1. Introduction

[…] In Pelarne parish, fourteen or fifteen years ago, there was a large wooden cross on the lands of Hult, along the road to Fastnefall, now downfallen; and it is said that formerly, the old and the sick have gone there, fallen to their knees and held their worship.

The statement above was written by a vicar in Småland in eastern Sweden in 1667 in a report to the College of Antiquities. Mentions of such sites are not uncommon from early modern Sweden. The vicar mentions that the cross was primarily used by “the old and the sick”, which implies that the cross was a form of semi-domestic alternative or complement to regular church attendance. In many parts of rural Sweden, the distance to one’s parish church could be considerable and roads were often in a poor state, which limited the ability to attend service regularly–and these difficulties doubtlessly increased for those in old age and failing health (

Kuha 2015, pp. 19, 22–23). To fulfil their religious needs, the laity could invest other sites than official church space with sacredness, sites that were convenient in their closeness to home while still maintaining something of the otherness of the holy.

Space offers an excellent opportunity to investigate religious cultures and in recent years, scholarly interest in spatial aspects of religious thought and practice have greatly increased (notable works include Alexandra Walsham, ‘The Reformation of the Landscape’, 2011 (

Walsham 2011); Andrew Spicer and Will Coster (eds.), ‘Sacred Space in Early Modern Europe’, 2005 (

Coster and Spicer 2005)). In general, though, the focus of scholars has been the “grand” spaces—towns, cathedrals and Western and Central Europe—while the rural village chapels of Eastern and Northern Europe have received less attention. The focus of this article is on these “small” spaces: devotional sites created and maintained by the laity in rural areas of Sweden. The study is carried out mainly through a close reading of seventeenth-century acts from the College of Antiquities, early modern topographical works and visitation records. In cases where the objects of these shrines have been preserved, the objects themselves will also be used as a source of analysis.

Most commonly, these shrines consisted of a simple wooden cross, but could also include saint’s sculptures and small chapels. They could be found in a variety of settings: on farmland properties, in the woods, on churchyards and crossroads. They were also often found in close proximity to holy wells. Holy wells and healing springs are the perhaps most well-known and subsequently the most researched example of landscape sites that bordered on domesticity. The overshadowing emphasis on miracles and healing makes the character of the visits to holy wells somewhat different from that of crosses, sculptures and other small shrines in the landscape, though this difference is by no means absolute—holy wells could be visited for prayer and crosses and images could be visited for healing as well as the reverse (

Ray 2014;

Christian 1989, pp. 93–97). The wells and springs themselves will, however, not be the focus of this particular piece, though they will be discussed on occasion in relation to the manmade shrines erected on its grounds.

In multi-religious areas, such as the Holy Roman Empire, the presence or absence of crucifixes, shrines and images could function as a way of claiming and confessionalising landscapes and public space (

Freist 2009, pp. 214–15;

Louthan 2005, pp. 286–96). This was likely not the case in early modern Sweden, which, with the exception of the easternmost part of Finland, did not border any areas where other faiths were commonplace. Thus, roadside shrines probably did not explicitly signal Catholicism in the same manner as these sites did in continental Europe, which could be a reason behind the viability of the custom of constructing and maintaining such shrines even in the post-reformation period.

The timeframe of the following study is deliberately kept elastic. This is due to the fact that many of the sources discussing the sites in question are vague in their descriptions of when a certain practice occurred or when an object was in place. Furthermore, even when specified, in certain cases there might be reason to suspect that these timeframes have been modified to suit the individual author’s purposes. This could be done as a rhetorical way of placing fairly recent practices in a distant “pagan” past, thus emphasising the author’s perception of pre-reformation religion as non-Christian. Timeframes could likely also be altered or kept vague for a different reason. To a vicar, admitting that illicit practices were continuously occurring in his parish might pose a risk in calling his office into question, and it could thus be safer to discuss questionable practices in the past tense. Geographically, this article investigates these practices in the Kingdom of Sweden as of its borders at the end of the seventeenth century. This included Sweden proper, as well as Finland and the provinces of Jämtland, Scania, Härjedalen Bohuslän, Halland and Blekinge, which had been acquired from Denmark and Norway earlier in the 1600s.

Religious traditions in the Scandinavian Middle Ages differed little from the beliefs and practices of other parts of Northern Europe (

Laugerud 2018, pp. 56–58), where we are more well-informed on the complex web of natural and manmade access-points to the sacred that characterised the religious landscape. Small prayer houses, crosses, sculptures and other shrines were scattered across Europe, fulfilling a variety of religious needs—most notably penance and healing. In remote areas where parishes were large, priests few and the churches far between, local holy sites may have been of greater importance than regular church attendance to these communities (

