Abstract

The present study describes the function of small-scale maiolica sanctuaries and chapels created in Italy in the sixteenth century. The so-called eremi encouraged a multisensory engagement of the faithful with complex structures that included receptacles for holy water, openings for the burning of incense, and moveable parts. They depicted a saint contemplating a crucifix or a book in a landscape and, as such, they provided a model for everyday pious life. Although they were less lifelike than the full-size recreations of holy sites, such as the Sacro Monte in Varallo, they had the significant advantage of allowing more spontaneous handling. The reduced scale made the objects portable and stimulated a more immediate pious experience. It seems likely that they formed part of an intimate and private setting. The focused attention given here to works by mostly anonymous artists reveals new categories of analysis, such as their religious efficacy. This allows discussion of these neglected artworks from a more positive perspective, in which their spiritual significance, technical accomplishment and functionality come to the fore.

Keywords:

Italian Renaissance; devotion; home; La Verna; sanctuaries; maiolica; sculptures; multisensory experience 1. Introduction

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, ideas about religious sculpture still followed two conflicting trains of thought. On the one hand, writers understood the efficacy of both sculptural and painted images at impressing the divine image onto the mind and soul of the beholder. On the other hand, especially in the context of the home, writers expressed justifiable concern about unorthodox, physical interactions with three-dimensional images (Sarnecka 2018b, p. 274; Galandra Cooper 2019). The present study focuses on the function of small-scale maiolica models of sanctuaries and chapels, a group of devotional objects that has never been studied before in relation to their specific form and medium. Created for a domestic space, to be handled and remind their beholders of the need for a pious life, these are among the most interesting devotional maiolica objects from the point of view of their function. They suggest ways in which artistic ingenuity satisfied the devotional needs of the faithful.

The devotional sculptures recorded in Renaissance inventories are rarely identified by their makers and it seems that subject matter and material were much more important aspects for fifteenth- and sixteenth-century beholders than for audiences today.1 Of primary concern for original viewers was the devotional significance of the represented scene and the role of the object in everyday life, rather than its specific attributions. In the selection of themes, small-scale maiolica sculpture in part reflected the iconographies of large-scale glazed terracotta altarpieces. The iconography of small-scale figures has sometimes been discussed in relation to free-standing terracotta groups painted in cold polychromy from the Po Valley region, created by such celebrated Renaissance artists as Niccolò dell’Arca (c. 1435–1494) or Guido Mazzoni (c. 1445–1518), set in purpose-made niches in various churches (Ravanelli Guidotti 1998, p. 221; Palvarini Gobio Casali 2000; Reale et al. 2008; Bonsanti and Piccinini 2009). The Nativity and the Passion scenes, which were the most popular narratives represented in these life-size terracotta groups, were also illustrated in small-scale glazed terracotta sculptures (Paolinelli 2014; Sarnecka 2018a). The relationship between large- and small-scale sculptures went beyond their common iconographies; scholars have observed the importance of mimesis for both artistic products and the common attention given to the facial expressions (Ravanelli Guidotti 1998, p. 221). The highly individual features of Guido Mazzoni’s life-size sculptures moved the souls of beholders towards a more intense reliving of the sacred events (Lugli 1990, p. 32). We find the same attention given to individual characterizations of figures and settings in small maiolica figures. Unlike large-scale glazed terracotta altarpieces located on high altars or in side-chapels, which functioned primarily as a focal point of devotion during the liturgy, small-scale devotional statuettes fulfilled a variety of different roles. The decoration of everyday objects, such as inkstands, was just one of them (Piccini 2002; Marini 2007; Sarnecka 2018a).

Small, colourful glazed terracotta models of chapels welcomed more direct, physical, and intimate interactions, thus better serving the needs of family worship than large-scale altarpieces in the same medium created by artists from the specialized workshops of the Della Robbia and the Buglioni. Yet, devotional sculptural maiolica is often omitted not only from discussions of glazed terracotta sculpture, but also from studies of Italian Renaissance maiolica, which has privileged investigation of the so-called piatti istoriati—maiolica plates most frequently decorated with classical and mythological scenes. Only recently have scholars taken up sculptural maiolica (Ravanelli Guidotti 1998; Thornton and Wilson 2009; Warren 2014, 2016; Wilson 2016, 2017) and explored its role in Italian devotional practices (Paolinelli 2014; Sarnecka 2018a, 2018b). The attention given here to maiolica models of chapels and sanctuaries reveals new categories of analysis, such as their special religious efficacy, innovative artistic solutions informing devotional experiences and the agency of domestic sculpture. These maiolica objects solicited specific actions through their form, material, iconography and sometimes accompanying texts.

2. Discussion of the Type

During the sixteenth century the Italian city of Urbino became a centre for the production of small-scale maiolica sculptures. The Fontana workshop, active in the city from the mid-1550s (Wilson and Sani 2007, vol. 1, p. 201), gave new impetus to the development of sculptural ceramics (Watson 1986, p. 20). Towards the end of the century, the Patanazzi family, documented in Urbino from around 1575 until 1618 and related to the Fontana workshop, became involved in three-dimensional maiolica (Gardelli 1991, p. 131; Wilson 1996, p. 370; Negroni 1998). To these families, we owe the development of the small maiolica objects that show a chapel, set in a suggestive landscape, with a saintly figure kneeling in prayer or standing, whilst reading a devotional book (Table 1). These forms originated towards the mid-sixteenth century and became increasingly popular by 1600.

Table 1.

The surviving examples of eremi known to the author, attributed to the Patanazzi Workshop.

