Abstract

The black soil in northeast China plays an important role in coping with global climate change. However, long-term predatory production methods and the excessive application of pesticides and fertilizers to respond to the growing demand resulted in a severe contamination of the black soil with Cd, leading to a decrease in the properties of black soil. In this study, we propose the preparation of bio-adsorbents including a natural bio-adsorbent (AW), a modified bio-adsorbent (AM), biochar cracking at 300, 500, and 700 °C (C300, C500, C700), modified biochar (CM), and a magnetic bio-adsorbent particle (MBP) using the waste of black soil autotrophic specialty crop multiplier onion (Allium cepa var. aggregatum) to investigate the adsorption and immobilization of Cd in contaminated soil. The results show that the application of bio-adsorbents resulted in a 17.29–35.67% and 18.24–30.76% decrease in effective and total Cd content in soil after dry–wet–freeze circulation. Exchangeable Cd in soil decreased and gradually transformed to more stable fractions, with a reduction in Cd bioavailability after remediation. Interestingly, an increase in plant uptake of Cd was observed in the biochar-treated group for a short period, causing a 93.72% increase in Cd concentration in plants after the application of C700, which can be applied concomitantly with hyperaccumulator plants harvested multiple times annually by encouraging higher Cd uptake by plants. Additionally, the rich content of humic acid (HA) in black soil was capable of promoting the immobilization of Cd in soil, enhancing the Cd resistance of black soil. Bio-adsorbents derived from Allium cepa var. aggregatum waste can be applied as a new type of green and effective material for the long-term remediation of Cd in the soil at a lower cost.

1. Introduction

Cd is recognized as a priority pollutant due to its long-range environmental mobility, strong neurotoxicity, difficult degradability, and bioaccumulation [1]; its biological half-life is as long as 16–30 years and may lead to acute and chronic toxicity or even damage to mental health to humans [2,3]. Currently, global soil Cd contamination presents a critical situation, with 10 million tons of crop yield loss per year caused by heavy metal contamination [4].

Black soil is known as ‘the giant panda of cultivated land’ because of its high carbon and organic matter, excellent soil structure, looseness, and porosity. The black soil of northeastern China is one of the world’s major black soil belts, with a total area of about 10 million ha, making it an important food production site in China [5]. However, uncontrolled Cd-containing fertilizer and pesticide abuse, unprotected mining and improper recovery, Cd-containing industrial solid waste dumping and disposal, and toxic and hazardous wastewater irrigation and infiltration are gradually eroding the black soil [6,7,8]. Increasing soil pollution and spreading solid waste are threatening human health and future global food production [4].

The special climate of Northeast China contributes to the dry–wet–freeze–thaw interaction of black soil, which affects Cd2+ transport and transformation behavior by altering the formation, stabilization, and decomposition of soil aggregates [9,10,11]. Freeze–thaw interaction influences the pH, cation exchange capacity, and free iron oxide and calcium carbonate contents of the soil, which increases the content of exchangeable calcium and magnesium ions, and enhances the competitive adsorption of Cd2+ while promoting chelation between Cd2+ and functional groups [12,13].

To contribute to the response to global climate change and to achieve carbon peaking, agricultural wastes are gradually being applied to environmental remediation [14,15,16,17,18]. Biomass materials, biochar, and magnetic adsorbents derived from agricultural wastes have been shown to be effective in soil Cd adsorption and immobilization, which can reduce Cd bioavailability while improving soil pH, organic carbon, and nutrients [19,20]. Research indicated that phosphoric acid- and urea-modified cotton stalk biochar reduced the available Cd content in soil by 51.68–63.40%, significantly promoted the transformation of acid-soluble Cd to reducible, oxidizable, and residual Cd, reducing the bioavailability of Cd [21]. The addition of 1% biochar prepared from wheat straw fermented by T. asperellum T-1 under 600 °C reduced the bioavailability of Cd in rice soil by 83.7% after 15 days [22]. The application of magnetic adsorbents ensures the adsorption efficiency and at the same time resolves the difficulty of the complete separation of pollutants and adsorbents from the soil. The application of magnetic hydroxyapatite-loaded biochar effectively reduces the bioavailable Cd and total cadmium content in the soil, and increases grain yield by increasing the nutrient content of the soil [23]. In addition, HA and its composites in black soil can also effectively reduce the effective state of Cd in soil [10,11].

Multiplier onion (Allium cepa var. aggregatum), as one of the specialty crops in Jilin Province, with a yield of about 6000 kg/acre, is widely cultivated in the black soil region of Northeast China. In addition, multiplier onions are grown on a commercial scale in Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and India. It is commonly grown in home gardens in Europe, North America, the Caucasus, Kazakhstan, and south-eastern Russia [24]. In this study, natural and modified bio-adsorbents, biochar cracking at different temperatures, modified biochar, and magnetic adsorbents were prepared from Allium cepa var. aggregatum waste with the aim of investigating: (1) the adsorption properties and mechanism of Cd2+; (2) the transport and transformation of Cd2+ between soil and adsorbents under the characteristic wet–dry–freeze conditions experienced by black soil in northeast China; (3) the immobilization and passivation effects of adsorbents on Cd in black soil; (4) the effect of adsorbents on the bioavailability of Cd in soil; (5) the contribution of HA to Cd contamination resistance in black soil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of Adsorbents

The methodology and processes of this research are shown in Figure S1. Allium cepa var. aggregatum skin waste (mainly composed of onion skins) was collected in Jilin Province, China, with the variety of “Nongan”, which is typically planted in April and harvested in July every year in northeastern China. The waste was cleaned and dried at 80 °C, pulverized, and passed through 20-mesh and 140-mesh sieves to obtain AW@20 and AW@140, respectively. Modified adsorbent (AM) was obtained using 0.1 mol/L NaOH at a solid–liquid ratio of 1:10. Biochar preparation was carried out in a tube furnace under a N2 atmosphere with temperature settings of 300, 500, and 700 °C at a temperature increase rate of 10 °C/min to obtain C300, C500, and C700, respectively. To enhance the adsorption efficiency of low-temperature biochar at a low cost, C300 was modified using 0.1 mol/L KMnO4 at a solid–liquid ratio of 1:20 to obtain modified biochar (CM) according to previous research and comparative experiments [16,17]. Totals of 10.0 g of FeSO4·7H2O and 10.0 g of FeCl3·6H2O were dissolved in 200 mL water, and 10.0 g of AW@140 was then added to the solution followed by 5.0 mol/L NaOH, which was used to adjust the pH until 13 to ensure complete precipitation. The mixture was then stirred for 8 h and immobilized for 12 h. The solid precipitate acquired after centrifugation was washed and dried at 65 °C to obtain magnetic bio-adsorbent particles (MBP). Meanwhile, the effect of HA on the remediation of black soil was explored along with bio-adsorbents. The HA used in this experiment was of chemical purity, obtained from the Tianjin Guangfu Fine Chemical Research Institute.

Ash content (burning at 800 °C for 4 h), pH (1:20 water extraction), and electrical conductivity (EC, 1:100 water extraction) were analyzed. The functional groups on the surface of the adsorbent were identified using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, NICOLET iS10, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM-IT200, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) was used for surface morphology observation. A surface area and porosity analyzer (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA, ASAP 2020Plus) was employed to obtain the specific surface area (SSA) and pore structure of adsorbents. The magnetic characterization of MBP was determined using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM, Lakeshore, Carson, CA, USA, 7404). The concentration of Cd2+ was determined using atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS, A3-AFG, Persee, Beijing, China).

2.2. Investigation of Adsorption Capacity and Mechanism of Cd2+

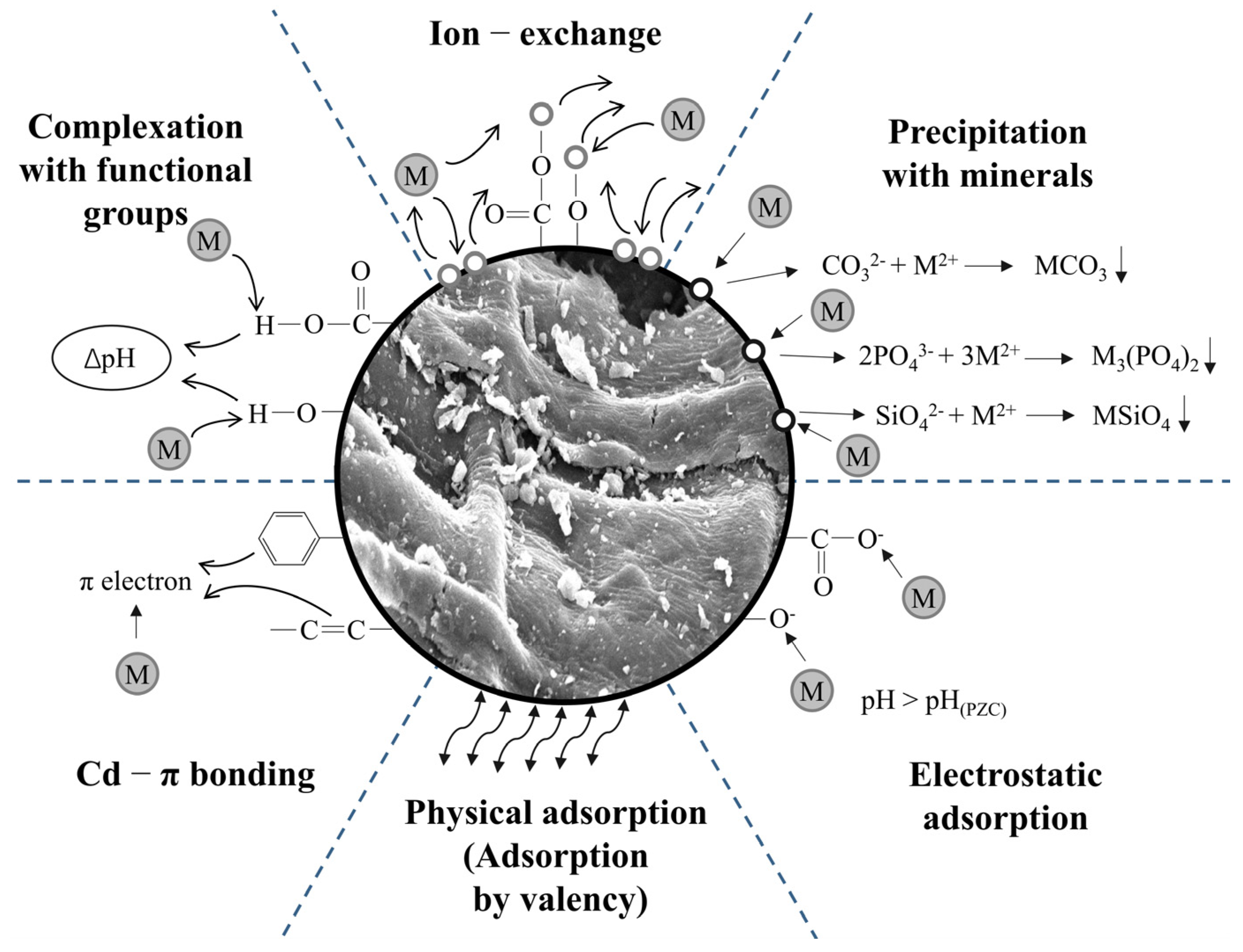

The experiments were carried out and the data were collected in 2024. Batch adsorption experiments were carried out to investigate the adsorption rate and adsorption capacity for the Cd2+ of bio-adsorbents. The quantitative calculation of the contribution to different mechanisms of Cd(II) was determined based on a combination of the method proposed by Wang [25] and the method improved by Cui [26]. The mechanisms mainly include ion exchange (), complexation with acidic functional groups (), precipitation with minerals (), and other mechanisms () including Cd–π interactions () and physical adsorption, where and were included in the interactions with minerals () (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adsorption mechanism of Cd2+ by adsorbents.

