1. Introduction

Narration is one of the seven forms of dialogue between people (

Merdjanova and Brodeur 2011). Stories allow individuals to explain the reality in which they live, with all its complexities (

Payne 2002). From an anthropological point of view, journalism and religions share a similar function (

Didion 1979;

Sharlet 2014).

The social function of journalism is to improve democracy (

Schudson 2011;

Tocqueville 1835), a democracy in which societies coexist peacefully and have their fundamental rights guaranteed. In fact, information and knowledge have become key factors for social and economic development (

Bell 1973). The past decade has been a turning point for the three social environments represented by the publications analysed in this research. Two key factors shaped an era, a society, and the media that emerges from it: the economic crisis of 2008 and the consolidation of the digital and global era (

Herrscher 2014). Both phenomena have forced journalism to reinvent itself (

Greenberg 2018;

Rosenberg 2018;

Schudson 2011), to look for new forms of power and, at the same time, fulfil its social function while also generating sufficient benefits for journalists to earn a living from their profession (

Albalad 2018;

Benton 2018;

Sabaté et al. 2018b;

Berning 2011).

Multiple business models have emerged to seek this balance. Meanwhile, the world media map has multiplied (

Albalad and Rodríguez 2012), with the emergence of new publications that have contributed to the existence of a competition for exclusivity, for being the first to cover a story, achieve a greater audience, and continue to feed the advertising model that, in many cases, has stopped working (

Neveu 2016). This so-called fast journalism (

Le Masurier 2015;

Greenberg 2015) manifests the rhythm of a liquid modernity (

Ray 2007) in which knowledge needs somewhere to fit (

Durham Peters 2018). The concept of liquid modernity refers here to the Zygmunt

Bauman (

2013) term that emphasises that changes in modern society are rapid and continuous. The mentioned authors argued that fast journalism reflects this rapid and continuous change in which society lives. At the same time,

Durham Peters (

2018) wondered which is the place and the format to keep and consolidate knowledge in this context. For him, slow journalism appears as a reaction to this liquid modernity, as a claim for a slowness, a space where knowledge could be better kept and consolidated. This situation is taking place at the same time as population movements are increasing around the world (

United Nations Refugee Agency 2018). The global society has created new spaces of coexistence (

Candidatu et al. 2019;

Volf 2015) in which the mutual knowledge between cultures, traditions, and religions is the path towards peace (

Abu-Nimer 1996;

Johnston and Sampson 1994;

Lederach 1999).

Huntington (

1996) predicted that future conflicts would be more driven by cultural factors than by economic ones. Therefore, a model for coexistence is one of the most important challenges (

Fahy and Bock 2019;

Ratzmann 2019;

Ahmed 2018;

Ares 2017) at a time in which, despite their digital presence, many cultural and denominational communities do not communicate with each other (

Díez et al. 2018). In this sense, journalism acquires a relevant role (

Pousá 2016).

In this context, narrative journalism emerges as a space where it could be possible to address this twofold challenge. In the first case, the media space has given rise to new publications that are based on this technique, which break the rules of the digital world (

Sabaté et al. 2018a) and is determined by a tradition loyal to the type of journalism practiced by

Wolfe (

1973). In the digital age, narrative journalism is considered a space for knowledge (

Durham Peters 2018), and contemporary society and its main challenges are reflected in it. Religions and interfaith dialogue are among the most complex topics covered by this type of publication (

Griswold 2018;

Sharlet 2018). Religious traditions are key actors in today’s world, as a cause for peace but also of conflicts based on ignorance, fear of the Other, and the difficulty of empathising with that which is considered different (

Abu-Nimer and Alabbadi 2017). The rise of fake news (

Quandt and Schatto-Eckrodt 2019) and hate speech (

Parekh 2019;

Gagliardone et al. 2015) on social networks is proof of the risks of the model followed thus far and of the massive promotion of prejudices (

Restrepo 2019;

Durham Peters 2018).

Narrative journalism may possibly reveal itself as a space for encounter, knowledge, and dialogue, which presents traditions, allowing understanding and approaching others (

Ahmed 2018;

Benton 2018;

Bowden 2018;

Griswold 2018;

Salcedo Ramos 2018;

Sharlet 2018). According to

Eilers (

1994), one of the theological dimensions of communication, Revelation (considered as a collection of revealed facts that come from God and that pass from one person to the other), is understood as a form of dialogue. According to the author, from the first page of the Bible, God is a communicating God. However, this self-communication extends into a dialogue with human creatures whom he created in his image. The communicative and journalistic dimension takes place in two ways: in the passing of a revealed information and truth that has to be communicated and also in the revelation understood as an interpersonal encounter. In this sense,

Eilers (

1994),

Soukup (

1983), and

O’Collins (

1981) emphasised that “God is not only revealing truth as something of him, but he is revealing himself, understood as a person to person, subject to subject, I to Thou encounter”.

O’Collins (

1981) also highlighted the effect of this revelation, the “saving power” of it. These described dimensions of Revelation analysed by the mentioned authors show the alignment of these theological scripts with journalism, particularly its aim and functions. Revelation is seen here as a synonym for communication, most precisely as a theology of communication. Journalism as a practice relies on a messenger and draws in narration. In Christian tradition, God is seen as a messenger with a desire to self-communicate (in the beginning, there was the Word). While journalism answers the need of a public to be informed, the theological scripts respond to the need of scribers to expand a message they have received. Thus, the aim of this investigation is to discover if narrative journalism could have this function, understand how it presents religion, conceptualise the influence that digital media has on this coverage, and outline the characteristics of a narrative journalist who covers religious issues. However, this research addresses the mentioned questions from the journalistic and journalists’ approach, aiming to point out some initial evidence of this possible relationship between literary journalism and interfaith dialogue. This in-depth journalistic approach has been chosen for this stage of the research to first analyse the content of the genre and discover the role of religions in it. Future research may confirm with evidence from audiences, adherents of different traditions, and religious leaders if this genre could be considered a tool for interreligious dialogue. This research introduces and contextualises the issue, giving some first results on the content and coverage of religions in the described kind of media. It does not present evidence of readers of literary journalism engaging with several religious traditions. It is a matter that could also be addressed in coming times.

According to

Grung (

2011), interreligious dialogue is defined as organised encounters between people belonging to different religious traditions, but it is also a field that addresses the premises for and the content of such organised encounters. So, this research is not about encounters caused by literary journalism but about how this genre could contribute, through knowledge, to make the premises a reality.

The selected sample is made up of three magazines dedicated to narrative journalism in three contexts that, at the same time, are spaces where migratory phenomena take place (

Ares 2017) and where there is also an increase in diversity: Spain, Mexico, and the United States. The corresponding analysed publications are

Jot Down,

Gatopardo, and

The New Yorker. These magazines have different origins, seeing as the first is a digital native, and the other two made the leap from paper to the Web. Additionally, their periods of existence are also different.

Jot Down was created in 2011,

Gatopardo in 2001, and

The New Yorker in 1925. These divergences have been taken into consideration as elements that allow for a broader vision to be given to the research. It is also a question of studying whether the identity factors that these publications present affect the central theme that this analysis addresses. Could narrative journalism be considered a space for understanding between religions? Could this genre make visible the social function of journalism (

Pousá 2016;

Schudson 2011) in the current era? This research starts to address these questions, linking topics and spaces that, although apparently distant, seem to be a bridge to bring people closer to each other.

The contribution it could make is firstly, the existent relation between both fields: literary journalism and religion. The research fits in the field of media and religion, and the reciprocity they have, since both spaces influence the other (

Campbell 2018;

Hoover and Lundby 1997). Specifically, in this field, the present research highlights literary journalism dynamics and format for presenting religion. For religious scholars, this perspective could be enlightening; it could open a debate on how literary formats shape religion in modern society. In this sense, literary journalism presents a very unique way to cover religion. It is a genre that, breaking all digital media rules, has been successfully adapted to the digital world (

Sabaté et al. 2018a). It follows high-quality standards, which is a rigorous process of elaboration that is distinguished by always giving voice to every part involved in a story (

Restrepo 2019;

Albalad 2018;

Griswold 2018).

Unsurprisingly, the Constitution of the United States, one of the countries in which this genre has been developed the most, have religious freedom and freedom of the press and freedom of expression at the same level in the First Amendment (

Sharlet 2014).