Walsham 2011, pp. 49–50). Because of the general scarcity of sources from medieval Sweden, mentions of these outdoor places of worship are few. When combined with records from other parts of Scandinavia though, a somewhat coherent context may be sketched. For instance, a twelfth-century Icelandic homily mentions such sites, in that it advices the faithful to hastily head to either “church or cross” in the morning, to kneel and sing the Pater Noster. Crosses could be erected by pious laypeople or by the Church, and in the former cases the crosses could be blessed by the local bishop. Their primal function was probably that of private worship for local residents and travellers, especially pilgrims passing on their way to the tomb of St. Olaf in Nidaros. Some were erected in the woods or along roads while others were placed in small chapel-like structures (

Gardell 1931, pp. 4–7). Though the medieval Church initiated, maintained and promoted many shrines in the landscape, some could still be met with suspicion and disapproval. When local cults initiated by the laity could not easily be brought under clerical control, such sites were often deemed superstitious (

Walsham 2011, pp. 66–79). Such non-official sites are largely unknown in a Scandinavian context, but considering the general shortage of preserved pre-reformation sources in the region, there is no reason to take this as proof of the absence of such shrines in the medieval period. There is, however, an important difference between wayside shrines in the medieval period and those in the post-reformation era. Devotions at these sites in the middle ages were usually firmly incorporated in the ecclesiastical sphere. They were visited on certain dates of the liturgical calendar, and sometimes even Mass was celebrated at portable altars in conjunction with these visits (

Timmermann 2012, p. 393). Post-reformation shrines, on the other hand, seem to have been kept and used exclusively by lay believers, and as such, they bordered more heavily on the domestic than the public spheres of worship.

Officially, the Kingdom of Sweden broke its ties to the Roman Catholic Church in 1527 and adopted Lutheran teachings. In reality though, changes in ecclesiastical law and liturgy were introduced step-by-step throughout the sixteenth century. During the 1544 ‘riksdag’ in Västerås, several traditional devotional practices, such as the veneration of saints, pilgrimages, masses for the dead and others, were officially abolished (

Alin and Hildebrand 1887, pp. 390–91). Among these changes, the banning of pilgrimage was probably the factor that had the greatest consequences for wayside shrines—though pilgrimage in various forms continued to be a part of popular religious repertoires throughout the early modern period (

Weikert 2004, p. 151;

Malmstedt 2014, p. 103). In the first Lutheran church ordinance, authored by Archbishop Laurentius Petri in 1561 (printed in 1571), Petri criticised the abundance of places of worship, stating that “unnecessary” churches, chapels and altars, had all led to a “great abuse” (

Nordström 1872, p. 99). While generally tolerating images in the churches, the ordinance also stressed that all “superfluous” images that were sought by “ignorant folk” were to be “taken off the road” [sv. taghas bortt aff wäghen] (

Nordström 1872, p. 101). This has sometimes been interpreted as specifically referring to the outdoor crosses, saint’s sculptures and other shrines that were placed along the roads (

Piltz 2016, pp. 76–77, 82), but it could also be a figure of speech and thus referring to “abused” images in general.

According to historical scholar Johannes Messenius (1579–1636), Archbishop Laurentius Petri had himself ordered the demolition of a famous miraculous crucifix that was placed at the Well of the Holy Cross [sv. Helga Kors Källa] in the parish of Svinnegarn (

Messenius 1703, 98v). However, apart from this story, we have very little evidence on how the process of removing such shrines played out in practice, or how far-reaching such initiatives were in reality. As will be discussed below, many shrines seem to have been preserved—sometimes even in locations where the local clergy surely must have been aware of their existence, such as churchyards and in connection to chapels. For instance, in 1707, the vicar of Särna in the province of Dalarna told the College of Antiquities that there was a moss-grown wooden cross of about two metres of height just outside of Idre parish church. The use of the cross was still in living memory, and parishioners had told the vicar that people previously made their worship there, “crawling on their hands and knees” (

Ståhle 1960, p. 166). That the cross was still in place in this central location, and that it had been in use up to at least some years following the reformation, was apparently not viewed as problematic in this context. However, as will be discussed in the following section, attitudes towards these shrines varied.