A total of 2.0000 g of bio-adsorbent was weighed and added to 50 mL of a mixed solution of 0.1 mol/L HCl + 10% HF, and the mixture was then placed on a 170 rpm/min oscillator for 8 h. This step was repeated twice to ensure the complete desorption of the mineral components. The acidified bio-adsorbent was washed with ultrapure water to stabilize the pH of the leach solution and dried to obtain the demineralized adsorbent, which was weighed to calculate the yield of acidification. The difference in the amount of Cd2+ adsorbed before and after demineralization can be considered as the contribution of minerals. The original and acidified bio-adsorbents were weighed separately for Cd2+ adsorption experiments, and the contents of cations and pH changes in the solution were measured. can be calculated by the value of the decrease in the pH of the solution before and after adsorption, and the specific calculation methodology was as follows:

where is the total amount of Cd2+ adsorbed by the original adsorbent, mg/g; is the amount of Cd2+ adsorbed by the acidified adsorbent, mg/g; Y is the yield of demineralized adsorbent; , , , and are the net amount of ions released from the adsorbents into solution, respectively, and the calculation was normalized to Cd2+, mg/g.

2.3. Preparation of Cd-Contaminated Soil

The experimental black soil was collected from the western part of Changchun City, Jilin Province (43°54′25″ N, 125°6′42″ E). The overlying plants were removed and the top 5–40 cm of soil was collected. Anthropogenic contamination of the soil was carried out using cadmium acetate, with the contamination lasting for 90 days, during which the soil was stirred regularly to prevent consolidation. The Cd concentration in the final contaminated soil was 129.80 mg/kg. The basic properties of the original soil S0 and the contaminated soil SCd are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic properties of soil.

2.4. Transport of Cd2+ Between Soil and Adsorbents Under Wet–Dry–Freeze Conditions

Wet–dry–freeze circulations were conducted indoors to simulate the temperature and moisture changes of the actual environment experienced by black soil in northeast China, and to observe the adsorption and removal of Cd2+ in the contaminated soil by bio-adsorbents. A modified three-layer grid method was used in this experiment for the complete separation of bio-adsorbents from soil after remediation, where the mass ratio of adsorbents and contaminated soil was 1:10 [27]. The specific experimental setup, temperature, and time settings of wet–dry–freeze are described in the Supplementary Materials. At the end of the 3rd, 6th, and 10th circulations of wet–dry–freeze, soil samples were acquired, after which total Cd was extracted by mixed acid, and available Cds (DTPA-Cd and TCLP-Cd) were extracted by C14H23N3O10 − N(CH2CH2OH)3 − CaCl2 and CH3COOH, respectively (see the Supplementary Materials).

2.5. Transformation of Cd in Soil and Pot Experiments

A total of 300 g of contaminated soil was placed in plastic cups with permeable holes at the bottom at a diameter of 80 mm and a height of 90 mm, and different proportions of adsorbents were added followed by saturation of the soil (1%, 2%, and 3% of AW@140, C500, MBP, and HA, 2% of AW@20, AM, C300, C700, and CM). Daily weighing was performed to maintain the soil water-holding capacity for 45 days. The fractions of Cd were analyzed using the Tessier method (Table 2) [28] and available Cd was determined at the same time. Subsequently, pot experiments were conducted on the soil after 45 days of remediation. Seeds of Brassica juncea were provided by Shuxin Seed Industry. A direct seeding method was implemented in this study by sowing the seeds directly into the soil for cultivation. Harvesting was carried out 30 days after sowing, and the edible parts were analyzed for Cd content followed by the bioconcentration factor (BCF), which was calculated correspondingly as described in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 2.

Procedure of Tessier sequential extraction method (1.0000 g soil).

