Effect of Kaolin Clay on Post-Bloom Thinning Efficacy, Cropping, and Fruit Quality in ‘Gala Vill’ Apple (Malus × domestica) Cultivation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

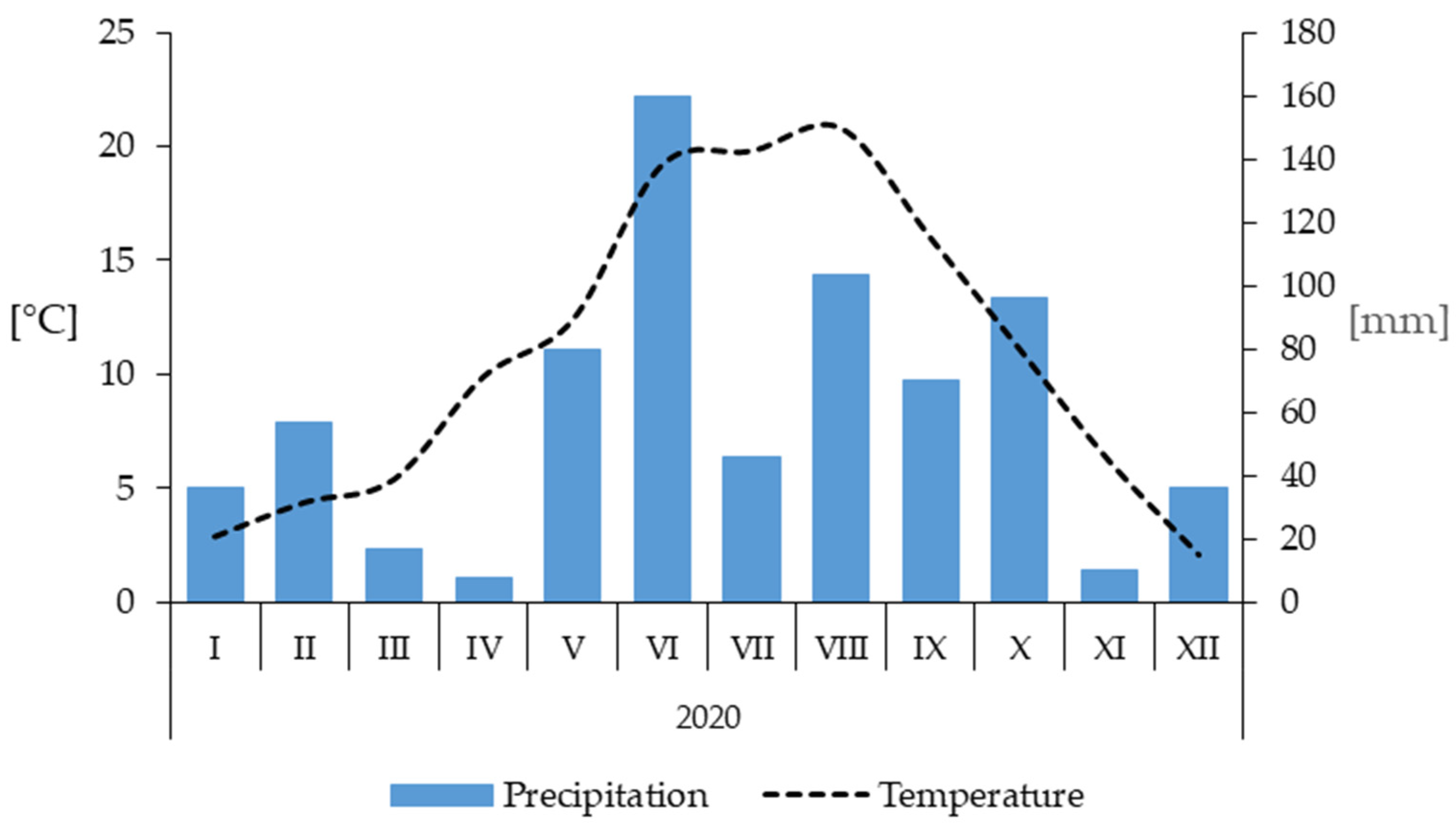

2.1. Location, Plant Material, and Experimental Design

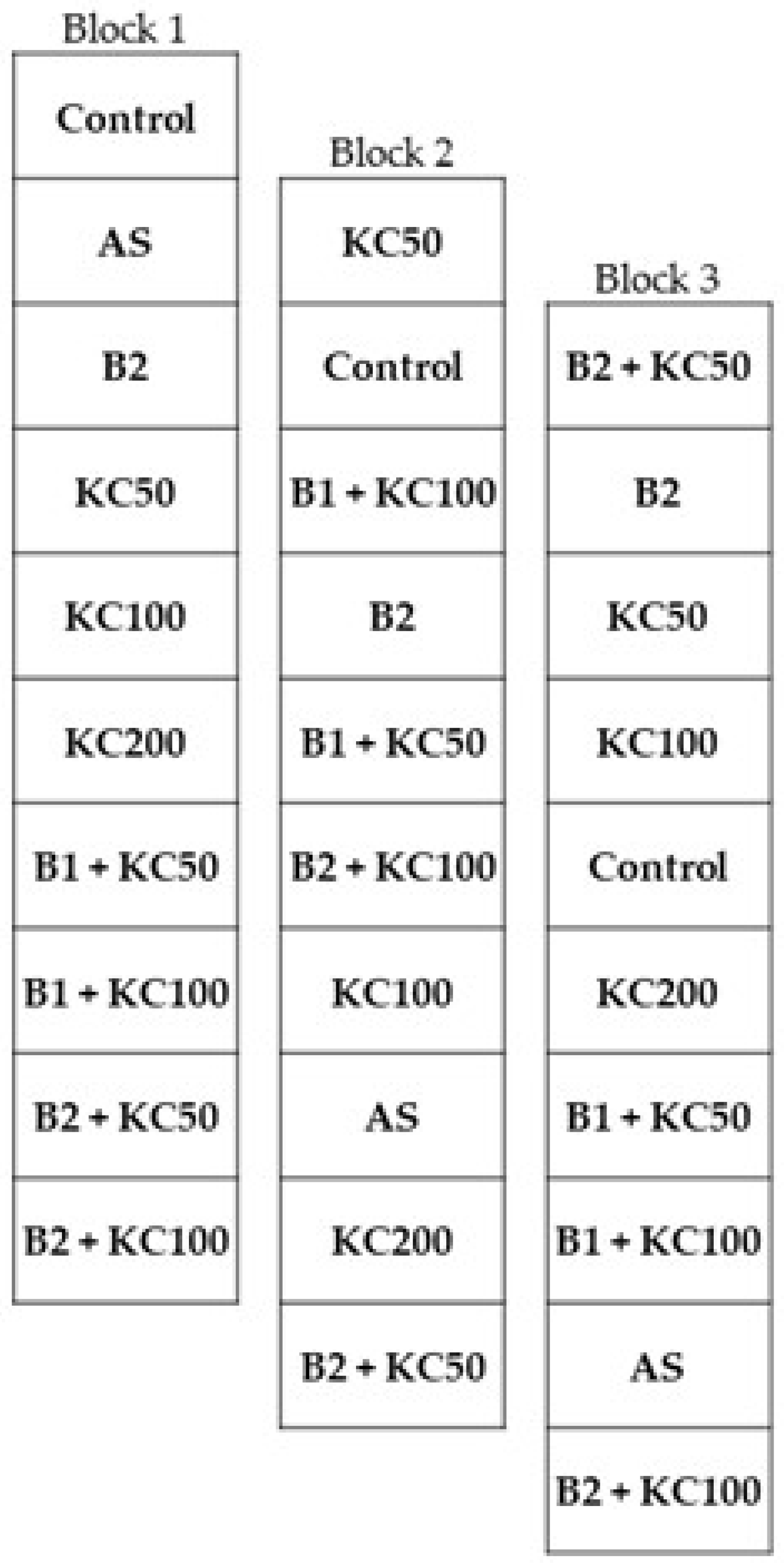

- (1)

- The control (control), where no thinning treatments were applied;

- (2)