2. Votive and Devotional Crosses

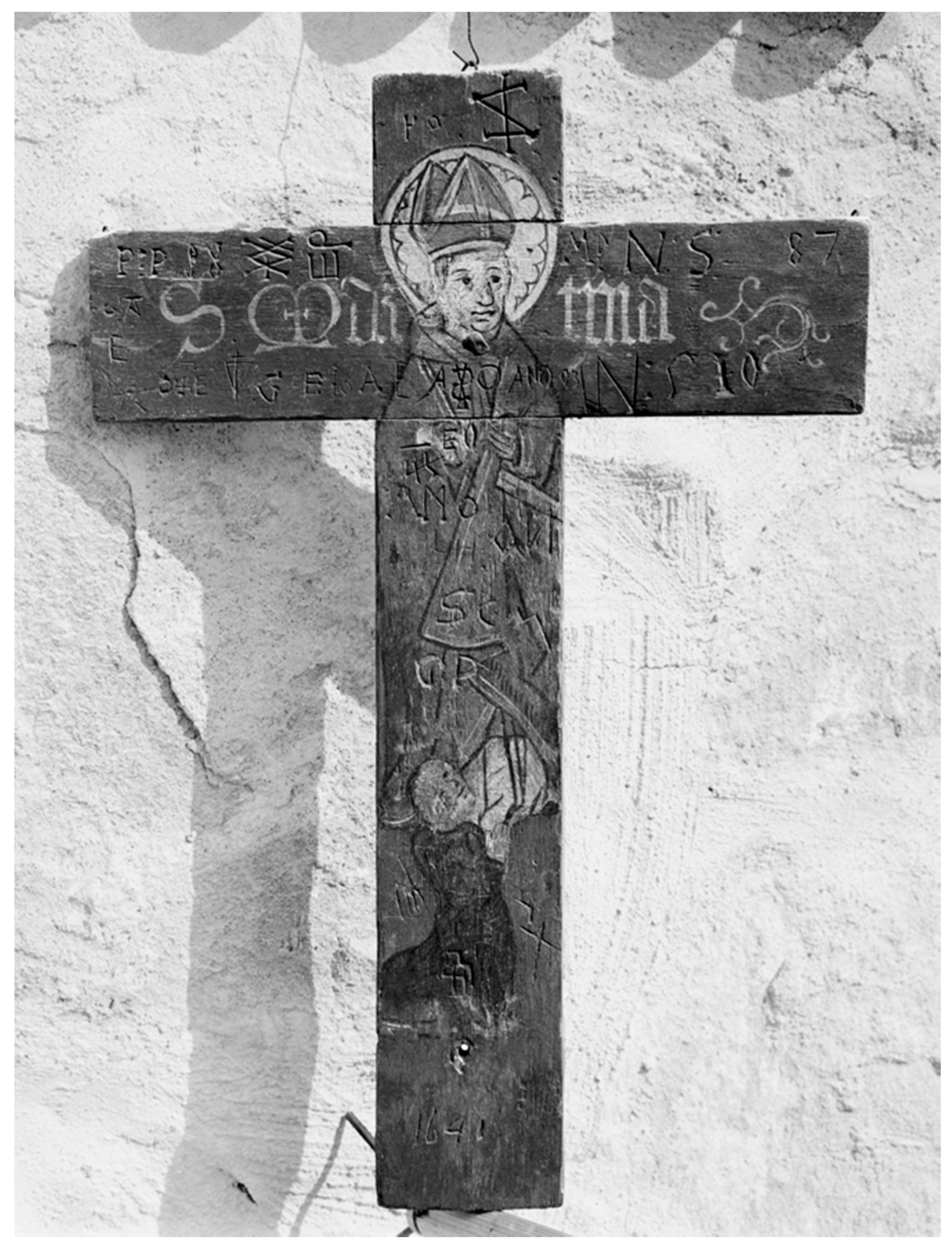

From the parish church of Liden in the province of Medelpad an unusual early 16th-century wooden cross is preserved (

Figure 1). It is painted with an image of St. Martin on one side and of St. Margaret on the other. The cross seems to have played a role in popular religion even in the post-reformation period, as indicated by the multitude of engravings covering its surface, consisting of initials, house marks and the year 1641. These engravings were possibly made in order to tie oneself or one’s household to the cross, or to that which the cross represented, and the cross was apparently used in this manner after the reformation as well as before. In a 1776 letter to Härnösand cathedral chapter, the local vicar describes a nearly identical cross preserved in Liden’s annex parish Holm. Instead of St. Martin and St. Margaret, this cross is said to have had paintings of the Virgin Mary and St. Joseph instead. Due to the unusual design—to my knowledge, the Liden cross is the only example of such a cross in Sweden—they seem to have been manufactured as a pair for the two churches. Another possibility is that the vicar was actually discussing the Liden cross, and that the images of Martin and Margaret had been reinterpreted as that of Mary and Joseph in a post-reformation context. In an inventory from 1831 the cross is described as “an old cross with painted images of humans on both sides, with unknown letters, that seem to be a remnant of paganism” (ATA: Holm 1831). Due to the mention of the house marks, his statement seems to support the idea that this was in reality the preserved Liden cross. House marks often took a runic form, and this could easily have been the unknown “pagan” letters referred to in the inventory. There is, of course, a possibility that the Holm cross, if a separate object, was also covered with similar marks, though this is somewhat unlikely due to the rarity of such inscriptions on images.

Regardless, the vicar continues his 1776 letter with saying that he had heard from his parishioners that “during the Papacy”, the cross had been placed in some sort of small structure at a placed called Korsmobacken in the woods between the Liden and Holm churches, and that it had functioned as “an offering stead” for those unable to walk the distance to either of the churches (HLA: Domkapitlet i Härnösand E III:76, Holm 1776-09-11). The cross was probably manufactured in the sixteenth century, placing this devotional custom on the “eve of the reformation”, and it is unlikely that the practice was ended abruptly as the new teachings were introduced. Rather, that parishioners had clear memories of how the cross had been used, even in the late eighteenth century, suggests that such customs continued into at least the seventeenth century, as indicated by the year carved into the cross along with the house marks. Similar statements, that project such practices to a vague “popish” or “pagan” past, are rather common in the sources. The fact that such objects existed in the pre-reformation period calls for little doubt; however, such statements could also have been made in order to disguise a more recent practice, and thus to evade possible criticism and sanctions from the cathedral chapter.

