Impact of Linking Livelihood Resilience of Smallholder Households and the Risk Management Strategies: The Case of China from Socioeconomic Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Area

2.2. Data Sources

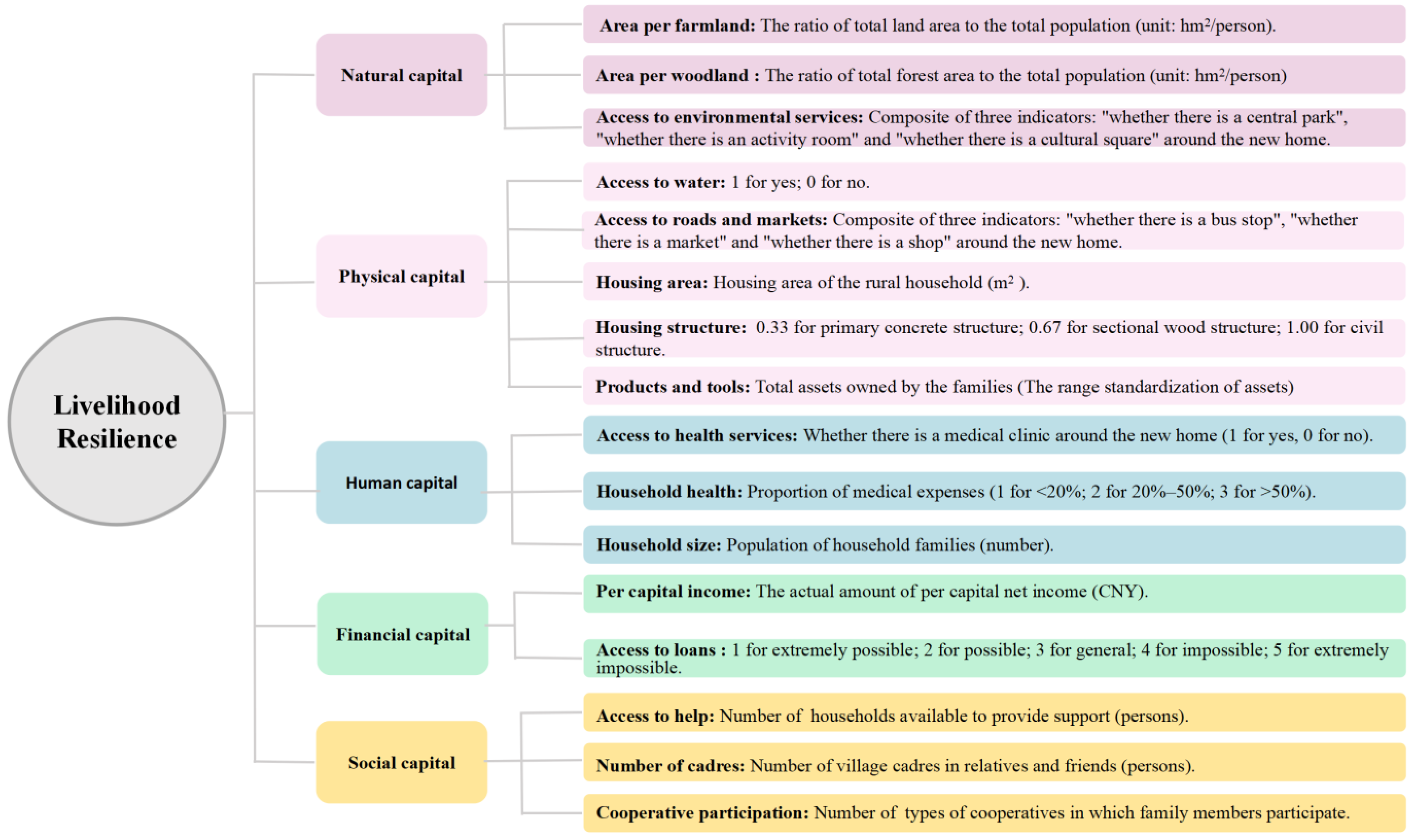

2.3. Indicator Construction

- Livelihood resilience capital assets and detailed indicators

- 2.

- Relocation characteristics

- 3.

- Follow-up support measures

- 4.

- Risk management strategy

- 5.