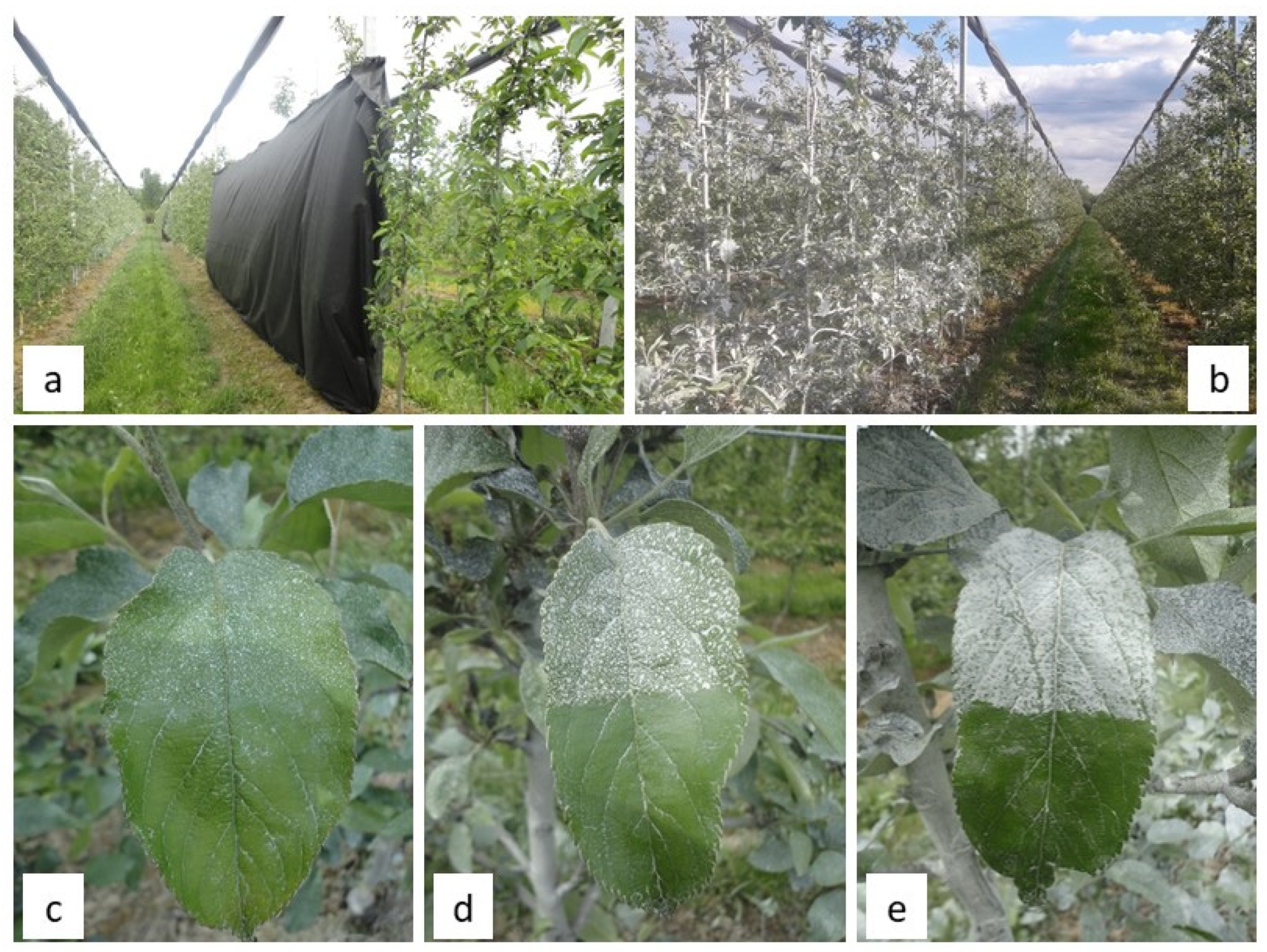

- Artificial shading (AS), where a black agro-textile (density: 50 g∙m−2), commonly used for mulching the soil to avoid weed competition, was applied over the trees for 5 days at a 6–8 mm fruitlet size (Figure 2a);

- (3)

- Brevis 2.2 (B2), where single applications of Brevis (containing metamitron as an active ingredient) at a dose of 2.2 kg∙ha−1 were applied at a 6–8 mm fruitlet size;

- (4)

- Kaolin Clay 50 (KC50), where a single application of kaolin clay was applied at a 50 kg∙ha−1 dose at a 6–8 mm fruitlet size (Figure 2b,c);

- (5)