3. Results and Discussion

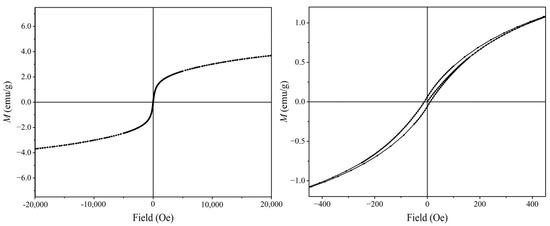

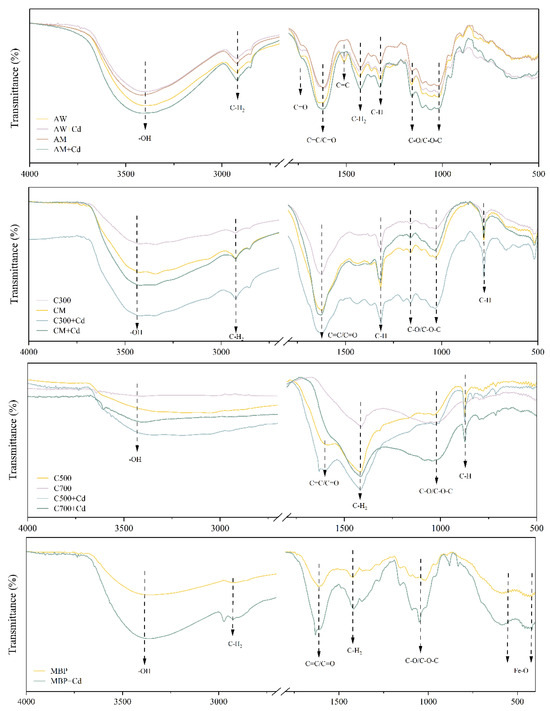

3.1. Properties and Adsorption Capacity of Adsorbents

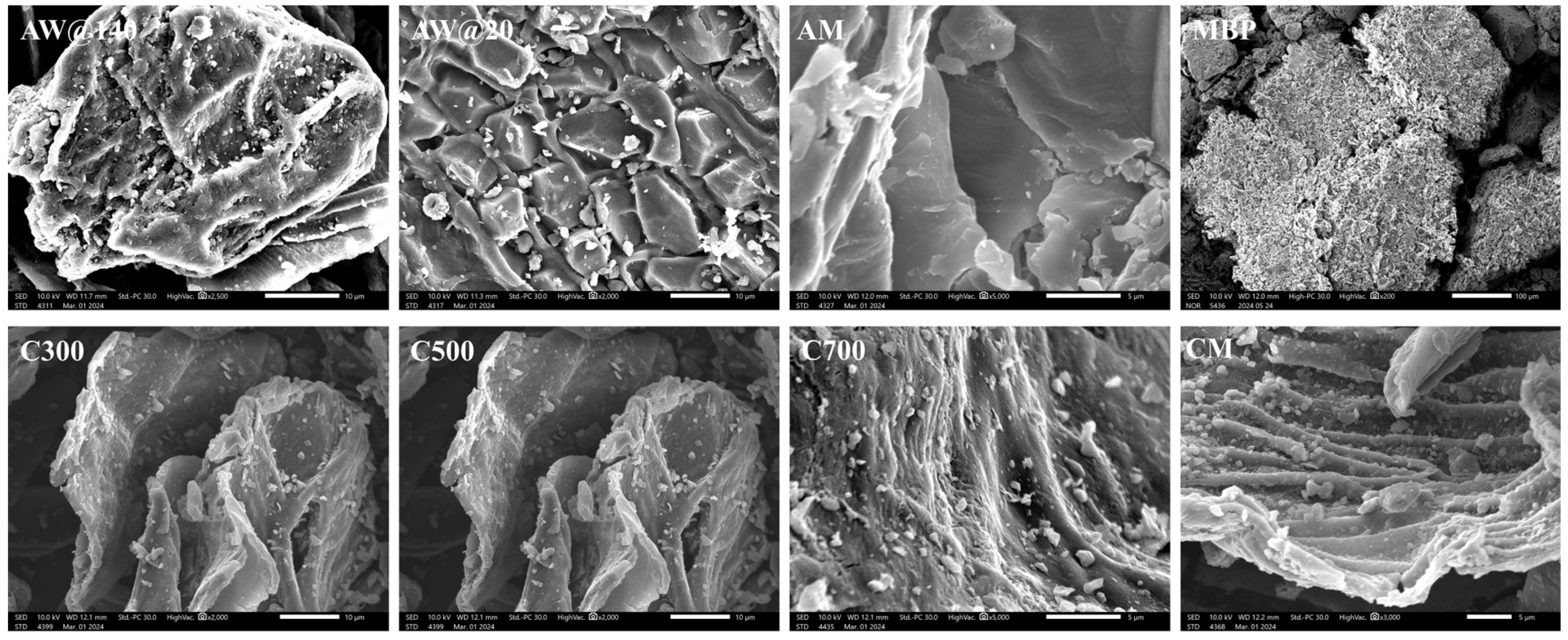

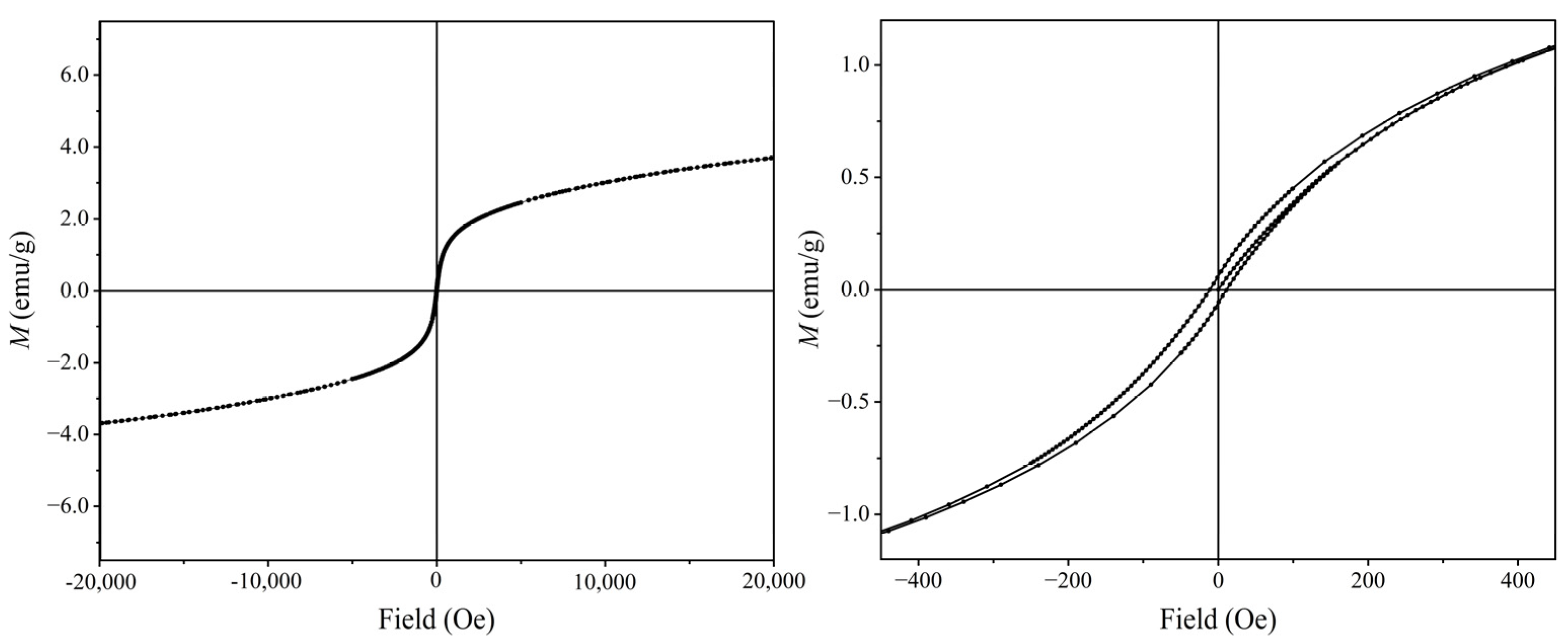

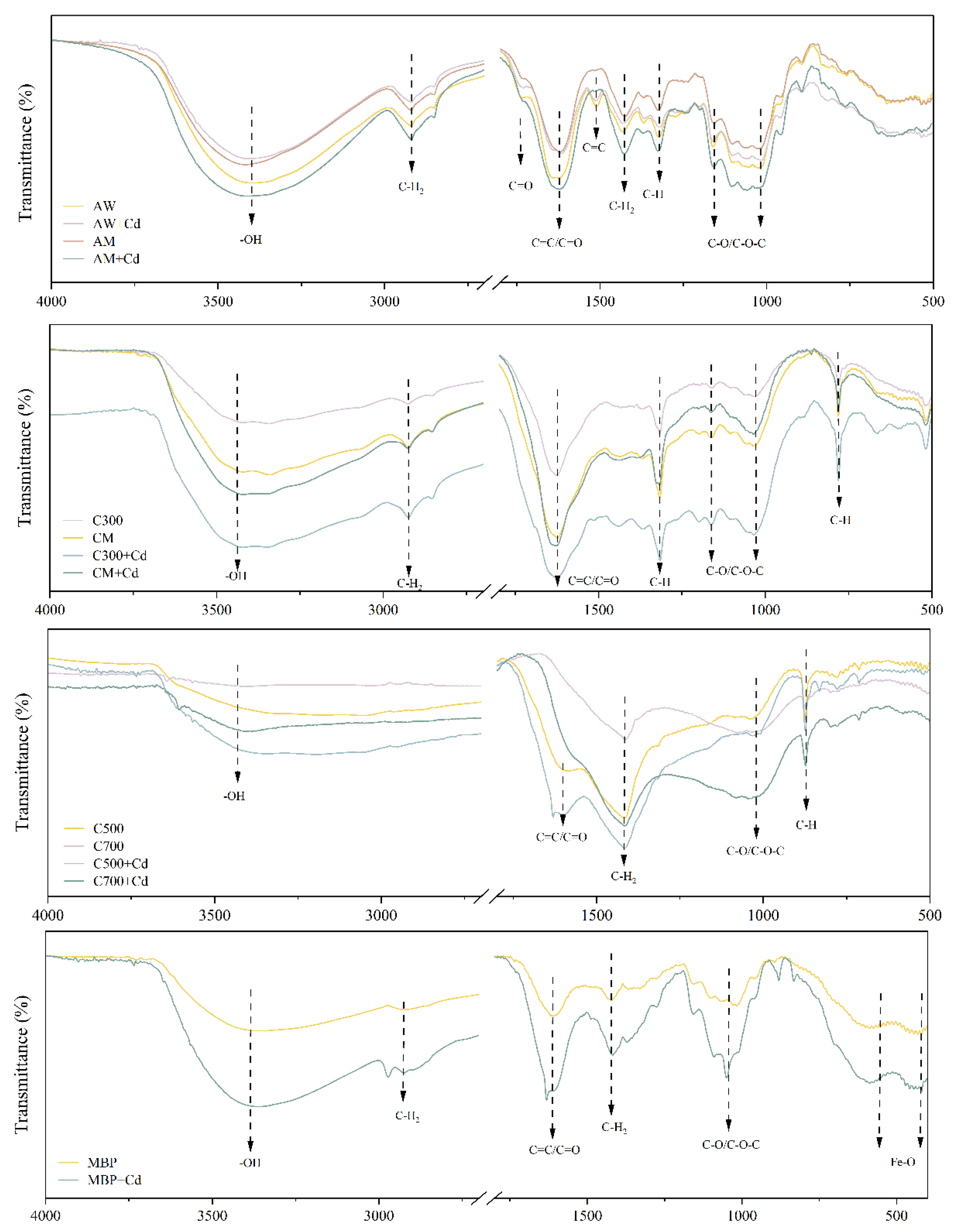

Figure 2 shows that the bio-adsorbents derived from Allium cepa var. aggregatum waste showed irregular lamellar and laminar structures with rough surfaces characterized by obvious wrinkles and corrugated structures. MBP showed excellent superparamagnetic behavior with a saturation magnetization intensity of 3.69 emu/g (Figure 3). MBP had ultra-paramagnetic characteristics, which helped it achieve the complete separation of the adsorbent-loaded Cd from the soil as well as enhanced Cd2+ removal. It can be learned from Figure 4 that AW was mainly composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, and was rich in phenols, alcohols, ketones, and aromatic rings. The bio-adsorbents derived from Allium cepa var. aggregatum waste were enriched with functional groups such as -OH and C=O, which provide the foundation for the adsorption of Cd2+ by complexation.

Figure 2.

Surface morphology of bio-adsorbents obtained from SEM.

Figure 3.

Hysteresis loop of MBP.

Figure 4.

FT-IR image of bio-adsorbents.

The basic physicochemical properties and Cd2+ removal capacity of bio-adsorbents are shown in Table 3. Bio-adsorbents derived from Allium cepa var. aggregatum waste belong to mesoporous materials that contain large amounts of oxygen-containing functional groups and display superior adsorption capacity of Cd2+ in solution. The specific surface area and pore volume of biochar increased with the increase of the cracking temperature. Cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in biomass completely decomposed when the cracking temperature exceeded 600 °C [14], and the specific surface area and pore volume of biochar increased rapidly, resulting in a high specific surface area of C700, which was as high as 66.0080 m2/g, which showed excellent adsorption capacity. At a dosage of 3.0 g/L, the removal rate of Cd2+ by adsorbents was as follows: C700 > MBP > C500 > CM > AM > AW > C300. The adsorption capacity of biochar on Cd2+ was gradually enhanced with the increase of the cracking temperature, and the adsorption performance of low-temperature biochar was significantly strengthened after modification by KMnO4 [17]. The adsorption efficiency of Cd2+ by bio-adsorbents was associated with the dosage of adsorbent, the concentration of Cd2+, and the action time, temperature, pH, ionic strength, and organic ligand concentration of the solution [29].

Table 3.

Properties and adsorption capacities of adsorbents.

3.2. Adsorption Mechanism of Cd2+ by Adsorbents

The detection of K+, Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ in the solution after adsorption proved the existence of an ion exchange mechanism (). These cations would be dissociated or dissolved from the original complexes on the adsorbent during adsorption due to changes in pH to form more stable Cd-containing precipitates or complexes. As a consequence of the low free energy required for the metal complexation process, a very stable complex or precipitate could be quickly formed on the surface of the adsorbent by Cd2+ exchanged with the metal cation [30]. Moreover, there was significantly more Ca2+ than K+ and Na+ injected into the solution. This was attributed to the fact that the bio-adsorbents contained much more Ca2+ than K+ and Na+.

As can be seen from Figure S2, there were many minerals like NaCl, KHCO3, and CaCO3 on the surface of the bio-adsorbents, which could directly co-precipitate with Cd2+. The fact that the diffraction peaks of KHCO3 and CaCO3 weakened and CdCO3 and CdCl2 appeared after adsorption indicated the existence of a mechanism of precipitation with minerals ().

It can be seen from the Figure 4 that the bio-adsorbents were rich in oxygen-containing functional groups such as -OH and the change in pH value before and after adsorption indicated that the coordinate complexation of oxygen-containing functional groups () and the release of hydrogen ions occurred during adsorption. It was observed that there were a large number of C=C, olefin C-H and benzene ring structures on the surface of the bio-adsorbents derived from Allium cepa var. aggregatum waste in addition to oxygen-containing functional groups, which can act as π-electron donors and play an important role during the adsorption of Cd2+ [31], and the changes in the vibrational peaks of benzene ring olefin after adsorption corroborated the existence of the Cd-π mechanism ().

