Identifying Credit Accessibility Mechanisms for Conservation Agriculture Farmers in Cambodia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

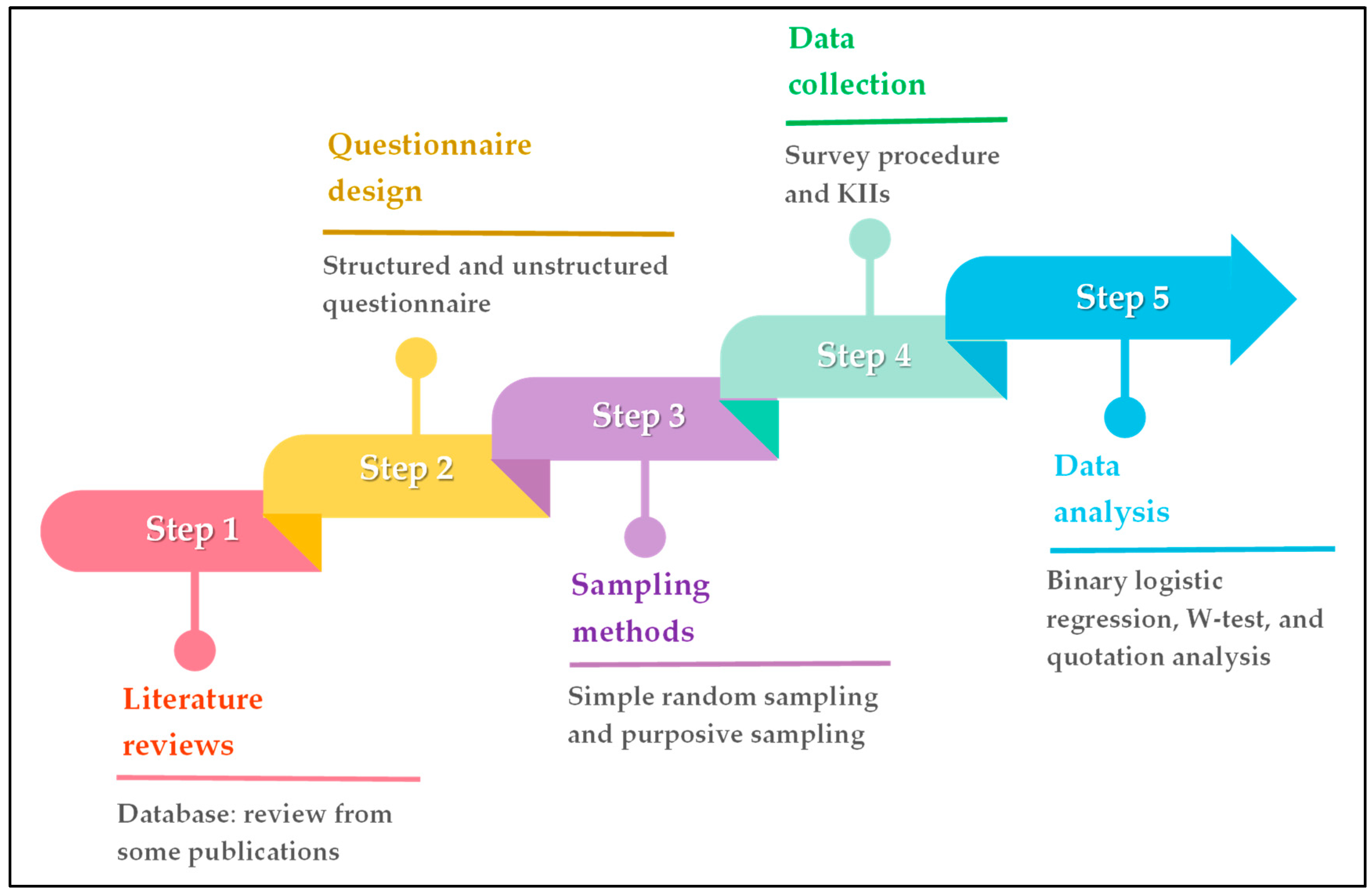

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Study Sites

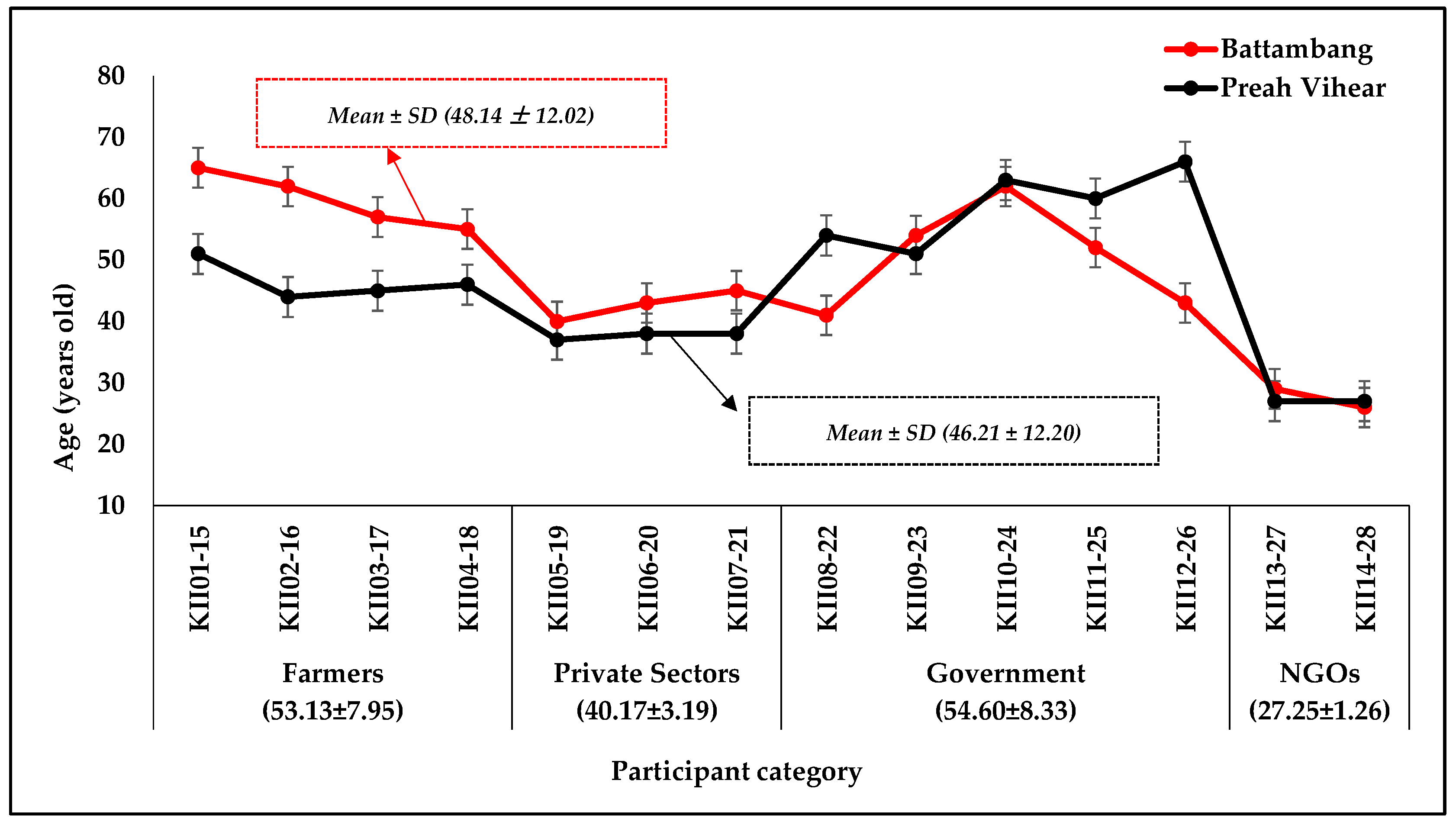

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Variables and Expectations

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Binary Logistic Regression Model

2.4.2. Kendall’s W-Test

2.4.3. Key Informant Interview

3. Results

3.1. Influencing Factors on Agricultural Credit Accessibility for CA Management Practices

3.2. The Ranking of Challenges to Access to Agricultural Credit for CA Management Practices

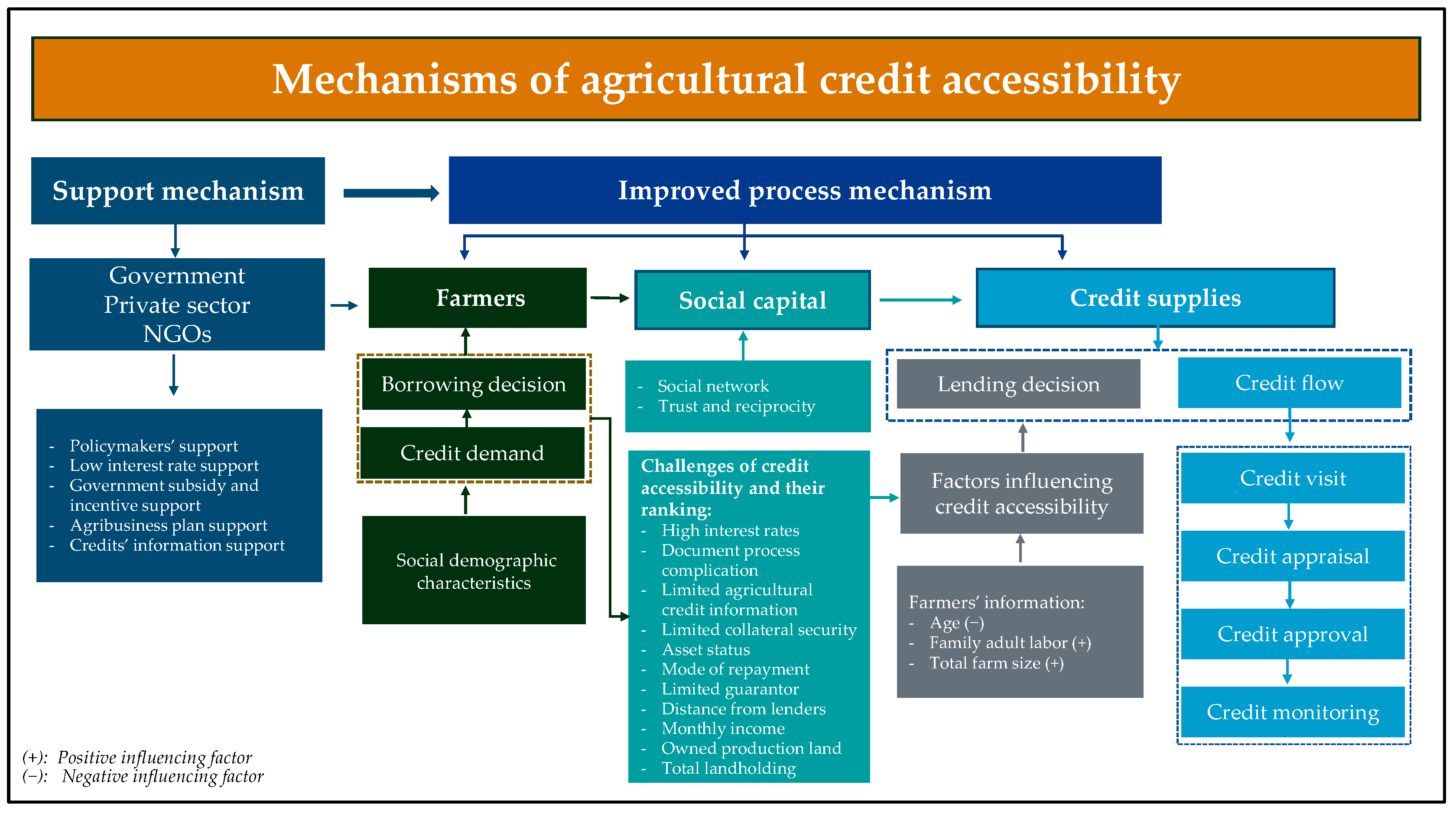

3.3. Mechanisms to Access Agricultural Credit for CA Management Practices

“The expected cost of CA inputs is a major issue for practicing CA in our community. The inputs include agricultural machinery, cover crops and land preparation. If we have access to credit, high interest rates are a challenge as well as credit information and document processes required by the FIs. We cannot access credit without credit information: interest rates, maximum and minimum loan amount and the document process. If we do not have the information, it will affect the process of documenting the FI’s requirements for accessing credit (Appendix A, Table A3)”.

“The primary obstacles to providing credit include business plans, farm size and monthly income. Limited farmers’ knowledge is an issue for credit accessibility. Most farmers cannot find information about agricultural credit by using Tonlesap app and the materials provided to promote CA is limited (Appendix A, Table A3) (KI07) (KI21)”.

