Abstract

This study investigates the perception of the implementation of the Farm to Table (F2T) concept on the sustainability of agritourism households in the Republic of Serbia. The main objective of the study is to determine how this concept affects the environmental, economic, and social sustainability of these households according to the participants. Data were collected through surveys of agritourism homestead owners in the regions of Vojvodina, Western Serbia, Southern Serbia, and Eastern Serbia. The research findings, obtained using quantitative (SEM) analyses, indicate that the F2T concept significantly contributes to the sustainable development of agritourism homesteads by increasing economic profitability, reducing environmental impact, and strengthening the social community. Moderators such as seasonal product availability, employee education, and the local community support have a significant impact on the effectiveness of F2T activities. The innovation of this study lies in the application of quantitative methods to analyze the specific impacts of the F2T concept on the sustainability of agritourism households, an area that has been poorly explored in the literature. The study has a number of implications, including providing empirical data that can help farmers, tourism operators, and policymakers to promote sustainable agritourism businesses.

1. Introduction

The farm to table (F2T) concept refers to the practice of directly connecting tourism businesses with local farms, thereby supporting the use of their own production in agritourism. The F2T concept includes short supply chains that allow food to go directly from the farm to the consumer’s table, often within agritourism homesteads. This concept differs from the Farm to Fork (F2F) concept, which can refer to a broader range of sustainable food chain initiatives, but both aim to promote local and sustainable agriculture [1,2]. The F2T concept can be implemented as a practical framework that various agritourism businesses and farms use to improve sustainability and the local food supply. This concept can be recognized as a theoretical notion but also as a concrete practice supported by various certification bodies. The certification bodies that oversee F2T initiatives are often local or national organizations dedicated to promoting sustainable agriculture and tourism, such as local tourism organizations, agricultural cooperatives, or independent certification bodies [3]. In the Republic of Serbia, many agritourism homesteads use the F2T concept to provide their guests with authentic local gastronomic experiences. This includes using fresh, seasonal products directly from their farm or from local producers. The certification of these practices is often carried out by local agricultural cooperatives and tourism organizations, which ensure that the products meet quality and sustainability standards. This concept includes ideas focused on using fresh, locally produced ingredients in providing tourism services, thereby reducing the time between harvest and consumption, improving food quality, and supporting the local economy [4,5]. The F2T concept also encompasses organizing activities that involve guests in the food production process and educating them about the importance of local food [6]. Some practices within the F2T concept may be mandatory, depending on specific certification and regulatory requirements. For example, there are standards that require a certain percentage of local ingredients in the offerings of households to qualify for certain certificates, such as the “Certificate of Food Justice” and other similar initiatives [4,7,8]. There is a certification system or point system that allows households to achieve F2T farm status, with certification conducted by organizations specialized in monitoring and auditing F2T practices [9,10,11,12]. Additionally, various forms of support are available, including financial assistance, training, and technical support for households that wish to adopt the F2T concept [13,14,15,16].

Ammirato and Felliceti [17] emphasize the importance of integrating economic, social, and ecological aspects in promoting sustainable rural tourism. Their research shows that the synergy of these elements can significantly contribute to the sustainable development of rural areas. This is supported by the research of Ciolac et al. [18], who found that agritourism, combined with this concept, enhances the health and environment of rural communities by integrating economic, social, and ecological components. Meanwhile, the same authors claim in their second piece of research that agritourism offers an alternative for farm diversification and supports the sustainability of rural mountainous areas [19]. It is important to note that locally produced agricultural products do not necessarily have to be completely organic. For example, the research by Barreiro-Hurle et al. [20] shows that the F2T strategy can significantly contribute to reducing the use of chemical pesticides and nutrient losses while increasing organic farming and reducing food waste, but it does not imply that all products must be organic.

In addition to the already mentioned benefits, the F2T concept also supports the principles of the circular economy. The circular economy, defined as a regenerative system that minimizes waste and emissions through the recycling and reuse of resources, is closely linked to the F2T strategy [21,22,23,24,25,26]. This strategy aims to reduce the environmental impact and promote sustainable practices in the food system [27,28]. By integrating food freshness with technological innovations, the F2T concept ensures that the food reaching consumers is as fresh and nutritionally valuable as possible [29]. Reducing the time between harvest and consumption allows products to retain more of their natural properties, which contributes to better nutrition and health for consumers. In this way, the F2T concept not only enhances the sustainability of the food supply chain but also directly improves the quality of life for end-users. The implementation of the F2T concept represents a significant step towards achieving the long-term sustainability of agritourism homesteads and the sustainable development of rural areas [30]. Accordingly, Felicetti et al. [31] emphasize the enormous importance of integrating this concept into rural development strategies to improve ecological sustainability. Based on this approach, the hypothesis is that the implementation of the F2T concept in agricultural households will contribute to the improvement of environmental sustainability:

H1:

The application of the F2T concept positively impacts the environmental sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

H1a:

Seasonal product availability (SPA) positively moderates the impact of the F2T concept on the environmental sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

H1b:

Employee education (EE) positively moderates the impact of the F2T concept on the environmental sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

H1c:

Technological infrastructure (TI) positively moderates the impact of the F2T concept on the environmental sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

H1d:

Local community support (LCS) positively moderates the impact of the F2T concept on the environmental sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

Agritourism homesteads that implement the F2T concept can reap economic benefits from more sustainable agricultural practices and have an increased attractiveness to tourists who value fresh, locally produced food [32]. Jin et al. [33] emphasize that the profitability of agritourism depends on factors such as the number of visitors, the number of employees, the duration of operations, and the business season. These findings suggest the need for the careful planning and management of agritourism facilities to maximize economic benefits. Furthermore, Escobar et al. [34] highlight the importance of adequate staffing for the success of agritourism initiatives. Their research indicates that quality training and the education of employees improve service and visitor experience, directly impacting the profitability and sustainability of these ventures. Similarly, Bagi and Reede [35] stated that public access to farms for recreation, proximity to central cities, and highly educated farmers all had a beneficial impact on agritourism involvement. Their research shows that these components contribute to the economic sustainability of farms through income diversification, enabling farmers to gain additional revenue sources and thus enhance their economic stability. Shortened supply chains, reduced costs, and improved product freshness within the F2T concept increase the food system’s resilience to external changes and enhance its sustainability [36]. This approach allows faster food distribution from producers to consumers, reducing storage and transportation time, resulting in fresher and higher-quality products. Reduced transportation and distribution costs also contribute to the system’s economic sustainability, while shortened supply chains reduce the environmental impact [37]. Ollenburg and Buckley [38] analyze the economic and social motivations of hosts in agritourism, emphasizing that the main motives for developing this tourism and the F2T concept are additional income and the preservation of rural communities. Farm tourism contributes to income diversification and the economic sustainability of agritourism homesteads, while social motivations include sharing the way of life and connecting with guests, thereby supporting the preservation of rural culture and traditions. Additionally, Smith et al. [39] found that organic systems associated with the F2T concept have 34% greater biodiversity and 50% higher profitability compared to conventional systems, despite 18% lower yields. According to their results, biodiversity increases with field size, suggesting that organic farming provides security in intensive environments. However, as the field size increases, the yield gap between organic and conventional farms grows, while the profitability advantages of organic farms diminish. An example of the importance of incorporating agritourism into rural area sustainability is illustrated by research conducted in Romania. In the mountainous regions of Romania, agritourism provides economic and social opportunities and contributes to the sustainability of rural communities through the synergy of local resources and tourist activities [40]. The following hypotheses were conceived based on the theoretical claims that the implementation of the F2T concept affects economic sustainability:

H2:

The application of the F2T concept positively impacts the economic sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

H2a:

Seasonal product availability (SPA) positively moderates the impact of the F2T concept on the economic sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

H2b:

Employee education (EE) positively moderates the impact of the F2T concept on the economic sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

H2c:

Technological infrastructure (TI) positively moderates the impact of the F2T concept on the economic sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

H2d:

Local community support (LCS) positively moderates the impact of the F2T concept on the economic sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

According to Moro-Visconti [41], the F2T concept leverages technology to enhance efficiency and social sustainability across all stages of the food system, from design and production to delivery and consumption. They further assert that digital platforms and innovative business models facilitate the tracking and authentication of food products throughout the supply chain, thereby enhancing transparency, safety, and reliability, all of which contribute to the social sustainability of communities. Additionally, Holland et al. [42] reveal that factors such as social media marketing, the use of smartphones in agricultural activities, and farm insurance significantly increase the likelihood of adopting agritourism, further strengthening the social sustainability of these homesteads. The perception of survival risk positively influences the adoption of agritourism as an enterprise to enhance social and economic sustainability through the tourism aspects of agriculture and rural landscapes [43,44,45,46].

A study conducted by Togaymurodov et al. [47] highlights the significant impact of education, technological advancement, and community support on the success and sustainability of agritourism in the Samarkand region of Uzbekistan. Innovative practices and active involvement of the local community are crucial for increasing economic potential and ensuring sustainable development. The implementation of the F2T principles further enhances these benefits by providing tourists with fresh, locally produced food, increasing the attractiveness of agritourism homesteads. As early as 2019, Whitt et al. [48] focused on the economic and social benefits of agritourism in the United States, concluding that farms engaged in agritourism achieve increased revenue, improved public education about agriculture, and the preservation of agricultural heritage. They also found that the proximity to urban areas and natural amenities significantly increases agritourism revenues. Integrating the F2T concept into these farms further enhances their economic performance and helps preserve local culinary traditions, reducing the environmental footprint by promoting local food [49,50,51,52]. Agritourism can prevent the migration of young people to cities, increase income through the sale of local products, and contribute to the economic vitality of rural communities [53,54].

H3:

The application of the F2T concept positively impacts the social sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

H3a:

Seasonal product availability (SPA) positively moderates the impact of the F2T concept on the social sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

H3b:

Employee education (EE) positively moderates the impact of the F2T concept on the social sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

H3c:

Technological infrastructure (TI) positively moderates the impact of the F2T concept on the social sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

H3d:

Local community support (LCS) positively moderates the impact of the F2T concept on the social sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

However, the application of F2T principles requires technological innovations and institutional support to ensure economic sustainability and achieve ecological and social goals [55,56]. Government support is crucial for the sustainability of organic food production, as direct payments enable farmers to adopt sustainable methods, reduce the environmental footprint, and encourage the production of healthy food [57,58]. This support is especially important for agritourism homesteads implementing F2T, as it allows for the adoption of sustainable methods and the offering of fresh, locally produced food, thereby increasing their attractiveness to tourists [59]. Research in Europe shows that direct payments play a key role in the sustainability of organic farms, and the importance of subsidies will grow with EU accession [60,61,62].

