From Domestic Devotion to the Church Altar: Venerating Icons in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Adriatic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Introduction, Reception and Appropriation of Icon Painting in the Catholic West

3. The Veneration of Greek Icons in the Italian and Dalmatian Household

3.1. The Archival Evidence

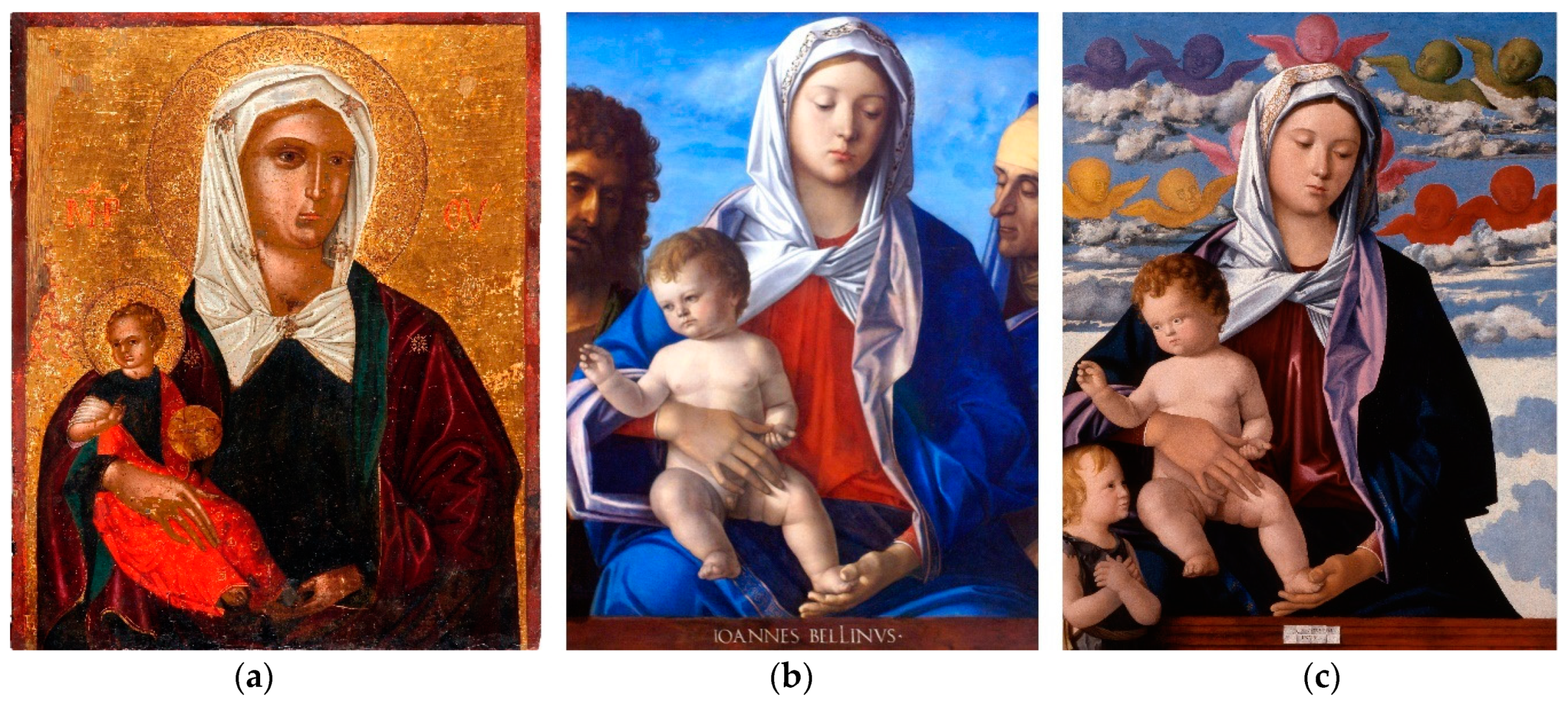

3.2. “Alla Greca” in the West, “Alla Latina” in the East: The Many Styles of Greek Icons

3.3. A World of Homely Madonnas and More: The Subjects of Greek Icons

3.4. The Display and Functions of Icons in the Domestic Space

3.5. From the House Tabernacle to the Church Altar: Icons of Domestic Devotion in the Public Space

“B. V. sopra tavola, fatta alla greca e presa dall’italiano di Sassoferrato, con cornice d’intaglio dorata lire 80; Decollazione di s. Giovan Batt. opera greca, sopra tavola, con cornice id. lire 120; S. Niccolò alla greca sopra tavola con cornice dorata lire 90; S. Stefano martire alla greca sopra tavola, con cornice antica dorata lire 50; S. Giorgio a cavallo alla greca id con cornice id lire 50; Sacra Famiglia alla greca id con cornice id. lire 80; Ecce-Homo alla greca id preso dall’italiano con cornice id. lire 80; B. V. col bambino, maniera greca sopra tavola con cornice id. lire 80; S. Spiridione maniera greca id, con cornice dorata d’intaglio lire 110.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

Archival Sources

Državni Arhiv u Dubrovniku (DAD).Published Primary Sources

- Apollonio, Ferdinando. 1880. Intorno all’Immagine e alla Chiesa di S. Maria della Consolazione al ponte della Fava. Venice: Tipografia dell’Immacolata. [Google Scholar]

- Armenini, Giovanni Battista. 1587. De’ veri precetti della pittura di M. Gio. Battista Armenini da Faenza libri tre ne’ quali con bell’ordine d’utili & buoni avertimenti, per chi desidera in essa farsi con prestezza eccellente, di dimostrano i modi principali del disegnare, & del dipignere, & di fare le pitture, che si conuengono alle conditioni de’ luoghi, & delle persone. Ravenna: Francesco Tebaldini. [Google Scholar]

- Armenini, Giovanni Battista. 1977. On the True Precepts of the Art of Painting. Edited and translated by Edward J. Olszewski. New York: B. Franklin. First published 1587. [Google Scholar]

- Borromeo, Federico. 1932. De pictura sacra. Edited by Carlo Castiglioni. Sora: P.C. Camastro. [Google Scholar]