“FIs should provide agricultural credit with lower interest rates to encourage farmers to access it, aiming to practice CA. The government and development programs of NGOs should provide subsidies for CA management practices, for example, land preparation and cover crops at 50%. This means that 50% would be subsidized by the government and NGOs while the remaining 50% would be paid by farmers (Appendix A, Table A3)”.“FIs would help provide agricultural credit to farmers who need them for CA management practices. Various actors including farmers, FIs and NGOs involved in project implementation should be engaged to address these issues. NGOs through their development programs should provide subsidies to all activities of farmers practicing CA, with 50% support allocated to farmers. Information support for business plans should be provided by NGOs. Policymakers should consider supporting farmers to improve agricultural credit by reducing the annual interest rates to lower than 17.6%. Government incentives, to give an example, and taxation support for agricultural input imports, should also be considered. This would impact the anticipated cost of CA inputs for agricultural machinery and cover crops (Appendix A, Table A3)”.

“To address issues, farmers should know how to create business plans, for instance, determining main crop types and required land size for crop production and estimating other expenses. Farmers should use agricultural credit for their intended purposes. In the business plan, they may allocate credit for agriculture (purchasing crop varieties), but afterward, farmers would divert it to another activity like buying a motorbike or phone. The solution provided by other financial officers included promoting CA through social media platforms like Facebook pages and YouTube. The Tonlesap app should be directly provided to farmers by FIs’ staff to support them to find donors for promoting CA through the app (Appendix A, Table A3)”.

“To build mechanisms to engage FIs to promote CA production systems, FIs should provide a low interest rate for agricultural credit and credit information should be broadly shared with farmers who need credit for agriculture related activities. Farmers should understand how to create business plans required by FIs for credit accessibility (Appendix A, Table A3) (KI01) (KI02)”.“Mechanisms for FIs to engage with CA management practices should include offering better credit terms in the agricultural sector such as lower interest rates compared to other types of credit. FIs should provide some documents and information support to farmers who need agricultural credit. The service providers should provide a better service and discounts to farmers who need their service. Incentives and subsidies from government and NGOs were valuable mechanisms to encourage FIs to work with farmers by providing information support. Policymakers should focus on agricultural credit accessibility with special interest rates (Appendix A, Table A3) (KI07) (KI21)”.“Mechanisms to engage FIs with farmers: the service providers should import tractors, which is a requirement for farmers who want to practice CA. FIs should provide better credit for agricultural activities as it would encourage farmers to practice CA. Special interest rates should be offered for agricultural credit. It is a mechanism by which farmers can access credit for agriculture and farmers themselves should have collateral assets and business plans for credit (Appendix A, Table A3) (KI23)”.“FIs should provide low interest rates for agricultural credit and follow up with farmers to ensure they are using the credit to achieve their goals or business plans. Information on agricultural credit should be provided directly to farmers via Telegram, phone call, App and training. Farmers who have small-scale operations should form groups to access services, namely, land preparation and agricultural credit (Appendix A, Table A3) (KI22)”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Influencing Agricultural Credit Accessibility for CA Management Practices

4.2. The Ranking of Challenges to Access Agricultural Credit for CA Management Practices

4.3. Mechanisms to Access Agricultural Credit for CA Management Practices

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Country | CA d | Research Method | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling | Quantitative | Qualitative | ||||

| 1 | Indonesia | No | Random | √ | - | [149] |

| 2 | Afghanistan | No | Random | √ | - | [150] |

| 3 | Nigeria | No | Random | √ | - | [151] |

| 4 | Vietnam | No | Random | √ | - | [142] |

| 5 | Nigeria | No | Random | √ | - | [47] |

| 6 | Vietnam | No | Random | √ | - | [54] |

| 7 | Ghana | No | Random | √ | - | [48] |

| 8 | Ghana | No | Random | √ | - | [32] |

| 9 | Africa | No | Random | √ | - | [152] |

| 10 | Ghana | No | Random | √ | - | [153] |

| 11 | Cambodia | Yes | Random and Purposive | √ | √ | This study |

| Model | AICc | Delta.AICc | AICcwt | AIC | Mallows’ Cp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 273.87 | 10.10 | 0.00 | 273.77 | 18.99 |

| Model 2 | 294.10 | 30.32 | 0.00 | 293.99 | 41.40 |

| Model 3 | 286.08 | 22.30 | 0.00 | 285.97 | 32.29 |

| Model 4 | 293.57 | 29.79 | 0.00 | 293.46 | 40.79 |

| Model 5 | 290.22 | 26.45 | 0.00 | 290.12 | 36.96 |

| Model 6 | 292.44 | 28.67 | 0.00 | 292.34 | 39.50 |

| Model 7 | 281.64 | 17.87 | 0.00 | 281.53 | 27.38 |

| Model 8 | 273.31 | 9.53 | 0.00 | 273.14 | 18.22 |

| Model 9 | 265.38 | 1.61 | 0.13 | 265.12 | 9.91 |

| Model 10 | 266.36 | 2.59 | 0.08 | 266.00 | 10.78 |

| Model 11 | 264.42 | 0.65 | 0.21 | 263.94 | 8.74 |

| Model 12 | 263.87 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 263.15 | 8.01 |

| Model 13 | 263.77 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 263.08 | 8.00 |

