2. Methodology

Many studies by both foreign and Russian scientists have examined the issues of competition and competitiveness. However, a common concept for these definitions as well as a common methodology for calculating the indicators of competitiveness have yet to be developed because competitiveness is a complex concept that includes many significantly different objects and factors. As noted by Fatkhutdinov, competitiveness integrates technological, economic, managerial, marketing, psychological, and other characteristics of the subject and object, which depend on specific market conditions [

3]. Another important aspect of the assessment of competitiveness is the level on which the assessment is conducted (micro, meso, or macro). For example, competitiveness can be assessed at the level of the production of goods at a particular enterprise in comparison with other enterprises in the industry, or at the level of the region or country in comparison with the production of similar goods in other regions and countries.

Porter defined the competitiveness of a product, service, or a subject as the ability to act on the market on par with similar goods, services, or competing subjects within market relations [

4]. The main criteria for assessing competitiveness is the ability to compete in price and quality, while ensuring a steady increase in production [

5]. In this regard, various authors have used the concept of the competitive advantage of the characteristics and properties of a product or brand that result in a certain superiority over their direct competitors [

6].

Various methods are available that use various aspects of competitiveness for assessing the competitiveness of goods. One of the most common methods is the assessment of competitiveness based on the calculation of indices of comparative competitive advantages. Among them, the most widely used is the revealed comparative advantage index introduced by Balassa. The index is determined by the ratio of the export of goods to the total export of a country to the world export of this product to the world export of all goods [

7,

8]. Various authors developed modifications of this index: the Proudman–Redding index, which corrects the distortions that arise when comparing large and small countries by normalizing the Balassa index to the average value for goods for a particular country [

9]; the Bowen index, which uses the calculation data on production in the country [

10]; and the Lafey index, which considers a country’s e exports and imports [

11].

A similar analysis using the calculation of the coefficient of comparative competitive advantages was used by Gibba, who determined the competitive advantages of countries involved in world trade of vegetables [

12]; Smutka et al. analyzed the effect of product embargo on trade relations between Russia and the Euorpan Union (EU) [

13]; and Esquivias analyzed the dynamics of the comparative advantages of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations ASEAN countries and identified their export specialization on the basis of trade flow information [

14].

Among other approaches to the definition of competitiveness, one methodology can be singled out based on the evaluation of goods from the point of view of their ability to satisfy consumer demands (the Rosenberg model). This method considers the importance of product characteristics from the consumer viewpoint. This model was used in the analysis by Bronnikova et al. [

15] and was used the calculation of the integral indicator, for example, if the assessment of the competitiveness of an object is conducted on the basis of a large group of indicators [

16].

These methods can be used to assess the competitiveness of agricultural products. However, in our opinion, for the analysis of product competitiveness at the macrolevel, the most expedient approach is the use of the integral index because a complex indicator synthesizes various product characteristics. This indicator was used to reveal the intercountry competitiveness of the agricultural products of the EAEU countries.

To evaluate the competitiveness of the EAEU countries for various types of agricultural products, we propose a methodology for assessing the competitiveness of products based on the calculation of an integrated indicator that includes five factors: average producer price (

AVPij), export price (

EX_Pij), output (

Qij), share export in production volume (

EX_Qij), price competitiveness factor (

Com_Cij) defined as the ratio of average prices of agricultural producers, and import prices (

IM_P), considering imports, duties, customs duties, value-added tax (

VAT), and excise duties [

16]. This indicator allows for the assessment of the competitiveness of agricultural products at various levels, from production and realization to the level of mutual (within the EAEU) and foreign trade.

To ensure the comparability of the calculations, each

i kind of product for each

j EAEU country must be normalized using the following maximising equation:

where

AVPij is the average producer price,

where

EX_Pij is the export price,

Qij is the output,

EX_Qij is the share export in production volume, and

Com_Cij is the price competitiveness factor.

