, 69, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Dan, T. Digital dividend or digital divide? Digital economy and urban-rural income inequality in China. Telecommun. Policy 2023, 47, 102616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, Y.; Si, H. Digital economy development and the urban–rural income gap: Intensifying or reducing. Land 2022, 11, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Cai, Z.; Wang, J. Digital village construction and Rural Household Entrepreneurship: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, G.; Arduini, S.; Uyar, H.; Psiroukis, V.; Kasimati, A.; Fountas, S. Economic and Environmental Benefits of Digital Agricultural Technologies in Crop Production: A review. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100441. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, F.; Yao, L.; Sun, Y.; Cai, Y. E-commerce participation, digital finance and farmers’ income. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2023, 15, 833–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zang, D.; Chandio, A.A.; Yang, D.; Jiang, Y. Farmers’ adoption of digital technology and agricultural entrepreneurial willingness: Evidence from China. Technol. Soc. 2024, 73, 102253. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L. Effect of digital inclusive finance on common prosperity and the underlying mechanisms. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 91, 102940. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, C.; Wang, J. How Can the Digital Economy Promote the Integration of Rural Industries—Taking China as an Example. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, L.J.; Townsend, L.; Roberts, E.; Beel, D. The rural digital economy. Scott. Geogr. J. 2015, 131, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zeng, Y.; Ye, Z.; Guo, H. E-commerce development and urban-rural income gap: Evidence from Zhejiang Province, China. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2021, 100, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Fan, J.; Li, W.; Xian, B.T.S. Can China’s digital inclusive finance help rural revitalization? A perspective based on rural economic development and income disparity. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 985620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L. Driving rural industry revitalization in the digital economy era: Exploring strategies and pathways in China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Liu, Q.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Khanal, R. How the Rural Digital Economy Drives Rural Industrial Revitalization—Case Study of China’s 30 Provinces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.Z.; Zeng, Y.T.; Lin, W.S. Do rural highways narrow Chinese farmers’ income gap among provinces? J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 905–914. [Google Scholar]

- Karine, H.A.J.I. E-commerce development in rural and remote areas of BRICS countries. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 979–997. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Min, S.; Ma, W.; Liu, T. The adoption and impact of E-commerce in rural China: Application of an endogenous switching regression model. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 83, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.H.; Choi, C.H. Does e-commerce narrow the urban–rural income gap? Evidence from Chinese provinces. Internet Res. 2022, 32, 1427–1452. [Google Scholar]

- Balog, M.; Demidova, S.; Lesnevskaya, N. Human capital in the digital economy as a factor of sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. Eng. Econ. 2022, 1, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmi, N. Financial inclusion and human capital investment in urban and rural: A case of Aceh Province. Reg. Sci. Inq. 2022, 12, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Salemink, K.; Strijker, D.; Bosworth, G. Rural development in the digital age: A systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 54, 360–371. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zhu, S.; Hou, Z.; Li, C. Digital village construction, human capital and the development of the rural older adult care service industry. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1190757. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.K.; Vu, T.V. Economic complexity, human capital and income inequality: A cross-country analysis. Jpn. Econ. Rev. 2020, 71, 695–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, C.; Huang, C. The Impact of digital village construction on County-Level Economic Growth and Its Driving Mechanisms: Evidence from China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, A.; Hou, Y.; Tan, J. How does digital village construction influences carbon emission? The case of China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278533. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. The core of China’s rural revitalization: Exerting the functions of rural area. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Wu, M.; Ma, L.; Wang, N. Rural finance, scale management and rural industrial integration. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2002, 12, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, L. Rural revitalization of China: A new framework, measurement and forecast. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 89, 101696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zang, Y.; Yang, Y. China’s rural revitalization and development: Theory, technology and management. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1923–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yang, X. Sustainable development levels and influence factors in rural China based on rural revitalization strategy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, H.; Jian, Y.; Shi, L. Multi-dimension evaluation of rural development degree and its uncertainties: A comparison analysis based on three different weighting assignment methods. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chai, Q.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, H. Construction and application of evaluation system for integrated development of agricultural industry in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 7469–7479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhao, P.; Hu, H.; Yan, J.; Chen, X. Exploring the heterogeneous impact of road infrastructure on rural residents’ income: Evidence from nationwide panel data in China. Transp. Policy 2023, 134, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Hu, Q. A re-examination of the influence of human capital on urban-rural income gap in China: College enrollment expansion, digital economy and spatial spillover. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 494–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Wei, H.; Lu, S.; Dai, Q.; Su, H. Assessment on the urbanization strategy in China: Achievements, challenges and reflections. Habitat Int. 2018, 71, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Turvey, C. Financial repression in China’s agricultural economy. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2009, 1, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charatsari, C.; Lioutas, E.D.; De Rosa, M.; Vecchio, Y. Technological innovation and agrifood systems resilience: The potential and perils of three different strategies. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 872706. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Index | Definition and Unit | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rural digital infrastructure | Internet popularity | Internet access per capita in countryside | Peng and Dan (2023) [26] |

