The Fulcrum of Experience in Indian Yoga and Possession Trance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Antaḥkaraṇa

“assigns the tasks of perception, cognition, recollection, and others to an entity conceived as the “inner instrument” (antaḥkaraṇa), [which] includes the mind (manas) manifesting attentivity, the intellect (buddhi) meaning the capacity for determination and ascertainment, and citta, a storehouse of past impressions and memories. The inner instrument is a crucial aspect of the embodied person that coordinates the functions of the senses and the body while in constant interaction with events within the body and its surroundings. The inner instrument is said to “reach out” to objects in the environment through the senses, and to become transformed into their shapes, so to speak. The inner instrument is constantly undergoing modifications, depending on the objects it reaches out to, and it tries to ‘know’ them by itself being transformed into their shapes.”

3. Saṃyama

4. Possession

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

Primary Sources

- Antantaḥkaraṇaprabodha with Five Sanskrit Commentaries. Edited by Gosvāmī Śyām Manohar. Baroda: Śrī Kalyāṇarāyajī kī Havelī, Saṃ. 2036 (1979).

- Nṛsiṃhalāljī-Ṣoḍaśgranth. 1970. Gosvāmī Śrīnṛsiṃhalāljī Mahārāj kṛt Brajbhāṣā ṭīkā sahita. Mumbai: Śeṭh Nārāyaṇdās aur Śeṭh Jeṭhānand Āsanmal Ṭrast, pp. 108–21.

- Tāntrikābhidhānakośa, vol. 1: A-AU [vowels]. By Helene Brunner, Gerhard Oberhammer, André Padoux, et al. Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, phil.-hist. Kl., Sitzungsberichte, vol. 681. Vienna: Verlag der Österreischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1999.

- Tattvārthadīpanibandha (saprakāśaḥ): Śāstrārtha-Sarvanirṇaya-rūpa-prakaraṇa-dvayopetaḥ. Edited by Gosvāmī Śyām Manohar. Kolhapur: Śrī Vallabhavidyāpīṭha-Śrīviṭṭhaleśaprabhucaraṇāśrama Trust, Saṃ. 2039 (1982).

Secondary Sources

- Aaltonen, Jouko. 2000. Kusum. Illume Co. Helsinki, 69 minutes. Available online: https://search-alexanderstreet-com.proxy.lib.uiowa.edu/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cvideo_work%7C1879379 (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Acri, Andrea. 2012. Yogasūtra 1.10, 1.21-23, and 2.9 in the Light of the Indo-Javanese Dharma Pātañjala. Journal of Indian Philosophy 40: 259–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, Andrew. 2018. Recasting Lok and Folk in Uttarakhand: Etymologies, Religion and Regional Musical Practice. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 41: 483–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, Ram Prasad, Heinz Werner Wessler, and Claus Peter Zoller. 2014. Fairy lore in the high Himalaya Mountains of South Asia and the hymn of the Garhwali fairy ‘Daughter of the Hills’. Acta Orientalia 75: 79–166. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki, Loriliai. 2014. A Cognitive Science View of Abhinavagupta’s Understanding of Consciousness. Religions 5: 767–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardeña, Etzel. 1994. The domain of dissociation. In Dissociation. Clinical and Theoretical Perspectives. Edited by S. J. Lynn and J. Rhue. New York: Guilford, pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chapple, Christopher. 2008. Yoga and the Luminous: Patañjali’s Spiritual Path to Freedom. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, Graham. 1999. Healing and the Transformation of Self in Exorcism at a Hindu Shrine in Rajasthan. Social Analysis 43: 108–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, Graham. 2003. The Divine and the Demonic: Supernatural Affliction and Its Treatment in North India. London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon. [Google Scholar]

