“Whoever Harms a Dhimmī I Shall Be His Foe on the Day of Judgment”: An Investigation into an Authentic Prophetic Tradition and Its Origins from the Covenants

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. A Mutawātir Dictum in the Covenants

“Whoever afterwards commits an injustice towards a protected person by breaking or rejecting the covenant, I shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment from among all the Believers and the Muslims.”

“wa man ẓalama ba‘d dhalika dhimmīyyan wa naqaḍa al-‘ahd wa rafaḍahu kuntu khaṣmahu yawm al-qiyāma min jamī‘ al-mū’minīn wa al-muslimīn kāffatan.”

“Whoever falls short of upholding the conditions [of this covenant], goes contrary to them, or does not abide by my instructions, and so, as a consequence mistreats a protected person, I shall be his foe in front of Allah on the Day of Judgment and so will all the believing men and women in their entirety.”

“wa man naqaḍa wa ‘amila bil-khilāf wa lā sami‘a kalāmī wa ẓalama dhimmīyyan anā akūn khaṣmahu quddām Allāh yawm al-qiyāma wa jamī‘ al-mū‘minīn wa al-mū’mināt kāffatan ajma‘īn.”

“wa man naqaḍa wa ‘amila bi-khilāf al-shurūṭ [instead of bil-khilāf] wa lā sami‘a kalāmī wa ẓalama dhimmīyyan akūn khaṣmahu yawm al-qiyāma [instead of anā akūn khaṣmahu quddām Allāh yawm al-qiyāma].”

“Whoever reads this writ of mine or to whoever it is read out to and he alters or changes anything of what is in it, upon him shall be the curse of Allah and the curse of those who curse from among the angels and all of mankind. Such a person is free from my protection and intercession on the Day of Judgment and I am his foe. Whoever is my foe is the foe of Allah, and whoever Allah has declared as foe goes to hell.”

“wa man qarā’ kitābī hadha aw quri’a’ ‘alayhi wa ghayara aw khālafa shay’ān mimmā bihi fa-‘alayhi la‘natu Allāhi wa la‘nat al-lā‘inīn min al-malā’ika wa al-nās ajma‘īn wa huwa bari’un min dhimmatī wa shafā‘atī yawm al-qiyāma wa anā khaṣmuhu wa man khāṣamanī fa-qad khāṣama Allāh wa man khāṣama Allāh fa-huwa fī al-nār.”

“Whoever commits an injustice towards a protected person, even if it by an atom’s weight, Allah shall not bless that which is in the possession of his right hand nor his lot and fortune, and I shall be his foe [literally, an advocate against him] on the Day of Judgment. Whoever harms them, harms me, and he who wrongs them wrongs me, and I shall be his foe on the Day of Reckoning and punishment, the day in which he will enter his grave alone.”

“wa man ẓalama dhimmī mithqāl dhara fa-lā bārak Allāhu lahu fī mā malakat yamīnuhu wa fī ṣaybihi wa naṣībihi wa kuntu anā ḥajījuhu yawm al-qiyāma. wa man ādhāhum ādhānī wa man ẓalamahum ẓalamanī wa anā akūn khaṣmahu yawm al-ḥisāb wa al-‘iqāb yawm yadkhul qabrahu waḥdahu.

“Whoever shows enmity towards them, then he has shown enmity towards me and towards Allah, may He be exalted. The Lord—exalted be He—and I shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment.”

“man ‘ādāhum ‘adānī wa ‘adā Allāhu subḥānahu wa anā wa al-rab subḥānahu akūn ḥajījahu yawm al-qiyāma.”

“Whoever does them harm does me harm and I shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment, his recompense will be the fire of hell and he will be free of my protection.”

“wa man ādhāhum ādhānī wa anā khaṣmuhu yawm al-qiyāma wa jazā’uhu nāru jahanam wa bari’at minhu dhimmatī.”

3. Early Testimonies Attesting the Authenticity of the Covenants

- In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful

- …

- …

- The protection of Allah and the security of His messenger (dhimmat Allāh wa ḍamān rasūlihi)

- …

- It was witnessed by ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. ‘Awf

- al-Zuhrī and Abū ‘Ubayda b. al-Jarrāḥ.

- Its scribe is Muʿāwiya…

- The year thirty-two.30

“A man among them named Mu‘āwiya took the reins of government of the two empires: Persian and Roman. Justice flourished under his reign, and a great peace was established in the countries that were under his government, and allowed everyone to live as they wished. They [i.e., the Muslims] had received, as I said, from the man who was their guide [i.e., Prophet Muḥammad], an order [i.e., a covenant] in favour of the Christians and the monks… Of each person, they required only tribute [i.e., the jizya] allowing him to remain in whatever faith he wished… While Mu‘āwiya reigned there was such a great peace in the world as was never heard of, according to our fathers and our fathers’ fathers…31 … There was no difference between pagan and Christian, the believer was not distinct from the Jew, and did not differ from the deceiver.”

“He [Muḥammad] said to me: ‘It is my duty to order my people not to take the jizya or kharāj from monks, to respect them and to fulfill their needs and to care for their circumstances. And I will demand from them, with regard to all the Christians, that they do not to act unjustly towards them, and that their ceremonies will not be changed, and that their churches will be built, and that their heads will be raised, and that they will be advanced and treated justly. And whoever is unjust to one of them I shall be his foe on the Day of the Judgment (wa man ẓalama aḥadan minhum kuntu khaṣmahu yawm al-qiyāma).’”

“The Arabs mobilized at Yathrib. Head of them was a man called Muḥammad b. ‘Abdullāh and he became their chief and king… Christians from among the Arabs as well as other people came to him. He granted them protection and wrote for them documents and he did so to all other nations who opposed him. By that I mean the Jews, Magi, Sabaeans and others. They gave him allegiance and took from him a guarantee of safety on the condition that they would pay him the jizya and kharāj.”

“The Christians from among the Arabs and other [nations] came to him, so he granted them protection and wrote documents for them. He did the same with the Jews, the Magi, the Sabaeans as well as others, so they pledged allegiance to him and were granted protection in return for paying the jizya and kharāj64… Christian chronicles report that he was benevolent and compassionate to them so they sent him a delegation requesting his protection. In return he imposed on them the jizya, was gracious to them, and wrote for them documents to guarantee their protection. He informed ‘Umar: ‘Say to them that their livelihoods, wealth and honour is exactly the same as ours’… He also said: ‘Whoever oppresses a protected person he shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment (man ẓalama dhimmiyyan kāna khaṣmahu yawm al-qiyāma),’ and: ‘Whoever harms a protected person has harmed me (man adhā dhimmiyyan fa-qad ādhānī).’”

4. The Curious Silence in Muslim Tradition

“For all canonical or non-canonical traditions, labelled mutawātir or otherwise, to be found in Muslim ḥadīth literature, not a single one has proto-wording supported by isnād strands which, when analytically surveyed together, show the requisite number of authorities—three, four, five or more—in every tier, i.e., on every separate level of transmission, from the very beginning to the very end.

The only criterion that is found to apply to various so-called mutawātir transmissions is that of the requisite number of different transmitters in the oldest tier, i.e., the number of Companions allegedly transmitting one and the same saying from the Prophet or reporting on one and the same event in his life. But in later tiers of the isnād strands within these transmissions this requisite number cannot be established.”

“With pious intention, fabrications were combated with new fabrications, with new ḥadīths which were smuggled in and in which the invention of illegitimate ḥadīths were condemned by strong words uttered by the Prophet… The most widely spread polemical ḥadīth of this nature is the saying which survives in many versions: … ‘Man who lies wilfully in regard to me enters his resting place in the fires of hell.’ About eighty companions—not counting some paraphrases—hand down this saying, which is recognizable as a reaction against the increasing forgery of prophetic sayings.”

“It has been related to us from ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib, ‘Abdullāh b. Mas‘ūd, Mu‘ādh b. Jabal, Abū al-Dardā’, Ibn ‘Umar, Ibn ‘Abbās, Anas b. Mālik, Abū Ḥurayra, Abu Sa‘īd al-Khudrī through many chains of transmission and in various forms that the Messenger of Allah said: ‘Whoever from my umma has memorized 40 traditions relating to their religion will be raised by Allah on the Day of Judgment in the company of jurists and scholars’. In another narration he said: ‘He will be raised as a jurist and scholar’. In the narration on the authority of Abū al-Dardā’ he said: ‘I will be on the Day of Judgment a witness and intercessor for him’. In a narration on the authority of Ibn Mas‘ūd he informs us that: ‘It will be said to him enter paradise from whichever gate you wish’. In the narration of Ibn ‘Umar it is said: ‘He will be classed as a scholar and raised among the martyrs’. According to their classification deriving from their numerous works, the scholars of ḥadīth have agreed that this is a weak tradition even though it has been transmitted by numerous chains of transmission.”