Nevertheless, there are also critical perspectives on the F2T concept [63,64]. Ammirato et al. [65] claim that agritourism can balance the needs of tourists and rural communities, providing economic and social development while mitigating negative ecological impacts. Efficient resource use, the preservation of cultural heritage, and the involvement of the local community are key factors for success. The integration of F2T activities enables more efficient resource use and reduces the environmental footprint, contributing to the overall sustainability of rural areas. However, the same authors warn of significant challenges and concerns regarding the implementation of F2T. Key challenges include cultural conflicts and bureaucratic obstacles that can hinder the implementation of agritourism. There is a fear that insufficient institutional support and regulation could jeopardize the long-term sustainability of these initiatives, causing negative ecological and social consequences [66].

Wesseler [67] points out that the implementation of the F2T strategy will lead to a reduction in agricultural production within the EU and an increase in food prices, which will negatively impact consumers. Although farmers’ incomes are expected to rise, the overall effects on welfare will be negative. The reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and the improvement of biodiversity are partially quantified, but their ability to offset economic losses remains uncertain. The same author also asserts that additional technological and institutional changes, such as the enhanced application of modern biotechnology, will be necessary to achieve the strategy’s goals and ensure long-term sustainability.

Based on an analysis of the existing literature and recognized trends, this study investigates the impact of implementing the F2T concept on specific aspects of sustainability of agritourism homesteads in the Republic of Serbia. The main goal of the study is to explore the targeted contributions of this concept to the ecological and economic sustainability of these households, with a special focus on the most relevant and manageable factors. This research focuses on participants’ perceptions of the impact of the “farm to table” (F2T) concept on the sustainability of agritourism homesteads. We do not directly measure the actual impacts on ecological, economic, or social aspects; instead, we analyze the attitudes and opinions of participants regarding the potential benefits of the F2T concept. Besides the main objective, the research also analyzes the moderators that can affect the effectiveness of the F2T concept application. Seasonal product availability, employee education, technological infrastructure, and local community support have been identified as key moderators. Sustainable development is a complex and multidimensional concept that requires an integrative approach to understand all aspects contributing to overall sustainability. Researching the ecological, economic, and social dimensions together allows for a comprehensive view of the impact of the F2T concept on agritourism homesteads. Through this approach, we can identify synergistic effects and interdependencies between different aspects of sustainability, enabling a deeper understanding and more effective implementation of sustainable practices.

Existing research gaps include insufficiently explored economic, environmental, and social effects of the F2T concept on agritourism homesteads, as well as a lack of quantitative data linking F2T to sustainable rural development. These gaps represent a key reason and motivation for conducting this research.

The innovation of this study lies in its comprehensive approach that uses quantitative methods to analyze in detail the impact of the farm to fork (F2T) concept on the sustainability of agritourism homesteads. The study provides empirical data on how the application of the F2T concept can increase the profitability of agritourism homesteads by reducing transport costs and increasing attractiveness for tourists. It highlights the ways in which F2T contributes to reducing the ecological footprint and promoting sustainable agricultural practices, while linking F2T to the preservation of local culture and traditions, as well as improving the quality of life in rural communities. A particularly innovative aspect of this study is its focus on the synergistic effect of the F2T concept that integrates food freshness with technological innovation. This enables the faster distribution of food from producer to consumer, reducing storage and transportation time, and ultimately resulting in fresher and better quality products. In this way, the study not only contributes to theoretical knowledge about sustainability, but also provides practical guidelines for improving the economic, environmental, and social sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

2. Methodology

We selected Clarivate Analytics Web of Science as one of the most comprehensive database and citation indexing services in order to obtain an overview of global research results in our reference domain. The sample comprised articles published in the last decade (between 2014 and 2024) (Figure 1), as our interest was in mapping current research trends on this topic. Only those articles that contained terms “agritourism” OR “rural tourism” OR “farm tourism” in title, abstract, and/or keywords were selected, following the precedent set by Rauniyar et al. [68] in a previous work. Our sample included only journal articles, as they typically contain the latest research findings and empirical data, and our manuscript is not exclusively bibliometric [69]. For several reasons, other types of publications were not included. Editorial materials are diverse and infrequently published, making precise bibliometric analysis difficult. Additionally, meeting abstracts and conference papers have less scientific impact and often lack references, complicating citation analysis. Book chapters and reviews usually summarize previous findings, whereas we are interested in current trends. Papers from the so-called “gray zone” or non-indexed papers were excluded because they are not present in scientific databases and cannot be included in the analysis [70]. Although we are aware that there is a possibility of including inferior works in this database, Web of Science was chosen for its comprehensiveness and accessibility. Limited access to other databases presents a challenge, but we believe that Web of Science provides a sufficiently comprehensive overview of research in our reference field.