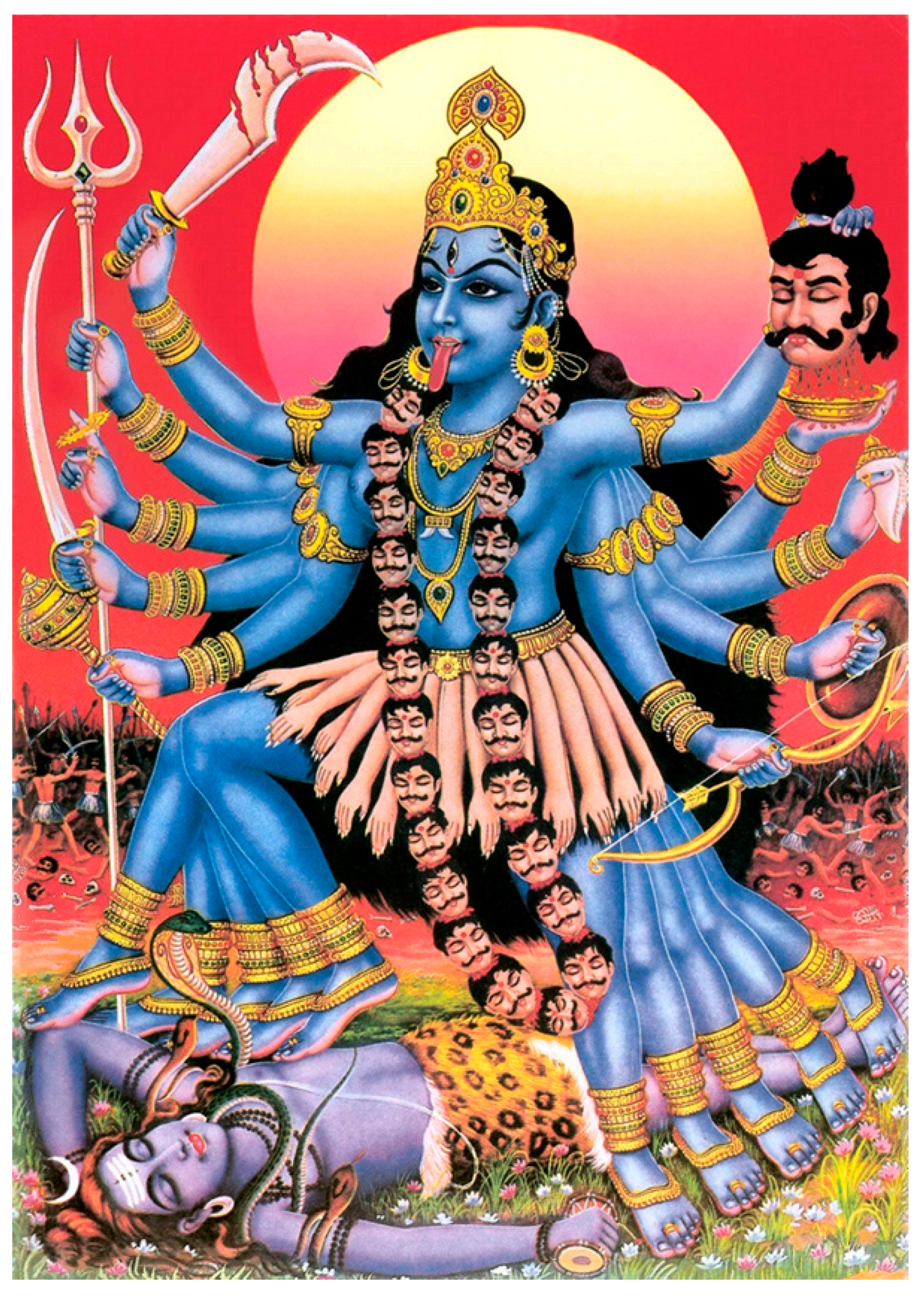

- Erndl, Kathleen M. 1993. Victory to the Mother: The Hindu Goddess of Northwest India in Myth, Ritual, and Symbol. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario, Alberta. 2015. Grace in Degrees: Śaktipāta, Devotion, and Religious Authority in the Śaivism of Abhinavagupta. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Elaine M. 2017. Hindu Pluralism: Religion and the Public Sphere in Early Modern South India. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, J. Richardson. 1993. Performing Possession: Ritual and Consciousness in the Teyyam Complex of Northern Kerala. In Flags of Flame: Studies in South Asian Folk Culture. Edited by Heidrun Brückner, Lothar Lutze and Aditya Malik. New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 109–38. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, J. Richardson. 1998. Formalized Possession Among the Tantris and Teyyams of Malabar. South Asia Research 18: 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freschi, Elisa. 2012. Duty, Language and Exegesis in Prābhākara Mīmāṃsā. Including an Edition and Translation of Rāmānujācārya’s Tantrarahasya, Śāstraprameyapariccheda. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Gokhale, Pradeep. 2015. Interplay of Sāṅkhya and Buddhist Ideas in the Yoga of Patañjali (With Special Reference to Yogasūtra and Yogabhāṣya). Journal of Buddhist Studies 12: 107–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hiltebeitel, Alf. 1991. The Cult of Draupadī. Vol. 2: On Hindu Ritual and the Goddess. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