To calculate the integral indicator of competitiveness, these indicators were divided into two groups. The first group of indicators determines the competitiveness of products based on price factors (AVPij, EX_Pij, and Com_Cij); therefore, products become more competitive with a decrease in these indicators. The second group of indicators characterizes the competitiveness of products based on the production volumes and the share of exports (Qij and EX_Qij); therefore, the products become more competitive with an increase in these indicators.

The calculations were based on these multidirectional factors. To ensure their comparability, an additive model of deterministic factor analysis was used. On the basis of normalized factors, an integral indicator of competitiveness was determined for each type of agricultural product of the EAEU states (

INT_Cij):

The comparison of the competitiveness of EAEU countries was based on the values of this indicator for certain products for a particular year. The higher the integrated indicator of competitiveness, the more competitive the products in both the domestic and foreign markets.

On the basis of the integral index of competitiveness, two tasks are solved. The first task was to compare and rank the EAEU countries in terms of product competitiveness. The second task was to assess the degree of influence of the indicated factors (AVPij, EX_Pij, Com_Cij, Qij, and EX_Qij) on the level of competitiveness of various types of products in each EAEU country as well as ranking these factors.

The first task was to compare and rank the EAEU countries in terms of product competitiveness. To solve this problem, we constructed a regression multi-country model of the first type:

where

b0 is the conditional start of the regression model (constant);

bi is the coefficient of pure regression;

INT_w is the the weighted average integral indicator of competitiveness;

RFij,

RBij,

KZij,

AMij, and

KGij are integral indicators of competitiveness of

i products in

j state (Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan), respectively; and

ε is the random error of the regression model. This model enables the assessment of the competitiveness of the EAEU countries over a long period of time.

One dependent variable in this model wisas the weighted average indicator of the competitiveness of grain and its processing products, in general, for the EAEU INT_w. To determine this indicator, we had to calculate the integral indicators of competitiveness (RFij, RBij, KZij, AMij, and KGij) for i type of product j of the country using Equation (6). Then, we calculated the weighted average indicator, INT_w, as weights used for share j of the state in the total volume of gross grain production in the EAEU.

The second task was to assess the degree of influence of the indicated factors (AVPij, EX_Pij, Com_Cij, Qij, and EX_Qij) on the level of competitiveness of various types of products in each EAEU country as well as ranking these factors. The method includes: (1) calculating the integral indicator of product competitiveness in the EAEU countries, (2) cross-country regression analysis of the integral indicator of dynamic competitiveness, and (3) correlation and regression analysis to identify the degree of influence of AVPij, EX_Pij, Com_Cij, Qij, and EX_Qij on the integral indicator of product competitiveness in the EAEU countries.

The degree of influence of price determinants, factors of the volume of production, and export of grain on the integral indicator of its competitiveness were estimated on the basis of the coefficients of pure regression (

bn) for the

j state and

i type of output of the grain market using the models of multiple regression:

where

INT_C is the integral indicator of competitiveness;

AVP is the average producer prices of grain products in the EAEU countries, US dollars;

EX_P is the export prices for grains and products of its processing in the EAEU countries, US dollars;

Com_C is the coefficient of price competitiveness;

Q is the volume of cereal production from the member states of the EAEU countries, in thousand tons; and

EX_Q is the share of grain exports from the EAEU countries in total production.

Thus, our method allows, first, identifying which of the EAEU countries is the most competitive in various agricultural markets, and, second, determining which of the factors has the greatest influence on the formation of competitive advantages in each EAEU country.

During the research, a set of methods was used: a monographic study of the research subject, expert assessments, statistical methods, and econometric modeling. Through the econometric model, the main quantitative relationships between the analyzed economic phenomena and processes can be described [

17]. The construction of competitiveness models and the evaluation of their parameters were conducted in a package in the applied econometric program Eviews 9.5 (IHS Global Inc., Irvine, CA, USA).