Though no longer part of officially sanctioned religious practices, wayside crosses continued to be a feature of the post-reformation landscape. Some of them, in particular memorial crosses, even survive to this day. These memorial crosses were often said to have been raised at sites where someone had met a violent end, in particular sites of murders and riding accidents. (

Säve 1873, pp. 4–20). Wayside crosses primarily serving a mnemonic function like these were likely never demolished in part because they were not tied to practices that the early modern Church perceived as threatening. Crosses used for devotional purposes are preserved to a much lesser degree because they were often constructed out of wood rather than stone, and likely also because they were associated with religious traditions that were frowned upon by the early modern Church. However, they certainly still existed in many parts of the country by the seventeenth century, and sometimes as late as the nineteenth century.

In 1666, in accordance with the Gothicist movement of the Swedish empire, the crown issued a decree for vicars and local officials to submit reports of historical monuments found in their parishes. What actually constituted a “monument” seem to have been subject to a wide range of interpretations and the acts submitted vary greatly in geographical distribution, length and quality (

Baudou 1995, pp. 164–68;

Bringéus 1995, pp. 92–93;

Zachrisson 2017, pp. 98–104). Still, these inventories, dating between 1667 and 1693, are invaluable sources for early modern folklore and material culture, and many wayside crosses are mentioned in these acts. For instance, in the parish of Tolg in Småland, the vicar of the area wrote of an old wooden cross by the name of “Three Lords” or “Lord Three” [sv. Herra Tre], that never seemed to rot (

Stahre 1992, p. 153).

An expression that seems to have been commonplace in early modern Sweden as well as in the other Scandinavian countries, when discussing someone lacking in piety was that he or she went to “neither cross nor church”. This suggests that the practice of visiting wayside crosses for devotional purposes had been far more common than what may be attested from preserved sources from the medieval period (

Gardell 1931, p. 7;

Bø 1964, p. 183). For example, one vicar, in writing to the College of Antiquities in 1683, tells us of the use of this expression in his parish:

Up and by the old Dalby church […], there has been a large wooden cross, six cubits high or long, outside of the gate of the church, and by the same cross there was a collection box. On Sundays and holidays where there was no service in the church, some of the peasants still went to the cross and made offerings in the box on behalf of their sick back at home. But if someone was negligent in their worship, other peasants would reproach him, saying that he goes to neither cross nor church, hence this expression has come in use in this area.

In Funäsdalen and Hede in the province of Härjedalen, remnants of a votive crosses [sv. Offerkors] could still be seen according to an antiquarian report from 1684, written by the vicar of the parish. At their bases, coins placed there as offerings had been found. However, the vicar was also quick to finish the sentence with a redeeming “—but not nowadays” (

Ståhle 1960, p. 245).

The practice of not only preserving, but also raising new crosses continued well into the post-reformation period, though it was regarded with suspicion by the clerical élite. When writing about the customs of the province of Hälsingland in the early 18th century, local pastor and schoolmaster Olof Broman wrote, with what appears to be a sigh of relief, that the custom of “raising crosses in woods, by the roads, on beaches and other places” was not as common as before (

Broman 1911–1949, p. 29). These crosses were used for a kind of semi-domestic devotion, as they were somewhere in the middle between the private and the public, between the familiar grounds of the home and the official space of the parish church. Records from the 17th and 18th centuries show that people approached these sites with bodily acts of reverence, such as kneeling, bowing and making the sign of the cross. Some sources also discuss how people interacted with these crosses in the pre-reformation period. An antiquarian report of 1668 mentions a cross placed in a pasture in Södra Åsarp parish, Västergötland, where “the simpleminded people read their rosaries during the Papacy” (

Ståhle 1969, p. 202).

In addition to the saying “neither church nor cross”, another common expression in these cases is the verb “krypa till korset”, which literally means “crawling towards the cross” The expression has since been incorporated into everyday modern Swedish, meaning to admit one’s fault or to “come crawling back”, but in these cases, it was used in a more literal sense. In the acts from the College of Antiquities, many sites figure where people claim such crosses had been used in penitential acts. In 1624, the vicar of Viby parish in Scania

1 tells of a hill called Korshøjenı [litterally “Cross-hight/hill”] where people had previously “crawled to the cross” (

Tuneld 1934, p. 166). In Tuna parish in Hälsingland, a report from 1686 states that a “votive board” [sv. Offertavla] had been placed by a crossroad, where the author uses the same expression for the penitential acts that had previously been carried out at the site (

Ståhle 1960, p. 201). A later comment further elaborates the ordeal that sinners underwent at the cross in Tuna, which perhaps has more to say of 18th-century anti-Catholic imagination than the actual traditions of the medieval era. According to Olof Broman, writing in the early 18th century, the site was still called Taveltäkten [literally “board-quarry”], because of the board shrine once placed there. The image consisted of a cross, lined with sharp rocks at its foot, and Broman continues to tell us that:

[…] those that were guilty and to be punished, or those wanting to show their repentance, had to crawl among these sharp stones on their bare knees, until their skin was shed and the blood was flowing. Because of this there is an expression: ’Go to Tuna and learn your manners!’.