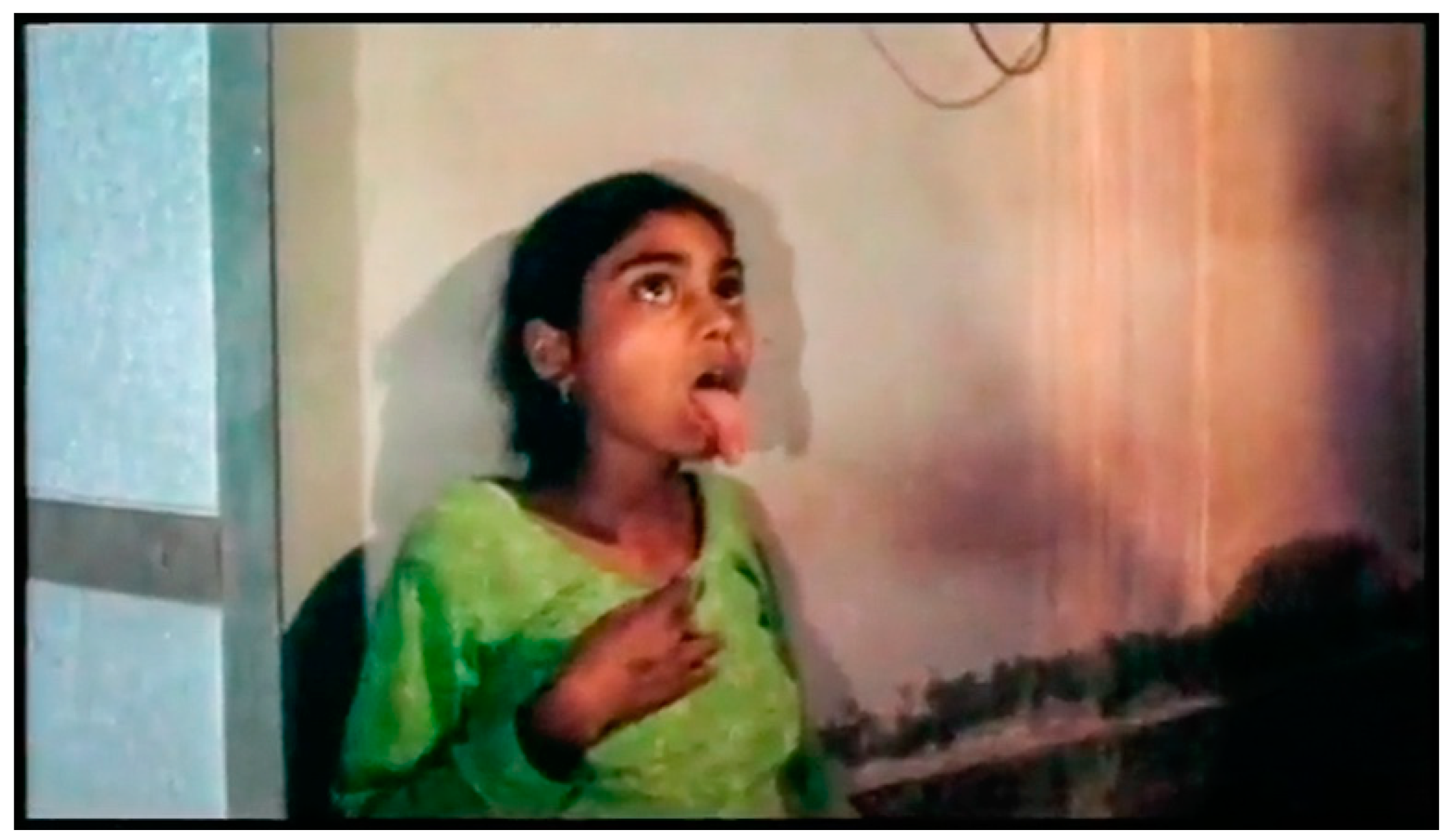

- Kusum. 2000. Produced and directed by Jouko Aaltonen. London: Royal Anthropological Institute.