5. Harming a Dhimmī in the Books of Ḥadīth

“It was narrated to me by some of those scholars who came before us (ba‘d al-mashāyikh al-mutaqaddimīn) and who have raised this ḥadīth to the Prophet—peace and blessings be upon him—that when he appointed ‘Abdullāh b. Arqam to take the jizya from the protected people he said to him: ‘Whoever oppresses a person with whom we have made a contract with (man ẓalama mu‘āhidan), or places a burden on him more than he can bear, or takes away any of his rights, or takes something from him unwillingly (bi-ghayr ṭīb nafs), then I shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment (fa anā ḥajījuhu yawm al-qiyāma).”

“Yūsuf b. Yaḥyā narrated to us from Ibn Wahb from Abū Ṣakhr al-Madanī that Ṣafwān b. Sulaym informed him on the authority of 30 children of the Companions of the Messenger of Allah—peace and blessings be upon him—from their fathers, directly from the Messenger of Allah—peace and blessing be upon him—that he said: ‘Whoever oppresses a person with whom we have made a contract with (man ẓalama mu‘āhidan), or places a burden on him more than he can bear, or takes away any of his rights, or takes something from him unwillingly (bi-ghayr ṭīb nafs minhu) then I shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment (fa anā ḥajījuhu yawm al-qiyāma)’. The Messenger of Allah–peace and blessings be upon him–then pointed to his chest with his fingers and said: ‘Whoever kills a person who has made a contract with us and who has the protection of Allah and His messenger (lahu dhimmatu Allāhi wa rasūlihi), Allah has forbidden him the scent of paradise even though its scent can be felt at a distance of 70 years.’”

“Yūsuf b. Yaḥyā narrated to us from Ibn Wahb from al-Ḥajjāj b. Ṣafwān al-Madīnī from Ibrāhīm b. ‘Abdullāh b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān, from his father, that the Messenger of Allah—peace and blessings be upon him—said: ‘Whoever oppresses a person with whom we have made a contract with (man ẓalama mu‘āhidan) I shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment (fa anā ḥajījuhu yawm al-qiyāma); whoever sells a free person and consumes the money he has obtained from such a sale, I shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment (fa anā ḥajījuhu yawm al-qiyāma); and whoever is unjust to a person who is owed a wage I shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment (fa anā ḥajījuhu yawm al-qiyāma)’”.

“Ibrāhīm b. Abī Yaḥyā narrated to us from al-‘Abbās b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān from Zayd b. Rufay‘ that the Messenger of Allah–peace and blessings be upon him–said: ‘Whoever oppresses a person with whom we have made a contract with (man ẓalama mu‘āhidan), or places a burden on him more than he can bear, then I shall be his foe until the Day of Judgment (fa anā ḥajījuhu ilā yawm al-qiyāma)’”.

“Muḥammad b. Ḥumayd narrated to us from ‘Umar b. al-Ḥasan al-Qāḍī al-Ḥalabī from Ayūb al-Wazān from Ya‘lā b. al-Ashdaq from ‘Abdullāh b. Jarād that the Messenger of Allah—peace and blessings be upon him—said: ‘Whoever oppresses a dhimmī (man ẓalama dhimmiyyan) who is paying the jizya and who accepts being humiliated, then I shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment (fa anā khaṣmuhu yawm al-qiyāma)’”.

“Muḥammad b. Sa‘d narrated from al-Wāqidī: Some people in Lebanon rebelled because they were complaining about the collector of the kharāj in Ba‘albek. This made Ṣāliḥ b. ‘Alī b. ‘Abdullāh b. ‘Abbās send troops against them to destroy their fighting power and to allow the rest of the population to retain their [Christian] faith. Ṣāliḥ sent them back to their villages but expelled other natives of Lebanon. Al-Qāsim b. Sallām related to me on the authority of Muḥammad b. Kathīr that Ṣāliḥ received a long communication from al-Awzā‘ī of which the following extract has been preserved: ‘You have heard of the expulsion of the protected people from Mount Lebanon although they did not side with those who rebelled—many of whom you killed and the rest which you allowed to return to their villages. How then can you punish the many for the fault of the few and make them leave their homes and possessions in spite of Allah’s decree that ‘no soul shall bear the burden of another (Q6: 164)’. The most rightful course of action for you is to abide and obey the command of the Prophet with the strictest of observance when he said ‘Whoever oppresses a person with whom we have made a contract with (man ẓalama mu‘āhidan), or places a burden on him more than he can bear, I shall be his foe (fa anā ḥajījuhu).’’”

- Whoever harms a protected person I am his foe (man adhā dhimmiyyan fa anā khaṣmuhu);

- Whoever harms a protected person I am his foe, and whoever I am his foe then I shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment (man adhā dhimmiyyan fa anā khaṣmuhu wa man kuntu khaṣmahu khāṣamtuhu yawm al-qiyāma);

- Whoever harms a protected person I am his foe on the Day of Judgment (man adhā dhimmiyyan fa anā khaṣmuhu yawm al-qiyāma);

- Whoever harms a protected person has harmed me (man adhā dhimmiyyan fa-qad ādhānī);

- Whoever harms a protected person I am his foe (man adhā dhimmiyyan kuntu khaṣmahu);

- Whoever harms a protected person I shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment (man adhā dhimmiyyan kuntu khaṣmahu yawm al-qiyāma);

- Whoever oppresses a protected person Allah shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment or I shall be his foe (man ẓalama dhimmiyyan kān Allāhu khaṣmahu yawm al-qiyāma aw kuntu khaṣmahu);89

- Whoever maligns a protected person I am his foe (man adhmā dhimmiyyan fa anā khaṣmuhu).”90

6. Textual Analysis in the Context of Multiple Transmissions

7. Are the Ḥadīths in Harmony with the Covenants?

7.1. Granting the Protection of Allah and His Messenger

7.2. Taxation

7.3. Building of New Churches

7.4. Levying the Jizya on the Magi

“Yaḥya related to me from Mālik from Ja‘far b. Muḥammad b. ‘Alī, from his father [i.e., most likely a reference to al-Ḥusayn as the source of the narration] that the matter of the Magi was mentioned to ‘Umar b. al-Khaṭṭāb for which he said ‘I do not know how to deal with them’. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. ‘Awf then said, “I bear witness that I heard the Messenger of Allah—peace and blessings be upon him—say ‘Deal with them as you do with the People of the Book.’”

7.5. Expelling the Jews and Christians from the Arabian Peninsula

7.6. Two Creeds Cannot Inherit One Another

8. Compromising the Terms and Conditions of the Original Covenants

“I do not consider it appropriate to annul anything of what was agreed in the treaties nor any attempts to terminate what Abū Bakr, ‘Umar, ‘Uthmān and ‘Alī—may Allah be pleased with them all—agreed with them. Rather their policy should be maintained for they did not rescind on anything which was agreed with them in the treaties that they concluded. As for any new synagogues and churches that are built, then these should be destroyed. This was the opinion of more than one Caliph and those who preceded us.

Some Muslims had sought to destroy the synagogues and churches in the [newly conquered] cities and provinces but the people of those cities took out their treaties in which these agreements were made between them and the Muslims. The jurists and the Successors reprimanded those Muslims who had considered destroying their synagogues and churches until they no longer entertained the idea.

The truce is applicable based on what ‘Umar–may Allah be pleased with him—stipulated with them, that it is applicable until the Day of Judgment.”

“It is my most imperial command that those who have command over the affairs in my realm, be it by land or by sea, shall protect and preserve the Patriarch of Jerusalem and the aforementioned monks from molestation by anyone; should anyone, be he one of my successors, or one of my high ministers, or one of the ulema, or some civil authority, or one of the slaves of my court, or anybody else from the Muslim community, wish, for money or favour, to annul [this command], may he encounter the wrath of God and His revered Prophet!”