The demonization of pre-reformation religious practices occasionally went so far as to, likely deliberately, misinterpret them as pre-Christian. On a hill outside the small village of Valparbo, Uppland, there had once been a pinewood cross, and when reporting this to the College of Antiquities in 1672, an official described the shrine as a place where “the pagans have made their offerings and committed their idolatrous worship”, all while maintaining that there were still men alive in the parish that remembered the now-ruined cross (

Ståhle 1960, p. 91).

In some areas, the practice of visiting wayside crosses for worship continued into the eighteenth century. One instance is mentioned briefly in a parish description from Bottnaryd in Småland, authored by Vicar Petrus Blidberg in 1742. The cross, which by the time of the description recently had been removed, had stood at a place called Korsängen [litterally“Cross-Meadow”], and the peasants had “always fallen to their knees and made the sign of the cross” before it when passing by on their way to church (SSLB Wilskman, vol. II). As such, this cross was clearly not just a complement or alternative to regular church attendance, but rather incorporated into weekly Sunday worship.

In 1727 Bishop Jesper Swedberg of Skara visited the parish of Broddetorp, Västergötland (GLA: Broddetorp C:2). During the visitation he was informed that at a place called Korstorp (literally “Cross-thorpe”), several crosses had been erected, and that “many superstitious people” went there to leave their offerings. In this case, the offerings consisted of items of clothing, which were hung from the crosses. The land on which the crosses stood was owned by the vicar of the parish, but was tenured to a local farmer. This implies the crosses must have been fairly close to the tenant’s dwelling, since such plots of land were rarely large. It was decided that the farmer was to be ordered to remove the crosses, in order to not let “such superstition” continue, and the vicar owning the land was to appear before the cathedral chapter. What is especially curious about this case is that it took place in a region that, though distinctively rural, cannot be called peripheral. Located among the fertile plains of south-western Sweden, the parishioners of Broddetorp would have had no trouble finding a parish church within walking distance. These shrines could apparently fill multiple functions, both incorporated in regular worship as in the previous case, and more unofficial ones that probably served religious needs that were not always fully catered for by the institutional Church.

The practice of bringing votives to crosses in the landscape is also documented from Finland, (

Arffman 2017, p. 259).

2 Most such crosses seem to have been in communal use, but there are some cases where they were raised and kept by a single individual or household. In relation to a 1670 visitation in Kuopio parish in Savolax, two neighbours had revealed that a farmer named Michel Owaskainen had made a shrine for himself in the woods. There he had raised a tall cross, which he was said to “worship”. When this came to the attention of Dean Cajanus of Kajaani, the dean decided that Michel himself was to “cut the cross down, and ruin its foundations”, and that he was not to be admitted to communion until he had done so. Apparently, Michel refused to cut his cross down. The case was mentioned briefly once again during the following year’s visitation, in that the local vicar was ordered to investigate the matter further. What came of this investigation, and whether Michel eventually submitted to the dean or not, we do not know, since the case is not discussed in later records (

Häkli 2015, p. 201).

In 1705, the brothers Per and Christopher Åmunds in Roma parish on the island of Gotland had raised a cross on their farm property, which was brought to light during a visitation by the superintendent. The brothers had previously had much ill fortune with their animals, and the cross was believed to prevent similar misfortune in the future. The superintendent declared their action as “superstition and idolatry”, but the custom was in reality quite common on the island (

Wikman 1947, p. 111). A detailed account on such a gårdskors (litterally “farmhouse-cross”) is preserved from the late 18th century. In the farmyard of a prosperous farmer in Källunge parish, a large crucifix of about five metres of height was in place in the 1780s. Each morning the entire household, from master to milkmaid, gathered by the cross. There they made their morning prayers while someone read a prayer of confession, “or at the very least an Our Father”. The children were kneeling by a rod or board at the foot of the cross, while the adults stood around with their hands folded, the menfolk baring their heads. Though the cross clearly belonged to this particular household, day labourers and servants from other farms sometimes went there with their children to pray too. When interviewed by nineteenth-century antiquarian P.A. Säve, an old man remembered how he, as a child, would ask the mistress of the house for bread, and that she used to chase him out of the kitchen telling him to go to the cross first, for a reminder of who was the real provider of all good gifts (

Wikman 1947, pp. 111–12).