- Covariates for Coarsened Exact Matching

2.4. Research Methods

2.4.1. Coarsened Exact Matching

2.4.2. Multinomial Logit Regression Model

3. Results and Analysis

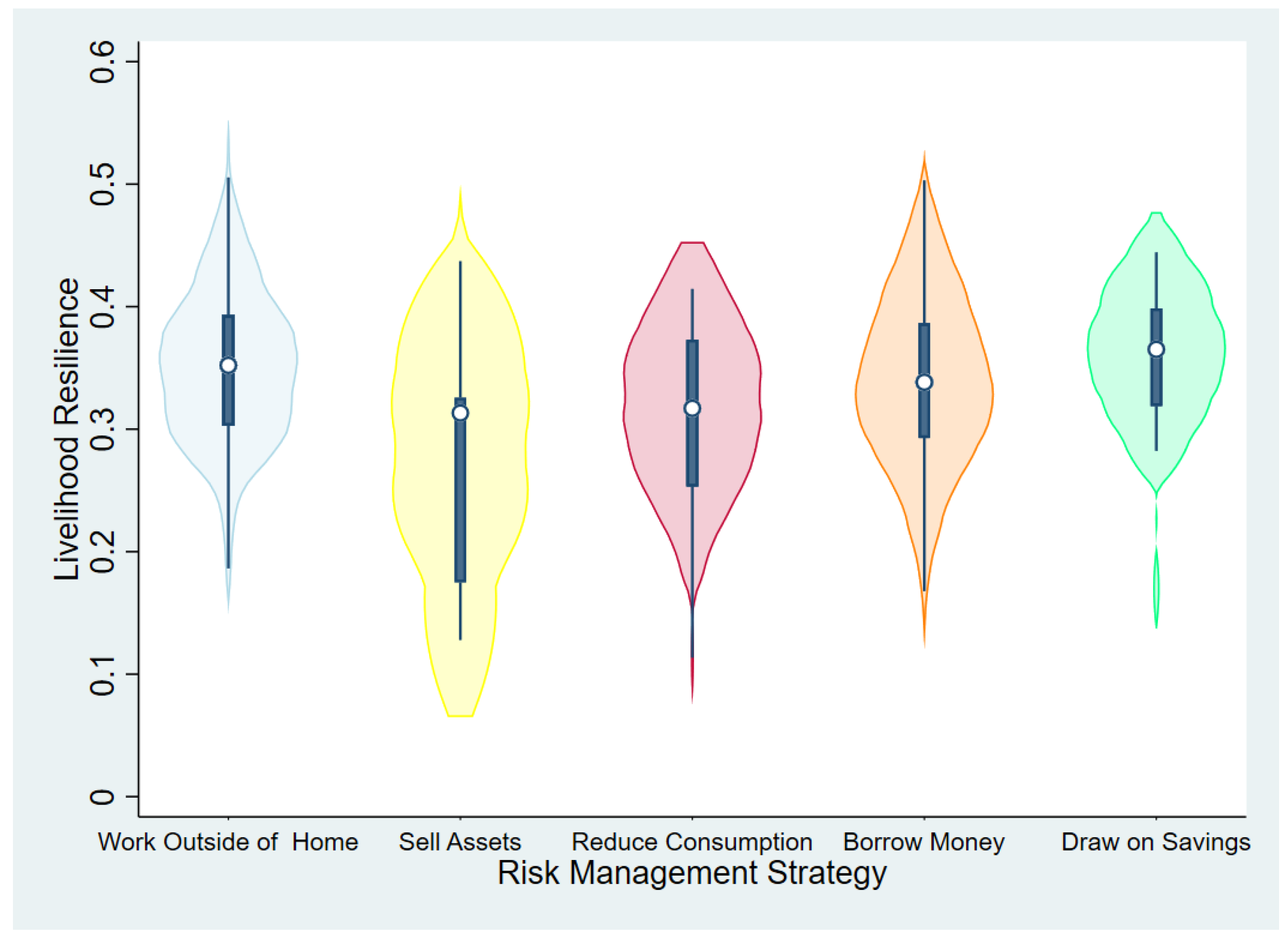

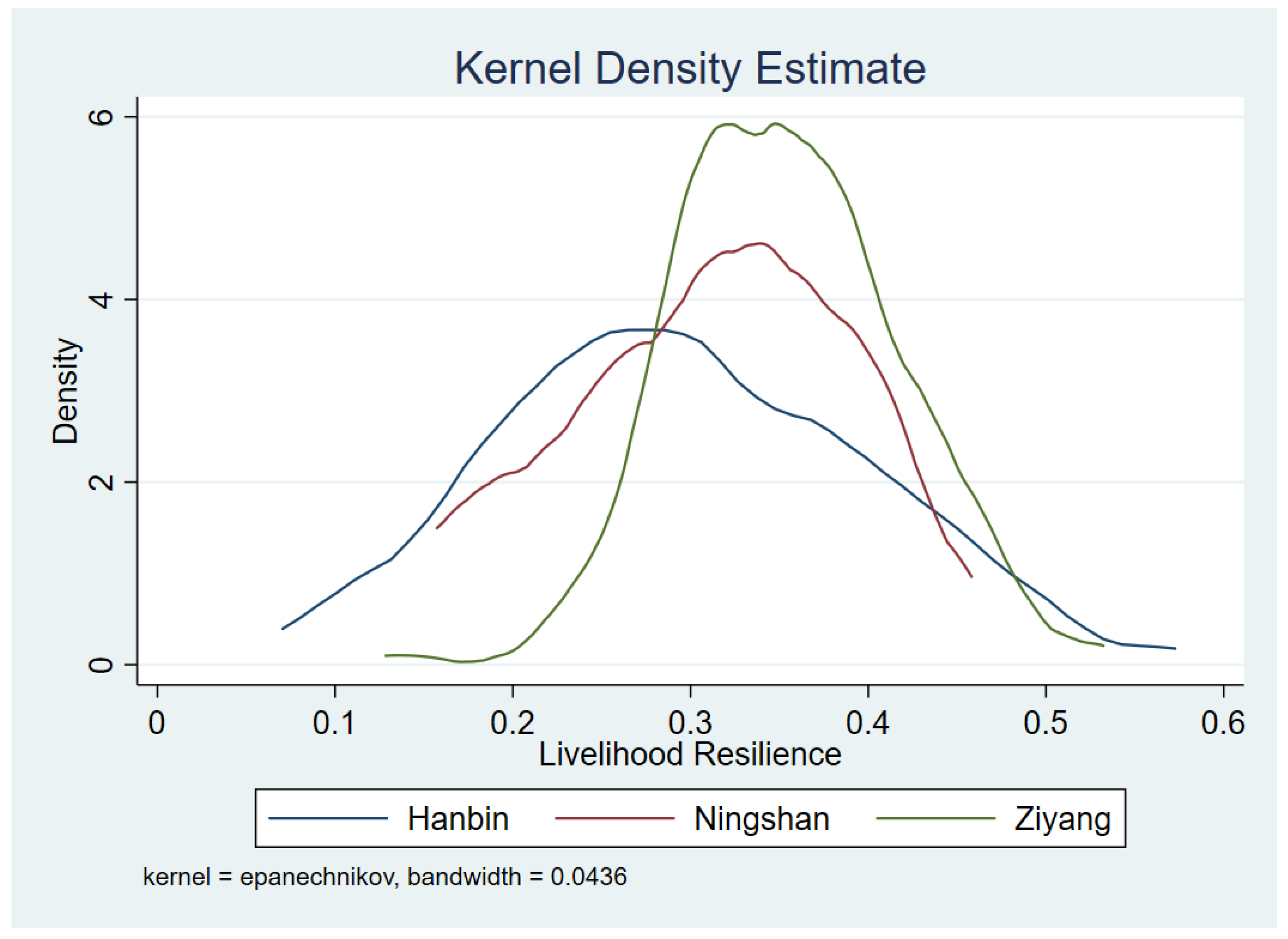

3.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Livelihood