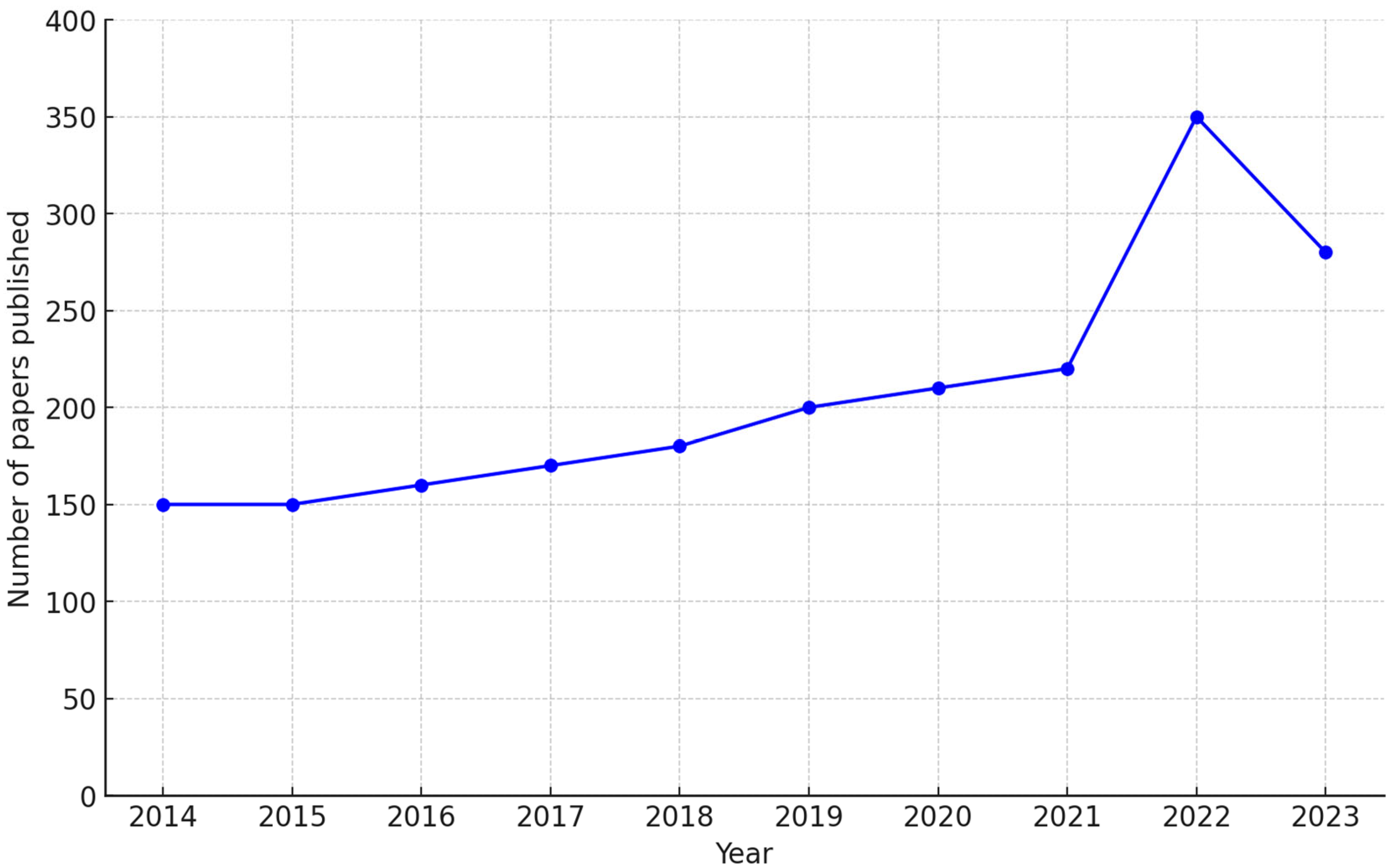

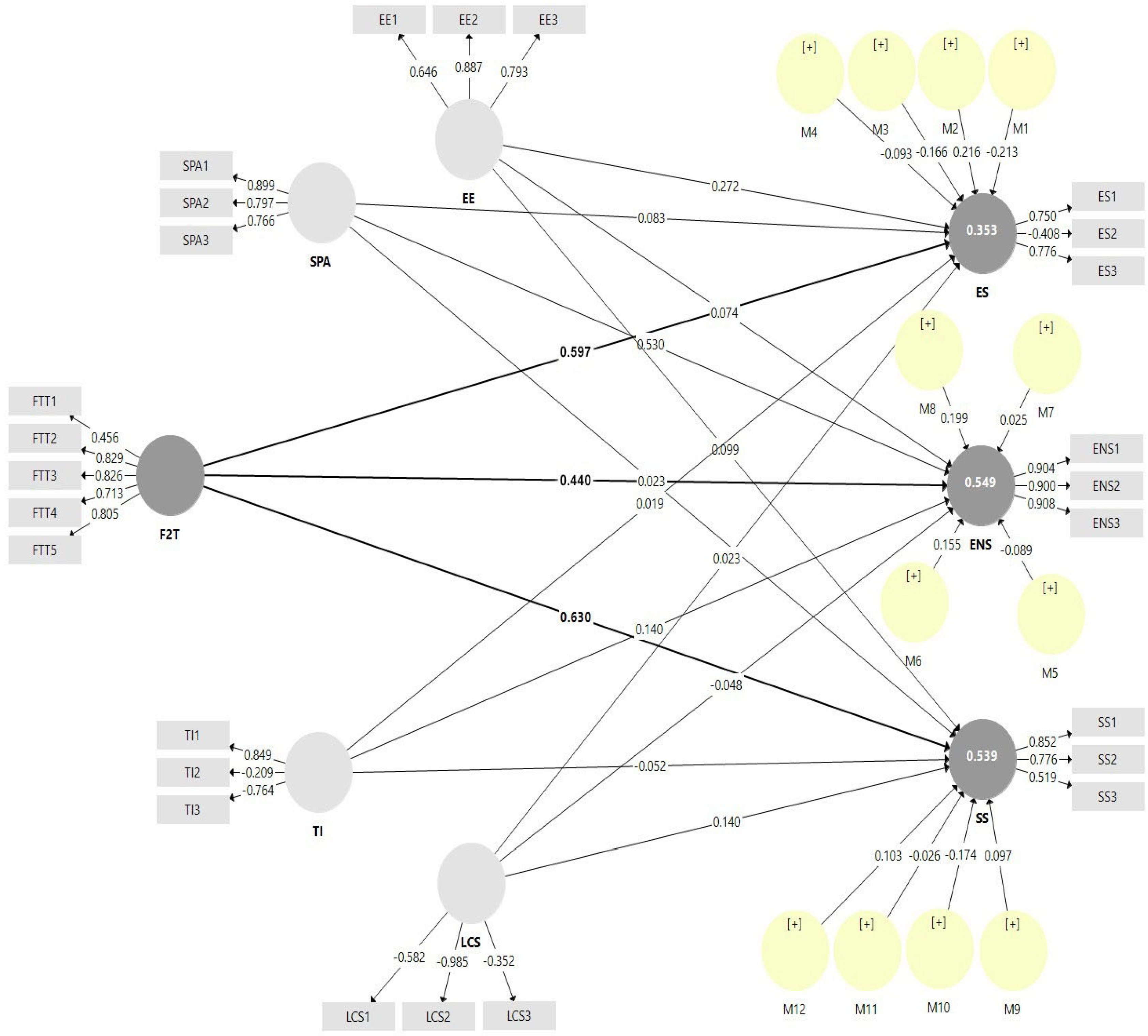

Figure 1.

Frequencies of published papers per year in the last decade.

A total of 2082 articles published in 554 journals were retrieved. In addition, we looked for the 5 most-cited documents in our sample (Table 1). Initially, we mapped the frequency of published papers per year, focusing on the last decade. As can be seen in Figure 1, there is a noticeable growing interest towards research on agritourism.

Table 1.

The most-cited articles.

Focusing on the country of origin, the results showed that most of the published papers come from People’s Republic of China (467 or 22.43%) followed by Spain (244 or 11.72%), USA (179 or 8.60%), and Italy (139 or 6.68%).

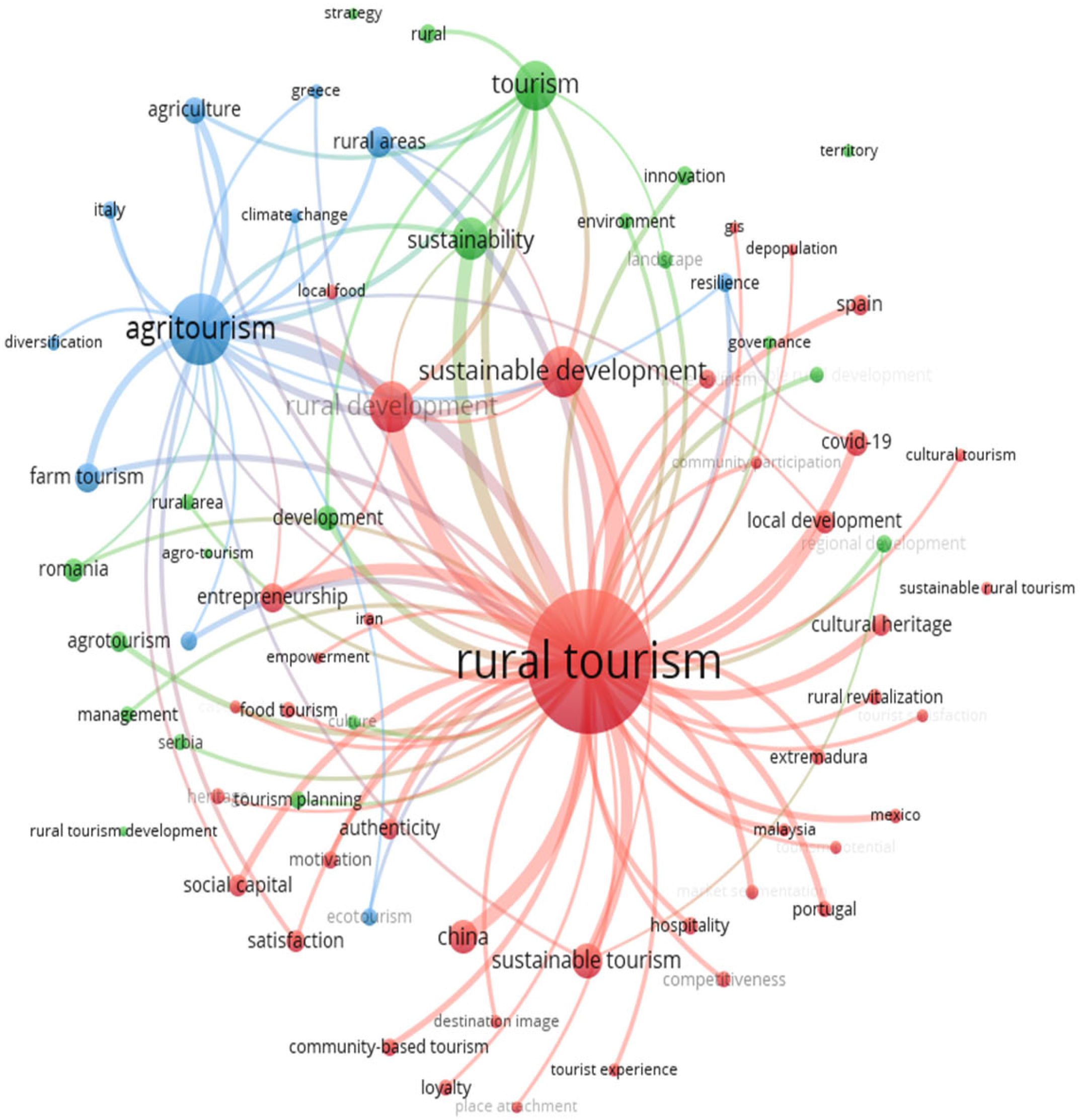

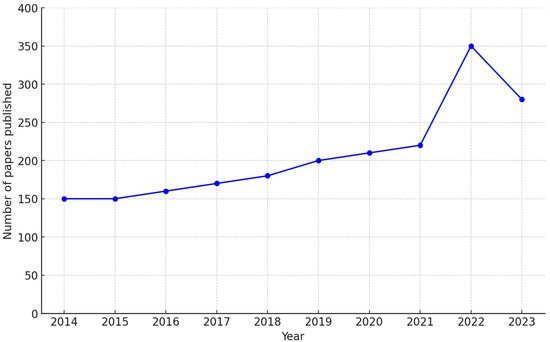

In order to obtain an insight into the main research subjects in the field of agritourism, we applied the co-occurrence of keyword analysis. In this type of map, circles represent the bibliographic items, while the lines represent the strength of the link between them. The different clusters that the items belong to are represented by different colors.

Our results revealed three different clusters (Figure 2). The first and the largest cluster gathers mostly general terms such as rural tourism, sustainable development, rural development, etc. In the second cluster, the central terms are sustainability and tourism, while the last and the smallest one contains terms related to agritourism, agriculture, and farm tourism.

Figure 2.

Co-occurrence of keywords map (network visualization).