- Cennini, Cennino. 1960. The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte). Edited and translated by Daniel V. Thompson. New Haven: Yale University Press. First published 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, Flaminio. 1749. Ecclesiae venetae antiquis monumentis nunc etiam primum editis illustratae ac in decades distributae. Venice: Typis Jo. Baptistae Pasquali. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, Flaminio. 1761. Notizie storiche delle apparizioni, e delle immagini piu celebri di Maria Vergine santissima nella citta, e dominio di Venezia. Tratte da documenti, tradizioni, ed antichi libri delle Chiese nelle quali esse immagini son venerate. Venice: Antonio Zatta. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, Giovanni. 1860. Regola del governo di cura familiare; compilata dal beato Giovanni Dominici, fiorentino. Firenze: A. Garinei. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiberti, Lorenzo. 1998. Lorenzo Ghiberti: I commentarii. Edited by Lorenzo Bartoli. Firenze: Giunti. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, da Pisa. 1867. Prediche inedite del b. Giordano da Rivalto dell’ ordine de’ predicatori: Recitate in Firenze dal 1302 al 1305. Edited by Enrico Narducci. Bologna: G. Romagnoli. [Google Scholar]

- Giustiniani, Paolo, and Pietro Quirini. 1773. B. Pauli Iustiniani Et Petri Quirini Eremitarum Camaldulensium Libellus ad Leonem X Pontificem Maximum. Edited by Anselmo Costadoni and Giovanni-Benedetto Mittarelli. In Annales Camaldulenses ordinis Sancti Benedicti, 9. Venice: Aere Monasterii Sancti Michaelis de Muriano, pp. 612–719. [Google Scholar]

- Leonardo, da Vinci. 1961. The Genius of Leonardo da Vinci; Leonardo da Vinci on Art and the Artist. Edited and translated by André Chastel. New York: Orion Press. [Google Scholar]

- Molanus, Joannes. 1570. De picturis et imaginibus sacris liber unus. Lovanii: H. Wellaeus. [Google Scholar]

- Molanus, Johannes. 1996. Traité des saintes images. Edited and translated by François Boespflug, Olivier Christin, and Benoît Tassel. Paris: Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Paleotti, Gabriele. 1594. De imaginibus sacris et profanis illusstriss. et reverendiss. D.D. Gabrielis Palaeoti cardinalis: Libri quinque. Quibus multiplices earum abusus, iuxta sacrosancti concilii Tridentini decreta, deteguntur. Ac variae cautiones ad omnium generum picturas ex Christiana disciplina restituendas, proponuntur … nunc primum Latine editi. Ingolstadium: Sartorius. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnelli, Pompeo. 1686. Lettere ecclesiastiche di Pompeo Sarnelli. Naples: Antonio Bulifon. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, Henry Joseph. 2011. Canons and decrees of the Council of Trent. St. Louis: Herder Book Co., Reprint Charlotte: TAN Books, trans. 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Vasari, Giorgio. 1550. Le Vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri. Florence: Lorenzo Torrentino. [Google Scholar]

Secondary Sources

- Abbate, Vincenzo. 2009. Il contesto familiare Mattei-De Torres e una riconsiderazione della copia palermitana dell’Emmaus di Londra. In Da Caravaggio ai Caravaggeschi. Edited by Maurizio Calvesi and Alessandro Zuccari. Rome: CAM Editrice. [Google Scholar]

- Ajmar Wollheim, Marta, and Flora Dennis. 2006. At Home in Renaissance Italy. London: V & A. [Google Scholar]

- Ajmar Wollheim, Marta, Flora Dennis, and Ann Matchette. 2007. Approaching the Italian Renaissance Interior: Sources, Methodologies, Debates. Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Caroline Corisande. 2007. The Material Culture of Domestic Religion in Early Modern Florence, c.1480–c.1650. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of York, York, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Antetomaso, Ebe. 2007. La collezione di oggetti liturgici del cardinale Bessarione. In Collezioni di antichità a Roma tra ’400 e ’500. Edited by Anna Cavallaro. Roma: De Luca, pp. 225–32. [Google Scholar]

- Aronberg Lavin, Marylin. 1975. Seventeenth-Century Barberini Documents and Inventories of Art. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, Michele. 2018. Devotional Panels as Sites of Intercultural Exchange. In Domestic Devotions in Early Modern Italy. Edited by Maya Corry, Marco Faini and Alessia Meneghin. Leiden: Brill, pp. 272–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bagemihl, Rolf. 1993. The Trevisan Collection. Burlington Magazine 135: 559–63. [Google Scholar]

- Barić, Ivo. 2007. Rapska baština. Rijeka: Adamić. [Google Scholar]

- Barocchi, Paola. 1961. Trattati d’arte del Cinquecento, fra Manierismo e Controriforma 2. Bari: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Basile Bonsante, Mariella. 2002. Arte e devozione: Episodi di committenza meridionale tra Cinque e Seicento. Galatina: Congedo. [Google Scholar]

- Battista, Giuseppina. 2002. L’educazione dei Figli nella Regola di Giovanni Dominici (1355/6–1419). Florence: Pagnini e Martinelli Editori. [Google Scholar]

- Bellavitis, Giorgio. 1975. Palazzo Giustinian Pesaro. Vicenza: N. Pozza. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans. 1985. Giovanni Bellini, Pietà: Ikone und Bilderzählung in der venezianischen Malerei. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans. 1994. Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bianca, Concetta. 1999. Da Bisanzio a Roma: Studi sul cardinale Bessarione. Rome: Roma nel Rinascimento. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Ilaria. 2008. La politica delle immagini nell’età della Controriforma. Il cardinale Gabriele Paleotti teorico e committente. Bologna: Compositori. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini, Geminiano, ed. 1995. Lettera al Papa: Paolo Giustiniani e Pietro Quirini a Leone X. Modena: Poligrafico Artioli. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Christopher F. 2004. Church, Religion, and Society in Early Modern Italy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, Henning, and Rainald Grosshans. 1996. Gemäldegalerie Berlin: Gesamtverzeichnis. Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz. [Google Scholar]

- Boni, Giacomo. 1887. Santa Maria dei Miracoli in Venezia. Archivio Veneto 33: 236–74. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Patricia Fortini. 2004. Private Lives in Renaissance Venice: Art, Architecture, and the Family. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brundin, Abigail, Deborah Howard, and Mary Laven. 2018. The Sacred Home in Renaissance Italy. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli, Vitaliano. 1913. Storia della città di Zara dai tempi più remoti sino al 1815, compilata sulle fonti da Vitaliano Brunelli. Venezia: Istituto Veneto d’Arte Grafiche. [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt, Jacob. 1898. Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte von Italien: Das Altarbild, das Porträt in der Malerei, die Sammler. Basel: Verlag von G.F. Lendorff. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelletti, Francesca. 2014. An Eye on the Main Chance: Cardinals, Cardinal-Nephews, and Aristocratic Collectors. In Display of Art in the Roman Palace, 1550–1750. Edited by Gail Feigenbaum and Francesco Freddolini. Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, pp. 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, Annemarie Weyl. 2004. Images: Expressions of faith and power. In Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557). Edited by Helen C. Evans. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 142–52. [Google Scholar]