- Larson, Gerald James, and Ram Shankar Bhattacharya. 1987. Sāṁkhya: A Dualist Tradition in Indian Philosophy. Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies. Edited by Karl Potter. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol.4. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 1996. On actor-network theory: A few clarifications. Soziale Welt 47: 369–81. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, Philipp A. 2006. Samādhipāda. Das erste Kapitel des Pātañjalayogaśāstra zum ersten Mal kritisch ediert. Aachen: Shaker. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, Philipp A. 2010. On the Written Transmission of the Pātañalayogaśāstra. In From Vasubandhu to Caitanya. Studies in Indian Philosophy and its Textual History. Edited by Johannes Bronkhorst and Karin Preisendanz. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 157–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson, James. 2011. Nāth Sampradāya. In Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. III. Edited by Knut A. Jacobsen, Helene Basu, Angelika Malinar and Vasudha Narayanan. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson, James. 2012. Siddhi an Mahāsiddhi in Early Haṭhayoga. In Yoga Powers. Extraordinary Capacities Attained through Meditation and Concentration. Edited by Knut A. Jacobsen. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 327–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson, James. 2016. The Amṛtasiddhi: Haṭhayoga’s Tantric Buddhist Source Text. Draft of Paper to be Published in a festschrift for Professor Alexis Sanderson. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson, James, and Mark Singleton. 2017. Roots of Yoga. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, June. 2018. Lost Ecstasy: Its Decline and Transformation in Religion. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes, Walter. 2016. Is Viveka a Unique Pramāṇa in the Vivekacūdāmaṇi? Journal of Indian Philosophy 44: 155–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Barbara Stoler. 1998. Yoga: Discipline of Freedom: The Yoga Sūtra Attributed to Patañjali. New York: Bantam. [Google Scholar]

- Neki, J. S. 1973. Psychiatry in South-East Asia. British Journal of Psychiatry 123: 257–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeyesekere, Gananath. 1981. Medusa’s Hair: An Essay on Personal Symbols and Religious Experience. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pakaslahti, Antti. 1998. Family-Centered Treatment of Mental Health Problems at the Balaji Temple in Rajasthan. Studia Orientalia 84: 129–66. [Google Scholar]

- Paranjpe, Anand C. 1998. Self and Identity in Modern Psychology and Indian Thought. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Redington, James D. 2000. The Grace of Lord Krishna: The Sixteen Verse-Treatises [Ṣoḍaśagranthāḥ] of Vallabhacharya. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rouget, Gilbert. 1985. Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations between Music and Possession. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, William S. 1991. Mountain Goddess: Gender and Politics in a Himalayan Pilgrimage. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, William S. 1995. The Gods at Play: Līlā in South Asia. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, William S. 2002. Dancing the Self. Personhood and Performance in the Pāṇḍav Līlā of Garhwal. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, William S. 2009. God of Justice: Ritual Healing and Social Justice in the Central Himalayas. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D. D. 2006. Uttarakhand ke lok devatā. Haldwani: Ankit Prakashan. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D. D. 2012. Uttarākhaṇḍ gyānkoṣ (A Compendium of Uttarakhand Related Knowledge). Haldwani: Ankit Prakashan. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Frederick M. 1998. Nirodha and the Nirodhalakṣaṇa of Vallabhācārya. Journal of Indian Philosophy 26: 589–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Frederick M. 2006. The Self Possessed: Deity and Spirit Possession in South Asian literature and Civilization. New York: Columba University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Benjamin Richard. 2008. “With Heat Even Iron Will Bend”: Discipline and Authority in Ashtanga Yoga. In Yoga in the Modern World: Contemporary Perspectives. Edited by Mark Singleton and Jean Byrne. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Frederick M. 2010. Possession. Oxford Bibliography Online. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780195399318-0101. Available online: http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195399318/obo-9780195399318-0101.xml (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Smith, Frederick M. 2018. Gaṅgā Devī between Worlds: Her Annual Pilgrimage between Mukhba and Gangotri. South Asian Studies 34: 169–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, John M. 1977. Special Time, Special Power: The Fluidity of Power in a Popular Hindu Festival. Journal of Asian Studies 37: 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiessen, Gerd. 2014. Sarx, Soma, and the Transformative Pneuma: Personal Identity Endangered and Regained in Pauline Anthropology. In The Depth of the Human Person: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Edited by Michael Welker. Cambridge: Wm. B. Eerdmans, pp. 166–85. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudeva, Somadeva. 2011. Haṃsamiṭṭhu: ‘Pātañjalayoga is Nonsense’. Journal of Indian Philosophy 39: 123–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudeva, Somadeva. 2017. The Inarticulate Nymph and the Eloquent King. In Revisiting Abhijñānaśākuntalam: Love, Lineage and Language in Kālidāsa’s Nāṭaka. Edited by Saswati Sengupta and Deepika Tandon. Hyderabad: Orient Black Swan, pp. 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- White, David Gordon. 2004. Early Understandings of Yoga in the Light of Three Aphorisms from the Yoga Sūtra of Patañjali. In Du corps humain, au Carrefour de plusieurs saviors en Inde: Mèlanges offèrts à Arion Roşu par ses collègues et ses amis à l’occasion de son 80e anniversaire. Edited by Eugen Ciurtin. Paris: De Boccard, pp. 611–27. [Google Scholar]