Resilience of Households with Different Characteristics

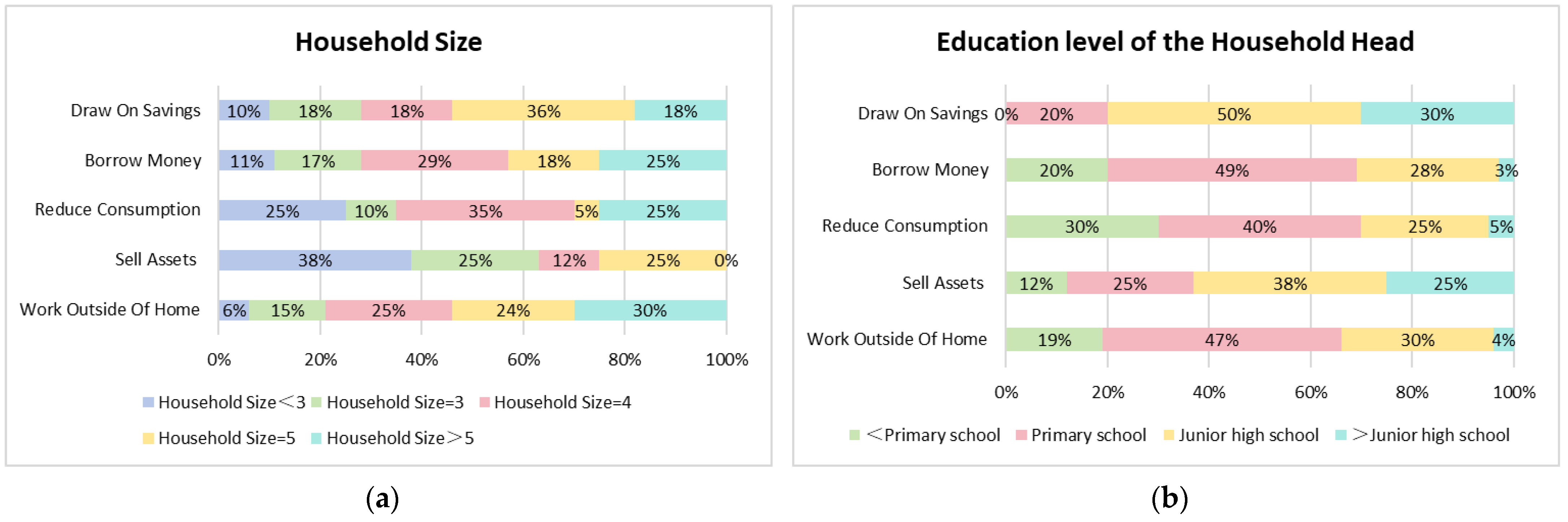

3.2. Analysis of the Choice of Risk Management Strategies with Different Family Characteristics

4. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Choice of Risk Management Strategies for Disaster Resettlement Households