2. State of the Art

First of all, the divergences that the concept of narrative journalism generates must be highlighted. Up to 14 different designations of the genre have been found (

Albalad 2018;

Caparrós 2015;

Sharlet 2014;

Marsh 2010). For

Wolfe (

1973), it was “new journalism”; for

Capote (

1965), it was the “non-fiction novel”. The

National Endowment for the Arts (

1980) decided to call it “creative non-fiction”, which is a description that was seen as bureaucratic and that became “narrative non-fiction”, although at the same time, this concept was branded obtuse (

Sharlet 2014). Franklin defined the form as “non-fiction story” (

Franklin 1986) and “narrative journalism” (

Franklin 1996), until

D’Agata and Tall (

1997), paying homage to Montaigne, claimed that it was a “lyrical essay”.

Sims (

1996) and

Sharlet (

2014) considered it “literary journalism”,

Kirtz (

1998) considered it “long-form journalism”, while

Hartsock (

2000) called it “narrative literary journalism”.

In 2012, Boynton redefined and adapted it to the contemporary era, baptising the genre as “new new journalism”. At present, and because it is identified with a social movement that opposes postmodern immediacy (

Mattelart and Mattelart 1997), the term “slow journalism” has appeared (

Barranquero-Carretero 2013). In Latin America, all of the aforementioned are considered “crónica” (feature), which is a name that, according to

Caparrós (

2015), already carries implicit connotations of its characteristic temporality. For the author, “a crónica is very specifically an always failed attempt to capture the fugitive character of the time in which one lives” (

Caparrós 2015). However, he himself decided that this concept is too ambiguous and overused, and that a word he considered more audacious, “lacrónica”, best describes the genre.

Although the rise of narrative journalism in the contemporary era can be traced back to New York in the 1960s (

Sharlet 2014;

Weingarten 2013), through authors such as Tom Wolfe, Jane Grant, Jimmy Breslin, or Gay Talese, the first work to be considered narrative journalism is

A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe, published in 1722 (

Herrscher 2012;

Chillón 1999). However, other authors such as

Sims (

1996) or

Bak and Reynolds (

2011) detailed certain references previous to the aforementioned date. Another example is the case of

Dingemanse and de Graaf (

2011), who spoke of the Dutch pamphlets of the 1600s as a tributary of narrative journalism, or

Albalad (

2018), who put forth the Chronicles of the Indies as a still older antecedent of the genre. For

Puerta (

2011), the origin could be placed in the Book of Genesis, and even in Mesopotamia or in the discovery of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Other influences of narrative journalism are the realistic novels of Zola, Balzac, and Dickens (

Sharlet 2014;

Herrscher 2012) and Shakespeare’s plays (

Albalad 2018;

Herrscher 2012). Whitman and Thoreau are considered the architects of North American narrative journalism, which was developed during the US Civil War in Walden Pond. Whitman sought his references in what he considered to be the best gathered experiences of humanity: The Old and New Testaments, Homer, Aeschylus, or Plato (

Sharlet 2014).

Authors who analysed the historical evolution of narrative journalism include

Bak and Reynolds (

2011),

Chillón (

1999),

Herrscher (

2012) and

Albalad (

2018). Except for the first two, the rest are from the school of thought that studies narrative journalism from the Ibero-American point of view. To this group, we can add

Angulo (

2013), who was dedicated to the analysis of the gaze and immersion in this genre;

Palau (

2018), who examined it in its various applications on specific issues, such as migration;

Puerta (

2019), who studied the work of Alberto Salcedo Ramos, as well as

Palau and Cuartero Naranjo (

2018), who compared the genre in Spain and Latin America. These authors revolve around the Gabriel García Márquez Ibero-American Foundation for New Journalism. As part of it,

Albalad and Rodríguez (

2012) dedicated themselves to the study of digital narrative journalism.

In the English-speaking context, the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies focusses on what it calls literary journalism and on its digitisation. This group is made up of authors such as

Sims (

1996),

Hartsock (

2000),

Berning (

2011), or

Weingarten (

2013).

Jacobson et al. (

2015) wrote about the digital resources of slow journalism.

Neveu (

2016) focussed on the business of digital narrative journalism, while authors such as

Wilentz (

2014) studied the figure of the digital narrative journalist and their skills.

Le Cam et al. (

2019),

Cohen (

2018),

Sherwood and O’Donnell (

2018), and

Johnston and Wallace (

2016) studied the working conditions of journalists following digitisation and agreed on journalism being an identity rather than a profession. In the field of religion,

Díez Bosch (

2013) analysed the profile of journalists who specialised in religion, specifically in Catholicism. The author pointed out that knowledge is what makes journalists consider themselves specialised in this subject, regardless of the publication for which they write.

Carroggio (

2009),

La Porte (

2012),

Arasa and Milán (

2010),

Eilers (

2006),

Wilsey (

2006), and

Kairu (

2003) also dealt with this profile.

Cohen (

2012) did so in the case of the coverage of Judaism.

Within the English-speaking field, this analysis also focusses on authors who have analysed some aspect of the publications that are part of the sample. This is the case of

Yagoda (

2000),

Kunkel (

1995), or

Thurber (

1957), who are the authors with the most material produced specifically about

The New Yorker.

Although focussed on narrative journalism and its digital aspect, this study does not exclude authors who focus on digital journalism. In 2001,

Communication et langages published two articles that identified the characteristics of cyber journalism, by

Cotte (

2001),

Jeanne-Perrier (

2001), and

Masip et al. (

2010), which coincided with those written by

Micó (

2006). Specifically, the author (

Micó 2006) detailed the characteristics of the style of digital journalism as well as its properties. For

Díaz Noci and Salaverría (

2003), digital text is deeper rather than long, but affirm that depth should not influence comprehension.

Larrondo (

2009) highlighted hypertextuality as the most outstanding feature in the construction of digital discourse and pointed out that reporting is the most flexible genre for adapting to digital journalism.

Herrscher (

2012),

Chillón (

1999), and

Vivaldi (

1999) also focussed on this genre as being the most relevant in narrative journalism.

Berning (

2011) reiterated that reporting is the most malleable genre for the digital space, and also studied hypertextuality. For the author, narrative journalism was already hypertextual before the digital era, since detailed narration and scene by scene description (

Wolfe 1973) are already links that lead to other dimensions of the narration. The risk that

Herrscher (

2014) saw in digital hypertexts is that the reader can lose the narrative thread.

Rost (

2006),

Deuze (

2011), or

Pavlik (

2001) have studied other phenomena linked to digitisation, such as the interactive process or participation, which are outputs that

Benton (

2018) saw as applicable to narrative journalism.

Based on this genre, this study also expands on its link with existing literature on the mediatisation of religion and interfaith dialogue. The definition of mediatisation used is that established by

Hjarvard (

2011). The concept of mediatisation itself captures the spread of technologically-based media in society and how these media are shaping different social domains. In this sense, the urgency of the term deep mediatisation is also remarkable, describing a new and intensified stage of mediatisation caused by the wave of digitisation (

Hepp et al. 2018). The mediatisation of religion (

Hjarvard 2011) defines the process in which media represents the main source of information about religious issues and in which, at the same time, religious information and experiences become moulded according to the demands of popular media genres (

Lövheim and Lynch 2011).

Hjarvard’s (

2011) theory argues that contemporary religion is mediated through secular and autonomous media institutions and is shaped according to the logics of those media. For

White (

2007),

Sumiala (

2006),

Lövheim and Linderman (

2005), the reciprocity between the media and religion is evident, since both spaces influence each other. It is also explained in this way by

Hoover and Lundby (

1997),

Sumiala et al. (

2006), or

Zito (

2008). For

Hoover and Clark (

2002), the paradox is that people practice religion and speak of the sacred in an openly secular and inexorably commercial media context. The media determines religious experience and defines the sacred, as well as the lines between “us” and “them” (

Knott and Poole 2013;

Couldry 2003;

Couldry 2000).

Lövheim (

2019) focussed on the role of identity and gender determined by this mediatisation of religion.

Candidatu et al. (

2019) analysed it in the diaspora situation of young migrants.

In this study, the concept of dialogue is taken into account.