9. Incorporating the Covenants into Islamic Law

10. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Cross-Comparison of the Witnesses’ Names in the Christian Covenants

| Gabriel210/Aubert211 Covenant | Graf212/Akyüz213 Covenant | Hill214/Morrow215 Covenant |

| MATCHING NAMES | ||

|

|

|

| MATCHING NAMES WHICH ARE MOST LIKELY THE RESULT OF INCORRECT TRANSCRIPTION | ||

|

|

|

| MATCHING NAMES WITH MORE THAN ONE COVENANT | ||

|

|

|

| NAMES THAT DO NOT MATCH | ||

|

|

|

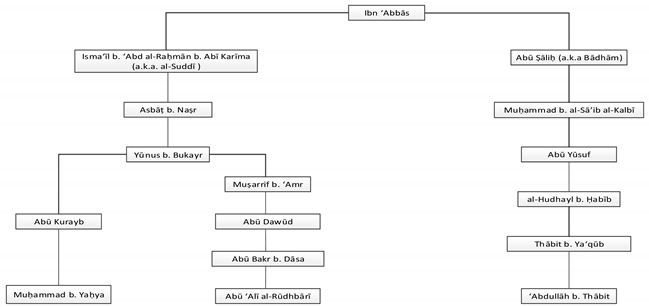

Appendix B. The Isnād Bundles of the Najran Compact

| ||

| Abū ‘Ubayd216 | Ibn Zanjawayh217 | Ibn Shabba218 |

| ||

| Abū al-Shaykh al-Iṣfahānī219 | al-Bayhaqī220 | Muqātil b. Sulaymān221 |

References

- ‘Alī b. al-Ḥasan b. Hibatullāh b. ‘Abdullāh, know as Ibn ‘Asākir. 1995. Tārīkh Madīnat Dimashq. Beirut: Dār al-Fikr, vol. 2, pp. 175–9. [Google Scholar]

- ‘Abd al-Raḥmān Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūtī. 1975. al-Āla’ al-Maṣnū’a fī al-Aḥādīth al-Mawḍū’a. Beirut: Dār al-Ma’rifa, p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Abū ‘Abdullāh Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasanal-Shaybānī. 1975. Kitāb al-Siyar al-Ṣaghīr. Beirut: al-Dār al-Mutaḥida lil-Nashr, p. 267. [Google Scholar]

- Abū ‘Abdullāh Muḥammad b. Yasīl al-Ḥumaydī. 1992. Musnad. ḥadīth No. 85. Damascus: Dār al-Saqā, vol. 1, p. 198. [Google Scholar]

- Abū Bakr Aḥmad b. Mūsā al-Bayhaqī. 2003. Sunan al-Kubrā. ḥadīth No. 18731. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyya, vol. 9, p. 344. [Google Scholar]

- Abū Ja‘far Muḥammad b. Ya‘qūb al-Kulaynī. 2000. al-Kāfī. Tehran: Dār al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyya, vol. 5, p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Aḥmad b. ‘Abdullāh b. Aḥmad al-Mihrānī al-Isfahānī, known as Abū Nu’aym. 1990. Dhikr Akhbār Iṣfahān. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyya, vol. 1, pp. 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Aḥmad b. ‘Abdullāh b. Aḥmad al-Mihrānī al-Isfahānī, known as Abū Nu’aym. 1994. Musnad Abī Ḥanīfa. Riyadh: Maktabat al-Kawthar, p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- Aḥmad b. ‘Abdullāh b. Aḥmad al-Mihrānī al-Isfahānī, known as Abū Nu’aym. 1998. Ma’rifat al-Ṣaḥāba. ḥadīth No. 4059. KSA: Maktabat al-Waṭan, p. 1612. [Google Scholar]

- Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā al-Balādhurī. 1987. Kitāb Futūḥ al-Buldān. Beirut: Mū’assasat al-Ma’ārif, p. 222. [Google Scholar]

- Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā al-Balādhurī. 2011. The Origins of the Islamic State: Being a Translation from the Arabic Accompanied with Annotations, Geographic and Historic Notes of the Kitāb Futūḥ al-Buldān. Translated by Philip Khūri Hitti. New York: Cosimo Classics, pp. 250–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ahroni, Reuben. 1998. Some Yemenite Jewish Attitudes towards Muḥammad’s Prophethood. Hebrew Union College Annual 69: 49–99. [Google Scholar]

- Akyüz, Gabriel. 2002. Osmanlı Devletinde Süryani Kilisesi. Mardin: Kirklar Kilisesi, p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- al-’Ārif, ‘Ārif. 1999. al-Mufaṣsal fī Tārīkh al-Quds. Jerusalem: Maṭba’at al-Ma’ārif, vol. 1, p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- al-’Ayāshī, Muḥammad b. Mas’ūd. 1991. Tafsīr al-’Ayāshī. Beirut: Mu’assasat al-A’lamī lil-Matbū’at, vol. 1, p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- al-Albānī, Muḥammad Naṣr al-Dīn. 1980. Ghāyat al-Marām. Beirut: al-Maktab al-Islāmī, p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Al-ʿĀmilī, al-Ḥurr. 2000. Wasā’il al-Shī’a. Qom: Mū’assasat Al Bayt, vol. 15, p. 153. [Google Scholar]

- al-ʿAsqalānī, Ibn Ḥajar. 1995. al-Takhlīṣ al-Ḥabīr. Cairo: Mū’assasat Qurṭuba, pp. 183–84. [Google Scholar]

- al-Baghdādī, al-Khaṭīb. 1357 AH. al-Kāfiyya fī ‘Ilm al-Riwāya. Hyderabad: Dā’ira al-Ma’ārif al-’Uthmāniyya, p. 430.

- al-Baghdādī, al-Khaṭīb. 2001. Tārīkh Baghdād. Beirut: Dār al-Gharb al-Islāmī, vol. 9, p. 343. [Google Scholar]

- al-Bukharī, Muḥammad b. Ismā‘īl. 2002. Ṣaḥīḥ. Book 58, ḥadīth nos. 3156–7. Beirut: Dār Ibn Kathīr, p. 779. [Google Scholar]

- Abū al-Hasan ′Alī b. ′Umar al-Dāraqutnī. 2001. Sunan. Book 27, hadīth No. 4392. Beirut: Dār al-Ma’rifa, vol. 3, p. 451. [Google Scholar]

- al-Iṣfahānī, Abū al-Shaykh. 1992. Ṭabaqāt al-Muḥadithīn bi-Iṣfahān. Beirut: Mū’assasat al-Risāla, vol. 1, pp. 231–34. [Google Scholar]

- al-Jalabī, Alī Ḥasan. 1999. Mawsū’at al-Aḥādīth wa al-Athār al-Ḍa’īfa wa al-Mawḍū’a. Riyadh: Maktaba al-Ma’ārif lil-Nashr wa al-Tawzī’, vol. 9, pp. 134–35. [Google Scholar]

- al-Jawzī, Ibn al-Qayyim. 1966. Kitāb al-Mawdū’āt. Madīna: Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Ḥasan, vol. 2, p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- al-Ka’bī, Abū al-Qāsim. 2000. Qubūl al-Akhbār wa Ma’rifat al-Rijjāl. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyya, p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- al-Kattānī, Abī ‘Abdullāh b. Muḥammad b. Ja’far. n.d. Nuẓum al-Mutanāthir fī al-Ḥadīth al-Mutawātir. Cairo: Al-Taqadum, pp. 60–63.

- al-Makīn, Jirjis b. al-ʿAmīd. 1625. Historia Saracenica Arabicè & Latinè. Georgius Elmacinus. Translated and Edited by Thomas Erpenius. Lugduni Batavorum: Erpenius, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- al-Nawāwī, Yaḥya Sharaf al-Dīn. 1984. Sharḥ al-Arba’īn al-Nawāwiyya fī al-Aḥādīth al-Ṣaḥīḥa al-Nawāwiyya. Damascus: Dār al-Fatḥ, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- al-Nu‘mān b. Muḥammad b. Manṣūr b. Aḥmad b. Ḥayyūn, known as al-Qāḍī al-Nu’mān. 1963. Da’ā’im al-Islām. Cairo: Dār al-Ma’ārif, vol. 1, p. 380. [Google Scholar]

- al-Tirmidhī, Muḥammad b. ʿĪsā. 1996. Jāmi’. ḥadīth No. 1617. Beirut: Dār al-Gharb al-Islāmī, vol. 3, p. 261. [Google Scholar]

- al-Qāsim b. Sallām, known as Abū ‘Ubayd. 1989. Kitāb al-Amwāl. ḥadīth No. 259. Beirut: Dār al-Shurūq, p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- al-Sāmirī, Abū al-Fatḥ b. Abī al-Ḥasan. 1865. Annales Samaritani: Quos ad Fidem Codicum Manu Scriptorum Berolinensium Bodlejani Parisini Kitāb al-Tārīkh Mimmā Taqaddama ‘An al-abā’. Edited by Eduardus Vilma. Gothae: Friderici Andreae Perthes, p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- al-Ṣan‘anī, ‘Abd al-Razzāq. 1983. Muṣannaf. ḥadīth No. 19253. Beirut: al-Maktab al-Islāmī, vol. 10, p. 325. [Google Scholar]

- al-Ṣan‘anī, ‘Abd al-Razzāq. 1989. Al-Amālī fī Āthār al-Ṣaḥāba. ḥadīth No. 24. Cairo: Maktabat al-Qur’ān, p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- al-Shawkānī. 1995. al-Fawā’id al-Majmū’a fī al-Aḥādīth al-Mawḍū’a. Cairo: Dār al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyya, p. 213. [Google Scholar]

- al-Ṭayālsī, Abū Dāwūd. 1999. Musnad. ḥadīth No. 226. Cairo: Hijr lil-Ṭibā‘a wal-Nashr wal-Tawzī’ wal-I‘lān, vol. 1, p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- al-Zanjānī, Mūsā b. Abdullāh. 1343 AH. Madīnat al-Balāgha. Tehran: Manshūrāt al-Ka’ba, vol. 2, pp. 253–55.