4.1. Analysis of the Impact of Households’ Livelihood Resilience and Its Dimensions on Risk Management Strategies

4.2. Analysis of the Impact of Households’ Livelihood Resilience Indicators on Risk Management Strategies

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lo, K.; Wang, M. How voluntary is poverty alleviation resettlement in China. Habitat Int. 2018, 73, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Li, Y. Targeted poverty alleviation and land policy innovation: Some practice and policy implications from China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Project-induced displacement and resettlement: From impoverishment risks to an opportunity for development? Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tan, Y.; Luo, Y. Post-disaster resettlement and livelihood vulnerability in rural China. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2017, 26, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, J.K. A new path forward: Researching and reflecting on forced displacement and resettlement: Report on the international resettlement conference: Economics, social justice, and ethics in development-caused involuntary migration, the Hague, 4–8 October 2010. J. Refug. Stud. 2012, 25, 193–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Li, S.Z. Rural Households’ Poverty and Relocation and Settlement: Evidence from Western China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmsen, B. After the deluge: A longitudinal study of resettlement at the Three Gorges Dam, China. World Dev. 2016, 84, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Kapucu, N. Examining livelihood risk perceptions in disaster resettlement. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2017, 26, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Kapucu, N. Examining the impacts of disaster resettlement from a livelihood perspective: A case study of Qinling Mountains, China. Disasters 2018, 42, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miani, A.M.; Dehkordi, M.K.; Siamian, N.; Lassois, L.; Tan, R.; Azadi, H. Toward sustainable rural livelihoods approach: Application of grounded theory in Ghazni province, Afghanistan. Appl Geogr. 2023, 154, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Pouliot, M.; Walelign, S.Z. Livelihood strategies and dynamics in rural Cambodia. World Dev. 2017, 97, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnall, A.; Thomas, D.S.; Twyman, C.; Liverman, D. Flooding, resettlement, and change in livelihoods: Evidence from rural Mozambique. Disasters 2013, 37, 468–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usamah, M.; Haynes, K. An examination of the resettlement program at Mayon Volcano: What can we learn for sustainable volcanic risk reduction? Bull. Volcanol. 2012, 74, 839–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zheng, H.; Li, S.Z.; Chen, X.S.; Li, J.; Zeng, W.H.; Liang, Y.C.; Polasky, S.; Feldman, M.W.; Ruckelshaus, M.; et al. Impacts of conservation and human development policy across stakeholders and scales. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 112, 7396–7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1973, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. Global environmental change I: A social turn for resilience? Prog. Hum. Geog. 2014, 38, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, A. Measuring livelihood resilience: The household livelihood resilience approach (HLRA). World Dev. 2018, 107, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, T.; Lewis, D.; Wrathall, D.; Bronen, R.; Cradock-Henry, N.; Huq, S.; Lawless, C.; Nawrotzki, R.; Prasad, V.; Rahman, M.A.; et al. Livelihood resilience in the face of climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulstrup, A.W. Livelihood resilience and adaptive capacity: Tracing changes in household access to capital in Central Vietnam. World Dev. 2015, 74, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sina, D.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R. A conceptual framework for measuring livelihood resilience: Relocation experience from Aceh, Indonesia. World Dev. 2019, 117, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, C.I.; Wiesmann, U.; Rist, S. An indicator framework for assessing livelihood resilience in the context of social–ecological dynamics. Global. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebboth, M.G.L.; Conway, D.; Adger, W.N. Mobility endowment and entitlements mediate resilience in rural livelihood systems. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 54, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamwanza, A.M. Livelihood resilience and adaptive capacity: A critical conceptual review. Jamba-J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2012, 4, 1–6. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC128737 (accessed on 27 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.P.; Zhu, F.B.; Qiu, X.P.; Zhao, S. Effects of natural disasters on livelihood resilience of rural residents in Sichuan. Habitat Int. 2018, 76, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Xu, J. Effects of disaster-related resettlement on the livelihood resilience of rural households in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 49, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, J.L. Managing Risk in Farming: Concepts, Research, and Analysis; US Department of Agriculture, ERS: Washington, DC, USA, 1999.