Merdjanova and Brodeur (

2011) pointed out that narration is one of the seven synonyms of dialogue; that is, it is one of the forms of verbal exchange between humans, together with conversation, discussion, deliberation, debate, interview, and panel. For

Braybrooke (

1992), one of the ground rules of intercultural and interreligious/interfaith dialogue is that it takes time, because it implies trust, continuity, and patience, which are conditions common to the development of narrative journalism. At the same time, dialogue is one of the characteristics that

Wolfe (

1973) specified as a norm for a text to be considered narrative journalism. On the other hand,

Eilers (

1994) analysed the theological dimensions of communication, especially Revelation, which he treated as a form of dialogue.

Abu-Nimer and Smith (

2016) affirmed that interreligious and intercultural education are not a single curricular item; they need to become an “integral part of formal and informal educational institutions”.

In this situation, the technique of storytelling (

Salmon 2008) appears as a space for the expression of one’s own identity and shows the effectiveness of what in psychology is called narrative therapy (

Payne 2002). An experience that proves this hypothesis is the existence of initiatives such as MALA (Muslim American Leadership Alliance), which gives space to young American Muslims to explain their experiences, calling for the empathy of people of their same profile, but also that of people with different profiles. Thus, narrative emerges as dialogue (

Merdjanova and Brodeur 2011). According to

Hartsock (

2000), good storytelling involves the reader, activates their neural circuits, and helps to captivate them.

Salmon (

2008) warned of the risk of telling stories about current events. According to him, the art of storytelling can become the art of manipulation. This is discussed by

Zito (

2008) and

Sharlet (

2014), who made clear that every fact is both real and imaginary from the moment it passes through the lenses of perception and imagination of a journalist’s memory. For

Sharlet (

2014), “the literary journalist needs to be loyal only to the facts as best as he or she can perceive them”.

Buxó (

2015) highlighted the importance of taking into account the symbolic function of language. For this reason,

Sharlet (

2014) emphasised that “narrative journalism is not the product of a technique but the documentation of a tension between fact and art”.

Sharlet (

2014) agreed with

Sims (

1996) in that it deals with the art of facts, art versus anti-art, belles-lettres versus the five Ws, literary piety versus ruthless journalism.

Maybe the distinction is this: Fiction’s first move is imagination, non-fiction’s is perception. But the story, the motive and doubt, everything we believe—what’s that? Imagination? Or perception? Art? Or information? D’Agata achieves paradoxical precision when he half-jokingly proposes a broader possibility: the genre known sometimes as something else.

Narrative journalism emerges as a possible call to understanding and empathy (

Griswold 2018;

Salcedo Ramos 2018), and arouses emotions (

Salmon 2008) that contrast with journalistic information. Could this effect be achieved by means of a collection of data? Do readers simply want to receive information, or do they want to feel an experience? (

D’Agata 2009). The description of the genre using the techniques that

Wolfe (

1973) and

Sims (

1996) specified gives an answer to this question. The former speaks of the use of the first and third person, scene-by-scene construction, dialogue, and exhaustive detail.

Sims (

1996) referred to the same, calling it structure, rigor, voice, and responsibility. However, he adds immersion and symbolic realities (

Buxó 2015), the equivalent of

Wolfe’s (

1973) attention to detail, elements that are presented as small truths and metaphors of daily life explained with literary techniques that allow for them to be converted into stories (

Sharlet 2014).

For

Didion (

1979), from an anthropological perspective, religions can be considered stories that society tells in order to live. The dilemma raised by

Sharlet (

2014), whereby the only essential truth of narrative journalism is the perfect representation of reality, is emphasised in this aspect. The dilemma is the same as that of religions, which makes this genre the most appropriate to document them (

Sharlet 2014). The author pointed out that understanding religions is key to understanding narrative journalism, because both explain stories and share the same paradox, the same dilemma; so, according to him, the problems inherent in talking about religions are linked to the development of narrative journalism. They share essential reality, the impossibility of representing reality, at the same time as the desire to explain it to improve the world.

Among all the diverse approaches to narrative journalism, there are some authors that better suit the data and research questions that this investigation sets out. The conditions that Tom

Wolfe (

1973) outlined for considering a text narrative journalism (which are scene-by-scene construction, realistic dialogue, status details, and an interior point of view) are reflected in the analysed texts and highlighted in the interviews carried out in this study. The evolution that narrative journalism has had according to the results obtained by this research are aligned with

Sims (

1996),

Herrscher (

2014), and

Albalad (

2018).

Berning’s analysis of digital narrative journalism is described by the practice of interviewed journalists and, again, in the analysed texts. The research also takes the perspective of Jeff

Sharlet (

2014), linking narrative journalism and religion, and highlighting the symbiotic role they have with each other.

3. Materials and Methods

The methodology for developing this research is based on in-depth interviews (

Voutsina 2018;

Elliott 2005;

Johnson 2002) and content analysis (

Van and Adrianus 2013). These methodology authors were chosen for several reasons that aim to contribute to the rigour and scientific approach of the presented research. First of all, the four mentioned authors have a vast and consolidated set of publications about the mentioned techniques in social research, so they present them in different backgrounds and contexts and obtaining diverse kind of results depending on the objective of each research. For instance,

Voutsina (

2018) and

Johnson (

2002) thought about different types of in-depth interviewing and the different possibilities of results that the researcher can obtain according to several factors. Specifically,

Voutsina (

2018) focussed on semi-structured interviews, which are the kind of interview carried out in this research.

Elliott (

2005) has been chosen because of the innovation of his approach. The author used narrative as a tool to explore the boundaries between qualitative and quantitative social research.

Van and Adrianus (

2013) is a referent by his specific analysis of the news discourse. So, these are authors that help us fit our method on their contributions and remain aware of the pros and contras of each technique. The publications considered are also from different moments during the last two decades, so the evolution that these techniques may have had has also been taken into account. These are also techniques and authors that have been used in similar research and by authors investigating in similar fields. The chosen authors are also featured for highlighting the ethical aspects of its methodology and taking them diligently into account.

The in-depth interviews were conducted with 37 professionals and experts in narrative journalism, and linked to the publications that are part of the sample. All of them accepted being quoted and mentioned in this research. As mentioned in the introduction, this research includes the journalistic approach of the issue, so future stages of it would include evidence from audiences and people engaged in religious traditions and religious leaders. The total number of interviews is 38, because Robert Boynton was interviewed twice. The in-depth interviews have made it possible to provide context and have helped understand the attitudes and motivations of the subjects (

Voutsina 2018;

Elliott 2005;

Johnson 2002). The list of in-depth interviews conducted for the development of this research include the following:

Jacqui Banaszynski, editor of the Nieman Storyboard (Harvard University)

Joshua Benton, director of the Nieman Lab (Harvard University)

Carla Blumenkranz, online director of The New Yorker

Mark Bowden, writer and narrative journalist

Robert Boynton, journalist at The New Yorker (interviewed in 2014 and 2018)

Nathan Burstein, managing editor of The New Yorker

Joshua Clover, professor of non-fiction writing (University of California, Davis)

Lauren Collins, journalist at The New Yorker

Ted Conover, freelance writer and collaborator at The New Yorker

Rubén Díaz, associate director of Jot Down

John Durham Peters, professor of media studies at Yale University

Carles Foguet, communications director of Jot Down

Ángel Luis Fernández, managing director of Jot Down

Zoe Greenberg, long-form reporter at The New York Times

Eliza Griswold, journalist at The New Yorker, expert in religion issues. Pulitzer Prize 2019

Leila Guerriero, editor of Gatopardo

Roberto Herrscher, collaborator of Gatopardo

Ricardo Jonás, co-founder of Jot Down

Carolyn Kormann, editor of The New Yorker

Jon Lee Anderson, journalist at The New Yorker

Ramón Lobo, freelance journalist, writer for Jot Down

Larissa Macfarquhar, journalist at The New Yorker

Monica Račić, multimedia editor at The New Yorker

Evan Ratliff, journalist, co-founder of The Atavist Magazine

Felipe Restrepo, director and editor of Gatopardo

William Reynolds, president of the International Association for Literary Journalism

Noah Rosenberg, director of Narratively

Carlo Rotella, freelance editor of The New Yorker

Emiliano Ruiz Parra, freelance journalist for Gatopardo

Alberto Salcedo Ramos, narrative journalist and professor at the Gabriel García Márquez Foundation for New Ibero-American Journalism

Susy Schultz, director of Public Narrative

Jeffrey Sharlet, narrative journalist specialised in religion, professor at Dartmouth University

Norman Sims, former president of the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies

McKenna Stayner, journalist at The New Yorker

Gay Talese, writer, journalist at The New Yorker and father of new American journalism

Marcela Vargas, digital editor of Gatopardo

Julio Villanueva Chang, director of Etiqueta Negra

The choice of interviewees is based on their career, experience, and links to the publications studied. In addition, people in different positions and from different generations and political views have been interviewed in order to obtain a global view on the subject, while obtaining results based on the symmetry of criteria and gender balance. The interviews were carried out in person (23), by telephone (5), by video conference (8), and by email (2). These conversations took place in four countries: Spain, the United States, Mexico, and Canada. The researchers travelled from Spain to the United States and Canada.