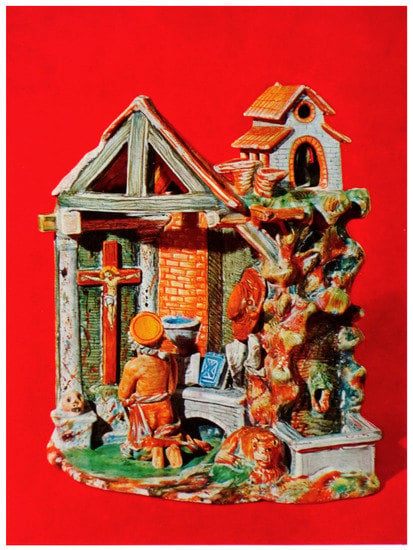

These objects, described by contemporary sources as tempietti or eremi, seem to have played a significant role in shaping the domestic devotional experience (Figure 1). An inventory of the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino indicates a great number of similar objects and confirms that they were used in private residences (Sangiorgi 1976). The document, compiled in 1609, was the first such list created for the duke; the objects listed might have been in the palace for a long time before the beginning of the seventeenth century. The maiolica eremi described in the inventory include a representation of Christ praying in a garden accompanied by an angel, St Jerome in a grotto with the Crucified Christ and two angels above, St Jerome with one angel above, St Mary Magdalene praying before a crucifix below a church atop the grotto, St Mary Magdalene in her cell with four angels and the Crucifix (Figure 2), St Francis in prayer, and a mountain formed of three sections that included the Virgin, St Francis of Paula and St Francis of Assisi (Sangiorgi 1976, pp. 188–89).

Figure 1.

Urbino, Model Altar, c. 1575–1600, maiolica, h: 36 cm, w: 38.5 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, inv. no. C. 258–1926. Photograph © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Figure 2.

Urbino, Eremo with St Mary Magdalene, c. 1580, maiolica, h: 47 cm, w: 37 cm, unknown location, photo from a sales catalogue Finarte, Milan, November 1964.

These objects helped to shape the devotional experiences of people who interacted with them. By viewing saintly figures such as St Jerome, St Francis or St Mary Magdalene in prayer, contemplating the Crucified Christ or reading a devotional book, the faithful who owned these objects were inspired to follow their example. At home, people used a range of different objects to enact their daily prayers. The maiolica eremi may have been employed in private devotions alongside an actual prayer book or a rosary—items depicted in the hands of the saintly figures.

Research conducted on the Renaissance practices of prayer demonstrates that people engaged with the supernatural through sensory experience, which not only involved looking at images but also touching and talking to them (Niccoli 2001, pp. 273–99; Brundin et al. 2018, pp. 179–80, 214–15). This physical interaction was not limited to children’s prayers (Niccoli 2014, pp. 419–20). In fact, the types of figures included in the maiolica models of chapels suggest that they were more suitable for adults than for children. In his first regulation in the Regola del governo di cura familiare of 1419, the Dominican preacher, Cardinal Giovanni Dominici, recommended that parents instruct their children by showing them images of a Young Christ or John the Baptist or the two of them interacting (Dominici 1860, p. 130). What Dominici had to say about the subject matter and the function of paintings in domestic space also applied to statues: ‘e come dico di pinture, così dico di scolture’ (Dominici 1860, p. 131). Such comments imply a very specific kind of interaction with religious images at home, one that gives priority to the iconography and type of representation over the issue of media. Later, in the sixteenth century, Gabriele Paleotti’s guidelines stressed that all religious works of art have the same origins, as all artistic creation begins with a disegno, be it a flat image or one in relief (Paleotti 2002, p. 16).

Indeed, late Medieval and Renaissance polychromed terracotta sculptures point to the close workshop ties between sculptors and painters. Scholars highlight the dilemma in describing devotional reliefs by Antonio Rossellino (1427–1479), a celebrated Florentine artist, as a ‘painted sculpture’ or ‘painting in relief’ (Gentilini 2008, p. 35; Gentilini 2012). This difficulty with the categorization of religious images was not confined to Tuscany. It was a common trend in Renaissance sculpture, linked to the increasing popularity of the medium of polychromed terracotta, which partook of both painterly and sculptural practice. In the case of glazed terracotta, its reflective surface both attracted the eye and had the potential to distract the focused gaze away from the subject matter, so that the faithful could approach the divine not only visually but also through the sense of touch, and subsequently with their minds and souls.

The interchangeability of sculpted and painted images that both Dominici and Paleotti had identified is attested in the written accounts, which shed light on the encounters with domestic devotional images. The inventories of Renaissance households, stories of domestic miracles, and inquisitional records, typically use ambiguous terms, such as ‘cona’ or ‘figura’ (Henry 2011). Unless a document specifies the material from which an object was made, it is impossible to determine its character. Brief terms, such as ‘Item una madonna piccola’ or ‘Item doe madonne et uno presepio con proprio panisello’ (Sarnecka 2018a, p. 170), do not allow us to make clear distinctions between a flat image, a relief and a free-standing figure. Furthermore, inventories prove that devotion at home was also practised in front of multimedia structures. Examining notarial records from Rimini, Angelo Turchini transcribed an inventory which recalled, in the camera da letto of one Francesco Bruni, aromatarius, ‘una tavola depincta et dorata in la quale è depincta la figura de la gloriosa vergine Maria cum el suo dulcissimo figliolo messer Ihesu in gremio [sic, possibly mistranscribed ‘grembo’] con la historia de li Magi che lo adorano, antiqua [...] un crucifisso de petra terracocta depincto sopra dicta tavola (Turchini 1980, p. 356) [A painted and gilded panel with the Virgin Mary in glory with her sweet son, Lord Jesus on her lap with the scene of the adoration of the Magi, ancient [...] a terracotta crucifix polychromed displayed above this panel]. Thus, it seems that the interaction of the painted and sculpted elements of a tabernacle, or in three-dimensional objects such as the maiolica eremi, underwrote domestic experiences of the divine.