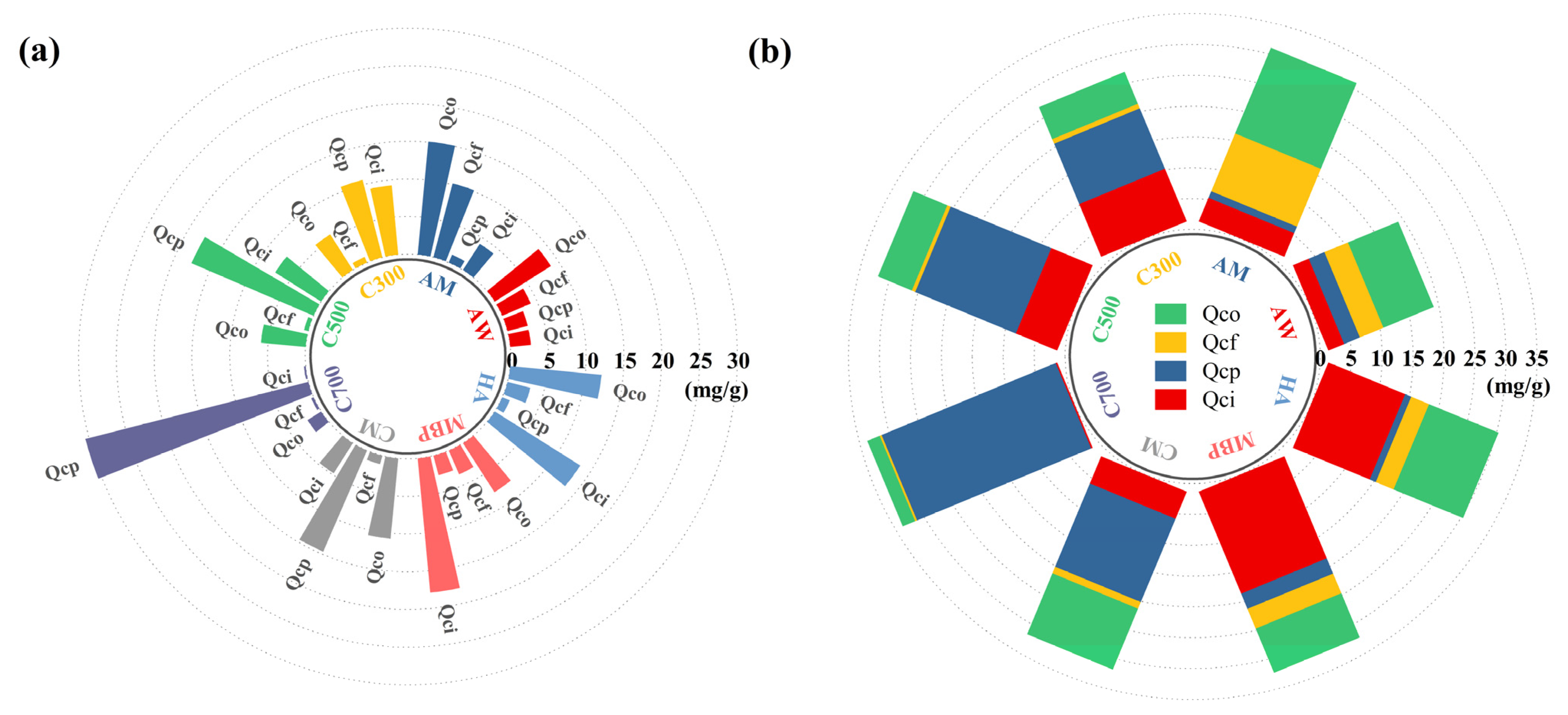

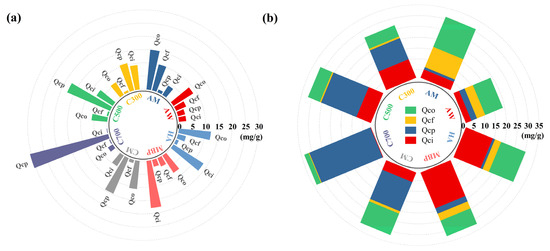

Overall, Figure 5 and Table S2 show that the adsorption of Cd2+ by AW and AM was mainly based on the Cd2+-π bonding and physical adsorption mechanism with contributions of 47.80% and 49.42%, respectively. AW was abundant in C=O/C=C, which acted as a donor of π-electrons [31]. The modification of NaOH decreased the adsorption capacity contributed by co-precipitation with minerals, but the introduction of -OH and cations led to an increase in the contribution of complexation with functional groups and in ion exchange, resulting in the promotion of adsorption. The injection of a large number of ions during the preparation of MBP provided an additional ion-exchange site, improving the Cd2+ capacity of ion-exchange to 56.29%, and the magnetism further enhanced the physical adsorption, thus improving the adsorption capacity.

Figure 5.

Adsorption mechanism of Cd2+ by adsorbents. (a) Adsorption capacity under different mechanisms; (b) percentage of adsorption under different mechanisms.

However, the adsorption of Cd2+ by biochar was mainly dominated by interaction with minerals. With the increase in the cracking temperature, the adsorption attributed to the ion-exchange mechanism was reduced from 9.23 mg/g in C300 to 0.22 mg/g in C700, while on the contrary, the adsorption by the precipitation with minerals was increased from 10.61 mg/g in C300 to 30.47 mg/g in C700, accounting for 91.75% of the Cd2+ adsorbed by C700. KMnO4 modification significantly enhanced the adsorption capacity of Cd2+ by unsaturated bonds and co-precipitation with minerals [17].

3.3. Removal of Cd from Soil Under Wet–Dry–Freeze Conditions

The adsorption capacity of Cd in soil by bio-adsorbents was affected by the properties of the soil. The pH of the black soil used in this experiment was 7.68, which belongs to alkaline soil, the ionic strength in the soil solution was relatively low, and the larger pH and lower EC were beneficial to the adsorption of Cd2+ by the bio-adsorbents. In addition, as shown in Table 1, there are many metal cations in the soil, which will compete with Cd2+ for the limited active sites on the surface of the adsorbent, thereby affecting Cd adsorption, resulting in a lower removal of Cd2+ from the soil by the bio-adsorbents than from the solution.

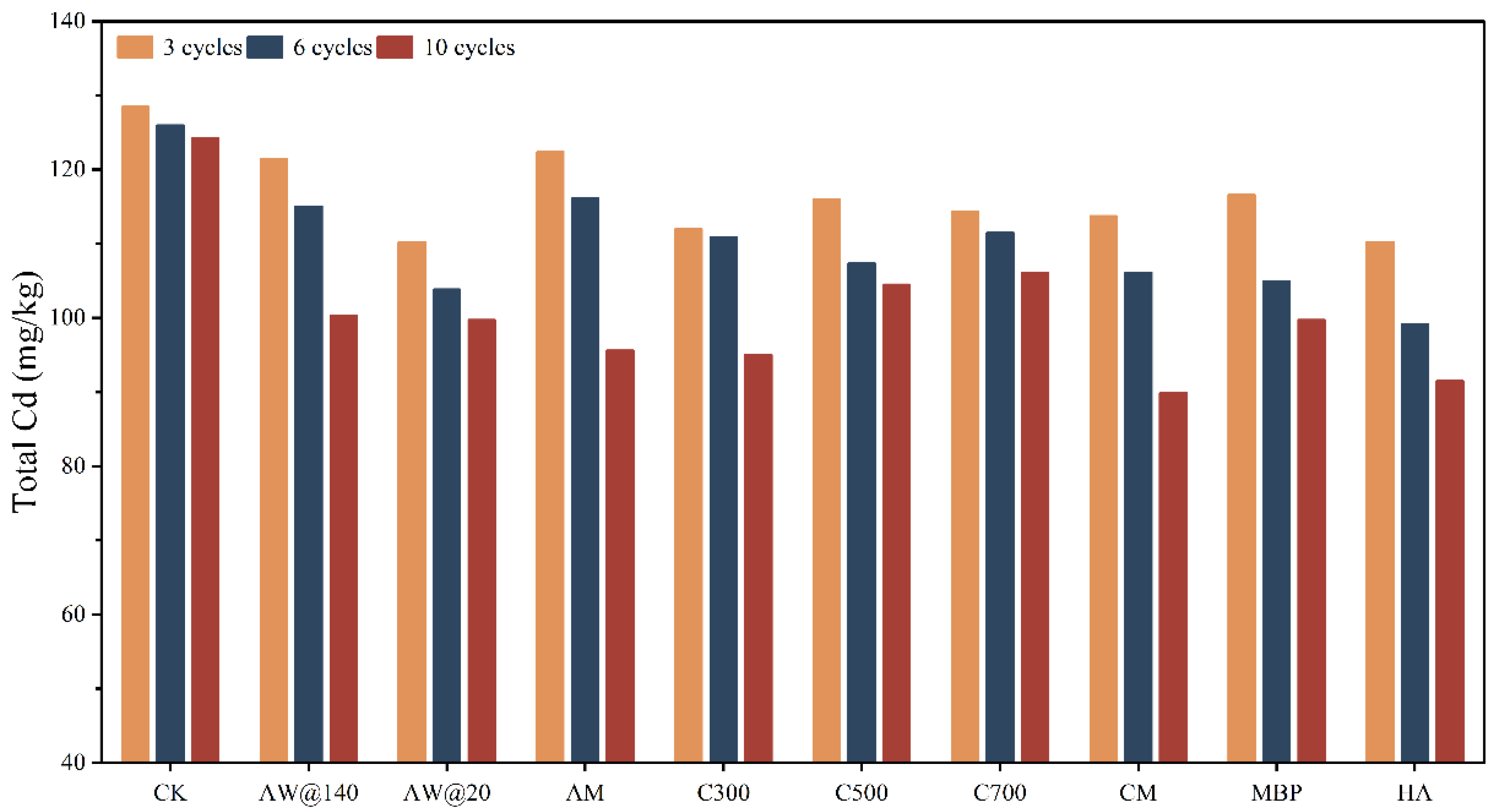

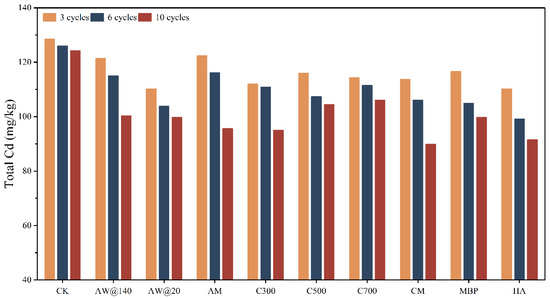

The soil was anthropogenically contaminated with a high percentage of Cd in strongly active forms like exchangeable fraction, and the changes in temperature and humidity and the movement of water during the freeze–thaw cycle contributed to the loss of Cd, which explains the decrease in the total and available Cd content in the control group with the extension of time. As can be seen from Figure 6, the removal of Cd from the soil became more significant as the frequency of the dry–wet–freeze cycles increased. At the end of the 10 cycles of remediation, there was almost no difference in the removal of total Cd and available Cd from soil by AW of different particle sizes, which was similar to the Cd removal behavior in solution, but a difference in the performance presented in the initial stage of remediation; at the end of the third and sixth cycles, the removal of the total Cd of AW@20 was 8.67% and 8.57% higher than AW@140, respectively. The performance of AM was relatively weak in the early stage of remediation, but at the end of the treatment, the removal of Cd by AM was improved by 3.66% in comparison to AW. The high efficiency of the large-particle size adsorbent realized the win–win situation of low cost and high profitability.