- Kaolin Clay 100 (KC100), where a single application of kaolin clay was applied at a 100 kg∙ha−1 dose at a 6–8 mm fruitlet size (Figure 2d);

- (6)

- Kaolin Clay 200 (KC200), where a single application of kaolin clay was applied at a 200 kg∙ha−1 dose at a 6–8 mm fruitlet size (Figure 2e);

- (7)

- Brevis 1.1 + Kaolin Clay 50 (B1 + KC50), where a single application of Brevis at a 1.1 kg∙ha−1 dose was applied, followed by kaolin clay application at a 50 kg∙ha−1 dose at a 6–8 mm fruitlet size;

- (8)

- Brevis 1.1 + Kaolin Clay 100 (B1 + KC100), where a single application of Brevis at a 1.1 kg∙ha−1 dose was applied, followed by kaolin clay application at a 100 kg∙ha−1 dose at a 6–8 mm fruitlet size;

- (9)

- Brevis 2.2 + Kaolin Clay 50 (B2 + KC50), where a single application of Brevis at a 2.2 kg∙ha−1 dose was applied, followed by kaolin clay application at a 50 kg∙ha−1 dose at a 6–8 mm fruitlet size;

- (10)

- Brevis 2.2 + Kaolin Clay 100 (B2 + KC100), where a single application of Brevis at a 2.2 kg∙ha−1 dose was applied, followed by kaolin clay application at a 100 kg∙ha−1 dose at a 6–8 mm fruitlet size.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