- White, David Gordon. 2014. The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali: A Biography. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For a brief summary, see https://www.tuck.com/neurotransmitters/. |

| 2 | See her translation of YS 3.37 and 4.1, pp. 68 & 74, respectively. |

| 3 | This is the case even if Sāṃkhya metaphysics is entirely different from the other orthodox schools that obtained maximum currency as religious schools, namely the various expressions of Vedānta. Thus, Sāṃkhya cosmology, minus the nettlesome duality of prakṛti and puruṣa, nature and individual consciousness, was employed as the baseline explanation of the structure of the self in Ayurveda, virtually all sectarian Purāṇas, and most philosophical schools. Similarly, it is accepted at face value, which is to say in its Sāṃkhya embodiment, by Abhinavagupta, a term on which he does not speculate. It is absent from the Tāntrikābhidānakośa, which suggests that the Tantras paid scant attention to it; it was simply a structure designed to uphold the inner constitution. Thanks to Alberta Ferrario for pointing this out to me. It is interesting that the antaḥkaraṇa barely plays a role in Abhinavagupta’s discourse on śaktipāta (Tantrāloka, chapter 13), which brings about the kinds of transitional experience discussed below (Ferrario 2015). |

| 4 | Loriliai Biernacki writes: “Known as the antaḥkāraṇa, the inward sense organs, these include the intellect (mahat/buddhi), the ego (ahaṁkāra), and the mind (manas). These three, as evolutes of Prakṛti, fundamentally lack sentience. Thus what a contemporary Western scientist might understand as “mind”, “awareness”, or ‘consciousness’, is, to the contrary, from an Indian perspective relegated to the level of mere materiality” (Biernacki 2014, p. 4). |

| 5 | The epistemological process here is well-described recently by Walter Menezes: “Knowledge arises when there is a modification (vṛtti) of antaḥkaraṇa in the form of the object, assisted by the instrumental cause (karaṇa). Thus, the same basic consciousness assumes various forms through different mental modes corresponding to different objects. This clarifies why there is knowledge of varied forms, such as, knowledge of a thing, e.g., tree, house, and horse; knowledge of an attribute, e.g., redness, beauty, and roundedness; and knowledge of action, e.g., flowing, flying, and blowing. Like the varied knowledge of external objects, there is also varied knowledge of mental states, such as happiness fear, love, imagination, memory, and so on, of which mind is also the instrumental cause. By taking various forms of diverse objects, antaḥkaraṇa causes variations in knowledge or consciousness, but does not generate it” (Menezes 2016, p. 157). Note that the term antaḥkaraṇa also entered the stream of non-philosophical Sanskrit. Kalidāsa used it in Abhijñānaśkuntalā 1.19: asamśayaṃ kṣatraparigrahakṣamā yad evam asyām abhilāṣi me manaḥ | satāṃ hi saṃdehapadeṣu vastuṣu pramāṇam antaḥkaraṇapravṛttayaḥ || “Doubtlessly she is fit to be wed by a warrior, since my heart [manaḥ] desires her so. For in matters of doubt the inclinations of their inner faculties [antaḥkaraṇa] are authority for the good” (Vasudeva 2017, p. 195). |

| 6 | For information on the Ṣoḍaśagranthāh, see (Smith 1998; Redington 2000). Redington has translated the Antaḥaraṇaprabodha along with a few textual notes and more extensive notes from his teacher, Shyam Manohar Goswamy from Mumbai. |