As mentioned briefly in the introduction to this article, crosses were often raised at holy wells and other locations that were already invested with notions of sacrality. Even though the emphasis at these sites were the wells and springs themselves, crosses on the grounds further marked the sites’ sacred character. Such well-side crosses are known from several Swedish holy wells, such as St. Thorsten’s Well in Vättlösa and the Holy Cross Well [sv. Helge korss kella] in Mortorp (KoB Dahlb. III:49 Ex. I. Stahre 1992, p. 161)]. In 1719, when discussing two springs in Torpa in Västergötland dedicated to the Virgin Mary, topographer Nils Hufwedsson Dal mentions that next to the springs several crosses had been “raised by those that have benefited from the water or regained their health” (

Dal 1719, pp. 29–30). The practice of building a cross to show one’s gratitude is also evidenced from early modern Denmark, as in the case of the well-known St. Helen’s Well [da. Helle Lenes Kilde] in Tibirke (

Schmidt 1926, pp. 46–48). Votives in the form of clothing and human hair were sometimes left hanging from these wellside crosses. In the parishes of Lyngby and Kiaby in Scania, an antiquarian report from 1624 mentions several wooden crosses erected at S. Ellenis Kilde (“St. Helen’s well”) and at Hellig Trefolldigheds killde (“Holy Trinity Well”), where those seeking healing at the sites had hung pieces of cloth and tufts of hair (

Tuneld 1934, pp. 60, 159–60). Pieces of cloth were also hung upon the crosses raised among the holy birches of St. Ingemo in Dala, Västergötland (

Ståhle 1969, pp. 216–17), and strands of human hair were found on the crosses surrounding S. Nicolaj kilde (St. Nicholas’ Well) in Ödsmål, Bohuslän, as noticed by bishop Jens Nilssøn in the 1590’s (

Nilssøn 1885, pp. 164–65).

3. The Illicit Chapels in Jämtland and the “Vebomark God”

Though crosses were by far the most common form of these semi-domestic places of worship, they occasionally took other forms, such as lay-controlled small chapels and sculptures originally acquired for use in churches, transferred to a domestic or landscape setting.

On the 18th of February in 1621, an unusual case was brought before the regional court in Offerdal, in the province of Jämtland. Oluf Nielssen, vicar of Offerdal parish, had written to the bishop of Nidaros demanding a case of idolatry to be prosecuted. The “idolatry” in question centred on three “illicit chapels” in the area. When the parish church had been cleared of medieval sculptures following the Protestant reformation, the parishioners with the help of a former church warden, had managed to salvage some of the sculptures. The images had then been placed in three small chapels. Two of the chapels are mentioned as being located in the woodlands, and one on the properties of a farm named Landö. It is not clear whether these shrines were built by the laity themselves for this purpose, or if they were abandoned chapels that had previously been kept and administered by the pre-reformation Church. Vicar Nielssen stated in court that he, on many occasions, had ordered the peasantry to tear these chapels down, but that they had refused and insubordinately responded that if he wanted them gone, he would have to find someone else to do the deed.

During the trial, a man named Halvard Jonsen was brought forth, and he retold the story of how his late wife Magdalene, “out of ignorance” had made a promise during a difficult childbirth in 1598. If she were to be safely delivered, she vowed to give something to the image of St. Lawrence in the Landö chapel. Her prayer was answered and when she had recovered from the birth, she proved true to her word and walked a distance of 40 kilometres to the chapel, where she hung a neckerchief on the image. Another witness, Simen of Landön, then appeared and confessed that his mother-in-law Bente had chosen to leave the sculpture of St. Lawrence a part of her inheritance, likely textiles. Upon Bente’s death, her daughter had fulfilled her mother’s wish and “carried it there and hung it on the aforementioned image”.

The second of the three chapels was called Korset (The Cross). According to a witness who had apparently functioned as an unofficial church warden for this chapel, the means gathered from the offerings had been used to renovate or expand the chapel—which suggest that in addition to everyday objects, money was also donated. On the Korset chapel, the peasantry had pleaded with vicar Nielssen that they needed to keep it to “make their prayers in” (no. thill Att Bede dieris böner Udj), to which the vicar simply had responded with a laconic “no”. The trial was concluded with the burning of the “clothed” images, that had apparently been brought along to court, and the men of the parish were ordered do demolish the chapels themselves. Those still alive that were guilty of practicing superstition in any of the chapels were to stand kyrkoplikt—a form of public humiliation punishment in which the offender would publicly confess their sin in church before the entire parish (

Hasselberg 1933, pp. 18–20). These chapels were clearly outside the control of the institutional Church, and were kept and maintained solely by the laity. All named persons stated to have made offerings at the chapels, were conveniently already dead by the time of the trial, which probably reflects the parishioners’ unwillingness to betray their neighbours more than anything else. The fact that the images had been hung with items of clothing seems to have been an aggravating aspect in the case, with the court record mentioning in on several occasions.