3. Scale, Original Collocation and Early Provenance of Maiolica Models of Chapels

In a public space, glazed terracotta groups were typically life or nearly life-size. The figures acted as substitutes for real bodies and facilitated the identification of the viewer with the saintly figures. At home, the scale was obviously reduced for practical reasons. The domestic objects typically measured between 35 and 45 cm in height and width and about 20–30 cm in depth. The smaller scale ensured the intimate nature of the encounter within a household. That intimacy was encouraged by the vividness of the maiolica, accomplished through its surface qualities, life-like colouring, and reflectiveness, all of which animated the object.

The maiolica eremi from the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino were catalogued in a section of the inventory entitled Lista delli vasi di maiolica. The title seems to suggest that they were displayed permanently in the palazzo, together with maiolica decorative vases, perhaps in the credenze. However, it is also likely that the inventory catalogued all objects executed in the same technique regardless of their actual location at the time the inventory was drafted. As devotional objects, they could have been displayed permanently in domestic tabernacles or stored in chests to be taken out temporarily. During domestic prayers they could have been placed on a table covered by a tablecloth, with decoration inspired by church altar cloths. The maiolica image of a saintly figure praying before a crucifix, with beeswax candles lit in front of it, would have transformed ordinary furniture into an altarpiece. The centre of devotion in the Italian Renaissance home was typically the camera da letto, or a bedchamber (Brundin et al. 2018, pp. 66–69). However, the meditative quality of these objects suggests that in elite residences, with more rooms, they might have been displayed on a table in a studiolo for meditation and solitary prayer.

Existing studies of Renaissance interiors focus predominantly on Florence and Venice. Indeed, the visual evidence of the scale of buildings in those cities, such as the Palazzo Davanzati, suggests that in similar interiors a sculpture of 70 or 80 cm in height could have been easily displayed permanently in a tabernacle located in a bedchamber. If we compare the largest maiolica model of a chapel known to the author, namely St Jerome Adoring the Crucifix (from the Musée de la Renaissance, Écouen), which is 54.7 cm in height and 41 cm in width, with some of Antonio Rossellino’s devotional relief stuccos (Horne Museum, stucco, h: 72 cm, w: 52 cm, Bargello, stucco h: 76 cm, w: 51 cm, Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André, stucco h: 79 cm, w: 51 cm, Opava, Slezské zemské muzeum, stucco h: 67 cm, w: 46 cm), which we know were destined for private Florentine homes, the maiolica model is significantly smaller. Moreover, Gentilini categorised Rossellino’s Virgin and Child relief of over 50 cm in height explicitly as the ‘tipo piccolo’ (Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André, h: 53.3 cm, w: 37 cm) (Gentilini 2008, p. 39). Therefore, to follow the Florentine logic, maiolica chapels of approximately 35–45 cm in height would fit perfectly into the purpose-built tabernacles in bedchambers of even less grand structures than the urban palazzi.

The nineteenth-century provenances are often cited as an argument for the church as the original location of many maiolica devotional sculptures. Church provenances, however, should not be surprising, as many devotional objects were sold publicly when a financial need occurred, or were bequeathed to the church or to confraternities after the death of the last family member (Matchette 2006, p. 712). That domestic objects could be inherited by the Church is clear from documentary evidence. Many wills stipulated that a house, with all its moveable and immoveable contents, should be given to a certain church or a monastery after the death of the last family member, or if the family became impoverished and wished to sell the house. Such was the case in Guido Mazzoni’s will (9 July 1518), which stipulated that the members of his family were prohibited from selling the house (proibisce che la casa in alcun tempo possa essere venduta) and, if they attempted the sale, then the rights to the house should be given to the monastery of Saint Peter in Modena (e se la alienavano, i Mazzoni dovevano essere privati di tale diritto e dovevano essere sostituiti nel possesso della casa dal monastero di San Pietro della città di Modena) (Venturi 1889, pp. 155–57). Similar bequests under conditions of entail were not unusual in Renaissance Italy, and the presence of small glazed terracotta sculptures inside churches may be linked to this practice, rather than commissions by the church (Cohn 2011, pp. 8–9).2 The issues of the original collocation and the early provenance of maiolica models of chapels and sanctuaries are challenging and general conclusions should be drawn with caution.

4. Function of Maiolica Models of Chapels and Sanctuaries

The practice of owning small domestic models of chapels and sanctuaries probably developed from the communal need for devotional architectural street shrines, typically referred to as ‘eremo’ or ‘eremitorio’ (Guidotti 1976, p. 15ff; Pia Mannini 1981, p. 11). In fact, some surviving domestic examples are explicitly described as models of wayside shrines. These maiolica forms always feature at least a suggestion of a landscape. The grotto-like structure of the chapels refers to a spiritual refuge. They brought an inspiring aura of religious contemplation and piety into an elite private space, which was very unlike the rustic, derelict chapel depicted in the object (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Urbino, Tempietto with the Praying Virgin (the figurine not originally belonging to the object), c. 1560, maiolica, h: 42.5 cm, w: 45 cm, d: 28 cm, Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche, Faenza, inv. no. 10405,1. Photograph © Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza.

