1. Introduction

Social affiliation and interaction with landscape imbue space with meaning, creating significant places (

Tuan 1977). In Bhutan, located between India and China in the eastern Himalayan Range, long-term social affiliation and interaction with the landscape has contributed to a landscape lush with sacred places. Widely known for its rich biological diversity, its vast forests, and its designation as a ‘biodiversity hotspot,’ Bhutan’s tradition of sacred natural sites may cultivate socio-cultural practices that contribute to preserving this biodiversity.

Origin stories of the arrival of Buddhism in Bhutan present active engagement with the landscape as being inherent to and inextricable from the practice of the religion: a topophilia—or love of landscape—woven in the history and consciousness of the Bhutanese (

Tuan 1972). Drawing inspirational power from the introduction of Buddhism in the seventh century and the legendary arrival of Guru Rimpoche, also known as Padmasambhava, in the eighth century, the forms of Buddhism practiced in contemporary Bhutan express a relational ontology, that perceives and creates particular spiritual geography.

Himalayan Buddhism did not eliminate autochthonous deities of the landscape, as for example, Christianity largely did in Europe (

Schneider 1991;

Nixey 2018). Instead, according to oral and literary tradition, local deities were subdued and converted to Buddhism, with specific sites on the landscape identified as their abodes. Guru Rimpoche is understood to have subdued the local autochthonous deities and spirits who inhabit and oversee various aspects of the geographical terrain. He converted them to sworn protectors of Buddhism, thereby giving rise to a landscape in which natural features are infused, through a transitive property of contagion, with the Buddha dharma. The deity abodes or “citadels” (

pho brang in Dzongkha, one of the national languages of Bhutan) evoke both reverence and caution, as villagers fear upsetting the unruly deities.

Local deities mediate the relationship of people and landscapes to such an extent that the social and spiritual interactions of humans and nonhumans result in their mutual constitution. The abodes or “citadels” of local deities and spirits can be considered a type of “sacred natural site”, where biological and cultural aspects of the landscape are intertwined. Revered and protected by diverse cultures, sacred natural sites have been defined as “areas of land or water having special spiritual significance to peoples and communities” (

Wild and McLeod 2008), encompassing a wide range of geographical features, including lakes, rivers, water springs, mountains, cliffs, caves, and rocks. Sacred natural sites are a global, trans-cultural phenomenon, documented on every continent except Antarctica.

1 In the 1970s,

Gadgil and Vartak (

1976) brought scientific attention to the potential connections of sacred groves and biodiversity conservation with their early work on ethnobotany in India, which is believed to have 150,000 to 200,000 sacred groves (

Gold and Gujar 1989;

Chandran and Hughes 1997;

Malhotra et al. 2000;

Wild and McLeod 2008). Researchers estimate that there may be as many as quarter million sacred natural sites worldwide, although a full accounting of sacred natural sites has not been undertaken (

Dudley et al. 2005;

Wild and McLeod 2008). The blending of natural and spiritual values in sacred natural sites is seen as beneficially contributing to biocultural conservation—the preservation of local or indigenous lifeways, languages, and cultures—along with biological and ecological conservation. Sacred natural sites may serve as sites for the preservation of the regenerative potential of local flora, serving as in situ repositories for healthy specimens, and as reservoirs of biodiversity in a broader landscape dominated by human usage.

Ecologists have hypothesized that recognition of the useful characteristics of particular plants led to the veneration of certain species (

Ramakrishnan 1996), and further that the proscription of resource harvest from sacred natural sites may contribute to dense reservoirs of highly-valued trees providing seed stock for further regeneration (

Sharma et al. 1999). This dynamic can be seen in the deity-inhabited sacred natural sites of Bhutan. Of the 26 deity citadels studied in Trashiyangtse, eastern Bhutan, 60% were dominated by one of four highly-valued species of trees:

Quercus griffithii (oak),

Schima wallichii (needlewood),

Alnus nepaliensis (alder), and

Juglans regia (English walnut), as measured by estimations of stem frequency (

Allison 2004). These species all have a great deal of utility, playing multiple roles in the village subsistence economy (

Wangchuk 2000). Oaks provide fodder, fuelwood, cremation wood, timber, and medicinal acorns, and support the growth of edible mushrooms, along with maintaining soil fertility and moisture. Needlewood (

Schima wallichii), commonly found on abandoned shifting cultivation lands, provides sturdy wood for ploughs and furniture, as well as firewood. Alder (

Alnus nepalensis) is also common after disturbance, and may be used for firewood, some construction, green manure and animal bedding. Walnut (

Juglans regia) provides high quality timber, fodder, food, medicine, dye, and insecticide.

Schima wallichii and

Quercus griffithii, found together in almost one-quarter of the deity citadels, serve a wide variety of uses: those of fuel, fodder, food, timber, and medicine. The utility represented by the tree species of the deity citadels suggests that they are important in sustaining human communities and may provide support for biocultural resilience (

Allison 2004). As local people indicated that they would not harvest materials from these sites out of fear of retribution from the deity, the deity citadels may serve as refugia where ecologically significant flora and fauna can regenerate in a matrix of anthropocentric and agricultural uses of the land. Similarly, in Radhi and Shaba of nearby Trashigang

dzongkhag [district], “100 percent of the respondents to the interviews in both the Gewogs [administrative subunit of a district] said that they would never destroy a religious forest or do anything forbidden by the local religious persons” (

Wangchuk 2000, p. 84). The researcher noted that the “religious forest” was “well stocked” while other nearby forests had experienced heavy human use. More recently, researchers in Soenakhar and nearby villages in Mongar, eastern Bhutan, found that the “mountain closure” required by the

tsen (Tib.

btsan) protector deity was a widely observed method of moderating resource use and restricting human impact on the higher reaches of the mountains (

Kuyakanon and Gyeltshen 2017).