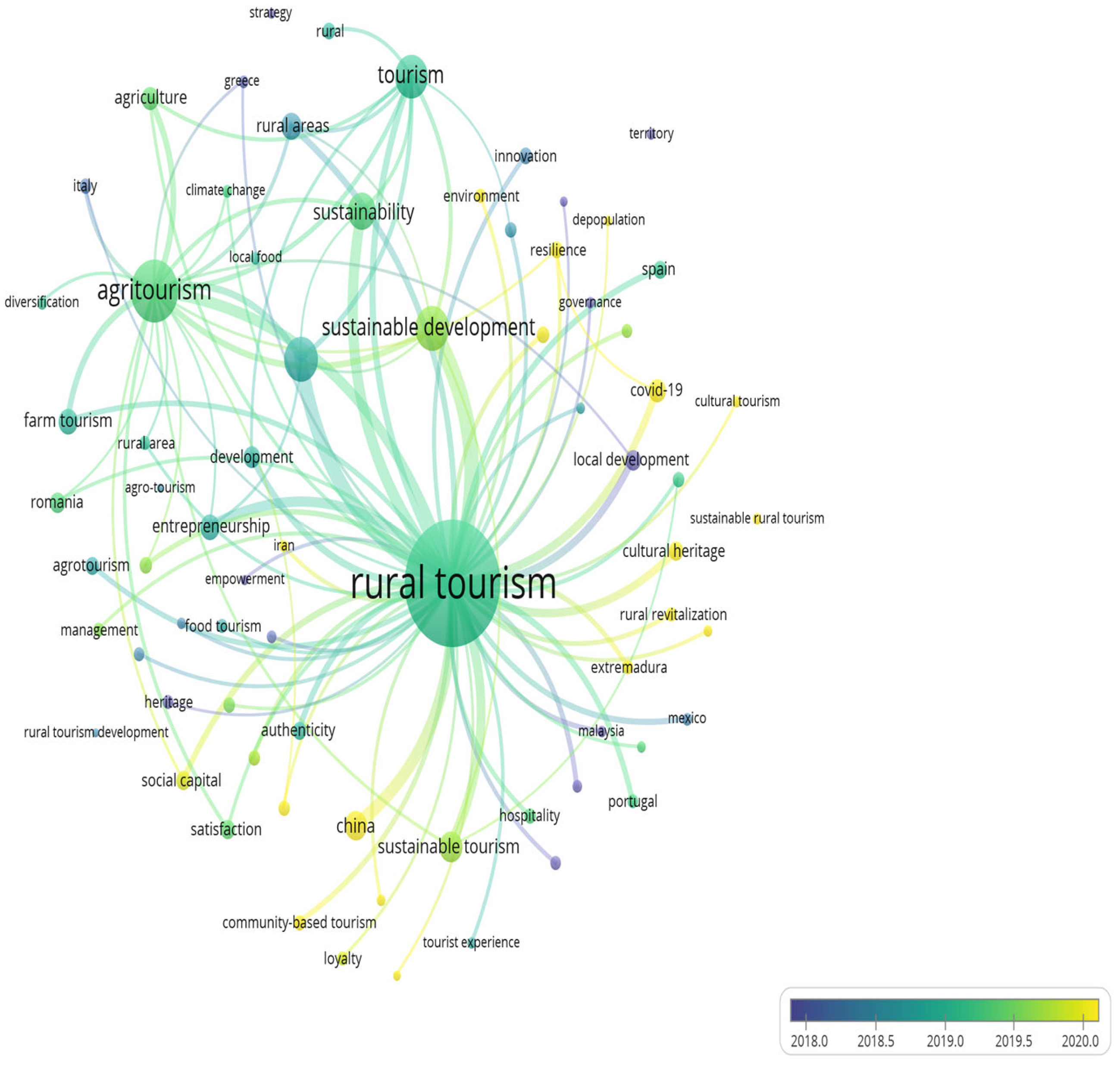

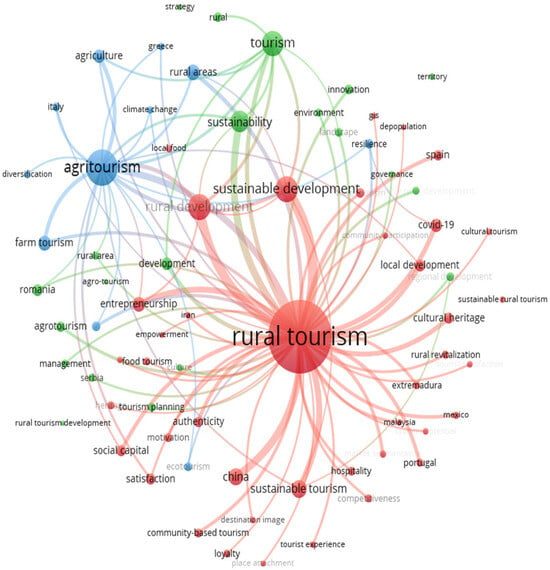

Moreover, when the overlay visualization method was applied (Figure 3), the results showed that the keywords from the first cluster also belong to the latest publications.

Figure 3.

Co-occurrence of keywords map (overlay visualization).

By applying these two analyses, we mapped the core research subjects in the field of agritourism in general, but also the “hottest topics” that the latest publication frequently dealt with.

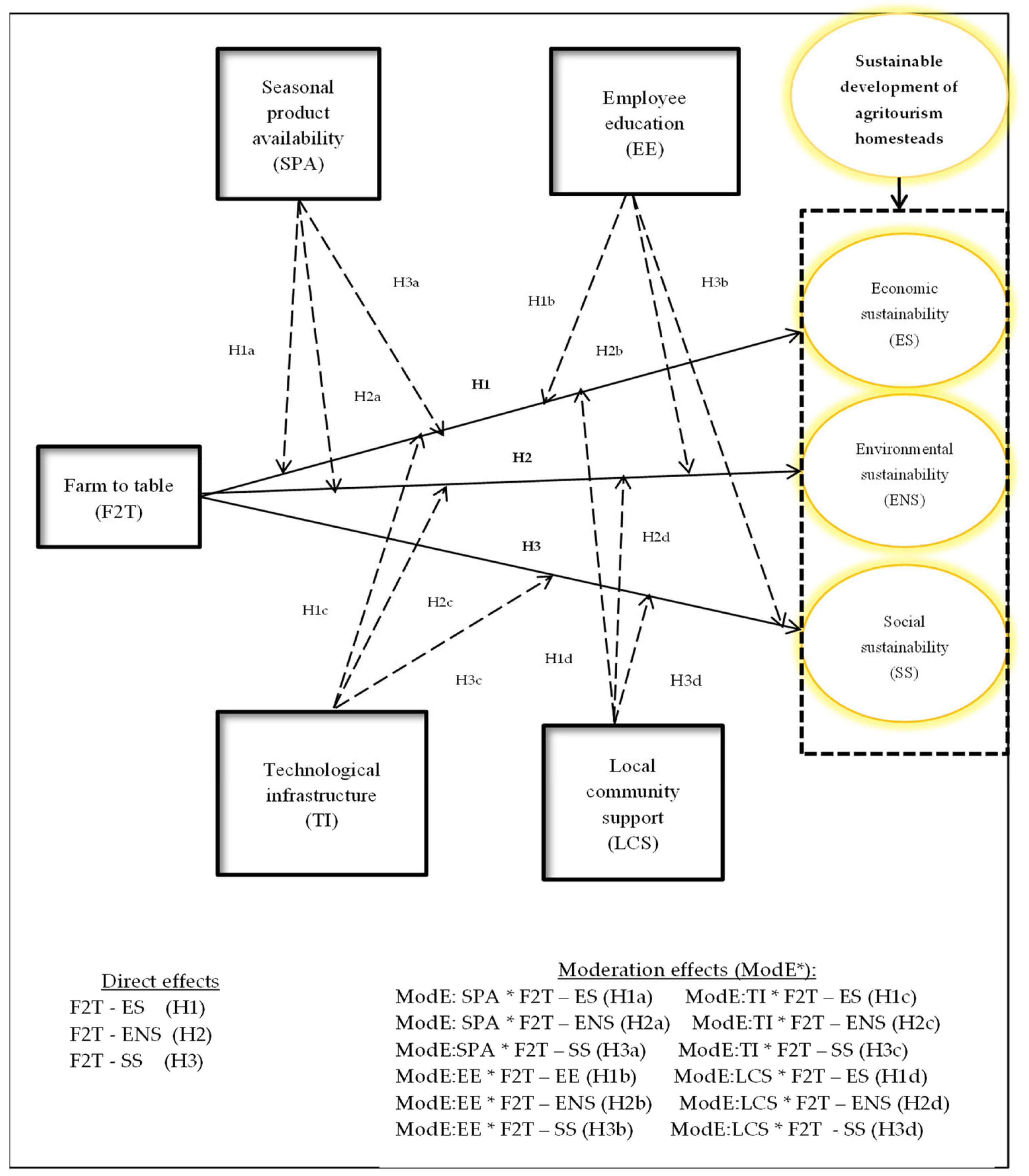

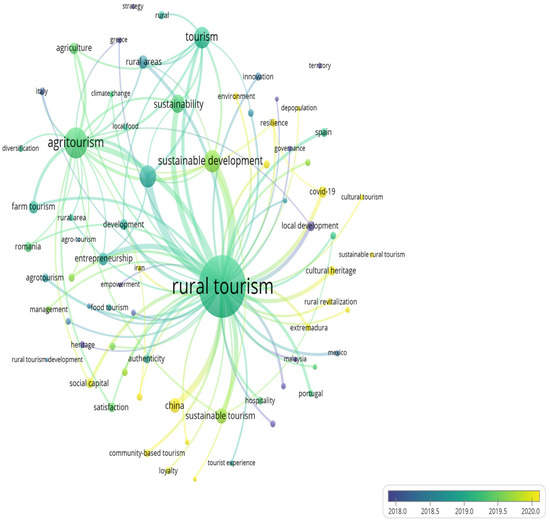

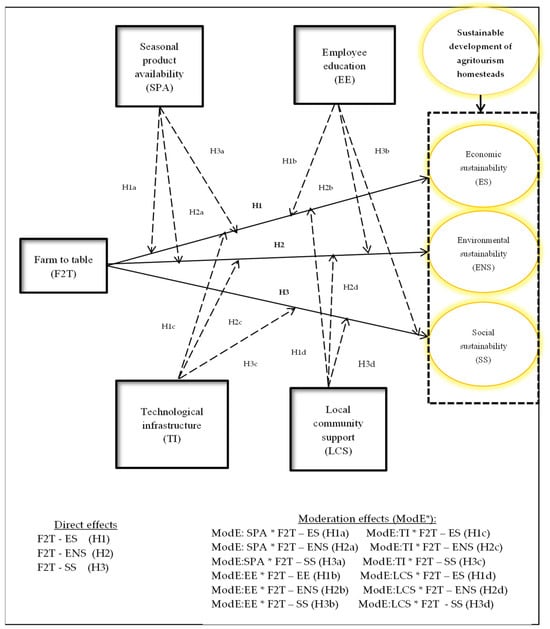

We developed a model for this research that examines the economic, ecological, and social aspects of applying the F2T concept in agritourism homesteads, with the aim of identifying key factors that contribute to their sustainability (Figure 4). The model was developed based on an extensive review of the relevant literature. The model integrates findings from various studies that examine the economic, ecological, and social impacts of the F2T concept on agritourism homesteads. Key references that informed the development of this model include studies by Raso et al. [17] on the sustainability of agritourism, Ciolac et al. [18,19] on the integration of economic, social, and ecological components in rural tourism, and Barreiro-Hurle et al. [20] on the environmental impacts of sustainable agricultural practices. Additionally, the model incorporates insights from research by Jin et al. [33] and Escobar et al. [34] on the economic viability of agritourism operations, as well as studies by Patra et al. [76] and Abdalla et al. [77] on the role of consumer education and technological innovations in promoting sustainable agricultural practices.

Figure 4.

Proposed research model.

2.1. Sample and Procedure

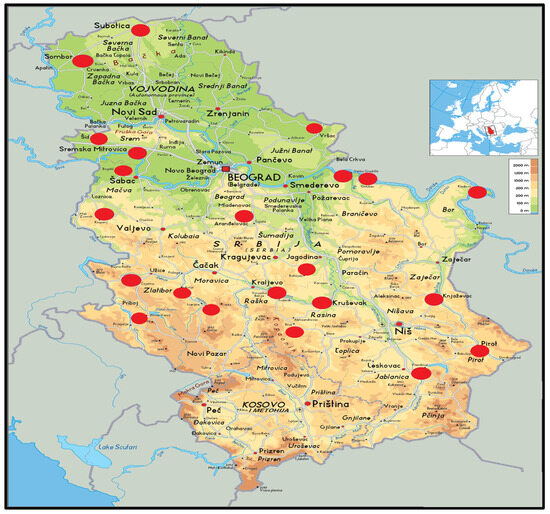

We selected 146 agritourism homesteads using a multi-stage sampling procedure to ensure representativeness and geographical diversity. The first phase involved identifying all agritourism homesteads that provide accommodation and food services in the Republic of Serbia, totaling 300 agritourism homesteads. This number was confirmed through regional tourism organizations and relevant databases. In the second phase, we divided the population into four geographical regions: Vojvodina, Western Serbia, Southern Serbia, and Eastern Serbia. This stratification was performed to ensure that the sample reflects the geographical diversity of agritourism homesteads across the country (Figure 5). In the final phase, we used a stratified random sampling technique within each region. Households were randomly selected from each stratum, ensuring that each homestead had an equal chance of being included in the sample.