- Ash-Shaybani, Imam Muhammad Ibn Al-Hasan. 2006. The Kitāb al-Āthār of Imam Abū Ḥanīfa. Translated by Abdussamad Clarke. London: Turath Publishing, sct. 281. pp. 506–7. [Google Scholar]

- Atiya, Aziz S. 1952. The Monastery of St. Catherine and the Mount Sinai Expedition. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96: 578–86. [Google Scholar]

- Aubert, Jeanne. 1938. Le Serment du Prophète. Paris: Paul Geuthner, pp. 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Avdall, Johannes. 1870. A Covenant of ‘Alí, fourth Caliph of Baghdád, granting certain Immunities and Privileges to the Armenian nation. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 1: 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Barhebraei, Gregorii. 1877. Chronicon Ecclesiasticum. Edited by Abbeloos Joannes Baptista and Thomas Josephus Lamy. Parisiis: Apud Maisonneuve/Lovanii: Excudebat Car. Peeters, vol. iii, sct. 2. p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Beg, Ferīdūn. 1848–1958. Majmū’at Mansha’at al-Salāṭīn. Istanbul: Takvimhane-yi Âmire, vol. 1, pp. 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bravmann, Meїr. 2012. The State Archives in the Early Islamic Era. In The Articulation of Early Islamic State Structures. Edited by Fred Donner. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 183–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cheikho, Louis. 1909. “‘Uhūd Nabī al-Islām wa al-Khulafa’ al-Rāshidīn lil-Naṣārā," Al-Machriq: Revue Catholique Orientale Mensuelle. Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique, p. 617. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mark R. 1999. What was the Pact of ‘Umar? A Literary-Historical Study. Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 23: 100–57. [Google Scholar]

- Çolak, Hasan. 2013. Relations between the Ottoman Central Administration and the Greek Orthodox Patriarchates of Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria: 16th-18th Centuries. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Dadoyan, Seta B. 2013. The Armenians in the Medieval Islamic World: Armenian Realpolitik in the Medieval Islamic World: Paradigms of Interaction Seventh to Fourteenth Centuries. New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers, vol. 2, pp. 169–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, Yasin. 1993. Sunna, hadīth, and Madinan ‘Amal. Journal of Islamic Studies 4: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, Yasin. 1996. Amal v Hadith in Islamic Law: The Case of Sadl al-Yadayn (Holding One’s Hands by One’s Sides) when doing the Prayer. Islamic Law and Society 3: 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Wakil, Ahmed. 2015. New Light on the Collection and Authenticity of the Qurʾan: The Case for the Existence of a ‘Master Copy’ and how it Relates to the Reading of Ḥafṣ ibn Sulaymān from ʿĀṣim ibn Abī al-Nujūd. Journal of Shi’a Islamic Studies 8: 409–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Wakil, Ahmed. 2016. The Prophet’s Treaty with the Christians of Najrān: An Analytical Study to Determine the Authenticity of the Covenants. Oxford Journal of Islāmic Studies 27: 273–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Wakil, Ahmed. 2017. Searching for the Covenants: Identifying Authentic Documents of the Prophet Based on Scribal Conventions and Textual Analysis. Master’s dissertation, Hamad Bin Khalifa University, Doha, Qatar. [Google Scholar]

- El-Wakil, Ahmed. 2019. The Prophet’s Letter to al-ʿAlāʾ b. Al-Ḥaḍramī: An Assessment of Its Authenticity in Light of the Covenants and the Correspondence with the People of Yemen. Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 30: 231–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Wakil, Ahmed, and Walaa Nasrallah. 2017. The Prophet Muḥammad’s Covenant with the Armenian Christians: A Critical Edition based on the Reconstructed Master Template. In Islām and the People of the Book. Edited by John Andrew Morrow. England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, vol. 2, sct. 54. p. 504. [Google Scholar]

- Fatoohi, Louay. 2013. Abrogation in the Qur’an and Islamic Law: A Critical Study of the Concept of Naskh and Its Impact. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Book Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Fourmilab. n.d. Date Converter. Available online: http://www.fourmilab.ch/documents/calendar (accessed on 15 November 2017).

- Gabriel, Michel. 1900. Tārīkh al-Kanīsa al-Anṭākiyya al-Suryāniyya al-Mārūniyya. Ba’abda: Al-Matba’a al-Libnāniyya, pp. 588–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazarian, Jacob G. 2008. Armenians in Islamicjerusalem. Journal of Islamicjerusalem Studies 9: 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Goitein, Shelomo Dov. 1993. Kitāb Dhimmat an-Nabī. Kiryat Sefer 9: 507–21. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Goldziher, Ignaz. 1971. Muslim Studies. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., vol. 2, p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, Georg. 1914. Ein Schutzbrief Muḥammeds für die Christen, aus dem Münchener Cod. arab. 210b. Mitteilungen der Vorderasiatischen Gesellschaft 22: 181–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hamidullah, Muhammad. 1987. Majmūʿat al-Wathāʾiq al-Siyāsiyya li-l-ʿahd al-Nabawī wa-l-Khilāfat al-Rāshida. Beirut: Dār al-Nafāʾis, p. 563. [Google Scholar]

- Hansu, Hüseyin. 2009. Notes on the Term Mutawātir and its Reception in Hadīth Criticism. Islamic Law and Society 16: 383–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, and Repository: Fondation Georges et Mathilde Salem. 2008. HMML Proj. Num.: GAMS 01004. Available online: https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/501561 (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Hirschfeld, Hartwig. 1903. The Arabic Portion of the Cairo Genizah at Cambridge. The Jewish Quarterly Review 15: 167–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyland, Robert G. 1997. Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Princeton: Darwin Press, p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyland, Robert G. 2011. Theophilus of Edessa’s Chronicle and the Circulation of Historical Knowledge in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Liverpool: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyland, Robert G. 2015. The Earliest Attestation of the Dhimma of God and His Messenger and the Rediscovery of P. Nessana 77 (60s AH/680 CE). In Islamic Cultures, Islamic Contexts. Edited by Behnam Sadeghi, Asad Q. Ahmed, Adam Silverstein and Robert G. Hoyland. Boston: Brill, pp. 52–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ‘Irāqa, Abū al-Ḥasan ‘Alī b. Muḥammad. 1981. Tanzīh al-Sharī’at al-Marfū’a ‘an al-Akhbār al-Shanī’a al-Mawḍū’a. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyya, vol. 2, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, Yaḥyā. 1987. Kitāb al-Kharāj. ḥadīth No. 235. Beirut: Dār al-Shurūq, pp. 109–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Ḥanbal, Aḥmad. 2001. Musnad. ḥadīth No.1657. Beirut: Mū’assasat al-Risāla, vol. 3, p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Maja. 1432 AH. Sunan. ḥadīth No. 2858. Beirut: Dār Iḥyā’ al-Kutub al-’Arabiyya, vol. 2, p. 953.

- Ibn Sa‘d, Abū ‘Abd Allāh Muḥammad. 2001. al-Ṭabaqāt al-Kubrā. Cairo: Maktabat al-Khānijī, p. 249. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Shabba, ‘Umar. 1996. Tārīkh al-Madīna al-Munawwara. ḥadīth No. 950. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyya, vol. 1, pp. 310–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Shahrashūb, Muḥammad b. ‘Alī. 1956. Manāqib Al Abī-Ṭālib [a.k.a Al-Manāqib]. Qom: Mū’assasat al-Nasharāt ‘Alāma, vol. 1, p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Sulaymān, Muqātil. 2003. Tafsīr. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyya, vol. 1, pp. 211–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Taymiyya, Taqī al-Dīn Aḥmad. 2004. Majmu’at Fatāwī; Madīna: Ministry of Islamic Affairs Dawah and Guidance, vol. 28, p. 653.

- Ibn Taymiyya, Taqī al-Dīn Aḥmad. n.d. Majmu’at al-Rasā’il wa al-Masā’il. Edited by Rashīd Riḍā. Cairo: Lajnat al-Turāth al-’Arabī, vol. 1, p. 228.

- Ibn Zabr, ‘Abdullāh b. Aḥmad b. Rabī‘a. 2006. Juz’ fīhi Shurūṭ al-Naṣārā. Beirut: Dār al-Bashā’ir al-Islāmiyya. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Zanjawayh, Ḥamīd b. Mukhlid. 1986. Kitāb al-Amwāl. ḥadīth No. 621. Riyadh: Markaz al-Mālik Fayṣal lil-Abḥāth wa al-Dirāsāt al-Islāmiyya, p. 381. [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy, Sorabjee Jamsetjee. 1851. Tuqviuti-din-i-Mazdiasna, or, A Mehzur, or, Certificate, Given by Huzrut Maḥomed, the Prophet, of the Moosulmans, on Behalf of Mehdī-Furrookh Bin-Shukhsan (Brother of Sulmān-i-Fārsī, Otherwise called Dinyar Dustoor), and Another Mehzur Given by Huzrut Ally to a Parsee Named Behramshaád-bin-Kheradroos, and to the Whole Parsee Nation. Bombay: Jam-i-Jamsheed Press, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Jiwa, Shainool. 2009. Inclusive Governance: A Fatimid Illustration. In A Companion to the Muslim World. Edited by Amyn Sajoo. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, pp. 157–75. [Google Scholar]

- Juynboll, Gualtherus H. A. 1983. Muslim Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Juynboll, Gualtherus H. A. 2001. (Re) Appraisal of some Technical Terms in Ḥadīth Studies. Islamic Law and Society 52: 303–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, Nuh Ha Mim, and Ahmad ibn Naqib al-Misri. 1997. Reliance of the Traveler: A Classic Manual of Islamic Sacred Law, Revised Edition. Translated and Edited by Nuh Ha Mim Keller. Beltsville: Amana Publications, p. 954. [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Rubin, Milka. 2011. Non-Muslims in the Early Islamic Empire: From Surrender to Coexistence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Library of Congress. MS 695. Manuscripts in St. Catherine’s Monastery. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/amedmonastery.00279391500-ms/?sp=12 (accessed on 14 April 2018).