- OECD. Managing Risk in Agriculture: A Holistic Approach; OECD: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Fan, P.; Liu, Y. What makes better village development in traditional agricultural areas of China? Evidence from long-term observation of typical villages. Habitat Int. 2019, 83, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezeer, R.E.; Verweij, P.A.; Boot, R.G.; Junginger, M.; Santos, M.J. Influence of livelihood assets, experienced shocks and perceived risks on smallholder coffee farming practices in Peru. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 242, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U.; Ansari, M.A.; Ghosh, S. Measures of livelihoods and their effect on vulnerability of farmers to climate change: Evidence from coastal and non-coastal regions in India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 4801–4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglio, G.; Karapiperis, T.; Van Woensel, L.; Arnold, E.; McDaid, D. Austerity and health in Europe. Health Policy 2013, 113, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannigrahi, S.; Zhang, Q.; Joshi, P.K.; Sutton, P.C.; Keesstra, S.; Roy, P.S.; Pilla, F.; Basu, B.; Wang, Y.; Jha, S.; et al. Examining effects of climate change and land use dynamic on biophysical and economic values of ecosystem services of a natural reserve region. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savari, M.; Amghani, M.S. SWOT-FAHP-TOWS analysis for adaptation strategies development among small-scale farmers in drought conditions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 67, 102695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babulo, B.; Muys, B.; Nega, F.; Tollens, E.; Nyssen, J.; Deckers, J.; Mathijs, E. Household livelihood strategies and forest dependence in the highlands of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Agric. Syst. 2008, 98, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Hasan, K.; Kabir, K.H. Determinants of households’ livelihood vulnerability due to climate induced disaster in southwest coastal region of Bangladesh. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2022, 15, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnani, T.; Gotor, E.; Caracciolo, F. Adaptive strategies enhance smallholders’ livelihood resilience in Bihar, India. Food Secur. 2021, 13, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.J.; Pritchard, B. Financial capital as a shaper of households’ adaptive capabilities to flood risk in northern Bangladesh. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 195, 107381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Deng, X.; Guo, S.; Liu, S. Sensitivity of livelihood strategy to livelihood capital: An empirical investigation using nationally representative survey data from rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 144, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.P.; Fan, J.; Shen, M.Y.; Song, M.Q. Sensitivity of livelihood strategy to livelihood capital in mountain areas: Empirical analysis based on different settlements in the upper reaches of the Minjiang River, China. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 38, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.M.; Lorenzen, K.A.I. Livelihood diversification in rural Laos. World Dev. 2016, 83, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Deng, W.; Song, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Su, Y.; Lu, Y. Spatio-temporal impact of rural livelihood capital on labor migration in Panxi, southwestern mountainous region of China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Tian, X.; Zheng, Y.P. Analysis of the impact of livelihood risk on farmers’ coping strategies. J. China Agric. Univ. 2018, 23, 226–240. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Qing, C.; Deng, X.; Yong, Z.L.; Zhou, W.F.; Ma, Z.X. Disaster Risk Perception, Sense of Pace, Evacuation Willingness, and Relocation Willingness of Rural Households in Earthquake-Stricken Areas: Evidence from Sichuan Province, China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 17, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerda, A.; Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Gimenez-Morera, A.; Keesstra, S.D. An economic, perception and biophysical approach to the use of oat straw as mulch in Mediterranean rainfed agriculture land. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 108, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, A.; Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Gimenez-Morera, A.; Keesstra, S.D. Hydrological and erosional impact and farmer’s perception on catch crops and weeds in citrus organic farming in Canyoles river watershed, Eastern Spain. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 258, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ren, L.J.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Li, S.Z. Exploring livelihood resilience and its impact on livelihood strategy in rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 977–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Feldman, M. Livelihood adaptive capacities and adaptation strategies of relocated households in rural China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1067649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarza-Villamar, J.A.; Leeuwis, C.; Pila-Quinga, G.M.; Cecchi, F.; Parraga-Lema, C.M. Local understanding of disaster risk and livelihood resilience: The case of rice smallholders and floods in Ecuador. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choden, K.; Keenan, R.J.; Nitschke, C.R. An approach for assessing adaptive capacity to climate change in resource dependent communities in the Nikachu watershed, Bhutan. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 114, 106293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Guo, S.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. Livelihood resilience and strategies of rural residents of earthquake-threatened areas in Sichuan Province, China. Nat. Hazards 2021, 106, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, A.M.; Rafique, M.Z.; Bakhsh, K.; Makhdum, M.S.A.; Huang, S. Impact of socio-economic and water access conditions on life satisfaction of rural farmers in Faisalabad district of Pakistan. Water Policy 2020, 22, 686–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, F.; Jin, J.; He, R.; Ning, J.; Wan, X. Farmers’ livelihood risks, livelihood assets and adaptation strategies in Rugao City, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Livelihood adaptation strategy and perceived adaptive capacity of rural relocated households in Southern Shaanxi Province, China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 26, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mutabazi, K.D.; Amjath-Babu, T.S.; Sieber, S. Influence of livelihood resources on adaptive strategies to enhance climatic resilience of farm households in Morogoro, Tanzania: An indicator-based analysis. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2015, 15, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.J.; Wheeler, T. Adaptive governance: Livelihood innovation for climate resilience in Uganda. Geoforum 2015, 65, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sina, D.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R. What does the future hold for relocated communities post-disaster? Factors affecting livelihood resilience. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2019, 34, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, W.S.; Patch, B.; Reddy, V.R.; Syme, G.J. Modelling livelihoods and household resilience to droughts using Bayesian networks. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 18, 315–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacus, S.M.; King, G.; Porro, G. Causal inference without balance checking: Coarsened exact matching. Political Anal. 2012, 20, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacus, S.M.; King, G.; Porro, G. Multivariate matching methods that are monotonic imbalance bounding. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2011, 106, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, V.; Mannering, F. An exploratory multinomial logit analysis of single-vehicle motorcycle accident severity. J. Safety Res. 1996, 27, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Land use and adaptive governance under climate change: Analysis of four cases in pastoral areas of China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 922417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xue, H.; Zhao, X.; Tang, H. Linking livelihood assets of smallholder households to risk management strategies: An empirical study in China. Environ. Hazards 2019, 18, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Q.; Yang, Q. Public health insurance, non-farm labor supply, and farmers’ income: Evidence from New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukul, S.A.; Rashid, A.Z.M.; Uddin, M.B.; Khan, N.A. Role of non-timber forest products in sustaining forest-based livelihoods and rural households’ resilience capacity in and around the protected area: A Bangladesh study. J. Environ. Plan Manag. 2016, 59, 628–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Rogers, S.; Li, J.; Li, C. Farmers to urban citizens? Understanding resettled households’ adaptation to urban life in Shaanxi, China. Cities 2024, 145, 104667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators | New-Stage | Early-Stage | Centralized | Noncentralized | T1-Test | T2-Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | |||