| Code | Position | Category | Province |

|---|---|---|---|

| KI 01 | CA farmer | Farmer | Preah Vihear |

| KI 02 | CA farmer | Farmer | Preah Vihear |

| KI 03 | Non-CA farmer | Farmer | Preah Vihear |

| KI 04 | Non-CA farmer | Farmer | Preah Vihear |

| KI 05 | Service provider | Private sector | Preah Vihear |

| KI 06 | Cover crop staff | Private sector | Preah Vihear |

| KI 07 | Financial institution | Private sector | Preah Vihear |

| KI 08 | PDAFF | Government | Preah Vihear |

| KI 09 | PDAFF | Government | Preah Vihear |

| KI 10 | Village chief | Government | Preah Vihear |

| KI 11 | Village chief | Government | Preah Vihear |

| KI 12 | Village chief | Government | Preah Vihear |

| KI 13 | CA implementer | NGO | Preah Vihear |

| KI 14 | CA implementer | NGO | Preah Vihear |

| KI 15 | CA farmer | Farmer | Battambang |

| KI 16 | CA farmer | Farmer | Battambang |

| KI 17 | Non-CA farmer | Farmer | Battambang |

| KI 18 | Non-CA farmer | Farmer | Battambang |

| KI 19 | Service provider | Private sector | Battambang |

| KI 20 | Cover crop staff | Private sector | Battambang |

| KI 21 | Financial institution | Private sector | Battambang |

| KI 22 | PDAFF | Government | Battambang |

| KI 23 | PDAFF | Government | Battambang |

| KI 24 | Village chief | Government | Battambang |

| KI 25 | Village chief | Government | Battambang |

| KI 26 | Village chief | Government | Battambang |

| KI 27 | CA implementer | NGO | Battambang |

| KI 28 | CA implementer | NGO | Battambang |

References

- Komarek, A.M.; Thierfelder, C.; Steward, P.R. Conservation agriculture improves adaptive capacity of cropping systems to climate stress in Malawi. Agric. Syst. 2021, 190, 103117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Conservation Agriculture. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/y4690e/y4690e0a.htm (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Shrestha, J.; Subedi, S.; Timsina, K.P.; Chaudhary, A.; Kandel, M.; Tripathi, S. Conservation agriculture as an approach towards sustainable crop production: A review. Farming Manag. 2020, 5, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Conservation Agriculture. Available online: https://www.fao.org/conservation-agriculture/en/ (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- The World Bank. Agricultural Land (% of Land Area)—Cambodia. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.AGRI.ZS?locations=KH (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- FAO; MAFF; CASIC. Bottom-Up Solutions to Promote Conservation Agriculture in Cambodia—Results from a Multistakeholder Policy Dialogue Process; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chinseu, E.; Dougill, A.; Stringer, L. Why do smallholder farmers dis-adopt conservation agriculture? Insights from Malawi. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierfelder, C.; Cheesman, S.; Rusinamhodzi, L. Benefits and challenges of crop rotations in maize-based conservation agriculture (CA) cropping systems of southern Africa. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2013, 11, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Sun, S. Fiscal incentives, financial support for agriculture, and urban-rural inequality. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 80, 102057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, A.; Sheikh, M.D.R.I.; Tushar, H.; Iqbal, M.M.; Far Abid Hossain, S.; Kamruzzaman, M. Does FinTech credit scale stimulate financial institutions to increase the proportion of agricultural loans? Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2114176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Oliver, A.J.; Irimia-Diéguez, A.I.; Vázquez-Cueto, M.J. Is there an optimal microcredit size to maximize the social and financial efficiencies of microfinance institutions? Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2023, 65, 101980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, D.A.; Adjei, P.O.-W.; Boafo, J. Microfinance, Rural Non-farm Activities and Welfare Linkages in Ghana: Assessing Beneficiaries’ Perspectives. Glob. Soc. Welf. 2017, 4, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidel, A.; Farrell, K.N. Small-scale cooperative banking and the production of capital: Reflecting on the role of institutional agreements in supporting rural livelihood in Kampot, Cambodia. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 119, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Le, T.D.Q. The interrelationships between bank profitability, bank stability and loan growth in Southeast Asia. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2084977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBC. Annual Report 2022; National Bank of Cambodia: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2023.

- Felkner, J.S.; Lee, H.; Shaikh, S.; Kolata, A.; Binford, M. The interrelated impacts of credit access, market access and forest proximity on livelihood strategies in Cambodia. World Dev. 2022, 155, 105795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Masetti, O.; Ren, J. Interest Rate Caps: The Theory and the Practice; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Villalba, R.; Venus, T.E.; Sauer, J. The ecosystem approach to agricultural value chain finance: A framework for rural credit. World Dev. 2023, 164, 106177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samreth, S.; Aiba, D.; Oeur, S.; Vat, V. Impact of the interest rate ceiling on credit cost, loan size, and informal credit in the microfinance sector: Evidence from a household survey in Cambodia. Empir. Econ. 2023, 65, 2627–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBC. Annual Supervision Report 2023; National Bank of Cambodia: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2024.

- NBC. Annual Supervision Report 2020; National Bank of Cambodia: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2021.

- The World Bank. Lending Interest Rate (%)—Thailand, Indonesia. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FR.INR.LEND?locations=TH-VN-LA-ID-MY (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Tram, H.T.X.; Nguyen, L.T.T. Interest rates and systemic risk:Evidence from the Vietnamese economy. J. Econ. Asymmetries 2023, 27, e00294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asni, F.; Mahamud, M.A.; Sulong, J. Management of Community Perception Issues to Ceiling and Floating Rates on Islamic Home Financing Based on Maqasid Shariah Concept. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, W.N.; Chhom, T.; Mony, R.; Estes, J. The Underside of Microfinance: Performance Indicators and Informal Debt in Cambodia. Dev. Change 2023, 54, 780–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylander, M. Credit as Coping: Rethinking Microcredit in the Cambodian Context. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2015, 43, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thath, R. Microfinance in Cambodia: Development, Challenges, and Prospects. Munich Pers. RePEc Arch. 2018, 89969, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Hartarska, V.; Zhang, L.; Nadolnyak, D. The Influence of Social Capital on Farm Household’s Borrowing Behavior in Rural China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehinde, A.D.; Adeyemo, R.; Ogundeji, A.A. Does social capital improve farm productivity and food security? Evidence from cocoa-based farming households in Southwestern Nigeria. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Nilsson, J.; Zhan, F.; Cheng, S. Social Capital in Cooperative Memberships and Farmers’ Access to Bank Credit–Evidence from Fujian, China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 418. [Google Scholar]