Figure 5.

Map of research areas in the Republic of Serbia. Note: red circles—the location of the research municipalities.

This approach resulted in the selection of 146 agritourism homesteads, which represents 48.67% of the total number of agritourism homesteads in Serbia. This percentage was chosen to achieve sufficient statistical power for the analysis and to ensure the representativeness of the data. Table 2 shows the geographical distribution of the sample of agritourism homesteads by region.

Table 2.

Geographic distribution of the sample.

In the research, we included the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents in order to obtain a more comprehensive insight into the factors that influence the sustainability of agritourism homesteads and the implementation of the F2T concept. The sociodemographic characteristics we examined included age, gender, level of education, length of experience in agritourism, homestead size, and employment (whether the household is the only occupation or if they have additional jobs). Table 3 shows the detailed sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic characteristics of owners of agritourism homesteads.

Questionnaires were distributed via personal delivery to ensure a higher response rate and data accuracy. In this research, we used a survey to collect data on participants’ perceptions regarding the impact of the F2T concept on sustainability. The questions are designed so that respondents express their opinion on whether the F2T concept improves soil quality, reduces pollution and the ecological footprint, increases economic benefits, and contributes to social sustainability. Responses were collected over a three-month period, from December 2023 to March 2024. The questionnaire contained structured questions with a five-point Likert scale, allowing respondents to rate their level of agreement with statements from “1” (strongly disagree) to “5” (strongly agree). This methodology enabled the collection of detailed and relevant data on various aspects of the sustainability of agritourism homesteads. The education variables were treated as interval variables rather than categorical ones because they were assessed based on the respondents’ attitudes toward education related to the implementation of the F2T concept, rather than their actual level of education. These attitudes were measured using a Likert scale, which allows for a range of responses to capture the degree of agreement or disagreement with specific statements. This approach provides an important understanding of how respondents perceive the importance of education in the context of F2T concept, as opposed to simply categorizing their educational background.

2.2. Questionnaire Design

The statements for assessing the sustainability of agritourism homesteads were developed based on the research by authors Musa and Chin [78], which provided key insights into the economic, social, and ecological dimensions of sustainability in F2T activities in agritourism. Additionally, further literature was used to identify and formulate the moderators that affect the sustainability of these homesteads. The main independent variable in this study is the F2T concept, which was measured based on the respondents’ perceptions of various aspects of F2T practices. For example, the respondents evaluated statements such as “The F2T concept increases the attractiveness and recognition of homesteads” or “F2T initiatives offer unique gastronomic experiences”. These statements measure respondents’ subjective perceptions of the impact of the F2T concept rather than the actual implementation practices. It is important to note that all responses are based on respondents’ perceptions and do not reflect any actual measurements, such as the percentage of locally sourced or produced foodstuffs. Perception-based responses can carry a risk of moral hazard if the researcher fails to avoid asking leading questions. However, we addressed this problem by using unobtrusive measures. Unobtrusive measures include carefully formulating questions to reduce the pressure on respondents to give socially desirable answers and to ensure that their responses are as honest and accurate as possible. For example, instead of directly asking respondents, “Does the F2T concept increase the attractiveness and recognition of households?”, we asked, “To what extent do you agree with the statement that the F2T concept increases the attractiveness and recognition of your household?”. This approach allows respondents to answer more naturally, reducing the pressure to give socially desirable responses. Additionally, we used multiple data sources to triangulate the results and confirm their accuracy.

The questionnaire contained structured statements related to various aspects of the sustainability of agritourism homesteads and the implementation of the F2T concept. The statements were grouped into the following categories: social sustainability (SS) (3 statements), economic sustainability (ES) (3 statements), environmental sustainability (ENS) (3 statements), F2T (5 statements), seasonal product availability (SPA) (3 statements), employee education (EE) (3 statements), technological infrastructure (TI) (3 statements), and local community support (LCS) (3 statements). The same table shows a high reliability and validity for all analyzed factors. Social, economic, and ecological sustainability, as well as the F2T concept, demonstrate consistency in measurement and positive impacts on various aspects of sustainability. Seasonal product availability, employee education, technological infrastructure, and local community support further confirm their roles in the sustainability of agritourism homesteads. Additionally, some authors argue that for each variable designated as a “moderator”, at least eight statements should be used to achieve a greater reliability and validity of the measures. Using only a few statements to measure these variables may be insufficient and could affect the accuracy of the research results. However, there are examples in the literature where authors have used fewer than eight statements for moderation. For instance, Fairchild et al. [79] and Edwards and Stone-Romero [80] demonstrated that it is possible to use a smaller number of statements for certain moderators in their studies, which yielded satisfactory results.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 23.0, applying descriptive statistical analysis, mean (m), standard deviation (sd), Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), KMO test, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity [81]. Factor analysis was then conducted to determine the data structure [82]. The KMO measure of the sampling adequacy was 0.748, indicating acceptable sampling adequacy [83]. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (Chi-Square = 1.706, df = 15, p = 0.000), indicating sufficient correlation for factor analysis [84].

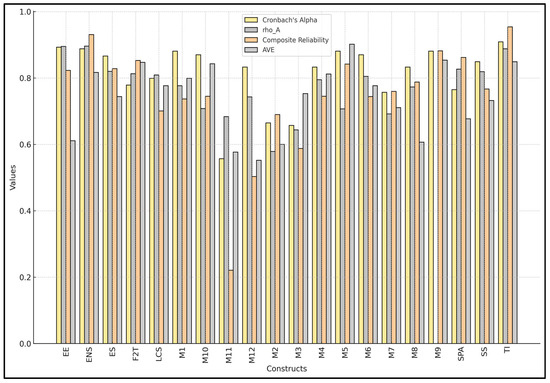

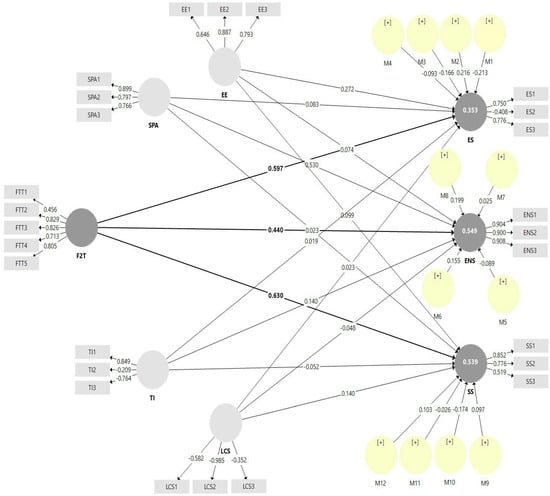

Smart PLS3 was utilized to do the SEM analysis. The R2 results indicate a good predictive power of the model. The results show that economic sustainability (ENS) explains 54.9%, environmental sustainability (ES) 35.3%, and social sustainability (SS) 53.9% of the variance. Model fit results show that the saturated model and estimated model have similar values, indicating satisfactory fit [83]. The SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) values are 0.101 for the saturated model and 0.105 for the estimated model, indicating good model–data alignment. The d_ULS (Unweighted Least Squares Discrepancy) is 0.549 for the saturated model and 0.857 for the estimated model, while the d_G (Geodesic Distance) is 0.203 for the saturated model and 0.272 for the estimated model. The Chi-Square values are 1.883 for the saturated model and 1.912 for the estimated model, and the NFI (Normed Fit Index) shows values of 0.917 for the saturated model and 0.901 for the estimated model. These results suggest that the model fits the data well and adequately describes the structure of relationships among variables. Cronbach’s alpha, rho_A, CR, AVE, HTMT, and VIF were used to assess the reliability and validity of the model [83].

Figure 6 indicates that the values of various reliability and validity indicators for all constructs are high, confirming their reliability and validity for further analysis. All Cronbach’s alpha values are above 0.7, indicating high internal consistency [84]. Similarly, high rho_A values confirm the consistency within constructs. Composite reliability also exceeds the 0.7 threshold, highlighting the overall reliability of the constructs [85]. Most of the average variance extracted (AVE) values are above 0.5, indicating satisfactory convergent validity [84].

Figure 6.

Construct reliability and validity.

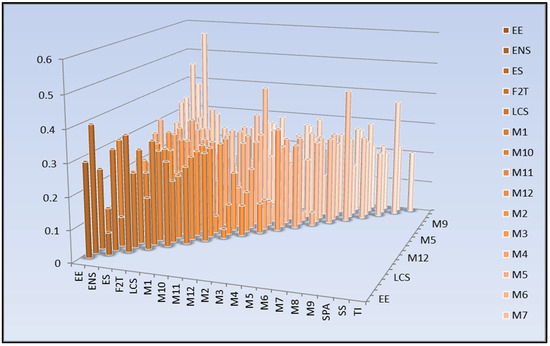

The results of the HTMT analysis show various levels of correlation between variables, indicating satisfactory discriminant validity for most constructs. Most values are below the threshold of 0.90, confirming that the constructs are generally valid and effectively differentiate between different concepts within the model [82] (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT).

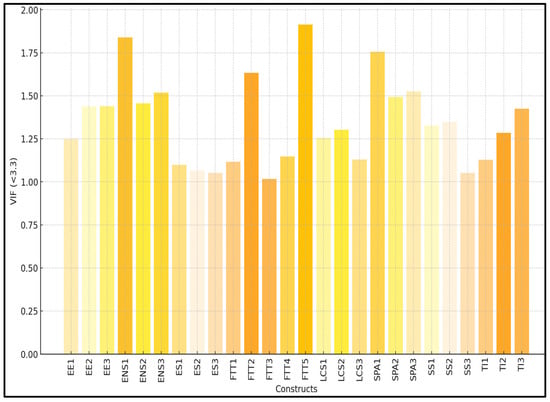

All VIF values are below the threshold of 3.3, indicating an acceptable level of variance and the absence of high multicollinearity among the independent variables [82,83] (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

VIF values for constructs.

3. Results

The research results are based on respondents’ perceptions of the impacts of the F2T concept and provide insights into respondents’ attitudes and opinions but do not quantify the actual implementations of F2T. The results presented in Table 4 show high average scores and satisfactory values for factor loadings (FL) and the coefficient of internal consistency (α). High average scores indicate a significant perception of the usefulness of the F2T concept among participants. Factor loadings are mostly above 0.7, confirming that the items are well connected to the latent constructs. The coefficient of internal consistency (α) is also mostly above 0.7, indicating a high level of reliability and consistency of the questionnaire. These findings suggest that the measured dimensions are valid and reliable for assessing the impact of the F2T concept on the sustainability of agritourism homesteads.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics, factor loadings, and internal consistency of F2T concept statements.