The witness and arguments expressed by experts and professors who are working in other institutions are used here to support and complement the opinions of those who express the vision of the analysed media. It has also been considered that external views from people working in prestigious institutions would enrich and make the research more critical.

The in-depth interviews have been useful for this analysis to confirm, check, and contrast the results obtained in the content analysis. The different explanations, opinions, and witnesses helped the team understand and give context to data, make it richer, and also clarify the differences and similarities among the media analysed. In this sense, and according to

Voutsina (

2018), in-depth interviews help collect in-depth data and approach the global data reflexively; with this technique, the discourse benefits from added nuances. The contact with the lived experience is also an added value of this technique (

Johnson 2002).

The content analysis was developed over 75 articles in two research phases. The first was made up of the analysis of 45 articles, 15 of each of the three publications selected for the sample. Each of them comes from a different section of each publication and deals with different themes. This first phase served to gather global results in the first instance, as well as test the questionnaire created to carry out the analysis. This questionnaire is made up of four parts: identification, form, content, and audience. The first places the piece according to its section, author, and title. In the second part, the elements, report, and structure of each piece of news are taken into account, while also considering the presence and appearance in both digital form and on paper. The fields that are specified correspond to the elements that are to be analysed: subtitles, multimedia complements, images, positioning and extension strategies, manifested in the number of scrolls and pages on paper. Regarding the content, the questionnaire delves into narration. For this reason, the subject and tense are identified. The audience is treated based on the interactions with each of the pieces on the social networks on which they have been published. The use of content analysis (

Van and Adrianus 2013) as a technique for this research is supported by previous studies on narrative and digital journalism, such as those by

Jacobson et al. (

2015), and

Domingo and Heinonen (

2008). Authors such as

Gillespie (

2015),

Guo (

2014), or

Larssen and Hornmoen (

2013) also use this technique.

Once the first part of the content analysis was completed, the second and more specific part was devoted to the study on the coverage of religions in the media analysed. The same evaluation sheet was used, although it was extended with a new section titled “Religion”. It includes nine new fields that analyse the pieces in order to answer specific questions about religion in the publications. In this sense, what is detected is: the faith to which each story refers, the role of religion in the piece, the tone used to treat it, the presence or absence of leaders, the presence or absence of quotes by these leaders, and the existence of informative and substantive elements on the faith in question. The questionnaire also studies if the piece promotes prejudices or helps eliminate them. This last part of the questionnaire has been applied following the example of media analysis carried out by the

World Association for Christian Communication (

2017) in its research on the coverage of migration in Europe, projects in which the authors of this article have collaborated.

In this second part, 30 articles were evaluated, 10 from each of the publications analysed. The selection of these was carried out with a basic criterion: the appearance or coverage of religions. None of the magazines analysed has a section dedicated to religion; therefore, the articles studied were located and selected using the search engines of the magazines’ digital versions through the keyword “religion”. The criterion of currency prevailed; for this reason, the 10 most recent articles from each of the magazines were chosen at the time of making the selection, in April 2019.

Thus, taking into account the first and second phase of content analysis for this research, a total of 75 articles were analysed, 25 from each of the publications that make up the sample: The New Yorker, Gatopardo, and Jot Down.

With the techniques carried out, the research introduces the issue of the relationship between literary journalism and religions, contextualises it, and shows how the content of this analysed genre takes into account religions—all from the journalistic approach, having analysed the content and interviewed professionals in the field. As mentioned, the possible interfaith function that literary journalism can have may be confirmed with further evidence than journalistic ones. The research decided to first study the journalistic agents of the research to better know the role and presence of religion in the literary journalism.

4. Results and Discussion

Narrative journalism is faithful to the norms of traditional literary journalism, even though it does not fulfil the characteristics established by digital journalism (

Restrepo 2019;

Sabaté et al. 2018a). One of the main challenges of this investigation is to discover if narrative journalism about religion differs from these characteristics, as well as to unravel its particularities. Firstly, it is worth noting the analysis carried out on articles in general from the various sections of the three magazines. There were a total of 45 (15 from

Jot Down, 15 from

Gatopardo, and 15 from

The New Yorker).

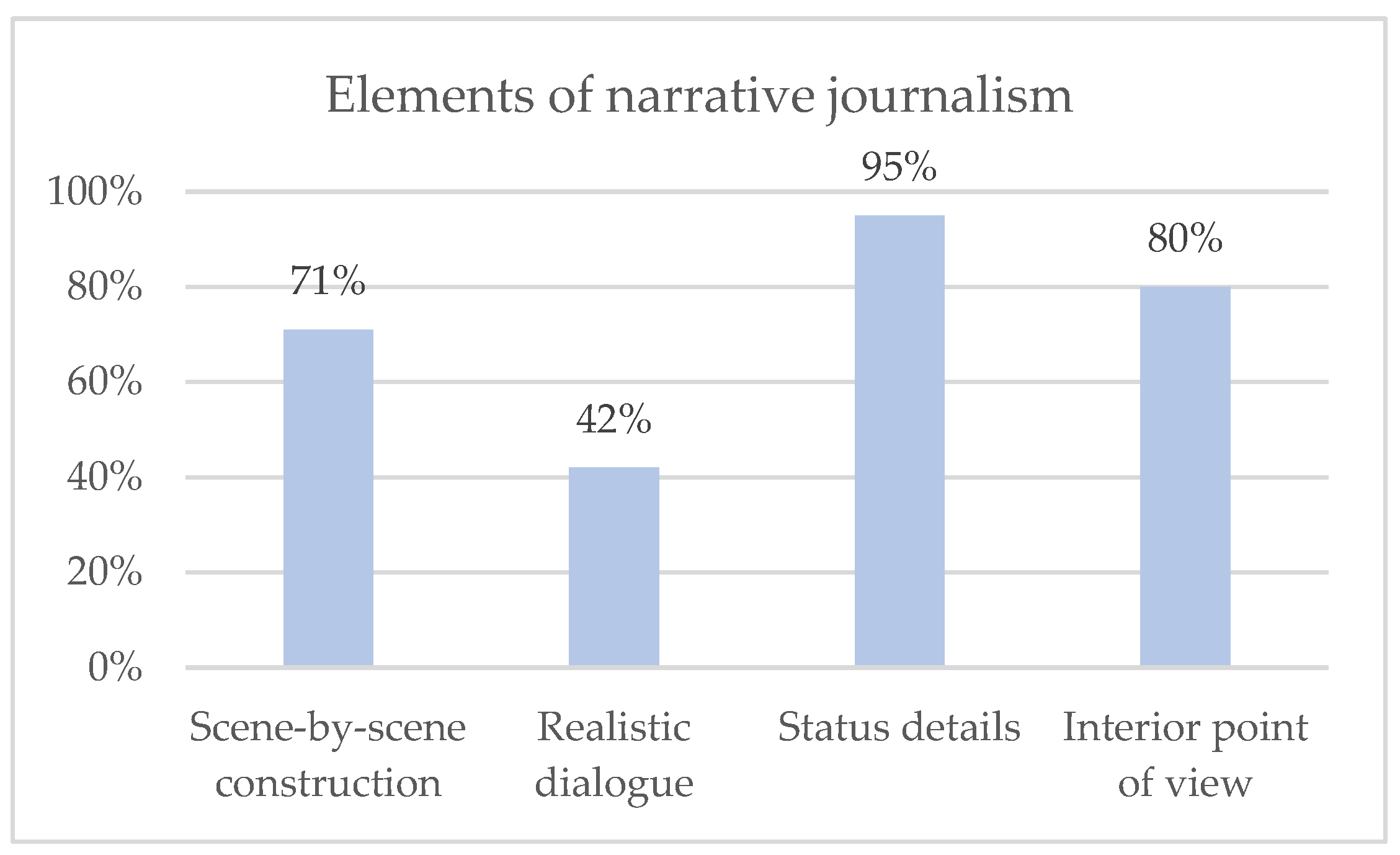

As shown in

Figure 1, all the elements of narrative journalism are present in a high degree: above 40% in all the articles analysed. In this case, the least used element is dialogue. By focusing on the articles in which religion is present, most also fit into the four categories that

Wolfe (

1973) considered necessary for narrative journalism: scene-by-scene construction, realistic dialogue, status details, and an interior point of view (

Sims 1996;

Sharlet 2014). In all the media analysed, these characteristics consistently appear in a percentage higher than 50% in articles on religion, as shown in

Figure 2.