- Linh, T.N.; Long, H.T.; Chi, L.V.; Tam, L.T.; Lebailly, P. Access to Rural Credit Markets in Developing Countries, the Case of Vietnam: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongnaa, C.A.; Abudu, A.; Abdul-Rahaman, A.; Akey, E.A.; Prah, S. Input credit scheme, farm productivity and food security nexus among smallholder rice farmers: Evidence from North East Ghana. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2023, 83, 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, T.A.; Donkoh, S.A.; Ansah, I.G.K.; Awuni, J.A.; Cobbinah, M.T. Agricultural value chain participation and farmers’ access to credit in northern Ghana. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2023, 83, 800–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassouri, Y.; Kacou, K.Y.T. Does the structure of credit markets affect agricultural development in West African countries? Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 73, 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moahid, M.; Maharjan, K.L. Factors Affecting Farmers’ Access to Formal and Informal Credit: Evidence from Rural Afghanistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandio, A.A.; Jiang, Y. Determinants of Credit Constraints: Evidence from Sindh, Pakistan. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2018, 54, 3401–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, A.I.; Olayanju, T.; Ayeni, J.; Olaniru, O.S. Impact of bank credit on agricultural productivity: Empirical evidence from Nigeria (1981–2015). Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. (IJCIET) 2019, 10, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Onyiriuba, L.; Okoro, E.U.O.; Ibe, G.I. Strategic government policies on agricultural financing in African emerging markets. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2020, 80, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, E.; Kadanalı, E. The nexus between agricultural production and agricultural loans for banking sector groups in Turkey. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2022, 82, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, E.; Abid, M.; Zhang, L.; ul Haq, S.; Sahito, J.G.M. Agricultural advisory and financial services; farm level access, outreach and impact in a mixed cropping district of Punjab, Pakistan. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herliana, S.; Sutardi, A.; Aina, Q.; Himmatul Aliya, Q.; Lawiyah, N. The Constraints of Agricultural Credit and Government Policy Strategy. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 215, 02008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulume Bonnke, S.; Dontsop Nguezet, P.M.; Nyamugira Biringanine, A.; Jean-Jacques, M.S.; Manyong, V.; Bamba, Z. Farmers’ credit access in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Empirical evidence from youth tomato farmers in Ruzizi plain in South Kivu. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2071386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moahid, M.; Khan, G.D.; Yoshida, Y.; Maharjan, K.L.; Wafa, I.K. What farmers expect from the proposed formal agricultural credit policy: Evidence from a randomized conjoint experiment in Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2021, 81, 578–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Qiu, H.; Rahut, D.B. Rural development in the digital age: Does information and communication technology adoption contribute to credit access and income growth in rural China? Rev. Dev. Econ. 2023, 27, 1421–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekyi, S.; Abu, B.M.; Nkegbe, P.K. Effects of farm credit access on agricultural commercialization in Ghana: Empirical evidence from the northern Savannah ecological zone. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2020, 32, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, R.; Xia, L.C.; Ishaq, M.N.; Mukhtar, M.; Waseem, M. Determinants influencing the demand of microfinance in agriculture production and estimation of constraint factors: A case from south Region of Punjab Province, Pakistan. Int. J. Agric. Ext. Rural Dev. Stud. 2016, 3, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Balana, B.B.; Oyeyemi, M.A. Agricultural credit constraints in smallholder farming in developing countries: Evidence from Nigeria. World Dev. Sustain. 2022, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siaw, A.; Jiang, Y.; Ankrah Twumasi, M.; Agbenyo, W.; Ntim-Amo, G.; Osei Danquah, F.; Ankrah, E.K. The ripple effect of credit accessibility on the technical efficiency of maize farmers in Ghana. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2021, 81, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Tong, G.; Sikandar, F.; Erokhin, V.; Tong, Z. Financial Literacy and Credit Accessibility of Rice Farmers in Pakistan: Analysis for Central Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Regions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silong, A.K.F.; Gadanakis, Y. Credit sources, access and factors influencing credit demand among rural livestock farmers in Nigeria. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2020, 80, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wang, W.; Gan, C.; Cohen, D.A.; Nguyen, Q.T.T. Rural Credit Constraint and Informal Rural Credit Accessibility in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakshana, A.; Rajandran, K. Challenges and problems on farmers’ access to agricultural credit facilities in Cauvery Delta, Thanjavur District. St. Theresa J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mersha, D.; Ayenew, Z. Financing challenges of smallholder farmers: A study on members of agricultural cooperatives in Southwest Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 12, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Linh, T.N.; Anh Tuan, D.; Thu Trang, P.; Trung Lai, H.; Quynh Anh, D.; Viet Cuong, N.; Lebailly, P. Determinants of Farming Households’ Credit Accessibility in Rural Areas of Vietnam: A Case Study in Haiphong City, Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duniya, K.P.; Adinah, I.I. Probit Analysis of Cotton Farmers’ Accessibility to Credit in Northern Guinea Savannah of Nigeria. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2014, 4, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankrah Twumasi, M.; Jiang, Y.; Ntiamoah, E.B.; Akaba, S.; Darfor, K.N.; Boateng, L.K. Access to credit and farmland abandonment nexus: The case of rural Ghana. Nat. Resour. Forum 2022, 46, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, T.O.; Baiyegunhi, L.J.S. Determinants of credit constraints and its impact on the adoption of climate change adaptation strategies among rice farmers in South-West Nigeria. J. Econ. Struct. 2020, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, Y. Credit access and agricultural technology adoption nexus in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 10, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assouto, A.B.; Houngbeme, D.J.-L. Access to credit and agricultural productivity: Evidence from maize producers in Benin. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2023, 11, 2196856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Singh, P.K.; Mhaskar, M.D. Determinants of institutional agricultural credit access and its linkage with farmer satisfaction in India: A moderated-mediation analysis. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2023, 83, 211–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletschner, D.; Guirkinger, C.; Boucher, S. Risk, Credit Constraints and Financial Efficiency in Peruvian Agriculture. J. Dev. Stud. 2010, 46, 981–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.A.; Deininger, K.; Duponchel, M. Credit Constraints and Agricultural Productivity: Evidence from rural Rwanda. J. Dev. Stud. 2014, 50, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASIC. Conservation Agriculture and Sustainable Intensification (CA/SI) Farming in Cambodia; CASIC: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nickens, P.; Ader, D.R.; Miller, I.I.M.C.; Srean, P.; Gill, T.; Huot, S. Conservation agriculture and cover crop adoption by smallholder farmers in Cambodia: Understanding perceptions, challenges, and opportunities for soil improvement. Adv. Agric. Dev. 2023, 4, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omulo, G.; Birner, R.; Köller, K.; Simunji, S.; Daum, T. Comparison of mechanized conservation agriculture and conventional tillage in Zambia: A short-term agronomic and economic analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 221, 105414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. GDP per Capita (current US$)—Cambodia. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=KH (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- United Nations Cambodia. IFAD, the UN’s Rural Development Agency, and the Kingdom of Cambodia Deepen Partnership for Inclusive Agricultural Growth. Available online: https://cambodia.un.org/en/217977-ifad-un%E2%80%99s-rural-development-agency-and-kingdom-cambodia-deepen-partnership-inclusive (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- FAO. Cambodia Country Fact Sheet on Food and Agriculture Policy Trends; Food and Agriculture Policy Decision Analysis (FAPDA)—FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Heng, D.; Chea, S.; Heng, B. Impacts of Interest Rate Cap on Financial Inclusion in Cambodia; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sam, V. Formal Financial Inclusion in Cambodia: What are the Key Barriers and Determinants? MPRA paper 94000. 2019. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/94000/1/MPRA_paper_94000.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Sam, V. Formal credit usage and gender income gap: The case of farmers in Cambodia. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2021, 81, 675–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, V. Access to Formal Credit and Gender Income Gap: The Case of Farmers in Cambodia. MPRA paper 97052. 2019. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/97052/1/MPRA_paper_97052.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Phann, R.; Eang, D.; Srour, S.; Seng, D.; Pradhan, R. Metkasekor Handbook for Provincial Departments of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries; Swisscontact Cambodia: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lejissa, L.T.; Wakjira, F.S.; Tanga, A.A.; Etalemahu, T.Z. Smallholders’ Conservation Agriculture Adoption Decision in Arba Minch and Derashe Districts of Southwestern Ethiopia. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2023, 2023, 9418258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufa, A.H.; Kanyamuka, J.S.; Alene, A.; Ngoma, H.; Marenya, P.P.; Thierfelder, C.; Banda, H.; Chikoye, D. Analysis of adoption of conservation agriculture practices in southern Africa: Mixed-methods approach. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1151876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Krenzke, T.; Mohadjer, L. Considerations for selection and release of reserve samples for in-person surveys. Surv. Methodol. 2014, 40, 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, A.; Mahmood, N.; Zeb, A.; Kächele, H. Factors determining farmers’ access to and sources of credit: Evidence from the rain-fed zone of pakistan. Agriculture 2020, 10, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntshangase, N.L.; Muroyiwa, B.; Sibanda, M. Farmers’ Perceptions and Factors Influencing the Adoption of No-Till Conservation Agriculture by Small-Scale Farmers in Zashuke, KwaZulu-Natal Province. Sustainability 2018, 10, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, R. Conservation Agriculture for Africa: Building resilient farming systems in a changing climate. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 74, 1046–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, J.A.; González-Salazar, C. Akaike information criterion should not be a “test” of geographical prediction accuracy in ecological niche modelling. Ecol. Inform. 2019, 51, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azumah, S.B.; Donkoh, S.A.; Awuni, J.A. The perceived effectiveness of agricultural technology transfer methods: Evidence from rice farmers in Northern Ghana. Cogent Food Agric. 2018, 4, 1503798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnou, L.C.; Obossou, E.A.R.; Adjovi, N.R.A. Understanding the mechanisms of access and management of agricultural machinery in Benin. Sci. Afr. 2022, 15, e01121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhehibi, B.; Rudiger, U.; Moyo, H.P.; Dhraief, M.Z. Agricultural technology transfer preferences of smallholder farmers in Tunisia’s arid regions. Sustainbility 2020, 12, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshqaq, S.S.; Abuzaid, A.H.; Ahmadini, A.A. Selection of Optimal Regression-like Equations for Circular Regression Model via Mallows’ Cp and AIC Criteria. Iran. J. Sci. 2023, 47, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Cui, X.; Sun, J.; Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Ye, X.; Fan, B. Analysis of the distribution pattern of Chinese Ziziphus jujuba under climate change based on optimized biomod2 and MaxEnt models. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Xu, P.; Liu, X.; Xu, X. The impact of digital information treatment on the evaluation of service performance of agricultural extension agents. Inf. Dev. 2023, 0, 02666669231173003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARDB. Annual Report 2022; ARDB: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Widhiyanto, I.; Nuryartono, N.; Harianto, H.; Siregar, H. The Analysis of Farmers’ Financial Literacy and its’ Impact on Microcredit Accessibility with Interest Subsidy on Agricultural Sector. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2018, 8, 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Sebopetji, T.O.; Belete, A. An application of probit analysis to factors affecting small-scale farmers’ decision to take credit: A case study of the Greater Letaba Local Municipality in South Africa. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2009, 4, 718–723. [Google Scholar]