Bhutan’s long cultural and religious history interwoven with the landscape have created a uniquely Bhutanese form of traditional ecological knowledge that contributes to both cultural continuity and ecological resilience. Ecologically, resilience is defined as the amount of disturbance a system can absorb before changing to a different ecological state (

Gunderson 2000;

Holling 1973). Resilience offers the ability to recover from shocks to the system and return to the same state. As resilience declines, the amount of disturbance that can be absorbed declines. To maintain resilience, a system must

resist that which disturbs the system and brings about changes in state.

In honoring the value of intact biodiversity, sacred natural sites contribute to the resistance of economic forces that would commodify all life as grist for the capitalist mill. Here, I adopt the definition of “everyday forms of resistance” from the political ecologist James C. Scott, who includes such local, informal, and covert acts of resistance to state or hegemonic power as “passive noncompliance, subtle sabotage, evasion, and deception” (

Scott 1985, p. 31). Ritual actions that venerate sacred natural sites are an implicit expression of passive noncompliance—and indeed, an expression of an alternative—in relation commodifying and appropriating political-economic forces. By maintaining and enacting a worldview that recognizes forested landscapes as more than simply material insensate “stuff” to be exploited by markets, Bhutanese villagers resist the inroads of a capitalist mentality, even as infrastructure development, fostered by global capitalism, brings material benefits in the form of electricity and transportation to their villages. Villagers implicitly reject the categories of global capitalism and re-instantiate a symbolic order in which all sentient beings have value (cf.

Scott 1985).

Sacred natural sites focus attention on non-economic, eco-spiritual values. In focusing attention on the value of living biodiversity, seen as essential to the expression of spiritual values, the veneration of sacred natural sites offers a counterpoint to globally powerful consumptive values. In addition to serving a value or motivation for protecting ecological surroundings as sacred natural sites, spirituality that perceives active ‘hierenergetic’ forces in the landscape can function as a space of ideological freedom, loosening the grip of both structured canonical religion and state economic and political control. While the Bhutanese deities of the land have been incorporated into Vajrayana Buddhism in Bhutan, as this paper shows, their subjugation is incomplete, allowing for the unruly eruption of the unexpected. Direct connection with powerful spiritual forces allows an access to expansive, uncontrolled possibility that can unmoor believers from the hegemonic demands of the state and other superstructures of social organization, providing a well-spring of resistance (

Gottlieb 1999). This paper examines the mutual constitution of sacred places, spiritual perceptions, and biocultural resilience in Bhutan, arguing that the perception of landscape-dwelling deities contributes to cultural resistance and ecological resilience. In focusing attention and practice on particularly rich eco-cultural sites on the landscape, sacred natural sites become

places of resistance and resilience: they are sites of cultural resistance to geopolitical forces conveying values and practices at odds with Bhutan’s cultural traditions, as well as sites of ecological resilience that contribute to Bhutan’s maintenance of its biocultural heritage.

2. Methodology

This analysis of place as sacred arises from an ethnographic study of the connection of religious beliefs and practices, environmental imaginaries, and the construction of socio-natural place in Bhutan, conducted on six visits to Bhutan, ranging in length from one to eight months, between 2001 and 2008. I used ethnography to identify patterns that could be used to generate grounded theory, relying on unstructured and semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and document analysis to allow general theories to arise from local dynamics (

Glaser and Strauss 1967). Participant observation and semi-structured interviews were conducted with villagers and government officials in eight of Bhutan’s twenty districts. Interviews took place in people’s homes, in offices, in restaurants and taxis, and at festivals. Participant observation—“study of people in their own time and space, in their own everyday lives” (

Burawoy 1991)—in meetings, events, religious observations and daily life provided a means of corroborating the interviews, and added significant depth to my understanding of life in Bhutan. Unattributed statements draw on my fieldwork in Bhutan.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in Sharchopkha, Khengkha, Nepali, or Dzongkha, with an interpreter, or in English without an interpreter. The two national languages of Bhutan are Dzongkha, a variant of Tibetan, and English, widely spoken by educated people. Given prevalence of English among educated people, local language mastery is nearly impossible (

Penjore 2013, p. 154). Estimates of the number of different languages spoken in Bhutan range from 19 to 23 (

van Driem 2004;

Simons and Fennig 2017). Though I studied Tibetan, Dzongkha, and Nepali, the government asked me to conduct my research in eastern and central Bhutan where Sharchopkha and Khengkha, which are not formally written or taught, are the primary languages. For this reason, and to adhere to Bhutanese government protocol, I worked and traveled with several different Bhutanese counterparts, including Tashi Wangdi, Phuntsho Dorji, Prem Kumari, Sonam Gyamtsho, and Karma Yangzom, who provided language and cultural interpretation.

The beliefs and practices discussed here are those of the Buddhist majority in the eastern, central, and western (but not southern) parts of the country, with particular focus on the Nyingma Buddhists of eastern Bhutan. In a country as linguistically and culturally diverse as Bhutan, there are important alternatives to this story. Approximately one-quarter of the Bhutanese, found mainly in southern Bhutan, are Nepali-origin Hindus. While the 2008 Constitution provides for freedom of religion, the

Lhotsampa (“southerner”) Hindu minority has been subject to social and economic marginalization and persecution. Michael Hutt’s

Unbecoming Citizens (

Hutt 2003) discusses the details of this contentious situation. The capital city, Thimphu, is also home to a few Christians, whose worldview is at odds with the one described here.