The results indicate that the F2T concept significantly enhances various aspects of sustainability on agritourism homesteads. Social sustainability is improved by strengthening the connections between local producers and consumers, increasing guests’ awareness of local traditions and culture, and creating educational programs for visitors. The F2T concept boosts economic sustainability by increasing income through direct sales, reducing transportation and distribution costs, and attracting new guests, which in turn increases the number of repeat visits. In terms of environmental sustainability, the concept reduces the ecological footprint, enhances soil quality and biodiversity, and promotes pollution reduction through composting and recycling. The F2T concept increases the attractiveness and recognition of homesteads, offers unique gastronomic experiences, and improves food quality with local products. The seasonal availability and diversity of products affect economic and environmental sustainability, highlighting the importance of adapting to seasonal changes. Employee education and training are crucial for implementing sustainable practices and improving social sustainability. Technological infrastructure supports economic and environmental sustainability by reducing waste and strengthening community connections. Finally, local community support significantly influences the economic and social sustainability of the F2T concept, emphasizing its key role in the success of agritourism initiatives.

Factor analysis was conducted to identify key sustainability factors. The results of the Promax rotation and factor loadings are presented, which help in understanding how variables are grouped into different factors [66]. Table 5 shows the total variance explained using the identified factors, as well as the eigenvalues for each factor. The Promax rotation was used because it allows for correlations between factors, which is useful in cases where the factors are conceptually related.

Table 5.

Factor analysis results.

Factor analysis identified eight key factors that explain a total of 70.87% of the variance in the data. Social sustainability (SS) has the highest initial eigenvalue of 6.111 and explains the largest percentage of variance (23.503%), indicating a significant impact on the connection between local producers and consumers, with an average rating of 3.87 and a high reliability (α = 0.895). Economic sustainability (ES) explains 12.148% of the variance, indicating an impact on increasing household income, with an average of 2.88 and high reliability (α = 0.879). Environmental sustainability (ENS) explains 11.080% of the variance, with an average of 2.66 and a high reliability (α = 0.891), indicating a significant impact on reducing the ecological footprint. The F2T concept explains 6.548% of the variance, with an average of 3.45 and a reliability (α = 0.764), indicating improved household attractiveness and food quality. Seasonal product availability (SPA) explains 4.958% of the variance, with an average of 3.12 and a high reliability (α = 0.884), indicating a significant impact on economic sustainability. Employee education (EE) explains 4.483% of the variance, with an average of 3.71 and a high reliability (α = 0.899), indicating an improvement in sustainable practices through training. Technological infrastructure (TI) explains 4.214% of the variance, with an average of 3.55 and a high reliability (α = 0.801), indicating improvements in economic and environmental sustainability through technology. Local community support (LCS) explains 3.942% of the variance, with an average of 3.77 and a high reliability (α = 0.822), indicating a significant impact on social sustainability. These results suggest that the identified factors are reliable and valid, providing a solid basis for the further analysis and interpretation of the research.

Table 6 presents the path coefficients and hypothesis testing results, indicating the strength and significance of the relationships between constructs. It includes the mean (m), standard deviation (sd), t-values, p-values, and confirmation status for each path. Hypotheses were tested using t-values, with a critical value set at 1.96 for a 95% confidence level. Values greater than 1.96 or less than −1.96 were deemed statistically significant. Additionally, p-values indicated the likelihood that the results occurred by chance, with a p-value less than 0.05 signifying statistical significance.

Table 6.

Path coefficients and hypothesis testing results.

The results show a significant positive impact of the F2T concept on the environmental sustainability (ENS) of agritourism homesteads (β = 0.440, p = 0.003), confirming hypothesis H1. Seasonal product availability (SPA) did not show a significant moderating effect on environmental sustainability (β = −0.089, p = 0.477), rejecting hypothesis H1a. In contrast, employee education (EE) showed a significant positive moderating effect (β = 0.155, p = 0.000), confirming hypothesis H1b and indicating that support for education and employment plays a crucial role in enhancing the positive impact of F2T concept on environmental sustainability. Technological infrastructure (TI) did not have a significant moderating effect (β = 0.025, p = 0.786), rejecting hypothesis H1c. Local community support (LCS) showed a significant positive moderating effect (β = 0.199, p = 0.011), confirming hypothesis H1d and suggesting that when the local community supports the F2T concept, it can amplify their positive impact on environmental sustainability.

Additionally, the results show a significant positive impact of the F2T concept on the economic sustainability (ES) of agritourism homesteads (β = 0.597, p = 0.000), confirming hypothesis H2. However, seasonal product availability (SPA) has a negative moderating effect on economic sustainability (β = −0.213, p = 0.016), suggesting that this impact may be diminished when seasonal products are readily available year-round, confirming hypothesis H2a. Employee education (EE) shows a positive moderating effect on the relationship between the F2T concept and economic sustainability (β = 0.216, p = 0.036), confirming hypothesis H2b and suggesting that support for education and employment enhances the positive effects of F2T concept. Technological infrastructure (TI) shows a negative moderating effect on this relationship (β = −0.166, p = 0.019), indicating that developed technological infrastructure may reduce the positive impact of the F2T concept on economic sustainability, confirming hypothesis H2c. Local community support (LCS) did not show a significant moderating effect on economic sustainability (β = −0.093, p = 0.448), rejecting hypothesis H2d.

The results show a significant positive impact of the F2T concept on the social sustainability (SS) of agritourism homesteads (β = 0.630, p = 0.000), confirming hypothesis H3. Seasonal product availability (SPA) positively moderates this relationship (β = 0.097, p = 0.002), confirming hypothesis H3a and suggesting that when seasonal products are more readily available, the F2T concept can have a stronger positive effect on social sustainability. Employee education (EE) did not show a significant moderating effect on social sustainability (β = −0.174, p = 0.372), rejecting hypothesis H3b. Technological infrastructure (TI) showed a significant negative moderating effect (β = −0.026, p = 0.001), suggesting that greater technological infrastructure may reduce the contribution of F2T practices to social sustainability in certain contexts, rejecting hypothesis H3c. Local community support (LCS) showed a significant positive moderating effect on the relationship between F2T and social sustainability (β = 0.103, p = 0.000), confirming hypothesis H3d and suggesting that when the local community supports the F2T concept, it can amplify their positive effect on social sustainability. Figure 9 introduces a structural equation modeling (SEM) diagram illustrating the relationships among various constructs related to the farm to table (F2T) concept and its impact on economic, environmental, and social sustainability in agritourism.

Figure 9.

Structural model with path coefficients and loadings.

4. Discussion

Although sustainable development is a broad concept, our work aims to provide insight into the specific impacts of the F2T concept on all three dimensions of sustainability. This approach is particularly important because ecological, economic, and social aspects often intertwine and influence each other. For example, ecological initiatives can have economic benefits by reducing costs and increasing attractiveness for tourists, while social aspects such as community support and employee education can further enhance ecological and economic benefits. Although the research findings are based on perceptions, they show that the F2T idea has a favorable impact on the economic, environmental, and social growth of agritourism homesteads. However, due to the subjective nature of the responses, more research using objective measurements is required to confirm these results. However, these effects are moderated using a variety of factors, including seasonal product availability, education and employment, technological infrastructure, and local community support.

Our focused analysis shows that the seasonal availability of products can have complex impacts on the economic sustainability of the F2T concept. Specifically, when seasonal products are available year-round, the demand for local seasonal products may decrease, potentially reducing the profitability of local farmers. This targeted finding highlights the importance of aligning seasonal availability with market demands to maintain economic benefits. This suggests that the constant availability of seasonal products could weaken the economic benefits of the F2T concept. On the other hand, support for education and employment significantly enhances the positive effects of the F2T concept on economic sustainability. When there is adequate support for education and employment, F2T initiatives become more effective, as education and employment not only help develop these initiatives but also promote awareness and engagement in sustainable practices. This is crucial for promoting sustainable agricultural practices. However, a developed technological infrastructure can have complex and sometimes negative effects on the economic sustainability of the F2T concept. More intensive resource use or other negative environmental impacts associated with advanced technology can neutralize the benefits that the F2T concept brings.

Economic sustainability within the F2T concept is achieved by improving the financial stability of agritourism households. Farm to table activities directly connect producers and consumers, increasing farmers’ revenues and creating new business opportunities. For example, the research by Joyner et al. [86] illustrates how agritourism creates synergy between agriculture and tourism, enabling the diversification of farm activities and preservation of cultural heritage. This approach not only boosts farm incomes but also attracts tourists seeking authentic local experiences, further stimulating local economies. Our research confirms these findings, indicating that the F2T concept significantly contributes to the financial stability of local communities. Similarly, Palmi et al. [87] emphasize the role of innovation in agritourism, where the combination of traditional and contemporary resources can enhance the authenticity and attractiveness of tourist destinations. This approach ensures that agritourism remains economically sustainable while simultaneously preserving cultural heritage. The positive effects of education and employment on ecological sustainability further confirm the importance of supporting education and employment to enhance the positive impacts of the F2T concept.

Local community support also plays a key role in promoting sustainable practices, as support for local farmers and the consumption of locally produced food can significantly boost environmental sustainability. The F2T concept is intrinsically linked to environmental sustainability, promoting practices that reduce the carbon footprint of agricultural activities. For example, the research by Coderoni et al. [88] highlights the importance of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture. Their study shows that higher levels of carbon productivity correlate with better economic efficiency, suggesting that sustainable practices not only benefit the environment but also increase farm profitability. Our research shows similar trends, where support for education and employment enhances the positive effects of the F2T concept on environmental sustainability, while technological infrastructure and seasonal product availability can have complex and sometimes negative effects. These findings are consistent with the research by Abdalla et al. [77], which emphasizes the importance of using nanomaterials in agricultural practices to support the F2T concept. Like our research, it confirms that sustainable agricultural practices supporting the F2T concept can significantly contribute to environmental sustainability and economic efficiency.