- Ukwuaba, I.C.; Owutuamor, Z.B.; Ogbu, C.C. Assessment of agricultural credit sources and accessibility in Nigeria. Rev. Agric. Appl. Econ. (RAAE) 2021, 23, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandio, A.A.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, F.; Rehman, A.; Liu, D. Famers’ access to credit: Does collateral matter or cash flow matter?—Evidence from Sindh, Pakistan. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2017, 5, 1369383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogubazghi, S.K.; Muturi, W. The effect of age and educational level of owner/managers on SMMEs’ access to bank loan in Eritrea: Evidence from Asmara City. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2014, 4, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanol, H.; Khemarin, K.; Elder, S. Labour Market Transitions of Young Women and Men in Cambodia; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Balogun, O.; Agumba, J.; Ansary, N. Evaluating credit accessibility predictors among small and medium contractors in the South African construction industry. Acta Structilia 2018, 25, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wang, W.; Gan, C.; Nguyen, Q.T.T. Credit Constraints on Farm Household Welfare in Rural China: Evidence from Fujian Province. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ma, W.; Mishra, A.K.; Gao, L. Access to credit and farmland rental market participation: Evidence from rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 63, 101523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, K.; Gebremedhin, B.; Zewdie, D.L. Factors affecting household decision to allocate credit for livestock production. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2017, 77, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mboulou, S.R. Determining the Magnitude of the Impact of Agricultural Credit on Productivity. J. Econ. 2020, 8, 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Saqib, S.E.; Kuwornu, J.K.M.; Ahmad, M.M.; Panezai, S. Subsistence farmers’ access to agricultural credit and its adequacy. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2018, 45, 644–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemessa, A.; Gemechu, A. Analysis of factors affecting smallholder farmers’ access to formal credit in Jibat District, West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia. Int. J. Afr. Asian Stud. 2016, 25, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Nasereldin, Y.A.; Chandio, A.A.; Osewe, M.; Abdullah, M.; Ji, Y. The credit accessibility and adoption of new agricultural inputs nexus: Assessing the role of financial institutions in Sudan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perveen, F.; Shang, J.; Zada, M.; Alam, Q.; Rauf, T. Identifying the determinants of access to agricultural credit in Southern Punjab of Pakistan. GeoJournal 2021, 86, 2767–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante-Addo, C.; Mockshell, J.; Zeller, M.; Siddig, K.; Egyir, I.S. Agricultural credit provision: What really determines farmers’ participation and credit rationing? Agric. Financ. Rev. 2017, 77, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, A.G.; Eusébio, G.d.S.; da Silveira, R.L.F. Can credit help small family farming? Evidence from Brazil. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2020, 80, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouman, M.; Siddiqi, M.; Asim, S.; Hussain, Z. Impact of socio-economic characteristics of farmers on access to agricultural credit. Sarhad J. Agric. 2013, 29, 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Saqib, S.E.; Kuwornu, J.K.M.; Panezia, S.; Ali, U. Factors determining subsistence farmers’ access to agricultural credit in flood-prone areas of Pakistan. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 39, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, D.; Christie, M.E.; Boulakia, S. Conservation agriculture and gendered livelihoods in Northwestern Cambodia: Decision-making, space and access. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awotide, B.A.; Abdoulaye, T.; Alene, A.; Manyong, V.M. Impact of Access to Credit on Agricultural Productivity: Evidence from Smallholder Cassava Farmers in Nigeria, AgEcon search; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MI, USA, 2015.