The maiolica hermitages may be seen as domestic extensions of the secluded romite, in which Franciscan friars prayed away from the cities. St Francis stressed the significance of nature in enacting private devotion, a reminder that became increasingly important towards the end of the sixteenth century. This may be linked to Post-Tridentine piety, which highlighted the importance of the contemplation of God in nature. Federico Borromeo (1564–1631) viewed landscape paintings as important vehicles for sending a message about Christian values and commissioned works from artists such as Jan Brueghel the Elder that showed hermits studying sacred texts in the vast landscapes, often with ruins (Jones 1988). A set of engraving—Solitudo, sive Vitae Patrum Eremicolarum—by two Netherlandish artists, Johann and Raphael Sadeler, owned by Borromeo, inspired these paintings (Jones 1988, p. 263) (Figure 4). The genre included important fifteenth-century examples, such as Paolo Uccello’s The Thebaid c. 1460 (Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence), which included St Francis, St Jerome and other saint hermits portrayed in secluded spaces within a vast landscape.

Figure 4.

Johann and Raphael Sadeler, St Onofrius, from the series Solitudo, sive Vitae Patrum Eremicolarum, 1585–86, engraving, h: 17.4 cm, w: 21.3 cm. Metropolitan Museum, New York, inv. no. 49.95.1293(28). Image in the Public Domain.

The maiolica eremi share with these images a similar approach, depicting a figure who contemplates a crucifix or reads a religious book, as in the example from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (Figure 1). In this maiolica chapel, set in nature, St Francis reads piously, and the pilgrim staff placed on the ground before him clearly divides his space from the outside world. Even the angel depicted to the right of the chapel is strikingly aware of her physical presence; she seems to hide behind the chapel’s wall to avoid disturbing the saint. To assist the faithful in imagining themselves sharing the saints’ space and devotional experience, the maiolica models of chapels include telling details, such as the bell by the standing figure of St Francis with a book (Figure 1) or a highly detailed representation of an altarpiece with the crucifix, blue and white altar cloth and two candlesticks (Figure 3). We do find bells in domestic inventories; perhaps they summoned family for prayer (Morse 2007, pp. 170–74). Thus, the maiolica prompted an imagined sound that could have been re-enacted at home with small brass bells.

Another way of merging the space of the faithful with that represented in the model of the chapel was through the use of light. The effects of candlelight upon reflective glazed surfaces would have been particularly transformative (Kupiec 2019, pp. 83–97). Furthermore, candlelight was indispensable if the viewer was to see the deeply recessed details of the statuettes. The Crucified Christ, the Virgin and St John, in the example from the Victoria and Albert Museum, are somewhat concealed within the structure; candlelight would have brought out their forms. The prominent perforations in the roof beams directly above the group would have enhanced this effect, allowing the light to be refracted, thus further animating the scene.

Most of the surviving maiolica sculptures of this type show similarly tranquil, manifestly secluded environments, where the derelict architecture is integrated with nature. The example preserved in the Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza (Figure 5) shows the chapel framed by other religious buildings in a unifying landscape.

Figure 5.

Side view of Figure 3.

The desire to touch and manually operate the figures was an important way in which the beholders interacted with the devotional sculpture in the sixteenth century, and is crucial for understanding of the popularity of the maiolica models of sanctuaries and chapels. The material properties of glazed terracotta—namely the brilliant, vivid colours, durability and portability—called out for physical contact. Moreover, the fired surface, which ensured the immutability of the colours, also reduced the risk of abrasions, even with regular and intense handling. Strength was a unique property of these religious artefacts, as at that time every other painted surface was prone to rubbing off or smudging, due to exposure to natural oils on hands or saliva on lips (Rudy 2010, 2017). Through the centuries, the integrity of small maiolica statuettes was threatened solely by fire and bombardment, as is clear from the present state of the example preserved in Faenza (Mazzotti 2018, p. 37, Figures 15–16 show the state of the eremo before and after the bombardment of 1944).

The Faenza maiolica eremo includes an opening with painted water on the left-hand side. It appears to imitate a lavabo for handwashing before mass, but it seems that there is no system for actual water to flow through this tempietto. However, it is likely that the space served as a receptacle for holy water, as in the many maiolica acquasantiere. Water is important element in all these models, as it facilitated the experience of the imagined space as spiritually real. This feature became a tangible link between the space in which saintly figures were visualized and the space of the faithful. All surviving examples of maiolica eremi have smaller or larger containers, presumably for holy water (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Urbino, Chapel with St Jerome, c. 1590, maiolica, h: 36 cm, w: 35 cm, d: 22 cm, unknown location, photo from a sales catalogue Finarte, Milan, November 1963.