3. Spiritual Landscape Ecology of Bhutan

Landscape ecology is classically defined as the study of ecological patterns and processes over time (

Turner 1989). Incorporating the spiritual landscape, both internal and external, into this study of ecology broadens the consideration of influences on the landscape. The history of religious avatars and their movement across the Himalayas expands the study of landscape ecology to include religious geography, pilgrimage, and spiritual perceptions of landscape.

In Bhutan, concerns about territory, landscape, and its qualities—both material and spiritual—extend back a millennium at least. Since the arrival of Buddhism in the seventh century, Bhutan has repelled attempts at colonization or annexation, creating a unique continuity of culture and memory (

Phuntsho 2013;

Aris 1979). The government of Bhutan often touts its position as the only remaining Mahayana Buddhist kingdom in the world, a feature that defines many of its social, cultural, and political characteristics.

2 The Vajrayana path of Mahayana Buddhism is deeply influential, guiding about three-quarters of the population.

3 Observing the vibrancy of the Vajrayana Buddhist tradition, Lopen Gembo Dorji, advisor to Bhutan’s Central Monk Body, has likened Bhutan to a “giant dialysis machine where one can avail free treatment and purification”, noting that sacred sites are not only historically significant, but also offer spiritual blessings gained through proximity (

Dorji 2016). Vajrayana Buddhism is further divided into four schools: the Sakya, Nyingma, Kagyu and the Gelug. Of these, followers of the Drukpa Kagyu predominate in western Bhutan, while inhabitants of eastern Bhutan follow the Nyingma tradition.

4 As understood and practiced in Bhutan, Vajrayana Buddhism—especially that of the Nyingma school found in the eastern part of the country—maintains a particular sensitivity to and engagement with the natural landscape.

Built and natural sacred sites define the landscape: Buddhist monasteries, temples, prayer wheels, and

chortens (Tib.

mchod rtens; white-washed stone reliquaries) sanctify the landscape (

Allison 2015). Proximity to sacred sites and figures provides blessing in the Vajrayana tradition. Thus, pilgrimage through the landscape to sacred sites generates religious merit while venerating and retracing the paths of historical religious figures. Monasteries, many of which were built by, or at the direction of historical religious personages, sit on mountaintops, presiding above the surrounding valleys as landmarks, and organizing the landscape into a

mandala, a circular diagram that is a representation of the entire universe from the perspective of an awakened one. Like a form of Buddhist “systems theory”, the mandala reveals the inherent emptiness of phenomena, the inextricable interconnections among arising phenomena, and the complete awakening that is always already present (

Simmer-Brown 2002).

The built and sacred natural sites in Bhutan conform to what geographer of religion Roger Stump identifies as historical, hierenergetic, and ritual categories of sacred space (

Stump 2008, p. 302). Historical sacred sites draw power from historical events that occurred there, like the sacred sites that commemorate the visits of great Buddhist teachers. Hierenergetic sacred space provides the site of contact through which religious practitioners may gain access to “manifestations of superhuman power and influence” (

Stump 2008, p. 302), as the Bhutanese experience when they perceive a landscape deity or its influence on the landscape. Ritual sacred space can be created through repeated ritual use, or can be chosen for rituals based on perceptions of sanctity (

Stump 2008, p. 304), as with the white-washed stone chortens that contain sacred relics, and shrines or altars for offerings within sacred natural sites. Each of these practices of recognizing the sacred in the landscape has multiple forms, all grounding Bhutanese Buddhist culture and belief in particular geographical places.

The establishment of Buddhism in Bhutan grounded the religion in the landscape from its very earliest days, echoing the Tibetan tradition of geomantic divination in the process of state formation (

Mills 2007). According to legend, Buddhism came to Bhutan in the seventh century when the Tibetan king Songtsen Gampo, the 32nd king of the Yarlung dynasty who ruled Tibet from c. 627 to 649, built two temples in Bhutan according to a geomantic system taught by his Chinese wife. The Chinese queen employed her divination chart to discover that a supine demoness lay over Tibet, causing the Himalayan landscape to be full of savagery and barbarism (

Aris 1979, p. 13;

Gyatso 1988;

Mills 2007;

Phuntsho 2013, p. 79). The two temples were among the twelve—or 108, according to some later accounts that adopt Buddhism’s auspicious number—that Songtsen Gampo built around the region to pin down the demoness who was ravaging the region and preventing the spread of Buddhism (

Phuntsho 2013, p. 80). As

Janet Gyatso (

1988) observes, such pinning and immobilizing of powerful indigenous spiritual, often feminine-inflected, sites for the purpose of religious conversion has a long history. Importantly, in Bhutan, the suppression of the local spirits was incomplete.

Two of these, Kyichu, in the Paro Valley, and Jambey, in the Choekhor Valley of Bumthang, were built to pin down the demoness’s left foot and left knee, respectively, and remain sites of pilgrimage more than a millennium later. Jambey Lhakhang is mentioned in 1355 by Longchenpa in a eulogy to the Bumthang valley as a place free of malignant spirits, and able to exert influence on other places, as acupuncture acts on the body, where Buddhist monuments should be built (

Aris 1979, pp. 5–6). Aris suggests that the construction of the outlying temples in the geomantric arrangement in some way ‘activated’ the site of Samye, where the first Tibetan monastery would be built roughly a century later, established by Trisong Detsen in c. 779 (

Aris 1979, p. 6). In this way, the construction of the ‘satellite’ monasteries to pin down the demoness represents an initiation of the work of conversion completed with the construction of the Samye monastery, bringing a greater swath of the Himalaya and Tibetan Plateau into the fold of Buddhism.