| Fixed digital device popularity | Average year-end computer possession per 100 rural inhabitants | Zhao et al. (2023) [6] | |

| Mobile digital device popularity | Average year-end cell phone possession per 100 rural inhabitants | Zhao et al. (2023) [6]; Peng and Dan (2023) [26]; Hao et al. (2022) [49] | |

| Digitalization of rural industry | Sales digitization | Taobao village accounts for the proportion of administrative villages (%) | Hao et al. (2022) [49] |

| Digitalization of agricultural production | Share of administrative villages with Internet broadband service (%) | Hao et al. (2022) [49] | |

| Financial industry digitization | Digital finance digitization index | Chang (2022) [8]; Xiong et al. (2022) [36] | |

| Rural digital service | Digital financial services | Breadth of digital finance coverage index | Xiong et al. (2022) [36]; Hao et al. (2022) [49] |

| Mobile payment level | Mobile payment index | Xiong et al. (2022) [36] | |

| E-commerce service | Average number of rural deliveries per week | Hao et al. (2022) [49] |

| Dimension | Index | Definition and Unit | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural production capacity | Level of agricultural mechanization | Gross power of agricultural machinery/sown area of crops (kW/hm2) | Shi and Yang (2022) [54] Liu et al. (2021) [55] |

| Labor productivity | Gross output value of agriculture, forestry, livestock, and fisheries/sown area of crops (Million/hm2) | Liu et al. (2021) [55] | |

| Land productivity | Gross output value of agriculture, forestry, livestock, and fisheries/employment in primary industry (Million per person) | Liu et al. (2021) [55] | |

| Grain output | Total grain output/sown area of grain crops (t/hm2) | Luo et al. (2023) [37]; Tian et al. (2023) [38] | |

| Agricultural industry chain extension | Share of value added in primary sector | Value added in primary sector/GDP (%) | Luo et al. (2023) [37] |

| Percentage of output value of agro-processing industry | Main business income of agro-processing industry/gross output value of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fisheries (%) | Wang et al. (2021) [56] | |

| Rural cooperative situation | Number of rural farmers’ cooperatives/rural population | Wang et al. (2021) [56] | |

| Agricultural multifunctionality expansion | Leisure agriculture development | Leisure agriculture business income/gross agricultural output (%) | Wang et al. (2021) [56] |

| Facility agriculture development | Facility agricultural area/crop sown area (%) | Wang et al. (2021) [56] | |

| Percentage of agricultural services output | Output of agriculture, forestry, and fishery services/total (%) | Wang et al. (2021) [56] |

| Variables | Symbol | Definition and Unit | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban–rural income gap | Gap | Theil index | 0.091 | 0.040 |

| digital village construction | Digital | This value is calculated by the entropy method | 0.153 | 0.112 |

| Rural industry revitalization | RIR | This value is calculated on the basis of indicators | 0.227 | 0.084 |

| Urbanization rate | Urban | Urban permanent population/total population (%) | 0.581 | 0.131 |

| Industrial structure | Indus | Output value of tertiary industry/output value of secondary industry | 1.225 | 0.686 |

| Foreign trade of agricultural products | Trade | Total imports and exports of agricultural products/GDP (%) | 0.271 | 0.288 |

| Financial development | Fin | Loan balance of financial institutions/GDP (%) | 1.571 | 0.539 |

| Social security | Social | Social security and employment expenditure of local finance/general budget expenditure of local finance (%) | 0.130 | 0.034 |

| Transportation infrastructure development | Trans | Road and rail mileage/administrative area(km/km2) | 0.943 | 0.535 |

| Rural human capital | Rhc | Average years of schooling in the primary sector (years) | 7.544 | 0.871 |

| Type | Statistic | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kao test | Modified Dickey–Fuller t | 2.029 | 0.021 |

| Dickey–Fuller t | 3.386 | 0.000 | |

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −2.812 | 0.003 | |

| Unadjusted Modified Dickey–Fuller t | 1.396 | 0.081 | |

| Unadjusted Dickey–Fuller t | 2.724 | 0.003 | |

| Pedroni test | Modified Phillips–Perron t | 10.100 | 0.000 |

| Phillips–Perron t | −25.992 | 0.000 | |

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −20.047 | 0.000 | |

| Variables | lnGap | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| lnDigital | −0.217 *** | −0.094 *** | −0.025 *** | −0.046 *** |

| 0.028 | 0.014 | 0.007 | 0.010 | |

| lnUrban | N | −0.604 *** | −0.231 *** | −0.747 *** |

| 0.100 | 0.036 | 0.116 | ||

| lnIndus | N | −0.185 *** | −0.038 *** | −0.169 *** |

| 0.051 | 0.009 | 0.043 | ||

| lnTrade | N | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.015 |

| 0.0136 | 0.00558 | 0.01376 | ||

| lnFin | N | 0.138 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.113 *** |