- Carlton, Genevieve. 2015. Worldly Consumers: The Demand for Maps in Renaissance Italy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cattapan, Mario. 1972. Nuovi elenchi e documenti dei pittori in Creta dal 1300 al 1500. Thesaurismata 9: 202–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo, Sandra, and Silvia Evangelisti, eds. 2009. Domestic Institutional Interiors in Early Modern Europe. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzini, Patrizia. 2014. Lesser nobility and other people of means. In Display of Art in the Roman Palace, 1550–1750. Edited by Gail Feigenbaum and Francesco Freddolini. Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini, Isabella. 2000. Quadri e commercio a Venezia durante il Seicento: Uno studio sul mercato dell’arte. Venezia: Marsilio. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini, Isabella. 2005. Al servizio dei collezionisti. La professionalizzazione nel commercio di dipinti a Venezia in età moderna e il ruolo delle botteghe. In Il collezionismo a Venezia e nel Veneto ai tempi della Serenissima. Edited by Bernard Aikema, Rosella Lauber and Max Seidel. Venezia: Marsilio, pp. 151–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini, Isabella. 2008a. Collezionismo e cultura materiale. In Il collezionismo d’arte a Venezia. Dalle origini al Cinquecento. Edited by Michel Hochmann, Rosella Lauber and Stefania Mason. Venezia: Marsilio/Fondazione di Venezia, pp. 164–91. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini, Isabella. 2008b. Material Culture in Sixteenth Century Venice: A Sample from Probate Inventories, 1510–1615. Department of Economics Research Paper Series 14/08; Venice: University Ca’ Foscari of Venice. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, David. 1992. A Renaissance Cardinal and His Worldly Goods: The Will and Inventory of Francesco Gonzaga (1444–1483). London: The Warburg Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Chastel, André. 1988. “Medietas imaginis”: Le prestige durable de l’icône en Occident. Cahiers Archéologiques 36: 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidakis, Manolis. 1977. La peinture des "Madonneri" ou "vénéto-crétoise" et sa destination. In Venezia, Centro Di Mediazione Tra Oriente e Occidente, secoli XV–XVI: Aspetti e problemi, 2. Firenze: L. S. Olschki, pp. 673–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cherra, Diletta. 2006. Collezionismo e gusto per l’arte bizantina in Italia tra Trecento e Quattrocento. Bollettino della Badia Greca di Grottaferrata 3: 175–204. [Google Scholar]

- Concina, Ennio. 1998. Venezia e l’icona. In Venezia e Creta. Atti des Convegno internazionale di studi, Iraklion-Chanià, 30 settembre–5 ottobre 1997. Edited by Gherardo Ortalli. Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, pp. 523–42. [Google Scholar]

- Concina, Ennio. 2002. Giorgio Vasari, Francesco Sansovino e la Maniera Greca. In Hadriatica. Attorno a Venezia e al Medioevo. Tra arti, storia e storiografia, Scritti in onore di Wladimiro Dorigo. Edited by Ennio Concina, Giordana Trovabene and Michela Agazzi. Padova: Il Poligrafo, pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Constantoudaki, Maria. 1975. Μαρτυρίες ζωγραφικών έργων στο Χάνδακα σε έγγραφα του 16ου και 17ου αιώνα. Thesaurismata 12: 35–136. [Google Scholar]

- Constantoudaki, Maria. 2018. Aspects of artistic exchange on Crete: Questions concerning the presence of Venetian painters on the island in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In Cross-Cultural Interaction between Byzantium and the West, 1204–1669: Whose Mediterranean Is It Anyway? Edited by Angeliki Lymberopoulou. New York: Routledge, pp. 30–58. [Google Scholar]

- Corazza, Lucia. 2017. Corazza, Lucia. 2017. Il mercato di quadri nella Venezia del Cinquecento. Master’s thesis, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Venice, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Corbo, Anna Maria. 2004. Paolo II Barbo: Dalla mercatura al papato, 1464–1471. Roma: Edilazio. [Google Scholar]

- Corry, Maya, Deborah Howard, and Mary Laven, eds. 2017. Madonnas & Miracles: The Holy Home in Renaissance Italy. London and New York: Philip Wilson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Corry, Maya, Marco Faini, and Alessia Meneghin, eds. 2018. Domestic Devotions in Early Modern Italy. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Crouzet Pavan, Elisabeth. 1992. “Sopra le acque salse”. Espaces, pouvoir et societé à Venise à la fin du Moyen Âge. Roma: Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, Elizabeth. 2006. Inside the Renaissance house. London: V & A. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, Anthony. 1995. From Loot to Scholarship: Changing Modes in the Italian Response to Byzantine Artifacts, ca. 1200–1750. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 49: 237–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, Anthony. 1994. Byzantium, Italy & the North: Papers on Cultural Relations. London: Pindar Press, pp. 190–226. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, Anthony. 2000. La ‘questione bizantina’ nella pittura italiana: Una visione alternativa della maniera greca. In La Pittura in Italia: L’Altomedioevo. Edited by Carlo Bertelli. Milan: Electa, pp. 335–54. [Google Scholar]

- Čoralić, Lovorka. 2002. Prilog poznavanju prisutnosti i djelovanja hrvatskih trgovaca u Mlecima (15.–18. stoljeće). Povijesni Prilozi 22: 40–73. [Google Scholar]

- Demori Staničić, Zoraida. 1990. Neki problemi kretsko-venecijanskog slikarstva u Dalmaciji. Prilozi Povijesti Umjetnosti u Dalmaciji 29: 83–112. [Google Scholar]

- Demori Staničić, Zoraida. 2012. Javni kultovi ikona u Dalmaciji. Ph.D. disseration, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia. [Google Scholar]

- Demori Staničić, Zoraida. 2017. Javni kultovi ikona u Dalmaciji. Split–Zagreb: Književni Krug. [Google Scholar]

- Domijan, Miljenko. 2007. Rab: Grad Umjetnosti. Zagreb: Barbat. [Google Scholar]

- Drandaki, Anastasia. 2013. Icons in the devotional practices of Byzantium. In Heaven & Earth. 1: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections. Edited by Anastasia Drandaki, Demetra Papanikola Bakirtzi and Anastasia Tourta. Athens: Hellenic Ministry of Culture, pp. 109–14. [Google Scholar]