| 7 | Vallabhācārya and the commentarial tradition on his work speak of līlāvatāra, a broader extended realm of the Supreme Lord, which includes materiality as his līlā or divine play. In this reckoning the antaḥkaraṇa would be regarded as part of the whole fabric of līlā, neither external nor internal, but a mere facet of a whole in which its role as connective tissue is devalued. Much has been written on līlā; see, for example, (Sax 1995). |

| 8 | Somewhat analogous to this is Elaine Fisher’s quotation of Kumārasvāmin, a fifteenth century Śaivasiddhānta philosopher who has written a commentary on the Tattvaprakāśa of Bhojadeva: “For, unmediated [aparokṣabhūta] knowledge [jñāna], in fact, is the cause of su-preme beatitude [apavarga]. And its unmediated quality arises when the traces [saṃskāra] of ignorance [avidyā] have been concealed through intensive meditation [nididhyāsana]. And intensive meditation becomes possible when the knowledge of Śiva arises through listening to scripture [śravaṇa] and contemplation [manana]. And those arise because of the purification of the inner organ [antaḥkaraṇa]. That [purification] occurs through the practice of daily [nitya] and occasional [naimittika] ritual observance, with the abandoning of the forbidden volitional [kāmya] rituals” (Fisher 2017, p. 42). Again, the antaḥkaraṇa serves as a radio; it is a mechanism, a device with varying degrees of clarity or static, which mediates between a remote source and a listener. In a more modern context, note the words of the 20th century yogi Pattabhi Jois: “Sira [channel systems of the mind, otherwise labeled srotas] are those nāḍī [internal channels] that carry messages from the antaḥkaraṇa, a “message center” located in the region of the heart, throughout the body, and also provide a “vital link in the functioning of the sense organs” (Smith 2008, p. 10, fn. 11). |

| 9 | More could be said about this, particularly because the guiding forces of the antaḥkaraṇa in these two cases would be different. In the case of theistic saguṇa, it would be Supreme Lord (puruṣottama), while in the nondual nirguṇa case the antaḥkaraṇa would be guided more by the interior dynamic between the self or ātman and its conscious positioning with the abstract absolute, the brahman. To say more would require a separate essay. |

| 10 | (Maas 2006, 2010), and elsewhere, settles this debate. He also argues, from manuscript sources, that the YS was composed in its entirety by Vyāsa, the first commentator on the YS. Many questions can be raised about this assertion, but this is not the place for it. However, this is why efforts such as Chapple’s essay “Reading Patañjali Without Vyāsa” remain valuable (Chapple 2008, pp. 219–35). Other reasons for keeping the debate alive are found in (Acri 2012; Gokhale 2015). |

| 11 | Namely the vṛttis, waves or mental modifications that must be evened out through the practice of yoga (YS 1.5-1.11), obstacles (antarāya) to our practice (YS 1.29-1.40), and (3) afflictions (kleśa) with which we must all deal (YS 3.3-3.14). |

| 12 | Many of the tantric and yoga texts list eight characteristic siddhis: aṇimā (reducing the size of the body to molecular dimensions), mahimā (expanding the size of the body to enormous dimensions), garimā (heaviness, increasing the body weight), laghimā (becoming light as a feather), prāpti (ability to translocate), prākāmya (ability to acquire whatever is desired), iṣitvā (lordship), and vaśitvā (ability to control nature). These are referred to in YS 3.45, but are not listed. Indeed, this sūtra should serve as the link between the siddhis mentioned in YS and the array of later texts. Many more than these are found in the later texts, although nowhere are they explicitly tethered to the process discussed in the YS. It is not certain that the later yoga texts thought about siddhis as actualized through the same process or explanation discussed in the YS, namely through saṃyama as the stable collocation of dharāṇa, dhyāna, and samādhi, but the conceptual link leaves space for this to have been carried forward. |

| 13 | See (Mallinson 2012) and elsewhere. This is now acknowledged in the academic study of yoga. See (Vasudeva 2011) for an eighteenth century example of the early goals of yoga as articulated in the YS later on losing their dualist focus as yoga is appropriated into the realm of Vedānta. |