Figure 6.

Changes in total Cd content under dry–wet–thaw conditions.

The excellent adsorption properties of high-temperature biochar in solution were extremely restricted when applied in soil, where it lost its original structure, characteristics, and remediation capacity after being exposed to repeated dry–wet–freeze cycles together with the soil. This is consistent with the observation that the ability of biochar is not permanent for the direct immobilization of Cd in the soil, which decreases as it ages in the soil [32]. On the contrary, it was found that the low-temperature biochar, which was not ideal for Cd adsorption in solution, exhibited gradual superior remediation capacity in soil, outperforming AW at all the periods of remediation and eventually removing 26.81% of Cd in the soil. The adsorption performance of biochar was substantially improved after modification by KMnO4, with the removal rate being increased by 14.97% and 3.95% in water and soil, respectively.

It is worth pointing out that until the end of 10 cycles of remediation, the Cd loaded on the adsorbents only reached about one percent of the maximum adsorption capacity of the adsorbent, which was far from the full sorption capacity of the adsorbent, making it possible to remediate the contamination of Cd in the soil in a long-term and sustainable process with the advancement of time.

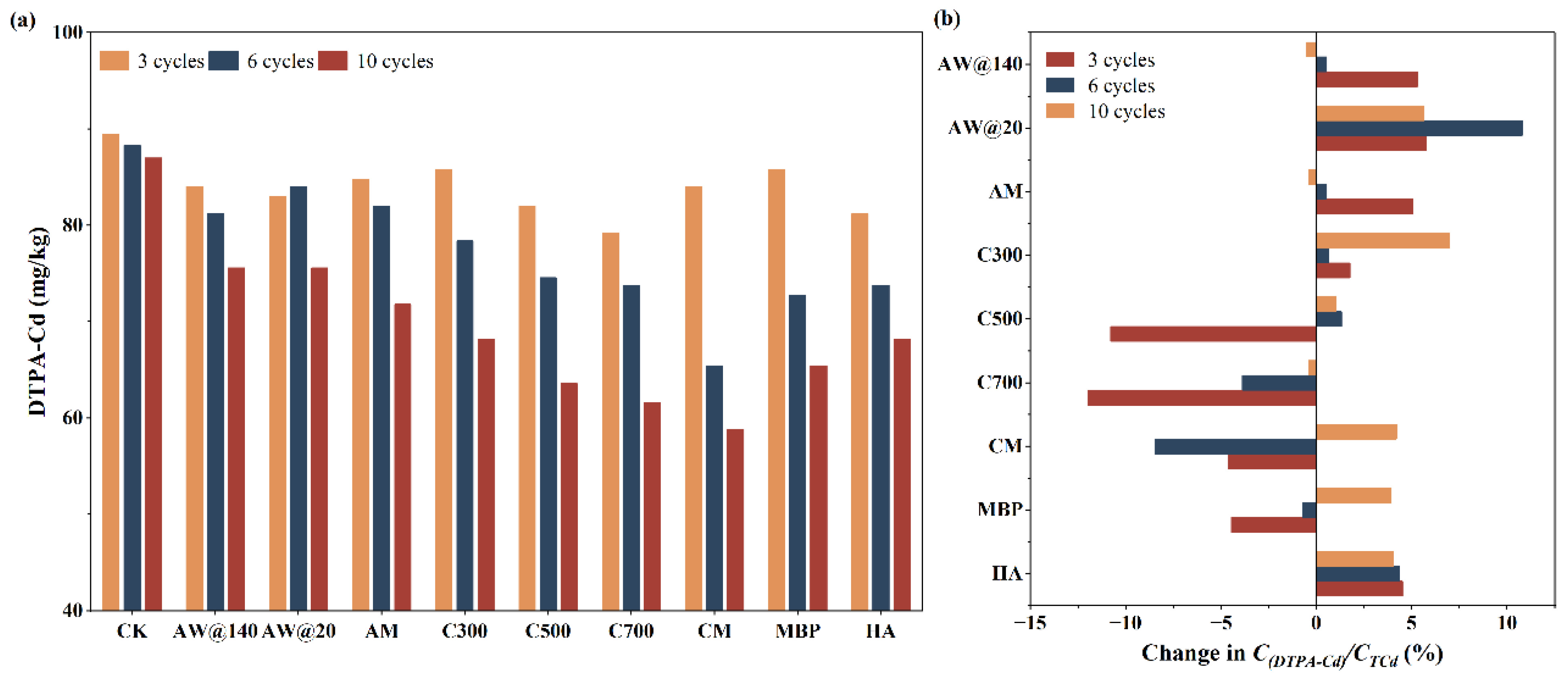

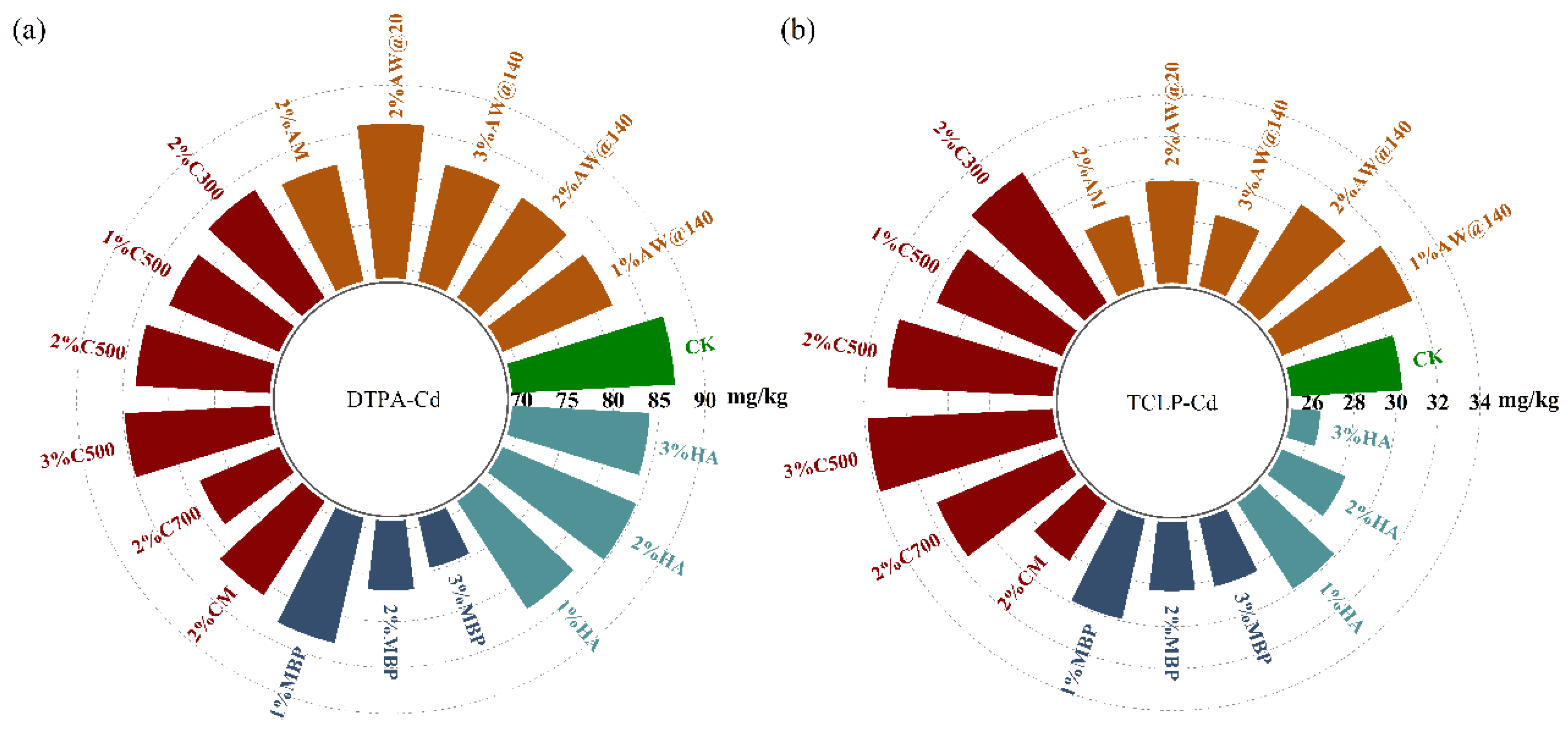

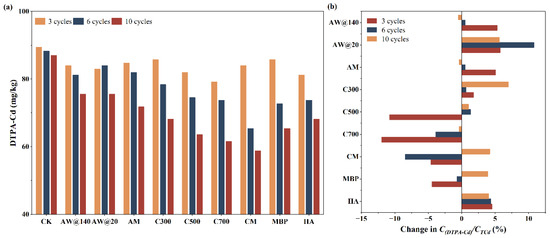

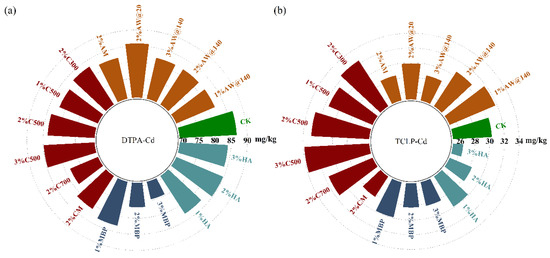

3.4. Immobilization of Cd Under Dry–Wet–Freeze Conditions

It is observed from Figure 7a that there was a gradual decrease in available Cd levels in soil in the treatment groups with different materials with the extension of treatment under dry–wet–freeze conditions, which was related to the adsorption and immobilization effects of the materials. Likewise, AW with different particle sizes presented the same efficiency in Cd adsorption and immobilization after remediation, while AW@20 performed superiorly during the preliminary stage of remediation. It was found that the removal and immobilization capacity of biochar was directly dependent on the cracking temperature, with a decrease in available Cd by 25.38% for C300 to 32.60% for C700. KMnO4 modification contributed to the removal and stabilization of available Cd by 35.67%, ranking CM first among the bio-adsorbents. The immobilization and removal of available Cd by MBP were primarily demonstrated in the middle and late stages of the remediation, which ultimately resulted in a 28.45% reduction in available Cd in the soil. HA acted steadily and consistently, with 25.38% of available Cd eliminated at the end of the treatment.

Figure 7.

Changes of available Cd in soil after dry–wet–freeze conditions. (a) Available Cd in soil; (b) changes of after dry–wet–freeze conditions.