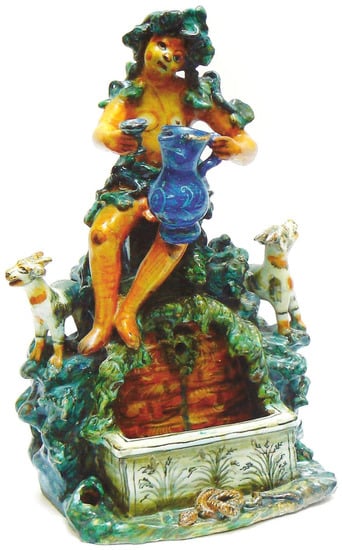

The presence of these openings has led scholars to suggest that similar structures were table fountains, that entertained guests through sprinkling wine during dinner (Gardelli 1987, cat. no. 64 B, p. 150). Such might be true of models with secular themes, such as the Bacchus sitting on a grassy mount, flanked by two goats, pouring wine from a jug to his chalice (Figure 7). However, the prominent religious character of the eremi excludes the entertaining function. The openings, clearly designed to contain a liquid, motivated the shift in the objects’ role. An eighteenth-century inventory of the guardaroba of the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino (1758) confirms that devotional structures with similar openings were used in subsequent centuries as inkstands: ‘Tabernaculo uno di majolica alto, nel quale sono quattro figure di rilievo, si scompone in più pezzi con colonne, et altri ornamenti et serve per calamaio’ (Oliveriana, Ms. 460, c. 89r).3 The entry highlights the original devotional role of the object, a multipart tabernacle with four figures in relief, columns and other decoration, at that time used as an inkstand. The object listed in the inventory was probably more similar to a large-scale tabernacle, such as the one with St Mark and St Luke, in the collection of Palazzo Madama in Turin (inv. no. 623/C) (Maritano 2008, pp. 32–33), than to the smaller models of chapels. However, similar changes in function are reflected in the catalogue entries of eremi, for instance, the example from the collection of the Museo di Arti Applicate in Milan. According to the museum’s archival documents, the maiolica statuette was initially called altarino, and subsequently calamaio, attesting to the shift in function from devotional to practical (Wilson 2000, p. 239).

Figure 7.

Urbino, Table Fountain with Drinking Bacchus, c. 1580, maiolica, h: 45 cm. Photograph © Catalogue of the sale of maiolica JM Béalu & Fils 2010.

The Faenza model of the chapel offers many interesting views, and different structures can be seen from the sides rather than simply from the front. Some maiolica figures were clearly meant to be viewed simply frontally, such as the statuette showing St Paul the Hermit and St Anthony the Abbot (Sarnecka 2018b, p. 271; Paolinelli 2019a), in a private collection in Cento. The group may have been inspired by a print, as the subject matter was popular in the early sixteenth century. Dürer’s workshop created a woodcut version of St Anthony Visiting St Paul in the Wilderness (c. 1503–4), which includes a stream of water flowing between the two saints, dividing the space into two sections (Strauss 1980, p. 202), very similar to the one depicted in the maiolica statuette. However, the maiolica includes many attributes of the hermit saints, such as the prominent rosary of St Anthony and the book held by St Paul, which are omitted from the print. The maiolica group includes standard elements of the scene, such as the raven that brought bread every day to the hermits. The back of the maiolica group is painted white, which suggests that it was placed in a niche. The majority of maiolica figurines, however, are finished as if to be viewed also from the back but this might not necessarily be proof of how they were actually viewed.

Movement around the eremo was certainly implied in a model of the La Verna sanctuary (in the collection of the Princeton Art Museum) (Figure 8) (Prentice von Erdberg 1961). Stylistically different from the eremi discussed thus far, this model of the sanctuary seems to have originated in a monastic context. Its form stems less from the desire to represent pious activities than from the will to emphasise spiritual links between locations, and to stress affinities between geographically distant monasteries. The beholder was invited to move around the three-dimensional visualization of a monastic complex to gain a better understanding of the spatial relationships between various structures, such as the Church of Santa Maria degli Angeli, the Upper Church (Chiesa Maggiore), the Chapel of the Stigmata, and the rock from which the water miraculously sprung. With great accuracy, the model of the La Verna sanctuary shows scenes of monastic life set in the architecture of the holy place in Casentino. It is dated to 1521, exactly ninety years after La Verna was given to the Observants, and might have been commissioned to celebrate this event (Di Miglio 1568, p. xiii). This relatively early dating also proves that maiolica models of chapels and sanctuaries were not exclusively a Counter-Reformation phenomenon, but were in use long before the Council of Trent to establish spatial and spiritual links between various locations. The model of La Verna provides multiple views and could have invited interaction beyond the mere emulation of the represented figures praying. One could narrate the daily life of a Franciscan friar by observing each figure and his movements through the sanctuary, with its combination of churches and other religious buildings set in the surrounding landscape. The behaviour of the friars demonstrates the contemplation of God through His creation, one of the key elements of Franciscan teaching (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Urbino (?), Model of La Verna Sanctuary, 1521, maiolica, h: 35 cm, w: 36 cm, d: 33.3 cm, Princeton University Art Museum, inv. no. y1929–24. Photograph © Princeton University Art Museum.

Figure 9.

Frontal View of Figure 8.

The holiness of a recognisable place, in this case the La Verna sanctuary, introduces sanctity into another space, by encouraging a mental pilgrimage. Scholars have discussed enclosed gardens as vehicles for mental pilgrimages—extensions of holy places (Rudy 2011, pp. 110–18). The concept of showing realistically the architecture of the place where St Francis received his stigmata was conveyed in larger glazed terracotta altarpieces, for instance in the Franciscan Observant church in Barga, Tuscany, attributed to Girolamo della Robbia (Gentilini 1983, pp. 218–20). The representation of La Verna was also included in other glazed terracotta altarpieces, such as the altarpiece in the Chapel of Vieri-Canigiani, Santa Croce, Florence; the Baglioni altarpiece, from the family chapel now in the Museo della Porziuncola in Assisi; as well as in the predella of the altarpiece of Rocca di Gradara, near Pesaro, the composition of which was repeated in the altarpiece for the Oratorio della Madonna del Buon Consiglio in Prato (Marquand 1922, pp. 37–38). These numerous altarpieces demonstrate that sculptural representations of La Verna, imbued with the aura of the miracle and with St Francis’s holy presence, were popular across Central Italy. It seems possible that the tradition of creating small-scale, maiolica models of sanctuaries originated from the large altarpieces that visualised such places, but which did not satisfy the need for direct sensory engagement (Figure 10). The same need nourished the pious fashion for domestic maiolica models of chapels in the second half of the sixteenth century.