- Drandaki, Anastasia. 2014. A Maniera Greca. Studies in Iconography 35: 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- Duits, Rembrandt. 2011. Una icona pulcra. The Byzantine icons of Cardinal Pietro Barbo. In Mantova e il Rinascimento italiano: Studi in onore di David S. Chambers. Edited by Philippa Jackson, Guido Rebecchini and David Chambers. Mantova: Sometti, pp. 127–41. [Google Scholar]

- Duits, Rembrandt. 2013. Byzantine icons in the Medici collection. In Byzantine art and Renaissance Europe. Edited by Angeliki Lymberopoulou and Rembrandt Duits. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 157–88. [Google Scholar]

- Effenberger, Arne. 2004. Images of personal devotion: Miniature mosaic and steatite icons. In Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557). Edited by Helen C. Evans. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 209–12. [Google Scholar]

- . Farlati, Daniele. 1769. Illyricum Sacrum. IV. Venice: Apud Sebastianum Coleti. [Google Scholar]

- Fazinić, Alena. 1980. Pet stoljeća dominikanske prisutnosti na Korčuli (1480–1980). Croatica Christiana Periodica 4: 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fazinić, Alena. 2009. Korčulanska spomenička i kulturna baština. Korčula: Ogranak Matice Hrvatske. [Google Scholar]

- Fedalto, Giorgio. 1967. Ricerche storiche sulla posizione giuridica ed ecclesiastica dei Greci a Venezia nei secoli XV e XVI. Firenze: Olschki. [Google Scholar]

- Feigenbaum, Gail, and Francesco Freddolini. 2014. Display of Art in the Roman Palace, 1550–1750. Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Fillini, Matteo, and Luigi Tomaz. 1988. Le chiese minori di Cherso. Quaderni della Comunità Chersina 7. Vicenza: Tipografia Regionale Veneta Editrice. [Google Scholar]

- Fisković, Cvito. 1959. Slikar Angelo Bizamano u Dubrovniku. Prilozi Povijesti Umjetnosti u Dalmaciji 11: 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Folda, Jaroslav. 2015. Byzantine Art and Italian Panel Painting: The Virgin and Child Hodegetria and the Art of Chrysography. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg, David. 1971. Johannes Molanus on Provocative Paintings. De Historia Sanctarum Imaginum et Picturarum. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 34: 229–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio Zeniou, Stella, and Miroslav Lazović. 2006. Icônes de la collection du Musée d’Art et d’Histoire. Genève: Musées d’Art et d’Histoire. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, Italo. 1973. Le icone bizantine a mosaico. Milano: Stendhal. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco, Laurie, and Gino Corti. 2006. Lorenzo de’ Medici, Collector and Antiquarian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gamulin, Grgo. 1984. Dva djela Antonija Vivarinija u Hrvatskoj. Peristil 27–28: 147–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gavitt, Philip. 1990. Charity and Children in Renaissance Florence: The Ospedale degli Innocenti, 1410–1536. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geanakoplos, Deno J. 1955. The Council of Florence (1438–1439) and the Problem of Union between the Greek and Latin Churches. Church History 24: 324–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giani, Marina. 2018. Una santa orientale a Venezia. La «Passio» di Teodosia di Cesarea. Bisanzio e l’Occidente 1: 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Goffen, Rona. 1975. Icon and Vision: Giovanni Bellini’s Half-Length Madonnas. The Art Bulletin 57: 487–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goja, Bojan. 2014. Novi prilozi o baroknom slikarstvu u Zadru. Radovi Instituta za Povijest Umjetnosti 38: 133–50. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, Andrea. 2004. Creating and Recreating: The Practice of Replication in the Workshop of Giovanni Bellini. In Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion. Edited by Ronda Kasl. Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, pp. 91–127. [Google Scholar]

- Grubb, James S. 2000. House and Household: Evidence from Family Memoirs. In Edilizia privata nella Verona rinascimentale. Edited by Edoardo Demo, Paola Marini, Paola Lanaro and Gian Maria Varanini. Milano: Electa, pp. 118–33. [Google Scholar]

- Grubb, James S. 2004. Piero Amadi Acts Like His Betters: "Original Citizenship" in Venice. In A Renaissance of Conflicts: Visions and Revisions of Law and Society in Italy and Spain. Edited by John A. Marino and Thomas Kuehn. Toronto: Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, pp. 259–78. [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann, Fritz. 1963. Giovanni Bellini e i Belliniani. Venezia: Neri Pozza. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Chriscinda. 2011. What makes a picture?: Evidence from sixteenth-century Venetian property inventories. Journal of the History of Collections 23: 253–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochmann, Michel. 2005. Quelques réflexions sur les collections de peinture à Venise dans la première moitié du XVIe siècle. In Il collezionismo a Venezia e nel Veneto ai tempi della Serenissima. Edited by Bernard Aikema, Rosella Lauber and Max Seidel. Venezia: Marsilio, pp. 117–34. [Google Scholar]

- Janeković, Zdenka. 1996. ‘Pro anima mea et predecessorum meorum.’ The Death and the Family in 15th century Dubrovnik. Otium 3/1-2 / Medium Aevum Quotidianum 35: 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jestaz, Bertrand. 2001. Les collections de peinture à Venise au XVIe siècle. In Geografia del collezionismo: Italia e Francia tra il XVI e il XVIII secolo: Atti delle giornate di studio dedicate a Giuliano Briganti: (Roma 19–21 settembre 1996). Edited by Olivier Bonfait, Michel Hochmann, Luigi Spezzaferro and Bruno Toscano. Roma: École française de Rome, pp. 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Pamela M. 1997. Federico Borromeo e l’Ambrosiana: Arte e riforma cattolica nel XVII secolo a Milano. Milano: Vita e Pensiero. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Pamela M. 2004. Italian Devotional Paintings and Flemish Landscapes in the ’Quadrerie’ of Cardinals Giustiniani, Borromeo, and Del Monte. Storia dell’Arte 107: 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kakavas, Giorgos. 2003. Θέματα πατμιακής εικονογραφίας σε κρητικά τρίπτυχα του Βυζαντινού και Χριστιανικού Μουσείου. Deltion Christianikis Archaiologikis Etaireias 24: 293–306. [Google Scholar]

- Karbić, Marija, and Zoran Ladić. 2001. Oporuke stanovnika grada Trogira u arhivu HAZU. Radovi Zavoda za Povijesne Znanosti HAZU u Zadru 43: 161–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kasl, Ronda. 2004. Holy households: Art and devotion in Renaissance Venice. In Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion. Edited by Ronda Kasl. Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, pp. 58–89. [Google Scholar]