Initially, available Cd accounted for 70.42% of the total Cd in the soil. Nevertheless, the inconsistency between the changes in the total and available Cd resulted in different degrees of changes in the proportion of available Cd at the end of dry–wet–freeze cycles, as shown in Figure 7b. An increase in soil was observed in the treatment groups of AW, AM, HA, and C300, while the opposite phenomenon was recognized in the treatment groups of C500 and C700. It was interesting to learn that decreased in the early stage but increased in the later stage of the remediation process for the treatment groups of MBP and CM, which indicated that AW, AM, and biochar cracking at a low temperature mainly manifested adsorption effect, while biochar obtained at medium and high temperatures mainly acted as an immobilization effect during the whole remediation process under dry–wet–freeze conditions. There were both relatively vigorous adsorption and immobilization of Cd in soil by CM and MBP, with adsorption dominating in the early stage and immobilization dominating in the later stage.

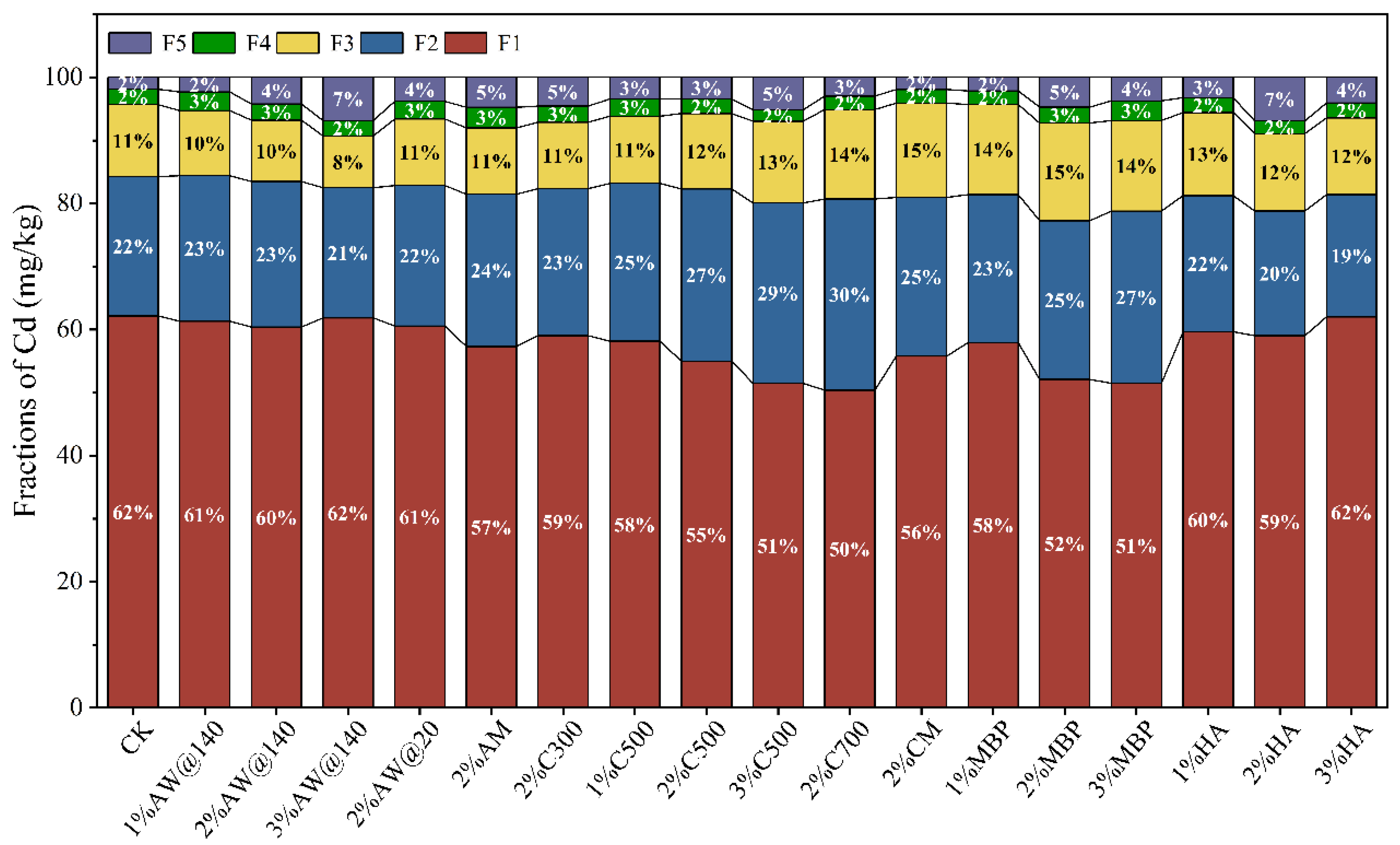

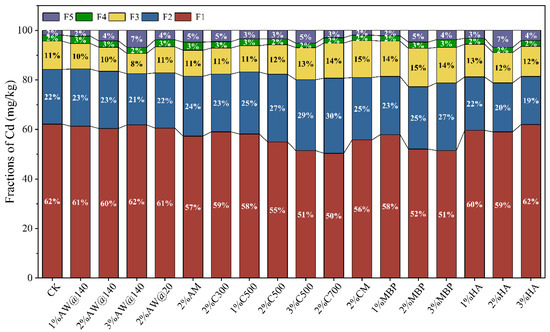

3.5. Fractions of Cd in Soil After Immobilization

The fractions of Cd were obviously changed after 45 days of immobilization and remediation in the different treatment groups. Cd primarily existed in active fractions in the contaminated soil, with the exchangeable fraction accounting for 62.17% of the total Cd, and the carbonate-bound and the Fe-Mn oxide-bound fractions accounting for 22.08% and 11.42% of the total Cd, respectively. As shown in Figure 8, a decrease in the exchangeable Cd content and an increase in the residual Cd content in the soil was observed in all treatment groups after 45 days of immobilization treatment. Consistently, AW across various particle sizes demonstrated equivalent efficacy in immobilizing Cd2+ in soil. With an increased application ratio of AW@140, there was a notable shift of Cd towards more stable fractions, which resulted in a decrease in the concentrations of the four primary fractions and a significant rise in the residual fraction by 5.91%. Additionally, modification with NaOH further enhanced the stabilization of Cd by promoting its conversion into a more stable fraction.

Figure 8.

Fractions of Cd in soil before after immobilization (F1—exchangeable fraction, F2—carbonate-bound fraction, F3—Fe-Mn oxide-bound fraction, F4—organic-bound fraction, F5—residual fraction).

The immobilization of exchangeable Cd by biochar gradually strengthened with the increase in the cracking temperature and feeding ratio, which might be mainly due to the fact that the pH value of the soil improved, which was caused by the biochar amendment. C700 addition caused a reduction of 18.96% in exchangeable Cd at a dosage of 2%, which prompted its transformation to more stable fractions of carbonate and Fe-Mn oxide-bound fractions. In the case of C500, the fixation of exchangeable Cd increased from 6.44 to 17.22% when the amount of addition grew from 1 to 3%. A meta-analysis concluded that the incorporation of biochar from Japanese cedar, Japanese cypress, poultry manure, and wastewater sludge resulted in a decrease in soil exchangeable Cd and a significant increase in Cd in carbonate-bound, Fe-Mn-bound, and organic matter-bound fractions, while the percentage of residue Cd did not clearly show change [33]. The application of CM further reduced exchangeable Cd in the soil and increased the proportion of carbonate-bound and Fe-Mn oxide-bound Cd based on C300, which correlated with a significant increase in enzyme activity and changes in the microbial structure and the abundance in the soil [34].

With an increase of the addition of MBP, there was a gradual decline of exchangeable Cd that transferred to stable fractions, leading to an increase in carbonate-bound Cd. The abundant amount of iron in MBP contributed to an increment in the percentage of Cd in the Fe-Mn oxide status. Likewise, a higher reduction of exchangeable Cd in the soil was observed in the MBP treatment group relative to the AW treatment group. As a consequence of HA treatment, a decline in Cd in the exchangeable and carbonate-bound fractions but an increase in the residue fraction were found, with the 2% addition of HA treatment exhibiting the most optimal immobilization effect on Cd and a significant change in Cd fractions.

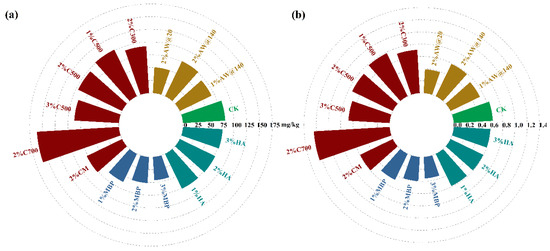

3.6. Change of Available Cd in the Soil After Immobilization

The DTPA and TCLP methods were both applied to obtain the available Cd content in contaminated soil at the same time. Correspondingly, DTPA-Cd contained portions of Cd that existed in exchangeable, carbonate-bound, and Fe-Mn oxide-bound fractions, whereas TCLP-Cd leached the acid-extractable status using CH3COOH. Different changing tendencies of the available Cd were demonstrated among the TCLP and DTPA methods.

It can be learned from Figure 9 and Table S3 that the DPTA-Cd content in the soil showed a decreasing trend after 45 days of treatment. The immobilization effect on DTPA-Cd was more remarkable with the increase in the MBP addition, but the increase in the ratio of AW@140 and HA addition caused no significant promotion of the immobilization procedure. Biochar treatments resulted in a decrease in the soil DTPA-Cd percent, which was mainly attributed to the immobilization of Cd on biochar particles and the effect of biochar on soil properties. In addition to direct interactions with biochar, changes in soil properties caused by biochar application also indirectly increase the ability of soil particles to absorb, immobilize, and precipitate Cd, thereby decreasing their bioavailability [35,36]. The modification of NaOH and KMnO4 enhanced the immobilization capacity of adsorbents for DTPA-Cd in soil.

Figure 9.

Change of available Cd after immobilization. (a) Available Cd extracted with DTPA method; (b) available Cd extracted with TCLP method.

However, biochar and 1% AW@140 treatment caused an increase in TCLP-Cd in the soil. Particularly, the more significant increase in TCLP-Cd was observed with the increase in the ratio of C500 application, which might be attributed to the fact that the biochar altered the structural properties of the soil to a large extent, resulting in the release of acid-extractable Cd. However, the modification of KMnO4 successfully solved the problem of soil Cd activation due to biochar application and reduced the proportion of TCLP-Cd considerably.