Comparing both series of data indicates that, in general, both the global articles and those dealing with religion fulfil, to a high extent,

Wolfe’s (

1973) conditions of narrative journalism, as reiterated by

Sims (

1996). Focusing on each of the characteristics, status details are 100% present in the articles on religion, and 95% in the global articles. Regarding scene-by-scene construction, its percentage of usage is also higher in articles on religion (76%) than in global articles. Regarding the interior point of view, it is used more often in global articles (80%) than in those that address religion (76%), although the difference is minimal. The use of dialogue is higher in articles on religion (56%) than in articles on global issues (42%). This format, based on the Socratic method, incorporates the need for the reader to receive the content in a didactic way. It is based on the idea that through dialogue and encounter with the Other, people learn about this Other (

Abu-Nimer and Alabbadi 2017;

Merdjanova and Brodeur 2011). For

Volf and McAnnally-Linz (

2016), “When encounters with others go well, we become more ourselves. As people and communities, we are not created to have hermetically sealed identities.”

According to

Merdjanova and Brodeur (

2011), in addition, narration is one of the forms of human dialogue and one of the ways in which people construct their beliefs and identities. It is significant that texts on religions use the technique of dialogue more than other types of texts. It is about offering the content about religions in an understandable way, one which through the stories appeals to the presumptions that the audience may have about a specific religious group (

Restrepo 2019;

Griswold 2018).

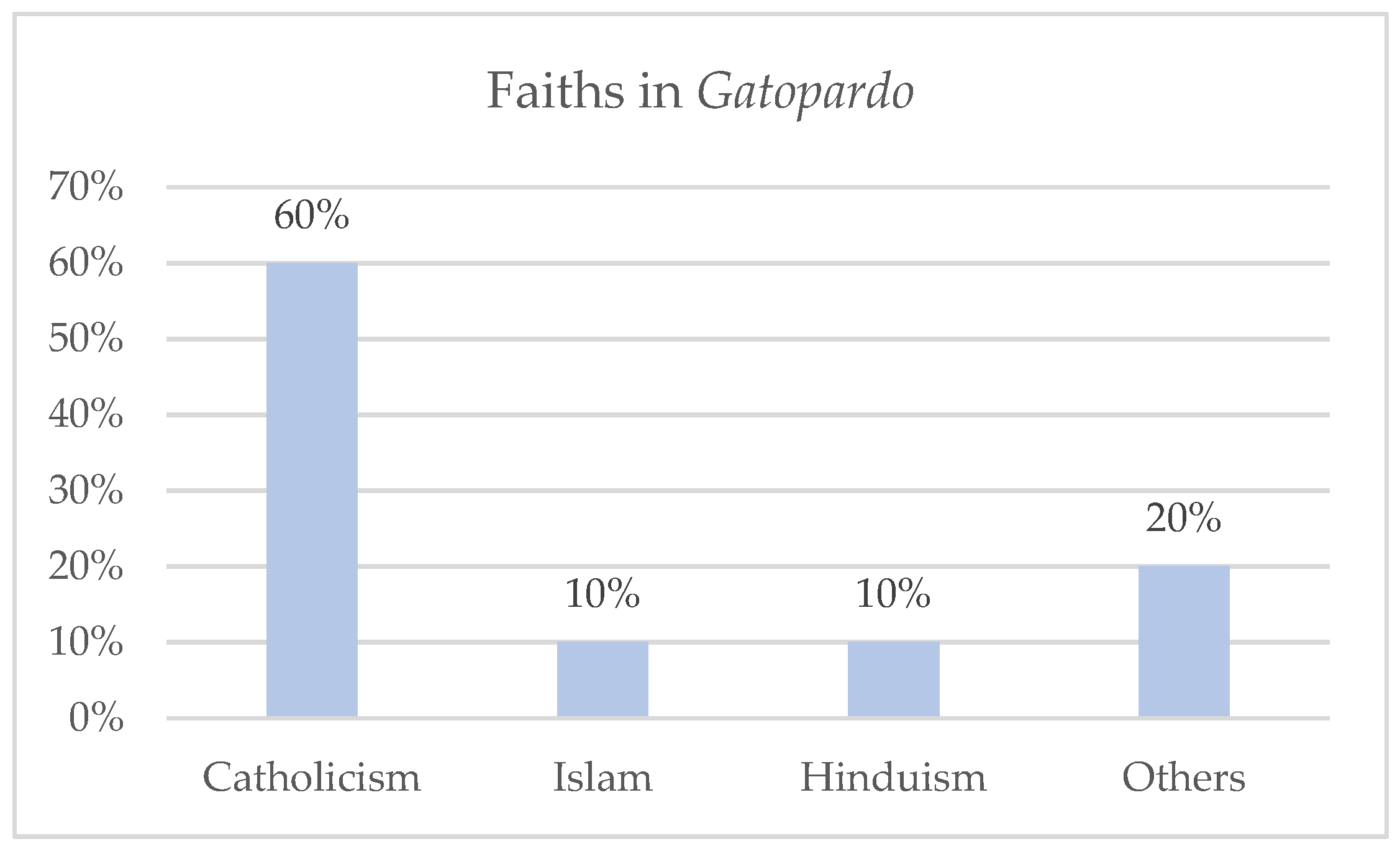

This research has also focussed on which faiths are addressed most in the narrative journalism media analysed. They are displayed in

Figure 3.

Among the total of articles analysed, Catholicism is featured most, followed by Protestantism and Islam. It is a trend that is consistent with the figures of religious self-identification indicated by data found at a global level. This research also evaluated this phenomenon (

Figure 4).

In

Jot Down, the main faith detected is Catholicism, followed by Islam and Christianity in general. When comparing these results with demographic figures, it can be seen that 67.7% of Spaniards consider themselves Catholic (

CIS 2018), and that the second most popular faith in communities in Spain is Protestantism, followed by Islam (

Observatory of the Religious Pluralism in Spain 2019). Thus, the most covered faiths in

Jot Down are also the most numerous in number of followers in Spain.

In

Gatopardo (

Figure 5), 60% of the pieces address Catholicism, 10% address Islam, another 10% address Hinduism, while 20% address other religions. In this last category, several stories are considered that address specific beliefs and spiritualities in some parts of the country. According to the National Survey on Religious Beliefs and Practices in Mexico (ENCREER/RIFREM website 2016), in the Central American country, 85% of individuals identify as Catholic, 8% identify as Protestant Christian, and 0.1% identify as other religions. In this case, the results of the articles are again proportional to the representation that these confessions have in the country of the publication analysed.

In

The New Yorker (

Figure 6), Protestantism is the predominant faith (60%) among the topics in which religion is present. It is followed in a much smaller percentage (10%) by Christianity in general, Catholicism, Hinduism, and other religions. According to Gallup (website 2017), in the United States, 48.9% identify as Protestant Christian, 20.8% identify as Catholic, 0.7% identify as Hindu, 0.9% identify as Muslim, and 1.5% identify as other religions. These figures coincide with those presented by the Pew Research Center’s Religious Landscape Study (

Pew Research Centre 2014).