| 0.036 | 0.009 | 0.029 | ||

| lnSocial | N | −0.107 * | 0.002 | −0.158 ** |

| 0.055 | 0.020 | 0.062 | ||

| Constant | −2.965 *** | −3.300 *** | 0.760 *** | −2.988 *** |

| 0.059 | 0.144 | 0.049 | 0.218 | |

| R-squared | 0.752 | 0.880 | 0.788 | 0.870 |

| Province fixed-effect | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hausman | 31.16 *** | - | - | |

| F value | 58.13 *** | 166.09 *** | 89.21 *** | 137.84 *** |

| Variables | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnGap | lnGap | lnRIR | lnGap | |

| lnDigital | −0.088 *** | −0.112 *** | 0.174 *** | −0.099 *** |

| 0.015 | 0.021 | 0.048 | 0.016 | |

| lnTrans | −0.175 ** | −0.271 *** | ||

| 0.085 | 0.078 | |||

| lnUrban | −0.481 *** | −0.446 *** | −0.35 | −0.682 *** |

| 0.115 | 0.129 | 0.216 | 0.115 | |

| lnIndus | −0.176 *** | −0.139 *** | 0.176 ** | −0.079 ** |

| 0.055 | 0.032 | 0.085 | 0.037 | |

| lnTrade | −0.003 | 0.011 | −0.017 | 0.021 |

| 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.032 | 0.017 | |

| lnFin | 0.133 *** | 0.093 *** | 0.054 | 0.074 ** |

| 0.035 | 0.024 | 0.096 | 0.029 | |

| lnSocial | −0.115 ** | −0.085 | 0.408 *** | −0.129 ** |

| 0.055 | 0.055 | 0.109 | 0.058 | |

| lnTrans*lnDigital | −0.029 *** | |||

| 0.006 | ||||

| lnRIR | −0.042 *** | |||

| 0.011 | ||||

| Cons | −3.317 *** | −3.211 *** | −0.612 ** | −3.365 *** |

| 0.137 | 0.146 | 0.305 | 0.165 | |

| N | 310 | 310 | 300 | 300 |

| adj. R2 | 0.881 | 0.895 | 0.373 | 0.897 |

| Soble test | - | - | 0.015 * | |

| 0.009 | ||||

| Bootstrap test | - | - | 0.015 * | |

| 0.009 |

| Threshold | RSS | MSE | Fstat | Prob | Crit10 | Crit5 | Crit1 | BS Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single | 0.564 | 0.002 | 24.680 | 0.020 | 17.415 | 20.729 | 27.332 | 300 |

| Double | 0.547 | 0.002 | 9.180 | 0.453 | 17.482 | 23.568 | 32.096 | 300 |

| Triple | 0.530 | 0.002 | 9.910 | 0.623 | 31.884 | 38.460 | 50.007 | 300 |

| Variables | lnGap | |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Standard Error | |

| lnUrban | −0.638 *** | 0.074 |

| lnIndus | −0.164 *** | 0.020 |

| lnTrade | −0.001 | 0.013 |

| lnFin | 0.152 *** | 0.022 |

| lnSocial | −0.100 *** | 0.030 |

| lnRhc ≤ 1.9954 | −0.083 *** | 0.013 |

| lnRhc > 1.9954 | −0.104 *** | 0.013 |

| Constant | −3.334 *** | 0.092 |

| adj. R2 | 0.874 | |

| N | 310 | |

| Variables | lnGap | lnGap | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| lnDigital | −0.120 *** | −0.0062 | −0.085 *** | −0.047 | −0.083 ** | −0.083 *** |

| 0.032 | 0.022 | 0.014 | 0.038 | 0.026 | 0.016 | |

| Constant | −3.235 *** | −4.0977 *** | −3.128 *** | −4.005 *** | −3.555 *** | −3.024 *** |

| 0.238 | 0.457 | 0.183 | 0.326 | 0.326 | 0.158 | |

| Control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| R-squared | 0.915 | 0.920 | 0.895 | 0.907 | 0.929 | 0.893 |

| F value | 266.05 *** | 5314.15 *** | 87.65 *** | 224.04 *** | 4147.52 *** | 70.25 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, M.; Liu, H. The Influence and Mechanism of Digital Village Construction on the Urban–Rural Income Gap under the Goal of Common Prosperity. Agriculture 2024, 14, 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14050775

Liu M, Liu H. The Influence and Mechanism of Digital Village Construction on the Urban–Rural Income Gap under the Goal of Common Prosperity. Agriculture. 2024; 14(5):775. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14050775

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Muziyun, and Hui Liu. 2024. "The Influence and Mechanism of Digital Village Construction on the Urban–Rural Income Gap under the Goal of Common Prosperity" Agriculture 14, no. 5: 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14050775

APA StyleLiu, M., & Liu, H. (2024). The Influence and Mechanism of Digital Village Construction on the Urban–Rural Income Gap under the Goal of Common Prosperity. Agriculture, 14(5), 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14050775