| 14 | All translations and editions of the YS (or PYŚ, as it’s commonly called now, for Pātañjalayogaśāstra, (cf. Maas 2006) must perforce address the topic of siddhis, but the treatments are usually briefly, with almost no learned elucidation. The infrequency of the term outside the YS may be seen in its treatment by Mallinson and Singleton (2017, pp. 286–87, 324) and Larson and Bhattacharya, where it is rarely referred to outside the YS and its commentaries. Larson and Bhattacharya present the commentarial discussions (see their index), even if they are difficult to follow due to the policy of the Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophy to include minimal Sanskrit. Precedents, however, this may be seen in the Bhagavadgītā. Cf. BhG 4.26 śrotrādīnīndriyāṇy anye saṃỵamāgniṣu juhvati—One should offer senses such as hearing and others into the fires of saṃyama, viz. self-control); 2.61 (tāni sarvāṇi saṃyamya yukta āsīta matparaḥ—with the senses restrained, he should sit, disciplined focused on me); 3.6 (karmendriyāṇi saṃyamya ya āste manasā smaran—he sits, restraining his organs of action); 6.14 (manaḥ saṃyamya maccitto yukta āsīta matparaḥ—the mind restrained, collected together, etc.), 8.12 (sarvadvārāṇi saṃyamya mano hṛdi nirudhya ca—having restrained all the gates [orifices], confining the mind in the heart). These passages present the general semantic horizon for this term prior to the YS. |

| 15 | The most notable break is the much discussed sūtra 3.37, te samādhāv upasargā vyutthāne siddhayaḥ, which states that if one is not careful these siddhis can become impediments to samādhi, that we can be overtaken by our own success. |

| 16 | kāya-rūpa-saṁyamāt tat-grāhyaśakti-stambhe cakṣuḥ prakāśāsaṁprayoge ‘ntardhānam. |

| 17 | bhuvana-jñānaṁ sūrye-saṁyamāt. |

| 18 | kāyākāśayoh sambandha-saṃyamāl laghutūlasamāpatteś cākāśagamanam. |

| 19 | See Sax 2002, 158ff., who speaks of oracular possession in terms of “complex agency.” The notion of assigning agency to non-human actors is controversial in anthropology, but my experience over the years in the Himalayas forces me to concur with Sax’s observations and conclusions. |

| 20 | This is described and analyzed at length in Smith (2006, chp. 12). |

| 21 | Most of this is also described in (Smith 2006). Some of what appears in the next few paragraphs is drawn from various parts of that publication. See also (Smith 2010). |

| 22 | See (Freeman 1993, 1998), on possession as learned behavior. |

| 23 | Although the actual beginning is at Gaumukh, 18 km further upriver, where the Bhagirathi emerges as a fully formed river from beneath the receding Gangotri glacier. However, it is only possible to travel there on foot. Thus, the temple, beyond which very few people go (the government imposed limit is 150 trekkers per day), is in the densely built up pilgrimage center of Gangotri. |

| 24 | The data and comments included here are based to some extent on my fieldwork at Balaji in 2001, 2002, and 2007, and participation in the Mukhba-Gangotri pilgrimages in 2007, 2013, 2015, and 2016. Much of this was conducted thanks to two senior research fellowships from the American Institute of Indian Studies in 2001 and 2006, and two from Fulbright, including a Fulbright-Hayes in 2007 and a Fulbright Nehru in 2015–2016. |

| 25 | Pakaslahti begins his important 1998 article by pointing to an article then twenty-five years old (Neki 1973), which needs to be updated, that provides an interesting statistic: “80% of the population first consult[s] religious folk healers when they seek outside help for mental health problems” (Pakaslahti 1998, p. 129). This statistic cannot have changed much in the last half century. |

| 26 | It is important to note that the healers who transit through Balaji operate through very different modalities even if nearly all of them advocate family therapy. They are not certified by any outside bureau or board; their procedures are highly idiosyncratic. Among other things this is a reason for more research to be conducted there. |

| 27 | See (Obeyesekere 1981; Erndl 1993; Hiltebeitel 1991), although some of this requires modification today. |

| 28 | The most promising theory is Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory (Latour 1996, 2005), which provides limited and contextual agency to non-human entities and objects; see (Sax 2009), for applying this to possession in the central Himalayas. |

| 29 | One can easily label this a shamanic scenario, and create a list of shamanic features, but the labeling is not important here. |