Figure 10.

Side View of Figure 8.

Another glazed terracotta eremo, in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, shows St Francis surrounded by nature, contemplating the crucifix and receiving the stigmata (Figure 11) (Cambareri 2007a, pp. 61–69, on p. 67). It is likely that in this example, too, the beholder was able to contemplate the importance of La Verna sanctuary, although the connection is less explicit than in the example from Princeton. The biography of St Francis recounts that he retreated to this place two years before his death. The location was defined as a heremitorio, and St Francis’s solitude both before and after the stigmatization is one of the most important experiences in La Verna (Da Celano 1904, pp. 74–75). For generations, artists imagined the moment in which the saint received the stigmata and formulated the traditional elements of the scene (Goffen 1988; Brooke 2006, pp. 160–217, 281–83, 401–4; Rutherglen 2015).

Figure 11.

Urbino (?), Saint Francis receiving the Stigmata Italian, c. 1540, maiolica, 36.8 × 33 × 22.9 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, inv. no. 53.2912. Gift of Charles B. Barnes and W. D. Gooch, Executors of the Estate of George R. White Photograph © 2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

In the maiolica statuette, we see the Crucified Christ, but not the six-winged seraph usually depicted in the images of the stigmatization. Moreover, unlike in paintings or sculptures in relief, there are no linear rays to connect the five wounds of the Christ with the newly imprinted, miraculous openings in the flesh of St Francis. Below the maiolica Crucifix there is a skull, typically found in similar statuettes showing St Jerome but rarely included in representations of Francis’s stigmatization. It clearly references Golgotha, thus characterizing La Verna as the new mountain of salvation of mankind. Moreover, this ‘holy place’ was envisaged by God as the site of the stigmatization from the beginning of time, as Bartolomeo da Pisa describes in his De conformitate vitae Beati Francisci ad vitam Domini Iesu (Fleming 1982, pp. 7–8, n. 8). Perhaps inspired by Bonaventure, Bartolomeo da Pisa emphasized the intense spiritual contemplation of the Passion and internalization of Christ’s suffering that preceded the appearance of physical wounds on Francis’s body. Francis’s gaze, focused on the greenish tones of Christ’s body set against the spiky rocks, imbues the central scene with a religious intensity that dramatically contrasts with the sleeping figure of brother Leo (Meiss 1964, p. 21). The prominent chasm in the foreground might be a reference to the belief that when Christ died on the cross La Verna was struck by an earthquake, which created its characteristically sharp-edged landscape. Bartolomeo da Pisa noted the event as: “Nam tempore passionis, ut patet in Evangelio, petrae scissae sunt; quod singulari modo in monte isto (La Verna) apparet” (Da Pisa 1906, p. 387). This element of the maiolica sculpture would thus convey the distance between the devotee and the saintly figure depicted in the centre. The meditating person was supposed to conceal her or himself mentally inside the crevasse, so as to be isolated from the saint as decorum demanded.

The composition of the Stigmatization of St Francis is likely to have been based on one of the hugely popular prints showing the scene, which had circulated widely in Italy since the end of the fifteenth century, as single sheets or as frontispieces for the Fioretti (Sarnecka 2018b, p. 267). We know that prints were widely used for the decoration of maiolica plates, and perhaps the same holds true for three-dimensional objects modelled by the same artists (Marabotti Marabottini 1982). The spiky rock behind St Francis’s feet and the pose of friar Leo behind a prominent tree could have been based on the print by Marcantonio Raimondi after Dürer’s woodcut. It is also possible that the artist who modelled the scene of the stigmatization had access to a northern print, as they circulated widely in Italy. The Adorno family from Genoa, residents in Bruges, had a panel by Jan van Eyck showing St Francis Receiving the Stigmata (Rohlmann 1999, p. 39). One memory of the act of contemplation of Dürer’s print was described by Fra Sabba da Castiglione (c. 1480–1554), who, in a garden at the foot of the Mount Formicone, marvelled at the artist’s composition “which is certainly divine, and which had recently arrived from Germany” (Thornton 1997, p. 111). That maiolica statuettes could have derived their composition from prints has already been suggested in relation to inkstands showing St George on his horse fighting the dragon, which might have been inspired by woodcut illustrations from ‘battle books’ or other written sources (Thornton 1997, p. 165).

The object seems to facilitate a range of devotional practices. The opening to the right of the Crucifix might have been a receptacle for holy water, as in the maiolica models of chapels. It does have a little tube through which water could have flowed, but the view of the back seems to suggest that this was only to create an illusion, and perhaps to enhance the link between the holy water kept at home and water from the La Verna sanctuary. The holy water could be used to make the sign of cross, thus marking the bodily preparations for spiritual engagement with the divine. The faithful brought blessed water from their parish churches or from various shrines as a pilgrim souvenir (Brundin et al. 2018, p. 4). The water that sprang miraculously from the rock at La Verna is one of the most vivid stories from St Francis’s life, and one that clearly identifies him as the antitype of Moses and Christ. The other curious element is the structure of the back, which connects the opening to a chimney-like rock behind the Crucified Christ. It seems likely that this connection was created to allow the burning of incense and the smell would have added to the devotional experience (Sarnecka 2018b, pp. 268–69). Similarly, paper flowers could have been placed in the small holes spread across the top of the eremo (Cambareri 2007b). The glaze runs inside these holes, and therefore they must be original. It has been suggested in relation to a Florentine sculpture of St Jerome in Penitence (Ashmolean, WA 1960.64) that eighteen small holes in the rocks behind the saint ‘would presumably have held representations of trees or other vegetation’ and that these additions in terracotta or another material would have enriched the landscape (Warren 2014, pp. 483–84). Other reliefs showing the lives of saints, such as St John the Baptist from Budapest, also include holes and small trees (Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest inv. no. 1121) (Balogh 1975, no. 69, Abb. 93).