Social sustainability is a key aspect of the F2T concept, as it encourages community engagement and education about local food systems. The study by Patra et al. [68] on food waste emphasizes the importance of consumer education in reducing waste and improving food security, which directly contributes to social sustainability. Similarly, the research by Zakaria et al. [77] on nanofarming supports the F2T concept by improving productivity and biosecurity through the use of nanomaterials, thereby increasing resource efficiency and contributing to social sustainability through enhanced food security. Our findings align with these results, showing that local community support significantly enhances the positive effects of the F2T concept on social sustainability. In the context of agritourism in Brunei, Musa and Chin [70] investigate how F2T activities contribute to sustainable development by creating small- and medium-sized enterprises, preserving cultural heritage, and raising awareness about local food sources, all of which contribute to the social sustainability of the community. Our research supports these findings, showing that seasonal product availability and local community support positively influence the social sustainability of the F2T concept, further strengthening community ties. The research by Ibrahim Elshaer et al. [89] highlights the multifaceted role of agriculture, including agritourism, in promoting sustainable rural development, which is crucial for social sustainability. By combining traditional resources with innovations, new tourism and agricultural opportunities are created, contributing to social sustainability. Agritourism helps preserve cultural and natural heritage, increasing the authenticity and attractiveness of destinations, which further enhances the social sustainability of the community. Our results are consistent with these findings, as they show that support for education and employment significantly enhances the positive effects of the F2T concept on social sustainability, while technological infrastructure can have complex, and even negative, effects on social sustainability.

5. Conclusions

The goal of this study was to look at the impact of the F2T concept on the sustainability of agritourism homesteads in the Republic of Serbia, with an emphasis on economic, ecological, and social factors. Our results show that the “farm to table” concept can significantly contribute to specific aspects of sustainable development in agritourism homesteads. Although the approach is broad, we believe it is important to maintain a comprehensive view to better understand all the potential benefits and challenges of this concept. Further research can explore individual dimensions in more detail, but our work provides an important foundation for understanding the integrated approach to sustainability. The results demonstrated that the F2T concept can significantly contribute to specific aspects of sustainable development, particularly in improving economic and ecological sustainability. This targeted approach highlights its potential as an effective method for enhancing the rural economy and protecting the environment while recognizing the need for further research to explore broader impacts. Economic benefits include higher farmer incomes and new business prospects. The environmental benefits include a lower carbon footprint and improved resource management, while the social value of the F2T concept includes encouraging community involvement, consumer education, and cultural heritage preservation.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The theoretical implications of this research underscore the critical role of the F2T concept within the framework of sustainable development and agritourism. Despite frequent mentions in the literature, there is a notable gap in empirical studies that quantify its effects on various aspects of sustainability. Our findings contribute to this field by providing empirical evidence of the positive effects of the F2T concept on economic, environmental, and social sustainability. This research highlights the importance of the F2T concept in enhancing the financial stability of agritourism homesteads, improving resource management, and fostering community engagement. It also demonstrates the significant impact of moderators such as seasonal product availability, employee education, technological infrastructure, and local community support on the effectiveness of F2T initiatives. These findings open up new avenues for future research to explore these moderating effects in different contexts and regions, thereby expanding the understanding of the F2T concept’s potential to promote sustainable development.

This study provides a theoretical foundation for policymakers and practitioners to develop strategies that leverage the F2T concept to achieve sustainable rural development. By integrating economic, environmental, and social dimensions, the F2T concept can be positioned as a comprehensive approach to sustainability in agritourism. Future research can build on these theoretical insights to further investigate the long-term impacts of F2T initiatives and develop practical frameworks for their implementation in various geographical and cultural settings.

5.2. Practical Implications and Future Research Directions

The practical implications of this research are numerous. Farmers and agritourism operators can use the F2T concept as a strategy to increase their income and sustainability. Education and employment in agriculture have proven to be key factors that enhance the positive effects of the F2T concept, suggesting the need for training programs and support for farmers. Additionally, the results show that local community support can significantly improve the environmental and social effects of the perceived F2T concept, highlighting the importance of community engagement in these aspects. However, local community support did not show a significant impact on the economic sustainability of the F2T concept. Innovations in technology and the reduction in chemical use also play an important role in increasing sustainability, but it is crucial to carefully balance these innovations to avoid negative environmental impacts.

Future research should focus on quantifying the actual implementation of the F2T concept to overcome the limitations of this study, which relied on respondents’ perceptions. It is recommended to measure the percentage of locally sourced products and analyze economic, environmental, and social indicators before and after the implementation of the F2T concept. Additionally, qualitative methods such as interviews and case studies could provide deeper insights into the motivations, barriers, and perceptions of farmers and consumers regarding the F2T concept. Research conducted in different geographical contexts could offer comparative insights and aid in generalizing the findings. Studies that include objective metrics, such as actual data on income, costs, and environmental impact, would be crucial for a better understanding of the real effects of the F2T concept on the sustainability of agritourism homesteads. Research focusing on the long-term effects of F2T implementation could provide valuable information on how it influences sustainability over various time frames. These studies could include longitudinal research tracking changes in economic, environmental, and social indicators over multiple years. Future bibliometric studies should incorporate gray literature, such as reports, theses, and non-indexed conference papers. Additionally, expanding the dataset to include diverse publication types like book chapters and editorial materials could provide a more holistic view of the research landscape. This would ensure a more exhaustive analysis and broader insights into the topic.

5.3. Limitations

Despite the valuable insights provided by this study, there are limitations that need to be noted. The study was conducted in the specific geographical context of the Republic of Serbia, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other regions. The unique socioeconomic, cultural, and ecological factors of Serbia could have influenced the findings, and similar studies in different geographical areas might yield different results. Future research should focus on quantifying the actual implementation of the F2T concept to overcome the limitations of this study, which relied on participants’ perceptions. It is recommended to measure the percentage of locally sourced products and analyze economic, ecological, and social indicators before and after the implementation of the F2T concept. Additionally, qualitative methods such as interviews and case studies could provide deeper insights into the motivations, barriers, and perceptions of farmers and consumers regarding the F2T concept. Although this study covered all three dimensions of sustainability, we recognize that each of them is complex and that additional research could explore individual aspects in more detail. Our work represents a starting point for further research that could focus on specific dimensions of sustainability in different contexts.

Participants might overestimate or underestimate their practices and their impacts due to social desirability bias, recall bias, or other subjective factors. The research focused on the quantitative aspects of F2T concept, while future studies could include qualitative methods to gain a deeper understanding of the motivations, barriers, and perceptions of farmers and consumers regarding F2T concept. Utilizing interviews, focus groups, and case studies could provide richer and more detailed insights into the complexity and dynamics of the F2T concept.

Additionally, the main independent variable F2T was measured through respondents’ perceptions of various aspects of F2T concept, such as the attractiveness and recognizability of homesteads. These responses are subjective and do not reflect actual practices, such as the percentage of locally sourced or produced food ingredients. Subjective responses can carry a moral hazard, as respondents might be biased to maintain a positive image of their business, even if all food inputs come from a large wholesale market in a nearby city. It is important to note that the results of this study represent the participants’ perceptions and do not measure the direct impacts of the F2T concept. For a complete assessment of the impact of the F2T concept, further research involving direct measurements of relevant indicators is necessary.