In all three cases, the representation of religious faiths in the articles coincides with their presence in each of the countries of which the journals are native. The presence of religions corresponds to the national reality of each publication. This fact allows the research to detect a kind of social conscience of these narrative journalism magazines in regard to religion, and is an element that allows the investigation to sense that they may become a tool for interfaith dialogue, as they proportionally represent the faiths that are present in their surroundings. As

The New Yorker, Jot Down, and

Gatopardo covered these several confessions proportionally, their readers may be aware of their existence and reality, so they could become more informed, and thus obtain more knowledge about confessions that could be unknown for them and avoid prejudices. It is about knowledge that is predicated on promoting understanding (

Ahmed 2018). According to

Abu-Nimer and Smith (

2016), “a constructive contact with those who are different from ‘us’ requires having intercultural and interreligious competences as integral like skills in this increasingly interconnected world. In the cases of

Gatopardo and

The New Yorker, it is also worth mentioning the presence of the category of other religions, which includes the possibility that their reader base may be familiar with realities that are not as popular as other religions present in the media. This is in fact one of the particularities of this type of publication: the presence of topics that do not usually get coverage in general media (

Reynolds 2018;

Díaz Caviedes 2014;

Guerriero 2014). The term “general media” is here understood as media that covers the traditional subjects (politics, society, sports, culture) globally and looks for a wide reach, generally nowadays combining information from press agencies and pieces written by their journalists. Narrative journalism media does not present this structure. They open new spaces for representations of topics overlooked elsewhere with several techniques: free sections (not following the traditional distribution), free timing (giving journalists the time that a subject need, that could be months or years), and reporting and practising investigative journalists, not to cover the same topics that mass media covers or cover it from a new and unexpected approach (

Guerriero 2014;

Herrscher 2014).

This study also questions how topics on religion are covered following the guidelines of media monitoring analysis in accordance with the methodology of the

World Association for Christian Communication (

2017). This entity measures the rigor of media coverage of certain issues, based on the extent to which people’s freedom of expression and the different beliefs that appear in the media are respected. Among other points, it focusses on three main aspects: the presence of the people that are spoken about (in this case, religious leaders or people associated to religions), the number of quotes they publish, and the amount of background information on the subject (in this case about the religion itself). Taking this example,

Figure 7 shows the appearance of each of these elements in the stories analysed:

Generally, the three publications studied include the presence of religious leaders, statements or quotes by them, and background on the faith that is addressed in each story (a background that is linked to the high degree of status details that has been detected in the pieces about religion; see

Figure 2). Thus, in a global way, another factor may be determined that could highlight the hypothesis that narrative journalism may be a possible space to contribute to interfaith dialogue, seeing as it uses the most representative aspects that are considered for respecting the freedom of expression of the people spoken of in each story (

World Association for Christian Communication 2017).

When examining these results publication by publication, there are differences in some aspects. The presence of leaders is more evident in The New Yorker and in Gatopardo than in Jot Down, which is a publication that makes greater use of the study and analysis of background information when covering issues of religion. In relation to this aspect, there is a much smaller number of quotes in Jot Down (present in 20% of the articles studied) than in Gatopardo (70%) and The New Yorker (80%). In fact, overall, The New Yorker is the publication, among those analysed, that takes these elements into account the most.

Overall, the results show that narrative journalism articles may possibly contribute to dismantling stereotypes; 63% of the pieces examined do so. However, 23% promote them, while 10% are considered neutral. The high use of the elements of narrative journalism in these articles could be related to their ability to challenge prejudices. At the same time, following this hypothesis, and as the research would introduce in the following points, the role of the journalist could be also linked with the role of the facilitator, in the sense of becoming a kind of mediator. Nevertheless, the existence of pieces that can promote stereotypes even when using narrative journalism leads to a reflection on the education, deontology, and professional practice of the people involved in narrative journalism. Future researches considering audiences’ readings may be able to better confirm this aspect.

4.1. The Narrative Journalist that Covers Religion

Curiosity (

Restrepo 2019;

Conover 2018;

Villanueva Chang 2017), perspective, resistance (

Boynton 2018;

Lee Anderson 2018;

Guerriero 2014;

Yagoda 2000), and perfection in form (

Lobo 2018;

Sims 2018;

Collins 2018) are the main characteristics of a narrative journalist (

Sabaté et al. 2018a). These relate directly to features that correspond to the demands of narrative journalism set forth by

Wolfe (

1973) and

Sims (

1996).

Sherwood and O’Donnell (

2018) spoke of identity journalism.

MacFarquhar (

2018),

Blumenkranz (

2018),

Banaszynski (

2018),

Bowden (

2018), and

Guerriero (

2014) argued that this profile is very specialised, that it requires both learned and innate skills, and that it is developed by a “chosen few”.

Weingarten (

2013) and

Yagoda (

2000) highlighted this genre along the lines of what

Albalad (

2018) called “caviar journalism”. With digitisation, the possibility of being considered for publication in this type of media has grown (

Greenberg 2018;

Díaz Caviedes 2014), although key elements for learning the trade have been lost, such as face-to-face contact between veteran professionals and students (

Banaszynski 2018).

For

Griswold (

2018) and

Sharlet (

2018), there is a distinction between narrative journalists and narrative journalists who cover religion: the ability to put aside one’s beliefs and listen to the Other. This is one of the types of dialogue highlighted by

Eck (

1987)—the dialogue of life, which opens up the possibilities of visiting, participating, and sharing experiences with different local communities.

Sharlet (

2014) admitted that “as a writer, I practice participant observation, so, with as clear-as-can-be disclaimers—‘Look, I do not really share your beliefs…’—I’ve often joined in”. For

Griswold (

2018), “it is about suspending one’s point of view in order to encounter the Other”. According to the author:

In covering religion, the skills are the same as covering any ideology. So, as a reporter, one has to be able to suspend one’s point of view in order to encounter people who are really different. People who believe different things, who believe that certain people are going to hell, who may have different political views that for them are not political, they are religious. It is important as a reporter to be able to sit down and listen to all those people at great length, without passing judgement or feeling threatened by differences.

A sensibility is detected here beyond the characteristics that define narrative journalists. This sensibility leads the research to introduce the relation between the narrative journalist with the figure of the dialogue facilitator. According to

Abu-Nimer and Alabbadi (

2017), the profile of a dialogue facilitator could be comparable to the guide of a journey, and specify that “no one can walk the path for another person, but a guide can make the journey meaningful and enjoyable, despite the challenges and rocky areas on the trail”. For them, the facilitator does not direct, but makes the process of understanding possible.

Abu-Nimer and Alabbadi (

2017) also pointed out that a facilitator is impartial, although aware that the reality they interpret is based on their own subjectivity. Therefore, they are at a certain distance from the actors and design the way for them to understand each other effectively.

Following this description and taking into account the definition of the narrative journalist of some authors (

Sabaté et al. 2018a) and interviewees (

Boynton 2018;

Griswold 2018;

Sharlet 2018), the role of the narrative journalist who covers issues of religion may be compared to the role of a facilitator. With curiosity, a gaze of their own, excellent writing form, and resistance (

Restrepo 2019;

Boynton 2018;

Guerriero 2014), this type of professional is also able to put their beliefs, convictions, and presumptions on hold, and position themselves face-to-face with an Other who is different (

Griswold 2018;

Lee Anderson 2018;

Lévinas 1985;

Buber 1923;

Stein 1916), in order to listen to them, understand them, and make themselves understood.

The importance of the use of the first person in this type of narrative journalism is detected in this aspect. This technique, which is ground-breaking in the face of traditional journalism, defines narrative journalism (

Reynolds 2018;

Sims 2018). For

Sharlet (

2014), when covering religions, this aspect becomes relevant, because according to him, literary journalism deals with perceptions, and a narrative journalist must be faithful to facts to the extent that they perceive them. In religion, “things unseen” are often documented; therefore, the demand for transparency in the process is even higher. In this regard, the research must take into account the symbolic function of language and the role that it plays in the production and reception of this type of texts (

Buxó 2015). The author (

Sharlet 2014) gave Whitman as an example, and outlined how this writer explained his method transparently and in the first person.