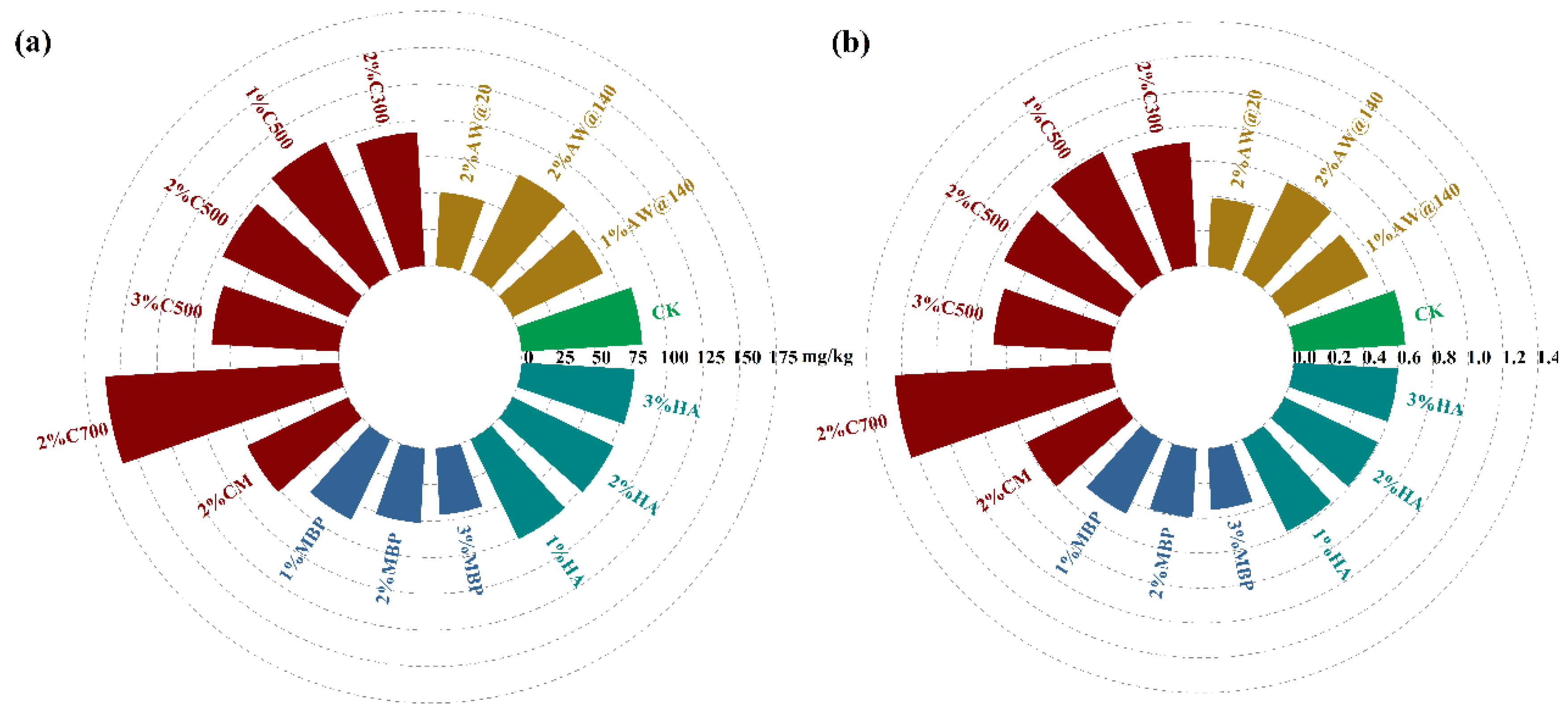

3.7. Cd Uptake from Soil by Plants After Remediation

Calcium stress under cadmium-contaminated conditions disrupts photosynthetic efficiency, nutrient uptake, and biomass production, and thus reduces crop yields [37]. The effects of biomaterial application on plants were mainly reflected as the promotion and inhibition of their biomass growth and nutrient element or Cd uptake. The effect of plant growth was specifically reflected in the promotion of plant growth by biochar and HA, and its inhibition by AW and AM. The high nutrient content in AW, biochar, and HA effectively promoted the uptake and utilization of nutrients and Cd in the soil by the plants.

Cd concentration in the aboveground part of Brassica juncea reduced after the application of AW, CM, MBP, and HA. At the same application rate, the reduction in Cd concentration in the edible part of the plant was as follows: AW@20 > MBP > AW@140 > CM > HA. Among them, MBP showed the best and most stable effectiveness in immobilizing the bioavailable Cd in the soil. In addition, the Cd uptake by the edible part of the plant showed a significant decreasing trend with the increase in MBP application, leading to a 45.05% decrease in plant Cd concentration after the treatment of 3% MBP. The natural adsorbent with a large particle size displayed the best Cd immobilization efficiency, with a 39.27% reduction in the concentration of Cd taken up by the plant after treatment with 2% AW@20, ranked 1.97 times that of AW@140. However, with the increase in the dosage of AW, while the growth of plants was inhibited, Cd accumulated in the cells and tissues of the plants with limited biomass, leading to the growth of the Cd concentration. The immobilization efficiency of AW@20 on Cd in soil was certainly outstanding, but its addition seriously restricted the growth of plants. Furthermore, the addition of AM had a large impact on the soil composition and properties, causing salinization of the soil performance, which possibly caused a significant decrease in crop yield during practical application.

Similarly, HA encouraged the growth of plants while promoting their uptake of nutrients and Cd; with the increase in the proportion of HA, the growth and uptake were simultaneously enhanced, leading to a significant feedback in which the high use of HA did not lead to a decrease in the uptake of Cd in the plant. The importance of HA in black soil in immobilizing Cd in the soil and reducing the edible Cd concentration in plants can be recognized.

Biochar derived from agricultural waste is known to improve soil pH, enhance the soil structure, and promote water and nutrient retention, microbial growth, and plant nutrient uptake by altering the soil hardness, porosity, and cation exchange capacity [38,39]. Furthermore, biochar application was also capable of significantly improving the availability of soil nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, providing nutrient efficiency, accelerating microbial acquisition, and boosting plant biomass [40]. It can be concluded from Figure 10 and Table S4 that biochar treatment boosted the growth of plants but there was a general increase in Cd uptake by plants; moreover, Cd uptake by plants increased with cracking temperature (Figure 10). This was attributed to several reasons: (1) the application of biochar reduced the soil Cd stress and improved the physical and biological properties of soil; (2) the nutrient-rich biochar promoted the growth and uptake of plants; (3) the effect of the increase in the TCLP-Cd percent in the soil resulted in a greater uptake of Cd by plants [34]. The 93.72% increase in Cd uptake by plants after C700 treatment was attributed to the lower content of oxygenated functional groups on the surface of the high-temperature biochar (>600 °C), which led to the formation of insoluble minerals such as crandallite and wavellite, resulting in a reduced phosphorus availability [41,42], resulting in turn in a worse response to the Cd concentration in both the ground part and root system of plants [43]. Cd concentration in the edible part of Brassica juncea decreased with the increase in C500 application, which was attributed to the dilution effect of Cd by the larger biomass of the plant after the high percentage of biochar significantly promoted its growth [44]. However, after modification with KMnO4, CM was able to effectively reduce the amount of available Cd in soil, significantly lowering the concentration of Cd in the edible part of the plant compared to C300.

Figure 10.

Cd uptake by plants in different treatment groups. (a) Cd Concentration in plants; (b) BCF of plants.

3.8. Biochar in Conjunction with Hyperaccumulators Remediation

Generally, hyperaccumulators of Cd were mainly characterized by Compositae and Cruciferae [45,46]. However, these hyperaccumulators were normally found in the vicinity of mining areas, and most of them were wild species with a slow growth rate, low biomass, and long remediation time, leading to greater uncertainties and difficulties in the remediation process. Therefore, screening or cultivating controllable native species as Cd hyperaccumulators can effectively improve the phytoremediation efficiency and reduce the environmental risk. The Brassica juncea employed in this research belongs to Cruciferae-Brassica but is not a hyperaccumulator [47]. Researchers indicated that Fulu No.1, 94-N1, Japanese Huaguan, Japanese Dongfei, Hongqiaoaiqing of B. chirensis and Ducati, Matsumo, Gideon, Invinto of B.·oleracea are the potential materials for phytoremediating Cd pollutants in soil with a BCF up to 65.56–146.85 [48].

Therefore, it was proposed in this research to combine the use of biochar derived from Allium cepa var. aggregatum waste, and especially biochar cracking at a high temperature with a Brassica hyperaccumulator of Cd, to enhance the phytoremediation efficiency. Under the circumstances of greenhouse covering, pest control, and scientific fertilization, about 7–8 up to 11 batches of plants could be harvested as well as a yield of 1000–1750 kg/acre could be achieved. Biochar derived from Allium cepa var. aggregatum waste application significantly promotes the growth of plants as well as the uptake of Cd from the soil, achieving a rapid and efficient removal of Cd from contaminated soil.