| Area per farmland | 0.094 | 0.223 | 0.044 | 0.095 | 0.083 | 0.212 | 0.063 | 0.107 | −2.573 | −0.933 |

| Area per woodland | 0.259 | 1.605 | 0.293 | 1.289 | 0.177 | 0.458 | 0.583 | 3.050 | 0.221 | 2.356 |

| Access to environmental services | 0.552 | 0.350 | 0.544 | 0.370 | 0.589 | 0.344 | 0.405 | 0.354 | −0.219 | −4.781 |

| Access to water | 0.997 | 0.056 | 0.929 | 0.258 | 0.972 | 0.166 | 0.990 | 0.098 | −4.429 | 1.087 |

| Access to roads and markets | 0.838 | 0.260 | 0.754 | 0.342 | 0.855 | 0.256 | 0.655 | 0.346 | −2.877 | −6.431 |

| Housing area | 149.713 | 75.268 | 168.199 | 94.196 | 152.661 | 71.863 | 163.409 | 108.515 | 2.235 | 1.184 |

| Housing structure | 0.970 | 0.121 | 0.905 | 0.209 | 0.960 | 0.143 | 0.917 | 0.189 | −4.139 | −2.505 |

| Products and tools | 0.331 | 0.123 | 0.355 | 0.114 | 0.331 | 0.114 | 0.361 | 0.137 | 1.976 | 2.265 |

| Access to health services | 0.930 | 0.256 | 0.922 | 0.269 | 0.960 | 0.195 | 0.818 | 0.387 | −0.293 | −5.077 |

| Household health | 2.369 | 0.769 | 2.269 | 0.766 | 2.349 | 0.792 | 2.321 | 0.686 | −1.094 | −0.288 |

| Household size | 4.519 | 1.546 | 4.433 | 1.649 | 4.506 | 1.559 | 4.533 | 1.704 | −0.540 | 0.156 |

| Per capital income | 5786.462 | 6206.817 | 5344.223 | 6309.873 | 5242.768 | 5963.697 | 6960.538 | 6954.015 | −0.699 | 2.492 |

| Access to loans | 2.421 | 1.313 | 2.493 | 1.344 | 2.374 | 1.325 | 2.689 | 1.285 | 0.533 | 2.154 |

| Access to help | 4.011 | 4.850 | 3.386 | 4.984 | 4.012 | 5.233 | 3.139 | 3.355 | −1.260 | −1.613 |

| Number of cadres | 0.358 | 1.109 | 0.369 | 1.065 | 0.407 | 1.167 | 0.236 | 0.811 | 0.096 | −1.408 |

| Cooperative participation | 0.019 | 0.137 | 0.085 | 0.485 | 0.029 | 0.197 | 0.105 | 0.536 | 2.213 | 2.223 |

| Sample size | 314 | 141 | 354 | 105 | ||||||

| Relocation Characteristics | Relocation Time | Relocation Nature | Settlement Approach | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New-Stage | Early-Stage | Voluntary | Involuntary | Centralized | Noncentralized | |

| High-HLR | 78 | 35 | 105 | 8 | 93 | 20 |

| (26.441%) | (25.362%) | (28.000%) | (13.333%) | (27.596%) | (20.408%) | |

| Medium-HLR | 138 | 57 | 173 | 23 | 151 | 45 |

| (46.780%) | (41.304%) | (46.133%) | (38.333%) | (44.807%) | (45.918%) | |

| Low-HLR | 79 | 46 | 97 | 29 | 93 | 33 |

| (26.780%) | (33.333%) | (25.867%) | (48.333%) | (27.596%) | (33.673%) | |

| Total | 295 | 138 | 375 | 60 | 337 | 98 |

| Relocation Characteristics | Relocation Time | Relocation Nature | Settlement Approach | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New-Stage | Early-Stage | t-Test | Voluntary | Involuntary | t-Test | Centralized | Noncentralized | t-Test | |