Whether some of the wayside crosses discussed in the previous section were actually sculpted crucifixes is difficult to determine, since the words ‘kors’ and ‘krucifix’ were often used interchangeably in pre-modern sources (

Lange 1964, p. 175), but there are some examples mentioning proper sculptures being used by the laity for semi-domestic devotions. Three cases of images of saints that functioned as woodland shrines in a similar fashion as the wayside crosses are known from the sparsely populated woodlands of Västerbotten, northern Sweden. In his dissertation on the midnight sun, translated into English in 1698, theologian and cartesian philosopher Johan Bilberg recounts his visit to Bygdeå parish church in Västerbotten:

[…] there was the Picture of a certain Religious Person which was placed in a Wood half a Mile and more from thence; where formerly those who were Remote from Church, are said to have met together to Prayers, on Holy-Days; but after the most happy Times of Religion being purged from the Heresies of Papists, as that sort of Worship ceased in our Country, so the Picture was laid in a certain place of the Temple, in detestation of the Memory of that Matter.

A 1731 topographical dissertation on the area by Jonas Ask also mentions the “image of a holy man”, this time in Lövånger parish church. According to the parishioners, the image had been used in the same manner as the one in Bygdeå (

Ask 1928, p. 76). Even in the early twentieth century, the image was remembered in the parish, referred to as the “Vebomark God” (sv. Vebomarksguden) in folklore records from the area, as the image had been placed in a hollow tree in the Vebormark forest. Since 1924, a sculpture said to be the Vebomark God is kept in the collections of Västerbotten’s museum (

Figure 2). The image is severely damaged, with its hands and face cut off, which makes it difficult to established what saint it once represented, though the figure seems to be wearing the dress of a deacon (

Burman 2014, p. 51). Unfortunately, the sculpture is yet to be dated, which could have provided a more precise timeframe for when the Vebomark God was in use as an outdoor shrine.

A similar case from the same province is attested as late as in the 1800s, when artist and antiquarian Nils Månsson Mandelgren visited Skellefteå. He was told that up until 1823, a wooden image had been placed in a hollow tree in the Gärdsmark forest. Allegedly, this image had been “worshipped” by the local peasantry, and Mandelgren referred to this behaviour as “pure Catholicism” (Lund University Folklore Archives, Mandelgren: 5: Härnösand: Skellefteå).

Much further south, in Västergötland, another image bore a similarly suggestive name as the Vebomark God—the Grain God of Vånga (sv. Kornguden i Vånga). The use of this image, a thirteenth-century apostle (

Figure 3), first caught the attention of scholars when an elderly couple from Vånga visited a local museum in the 1870s. When confronted with the sculpture the man had exclaimed: “Look Wife—They have the Grain God here!”. When questioned he told the curator of the museum that the sculpture was known as the Grain God in the parish, and that before the image was transferred to the museum in the 1860s, in springtime, the villagers used to smuggle the sculpture out of the church at dawn to carry it across the fields in order to secure a good harvest (

Svanberg 1985, p. 259). Whether or not this tradition had developed from pre-reformation practices is unclear, since the earliest mention is found in a legal protocol from 1760, where a witness in an unrelated case was recorded absent from court due to being out “carrying the Grain God” for two days (

Bergstrand 1972, p. 18). Folklore about the Grain God is rather abundant from the late nineteenth- and early twentieth centuries, and while the records often bear the marks of local humour and tall tales, the sheer amount of the stories suggests that the sculpture was indeed being carried in procession at least up to the middle of the nineteenth century (

Svanberg 1985, pp. 259–60).

Other sculptures could be temporarily removed from their more permanent placements in churches and chapels to the actual homes of laypeople. This seems to have occurred in particular in association with childbirth. The axe of St. Olaf is one such example. Writing in 1760, travelling topographer Carl Frederic Broocman wrote of such an axe in the parish of Västra Husby, Östergötland. By the mid-eighteenth century, the sculpture of St. Olaf in the parish church was missing the axe that the Norwegian royal saint was usually depicted with. According to Broocman, this was the result of the continuous use of the axe by women in labour:

Of this image’s axe, it is said, that the peasantry has used it for birthing mothers, in the belief that its touch and placement would ease and quicken the birth; and that they have used it in this manner for so long, that it has subsequently gotten worn down and ruined.

Similarly, a sculpture of the Virgin, normally placed upon the “Women’s altar

3 (sv. Kvinnoaltare) in the church of Od, was reportedly lent to pregnant women across the surrounding area (

Hvarfner 1959, p. 36). A corresponding practice is also described from the pre-reformation era, where the Christ child could be borrowed from Madonna sculptures in such cases. The strength of this tradition could possibly be evident from the fact that the child was often sculpted separately from the Virgin for easy removal (

Stolt 1996, pp. 407–19). Such cases, while only rarely figuring in the sources, demonstrate the portable character of the sacred, and how the holiness of church space could be transferred to a domestic setting.