- Samreth, S.; Aiba, D.; Oeur, S.; Vat, V. Impacts of the Interest Rate Ceiling on Microfinance Sector in Cambodia: Evidence from a Household Survey; JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development: Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, 2021; pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Charoenseang, J.; Manakit, P. Thai monetary policy transmission in an inflation targeting era. J. Asian Econ. 2007, 18, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahathanaseth, I.; Tauer, L.W. Monetary policy transmission through the bank lending channel in Thailand. J. Asian Econ. 2019, 60, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBC. Annual Report 2017; National Bank of Cambodia: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2018.

- Mwonge, L.A.; Naho, A. Smallholder farmers’ perceptions towards agricultural credit in Tanzania. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 2022, 22, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandio, A.A.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, F.; Guangshun, X. Effects of agricultural credit on wheat productivity of small farms in Sindh, Pakistan. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2018, 78, 592–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.; Gupta, H. Sustainable women empowerment at the bottom of the pyramid through credit access. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2022, 42, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, J.I.F.; Bougard, D.A.; Jordaan, H.; Matthews, N. Factors Affecting Successful Agricultural Loan Applications: The Case of a South African Credit Provider. Agriculture 2019, 9, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundeji, A.A.; Donkor, E.; Motsoari, C.; Onakuse, S. Impact of access to credit on farm income: Policy implications for rural agricultural development in Lesotho. Agrekon 2018, 57, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awunyo-Vitor, D.; Mahama Al-Hassan, R.; Bruce Sarpong, D.; Egyir, I. Agricultural credit rationing in Ghana: What do formal lenders look for? Agric. Financ. Rev. 2014, 74, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assogba, P.N.; Kokoye, S.E.H.; Yegbemey, R.N.; Djenontin, J.A.; Tassou, Z.; Pardoe, J.; Yabi, J.A. Determinants of credit access by smallholder farmers in North-East Benin. J. Dev. Agric. Econ. 2017, 9, 210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Belay, M.; Bewket, W. Farmers’ livelihood assets and adoption of sustainable land management practices in north-western highlands of Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2013, 70, 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Honohan, P. Access to Financial Services. World Bank Res. Obs. 2009, 24, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambwa, D.; Mundike, J.; Chirambo, B. Enhancing sustainable mining with effective design of financial assurance programs: A viewpoint on the various legal and regulatory frameworks of Zambia, South Africa and Chile. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 8, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, R.; Glennon, D.; Nigro, P. Borrower–lender distance, credit scoring, and loan performance: Evidence from informational-opaque small business borrowers. J. Financ. Intermediation 2008, 17, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotugno, M.; Monferrà, S.; Sampagnaro, G. Relationship lending, hierarchical distance and credit tightening: Evidence from the financial crisis. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 1372–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfo, Y.; Musshoff, O.; Weber, R.; Danne, M. Farmers’ willingness to pay for digital and conventional credit: Insight from a discrete choice experiment in Madagascar. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalak, A.; Irani, A.; Chaaban, J.; Bashour, I.; Seyfert, K.; Smoot, K.; Abebe, G.K. Farmers’ Willingness to Adopt Conservation Agriculture: New Evidence from Lebanon. Environ. Manag. 2017, 60, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asogwa, B.; Abu, O.; Ochoche, G. Analysis of peasant farmers’ access to agricultural credit in Benue State, Nigeria. Br. J. Econ. Manag. Trade 2014, 4, 1525–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ijioma, J.C.; Osondu, C.K. Agricultural credit sources and determinants of credit acquisition by farmers in Idemili Local Government Area of Anambra State. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. B 2015, 5, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Teye, E.S.; Quarshie, P.T. Impact of agricultural finance on technology adoption, agricultural productivity and rural household economic wellbeing in Ghana: A case study of rice farmers in Shai-Osudoku District. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2022, 104, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulton, C.; Kydd, J.; Dorward, A. Overcoming Market Constraints on Pro-Poor Agricultural Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Dev. Policy Rev. 2006, 24, 243–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, S.; Hoy, S.; Thay, S.; Rimmer, M.A. Sustainable and inclusive development of finfish mariculture in Cambodia: Perceived barriers to engagement and expansion. Mar. Policy 2023, 148, 105439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafer, A.M.; Rikoon, J.S. Adoption of new technologies by smallholder farmers: The contributions of extension, research institutes, cooperatives, and access to cash for improving tef production in Ethiopia. Agric. Hum. Values 2018, 35, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, I.; Griffith, D.M.; Soriano, M.-A.; Murillo, J.M.; Madejón, E.; Gómez-Macpherson, H. What do farmers mean when they say they practice conservation agriculture? A comprehensive case study from southern Spain. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 213, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Thapa, G.B. Smallholders’ access to agricultural credit in Pakistan. Food Secur. 2012, 4, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huo, X. Impacts of land market policies on formal credit accessibility and agricultural net income: Evidence from China’s apple growers. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaleb, K.A.; Krupnik, T.J.; Erenstein, O. Factors associated with small-scale agricultural machinery adoption in Bangladesh: Census findings. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 46, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugoani, J.; Emenike, K.; Ben-Ikwunagum, D. Measuring farmers constraints in accessing bank credit through the agricultural credit guarantee scheme Fund in Nigeria. Am. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 1, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Van Auken, H.; Carraher, S. An Analysis of Funding Decisions for Niche Agricultural Products. J. Dev. Entrep. 2012, 17, 1250012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, B.; Kienzle, J. Mechanization of conservation agriculture for smallholders: Issues and options for sustainable intensification. Environments 2015, 2, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; Li, C. Human Capital, Social Capital, and Farmers’ Credit Availability in China: Based on the Analysis of the Ordered Probit and PSM Models. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, D.X.; Bauer, S. Does credit access affect household income homogeneously across different groups of credit recipients? Evidence from rural Vietnam. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buadi, D.K.; Anaman, K.A.; Kwarteng, J.A. Farmers’ perceptions of the quality of extension services provided by non-governmental organisations in two municipalities in the Central Region of Ghana. Agric. Syst. 2013, 120, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, W.N. Regulating Over-indebtedness: Local State Power in Cambodia’s Microfinance Market. Dev. Change 2020, 51, 1429–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovesen, J.; Trankell, I.-B. Symbiosis of Microcredit and Private Moneylending in Cambodia. Asia Pac. J. Anthropol. 2014, 15, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, W.N. From rice fields to financial assets: Valuing land for microfinance in Cambodia. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2019, 44, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, T. Building good management practices in Ethiopian agricultural cooperatives through regular financial audits. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2014, 2, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Agbo, F.; Ukwuaba, I.; Chiemela, C. The effects of interest rates on access to agro-credit by farmers in Kaduna State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 12, 3160–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harianto, H.; Hutagaol, M.P.; Widhiyanto, I. Sources and effects of credit accessibility on smallholder paddy farms performance: An empirical analysis of government subsidized credit program in Indonesia. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moahid, M.; Khan, G.D.; Yoshida, Y.; Joshi, N.P.; Maharjan, K.L. Agricultural Credit and Extension Services: Does Their Synergy Augment Farmers’ Economic Outcomes? Sustainability 2021, 13, 3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etonihu, K.; Rahman, S.; Usman, S. Determinants of access to agricultural credit among crop farmers in a farming community of Nasarawa State, Nigeria. J. Dev. Agric. Econ. 2013, 5, 192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Motsoari, C.; Cloete, P.C.; van Schalkwyk, H.D. An analysis of factors affecting access to credit in Lesotho’s smallholder agricultural sector. Dev. S. Afr. 2015, 32, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.-H.; Ayamga, M.; Awuni, J.A. Impact of agricultural credit on farm income under the Savanna and Transitional zones of Ghana. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2019, 79, 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Collection Methods | Provinces | Total (Household) | Access to Credit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BTB | PHV | Yes (%) | No (%) | ||