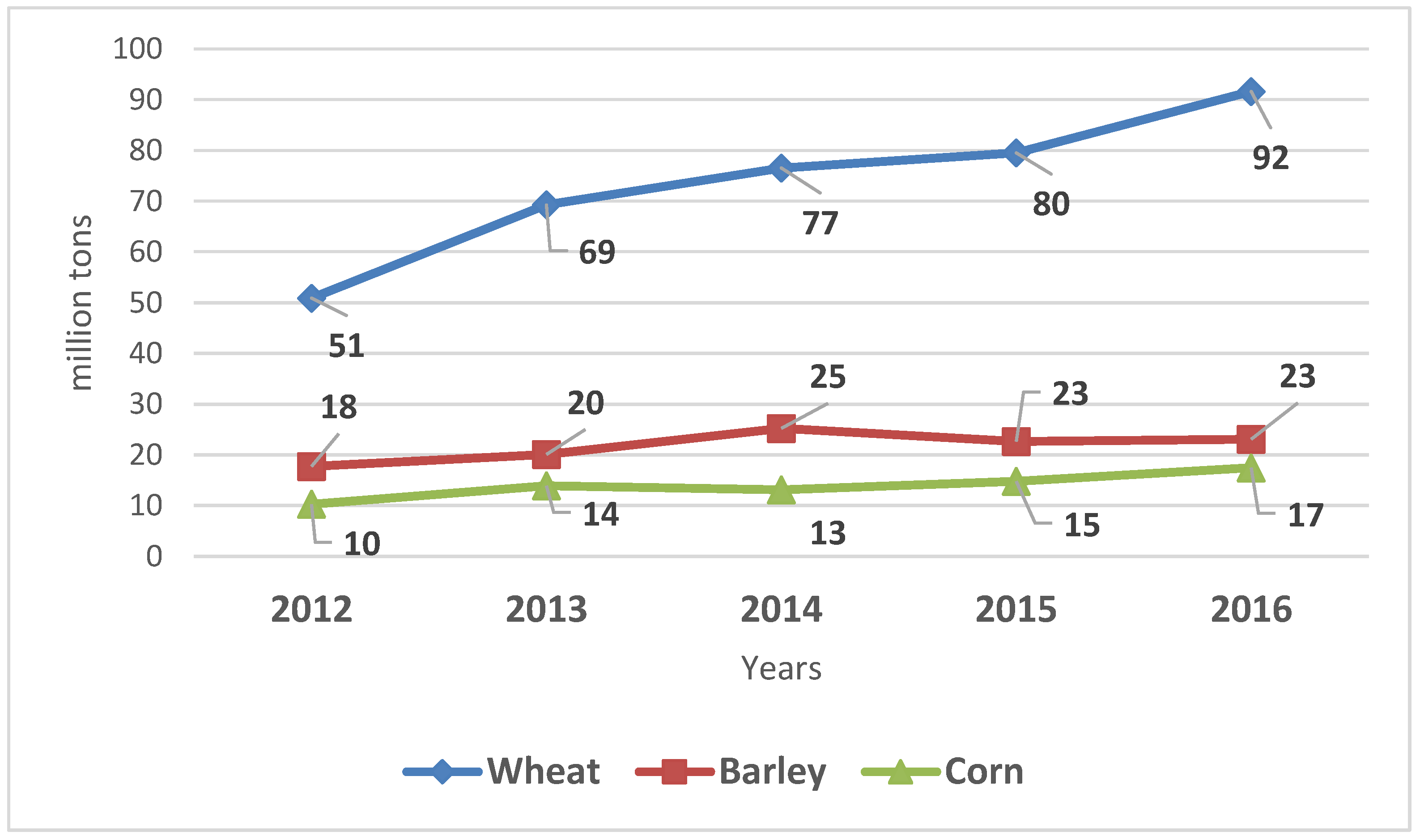

We used the annual data of the state statistical offices of the EAEU countries and the international trade database United Nations (UN) Comtrade on the volume of production, export-import operations, and prices for wheat, barley, corn, wheat flour, and pasta by the EAEU countries for the period of 2010–2016 in this study.

4. Regression Analysis of Grain Competitiveness Factors

4.1. Wheat

Reflecting the dependence of the integrated indicator of wheat competitiveness in the EAEU on the parameters of the competitive advantages of individual EAEU countries, the multiple linear regression model takes the form

The values of standard errors are indicated in parentheses at a 5% level of statistical significance.