2.2.1. Flowering, Fruit Setting, and Yield

2.2.2. Physiological Status and Inner and Outer Fruit Quality Determined Directly After Harvest

2.3. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Netsawang, P.; Damerow, L.; Lammers, P.S.; Kunz, A.; Blanke, M. Alternative Approaches to Chemical Thinning for Regulating Crop Load and Alternate Bearing in Apple. Agronomy 2023, 13, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bound, S.A. Determination of Target Crop Loads for Maximising Fruit Quality and Return Bloom in Several Apple Cultivars. Appl. Biosci. 2023, 2, 586–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peifer, L.; Ottnad, S.; Kunz, A.; Damerow, L.; Blanke, M. Effect of Non-Chemical Crop Load Regulation on Apple Fruit Quality, Assessed by the DA-Meter. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 233, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurlus, R.; Rutkowski, K.; Łysiak, G.P. Improving of Cherry Fruit Quality and Bearing Regularity by Chemical Thinning with Fertilizer. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, R.S.; Bound, S.A.; Hunt, I. Crop Load and Thinning Methods Impact Yield, Nutrient Content, Fruit Quality, and Physiological Disorders in ‘Scilate’ Apples. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, N.M.; Song, Y.-Y.; Nam, J.-C.; Yoo, J.; Kang, I.-K.; Cho, Y.S.; Yang, S.-J.; Park, J. Influence of Mechanical Flower Thinning on Fruit Set and Quality of ‘Arisoo’ and ‘Fuji’ Apples. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2023, 14, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yan, J.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Guan, Q.; Ma, F.; Zhang, J.; et al. Evaluating the Sustainable Cultivation of ‘Fuji’ Apples: Suitable Crop Load and the Impact of Chemical Thinning Agents on Fruit Quality and Transcription. Fruit Res. 2024, 4, e0024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, K.; Łysiak, G.P. Thinning Methods to Regulate Sweet Cherry Crops—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radivojevic, D.; Oparnica, C.; Milivojevic, J. Modeling of Apple Chemical Fruit Thinning. Ann. Univ. Craiova Agric. Mont. Cadast. Ser. 2023, 53, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.; Torres, E.; Àvila, G.; Bonany, J.; Alegre, S.; Carbó, J.; Martín, B.; Recasens, I.; Asin, L. Evaluation of Chemical Fruit Thinning Efficiency Using Brevis® (Metamitron) on Apple Trees (‘Gala’) under Spanish Conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 261, 109003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Nieto, L.; Ottnad, S.; Kunz, A.; Damerow, L.; Blanke, M. Metamitron Thinning Efficacy of Apple Fruitlets Is Affected by Different Rates, Timings, and Weather Factors in New York State. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kon, T.M.; Schupp, J.R.; Yoder, K.S.; Combs, L.D.; Schupp, M.A. Comparison of Chemical Blossom Thinners Using ‘Golden Delicious’ and ‘Gala’ Pollen Tube Growth Models as Timing Aids. HortScience 2018, 53, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ross Marchioretto, L.; De Rossi, A.; Michelon, M.F.; Orlandi, J.C.; Amaral, L.O.D. Ammonium Thiosulfate as Blossom Thinner in ‘Maxi Gala’ Apple Trees. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2018, 53, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaçal, E.; Öztürk, G.; Gür, İ.; Aydınlı, M.; Koçal, H.; Altındal, M.; Yıldırım, A.N. Crop Load Management with Blossom Thinners in ‘Redchief’ Apple and Their Effects on Fruit Mineral Composition. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2019, 61, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szot, I.; Basak, A.; Lipa, T.; Krawiec, P. Thinning of Apple Flowers with Potassium Bicarbonate (Armicarb®) in Organic Orchard. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2016, 15, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim, S.J. Chemical control of flower and fruit abscission in apple and pear. Acta Hortic. 1973, 34, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArtney, S. Effective use of apple blossom thinners. In Proceedings of the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable & Farm Market EXPO, Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 5–7 December 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pavanello, A.P.; Zoth, M.; Ayub, R.A.; de Souza Los, K.K. Different Methods of Thinning Influenced by Variety and Hail Nets in Apple Orchards. Agric. Res. Technol. 2019, 3, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulart, G.; de Andrade, S.B.; Schiavon, A.V.; Aguiar, G.A.; Malgarim, M.B. Metamitron and Different Plant Growth Regulators Combinations in the Chemical Thinning of ‘Eva’ Apple Trees. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2017, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.; Ottnad, S.; Kunz, A.; Damerow, L.; Blanke, M. Hail Nets Do Not Affect the Efficacy of Metamitron for Chemical Thinning of Apple Trees. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabardo, G.C.; Petri, J.L.; Hawerroth, F.J.; Couto, M.; Argenta, L.C.; Kretzschmar, A.A. Use of Metamitron as an Apple Thinner. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2017, 39, e514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.; Ottnad, S.; Kunz, A.; Damerow, L.; Blanke, M. Effect of Different Application Rates of Metamitron as Fruitlet Chemical Thinner on Thinning Efficacy and Fluorescence Inhibition in ‘Gala’ and ‘Fuji’ Apple. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 89, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.W.; Schupp, J.R.; Winzler, H.W. Effect of abscisic acid and benzyladenine on fruit set and fruit quality of apples. HortScience 2011, 46, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bound, S.A. Managing Crop Load in European Pear (Pyrus communis L.)—A Review. Agriculture 2021, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergun, M. Postharvest quality of ‘Galaxy’ apple fruit in response to kaolin-based particle film application. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2012, 14, 599–607. [Google Scholar]

- Shellie, K.C.; King, B.A. Kaolin-based foliar reflectant and water deficit influence malbec leaf and berry temperature, pigments, and photosynthesis. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2013, 2012, 12115. [Google Scholar]