| Survey | 154 | 88 | 242 | 179 (74) | 63 (26) |

| KIIs | 14 | 14 | 28 | - | - |

| Total | 168 | 102 | 270 | 179 | 63 |

| Independent Variables | Unit of Measurement | With Access (n = 179) | Without Access (n = 63) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal (n = 160) a | Informal (n = 28) b | |||

| ± SD | ± SD | ± SD | ||

| Age | Householder age (years) | 47.28 ± 11.50 | 47.46 ± 11.16 | 55.40 ± 12.10 |

| Education | Education year (years) | 5.27 ± 3.29 | 4.53 ± 3.22 | 5.68 ± 3.86 |

| Family adult labor | Household members (num) | 3.25 ± 1.27 | 3.11 ± 1.62 | 2.70 ± 1.33 |

| Farm size for main crops | Only main crops (ha) | 4.75 ± 5.43 | 3.84 ± 3.00 | 5.02 ± 3.85 |

| Total farm size | Total farm size (ha) | 7.33 ± 7.98 | 4.86 ± 3.66 | 5.93 ± 7.28 |

| Farm experience | Number of years (years) | 21.93 ± 11.29 | 22.92 ± 13.27 | 28.50 ± 13.90 |

| On-farm income | Income per year (USD) | 7768.84 ± 13,085.72 | 6474.40 ± 7820.51 | 6845 ± 8186 |

| Variables | Coefficients | S.E. | Z Value | Pr (>z) | Odds | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.050 ** | 0.018 | −2.801 | 0.005 | 0.950 | 1.699 |

| Education year | −0.078 | 0.054 | −1.427 | 0.153 | 0.925 | 1.182 |

| Family adult labor | 0.353 ** | 0.135 | 2.620 | 0.008 | 1.424 | 1.035 |

| Farm size for main crops | −0.105 | 0.099 | −1.056 | 0.290 | 0.899 | 4.219 |

| Total farm size | 0.175 * | 0.081 | 2.137 | 0.032 | 1.189 | 3.900 |

| On-farm income | −0.000 | 0.000 | −1.092 | 0.274 | 0.999 | 1.259 |

| Farm experience | −0.021 | 0.016 | −1.288 | 0.197 | 0.979 | 1.629 |

| Constant | 3.151 ** | 0.999 | 3.154 | 0.001 | 23.359 | - |

| Items | Average Rank | SD | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

| High interest rates | 4.20 | 1.04 | 1 |

| Document process complication | 4.86 | 1.17 | 2 |

| Limited agricultural credit information | 5.41 | 1.17 | 3 |

| Limited collateral security | 6.09 | 1.27 | 4 |

| Asset status | 6.22 | 1.09 | 5 |

| Mode of repayment | 6.23 | 1.02 | 6 |

| Limited guarantor | 6.34 | 1.20 | 7 |

| Distance from lenders | 6.39 | 1.42 | 8 |

| Monthly income | 6.66 | 1.06 | 9 |

| Owned production land | 6.70 | 1.01 | 10 |

| Total landholding | 6.91 | 1.00 | 11 |

| n | 160 | ||

| Kendall’s W c | 0.09 ** | ||

| Chi-square | 151.49 | ||

| df | 10 | ||

| p value | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Men, P.; Hok, L.; Seeniang, P.; Middendorf, B.J.; Dokmaithes, R. Identifying Credit Accessibility Mechanisms for Conservation Agriculture Farmers in Cambodia. Agriculture 2024, 14, 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14060917

Men P, Hok L, Seeniang P, Middendorf BJ, Dokmaithes R. Identifying Credit Accessibility Mechanisms for Conservation Agriculture Farmers in Cambodia. Agriculture. 2024; 14(6):917. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14060917

Chicago/Turabian StyleMen, Punlork, Lyda Hok, Panchit Seeniang, B. Jan Middendorf, and Rapee Dokmaithes. 2024. "Identifying Credit Accessibility Mechanisms for Conservation Agriculture Farmers in Cambodia" Agriculture 14, no. 6: 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14060917