- Library of Congress. MS 696. Manuscripts in St. Catherine’s Monastery. MS 696. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/amedmonastery.00279388963-ms/?sp=6 (accessed on 14 April 2018).

- Library of Congress. n.d. Manuscripts in St. Catherine’s Monastery. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/amedmonastery.00279389013-ms/?sp=21 (accessed on 14 April 2018).

- Mahboub De Mendbidj, known as Agapius of Hierapolis. 1909. Kitab al-’Unvan: Histoire Universelle. Translated and Edited by Alexandre Vasiliev. Part 1. Paris: Patrologia Orientalis, pp. 456–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mālik ibn Ana, known as Mālik. 1985. Muwaṭṭā’. Book 17, ḥadīth No. 43. Beirut: Dār Iḥyā’ al-Turāth al-’Arabī, vol. 2, p. 279. [Google Scholar]

- Mingana, Alphonse. 1908. Source Syriaques. Leipzig: Otto Harrassowitz, vol. 1, p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, John Andrew. 2013. The Covenants of the Prophet Muḥammad with the Christians of the World. Tacoma: Angelico Press & Sophia Perennis. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, John Andrew, ed. 2017. Islām and the People of the Book: Critical Studies on the Covenants of the Prophe. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, vols. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī. 1879. Tārīkh. Leiden: Brill, vol. 2, p. 637. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, William. 1887. The Apology of Al Kindy: Written at the Court of Al Mâmûn (circa AH 215; AD 830), in Defence of Christianity Against Islam: with an Essay on Its Age and Authorship Read Before the Royal Asiatic Society. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, pp. 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Muslim, Muslim b. al-Ḥajjāj b. 2006. Ṣaḥīḥ. ḥadīth No. 2. Riyadh: Dār Tayyiba lil-Nashr wa al-Tawzī’, vol. 2, p. 829. [Google Scholar]

- Nau, François Nicolas. 1915. Un Colloque du Patriarche Jean avec l’Émir des Agaréens et Faits Divers des Années 712 à 716 d’après le MS du British Museum Add. 17193. Journal Asiatique 5: 225–79. [Google Scholar]

- Nini, Yehudah. 1983. Ketav ḥasüt la-Yehüdīm ha-meyüḥas lannavī Muḥammad. In Meḥqarīm be-Aggadah wuv-Fölklör Yehüdī. Edited by Issachar Ben-Ami and Joseph Dan. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, pp. 157–96. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Penkaye, John Bar. 2010. Summary of World History (Rishe Melle). Book 15. Translated by Alphonse Mingana, and Roger Pearse. The Tertullian Project: Early Church Fathers–Additional Texts. Available online: http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/john_bar_penkaye_history_15_trans.htm (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Penn, Michael Philip. 2015. When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Rivlin, Yosef. 1935. Ṣava’at Muḥammad le-’Alī ben Abī Ṭālib. In Minḥa le-Davīd: David Yelin’s Jubilee Volume. Jerusalem: Va’ad ha-Yövel, pp. 139–56. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, Barbara. 2009. The Legend of Sergius Baḥīrā: Eastern Christian Apologetics and Apocalyptic in Response to Islam. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 61–93. [Google Scholar]

- Saʿīd ibn Baṭrīq, known as Eutychius. 1909. Annales. Beirut: E Typographeo Catholica, vol. 7, pp. 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sayyid ‘Alī Khān al-Shīrāzī. 1397 AH. al-Darajāt al-Rafī’a fī Ṭabaqāt al-Shī’a. Qom: Maktaba Baṣīratī, pp. 206–7.

- Schacht, Joseph. 1953. The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Scher, Addai. 1983. Histoire Nestorienne Inédite: Chronique de Séert, Deuxième Partie. Patrologia Orientalis, Tome XIII, Fascicule 4, No. 65. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 601. First published 1918. [Google Scholar]

- Sharon, Moshe. 2018. Witnessed By Three Disciples of the Prophet: The Jerusalem 32 Inscription From 32 AH/652 CE. Israel Exploration Journal 68: 100–11. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Samuel Miklos. 1964. Fāṭimid Decrees: Original Documents from the Fāṭimid Chancery. London: Faber and Faber. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaymān b. al-Ash‘ath al-Azdī, known as Abū Dāwūd. 2009. Sunan. ḥadīth No. 3052. Beirut: Dār al-Risāla al-’Alāmiyya, vol. 4, p. 658. [Google Scholar]

- Szilágy, Krisztina. 2014. The Disputation of the Monk Abraham of Tiberias. In The Orthodox Church in the Arab World (700–1700): An Anthology of Sources. Edited by Samuel Noble and Alexander Treiger. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Szilágyi, Kristina. 2008. Muḥammad and the Monk: The Making of the Christian Baḥīrā Legend. Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 34: 169–214. [Google Scholar]

- Ṭabarsī, Mirzā Ḥusayn al-Nūrī. 1381 AH. Kalima Ṭayyiba. Tehran: Islāmiyya, pp. 60–61.

- Ṭabarsī, Mirzā Ḥusayn al-Nūrī. 1988. Mustadrak al-Wasā’il. Beirut: Mū’assasat Al al-Bayt alyahim al-salām li-Iḥya al-Turāth, vol. 11, p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Tartar, Georges. 1997. Ḥiwār Islāmī-Masīḥī fī ‘ahd al-Khalīfat al-Ma’mūn. Strasbourg: Jāmi’at al-’Ulūm al-Insāniyya, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, Robert W. 1994. Muhammad and the Origin of Islam in Armenian Literary Tradition. In Studies in Armenian Literature and Christianity. Edited by Robert William Thomson. Aldershot: Variorum, pp. 829–58. [Google Scholar]

- Treaty for Quds. 15 AH. Available online: http://www.lastprophet.info/treaty-for-quds (accessed on 16 November 2018).

- Tritton, Arthur Stanley. 1930. The Caliphs and their Non-Muslim Subjects. Humphrey Milford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Philip. 2013. The ‘Chronicle of Seert’: Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ya‘qūb b. Ibrāhīm al-Anṣarī, known as Abū Yūsuf. 1999. Kitāb al-Kharāj. Cairo: al-Maktaba al-Azhariyya, p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- Zayd b. ‘Alī b. al-Ḥusayn b. ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib, known as Zayd b. ‘Alī. 1999. Musnad. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyya, pp. 313–14. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

| 2 | For a contemporary definition rooted in classical Muslim orthodoxy, see (Keller and al-Misri 1997), w48.2. For the definition given by Abū al-Qāsim al-Balkhī, see (Hansu 2009, pp. 391–92). |

| 3 | (Gabriel 1900). |

| 4 | (Aubert 1938). |

| 5 | (Gabriel 1900), Tārīkh al-Kanīsa, p. 588. |

| 6 | (Aubert 1938). For a copy of a covenant addressed to the Christian Jacobites, see Akyüz 2002. |

| 7 | (Gabriel 1900), Tārīkh al-Kanīsa, p. 594. |

| 8 | |

| 9 | (Ar. 202 2008). The Covenant is on pages 155b–162a. The Prophetic warning is on p. 161b. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | (Ar. 202 2008), p. 155b reads “katabahu lil-sayyid” which may be an allusion to al-Sayyid Ghassānī who received a number of covenants from the Prophet and which he distributed to other Christian denominations. As for the Morrow recension which was discovered in Egypt, it reads “katabahu al-Asad” being a reference to ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib (see Morrow, ibid., Covenants, p. 255). For more background information see (El-Wakil 2016). |

| 12 | See (Akyüz 2002), Osmanlı Devletinde Süryani Kilisesi, pp. 158–61. |

| 13 | (Graf 1914), “Ein Schutzbrief Muḥammeds für die Christen,” p. 562. (Akyüz 2002), Osmanlı Devletinde Süryani Kilisesi, p. 159. |

| 14 | (Graf 1914), “Ein Schutzbrief Muḥammeds für die Christen,” p. 565; (Akyüz 2002), Osmanlı Devletinde Süryani Kilisesi, p. 160. |