The story of Songtsen Gampo can be seen as an origin story of Bhutan, and shows that from its very earliest foundations—even before there was a geographical entity identified as Bhutan—politics, religion, territory, and landscape were closely linked, and interpenetrated one another. There is no origin story of Bhutan without Buddhism, without the arrival of a great saint from elsewhere, without the saint’s particular work on specific places in the landscape that later came to define the territory of Bhutan and extend into present-day Bhutan. These locations then serve as focal points for pilgrimage, prayer, and contemplation over centuries, binding the Bhutanese habits and practices to particular places, and receiving the empowerment that repeated prayer and pilgrimage pour into these places.

4. Guru Rimpoche and the Conversion of Local Deities

In the Buddhist Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau, spirits and deities have been understood to dwell in specific places on the landscape—ranging from rocks and trees to rivers, cliffs, and entire mountains, the sky above and underground—for at least a millennium (

de Nebesky-Wojkowitz 1975;

Samuel 1993;

Blondeau 1994;

Pommaret 1996;

Huber 1999). About a century after the construction of the temples, Padmasambhava, known throughout the Himalayas as Guru Rimpoche, or “Precious Teacher”, arrived in Bhutan. A Buddhist master within the Nyingma school, Guru Rimpoche is revered throughout the Himalayan region as a “second Buddha”. His eighth and ninth century travels and meditations throughout Bhutan caused the landscape to be marked with sacred sites. Guru Rimpoche subjugated eight classes of local spirits, believed to be the original owners of the land, and made them sworn protectors of the Buddha Dharma.

Like the construction of the temples by Songtsen Gampo, the visits of Guru Rimpoche are shrouded in legend and myth. Textual and oral sources offer various accounts of when and why Guru Rimpoche visited Bhutan. One popular oral tradition holds that Guru Rimpoche introduced Buddhism to Bhutan, arriving 747 C.E. on the back of a flying tiger, a manifestation his consort Yeshe Tsogyal, had taken to facilitate his access to a cave high above the Paro Valley. Guru Rimpoche entered into meditation in a cave at the site that, nearly a millennium later, in 1692, would become Taktsang Lhakhang, or Tiger’s Nest, a temple clinging to a cliff wall 3000 feet above the Paro valley.

Another version, recounted in

terma (hidden treasure text, Tib.:

gter ma) containing the life story of Yeshe Tsogyal, a historical figure as well as an enlightened being who had taken perceptible form, describes the tigress as a transformation of Trashi Kyidren, Guru Rimpoche’s ‘liberation consort.’ The Guru, as Dorji Drolō, united with Yeshe Tshogyal in the form of Ekadzati. In this state of union, Guru Rimpoche subjugated Tibet and “its four surrounding regions, along with all the gods and spirits of a million universes” (

Changchub and Nyingpo 1999, p. 96). The Guru projected innumerable ferocious emanations of himself, one of which—Blue-Black Vajrakila—landed at Paro Taktsang and subdued and converted “all the gods and mamos, demons and the eight classes of spirits in the lands of Mön,

5 Nepal, India, and other savage regions to the south” (

Changchub and Nyingpo 1999, p. 96).

Padmasambhava means “lotus born”: the future Guru Rimpoche is described as a self-born emanation of the Buddha Amitaba sent as comfort for sentient beings after the death of the historical Buddha (

Phuntsho 2013, p. 86). The lotus-born child was taken to King Indrabodhi of Oddiyana where he was given the name Tshokye Dorji and brought up as a prince, like the historical Buddha. Wishing to renounce the princely life, he engaged in outrageous behavior that led to his being banished from the kingdom. He wandered through north India, practicing esoteric spiritual techniques. As he received spiritual teachings from various teachers and developed a range of esoteric skills, he adopted various names, representing different stages of his life. Eventually, he was invited to Tibet to assist in the conversion of Tibet to Buddhism, through subjugation of the hostile spirits. In the wrathful form Dorji Drolō, Padmasambhava subdued the local deities of the Himalayas, creating a ground for Buddhism to spread (

Phuntsho 2013, pp. 88–89).

The

terma treasure text revealed by Ugyen Zangpo has become the dominant story of Guru Rimpoche’s arrival in Bhutan (

Phuntsho 2013, p. 94). In this account, King Sindhu Raja, who has fled India for Bumthang in central Bhutan, falls into a dispute with King Nawoche, and stops worshipping the tutelary deities. The deities extract their revenge by stealing his life essence (Tib.:

bla), and the king falls ill. Guru Rimpoche is summoned in approximately 810 CE (

Dorji 2016), and offered anything he wishes if he can retrieve the life essence and restore the king’s health. Guru Rimpoche wishes for a consort with whom he can carry out his spiritual practice. He enters into a seven-day meditation at the Dorji Tsegpa cliff, the home of the local guardian deity Shelging Karpo, the king of the deities. The intensity of Guru Rimpoche’s meditation leaves a body print in the cave. Guru Rimpoche creates a spectacle that draws Shelging Karpo near, and then subjugates him. Shelging Karpo returns the life essence to Guru Rimpoche, with a reprimand for the king’s negative actions and an admonition to behave properly in the future. Guru Rimpoche returns the life essence to the king, who is healed and hosts a celebration (

Phuntsho 2013, pp. 94–96). This story shows the mediating role of Buddhism in relation to deities of the landscape, as well as the deities’ continued unpredictable power expressed in the warning to “behave properly”. Following the king’s recovery, Guru Rimpoche invites both kings to the border of Mön and India, where he offers Buddhist teachings and the kings swear to live in peace. In the process of resolving this dispute, Guru Rimpoche introduced a system of legal principles into the land (

Dorji 2016). A stone pillar marks this site, a sacred site of pilgrimage, today known as Nabji Korphu (“the open ground of oath”), in Zhemgang in central Bhutan.