- Conde, A.; Pimentel, D.; Neves, A.; Dinis, L.-T.; Bernardo, S.; Correia, C.M.; Gerós, H.; Moutinho-Pereira, J. Kaolin Foliar Application Has a Stimulatory Effect on Phenylpropanoid and Flavonoid Pathways in Grape Berries. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, D.M.; Puterka, G.J. Particle films: A new technology for Agriculture. Hortic. Rev. 2010, 31, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, L.E. Scientific basis of a unique formulation for reducing sunburn of fruits. HortScience 2011, 46, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, A.; Metcalf, S.G.; Buchner, R.P.; Fulton, A.E.; Lampinen, B.D. Physiological Effects of Kaolin Applications in Well-Irrigated and Water-Stressed Walnut and Almond Trees. Ann. Bot. 2006, 98, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wünsche, J.N.; Lombardini, L.; Greer, D.H. Surround Particle Film Applications—Effects on Whole Canopy Physiology of Apple. Acta Hortic. 2004, 636, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakalik, D.; Brown, M.G.; Peck, G.M. Fruitlet Thinning Reduces Biennial Bearing in Seven High-tannin Cider Apple Cultivars. HortScience 2024, 59, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertschinger, L.; Stadler, W.; Stadler, P.; Weibel, F.; Schumacer, R. New methods of environmentally safe regulation of flower and fruit set and of alternate bearing of the apple crop. Acta Hortic. 1998, 466, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, R.E.; Barden, J.A.; Polomski, R.F.; Young, R.W.; Carbaugh, D.H. Apple thinning by photosynthetic inhibition. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1990, 115, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, R.E.; Carbaugh, D.H.; Presley, C.N.; Wolf, T.K. The influence of low light on apple fruit abscission. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1991, 66, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, J.L.; Couto, M.; Gabardo, G.C.; Francescatto, P.; Hawerroth, F.J. Metamitron replacing carbaryl in post bloom thinning of apple trees. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2016, 38, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArtney, S.J.; Obermiller, J.D. Use of 1-Aminocyclopropane Carboxylic Acid and Metamitron for Delayed Thinning of Apple Fruit. HortScience 2012, 47, 1612–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.; Bonany, J.; Alegre, S.; Àvila, G.; Carbó, J.; Torres, E.; Recasens, I.; Martin, B.; Asin, L. Brevis thinning efficacy at different fruit size and fluorescence on ‘Gala’ and ‘Fuji’ apples. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 256, 108526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, J.A.; Bakker, C.J.; Beneff, A. Multi-year investigation on the rate, timing, and use of surfactant for thinning apples with post-bloom applications of metamitron. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2022, 102, 628–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.L. Crop Load Management of Apple to Optimize Fruit Quality and Economic Return. Acta Hortic. 2006, 772, 367–378. [Google Scholar]

- Basak, A. Efficiency of Fruitlet Thinning in Apple ‘Gala Must’ by Use of Metamitron and Artificial Shading. J. Fruit Ornam. Plant Res. 2011, 19, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Racskó, J. Crop Load, Fruit Thinning and Their Effects on Fruit Quality of Apple (Malus domestica Borkh.). J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 24, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, B.; Serra, S.; Musacchi, S. Optimizing Crop Load for New Apple Cultivar: “WA38”. Agronomy 2019, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopar, M.; Bolcina, U.; Vanzo, A.; Vecchione, A. Sugar and Organic Acid Content in Apple Juice. Acta Aliment. 2002, 31, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szot, I.; Lipa, T. Apple Trees Yielding and Fruit Quality Depending on the Crop Load, Branch Type and Position in the Crown. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2019, 18, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | No. of Flower Clusters [pcs·Tree−1] | Blooming Efficiency Index (BEI) [pcs·cm−2] | No. of Fruits [pcs·Tree−1] | Fruit Set [pcs·100−1 Flower Buds] | Yield [kg·Tree−1] | Cropping Efficiency Index (CEI) [kg·cm−2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 89.6 a 1 | 11.9 a | 66.3 cd | 74.6 cd | 6.35 d | 0.59 de |

| AS | 88.2 a | 8.80 a | 7.06 a | 7.92 a | 1.17 a | 0.10 a |

| B2 | 90.0 a | 12.0 a | 10.7 a | 11.9 a | 2.71 ab | 0.29 abc |

| KC50 | 92.5 a | 11.4 a | 57.4 c | 63.1 c | 6.67 d | 0.60 de |

| KC100 | 87.2 a | 9.72 a | 58.7 c | 67.6 c | 6.93 d | 0.65 e |

| KC200 | 88.1 a | 9.20 a | 75.4 cd | 85.2 cd | 10.1 e | 0.85 f |

| B1 + KC50 | 91.1 a | 9.51 a | 28.5 b | 31.2 b | 4.79 cd | 0.40 bcde |

| B1 + KC100 | 98.0 a | 10.0 a | 33.8 b | 34.6 b | 6.21 d | 0.52 cde |

| B2 + KC50 | 94.8 a | 12.1 a | 18.5 ab | 19.9 ab | 2.62 ab | 0.26 ab |

| B2 + KC100 | 88.9 a | 10.1 a | 18.3 ab | 20.7 ab | 3.93 bc | 0.35 bcd |

| Treatment | Internal Ethylene Concentration [μL·L−1] | Starch Index [-] | Streif Index [-] | Apple Skin Coloration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L [-] | a [-] | b [-] | Hue (h°) | Chroma (C) | ||||