- Katušić, Maja, and Ivan Majnarić. 2011. Dopo la morte dell quondam signor Giouanni Casio dotor … Inventar ninskog plemića Ivana Kašića s kraja 17. stoljeća. Zbornik Odsjeka za povijesne znanosti Zavoda za povijesne i društvene znanosti Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 29: 219–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kolpacoff Deane, Jennifer. 2013. Medieval Domestic Devotion. History Compass 11: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, Karl. 1917. Nikolaus Ragusinus und seine Zeit. Jahrbuch Des Kunsthistorischen Institutes 11: 5–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ladić, Zoran. 2003. Legati kasnosrednjovjekovnih dalmatinskih oporučitelja kao izvor za proučavanje nekih vidova svakodnevnog života i materijalne kulture. Zbornik Odsjeka za Povijesne Znanosti Zavoda za Povijesne i Društvene Znanosti Hrvatske Akademije Znanosti i Umjetnosti 21: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ladić, Zoran. 2012. Last Will: Passport to Heaven. Urban Last Wills from Late Medieval Dalmatia with Special Attention to the Legacies Pro Remedio Animae and Ad Pias Causas. Zagreb: Srednja Europa. [Google Scholar]

- Lamers, Han. 2015. Greece Reinvented: Transformations of Byzantine Hellenism in Renaissance Italy. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, Cesare Augusto. 1900. Le collezioni veneziane d’arte e d’antichità dal secolo XIV. ai nostri giorni. Venice: F. Ongania. [Google Scholar]

- Lydecker, John Kent. 1987. The Domestic Setting of the Arts in Renaissance Florence. Unpublished Ph.D. disseration, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2007. Audiences and markets for Cretan icons. In Viewing Renaissance Art. Edited by Kim Woods, Carol M. Richardson and Angeliki Lymberopoulou. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 171–206. [Google Scholar]

- Maginnis, Hayden B. J. 1994. Duccio’s Rucellai Madonna and the Origins of Florentine Painting. Gazette des Beaux-Arts 123: 147–64. [Google Scholar]

- Maginnis, Hayden B. J. 2001. Images, devotion, and the Beata Umiliana de’ Cerchi. In Visions of Holiness: Art and Devotion in Renaissance Italy. Edited by Andrew Ladis, Shelley Zuraw and H. W. van Os. Athens: Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mattox, Philip. 2006. Domestic Sacral Space in the Florentine Renaissance Palace. Renaissance Studies 20: 658–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menna, Maria Raffaella. 1998. Bisanzio e l’ambiente umanistico a Firenze. Rivista dell’Istituto Nazionale d’Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte 3: 111–58. [Google Scholar]

- Menna, Maria Raffaella. 2015. Sulla disposizione delle icone bizantine nella collezione del cardinale Pietro Barbo. In Curiosa itinera: Scritti Daniela Gallavotti Cavallero. Edited by Enrico Parlato. Roma: Ginevra Bentivoglio Editori, pp. 101–11. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, Susan. 2009. The reception of garland pictures in seventeenth-century Flanders and Italy. In Domestic Institutional Interiors in Early Modern Europe. Edited by Sandra Cavallo and Silvia Evangelisti. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 201–20. [Google Scholar]

- Molmenti, Pompeo G. 1928. La storia di Venezia nella vita privata dalle origini alla caduta della repubblica, 2. Bergamo: Istituto Italiano d’Arti Grafiche, Firsted published 1880. [Google Scholar]

- Morini, Enrico. 1989. La Chiesa Greca ed i rapporti ‘in sacris’ con i Latini al tempo del concilio di Ferrara-Firenze. Annuarium Historiae Conciliorum 21: 267–96. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, Margaret Ann. 2006. The Arts of Domestic Devotion in Renaissance Italy: The Case of Venice. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, Margaret Ann. 2007. Creating sacred space: The religious visual culture of the Renaissance Venetian casa. Renaissance Studies 21: 151–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, Margaret Ann. 2013. The Venetian Portego: Family Piety and Public Prestige. In The Early Modern Italian Domestic Interior, 1400–1700. Edited by Erin J. Campbell, Stephanie R. Miller and Elizabeth Carroll Consavari. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Müntz, Eugène. 1879. Les arts à la cour des papes pendant le XVe et le XVe siècle: Recueil de documents inédits tirés des archives et des bibliothèques romaines, 2. Paris: Ernst Thorin. [Google Scholar]

- Müntz, Eugène, and Arthur L. Frothingham. 1883. Il Tesoro della basilica di S. Pietro in Vaticano dal XIII al XV secolo con una scelta d’inventarii inediti. Roma: Società Romana di Storia Patria. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, Alexander, and Christopher S. Wood. 2010. Anachronic Renaissance. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, Alexander. 2011. The Controversy of Renaissance Art. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray. 1988. Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noreen, Kirstin. 2005. The Icon of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome: An Image and Its Afterlife. Renaissance Studies 19: 660–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo Fossati, Isabella. 1984. L’interno della casa dell’artigiano e dell’artista nella Venezia del Cinquecento. Studi Veneziani 8: 109–53. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo Fossati, Isabella. 2004. La casa veneziana. In Da Bellini a Veronese: Temi di arte veneta. Edited by Gennaro Toscano and Francesco Valcanover. Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, pp. 443–92. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotakes, Nikolaos. 2009. El Greco: The Cretan years. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Pasi, Silvia. 1986. Icone tardo- e postbizantine in Romagna. Felix Ravenna 131–32: 99–162. [Google Scholar]

- Pasini, Pier Giorgio. 2000. Il Museo di Stato della Repubblica di San Marino. Milano: F. Motta. [Google Scholar]

- Pastega, Giuseppe. 2015. Gli Annali Guarnieri-Bocchi (1745–1848): Un secolo di cronaca e storia adriese. Adria: Apogeo Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Pedone, Silvia. 2005. L’icona di Cristo di Santa Maria in Campitelli: Un esempio di «musaico parvissimo». Rivista dell’Istituto Nazionale di Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte 60: 95–131. [Google Scholar]

- Piatnitsky, Yuri. 1993. Из кoллекций Н. П. Лихачева. Каталoг выставки в Гoсударственнoм Русскoм музее. Saint Petersburg: Издательствo Седа-с. [Google Scholar]

- Da Portogruaro, Davide. 1930. Il tempio e il convento del Redentore. Rivista mensile della città di Venezia 4–5: 141–224. [Google Scholar]