5. Green Guru Rimpoche: Environmental Avatar

Accounts of Guru Rimpoche’s travels in the Himalayas reveal four significant dynamics linking Vajrayana Buddhism and autochthonous deities with the landscape. The importance of these concepts and practices in maintaining the spiritual and ecological qualities of the landscape of Bhutan suggest that Guru Rimpoche could be considered a “green saint” of the Nyingma school of Vajrayana Buddhism.

First, the stories of Guru Rimpoche’s visits to Bhutan and throughout the Himalayas are recounted in hidden treasure texts known as

terma. These religious treasures, which also include religious objects, such as statues, bells, and daggers, and medicinal substances, were hidden for the benefit of future followers by great Buddhist teachers at the height of the Tibetan Yarlung dynasty, between the seventh and ninth centuries, C.E., in the soil, rocks, lakes, cliffs, mountains, statues, and other places, to be retrieved by designated “treasure revealers” known as

terton (Tib.:

gter ston) at appropriate later times (

Doctor 2005). The

terton, with an attitude of “constant mindfulness and deep reverence”, uses the habits of mind developed through spiritual practice to tune in to the signs and omens of this living landscape that point to the location of the hidden treasure (

Tshewang et al. 1995, p. 13). As followers of the Nyingma school revealed many of these hidden treasures emphasizing Guru Rimpoche’s spiritual feats in Tibet, his stature grew even greater (

Doctor 2005). The

terma ensure that the doctrines of Buddhism did not fade away or become muddled by mistaken interpretations but are continually enlivened with fresh revelations (

Rinpoche 1997). Through the continuing revelation of sacred texts and objects, the Nyingma school of Vajrayana Buddhism maintains it vibrancy and continuing relevance (

Karmay 2005).

Yeshe Tsogyal, whose life story was recorded in a

terma discovered by the terton Taksham Samten Lingpa living in the mid 17th century, was responsible for recording and concealing many of the treasures (

Changchub and Nyingpo 1999, p. xxxvi).

Terma are often discovered in natural features such as caves, lakes, and cliffs, as well as the air and the “‘netlike’ fabric of phenomena” (

Changchub and Nyingpo 1999, p. xxxvi). The secreting of sacred treasures throughout the landscape implies that the entire landscape is sacred and worthy of consideration. As Yeshe Tsogyal recounts the secreting of

terma- And not a single clod of earth that hands may grasp

- Is now without my blessing,

- And time the truth of this will show—

- The proof will be the taking out of Treasures.

- In lesser sites, so many that the mind cannot encompass,

- The imprints of my hands and feet now fill the rocks. …

- The fivefold elements were brought beneath my sway,

- And everywhere I filled the earth with Treasures.

While the legitimacy of these spiritual treasures has engendered debate (

Doctor 2005;

Gyatso 1993), that need not reduce their significance for followers of the tradition, or for the landscape of the Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau. That any bit of terrain may reveal profound sacred insights suggests that the entire landscape is worthy of respect as a holder of these sacred treasures. Furthermore, no particular locality should be prized over, or exhibit hegemony over, any other area with regard to

terma (

Kapstein 2000). Although average people are not in possession of the spiritual skills required to locate and produce these treasures, they may adopt a reverent attitude for the terrain that disgorges these sacred relics.

Second,

beyul (Tib.:

sbas yul) are sacred hidden valleys, existing on both the material and spiritual levels, hidden by Guru Rimpoche throughout the Himalayas, as sites of refuge for Buddhists in future times of catastrophe and persecution (

Chettri et al. 2007;

Lohani n.d.;

Sherpa 2005). Beyond their physical manifestation, the

beyul have sacred and celestial aspects accessible only to the spiritually accomplished. According to tradition,

beyul are protected by secret doors, accessible only to adepts, that will open at the appropriate time, transporting practitioners to another realm of existence. Some well-known

beyul are currently existing geographical places, including the Khumbu, Kembalung, and Rowaling valleys of Nepal (

Skog 2016;

Spoon and Sherpa 2008;

Armbrecht 2009); Pemako in southeastern China (

Baker 2004;

Sherpa 2005); the Bumthang valley of Bhutan (

Tshewang et al. 1995); and Dremoshung, an area below Mount Kangchenjunga in Sikkim (

Balikci Denjongpa 2002;

Ramakrishnan 1996;

Sherpa 2005). The

beyul are believed to supply material abundance to meet human needs; people are expected to behave in a manner appropriate to a sacred space. The

beyul concept implies both an imputation of sacredness of the landscape by a great teacher, and a recognition that sacred landscapes could provide refuge for Buddhist practitioners in times of trouble. In contemporary times, the

beyul concept has been adapted and adopted to support biocultural conservation, and has been applied to the Khumbu region of Nepal (

Skog 2016;

Spoon and Sherpa 2008) and the Bumthang valley of Bhutan (

Tshewang et al. 1995).

Third, Guru Rimpoche imputed sanctity into the landscape through travels and meditation at various natural and built places, including caves and meditation huts built into cliff walls, which continue to be sacred pilgrimage sites for thousands of followers a millennium later.

6 His footprints and body imprints sacralize the rocks and caves where he meditated, including such sites as Paro Taktsang, in western Bhutan, and a cave near Gom Kora, a large temple in eastern Bhutan, among many other sites.

Fourth, the accounts of Guru Rimpoche’s visits demonstrate the intertwining of Buddhism and pre-Buddhist deities and spirits throughout Bhutan. Guru Rimpoche’s conversion of the autochthonous landscape deities to sworn protectors of the Dharma intimately connects Buddhism with these landscape deities, and embeds Buddhism in the landscape. As Guru Rimpoche subjugated Shelging Karpo, king of the deities, the deities are understood to have come under the sway of Buddhism, and to have become sworn protectors of Buddhism. From the very earliest days of Buddhism in Bhutan, local deities and spirits were converted to the Dharma, and incorporated as pantheon of worldly deities and spirits (Tib.: ’jig rten pa’i srung ma). These “mundane” deities inhabit the six realms of samsara, the continual cycle of death and rebirth in the Buddhist tradition, unlike the enlightened deities of the Buddhist meditational realms.