| Livelihood resilience | 0.348 | 0.338 | −1.272 | 0.351 | 0.302 | 5.180 *** | 0.349 | 0.330 | −2.390 ** |

| Natural capital assets | 0.040 | 0.038 | −0.943 | 0.042 | 0.026 | 4.759 *** | 0.042 | 0.030 | −4.635 *** |

| Physical capital assets | 0.137 | 0.130 | 3.565 *** | 0.137 | 0.121 | 5.973 *** | 0.136 | 0.129 | −3.314 *** |

| Human capital assets | 0.116 | 0.117 | 0.307 | 0.118 | 0.105 | 3.269 *** | 0.118 | 0.109 | −2.723 *** |

| Financial capital assets | 0.046 | 0.047 | 0.277 | 0.047 | 0.043 | −0.850 | 0.044 | 0.054 | 2.762 *** |

| Social capital assets | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.236 | 0.007 | 0.006 | −0.861 | 0.008 | 0.006 | −0.920 |

| Risk Management Strategy | High-HLR | Medium-HLR | Low-HLR | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work outside of home | 63 | 115 | 65 | 243 |

| (16.406%) | (29.948%) | (16.927%) | (63.281%) | |

| Sell assets | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 |

| (0.260%) | (1.042%) | (0.781%) | (2.083%) | |

| Reduce consumption | 2 | 8 | 8 | 18 |

| (0.521%) | (2.083%) | (2.083%) | (4.688%) | |

| Borrow money | 25 | 46 | 33 | 104 |

| (6.510%) | (11.979%) | (8.594%) | (27.083%) | |

| Draw on savings | 4 | 5 | 2 | 11 |

| (1.042%) | (1.302%) | (0.521%) | (2.865%) | |

| Total | 95 | 178 | 111 | 384 |

| (24.740%) | (46.354%) | (28.906%) | (100%) |

| Variables | Work Outside of Home | Sell Assets | Reduce Consumption | Draw on Savings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whether relocated | −1.348 ** | 2.844 * | 2.996 ** | −2.439 ** |

| (−2.55) | (1.85) | (2.20) | (−2.42) | |

| Livelihood resilience | 8.185 *** | −16.940 ** | −9.460 * | 11.823 ** |

| (3.01) | (−2.42) | (−1.69) | (2.20) | |

| Age | −0.506 * | 0.310 | 0.247 | −0.088 |

| (−1.85) | (0.35) | (0.41) | (−0.18) | |

| Average years of education | 0.227 ** | 0.215 | −0.224 | 0.586 *** |

| (2.44) | (0.76) | (−1.22) | (2.80) | |

| Livelihood diversification | 0.350 * | −0.574 | 0.265 | 0.440 |

| (1.89) | (−0.93) | (0.70) | (1.16) | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1259 | |||

| Whether relocated | −1.755 ** | 3.274 ** | 3.362 ** | −1.878 |

| (−2.44) | (2.02) | (2.05) | (−1.43) | |

| Natural capital assets | −1.348 | −22.859 | −9.567 | −28.052 * |

| (−0.18) | (−1.30) | (−0.74) | (−1.95) | |

| Physical capital assets | 25.740 ** | −24.941 | −34.664 * | 53.543 ** |

| (2.32) | (−0.93) | (−1.93) | (2.11) | |

| Human capital assets | 9.737 * | −15.273 | 9.589 | 9.398 |

| (1.75) | (−1.05) | (0.85) | (0.92) | |

| Financial capital assets | 7.935 | 3.082 | −18.904 | 16.765 |

| (1.30) | (0.15) | (−1.13) | (1.31) | |

| Social capital assets | −18.025 | 7.359 | −43.165 | 19.439 |

| (−1.08) | (0.17) | (−0.61) | (0.77) | |

| Age | −0.495 * | 0.047 | 0.233 | −0.169 |

| (−1.76) | (0.05) | (0.37) | (−0.33) | |

| Average years of education | 0.226 ** | 0.190 | −0.198 | 0.541 |

| (2.37) | (0.66) | (−1.04) | (2.51) | |

| Livelihood diversification | 0.309 | −0.689 | 0.207 | 0.336 |

| (1.61) | (−0.92) | (0.50) | (0.84) | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1680 | |||

| Variables | Work Outside of Home | Sell Assets | Reduce Consumption | Draw on Savings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whether relocated | −2.450 ** | 0.040 | 1.927 | −4.704 | |

| (−1.98) | (0.00) | (0.54) | (−1.54) | ||

| Livelihood resilience | Area per farmland | −5.658 * | −6.637 | −30.542 | 8.743 ** |