The Last Supper, in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, is another maiolica sculpture, which does not strictly belong to the group of maiolica models of sanctuaries or chapels but shares numerous key characteristics with this category (Figure 12). Most importantly, it points to the operational potential of these objects. The maiolica models of chapels and sanctuaries invited faithful owners to animate the scene by turning the object around or to project themselves into the space occupied by the saints. In the maiolica Last Supper, movement similarly informed the devotional experience. The figurines of apostles are not simply designed to be looked at, but also to be touched and re-arranged. Close examination of the glazed terracotta group reveals that the figures could be moved to a different spot and taken off their stools (Cambareri 2007a, pp. 66–67). This physical manipulation perhaps encouraged the owners to enter into the drama of the unfolding events.

Figure 12.

Faenza, The Last Supper, 16th century, maiolica, 21.6 × 32.6 × 58.1 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, inv. no. 1983.61. Bequest of R. Thornton Wilson in memory of Florence Ellsworth Wilson. © 2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Though scenes of the Last Supper are by no means unusual in Renaissance and Baroque paintings, three-dimensional representations of this subject are rather rare in the Early Modern period. Therefore, it is significant that we have another example of this iconography created in the medium of glazed terracotta, namely a relief attributed to Giovanni della Robbia based on a print after the celebrated composition by Leonardo da Vinci (Figure 13), in the Victoria and Albert Museum (Lambert 1987, pp. 198–99, cat. no. 215 and 218). Scholars argued that the relief was designed for the refectory of the Convent of San Francesco in Barga (Hess 1999, p. 13). If that was indeed the case, it would point to a similar relationship between the representations included in glazed altarpieces and in small, maiolica domestic models, as in the case of the La Verna sanctuary. The artist responsible for the Last Supper, in Boston, created a detailed composition, paying great attention to minutiae. The clear interest in realistic depictions of vases, cutlery and food recalls a still-life depicted in a fresco of the Wedding at Cana from the Church of San Nicolà in Tolentino. In the maiolica group, the vases are decorated with simple motifs of blue lines on white background, promoting the two basic colours of Renaissance ceramics.

Figure 13.

Giovanni della Robbia, The Last Supper, 1515–1520, tin-glazed terracotta, h: 55.88 cm, w: 162.56 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, inv. no. 3986:1 to 3–1856. Photograph © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The artist notably used manganese purple rather than blue to delineate the facial features, and the handling resembles, to an extent, that of Giovanni della Robbia in the Last Supper and in his smaller scale reliefs, such as the Meeting of Christ Child and Young John the Baptist (c. 1510), at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence (inv. no. 15474). Moreover, the artist responsible for the maiolica paid great attention to the modelling of the hair. The firing of individual figures is very accomplished, as there is no evidence of air bubbles or crawling. The object is executed in a technique typical for the maiolica statuettes, whereby a white glaze applied to the biscuit-fired surface provides the basis for subsequent painterly decoration. Thus, white remains visible here and there underneath the blue or yellow surfaces of the robes. However, the boundaries between different colours are well defined, for instance in the necks, which remain white planes enveloped by the colourful robes. Only in some areas glazes run during the firing and colours from the robes affected elements that were supposed to remain white. The same has happened with the blue from the vases and jars on the tables, which have run into the white surface of the tablecloth.

Almost all hands and other protruding elements of the group are intact, which suggests that the object was kept in one place for a long time. This means that it was designed for a specific location, perhaps a refectory in a convent. Certainly, the iconography of this small maiolica group would be suitable for a space where eating would take place. Every apostle is highly individualized, not only by the colour of his robes, but also through varied gestures and facial expressions; some figures are clearly amazed, others are shown in adoration or in shock. Overall, the lively atmosphere, which results from the animated responses of the apostles, seems to be rather positive. The atmosphere of conviviality and joy resultant from the meeting around the table could have inspired a similarly positive attitude among the people gathered around the object, be they friars, nuns, or laypeople.

The figures do not seem to be related to the Fontana or the Patanazzi workshops active in Urbino that were responsible for the maiolica eremi discussed above. John Mallet has suggested that the Boston Last Supper should be categorised in the bianco di Faenza class, though he stressed that it did not necessarily have to have come from the city famous for its production of high quality maiolica.4 He proposed a dating ‘quite far into the seventeenth century’, linking the convivial representation to the little-studied compendario figure-groups.5 Subsequently, Timothy Wilson has proposed that it might have been produced in Urbino around 1600.6 Wilson’s proposed dating links to the inventory of possessions in the Ducal Palace in Urbino.