- Prodi, Paolo. 1973. The Structure and Organization of the Church in Renaissance Venice: Suggestions for Research. In Renaissance Venice. Edited by John Rigby Hale. London: Faber & Faber, pp. 403–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rallis, Georgios, and Michael Potlis. 1855. Σύνταγμα των Θείων και Ιερών Κανόνων των τε Aγίων και πανευφήμων Aποστόλων, και των Ιερών και Oικουμενικών και τοπικών Συνόδων, και των κατά μέρος Aγίων Πατέρων, 5. Athens: Εκ της Τυπογραφίας Γ. Χαρτοφύλακος. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, Corrado. 1901. La pittura a San Marino. Rassegna d’Arte 1: 129–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ringbom, Sixten. 1984. Icon to Narrative. The Rise of the Dramatic Close-Up Fifteenth-Century Devotional Painting. Åbo: Åbo Akademi. First published 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Alberto. 1972. Le icone bizantine e post-bizantine delle chiese veneziane. Thesaurismata 9: 250–91. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, Dennis. 1993. Aspects of patronage in fifteenth-and sixteenth-century Venice. Renaissance Quarterly 46: 712–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncalli, Angelo Giuseppe. 1945. Gli atti della Visita apostolica di S. Carlo Borromeo a Bergamo nel 1575. Vol. 2: La Diocesi. Parte 2. Fontes Ambrosiani 16. Firenze: Olschki. [Google Scholar]

- Sartori, Antonio. 1989. Archivio Sartori: Documenti di storia e arte francescana. Vol. 4, Guida della basilica del Santo, varie, artisti e musici al Santo e nel Veneto. Padova: Biblioteca Antoniana, Basilica del Santo. [Google Scholar]

- Savini Branca, Simona. 1964. Il collezionismo veneziano nel ‘600. Padova: CEDAM. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Victor M. 2005. Painted Piety: Panel Paintings for Personal Devotion in Tuscany, 1250–1400. Firenze: Centro Di. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitter, Monika Anne. 1997. The Display of Distinction: Art Collecting and Social Status in Early Sixteenth-Century Venice. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitter, Monika Anne. 2011. The Quadro da Portego in Sixteenth-Century Venetian Art. Renaissance Quarterly 64: 693–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, Anne Jacobson. 1999. Little women, great heroines: Simulated and genuine female holiness in early modern Italy. In Women and Faith: Catholic Religious Life in Italy from Late Antiquity to the Present. Edited by Lucetta Scaraffia, Gabriella Zarri and Keith Botsford. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 144–58. [Google Scholar]

- Schutte, Anne Jacobson. 2001. Aspiring Saints: Pretense of Holiness, Inquisition, and Gender in the Republic of Venice, 1618–1750. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sivrić, Marijan. 2002. Oporuke Kancelarije stonskog kneza od sredine 15. stoljeća do 1808. godine: Analitički inventar oporuka i abecedno kazalo oporučitelja. Dubrovnik: Državni Arhiv. [Google Scholar]

- Spallanzani, Marco. 1996. Inventari Medicei, 1417–1465 Giovanni di Bicci, Cosimo e Lorenzo di Giovanni, Piero di Cosimo. Florence: Associazione ‘Amici del Bargello’. [Google Scholar]

- Spallanzani, Marco, Giovanna Gaeta Bertelà, and Simone Di Stagio dalle Pozze. 1992. Libro d’inventario dei beni di Lorenzo il Magnifico. Florence: Associazione Amici del Bargello. [Google Scholar]

- Tadić, Jorjo. 1952. Građa o slikarskoj škole u Dubrovniku XIII-XVI v. Beograd: Naučna knjiga. [Google Scholar]

- Tassini, Giuseppe. 1891. Il Palazzo Gussoni. Nuovo Archivio Veneto Pubblicazione Periodica della R. Deputazione di Storia Patria 1: 433–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tassini, Giuseppe. 1915. Curiosità veneziane. Venice: Giusto Fuga. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasović, Marinko. 2013. Mijat Sabljar (1790.–1865.) i Makarsko primorje. Makarska: Gradski Muzej Makarska. [Google Scholar]

- Tosini, Patrizia, ed. 2009. Arte e committenza nel Lazio nell’età di Cesare Baronio: Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Frosinone (Sora, 16–18 maggio 2007). Roma: Gangemi. [Google Scholar]

- Trexler, Richard C. 1980. Public Life in Renaissance Florence. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turchi, Giovanni. 1829. Memorie istoriche di Longiano. Cesena: C. Bisazia. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilaki, Maria. 2008. Icons. In The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies. Edited by Elizabeth Jeffreys, John F. Haldon and Robin Cormack. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 758–69. [Google Scholar]

- Vlassi, Despina Er. 2008. Le richezze delle donne. Pratica testamentaria in seno alle famiglie greche di Venezia (XVI–XVIII sec.). In Oltre la morte. Testamenti di Greci e Veneziani redatti a Venezia o in territorio greco-veneziano nei sec. XIV–XVIII. Edited by Chryssa Maltezou and Gogo Varzelioti. Venice: Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini di Venezia, pp. 83–117. [Google Scholar]

- Voulgaropoulou, Margarita. 2007. Επιδράσεις της βενετσιάνικης ζωγραφικής στην ελληνική τέχνη από τα μέσα του 15ου έως τα μέσα του 16ου αιώνα [Influences of Venetian Painting on Greek Art from Mid-Fifteenth to Mid-Sixteenth Century]. Master’s thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Voulgaropoulou, Margarita. 2014. H μεταβυζαντινή ζωγραφική εικόνων στην Aδριατική από το 15ο έως το 17ο αιώνα [Post-Byzantine Icon-Painting in the Adriatic from the Fifteenth to the Seventeenth Century]. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Voulgaropoulou, Margarita. Forthcoming. Transcending Borders, Transforming Identities: Travelling Icons and Icon Painters in the Adriatic Region (14th–19th centuries). In re•bus, 10th Anniversary Issue, “Mobility, Movement and Medium: Crossing Borders in Art”. Essex: Re·bus.