| 15 | (Cheikho 1909), Uhūd Nabī al-Islām, p. 617. |

| 16 | Cheikho ibid. |

| 17 | Cheikho, ibid. |

| 18 | |

| 19 | (Hamidullah 1987). The Julian date was derived from the (Fourmilab n.d.). |

| 20 | The early dating of the covenants is certainly problematic, but these dates should nevertheless be accepted as genuine despite the lack of historical data to justify them. The Prophet had good relations with the Christians of Najran from the time he was in Makkah, and it appears that the latter played a key role in conveying his covenants to the main mother churches which were represented in South Arabia i.e., Miaphysite, Chalcedonian, and Nestorian. We also have two Christian texts prophesizing Muḥammad’s future by monks who either visited or resided in Mount Sinai. The first is the apocalypse of Sergius Baḥīra who was shown the future of the Arab empire by an angel who visited him on Mount Sinai. See (Roggema 2009). The second is a text reported by Aḥmad Zakī Basha and recorded by Hamidullah in which a monk residing on Mount Sinai and knowledgeable in astrology accurately prophesised the future of the young Muḥammad. See (Hamidullah 1987), Majmūʿat al-Wathāʾiq al-Siyāsiyya, p. 565. Though deemed credulous in our day and age, prophecies, visions, and miracles were taken very seriously in late antiquity’s cultural milieu. |

| 21 | (El-Wakil 2017), “Searching for the Covenants,” sct. 41, pp. 112–13. Also see (Hirschfeld 1903). Hirschfeld’s translation was edited by me. |

| 22 | (Ahroni 1998, pp. 78–79). Ahroni’s translation was edited by me. For a slight variant where the verb “khaṣama” is used, see (Rivlin 1935, p. 152). The expression therein reads “kuntu anā ḥajījahu wa khaṣmahu yawm al-qiyāma.” Also see (Goitein 1993, p. 509). The verbal noun “khaṣmahu” is omitted and the phrase reads instead “wa lā bārak Allāhu lahu li-man ẓalama banī isrā’īl mithqāl dhara wa anā ḥajījuhu yawm al-qiyāma”. Also see (Nini 1983, p. 196). Nini reads the last clause as “fa-innanī khaṣīmahu wā ḥajījahu yawm al-dīn, yawm al-Ākhir.” One criticism of the Covenant with the Children of Israel is that the Imām should be of the progeny Fāṭima, giving us the impression that it was written during Zaydī rule. However, this may have been an explanatory note to the original covenant which was added to it by the Jews of Yemen. It certainly does not affect the overall authenticity of the text. |

| 23 | Ahroni, ibid., pp. 88–89. Ahroni’s translation was edited by me. |

| 24 | (Jejeebhoy 1851). Also see (El-Wakil 2017) “Searching for the Covenants,” sct. 12, p. 127. |

| 25 | (Rivlin 1935), “Ṣava’at Muḥammad le-’Alī ben Abī Ṭālib,” p. 152. |

| 26 | (Ṭabarsī 1988). |

| 27 | |

| 28 | |

| 29 | |

| 30 | Sharon, ibid., p. 101. |

| 31 | (Mingana 1908). I have relied on the English translation of Roger Pearse. See (Penkaye 2010). |

| 32 | (Mingana 1908), ibid., p. 179. English translation by Roger Pearse. |

| 33 | (Penn 2015). |

| 34 | See (Muir 1887). |

| 35 | (Tartar 1997). I was able to locate a copy of the letter of ‘Abdullāh al-Hāshimī and the response of al-Kindī appended to it in a leather binding completed on Sunday 22 Ṣafar 1093/1 March 1682 in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice. See “Dialogus de rebus Fidei Christianum Mohametanum,” Cod. XIV/MSS. Orientali No. 14, ff. 113, Collocazione 109. This manuscript appears to have been unknown to Tartar. |

| 36 | (Tartar 1997), Ḥiwār Islāmī-Masīḥī, p. 11. |

| 37 | To read the reconstructed Master Template, see (El-Wakil and Nasrallah 2017). The exception to this is the Prophet’s Covenant with the Monks of Mount Sinai. This expression is in the singular form in the Morrow Covenant. Also see Gabriel, Tārīkh al-Kanīsa, p. 593. |

| 38 | (Tartar 1997), Ḥiwār Islāmī-Masīḥī, p. 35. For more details see John Andrew (Morrow 2017), “The Provenance of the Prophet’s Covenants,” pp. 185–88. |

| 39 | |

| 40 | |

| 41 | |

| 42 | |

| 43 | (Ibn Shahrashūb 1956), al-Manāqib, vol. 1, p. 111. |

| 44 | |

| 45 | |

| 46 | (Roggema 2009). Also see the Long Arabic Recension for a similar reference to the covenants: pp. 526–27. |

| 47 | Roggema, ibid., pp. 456–57. Roggema’s translation has been edited by author. |

| 48 | Roggema, ibid., p. 240. |

| 49 | |

| 50 | (Roggema 2009) The Legend of Sergius Baḥīrā, p. 34. |

| 51 | (Wood 2013). |

| 52 | (El-Wakil 2016), “The Prophet’s Treaty with the Christians of Najran,” p. 334. |

| 53 | |

| 54 | The scrolls and MS 695 carry that statement almost identically with small occasional differences. See: Scroll 1, online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/amedmonastery.00279389013-ms/?sp=4; Scroll 2, online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/amedmonastery.00279389013-ms/?sp=7; Scroll 3, online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/amedmonastery.00279389013-ms/?sp=11; Scroll 4, online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/amedmonastery.00279389013-ms/?sp=14; Scroll 5, online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/amedmonastery.00279389013-ms/?sp=18; MS 695, https://www.loc.gov/resource/amedmonastery.00279391500-ms/?sp=13 (accessed on 15 November 2017). |

| 55 | |

| 56 | (El-Wakil and Nasrallah 2017), “The Prophet Muḥammad’s Covenant with the Armenian Christians,” pp. 472–76, 487–505. |

| 57 | (al-Iṣfahānī 1992), Ṭabaqāt al-Muḥadithīn bi-Iṣfahān, vol. 1, p. 231; (Abū Nu’aym 1990), Dhikr Akhbār Iṣfahān, vol. 1, p. 79. |

| 58 | |

| 59 | (Hamidullah 1987), Majmūʿat al-Wathāʾiq al-Siyāsiyya, p. 563. Also see MSS 695 and 696 as well as the five scrolls in St. Catherine’s Monastery. |

| 60 | (Ahroni 1998), “Some Yemenite Jewish Attitudes towards Muḥammad’s Prophethood,” pp. 50, 88–89. Also see (Rivlin 1935), “Ṣava’at Muḥammad le-’Alī ben Abī Ṭālib,” p. 155; (Goitein 1993), “Kitāb Dhimmat an-Nabī,” p. 509; (Nini 1983), “Ketav ḥasüt la-Yehüdīm ha-meyüḥas lannavī Muḥammad,” p. 196. |

| 61 | (El-Wakil 2016), “The Prophet’s Treaty with the Christians of Najran,” pp. 331–32. The Covenant with the Christians of the World was written on Monday 29 Rabī’ al-Thānī 4 AH and the Covenant with the Jews of Khaybar and Maqnā would have been on Friday 3 Ramaḍān 9 AH. |

| 62 | See (El-Wakil 2017), “Searching for the Covenants.” |

| 63 | (Hoyland 2011, p. 87). For the Arabic, see (Agapius 1909, pp. 196–97); Hoyland’s translation was edited by author. |

| 64 | |

| 65 | al-Makīn, ibid., p. 11. |

| 66 | (Hirschfeld 1903), “The Arabic Portion of the Cairo Genizah at Cambridge,” p. 172. |

| 67 | |

| 68 | |

| 69 | (al-’Ārif 1999). Also see (Gabriel 1900), Tārīkh al-Kanīsa, pp. 585–87. (Akyüz 2002), Osmanlı Devletinde Süryani Kilisesi, pp. 146–147; Ottoman Archives in Istanbul, The Church Registers (Kamame Kilisesi Defteri), Register No. 8 (A.DVNS.KLS.d; 1171 AH), p. 5. |

| 70 | (Nau 1915, pp. 276–79). For a summary of this covenant from the Life of Gabriel of Qartmin, see (Hoyland 1997). |

| 71 | (Scher [1918] 1983), Histoire Nestorienne Inédite: Chronique de Séert, pp. 300, 620. |

| 72 | |

| 73 | (Hansu 2009), “Notes on the Term Mutawātir and its Reception in Hadīth Criticism,” p. 395. |

| 74 | |

| 75 | (Schacht 1953). |

| 76 | |

| 77 | (Schacht 1953), The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence, p. 165. |

| 78 | Schacht, ibid., pp. 171–172. |

| 79 | |

| 80 | |

| 81 | (El-Wakil and Nasrallah 2017) “The Prophet Muḥammad’s Covenant with the Armenian Christians,” sct. 33, pp. 495–96. |