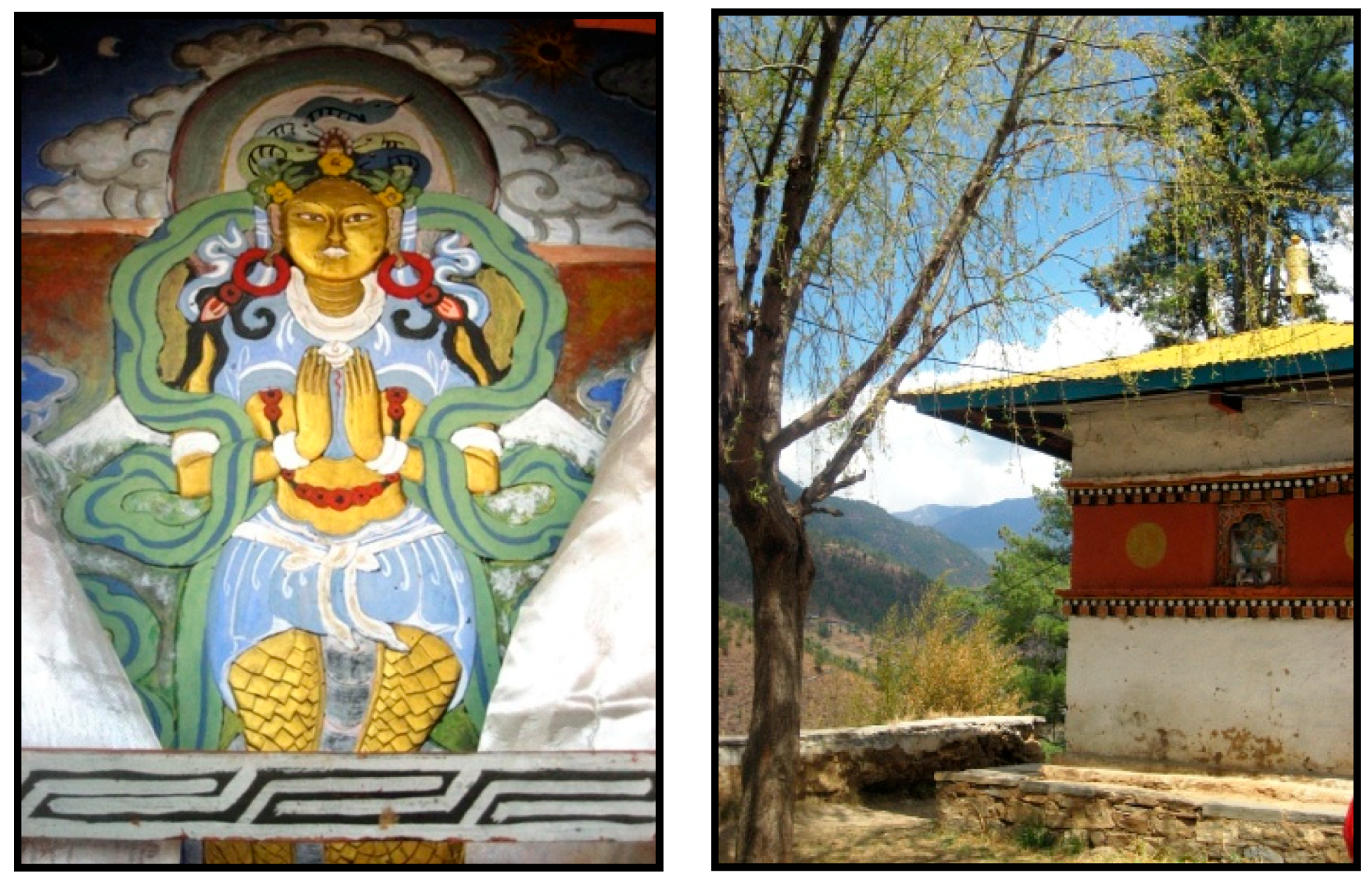

The incorporation of worldly deities with Buddhism is such that images of deities can be found in monasteries and temples. An image of the territorial deity can often be found in either in the

goenkhang (the chapel of fierce protectors, a space in which women are not allowed) or in a special shrine near the main altar. The incorporation of pre-Buddhist deities in the local Buddhist temples (Dz.:

lha khang; literally “god house”) incorporate the local deities into the vernacular practice and ritual of Buddhism. For example, at Dechen Phodrang Monastic School in Thimphu, images of the local

lu (Dz./Tib.:

klu) spirit can be found on a chorten outside the monastery (see

Figure 1). While the

lu spirits were subjugated by Guru Rimpoche, they were not expelled but persisted under the power of Buddhism (cf.

Mills 2007).

6. Local Deities and Landscape Perceptions

Worldly deities and spirits are closely associated with particular places on the landscape such as forest patches, as well as rocks, cliffs, lakes, river bends, and water springs understood to be their abodes. The

neypo (Dz./Tib.:

gnas po) is the “host” or owner of a place. Likewise, the

neydak (Dz./Tib.:

gnas bdag) is the guardian of a sacred site or

ney (Dz./Tib.:

gnas). The

neydak and

yul lha (Dz./Tib.

yul lha), who is the “country god”, are sometimes conflated. The

sadak (Tib.:

sa bdag), inhabiting large trees and rocks, is the “lord of the soil” and must be propitiated with incense to prevent landslides (

Giri 2004). The

keyla (Dz./Tib.:

skye lha), the deity of the birthplace, is a protector deity.