Schultz (

2018) defended this demand to explain to the reader how the facts have been established. For

Clover (

2018), the use of the first person creates the author’s own style. However, according to

Lobo (

2018), this element is a clear distinction between narrative journalism in Latin America and North America, seeing as in the United States, the first person is more normalised in narrative journalism texts. It is also detected in

Gatopardo and more in the two American magazines than in

Jot Down. In this sense, Gay

Talese (

2019) was sceptical towards the idea that the emergence of digital space contributes to journalists’ transparency.

I practice the journalism of ‘showing up’. It demands that the journalist deal with people face to face. Not Skype, no emailing back and forth—no, you must be there. You must see the person you are interviewing. You must also ask the same question a few times, to be sure the answer you are getting is the full and accurate one.

4.2. A Digitally Non-Digital Journalism

Talese’s (

2019) scepticism is not exceptional, and shows the relationship that this genre has with the digital world. The knowledge of digital tools is not enumerated among the capabilities of narrative journalists in any of the interviews. In fact, one of the main characteristics of digital narrative journalism is the non-fulfilment of digital journalism’s rules of style and writing (

Sabaté et al. 2018b;

Albalad 2018). According to

Micó (

2006), digital writing should have: updated data, universal information, simultaneity, interactivity, multimedia, hypertext, and versatility.

Although narrative journalism takes into account updated data, it does not aim to be the first to publish it (

Restrepo 2019;

Blumenkranz 2018;

Burstein 2018;

Račić 2018;

Guerriero 2014;

Herrscher 2014). “We want to tell stories through an approach that has never been addressed before, even they take longer time”, affirmed Leila

Guerriero (

2014). In this sense, Marcela

Vargas (

2014) said that “the spirit of

Gatopardo is not ‘breaking news’”. Global information is present in this type of journalism, which ends up dealing with major issues (

Restrepo 2019;

Salcedo Ramos 2018;

Guerriero 2014). On the other hand, the media outlets in which narrative journalism appears are not mainly interactive. They use some means of contact with the public, such as social media (

Restrepo 2019;

Díaz Caviedes 2014;

Foguet 2014), which measure the temperature of the evolution of topics. However, the audience does not intervene in the production of the texts (

MacFarquhar 2018;

Stayner 2018;

Foguet 2014;

Ruiz Parra 2014). In relation to the use of multimedia resources, both global analysis and analysis of articles on religion show that narrative journalism media do not fully exploit the possibilities of the online environment (

MacFarquhar 2018;

Ratliff 2018;

Fernández 2014;

Jonás 2014;

Vargas 2014;

Berning 2011). Of the 30 articles on religion analysed, only one uses multimedia elements. In this sense, the consideration of the concept of “immersion” (

Conover 2018;

Angulo 2013) related to the effect of multimedia elements appears as a debate. Despite all the interviewed experts considering the text to be the main way for the audience to be immersed in the story, younger generations of professionals consider multimedia elements a useful complement for the text. According to Monica

Račić (

2018), “multimedia elements have to be present to give information that the text itself does not offer and that helps audience to better understand the story”. For Roberto

Herrscher (

2014), “immersion can be only achieved by audience imagination when reading”.

This research has also looked at the positioning elements that have been used in the articles. These elements have been located in 23 of the 30 articles. However, the variety of these elements is limited. There is the use of bold text (in 11 articles), internal links (in seven articles), and links to related articles (in five articles). Therefore, digital positioning is taken into account in a subtle way.

Finally, when studying versatility, it can be seen that in this type of journalism, it is mostly present in digital format, even though it is heavily influenced by the layout, structure, and format of the paper. Digital narrative journalism texts are proof of a certain “paperisation” of the internet (

Albalad 2018;

Foguet 2014). However, they are versatile in a specific aspect: length. Eliza

Griswold (

2018) said, “I write longer than my editor would like, but the fact of not having a limit to tell the story is something hugely enjoyable”.

It should be noted, before analysing this aspect, that

Micó (

2006) also detailed the style conditions of digital journalism: accuracy, clarity, conciseness, density, precision, simplicity, naturalness, originality, brevity, variety, appeal, colour, sonority, detail, and propriety. Narrative journalism is accurate, dense, precise, and original; it has colour, sound, detail, and propriety. However, it is not concise, simple, or brief. Narrative journalism seeks literary excellence (

Kormann 2018;

Lobo 2018;

Guerriero 2014;

Herrscher 2014) and does not set any limitations that may interfere with the achievement of this goal. In this way, it develops a type of journalism that has also been called long-form (

Boynton 2018), that does not follow any canon except for that which each story requires (

Račić 2018;

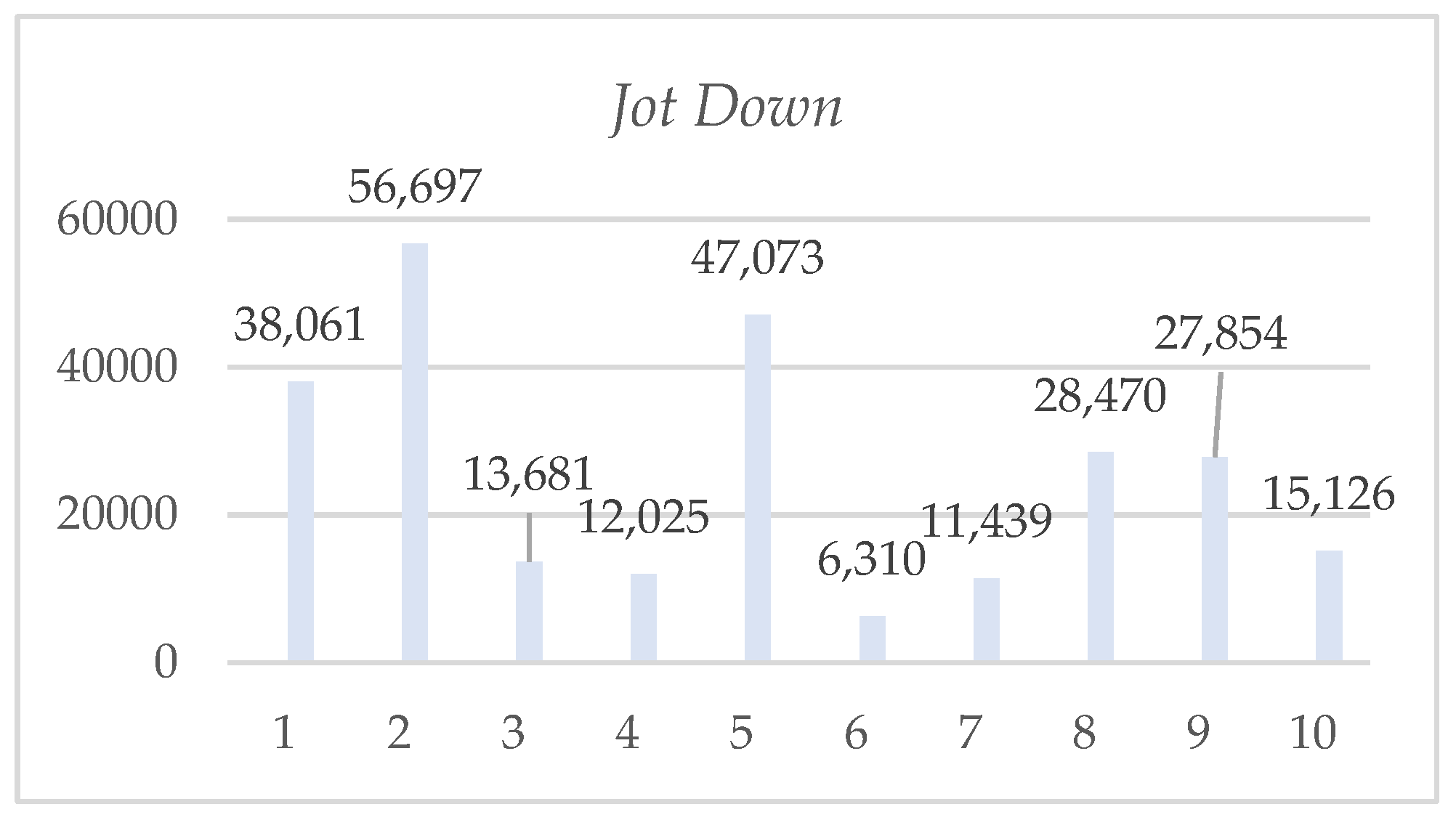

Herrscher 2014). This is displayed in the following figures (

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11) on the length of the articles that cover religion:

Similar to

Larrondo (

2009),

Díaz Noci and Salaverría (

2003) emphasised that a digital text is deep rather than long, referring to the hypertextual depth of digital articles. In this respect, the will to break with what is established in narrative journalism (

Restrepo 2019;

Reynolds 2018;

Sims 2018) is denoted once again, seeing as it is longer than it is hypertextually deep.