4. Concluding Remarks

From the medieval period, most of the sacred sites in the landscape that we have knowledge of today are those that were administered by the Church. In general, those of a more domestic, private character are unfortunately lost to us, but this should by no means be taken as evidence that such shrines were not present in the sacred landscape of the middle ages. Tales of such medieval sites were frequently told in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and were recorded by the antiquarians, clergymen and scientists of the era. To some degree, these stories surely reflect early modern prejudice towards a “superstitious” and “popish” pre-reformation culture, but they likely also contain elements of genuine memories from a not-too-distant past.

Achim Timmermann has suggested that in the late medieval period, such shrines functioned as thresholds, where mundane everyday spaces such as forest clearings, roads and pastures could temporarily transform into the true, spiritual landscape, providing glimpses of the path leading to God (

Timmermann 2017, p. 264). Perhaps this was also the experience of those that visited similar sites in the early modern era, though the available sources provide no such insights. However, these sites and objects were clearly important to the people that built, used and maintained them—so important that they on occasion defied the Church in order to keep them. In addition to prayer, people interacted with the sacred at these shrines by the use of bodily gestures such as kneeling, bowing and making the sign of the cross. They also frequently left votive gifts, often consisting of everyday domestic objects like clothing, at the sites. Votives were particularly important when petitioning for aid, and the issues mentioned in these cases are distinctively domestic in their character. When visiting such shrines, parishioners hoped for intervention in securing their health, a safe delivery, a good harvest and the welfare of cattle. In some cases, shrines were built within the bounds of farms and villages, while in others they were placed along roads and in the woods. Sometimes they could also be found in churchyards or just outside of the lychgate, functioning as an extension of church space that could be utilised when there was no service or the church itself was locked. There are several cases that show that both the maintenance of and the creation of new semi-domestic sacred sites continued well into the early modern period. If we are to look for explanations as to why these outdoor shrines remained in place for such a long period of time, despite the fact that the institutional Church disapproved of them, we might consider the physical environment in which these shrines were built. In the dense woodlands of the northern and eastern part of the realm, the distance to proper church buildings could call for complementary sites of worship closer to one’s home. With the reformation, a number of small chapels that had previously served such communities had been demolished or taken out of use, prompting parishioners to either maintain these buildings themselves, such as in the case from Jämtland, or to create new sites. But as the cases from Scania and Västergötland demonstrates, these sites could also be found in agricultural areas where the access to parish churches was not an issue. This suggests that these sites provided a complementary layer to religious life in more than purely spatial terms.

As to the question of what to make of this religious culture, and whether such traditions are to be interpreted as surviving features of pre-reformation piety or as distinctly Lutheran traditions, the issue is complex, and the answer, I would argue, lies somewhere in between. In areas where Catholic, Lutheran and Reformed communities lived side by side, such as in the principalities of the Holy Roman Empire, the physical environment functioned as a way to accentuate difference (

Freist 2009, pp. 214–15). This might have also been the case in the parts of Eastern Finland bordering Orthodox Russia—at the very least, the presence of a distinct group with a different faith worried Swedish authorities (

Toivo 2016, pp. 112–24). However, as for the rest of the kingdom, areas with different faiths were remote. In the seventeenth century, the discussions on religious tolerance that were underway in other parts of Europe were largely absent in Sweden—apart from foreign dignitaries and merchants, it had no significant religious minorities (

Ljungberg 2017, pp. 7, 22). It is possible that the general absence of the religious Other made the limits of Lutheranism more flexible in this area. Though the use of outdoor shrines sometimes worried local clergy and visiting bishops, no large-scale efforts to root out such traditions were ever attempted. In general, most clergymen seem to have chosen to turn a blind eye to practices bordering the limits of evangelical teachings, and as argued in the introduction of this article, the association of such shrines with Catholicism were likely not as strong in Sweden as in parts of Continental Europe. In traditions with a similar underpinning logic, such as offerings to sculptures and holy wells, local clergy sometimes even promoted and took part in these practices (

Zachrisson 2018, pp. 112–13).

Other studies have shown that the cult of the saints and other traditional religious practices persisted in various forms, both official and un-official, throughout the seventeenth, and sometimes into the eighteenth century in Scandinavia (

Laugerud 2018;

Malmstedt 2002;

Nyman 2002.) The use of outdoor shrines and wayside crosses was no different, though it was not a part of the official religious repertoire. The tradition of visiting outdoor shrines clearly has its origins in pre-reformation piety, but the intentions of participants in these visits likely underwent change throughout the rather vast timeframe of this study. There are, however, few credible indications that these visits took place in any other context than a Christian one, and the allusions to heathenry sometimes made by clergymen likely reflect an insistence on the illegitimacy of said practices rather than an actual parallel religious tradition with roots in pre-Christian times. That the religious culture of rural communities still heavily relied on physical focal points for interaction with the sacred seems apparent. The need for additional sacred space, as a semi-domestic complement to parish churches did not necessarily diminish in the wake of the reformation.