4. Conclusions

Bio-adsorbents derived from Allium cepa var. aggregatum waste showed superior adsorption performance for Cd2+ with the main mechanisms of adsorption, including ion exchange, co-precipitation with minerals, functional group complexation, Cd2+-π bonding, and physical adsorption mechanism. Bio-adsorbents exhibited excellent adsorption and immobilization of Cd in black soils. The addition of bio-adsorbents promoted the transformation of Cd from exchangeable to more stable fractions and reduced the Cd bioavailability under characteristic wet–dry–freeze conditions experienced by black soil in northeast China. The application of AW, CM, and MBP reduced the available Cd content of soil and restricted Cd uptake by plants. However, the application of biochar in a short period increased the soil TCLP-Cd content and promoted more Cd uptake by plants, which could be applied in combination with hyperaccumulators to efficiently remove Cd from the soil in a short period of time. The humus abundant in black soil provided adsorption and immobilization of Cd, contributing to the defense against Cd contamination in black soil. However, this research focused on the Cd remediation of black soil by bio-adsorbents derived from Allium cepa var. aggregatum waste in northeast China. Nevertheless, multiplier onions are cultivated in many countries around the world, and the remediation performances of different varieties of onion wastes on potentially toxic elements in different types of soils could be explored in future studies to comprehensively reveal the environmental benefits of the application of onion wastes. In addition, the combined use of biochar from multiplier onion waste and hyperaccumulators for the remediation of Cd-contaminated soil should be deeply investigated further.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15040427/s1; Figure S1: Methodology and procedures of this research; Figure S2: XRD diffraction spectra before and after adsorption; Table S1: Temperature setting procedure of graphite digestion instrument; Table S2: Adsorption mechanism of Cd by bio-adsorbents (mg/g); Table S3: Immobilization of available Cd by bio-adsorbents in soil (mg/kg); Table S4: Cd uptake by plants after bio-adsorbents application [27,49,50].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H.; methodology, Y.H.; validation, J.L., Y.L. and Q.W.; formal analysis, Y.H. and Y.L.; investigation, Y.H. and Z.G.; resources, Q.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, J.L. and X.Z.; visualization, Y.H.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the State Key Research and Development Program (2023YFC2907105) and the Special study on mineral resources planning in Changchun (JM-2020-11-13594).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agarry, S.E.; Ogunleye, O.O.; Ajani, O.A. Biosorptive Removal of Cadmium(II) Ions from Aqueous Solution by Chemically Modified Onion Skin: Batch Equilibrium, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2015, 202, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.C.V.; da Costa, A.C.A.; Henriques, C.A.; Luna, A.S. Kinetic modeling and equilibrium studies during cadmium biosorption by dead Sargassum sp biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 91, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, F.; Zheng, W.W. Cadmium Exposure: Mechanisms and Pathways of Toxicity and Implications for Human Health. Toxics 2024, 12, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Assessment of Soil Pollution; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.Y.; Zhang, G.L.; Xie, Y.; Shen, B.; Gu, Z.J.; Ding, Y.Y. Delineating the black soil region and typical black soil region of northeastern China. Chin. Sci. Bull.-Chin. 2021, 66, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.Y. Impacts of land use and soil conservation measures on runoff and soil loss from two contrasted soils in the black soil region, northeastern China. Hydrol. Process. 2023, 37, e14886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.L.; Meng, D.; Li, X.J.; Zhu, F. Soil degradation and food security coupled with global climate change in northeastern China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 23, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.J.; Xie, Y.; Gao, Y.; Ren, X.Y.; Cheng, C.C.; Wang, S.C. Quantitative assessment of soil productivity and predicted impacts of water erosion in the black soil region of northeastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 637, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Y.; Deng, B.L.; Wu, M.X.; Qiu, G.K.; Sun, Z.H.; Wang, T.Y.; Zhang, S.Q.; Yang, X.T.; Song, N.N.; Zeng, Y.; et al. Impacts of natural field freeze-thaw process on the release kinetics of cadmium in black soil: Soil aggregate turnover perspective. Geoderma 2024, 447, 116932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Q.H.; Huang, D.Y.; Zhu, H.H.; Xu, C.; Su, S.M.; Zeng, X.B. Influence of straw-derived humic acid-like substance on the availability of Cd/As in paddy soil and their accumulation in rice grain. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.R.; Ren, J.; Tao, L.; Ren, X.C.; Li, Y.M.; Jiang, Y.C.; Lv, M.R. Potential of Attapulgite/Humic Acid Composites for Remediation of Cd-Contaminated Soil. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.H.; Ma, J.C.; Xu, M.; Li, X.; Tao, J.H.; Wang, G.Z.; Yu, J.T.; Guo, P. The Adsorption and Desorption of Pb2+ and Cd2+ in Freeze-Thaw Treated Soils. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 96, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.L.; Du, W.; Wang, L.P.; Cao, Y.; Lv, J.L. Effects of freeze-thaw leaching on physicochemical properties and cadmium transformation in cadmium contaminated soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 284, 116935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Wabel, M.I.; Al-Omran, A.; El-Naggar, A.H.; Nadeem, M.; Usman, A.R.A. Pyrolysis temperature induced changes in characteristics and chemical composition of biochar produced from conocarpus wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 131, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battocchi, D.; Simões, A.M.; Tallman, D.E.; Bierwagen, G.P. Electrochemical behaviour of a Mg-rich primer in the protection of Al alloys. Corros. Sci. 2006, 48, 1292–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, L.; Wang, C.-Q.; Zhang, Q.-P.; Liu, Q.-C.; Li, Y.-D.; Xiao, R. Adsorption of Cd(II) from aqueous solutions by rape straw biochar derived from different modification processes. Chemosphere 2017, 175, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Huang, S.; Lin, Z. Effects of modification and co-aging with soils on Cd(II) adsorption behaviors and quantitative mechanisms by biochar. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 8902–8915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Liu, X.; Huang, G.; Xiao, W.; Han, L. The composition characteristics of different crop straw types and their multivariate analysis and comparison. Waste Manag. 2020, 110, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.J.; Liu, L.P.; Li, F.; Tang, Y.X.; Ge, F.; Tian, J.; Zhang, M. A hypoxic pyrolysis process to turn petrochemical sludge into magnetic biochar for cadmium-polluted soil remediation. J. Cent. South Univ. 2024, 31, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ke, S.J.; Xia, M.W.; Bi, X.T.; Shao, J.A.; Zhang, S.H.; Chen, H.P. Effects of phosphorous precursors and speciation on reducing bioavailability of heavy metal in paddy soil by engineered biochars. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 285, 117459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.T.; Li, W.D.; Jiang, M.H.; Wang, J.A.; Shi, X.Y.; Song, J.H.; Zhang, W.X.; Wang, H.J.; Cui, J. Improving the ability of straw biochar to remediate Cd contaminated soil: KOH enhanced the modification of K3PO4 and urea on biochar. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 262, 115317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shao, J.C.; Shen, L.P.; Xiu, J.H.; Shan, S.D.; Ma, K.T. Pretreatment of straw using filamentous fungi improves the remediation effect of straw biochar on bivalent cadmium contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 60933–60944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Xiao, J.G.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, W. Effects of magnetic hydroxyapatite loaded biochar on Cd removal and passivation in paddy soil and its accumulation in rice: A 2-year field study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 9865–9873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, U.B. 30—Potato onion (Multiplier onion). In Handbook of Herbs and Spices; Peter, K.V., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 495–501. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Liu, G.C.; Zheng, H.; Li, F.M.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.S.; Liu, C.; Chen, L.; Xing, B.S. Investigating the mechanisms of biochar’s removal of lead from solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 177, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.Q.; Fang, S.Y.; Yao, Y.Q.; Li, T.Q.; Ni, Q.J.; Yang, X.E.; He, Z.L. Potential mechanisms of cadmium removal from aqueous solution by Canna indica derived biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 562, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.W.; Huang, S.; Xu, T.; Deng, Y.Y.; Lin, Z.B.; Wang, X.G. Transport and transformation of Cd between biochar and soil under combined dry-wet and freeze-thaw aging. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, A.; Campbell, P.G.C.; Bisson, M. Sequential extraction procedure for the speciation of particulate trace metals. Anal. Chem. 1979, 51, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Duvnjak, Z. Adsorption kinetics of cupric and cadmium ions on corncob particles. Process. Biochem. 2005, 40, 3446–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Qiu, R. Relative distribution of Pb2+ sorption mechanisms by sludge-derived biochar. Water Res. 2012, 46, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, O.R.; Herbert, B.E.; Rhue, R.D.; Kuo, L.J. Metal Interactions at the Biochar-Water Interface: Energetics and Structure-Sorption Relationships Elucidated by Flow Adsorption Microcalorimetry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 5550–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.H.; He, J.Y.; Chen, Q.; He, F.; Wei, T.; Jia, H.L.; Guo, J.K. Marked changes in biochar’s ability to directly immobilize Cd in soil with aging: Implication for biochar remediation of Cd-contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 73856–73864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameyama, K.; Miyamoto, T.; Iwata, Y. Comparison of plant Cd accumulation from a Cd-contaminated soil amended with biochar produced from various feedstocks. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 12699–12706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Wang, Y.L.; Wang, L.E.; Huang, H.J.; Zhou, C.H.; Ni, G.R. Reduced cadmium(Cd) accumulation in lettuce plants by applying KMnO4 modified water hyacinth biochar. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beesley, L.; Moreno-Jiménez, E.; Gomez-Eyles, J.L.; Harris, E.; Robinson, B.; Sizmur, T. A review of biochars’ potential role in the remediation, revegetation and restoration of contaminated soils. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 3269–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Qayyum, M.F.; Ibrahim, M.; Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Abbas, T.; Ok, Y.S. Mechanisms of biochar-mediated alleviation of toxicity of trace elements in plants: A critical review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 2230–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, A.; Herdean, A.; Schmidt, S.B.; Sharma, A.; Spetea, C.; Pribil, M.; Husted, S. The Impacts of Phosphorus Deficiency on the Photosynthetic Electron Transport Chain. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.; Ali, S.; Ilyas, M.; Riaz, M.; Akhtar, K.; Ali, K.; Adnan, M.; Fahad, S.; Khan, I.; Shah, S.H.; et al. Enhancing phosphorus availability, soil organic carbon, maize productivity and farm profitability through biochar and organic-inorganic fertilizers in an irrigated maize agroecosystem under semi-arid climate. Soil Use Manag. 2021, 37, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Kim, K.H.; Kwon, E.E. Biochar as a tool for the improvement of soil and environment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1324533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jing, Y.; Chen, C.; Xiang, Y.; Rezaei Rashti, M.; Li, Y.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, R. Effects of biochar application on soil nitrogen transformation, microbial functional genes, enzyme activity, and plant nitrogen uptake: A meta-analysis of field studies. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 1859–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, H.; Sun, J. Pyrolysis temperature affects phosphorus transformation in biochar: Chemical fractionation and 31P NMR analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 569–570, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, M.; Ahmad, W.; Hussain, F.; Ahamd, W.; Numan, M.; Shah, M.; Ahmad, I. Phytostabalization of the heavy metals in the soil with biochar applications, the impact on chlorophyll, carotene, soil fertility and tomato crop yield. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, H.A.; Li, X.; Jeyakumar, P.; Wei, L.; Huang, L.X.; Huang, Q.; Kamran, M.; Shaheen, S.M.; Hou, D.Y.; Rinklebe, J.; et al. Influence of biochar and soil properties on soil and plant tissue concentrations of Cd and Pb: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Liu, X.Y.; Bian, R.J.; Cheng, K.; Zhang, X.H.; Zheng, J.F.; Joseph, S.; Crowley, D.; Pan, G.X.; Li, L.Q. Effects of biochar on availability and plant uptake of heavy metals—A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 222, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gierón, Z.Z.; Sitko, K.; Zieleznik-Rusinowska, P.; Szopinski, M.; Rojek-Jelonek, M.; Rostanski, A.; Rudnicka, M.; Malkowski, E. Ecophysiology of Arabidopsis arenosa, a new hyperaccumulator of Cd and Zn. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.H.; Zhou, Q.X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, K.S.; Guo, G.L.; Ma, Q.Y.L. A newly-discovered Cd-hyperaccumulator Solanum nigrum L. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2005, 50, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.J.M.; Brooks, R.R.; Pease, A.J.; Malaisse, F. Studies on copper and cobalt tolerance in three closely related taxa within the genus Silene L. (Caryophyllaceae) from Zaïre. Plant Soil 1983, 73, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.L.; Zheng, J.G. Cd-accumulation characteristics of Brassica cultivars and their potential for phytoremediating Cd-contaminated soils. J. Fujian Agric. For. Univ. 2004, 33, 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi, S.; Aller, D.M.; Laird, D.A.; Chintala, R. Comparison of the Physical and Chemical Properties of Laboratory- and Field-Aged Biochars. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 1627–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spokas, K.A. Impact of biochar field aging on laboratory greenhouse gas production potentials. GCB Bioenergy 2013, 5, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).