To overcome the limitations of this study, future research should include objective measures that quantify the actual F2T concept. Although all variables were measured using a Likert scale, there is a valid criticism that certain variables, especially those related to the demographic and socioeconomic attributes of farmers, should not and could not be adequately measured in this way. For example, education should be measured by the level of education an individual has attained or by the number of years spent in formal education, rather than as a subjective assessment on a Likert scale. In our case, education is not a categorical variable, nor was the impact of farmers’ education on the responses measured. The variable “employee education” actually refers to attitudes towards education related to the implementation of the F2T concept. This approach measures respondents’ perceptions of the importance of education in the application of the F2T concept, rather than the actual education level of the employees. Furthermore, for each variable designated as a “moderator,” at least eight statements should be used to achieve a greater reliability and validity of the measures. Using only a few statements to measure these variables may be insufficient and can affect the accuracy of the research results. Our research did not include gray literature because the VOSviewer software version 1.6.20 does not support the analysis of such sources. This limitation may affect the comprehensiveness of our results, as relevant works outside indexed scientific databases were not considered. Although we relied on Web of Science (WoS) as the primary source for collecting research papers, we are aware of the limitations of this approach. There is a possibility that some inferior papers are included in this database, which may affect the comprehensiveness and quality of our findings. However, due to limited access to other databases, we chose Web of Science for its comprehensiveness and accessibility. We recommend that future research includes multiple databases to ensure an even greater accuracy and quality of the literature review.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G. and M.D.P.; methodology, I.B.; software, M.M.R.; validation, A.S., T.G., and D.S.; formal analysis, M.P.; investigation, D.D.B.; resources, D.A.D.; data curation, M.D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G.; writing—review and editing, M.P.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Contract no. 451-03-66/2024-03/200172), and by the RUDN University (Grant no. 060509-0-000). The research was also supported by The Provincial Secretariat for Higher Education and Scientific Research of Vojvodina (Grant No. 142-451-3466/2023-03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Holthaus, G. From the Farm to the Table: What All Americans Need to Know about Agriculture; University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeland, G.; Hettiarachchy, N.; Atungulu, G.; Apple, J.; Mukherjee, S. Strategies to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance from Farm to Table. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Yanac, T.; Nagadeepa, C.; Jaheer Mukthar, K.P.; Castillo-Picón, J.; Manrique-Cáceres, J.; Ramirez-Asis, E.; Huerta-Soto, C. Minimalist Farm-To-Table Practices: Connecting Consumers with Local Agriculture. In Technology and Business Model Innovation: Challenges and Opportunities; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KQED. Swanton Berry Farm: Bringing Justice to the Table. Available online: https://www.kqed.org/beyondtheplate/food-justice-certified-farms (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- RAFI-USA. The Agricultural Justice Project’s “Food Justice Certified” Label. Available online: https://www.rafiusa.org/food-justice-certified-label (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Gottlieb, R.; Joshi, A. Food Justice; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41474631 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Horst, M.; McClintock, N.; Hoey, L. The intersection of planning, urban agriculture, and food justice: A review of the literature. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2017, 83, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohio Ecological Food and Farm Association (OEFFA). Food Justice Certification. 2020. Available online: https://certification.oeffa.org/food-justice-certification/ (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- AgFunder. Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education. 2022. Available online: https://research.agfunder.com/2022-agfunder-agrifoodtech-investment-report.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Boz, I.; Kılıç, O.; Kaynakci, C. Rural Tourism Contributions to Rural Development in the Eastern Black Sea Region of Turkey. Int. J. Sci. Res. Manag. 2018, 6, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arabska, E. From Farm to Fork: Human Health and Well-Being Through Sustainable Agri-Food Systems. J. Life Econ. 2021, 8, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damnjanović, A.; Živanović, N.; Vasilkov, Z. Strategy “From Field to Table”: Attempt of Symbiosis of Food Production and Ecology in the European Union. Ecologica 2022, 29, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyshev, K.A.; Alov, I.N.; Li, Y.; Gajić, T. How Real Is Migration’s Contribution to the Population Change in Major Urban Agglomerations? J. Geogr. Inst. Cvijic. 2023, 73, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Factsheet: From Farm to Fork: Our Food, Our Health, Our Planet, Our Future. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/fs_20_908 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Meng, F.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, H.; Shao, Z.; Jian, Y.; Mao, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q. Carotenoid Biofortification in Tomato Products along Whole Agro-Food Chain from Field to Fork. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukolić, D.; Gajić, T.; Petrović, M.D.; Bugarčić, J.; Spasojević, A.; Veljović, S.; Vuksanović, N.; Bugarčić, M.; Zrnić, M.; Knežević, S.; et al. Development of the Concept of Sustainable Agro-Tourism Destinations—Exploring the Motivations of Serbian Gastro-Tourists. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirato, S.; Felicetti, A.M. The Agritourism as a Means of Sustainable Development for Rural Communities: A Research from the Field. Int. J. Interdiscip. Environ. Stud. 2014, 8, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolac, R.; Adamov, T.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Lile, R.; Rujescu, C.; Marin, D. Agritourism-A Sustainable Development Factor for Improving the ‘Health’ of Rural Settlements. Case Study Apuseni Mountains Area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Brad, I.; Popescu, G.; Marin, D.; Adamov, T. Agritourism Activity—A “Smart Chance” for Mountain Rural Environment’s Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro-Hurle, J.; Bogonos, M.; Himics, M.; Elleby, C. Modelling Environmental and Climate Ambition in the Agricultural Sector with the CAPRI Model; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotz, S.; Fraser, E.D.G. Resilience and the Industrial Food System: Analyzing the Impacts of Agricultural Industrialization on Food System Vulnerability. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2015, 5, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C. Agritourism Research: A Perspective Article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengilimoğlu, D.; Zekioğlu, A.; Tosun, N.; Işık, O.; Tengilimoğlu, O. Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic Period on Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Levels of the Healthcare Employees in Turkey. Legal Med. 2021, 48, 101811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.K.; Lee, D.; Jeong, J.; Moon, J. The Effect of Agritourism Experience on Consumers’ Future Food Purchase Patterns. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Thornton, P.K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Palmer, J.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Pradhan, P.; Barrett, C.B.; Benton, T.G.; Hall, A.; Pikaar, I.; et al. Articulating the Effect of Food Systems Innovation on the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e50–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajić, T.; Vukolić, D.; Đoković, F.; Jakovljević, M.; Bugarčić, J.; Jošanov Vrgović, I.; Glišić, S. Application of the PPM Model in Assessing the Impact of Economic Factors on the Selection of an Agro-Tourism Destination after COVID-19. Econ. Agric. 2023, 3, 755–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Mariani, A. Consumer Perception of Sustainability Attributes in Organic and Local Food. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 2018, 9, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, W.; Luo, W.; Li, M.; Chu, F.; Duan, X. Stretchable Transparent Electrode Arrays for Simultaneous Electrical and Optical Interrogation of Neural Circuits in Vivo. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 2903–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssell, S.; Lankoski, L. The Sustainability Promise of Alternative Food Networks: An Examination through “Alternative” Characteristics. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicetti, A.M.; Ammirato, S.; Corvello, V.; Iazzolino, G.; Verteramo, S. Total Quality Management and Corporate Social Responsibility: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemics. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, V.S.; Figueiredo, E.; McAllister, T.; Stanford, K. Farm to Fork Impacts of Super-Shedders and High-Event Periods on Food Safety. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 127, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, J. Factors Associated with the Profitability of Agritourism Operations: Evidence from an Eastern Chinese County. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P.B.; Ejiogu, K.; Karki, L.B.; Escobar, E.N.; Arbab, N.N.; Kairo, M.T. Factors Associated with the Profitability of Agritourism Operations in Maryland, USA. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagi, F.S.; Reeder, R.J. Factors Affecting Farmer Participation in Agritourism. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2012, 41, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addinsall, C.; Scherrer, P.; Weiler, B.; Glencross, K. An Ecologically and Socially Inclusive Model of Agritourism to Support Smallholder Livelihoods in the South Pacific. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurgat, B.K.; Lamanna, C.; Kimaro, A.; Namoi, N.; Manda, L.; Rosenstock, T.S. Adoption of Climate-Smart Agriculture Technologies in Tanzania. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollenburg, C.; Buckley, R.C. Stated Economic and Social Motivations of Farm Tourism Operators. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, O.M.; Cohen, A.L.; Reganold, J.P.; Jones, M.S.; Orpet, R.J.; Taylor, J.M.; Thurman, J.H.; Cornell, K.A.; Olsson, R.L.; Ge, Y.; et al. Landscape Context Affects the Sustainability of Organic Farming Systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 2870–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peț, E.; Popescu, G.; Șmuleac, L. Sustainability of Agritourism Activity: Initiatives and Challenges in Romanian Mountain Rural Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro-Visconti, R. From Farm to Table: Sustainable AgriFoodTech and ESG Compliance. 2022. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366391328_From_Farm_to_Table_Sustainable_AgriFoodTech_and_ESG_compliance (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Holland, R.; Khanal, A.R.; Dhungana, P. Agritourism as an Alternative On-Farm Enterprise for Small U.S. Farms: Examining Factors Influencing the Agritourism Decisions of Small Farms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastronardi, L.; Giaccio, V.; Giannelli, A.; Scardera, A. Is Agritourism Eco-Friendly? A Comparison between Agritourisms and Other Farms in Italy Using Farm Accountancy Data Network Dataset. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscardo, G.; Konovalov, E.; Murphy, L.; McGehee, N.G.; Schurmann, A. Linking Tourism to Social Capital in Destination Communities. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, R.; Martinez, P.; Ahmad, R. The Digitization of Agricultural Industry—A Systematic Literature Review on Agriculture 4.0. Smart Agric. Technol. 2022, 2, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blešić, I.; Petrović, M.; Gajić, T.; Tretiakova, T.; Vujičić, M.; Syromiatnikova, J. Application of the analytic hierarchy process in the selection of traditional food criteria in Vojvodina (Serbia). J. Ethn. Foods 2021, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togaymurodov, E.; Roman, M.; Prus, P. Opportunities and Directions of Development of Agritourism: Evidence from Samarkand Region. Sustainability 2023, 15, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitt, C.; Low, S.A.; Van Sandt, A. Agritourism Allows Farms to Diversify and Has Potential Benefits for Rural Communities. Amber Waves Magazine; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2019/november/agritourism-allows-farms-to-diversify-and-has-potential-benefits-for-rural-communities/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Donaldson, A. Digital from Farm to Fork: Infrastructures of Quality and Control in Food Supply Chains. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 91, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, L.; Culasso, F.; Truant, E. Unlocking Value Creation Using an Agritourism Business Model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.M.; Kubickova, M. Agritourism Microbusinesses within a Developing Country Economy: A Resource-Based View. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toni, A.; Vizzarri, M.; Di Febbraro, M.; Lasserre, B.; Noguera, J.; Di Martino, P. Aligning Inner Peripheries with Rural Development in Italy: Territorial Evidence to Support Policy Contextualization. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Khairabadi, O. Leveraging Agritourism in Rural Areas in Developing Countries: The Case of Iran. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 863385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.D.; Milovanović, I.; Gajić, T.; Kholina, V.N.; Vujičić, M.; Blešić, I.; Đoković, F.; Radovanović, M.M.; Ćurčić, N.B.; Rahmat, A.F.; et al. The Degree of Environmental Risk and Attractiveness as a Criterion for Visiting a Tourist Destination. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tey, Y.S.; Li, E.; Bruwer, J.; Abdullah, A.M.; Brindal, M.; Radam, A.; Ismail, M.M.; Darham, S. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices in Developing Countries: A Review. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2017, 16, 219–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortignani, R.; Buttinelli, R.; Dono, G. Farm to Fork Strategy and Restrictions on the Use of Chemical Inputs: Impacts on the Various Types of Farming and Territories of Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 810, 152259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offermann, F.; Nieberg, H.; Zander, K. Dependency of Organic Farms on Direct Payments in Selected EU Member States: Today and Tomorrow. Food Policy 2009, 34, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Solangi, Y.A. Analyzing and Prioritizing the Barriers and Solutions of Sustainable Agriculture for Promoting Sustainable Development Goals in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, V.; Arias, J.; Dürr, J.; Elverdin, P.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Kinengyere, A.; Opazo, C.M.; Owoo, N.; Page, J.R.; Prager, S.D. A Scoping Review on Incentives for Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices and Their Outcomes. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paarlberg, R. The Trans-Atlantic Conflict over “Green” Farming. Food Policy 2022, 108, 102229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Minasyan, L.A.; Petrović, M.D.; Bakhtin, V.A.; Kaneeva, A.V.; Wiegel, N.L. Travelers’ (in)Resilience to Environmental Risks Emphasized in The Media and Their Redirecting to Medical Destinations: Enhancing Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiffoleau, Y. From Politics to Co-operation: The Dynamics of Embeddedness in Alternative Food Supply Chains. Sociol. Rural. 2009, 49, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadonna, A.; Matozzo, A.; Giachino, C.; Peira, G. Farmer Behavior and Perception Regarding Food Waste and Unsold Food. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugarčić, J.; Cvijanović, D.; Vukolić, D.; Zrnić, M.; Gajić, T. Gastronomy as an Effective Tool for Rural Prosperity—Evidence from Rural Settlements in Republic of Serbia. Econ. Agric. 2023, 70, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirato, S.; Felicetti, A.M.; Raso, C.; Pansera, B.A.; Violi, A. Agritourism and Sustainability: What We Can Learn from a Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachão, S.; Breda, Z.; Fernandes, C.; Joukes, V. Food Tourism and Regional Development: A Systematic Literature Review. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseler, J.H.H. The EU’s Farm-to-Fork Strategy: An Assessment from the Perspective of Agricultural Economics. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2022, 44, 1826–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M.K.; Rauniyar, S.; Kapoor, S.; Mishra, A.K. Agritourism: Structured Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 46, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinić, B.M.; Jevremov, T. Trends in Research Related to the Dark Triad: A Bibliometric Analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 40, 3206–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]