7 Contrasting worldly deities with those enlightened beings that may be visualized during meditation, Dasho Karma Ura, a leading historian and researcher of Bhutan, has argued that the pragmatic focus of worldly deities leads them to have a “pronounced environmental significance in mediating between resources and people” (

Ura 2001b). This form of engagement is what the Himalayanist Geoffrey Samuel has termed the “shamanic form” of Buddhism which focuses on worldly prosperity and protection from misfortune.

Within this worldview, the moral valence of human actions affects the quality of the landscape. Certain activities create moral or material pollution, known as

drib (Tib.:

sgrib or

grib), which offends local deities. An accumulation of

drib, which increases susceptibility of illness or misfortune, can result from many daily activities, including attending a birth or death; using garlic, eggs, and other ‘strong’ foods; and cooking or burning meat, particularly in inappropriate places, such as near lakes or on high mountain passes. For this reason, protector deities, such as the

yul lha8 (“country god”) and

tsen, who oversee entire valleys or regions, reside high in the mountains where they remain aloof from the spiritual and physical pollution of human activities below (see

Figure 2). In the literary tradition, the mountain deity overseeing a local area has a parental relationship to the people living below (

Karmay 1998). The

yul lha or territorial deity is petitioned at each phase of the agricultural cycle for boons and protection of crops in some villages (

Pommaret 2004). Deities offended by the accumulation of pollution will retaliate with destructive weather, untimely rain, landslides, and illness.

Worldly deities and spirits are accorded significant deference in villagers’ daily lives because of their perceived ability to grant blessings in the form of abundant harvests, timely rain, and freedom from misfortune and disease. Illness and misfortune, as interpreted through the lens of previous experience as well as consultation with a pawo, a spiritual-magical healer, or a tsipa, an astrologer, are understood to result from contravening the deities’ wishes. In my fieldwork, several well-educated interlocutors who were well familiar with scientific explanations, offered stories of occasions when they had succumbed to mysterious maladies, untreatable by biomedical interventions. Only when they consulted a tsipa and learned that they had offended a lu—a subterranean spirit associated with prosperity and the maintenance of hierarchy, which can be easily offended by ritual or material pollution—were they able to make appropriate oblations to the lu and regain their health. The lu is a water spirit similar to the Indian nāga that influences abundance when well-placated but can cause treatment-resistant rashes and boils when displeased. The lu resides in water sources, such as springs and seeps, requiring that its abode be kept free of contamination, including human waste. A well-placated lu will ensure bountiful harvests and other good fortune for the family who provides appropriate offerings and maintains its habitat properly.

Deities and spirits influence the use of natural resources through a variety of geographical and temporal prohibitions that shape human behavior and contribute to biocultural resilience. For example, temporal prohibitions require the ‘closure’ of mountain peaks during spring and summer to maintain the favor of protector deities. The period of closure coincides with the season of maximum plant growth, allowing herbs to grow and trees to leaf out undisturbed by humans (

Allison 2004). The

tsen of eastern Bhutan requires that the high reaches of its mountains be ‘closed’ to human presence and especially timber and bamboo harvesting at certain times of the year, a period known as

ladam or

reedum (

Allison 2004,

2015;

Giri 2004;

Kuyakanon and Gyeltshen 2017). In their detailed analysis of one such

ladam closure preceded by a ritual “to petition Khobla Tsen [the

tsen protector deity] for his protection and to remind him of his obligations to the community”,

Kuyakanon and Gyeltshen (

2017, p. 17) highlight the place-based nature of the ritual, and observe that the ritual responds to specific community concerns, to support “community and livelihood maintenance”. They further observe that the ritual and subsequent mountain closure or “sealing” has a role in village political ecology through “regulating seasonal human-livestock movement and activities” and prohibiting the collection of forest products and the entry of people not recognized as being from the village (

Kuyakanon and Gyeltshen 2017, p. 18).

7. Spiritual Beliefs, Government Policy, and Local Development

Local spiritual beliefs are central to the cultural identity of the Kingdom, making their way into the Constitution (

RGOB (

Royal Government of Bhutan)

2008), government planning documents (

RGOB (

Royal Government of Bhutan)

1998,

1999), and town planning and construction negotiations. The Bhutanese government has recognized the value of traditional cultural beliefs, incorporating them into environmental research, policy, and planning. For example, the 1995 Forest and Nature Conservation Act (

RGOB (

Royal Government of Bhutan)

1995), which prioritized conservation, sought to reinvigorate local forest management institutions and highlighted the rights of communities to manage forests for traditional uses such as

sokshing (leaf litter collection) and

tsamdro (pastureland) (

Tshering 2006, p. 76).

The Bhutanese Constitution, adopted in 2008, identifies Buddhism, which “promotes the principles and values of peace, non-violence, compassion and tolerance”, as the “spiritual heritage” of Bhutan (

RGOB (

Royal Government of Bhutan)

2008, p. 9).

9 The importance of Buddhism to the culture of Bhutan is further explicated in Article 4 of the constitution, Culture, which requires the State to “endeavour to preserve, protect and promote” places like

lhakhang10 (Buddhist temples; Tib./Dz.:

lha khang) and

nye (sacred sites; Tib./Dz.:

gnas).

Nye sacred sites are generally associated with Guru Rimpoche: places where he subdued demons and converted them to Buddhism, produced holy water, or mediated.

Deity beliefs and practices are referenced in national government documents, such as

Bhutan 2020 (

RGOB (

Royal Government of Bhutan)

1999). Citing historical “formal and informal rules and norms” that teach people to “interpret nature as a living system in which we are part”, Bhutanese government documents reinforce a perspective that views natural ecosystems as lively and animated, and not as simply stores of material natural resources awaiting human use (

RGOB (

Royal Government of Bhutan)

1998,

1999). The Foreword to

The Middle Path: National Environment Strategy for Bhutan (

RGOB (

Royal Government of Bhutan)

1998), begins by identifying the ancient relationship between people and their environment.