- Walberg, Helen Deborah. 2004. “Una compiuta galleria di pitture veneziane”: The Church of S. Maria Maggiore in Venice. Studi Veneziani 48: 259–305. [Google Scholar]

- Walsham, Alexandra. 2014. Holy Families: The Spiritualization of the Early Modern Household Revisited. Studies in Church History 50: 122–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Diana. 2005. Domestic Space and Devotion in the Middle Ages. In Defining the Holy: Sacred Space in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Edited by Sarah Hamilton and Andrew Spicer. London: Routledge, pp. 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Živković, Valentina. 2016. The Deathbed Experience–Icons as Mental Images Preparations for a Good Death in Late Medieval Kotor (Montenegro). Ikon 9: 221–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccari, Alessandro. 1984. Arte e committenza nella Roma di Caravaggio. Torino: ERI, Edizioni Rai. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The episode is commemorated in a dedicatory inscription at the ex-church of Our Lady of Tears (Santa Maria delle Lacrime) in Longiano: D.O.M. // BEATISSIMAEQUE VIRGINI // LACRIMARUM // QUAE// ANNO CIƆIƆVI POSTRID. K. MAR // SUDORE MANAVIT // SEBASTIANUS BARBERIUS // DOMUM IN TEMPLUM D.D.D.S. // QUODQ. VETUSTATE COLLABENS // CONSULES LONZANI // A FUNDAMENTIS IN HANC FORMAM AEDIF. CIƆIƆCCLXXII. The inscription is cited and transliterated in (Turchi 1829, pp. 4–5). See also (Pasi 1986, pp. 156–58). |

| 2 | (Palumbo Fossati 1984; Lydecker 1987; Grubb 2000; Brown 2004; Palumbo Fossati 2004; Ajmar Wollheim and Dennis 2006; Currie 2006; Ajmar Wollheim et al. 2007; Anderson 2007; Cavallo and Evangelisti 2009; Henry 2011; Morse 2013; Feigenbaum and Freddolini 2014; Walsham 2014; Corry et al. 2017; Brundin et al. 2018; Corry et al. 2018). |

| 3 | For the role of icons in Byzantium see (Belting 1994; Carr 2004, pp. 142–52; Vassilaki 2008, pp. 758–69; Drandaki 2013, pp. 109–14). |

| 4 | For the diffusion of icon worship in the West see (Ringbom [1965] 1984, pp. 12–22; Belting 1994; Carr 2004, pp. 142–52; Drandaki 2013, pp. 109–14; Bacci 2018, pp. 272–92). |

| 5 | “Τινὲς τῶν Λατίνων εὑρίσκονται μὴ καθόλου διαφερόμενοι πρὸς τὰ καθ’ ἡμᾶς ἔθη […] τῶν ἁγίων γὰρ εἰκόνων εἰσὶ καὶ οὗτοι προσκυνηταὶ, καὶ ἐν τοῖς κατ’ αὐτοὺς ναοῖς ἀναστηλοῦσιν αὐτάς”. (Rallis and Potlis 1855, p. 434; Morini 1989, p. 267). |

| 6 | In his life of Cimabue Giorgio Vasari relates the emergence of Italian panel painting to the presence of “Greek painters”, who had been invited to Florence “for no other purpose than that of introducing there the art of painting, which in Tuscany long had been lost” [“Avenne che in que’ giorni erano venuti di Grecia certi pittori in Fiorenza, chiamati da chi governava quella città non per altro che per introdurvi l’arte della pittura, la quale in Toscana era stata smarrita molto tempo”]. (Vasari 1550, p. 126; cited and translated in Maginnis 1994, p. 147; Concina 2002, pp. 89–96). See also Voulgaropoulou (Forthcoming). |

| 7 | For the development of Italian panel painting see (Folda 2015, pp. xxii–xxiii, with references). |

| 8 | “Il quale Giotto rimutò l’arte del dipignere di Greco in Latino e ridusse al moderno”. |

| 9 | “Arrechò l’arte nuova, lasciò la rozeza de’ Greci”. |

| 10 | “[…] come vedemo in ne’ pittori dopo i Romani, i quali sempre imitarono l’uno dall’altro, e di età in età sempre mandarono detta arte in declinazione”. |

| 11 | “la maniera goffa greca”, “rozza maniera Bizantina”, “altre mostruosità di que’ Greci”, “quella maniera greca goffa e sproporzionata”. |

| 12 | For the Council of Ferrara–Florence see (Geanakoplos 1955, pp. 324–46; Nicol 1988, pp. 376–79; Morini 1989, pp. 267–96). |

| 13 | The common Ottoman threat created a sense of solidarity between Greek and Latin Christians, especially considering that a large part of the Byzantine refugees had accepted the Union of Florence and converted to Catholicism. Although short-lived, the Union of Florence had cultivated a favorable environment for Orthodox Christianity in the Catholic West, especially in Venice, where there was more tolerance towards doctrinal differences. Quite revealing is a letter of the Camaldolese monks, Paolo Giustiniani and Vincenzo Querini to pope Leo X in 1513, claiming about the Greeks that “they are true Christians; we half-pagan” (“hi Christiani vere sunt, nos semipagani”). (Giustiniani and Quirini 1773, p. 662; Bianchini 1995, p. 75; Prodi 1973, pp. 422–23. See also Nagel 2011, p. 21; Lamers 2015, p. 5). |

| 14 | “sicchè queste dipinture, e specialmente l’antiche, che vennono di Grecia anticamente, sono di troppo grande autoritade; perocchè là entro conversaro molti santi che ritrassero le dette cose e diederne copia al mondo, delle quali si trae autorità grande, siccome si trae di libri”. |

| 15 | This is explicitly decreed in the twenty-fifth and last session of the Council, which took place on 3–4 December, 1563: “[…] picturis vel aliis similitudinibus expressas erudiri et confirmari populum in articulis fidei commemorandis et assidue recolendis; tum vero ex omnibus sacris imaginibus magnum fructum percipi non solum quia admonetur populus beneficiorum et munerum quae a Christo sibi collata sunt sed etiam quia Dei per sanctos miracula et salutaria exempla oculis fidelium subiiciuntur ut pro iis Deo gratias agant ad sanctorum que imitationem vitam mores que suos componant excitentur que ad adorandum ac diligendum Deum et ad pietatem colendam […] Quodsi aliquando historias et narrationes Sacrae Scripturae cum id indoctae plebi expediet exprimi et figurari contigerit: doceatur populus non propterea divinitatem figurari quasi corporeis oculis conspici vel coloribus aut figuris exprimi possit”. For the English translation of the excerpt see (Schroeder 2011): “by means of the stories of the mysteries of our redemption portrayed in paintings and other representations the people are instructed and confirmed in the articles of faith, which ought to be borne in mind and constantly reflected upon; also that great profit is derived from all holy images, not only because the people are thereby reminded of the benefits and gifts bestowed on them by Christ, but also because through the saints the miracles of God and salutary examples are set before the eyes of the faithful, so that they may give God thanks for those things, may fashion their own life and conduct in imitation of the saints and be moved to adore and love God and cultivate piety […]this is beneficial to the illiterate, that the stories and narratives of the Holy Scriptures are portrayed and exhibited, the people should be instructed that not for that reason is the divinity represented in picture as if it can be seen with bodily eyes or expressed in colors or figures”. For the consideration of painting as Poor Man’s Bible (Biblia pauperum) and live scripture see (Paleotti 1594, p. 288; Barocchi 1961, p. 408; Molanus 1570, pp. 15, 32; Molanus 1996, pp. 125–27). |