| Control | 0.143 ab 1 | 4.60 a | 0.143 c | 42.1 a | 23.8 a | 7.93 a | 1.25 a | 25.1 a |

| AS | 0.094 bcd | 6.73 ab | 0.094 abc | 42.2 a | 21.8 a | 6.73 a | 1.27 a | 22.9 a |

| B2 | 0.096 abc | 6.30 ab | 0.096 abc | 39.6 a | 20.4 a | 6.53 a | 1.26 a | 21.4 a |

| KC50 | 0.135 a | 4.96 a | 0.135 bc | 41.6 a | 23.4 a | 7.86 a | 1.25 a | 24.7 a |

| KC100 | 0.140 a | 4.70 a | 0.140 c | 42.7 a | 22.5 a | 7.70 a | 1.24 a | 23.8 a |

| KC200 | 0.130 a | 5.60 ab | 0.130 abc | 41.2 a | 23.0 a | 7.16 a | 1.27 a | 24.1 a |

| B1 + KC50 | 0.101 ab | 6.23 ab | 0.101 abc | 41.1 a | 22.0 a | 7.13 a | 1.26 a | 23.1 a |

| B1 + KC100 | 0.088 abc | 6.56 ab | 0.088 ab | 40.5 a | 20.7 a | 6.33 a | 1.28 a | 21.7 a |

| B2 + KC50 | 0.082 cd | 7.10 b | 0.082 a | 41.0 a | 20.5 a | 6.50 a | 1.27 a | 21.6 a |

| B2 + KC100 | 0.096 d | 6.73 ab | 0.096 abc | 40.1 a | 20.1 a | 6.33 a | 1.27 a | 21.1 a |

| Treatment | Flesh Firmness [N] | Soluble Solid Content [°Brix] | Titratable Acidity [% Malic Acid] | SSC–Acidity Ratio [-] | Fruit Mass [g] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 72.4 a 1 | 11.2 a | 0.39 a | 28.6 ab | 171 a |

| AS | 74.7 ab | 12.1 ab | 0.44 ab | 27.2 ab | 197 b |

| B2 | 73.9 ab | 12.6 ab | 0.47 bc | 26.8 ab | 192 b |

| KC50 | 73.1 a | 11.3 a | 0.39 a | 28.8 ab | 196 b |

| KC100 | 75.4 ab | 11.9 ab | 0.39 a | 29.9 b | 188 b |

| KC200 | 73.8 ab | 11.4 a | 0.41 a | 27.6 ab | 169 a |

| B1 + KC50 | 73.6 ab | 12.0 ab | 0.40 a | 29.5 b | 186 b |

| B1 + KC100 | 73.7 ab | 13.3 b | 0.38 a | 34.6 c | 189 b |

| B2 + KC50 | 75.9 ab | 13.2 b | 0.51 c | 26.0 ab | 186 b |

| B2 + KC100 | 79.5 b | 12.7 ab | 0.51 c | 24.7 a | 183 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Przybyłko, S.; Marszał, J.; Kowalczyk, W.; Szpadzik, E. Effect of Kaolin Clay on Post-Bloom Thinning Efficacy, Cropping, and Fruit Quality in ‘Gala Vill’ Apple (Malus × domestica) Cultivation. Agriculture 2025, 15, 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15040440

Przybyłko S, Marszał J, Kowalczyk W, Szpadzik E. Effect of Kaolin Clay on Post-Bloom Thinning Efficacy, Cropping, and Fruit Quality in ‘Gala Vill’ Apple (Malus × domestica) Cultivation. Agriculture. 2025; 15(4):440. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15040440

Chicago/Turabian StylePrzybyłko, Sebastian, Jacek Marszał, Wojciech Kowalczyk, and Ewa Szpadzik. 2025. "Effect of Kaolin Clay on Post-Bloom Thinning Efficacy, Cropping, and Fruit Quality in ‘Gala Vill’ Apple (Malus × domestica) Cultivation" Agriculture 15, no. 4: 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15040440

APA StylePrzybyłko, S., Marszał, J., Kowalczyk, W., & Szpadzik, E. (2025). Effect of Kaolin Clay on Post-Bloom Thinning Efficacy, Cropping, and Fruit Quality in ‘Gala Vill’ Apple (Malus × domestica) Cultivation. Agriculture, 15(4), 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15040440