This unlimited length also indicates how temporal flexibility is managed in these media (

Burstein 2018;

Vargas 2014). For

Del Campo Guilarte (

2006), the productivity of technologies cannot replace human slowness and imperfections. Precisely, slow journalism is the name given to this genre, which does not prioritise immediacy of publication and grants each topic the time it requires (

Restrepo 2019;

Rotella 2018;

Guerriero 2014;

Herrscher 2014). A prior agreement is detected with a type of reader who prefers to wait to receive a product (

Sabaté et al. 2018b) that provides all the elements for understanding a story. According to Rubén

Díaz Caviedes (

2014), “these conditions are a privilege for a journalist”.

This research questions to what extent this digital disloyalty influences that narrative journalism may be introduced as a possible tool for intercultural and interreligious dialogue. It stems from the need of some communities linked to specific faiths to get out of the bubble that digital space can represent. Although

Castells (

1996) pointed out that new media technologies can contribute to the construction of networks between social groups, the creation of online communities (

Dawson and Cowan 2004) linked to religion is, in some cases, at a stage prior to maturity (

Díez et al. 2018); thus, digital dialogue between different communities is still a distant reality (

Díez et al. 2018;

Leurs and Ponzanesi 2018). One of the reasons for this is that many communities still do not consider the internet a space (

Spadaro 2014), but rather a tool or an instrument of communication, not considering the further possibilities it has. They are in the stage of “religion online”, and not yet in the stage that

Helland (

2000) defined as “online religion”. He distinguished communities that act with unrestricted freedom and a high level of interactivity (online religion) versus those who seem to provide only religious information and not interaction (religion online).

Dialogue requires conditions that are more linked to slow journalism than to digital immediacy, seeing as dialogue requires time and implies continuity, patience, and building trust (

Braybrooke 1992). According to

Abu-Nimer and Alabbadi (

2017) and

Merdjanova and Brodeur (

2011), dialogue demands a safe space for participants to be able to overcome their assumptions and question their own previous perceptions and prejudices. Dialogue also requires a facilitator to guide it. According to the interview with Jeff

Sharlet (

2018), digital space appears here as a channel that allows elements of dialogue to have greater reach, but it is not digital dynamism that is going to foster it. It is here that narrative journalism may be seen as a safe space (

Abu-Nimer and Smith 2016) in which both the dynamics and content may become adequate for creating dialogue. In fact, dialogue helps to differentiate between the person and the subject, to see the individual within a large group that can be perceived as an adversary (

Abu-Nimer and Alabbadi 2017;

Merdjanova and Brodeur 2011). This is what narrative journalism aims to do: it talks about big issues based on individual stories (

Guerriero 2014;

Herrscher 2014), distinguishes people from concepts, and calls upon the reader to understand a specific reality from a different point of view (

Díaz Caviedes 2014) that makes them reconsider their previous ideas (

Guerriero 2014;

Herrscher 2014). For Eliza

Griswold (

2018), “the key is explaining how complex people are, how complex humanity is in a way that hopefully makes it possible for people to consider the way what they thought about others before they read”. For

Berning (

2011), digitisation gives the journalists more sources for making it possible, for the audience to check and explore all the elements of a story.

In this context and taking these elements detected into account, the narrative journalist profile could be related to the role of the facilitator. These figures guide and mediate a process of dialogue that they have been a part of, suspending their own beliefs and actively listening to the Other (

Sharlet 2018;

Griswold 2018;

Abu-Nimer and Alabbadi 2017;

Merdjanova and Brodeur 2011), leaving their comfort zone and inviting readers to also leave theirs. It is in this zone that dialogue could begin and allow people to put themselves in the place of the Other and understand them.

A narrative journalist could be able to make use of literary art to carry out their task, which could be related to the facilitator’s one; this art, sown by precedents (

Abu-Nimer and Alabbadi 2017;

Merdjanova and Brodeur 2011), may reinforce the empathising effect of the stories. Examples of articles analysed showing these conditions are “La gente piensa que el obispo no es católico” (

Gatopardo. Authored by Emiliano

Ruiz Parra (

2019)) or “The renegade nuns who took on a pipeline” (

The New Yorker. Authored by Eliza

Griswold (

2019)).

To confirm if this relationship between the two professional figures and the effect that this genre may have related to interfaith dialogue, future research may point out the approach of the audience, people involved with several religious traditions and also religious leaders. The aim of this investigation has been to introduce this possible relationship, put it in its contexts, and study in-depth the coverage and presence of religions in this kind of media.

5. Conclusions

This research introduces the possibility that narrative journalism could become a tool for interfaith dialogue. The results obtained based on the methodology, content analysis (

Van and Adrianus 2013), and in-depth interviews (

Voutsina 2018;

Elliott 2005;

Johnson 2002) allow us to determine that, with the present data, the main hypothesis has been pointed out with evidences from the in-depth interviews and the content analysis carried out. Results show that it covers the different religious realities of its surroundings in a proportional and representative way, detailing how the social presence of some faiths in different geographical contexts is proportional to the appearance of these faiths in the corresponding publications.

This representation is reinforced by the fulfilment of the rights of freedom of expression and communication of these religious communities (

World Association for Christian Communication 2017). In narrative journalism publications, religion is not spoken about without first talking with religion—that is, with the protagonists of the topics that are covered. The results of the content analysis show a high presence of these agents in the stories. In addition, the high level of detail required by narrative journalism (

Sims 1996;

Wolfe 1973) makes the background have an outstanding presence and effect in the articles on each faith. This background completes the information that the protagonists give and allows a better understanding of the different faiths. For the most part, all these reasons lead narrative journalism articles that cover religious topics to create conditions that have the potential to challenge religious stereotypes. However, the present investigation takes a very specific approach that shows the dynamics of literary journalism covering religion from the journalistic approach. Future related research may also consider evidence related to the religious leaders and audience.

In the same sense, the way that narrative journalists practice their profession is also a factor that could point out narrative journalism as a possible tool for interreligious dialogue. This study has detected that a narrative journalist’s abilities, processes, and knowledge could be related with those practiced by dialogue facilitators. They appear as the key figure in a process of understanding. They experience this process in each story they cover, leaving aside their prejudices (

Griswold 2018;

Sharlet 2018) and listening actively: the two key actions of dialogue according to (

Abu-Nimer and Alabbadi 2017).

Finally, the research points out how narrative journalism and dialogue require a slow rhythm that is detached from the speed of the online space (

Braybrooke 1992). In this sense, the digital disloyalty of narrative journalism adapts to the rhythm and dynamics that dialogue requires, since this genre appears as a safe space for understanding in the midst of postmodern acceleration (

Durham Peters 2018). Thus, digital space is simply a platform that can increase the reach of dialogue, but due to its rhythm, it does not contribute to it taking place. The main contribution could be made by narrative journalism, with its characteristics, and by narrative journalists, through the practice of their profession. They try to get the audience out of their comfort zone (

Abu-Nimer and Alabbadi 2017), to go beyond their prejudices (

Restrepo 2019;

Griswold 2018;

Sharlet 2018), and position themselves in this awkward space in which dialogue could take place (

Merdjanova and Brodeur 2011). Future research may show, in this sense, the effect that this genre has on audience and the approach from people engaged with religions and from religious leaders in considering it a possible element to contribute to interfaith dialogue. It is about society feeling addressed in the encounter with the Other (

Volf and McAnnally-Linz 2016;

Torralba 2011;

Lévinas 1985), based on the narration and revelation of stories (

Eilers 1994). At a time of mass migration (

United Nations Refugee Agency 2018;

Ares 2017) and the rise of fake news (

Quandt and Schatto-Eckrodt 2019) and hate speech (

Parekh 2019;

Gagliardone et al. 2015), the tools that promote and contribute to this encounter (

Volf 2015), such as narrative journalism, might be a guarantee for the future.