| 16 | For the so-called “early Christian revival” of the end of the sixteenth century see (Zuccari 1984, pp. 49–52, 64, 80, 94; Bianchi 2008, vol. 11, pp. 84–85; Tosini 2009). |

| 17 | “usum a primaevis christianae religionis temporibus”. [following the sacred writings and the ancient tradition of the Fathers]. Sessio XXV 3–4 dec. 1563. Cf. the treatises of Molanus and Gabriele Paleotti. |

| 18 | “Dipingere le sacre imagini oneste e devote, con que’ segni che gli sono stati dati dagli antichi per privileggio de la santità, il che è paruto a’ moderni vile, goffo, plebeo, antico, umile, senza ingegno et arte”. |

| 19 | “His adde, quod Gulielmus Durandus Mimatensis Episcopus scribit de quibusdam Graecanicis Ecclesiis in Rationali divinorum officiorum, Graeci, ait, utuntur imaginibus, pingentes illas ut dicitur, solum ab umbilico supra & non inferius, ut omnis stultae cogitationis occasio tollatur”. |

| 20 | “Per prima io le desidero a mezzo busto. Così fù l’antico uso de’ Christiani ritenuto da greci per degni rispetti […] tanto che spirano divozione e maestà sopraumana; ancorche l’opera non appaja secondo le regole dell’arte […] Pittori de nostro secolo, che hanno profanato in maniera le sacre pitture, che non solamente non si ponno adorare, ma nè men rimirare con occhio puro, havendo introdotta la nudità infin sopra gli Altari”. |

| 21 | In 1597, Borromeo assigned the German artist Hans Rottenhammer and the Spanish Dominican Alphonsus Ciacconius with the task of locating the “original portraits” of Doctors of the Eastern Church in Venice and Rome, respectively, cities with strong Byzantine associations. Rottenhammer’s inquiry proved fruitless, so he proposed to have the portraits commissioned from a Greek artist residing in Venice, whom he, however, dismissed as a less skillful painter (“non è troppo maestro”). On the other hand, Ciacconius informed Borromeo that he had discovered certain portraits of Orthodox saints, which had been “carried off from Constantinople”. See (Jones 1997, pp. 190–92, 205n94). Although most portraits have been attributed to Giuseppe Franchi, the close resemblence of certain ones among them with popular iconographic models or types associated with Greek icon-painting workshops (for example the one of Ioannes Permeniates in Venice), suggests the possibility that the images could have been modelled after original Greek designs or executed with the assistance of a Greek-speaking icon painter. |

| 22 | “per molti palagi e case, e fino nelle camere secrete […] e tutte ho veduto essere con mirabil arte fornite, eccetto di pitture delle sacre imagini, le quali erano la maggior parte quadretti di certe figure fatte alla greca, goffissime, dispiacevoli e tutte affumicate”. |

| 23 | The display and uses of icons in Italian and Dalmatian households bear striking similarities with relevant practices documented in Venetian Candia. See (Constantoudaki 1975, pp. 36–74). |

| 24 | For the presence of Italian artists in Venetian Candia see (Constantoudaki 2018, pp. 30–58). |

| 25 | For icons in the collections of the broad Adriatic region see (Voulgaropoulou 2014). |

| 26 | In his Regola Del Governo Di Cura Familiare, Giovanni Dominici went as far as to encourage children to worship icons in private, sometimes even by engaging in ritualistic practices that involved dressing up like priests, and playing Mass around toy altars in imitation of what occurred publicly at church. (Dominici 1860, pp. 132–33). For Giovanni Dominici’s pedagogical views see also (Battista 2002, pp. 126–38; Webb 2005, pp. 34–35; Morse 2006, pp. 170, 307, 313–14n135; Kolpacoff Deane 2013, p. 69; Drandaki 2014, pp. 45–46). |

| 27 | It is far from surprising that icons were also found in private chambers in the households of Greek migrants in Venice. (Vlassi 2008, pp. 96–97). |

| 28 | For the Venetian quadro da portego see (Schmitter 2011, pp. 693–751). |

| 29 | |

| 30 | The same story with slightly differering details is reproduced by Helen Deborah Walberg. (Walberg 2004, pp. 261–69). |

| 31 | The idea to place the icon in a church was first revealed by divine inspiration to the wife of Francesco, head of the Amadi household, as evidened in the copy of an annotation in the Annali Guarnieri-Bocchi, which reads: L’anno 1480 Per rivelazione / dalla moglie di un Francesco / Amadi fu edificato l’oratorio de[lla] / Madona della fava deta anche / di consolazione il quale prima / era un cappitello depinto con una / inmagine di Maria operando / miracoli si edifico il luogo. Si crearono 6 procuratori Tre / nobili tre cittadini includendo / in questo numero gli Amadi. (Pastega 2015, p. 276). See also (Apollonio 1880, pp. 11–12). |

| 32 | Giuseppe Tassini offers an alternative account, according to which the icon hung on the walls of Ca’ Dolce and not Ca’ Amadi, and that in the year 1496 the parish priest of San Lio, Natale Colonna, Giacomo Gussoni, and other patricians bought out the two houses of the Dolce family to build a small church and move the icon to a more dignified place. (Tassini 1891, pp. 436–37; Tassini 1915, p. 234). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Voulgaropoulou, M. From Domestic Devotion to the Church Altar: Venerating Icons in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Adriatic. Religions 2019, 10, 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10060390

Voulgaropoulou M. From Domestic Devotion to the Church Altar: Venerating Icons in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Adriatic. Religions. 2019; 10(6):390. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10060390

Chicago/Turabian StyleVoulgaropoulou, Margarita. 2019. "From Domestic Devotion to the Church Altar: Venerating Icons in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Adriatic" Religions 10, no. 6: 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10060390

APA StyleVoulgaropoulou, M. (2019). From Domestic Devotion to the Church Altar: Venerating Icons in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Adriatic. Religions, 10(6), 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10060390