The parameters of the obtained econometric model show that the most competitive in the 2010–2016 period was wheat produced in the Russian Federation (the largest coefficient of pure regression with variable RF), followed by the Republic of Kazakhstan and the Republic of Belarus (

Table 2).

Using correlation-regression analysis, we estimated the strength and direction of the influence of price and non-price factors on the competitiveness of wheat in each individual country of the EAEU. The results of the analysis are presented in

Table 3.

The data in

Table 3 show that the level of wheat competitiveness in the Russian Federation was most influenced by factors such as production volume and average producer prices. The gross harvest of wheat in farms of all categories during 2010–2016 increased by almost 80% from 41.5 million tons to 73.3 million tons. Along with the growth in production, volumes of wheat supply to foreign markets also increased; in relative terms, this figure more than doubled. However, the outstripping growth in wheat production (supply), when compared with the dynamics of demand in domestic and foreign markets, exerts pressure on both the domestic and export prices of agricultural producers. In particular, average domestic wheat prices reached peak values in 2013 at USD

$244/ton, before the price steadily decreased to USD

$132/ton in 2016. The same trend was observed in the export prices for Russian wheat. This strengthens Russia’s competitive position in foreign markets.. The price level for Russian wheat is much lower than in the leading export countries of this product in the world. For example, the average export price for wheat produced in Russia in 2016 was USD

$166.5/ton, and in the USA, it was USD

$224.9/ton, and USD

$228.5/ton in Canada [

25].

In the Republic of Belarus, the factors exerting the greatest influence on the competitiveness of wheat included domestic producer prices and the share of exports in the total volume of gross production. In particular, the wheat prices of Belarusian agricultural producers reached the highest values in 2013 at USD $233/ton, which fell steadily in subsequent years, reaching USD $127/ton in 2016. In this case, the gross collections of wheat increased. Thus, in 2016 compared to 2010, the increase was 34.5%. The volumes of export deliveries grew almost 19 times from 5 to 91.6 thousand tons, and the share of exports increased from 0.28% to 3.9%.

In Kazakhstan, the most important factors affecting wheat competitiveness were the average producer prices, export prices, and production volumes. From 2013, the negative dynamics of the average producer prices remained at a level that was almost halved by 2016; the export prices showed a decrease of about 36%. According to the price criteria, Kazakhstan had the greatest competitive advantages among all EAEUcountries. In the period of 2010–2016, Kazakh agricultural producers increased the volume of wheat production from 9.6 to 15 million tons. However, against the background of growth in production volumes, the share of exports decreased. In particular, in 2010, the volume of wheat deliveries from Kazakhstan to foreign markets amounted to 5 million tons, which was more than half of the total production of this crop. This increased in 2012 when exports amounted to 7.5 million tons, about 76% of gross harvest, and then by 2016, this indicator decreased to 4.4 million tons, about 30% of the total volume of production.

4.2. Barley

The multiple linear regression model, reflecting the dependence of the integral indicator of barley competitiveness in the EAEU on the parameters of the competitive advantages of the countries studied, takes the form

The values of standard errors are indicated in parentheses at a 5% level of statistical significance.

The parameters of the obtained econometric model showed that the barley produced in the Russian Federation had the most competitive advantage in the period from 2010 to 2016 (the largest coefficient of pure regression with variable RF), followed by the Republic of Kazakhstan, then the Republic of Belarus (

Table 4).

Using correlation and regression analysis, we estimated the degree of influence of the studied factors on the competitiveness of barley. The results of the analysis are presented in

Table 5.