| (−1.76) | (−0.00) | (−1.43) | (2.28) | ||

| Area per woodland | 64.004 * | −8.694 | 80.433 ** | 86.674 ** | |

| (1.89) | (−0.00) | (2.23) | (2.42) | ||

| Access to environmental services | −0.227 | −0.985 | −1.560 | −3.694 ** | |

| (−0.36) | (−0.01) | (−1.10) | (−2.10) | ||

| Access to water | 1.306 | −0.112 | −1.641 | 2.422 | |

| (1.58) | (−0.00) | (−0.88) | (0.79) | ||

| Access to roads and markets | 0.857 | 1.031 | −4.503 | 1.166 | |

| (0.67) | (0.00) | (−1.45) | (0.41) | ||

| Housing area | −1.524 | −3.588 | −17.090 | 1.670 | |

| (−0.82) | (−0.00) | (−1.54) | (0.40) | ||

| Housing structure | −1.675 | −0.415 | −1.804 | 1.193 | |

| (−1.02) | (−0.00) | (−0.36) | (0.26) | ||

| Products and tools | 5.243 *** | 3.489 | 9.110 * | 11.016 *** | |

| (2.95) | (0.01) | (1.70) | (2.71) | ||

| Access to health services | 1.239 | −0.864 | 5.917 | −2.433 | |

| (1.33) | (−0.00) | (1.47) | (−0.98) | ||

| Household health | −0.418 | 1.543 | −1.157 | −0.395 | |

| (−0.52) | (0.01) | (−0.56) | (−0.19) | ||

| Household size | 2.331 ** | −5.597 | −7.327 * | 4.621 | |

| (2.08) | (−0.01) | (−1.85) | (1.60) | ||

| Per capital income | 2.171 | 5.318 | 8.092 | 0.119 | |

| (0.32) | (0.00) | (0.78) | (0.02) | ||

| Access to loans | 0.908 | 0.041 | −3.893 | 1.002 | |

| (1.26) | (0.00) | (−1.49) | (0.53) | ||

| Access to help | −4.350 | −7.846 | −2.398 | 0.857 | |

| (−1.57) | (−0.00) | (−0.23) | (0.21) | ||

| Number of cadres | 1.237 | −0.231 | −4.842 | 6.235 | |

| (0.37) | (−0.00) | (−0.28) | (1.31) | ||

| Cooperative participation | −2.500 | 1.591 | −112.121 | 1.004 | |

| (−1.12) | (0.00) | (−0.00) | (0.24) | ||

| Relocation characteristics | Relocation time | 0.950 ** | −0.336 | −0.328 | 0.958 |

| (2.03) | (−0.00) | (−0.26) | (0.52) | ||

| Relocation nature | 0.186 | −0.163 | −0.282 | 6.065 ** | |

| (0.28) | (−0.00) | (−0.14) | (2.25) | ||

| Settlement approach | −0.116 | 0.936 | 1.099 | 1.351 | |

| (−0.20) | (0.00) | (0.67) | (0.68) | ||

| Follow-up support measures | Industrial support | 0.206 | −0.006 | 1.775 | −0.984 |

| (0.56) | (−0.00) | (1.61) | (−0.67) | ||

| Employment support | −0.118 | 0.121 | 1.432 | 0.389 | |

| (−0.31) | (0.00) | (1.11) | (0.31) | ||

| Training | −0.453 | −0.659 | −3.710 ** | 0.518 | |

| (−1.55) | (−0.00) | (−2.19) | (0.71) | ||

| Age | −0.575 * | −0.223 | −0.135 | 0.077 | |

| (−1.83) | (−0.00) | (−0.13) | (0.12) | ||

| Average years of education | 0.242 ** | −0.153 | −0.251 | 0.701 ** | |

| (2.13) | (0.00) | (−0.92) | (2.30) | ||

| Livelihood Diversification | 0.031 | −0.732 | 0.101 | −0.503 | |

| (0.13) | (−0.01) | (0.13) | (−0.75) | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.4076 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Song, Z.; Xu, J.; Feng, W.; Liu, W. Impact of Linking Livelihood Resilience of Smallholder Households and the Risk Management Strategies: The Case of China from Socioeconomic Perspectives. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14091599

Liu X, Song Z, Xu J, Feng W, Liu W. Impact of Linking Livelihood Resilience of Smallholder Households and the Risk Management Strategies: The Case of China from Socioeconomic Perspectives. Agriculture. 2024; 14(9):1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14091599

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xinming, Zhe Song, Jie Xu, Weilin Feng, and Wei Liu. 2024. "Impact of Linking Livelihood Resilience of Smallholder Households and the Risk Management Strategies: The Case of China from Socioeconomic Perspectives" Agriculture 14, no. 9: 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14091599

APA StyleLiu, X., Song, Z., Xu, J., Feng, W., & Liu, W. (2024). Impact of Linking Livelihood Resilience of Smallholder Households and the Risk Management Strategies: The Case of China from Socioeconomic Perspectives. Agriculture, 14(9), 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14091599