| 82 | |

| 83 | |

| 84 | |

| 85 | (Ibn Zanjawayh 1986), Kitāb al-Amwāl, p. 381. |

| 86 | |

| 87 | |

| 88 | (Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā al-Balādhurī 1987). My translation s relied on that of Hitti. See (Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā al-Balādhurī 2011). Also see (Ibn Zanjawayh 1986), Kitāb al-Amwāl, ḥadīth No. 689, p. 420. |

| 89 | For these seven variants see Alī Ḥasan al-Jalabī’s work (al-Jalabī 1999). |

| 90 | al-Jalabī, ibid., p. 191. It appears that the origin of this tradition lies with the word “adhā” having been misread as “adhmā”. |

| 91 | |

| 92 | |

| 93 | |

| 94 | al-Suyūtī, ibid., p. 141. |

| 95 | |

| 96 | (Ibn Taymiyya 2004). Also see (Ibn Taymiyya n.d.). |

| 97 | |

| 98 | (al-Jalabī 1999), Mawsū’at al-Aḥādīth wa al-Athār al-Ḍa’īfa wa al-Mawḍū’a, vols. 10, p. 183. |

| 99 | (Ibn Taymiyya 2004), Majmu’at Fatāwī, vol. 18, p. 128. |

| 100 | Throughout this article, the term “Compact” is used to refer to documents emerging from Muslim sources, while the term “Covenant” is employed in reference to documents originating from non-Muslim sources. |

| 101 | (El-Wakil 2017) “Searching for the Covenants,” pp. 40–48. |

| 102 | |

| 103 | |

| 104 | (Ibn Zanjawayh 1986), Kitāb al-Amwāl, ḥadīth No. 418, p. 276. |

| 105 | Ibn Zanjawayh, ibid., ḥadīth No. 419, p. 277. |

| 106 | Ibn Zanjawayh, ibid., ḥadīth No. 733, pp. 451–52. |

| 107 | (Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā al-Balādhurī 1987), Kitāb Futūḥ al-Buldān, p. 85. Also see (Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā al-Balādhurī 2011), The Origins of the Islamic State, p. 98. |

| 108 | al-Balādhurī, ibid., pp. 86–87. Also see (Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā al-Balādhurī 2011), The Origins of the Islamic State, p. 99. |

| 109 | (Abū Yūsuf 1999), Kitāb al-Kharāj, pp. 84–85. |

| 110 | (Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā al-Balādhurī 2011), The Origins of the Islamic State, p. 101. |

| 111 | |

| 112 | |

| 113 | For a discussion of these anachronisms and the case for Mu’āwiya’s early conversion, see (El-Wakil 2016), “The Prophet’s Treaty with the Christians of Najran,” pp. 286–92. |

| 114 | For an in-depth discussion, see (El-Wakil 2019). |

| 115 | (Goldziher 1971), Muslim Studies, vol. 2, p. 54. |

| 116 | (al-Baghdādī 2001), Tārīkh Baghdād, vol. 1, p. 577. |

| 117 | |

| 118 | Ibn ‘Irāqa, ibid., vol. 6, p. 4. |

| 119 | Ibn ‘Irāqa, ibid., vol. 5, p. 4. |

| 120 | Ibn ‘Irāqa, ibid., p. 4. |

| 121 | Ibn ‘Irāqa, ibid., vol. 3, p. 4. |

| 122 | (Szilágy 2014). |

| 123 | See (El-Wakil 2015). |

| 124 | (Schacht 1953), The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence, p. 165. |

| 125 | Schacht, ibid., p. 152. |

| 126 | To find this expression in various covenants, see (El-Wakil 2017), “Searching for the Covenants,” p. 102, sct. 8 for the Covenant with the Banū Zakān; p. 106, sct. 8 for the Covenant with the Jews of Khaybar and Maqnā; 124, sct. 6 for the Covenant with the Magi; p. 131 sct. 4 for the Covenant of ‘Alī with the Magi. Also see (El-Wakil and Nasrallah 2017), “The Prophet Muḥammad’s Covenant with the Armenian Christians,” p. 504, sct. 54, where the concept of the protection of Allah and His messenger can be found. |

| 127 | (Ash-Shaybani 2006). Translation was edited by author. Also see (Abū Nu’aym 1994) and (Abū ‘Abdullāh Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasanal-Shaybānī 1975), Kitāb al-Siyar al-Ṣaghīr, p. 93. |

| 128 | (Muslim 2006). |

| 129 | |

| 130 | |

| 131 | |

| 132 | |

| 133 | See (Hoyland 2015). |

| 134 | (El-Wakil and Nasrallah 2017), “The Prophet Muḥammad’s Covenant with the Armenian Christians,” pp. 473–74. For Arabic, see sct. 32, pp. 33, 495–96. For the tax stipulation of 4 dirhams which was levied on the Samaritans, see Abulfathi (al-Sāmirī 1865). |

| 135 | |

| 136 | (Hamidullah 1987), Majmūʿat al-Wathāʾiq al-Siyāsiyya, pp. 209, 221. The Prophet’s letter to his governors in Yemen is, however, generic, stating that the jizya should be levied on every adult without specifying whether these should be male or female, free people or slaves (p. 201). The recension of the letter to Mu’ādh b. Jabal states that it should be levied on every adult male and female (p. 213), while the second recension merely states on every adult (p. 214). |

| 137 | (Ahroni 1998), “Some Yemenite Jewish Attitudes towards Muḥammad’s Prophethood,” vol. 97, pp. 84–85. |

| 138 | |

| 139 | al-Qāḍī al-Nu‘mān, ibid., pp. 380–81. |

| 140 | |

| 141 | |

| 142 | (El-Wakil and Nasrallah 2017), “The Prophet Muḥammad’s Covenant with the Armenian Christians,” sct. 52, p. 503. |

| 143 | |

| 144 | |

| 145 | (El-Wakil 2017), “Searching for the Covenants,” pp. 74–75. |

| 146 | (Mālik 1985), Muwaṭṭā’, vol. 2, Book 17, ḥadīth No. 46, p. 281. |

| 147 | Ibid., ḥadīth No. 47, p. 281. |

| 148 | Ibid., ḥadīth No. 48, p. 281. |

| 149 | Ibid., ḥadīth No. 45, p. 280. |

| 150 | |

| 151 | (Ibn Zanjawayh 1986), Kitāb al-Amwāl, ḥadīth No. 398, p. 269. |

| 152 | The Arabic word “kanīsa” can mean either a church or a synagogue. For the sake of simplicity, however, it has been translated as “church” throughout this paper. |

| 153 | (al-Qāḍī al-Nu’mān 1963), Da’ā’im al-Islām, vol. 1, p. 381. |

| 154 | (al-Iṣfahānī 1992), Ṭabaqāt al-Muḥadithīn bi-Iṣfahān, vol. 3, ḥadīth No. 355, p. 38. |

| 155 | (Abū Nu’aym 1990), Dhikr Akhbār Iṣfahān, vol. 1, p. 430. |

| 156 | Abū ‘Ubayd, Kitāb al-Amwāl, ḥadīth No. 260, p. 176. |

| 157 | (Ibn Zanjawayh 1986), Kitāb al-Amwāl, ḥadīth No. 399, p. 269. |

| 158 | (Ibn Zabr 2006). For the first version of the Pact of ‘Umar, see pp. 22–23; for the second version, pp. 23–25. Three different versions with a full isnād can be found in Ibn ‘Asākir (1995). |

| 159 | It is significant that Mu’āwiya commanded that the Great Church at Edessa be rebuilt after it collapsed due the fact of an earthquake, most probably having done so based on the covenants of the Prophet which he had once scribed. See (Hoyland 2011, pp. 170–71). |

| 160 | (Abū ‘Ubayd 1989), Kitāb al-Amwāl, ḥadīth No. 262, pp. 176–77. |

| 161 | (Ibn Zanjawayh 1986), Kitāb al-Amwāl, ḥadīth No. 400, pp. 269–70. |

| 162 | (Mālik 1985), Muwaṭṭā’, vol. 2, Book 17, ḥadīth No. 42, p. 278. |

| 163 | (El-Wakil 2017), “Searching for the Covenants,” p. 128, sct. 14. |

| 164 | (al-Ṣan‘anī 1983). Also see vol. 6, pp. 69, 10025. |

| 165 | (El-Wakil 2017), “Searching for the Covenants,” p. 127, sct. 12, 13, 135. |

| 166 | (al-Ṣan‘anī 1983), Muṣannaf, vol. 10, ḥadīth No. 19390, p. 367 and ḥadīth No. 19261, p. 327. Also see vol. 6, ḥadīth No. 9972, p. 49. |

| 167 | |

| 168 | (El-Wakil 2016), “The Prophet’s Treaty with the Christians of Najran,” pp. 320–5. |