On the basis of the data presented in

Table 5, we concluded that, in the Russian Federation, the most significant factors of barley competitiveness are volume of production, average producer prices, and the coefficient of price competitiveness. In particular, during the period 2010–2016, the volume of barley production in Russia more than doubled from 8.35 to 18 million tons, which is about 80% of the production of this crop as a whole for all EAEU countries. The dynamics of barley producer prices was characterized by a negative trend, as was the case for wheat. The average prices for Russian barley reached the lowest values in 2013 at USD

$216/ton, and by the end of 2016, prices had fallen almost twofold to USD

$116/ton. Notably, the prices for barley from Russian agricultural producers were the highest among all EAEU countries. The level of export prices in 2016 allowed Russia to confidently compete with the leading countries, France, Australia, and Germany, in terms of barley exports worldwide. Export prices for barley in these countries in 2016 were USD

$182/ton, USD

$195/ton, and USD

$173/ton, respectively, which was much higher than the export prices for Russian barley, the price of which in 2016 was USD

$148/ton.

In the Republic of Belarus, the average producer prices and the price competitiveness factor had the greatest impact on the competitiveness of barley. The least significant factor was the volume of production for the period of 2010–2016. The gross harvest of barley in farms of all categories declined by almost 38% from 1.97 million tons to 1.23 million tons in this period.

In Kazakhstan, the competitiveness of barley was mainly influenced by the price factors. The current level of domestic and export prices for barley in Kazakhstan was the lowest in the grain market of the Unified Energy System (USD $77/ton and USD $95/ton, respectively). The coefficient of price competitiveness did not significantly affect the level of competitive advantages of barley in the internal EAEU market.

4.3. Corn

The multiple linear regression model, reflecting the dependence of the integrated indicator of corn’s competitiveness in the EAEU on the parameters of the competitive advantages of individual countries of the Union, takes the form

The values of standard errors are indicated in parentheses at a 5% level of statistical significance.

Parameters of the obtained econometric model showed that, from 2010 to 2016, the most competitive country in corn production was in the Russian Federation (the highest coefficient of pure regression with variable RF), followed by the Republic of Kazakhstan and the Republic of Belarus (

Table 6).

Using correlation and regression analysis, we estimated the degree of influence of the studied factors on the competitiveness of corn. The results of the analysis are presented in

Table 7.

The data in

Table 7 showe that the price competitiveness ratio had the greatest impact on the level of corn competitiveness in the Russian Federation. The average producer prices of corn in Russia in 2016 was about USD

$125/ton. The second and third places in terms of impact on the competitiveness of Russian corn in 2016 were the share of exports in production, at 35%, and export prices at USD

$929/ton, respectively. The volume of production of this crop grew from 3.1 million tons in 2010 to 15.3 million tons in 2016, i.e., by almost five times, and not only satisfied the domestic demand for corn for grain, but also increased the volume of supply of corn to foreign markets from 0.3 to 5.32 million tons in the period. The current prices allow for strong competitive positions for corn grain produced in Russia, both in the domestic and export markets, for agricultural products to be maintained.

In the Republics of Belarus and Kazakhstan, corn for grain is produced in small volumes, which were 740,000 and 762,000 tons in 2016, respectively. In the period from 2010 to 2016, the volumes of the gross harvest of this crop grew steadily. In Belarus for the period under review, the growth was 34.3% and that in Kazakhstan was 65%. Due to the comparatively small volumes of corn production and export in Kazakhstan, its competitiveness was influenced by average producer prices, whose level was the lowest among all EAEU countries, as well as the ratio of domestic prices to corn prices (the price competitiveness factor). The Republic of Belarus was the least competitive level in both domestic and export prices.

Thus, the proposed econometric model enabled the identification of the competitive advantages of Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus in the grain market, and the degree of influence of the studied factors on the competitiveness of wheat, barley, and corn in the domestic EAEU market. To assess the competitiveness of products in foreign markets, we compared domestic producer prices with producer prices in the countries recognized as global leaders in exporting these products. Analysis was conducted for Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia (

Table 8).

Thus, in Kazakhstan and Russia, the producer prices for wheat, barley, and corn were lower than in the countries who were the main exporters of these products in the world, showing a significant competitive advantage in price. In the Republic of Belarus, producer prices for these crops were higher than in the countries leading in terms of global exports, which means that these products are less competitive in Belarus.