| 30 | |

| 31 | For example, see (Stanley 1977), for the festival at the Khaṇḍobā temple at Jejuri, fifty kilometers southeast of Pune the on the somavatī amāvāsyā or new moon that falls on a Monday; Hiltebeitel 1991 for the Draupadī festival in North Arcot district of Tamilnadu; (Sax 1991) for the pilgrimage to Nandadevi; and much more. See (Smith 2006, chp. 4), for further examples. |

| 32 | See (Smith 2006, p. 113) for the richness of the vocabulary of possession in North India. |

| 33 | In June 2018, quite by accident, I attended a village festival at Shri Dhan Singh Devta, Aleru, Tehri Garhwal, south of Chamba, on the road to Rishikesh. It began as a simple chai stop during my taxi ride. I soon heard drums beating up the hill behind the chai shop. I asked man at the chai shop about the commotion. He said simply, nāc, upar se mandir haiṃ, “they’re dancing up at the temple.” I quickly finished my chai and climbed the hill behind the chai shop to discover perhaps 150 people, in mid-morning, dancing, many of them, both men and women, exhibiting the characteristic behavior of possession. Dhan Singh was a resident who had died suddenly from cholera, and was transformed into a rathī devatā. The reason is because he was believed to have traveled to the heavenly world in a chariot (ratha). This piqued my interest for a number of reasons. Later, I discovered the videos of a young Garhwali filmmaker who calls himself Ashish Chamoli. in which all of this is explained. It is illuminating to watch the following; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8SzrmaIbNqM&t=105s (subtitled in English) Ashish Chamoli’s videography here is a good example of what can now be found scattered across the Youtube universe (and no doubt on social media) that is helpful in gaining access to cultural forms throughout the world. It is just as possible that I would not have seen this than that I did. |

| 34 | Presently D. R. Purohit, William Sax, and I are working to bring out an edition and translation of one version of the Garhwali Mahābhārata, the only one for which the recited text has been written down, hailing from the town of Agastmuni, along the Mandakini River north of Rudraprayag. |

| 35 | An outsider sensitive to other modes of thought might diagnose the initial possession as depression or anxiety. These concepts, at least as considered by western academics and the biomedical establishment, are not operable in rural India. The local interpretation, then, must be honored in order to abide by the dictum that the informant is always right. The notion of counter-possession is present not only in India but in Christian practice as well. Thiessen writes “Possession by the Spirit is a form of counter-possession in contrast to demon possession. If demons are dissociative phenomena, then positive possession by the Spirit is also a positive dissociative phenomenon” (Thiessen 2014, p. 183). |

| 36 | “As an indigenous category in ancient and classical India, possession is not a single, simple, reducible category that describes a single, simple, reducible experience or practice, but is distinguished by extreme multivocality, involving fundamental issues of emotion, aesthetics, language, and personal identity” (Smith 2006, p. 4). |

| 37 | This is covered in (Smith 2006, chp. 4), describing ethnographies (pp. 110–72), and chapter 9 on devotion explicitly articulated (pp. 345–62). Keep in mind that nearly all of South Asian religion is devotional, and any intense experience can lead to possession. This is generally acknowledged. |

| 38 | |

| 39 | |

| 40 | Such performances are almost always performed by lower caste bards in fairly small rooms with a relatively small audience. See (Alter 2018) for discussion of the music; (Sharma 2006, 2012) for a wealth of local information on jāgars; and (Bhatt et al. 2014) for an illuminating depiction of the use of jāgar in the Garhwal Himalayas. |

| 41 | See, for example (Mallinson 2011, 2012, 2016), and elsewhere; (White 2014; Vasudeva 2011) and others illustrate the bifurcation of the yoga tradition in which study of the Yogasūtras and its commentaries became limited to the paṇḍita or scholarly community while yoga practice was taken up largely by ascetics with their own very different textuality. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smith, F.M. The Fulcrum of Experience in Indian Yoga and Possession Trance. Religions 2019, 10, 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10050332

Smith FM. The Fulcrum of Experience in Indian Yoga and Possession Trance. Religions. 2019; 10(5):332. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10050332

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmith, Frederick M. 2019. "The Fulcrum of Experience in Indian Yoga and Possession Trance" Religions 10, no. 5: 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10050332

APA StyleSmith, F. M. (2019). The Fulcrum of Experience in Indian Yoga and Possession Trance. Religions, 10(5), 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10050332