Traditional and local beliefs promoted the conservation of the environment, and key ecological areas were recognized as the abodes of gods, goddesses, protective deities and mountain, river, forest and underworld spirits. Disturbance or pollution of these sites would result in death, disease or famine. Buddhism and animism reinforced this traditional conservation ethic and promoted values such as respect for all forms of life and giving back to the Earth what one has taken away. This traditional respect for the natural world ensured that Bhutan emerged into the 20th century with an intact natural resource base.

(p. 12)

This text cites Buddhism and animism as central to the Bhutanese perception of nature, and as relevant to shaping Bhutanese perceptions of and interactions with nonhuman nature. In both reflecting an orientation toward nonhuman nature, and shaping the perception of nature, these documents construct a Bhutanese “environmental imaginary”, based on Buddhism and deity beliefs.

The Royal Society for the Protection of Nature, Bhutan’s first non-profit non-governmental environmental organization, established in 1987, noted in the Foreword to its

Buddhism and the Environment publication, “Even today, mountains, lakes, rivers, streams and rocky cliffs are respected by communities as abodes of spirits and deities and remain free from human contact and pollution” (

RSPN (

Royal Society for Protection of Nature)

2006, no page given). The book notes that the deities “are there to help you in this lifetime only” (i.e., they are not to be conflated with tutelary deities that “help you in attaining enlightenment” (

RSPN (

Royal Society for Protection of Nature)

2006, p. 24)), and describes the interaction of deities of landscape with humans:

… [t]he trees have tree deities, the stones have stone deities and the earth has earth deities. These deities have to be respected and left to themselves. In the event that a tree is cut down for no reason, it amounts to destroying their dwelling and the deity in turn is believed to bring harm to the person responsible for such an act, his family or the whole village. There will be lack of rain, when it is most wanted. The crops will dry up or get destroyed by hailstorms causing famine. There will be widespread diseases, leading to both human and animal deaths.

The book derives a didactic message from the possibility of deity-induced calamities, proffering the injunction: “[a]s Buddhists, we must at all costs try to avoid cutting down trees or carrying out any activity that has a wrong bearing on the mother earth” (

RSPN (

Royal Society for Protection of Nature)

2006, p. 25).

Concern about the negative repercussions from wrathful deities has, at times, generated contention around the relative priority of infrastructure development as compared with religious and spiritual preservation. Local resistance can slow or divert building or road construction. Government officials endeavor to incorporate viewpoints from all relevant stakeholders before projects commence. Bhutan’s environmental assessment process requires the identification of any “religious site or archaeological site” near proposed construction, and necessitates the engagement of the National Commission for Cultural Affairs in cases where a proposed project is proximate to a religious site. In the mid-1990s, the course of a feeder road to Shingkhar in the Ura region of Bumthang was changed to avoid the citadel of the territorial deity (

Pommaret 2004, p. 49). In 2007, a town planner described a situation in Mongar district in which local people objected to a provision in a town development plan. She said,

People didn’t want the area to be developed because they thought there was a ghost in the area. I think we took it up anyway. There was some resistance from that side. They said, ‘we are not supposed to touch this area.’ In some cases, we have to respect that viewpoint because it is the sentiment of the people. If there are alternatives, we try to check into them. It might not have been Mongar, but somewhere in the east …”.

(interview with the author, 26 September 2007, Thimphu)

A British foreign development consultant described to me a situation in the Trongsa district in which local people objected to a retaining wall that was to be built near a big tree inhabited by a spirit. Many of the workers fell sick, and a lama was summoned to perform a ceremony. While the hospital and retaining wall were built, local people continue to conduct ceremonies to appease the spirit (interview with the author, 26 September 2007, Thimphu).

In some cases, local resistance is seen as strategic deployment of spiritual beliefs. A road contractor pointed out that builders and government officials seek to include information about spiritually sensitive places in the mandatory environmental examination, which asks for information about religious and heritage sites near the proposed project, provided to the National Environment Commission. Often such information is not provided at the time of the assessment: “Only later, when the road building commences, people come out and complain that the road is going through a spirit’s place”, he said (interview with the author, 28 September 2007, Thimphu).

Even when sacred sites are identified in advance, conflicts with material and economic development may arise. Villagers in Merak, eastern Bhutan, petitioned the local government to stop construction of a parking space that was harming a sacred stone (Dz./Tib.:

gnas rdo) (

Tshedup 2018). According to the complaint, the Department of Culture had previously identified the area as a sacred site and restricted development there, but a local official proceeded with enlarging a parking lot. Villagers were concerned about damage to the sacred stones of Aum Jomo, the local deity (

Tshedup 2018). Such cases show the continuing relevance of deities for local peoples and their role in defining sacred place, while highlighting the contested discursive space of sacred places.

These instances reveal the material and discursive tension inherent in maintaining a relational ontology that recognizes agency in a range of beings and landscapes in a world increasingly dominated by the values of materialist efficiency. While the Bhutanese government seeks to improve material well-being through the extension of roads and the construction of hospitals and other facilities—as desired by many rural people—its efforts are sometimes thwarted by local perceptions of sacred sites or deities’ demands. While these objections are sometimes characterized as superstitious and “backward” resistance to material progress, they are highlighted here as important expressions of a value system that prioritizes values beyond the material and efficient. In contemporary globalized neoliberal capitalism, such values are often discounted or ignored. The Bhutanese case points to the continuing significance of these values, as well as the challenges of negotiating such values with material, economic, and infrastructure development.