| 169 | (Mālik 1985), Muwaṭṭāa’, vol. 2, Book 45, ḥadīth No. 18, p. 892. |

| 170 | (al-Ṣan‘anī 1983), Muṣannaf, vol. 10 ḥadīth No. 19359, p. 357. |

| 171 | (Mālik 1985), Muwaṭṭā’, vol. 2, Book 45, ḥadīth No. 17, p. 892. |

| 172 | (al-Ṭayālsī 1999). Also see (Abū ‘Abdullāh Muḥammad b. Yasīl al-Ḥumaydī 1992). |

| 173 | (Ibn Ḥanbal 2001), Musnad, vol. 3, ḥadīth No.1691, p. 221; ḥadīth No. 1694, p. 223. |

| 174 | Ibn Ḥanbal, ibid., ḥadīth No. 1699, p. 227. |

| 175 | (Abū Yūsuf 1999), Kitāb al-Kharāj, p. 73. |

| 176 | (Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī 1879), Tārīkh, vol. 2, p. 535. |

| 177 | (al-Ṣan‘anī 1983), Muṣannaf, vol. 10, ḥadīth No. 19365, p. 359; and vol. 6, ḥadīth No. 9985, p. 54. Also see (Ibn Ḥanbal 2001), Musnad, vol. 1, ḥadīth No. 201, p. 329; ḥadīth No. 219, p. 343; (Muslim 2006), Ṣaḥīḥ, vol. 2, ḥadīth No. 63, p. 846; (al-Tirmidhī 1996), Jāmi’, vol. 3, ḥadīth No. 1607, p. 253. |

| 178 | (al-Ṣan‘anī 1989). Also see (al-Ṣan‘anī 1983) Muṣannaf, vol. 6, ḥadīth No. 9992, p. 57; (al-Bukharī 2002), Ṣaḥīḥ, Book 64, ḥadīth No. 4431, p. 1087; Book 56, ḥadīth No. 3035, p. 702; and Book 58, ḥadīth No. 3168, p. 782; (Muslim 2006), Ṣaḥīḥ, Book 25, ḥadīth No. 20, p. 772; and (Abū Dāwūd 2009), Sunan, vol. 4, Book 14, ḥadīth No. 3029, p. 640. |

| 179 | Zayd b. ‘Alī 1999, Musnad, 332. |

| 180 | (El-Wakil 2017), “Searching for the Covenants,” p. 133, sct. 8, 9. |

| 181 | For a good discussion of this ḥadīth, see (al-ʿAsqalānī 1995). |

| 182 | (Abū Yūsuf 1999), Kitāb al-Kharāj, p. 152. |

| 183 | Abū Yūsuf, ibid., p. 160. |

| 184 | Abū Yūsuf, ibid., p. 152. |

| 185 | To read the Treaty with the People of Damascus and how it was a model for all subsequent treaties see (Eutychius 1909). Similar versions of the Treaty have been documented by Ibn ‘Asākir. See Ibn ‘Asākir, Tārīkh Madīnat Dimashq, vol. 2, pp. 117–18; pp. 180–81; pp. 354–55; vols. 6, 59; p. 225. |

| 186 | (Abū Yūsuf 1999), Kitāb al-Kharāj, pp. 160–161. |

| 187 | |

| 188 | |

| 189 | |

| 190 | |

| 191 | (Dadoyan 2013). For a brief discussion see (Ghazarian 2008, pp. 66–68). Ghazarian produced images of the covenants of the Prophet, ‘Alī, and Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn. |

| 192 | (Ghazarian 2008), “Armenians in Islamicjerusalem,” p. 69. |

| 193 | Quoting from (Çolak 2013). |

| 194 | For a brief overview of the history of the Monastery of St. Catherine, including the Prophetic covenant, see (Atiya 1952). |

| 195 | (Çolak 2013), “Relations between the Ottoman Central Administration and the Greek Orthodox Patriarchates,” pp. 53–54. |

| 196 | The General Directorate of State Archives of the Prime Ministry of the Republic of Turkey (now renamed Republic of Turkey Presidency of State Archives) no longer has the exhibition on display; however, the image and text of the document can be consulted at Lastprophet.info, (Treaty for Quds 15 AH) The Jerusalem Covenant was extracted from the Ottoman Archives in Istanbul, The Church Registers, No. 8, p. 5. |

| 197 | See (Akyüz 2002), Osmanlı Devletinde Süryani Kilisesi. |

| 198 | For example, one famous tradition states: “Do not write anything from me, for whoever of you writes anything from me other than the Qur’ān let him erase it. Narrate traditions from me instead for there is no harm in that, but whoever lies about me—the narrator Hammām added the word ‘intentionally’—then he will find his place in the fire of hell.” See (Muslim 2006), Ṣaḥīḥ, Book 53, ḥadīth No. 72, p. 1366. |

| 199 | |

| 200 | (Dutton 1993). |

| 201 | For an excellent discussion of the theory of abrogation, see (Fatoohi 2013). |

| 202 | (al-Dāraqutnī 2001). Al-Dāraqutnī mentions an alternative isnād for this tradition that reads ‘Āsim b. Abī al-Nujūd > Zayd b. ‘Alī > ‘Alī b. al-Ḥusayn. The hadīth is not raised to the Prophet, though its isnād is one of the most reliable. There is reason to deny this tradition, for the Prophet’s Household always advised their followers to weigh a hadīth’s veracity in relation to the Qur’ān. |

| 203 | (al-’Ayāshī 1991). Al-’Ayāshī reports similar traditions on the authority of ‘Alī, al-Ḥusayn, Muḥammad al-Bāqir, and Ja’far al-Ṣādiq, see pp. 19–20. |

| 204 | al-’Ayāshī, ibid., p. 20. |

| 205 | al-’Ayāshī, ibid. |

| 206 | |

| 207 | Examples of this are too numerous to cite, though we may here draw the reader’s attention to the mutawātir tradition permitting a Muslim to wipe his leather socks during ablution and which has been reported by 66 authorities, see (al-Kattānī n.d.). Despite its mutawātir status, this practice was rejected by the Ḥanafīs, the Zaydīs, the Ja’farīs, and the Ismā’īlīs. The same applies for the case of sadl al-yadayn, which was adopted by the Mālikis based on the practice of the people of Madīna, and by the Zaydīs, the Ja’farīs, and the Ismā’īlīs because of traditions they traced back to the ahl al-bayt which they considered more authoritative than the mutawātir traditions going back to the Prophet supporting that the hands be held together in prayer. For a good discussion see (Dutton 1996). |

| 208 | |

| 209 | Hansu explains how, by the time of al-Kattānī, the definition of mutawātir itself changed and that, previously, this tradition was classified by al-Tirmidhī as ṣaḥīḥ ḥasan gharīb. See (Hansu 2009), “Notes on the Term Mutawātir and its Reception in Hadīth Criticism,” p. 404. |

| 210 | (Aubert 1938), Le Serment du Prophète, pp. 40–41. |

| 211 | (Gabriel 1900), Tārīkh al-Kanīsa, pp. 593–94. |

| 212 | (Graf 1914), “Ein Schutzbrief Muḥammeds für die Christen,” p. 566. Names have been deciphered from high-resolution images of the original manuscript, not Graf’s transcriptions. |

| 213 | (Akyüz 2002), Osmanlı Devletinde Süryani Kilisesi, pp. 160–61. |

| 214 | |

| 215 | (Morrow 2013), Covenants, pp. 262–63. |

| 216 | (Abū ‘Ubayd 1989), Kitāb al-Amwāl, ḥadīth No. 504, pp. 280–81. |

| 217 | (Ibn Zanjawayh 1986), Kitāb al-Amwāl, ḥadīth No. 732, pp. 449–50. |

| 218 | |

| 219 | (al-Iṣfahānī 1992), Ṭabaqāt al-Muḥadithīn bi-Iṣfahān, vol. 1, p. 334. |

| 220 | al-Bayhaqī, Sunan, vol. 9, ḥadīth No. 18715, p. 339. |

| 221 | (Ibn Sulaymān 2003). It should here be noted that Muqātil b. Sulaymān was of the generation that preceded al-Kalbī. It, therefore, seems that the transmission of the Najran Compact is an addition to his original work by ‘Abd al-Khāliq b. al-Ḥasan. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El-Wakil, A. “Whoever Harms a Dhimmī I Shall Be His Foe on the Day of Judgment”: An Investigation into an Authentic Prophetic Tradition and Its Origins from the Covenants. Religions 2019, 10, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10090516

El-Wakil A. “Whoever Harms a Dhimmī I Shall Be His Foe on the Day of Judgment”: An Investigation into an Authentic Prophetic Tradition and Its Origins from the Covenants. Religions. 2019; 10(9):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10090516

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl-Wakil, Ahmed. 2019. "“Whoever Harms a Dhimmī I Shall Be His Foe on the Day of Judgment”: An Investigation into an Authentic Prophetic Tradition and Its Origins from the Covenants" Religions 10, no. 9: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10090516

APA StyleEl-Wakil, A. (2019). “Whoever Harms a Dhimmī I Shall Be His Foe on the Day of Judgment”: An Investigation into an Authentic Prophetic Tradition and Its Origins from the Covenants. Religions, 10(9), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10090516