5. Conclusions

The maiolica models of chapels and sanctuaries, with their complex structures and narrative encouragement, might have inspired a multisensory experience of the divine. By representing saints kneeling before the altar or contemplating a crucifix in a landscape, they provided a model for everyday pious life. Small maiolica figures seemed to reflect a fashion for mixed-media religious objects and a desire to enact devotions with religious objects that escaped simple categorization as a sculpture or a painting. They were modelled as sculptural objects but much of their expressive quality depends on their vivid colours, skillfully and imaginatively applied to the white tin-glaze covering the surface of the biscuit-fired earthenware. Both their roles in defining space and the ways in which the viewer seems to have been expected to engage with them varied. Unlike glazed terracotta altarpieces, maiolica eremi could have originally formed a part of a more intimate and private setting. Moreover, their portability and reduced scale seem to have allowed for a more immediate and physical pious experience. Although they were less lifelike than full-size effigies, they had the significant advantage of inviting handling and touch more freely than sculpted altarpieces in church. This realisation about maiolica statuettes offers a positive and revealing perspective, in which their spiritual significance, technical accomplishment, and functionality come to the fore. Della Robbia and the minor masters had complementary specialisations; each was vital for answering specific pious and aesthetic needs. This dynamic suggests a symbiosis rather than a divergence between these two artistic products. Even if they satisfied different markets and adopted different aesthetic preferences as types of objects stimulating devotional experience, both were glazed earthenware with luminous surface, and both were treasured for satisfying devotional needs and expectations. The focus on these artefacts from the perspective of technique and devotional impact, challenges unhelpful distinctions between higher and lower art.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Research Council, grant number 319475 and by the National Science Centre, Poland, grant number 2018/29/B/HS2/00575.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to Deborah Howard, Claudio Paolinelli, Carmen Ravanelli Guidotti and Bella Szala for their comments and assistance with this research. Many special thanks to Marietta Cambareri, Courtney Harris, Abigail Hykin, Valentina Mazzotti, Antonietta Epifani and Cristina Maritano for their support when examining the objects from the collections of Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza and Palazzo Madama in Turin. I am greatly indebted to the anonymous reviewer, Salvador Ryan and the editorial team.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Balogh, Jolán. 1975. Katalog der ausländischen Bildwerke des Museums der Bildenden Künste in Budapest, IV–XVIII. Jahrhundert. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsanti, Giorgio, and Francesca Piccinini, eds. 2009. Emozioni in terracotta. Guido Mazzoni, Antonio Begarelli. Sculture del Rinascimento emiliano. Modena: F.C. Panini. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, Rosalind. 2006. The Image of St Francis. Responses to Sainthood in the Thirteenth Century. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brundin, Abigail, Deborah Howard, and Mary Laven. 2018. The Sacred Home in Renaissance Italy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cambareri, Marietta. 2007a. Italian Renaissance Sculpture in Maiolica and Glazed Terracotta in the Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In La statua e la sua pelle. Artifici tecnici nella scultura dipinta tra Rinascimento e Barocco. Edited by Raffaele Casciaro. Galatina: Congedo, pp. 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cambareri, Marietta. 2007b. Label for the Maiolica St Francis. For the exhibition Donatello to Giambologna. Italian Renaissance Sculpture at the Museum of Fine Arts. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, Samuel. 2011. Renaissance Attachment to Things: Material Culture in Last Wills and Testaments. Economic History Review 65: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Celano, Tommaso. 1904. Legenda Sancti Francisci. London: J.M. Dent & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Da Pisa, Bartolomeo. 1906. De conformitate vitae Beati Francisci ad vitam Domini Iesu. In Analecta Franciscana. Italy: Quaracchi, vol. IV. [Google Scholar]

- Di Miglio, Augustino. 1568. Nuovo dialogo delle devozioni del sacro Monte della Verna. Florence: Ducal Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, Giovanni. 1860. Regola del governo di cura familiare. Edited by Donato Salvi. Florence: A. Garinei. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, John. 1982. From Bonaventure to Bellini. An Essay in Franciscan Exegesis. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galandra Cooper, Irene. 2019. Unlocking ‘pious homes’: Revealing devotional exchanges and religious materiality in early modern Naples. Renaissance Studies 33: 832–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardelli, Giuliana. 1987. A gran fuoco: Mostra di maioliche rinascimentali dello Stato di Urbino da collezioni private: Sale del Castellare di Palazzo ducale. Urbino: Accademia Raffaello. [Google Scholar]

- Gardelli, Giuliana. 1991. Urbino nella storia della ceramica: Nota sulla grottesca. In Italian Renaissance Pottery. Edited by Timothy Wilson. London: British Museum Press, pp. 126–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gentilini, Giancarlo, ed. 2008. Dal rilievo alla pittura: La Madonna delle Candelabre di Antonio Rossellino. Florence: Polistampa. [Google Scholar]

- Gentilini, Giancarlo. 1983. Le "terre robbiane" di Barga. In Barga medicea e le “enclaves” fiorentine della Versilia e della Lunigiana. Edited by Carla Sodini. Florence: Olschki, pp. 203–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gentilini, Giancarlo. 2012. Scultura dipinta o pittura a rilievo? Riflessioni sulla policromia nel quattrocento fiorentino. Technè 36: 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Giacomotti, Jeanne. 1974. Catalogues des Majoliques des Musees Nationaux, Ministère de Affaires culturelles. Paris: Editions des Musées Nationaux. [Google Scholar]

- Goffen, Rona. 1988. Spirituality in Conflict: Saint Francis and Giotto’s Bardi Chapel. University Park and London: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti, Paolo. 1976. La dimensione popolare delle targhe ceramiche devozionali e della poetica epigrafica nei tabernacoletti dell’area emiliano-romagnola. In Ceramiche devozionali nell’area emiliano-romagnola. Edited by Paolo Guidotti, Giovanni I. Reggi and Alfredo Taracchini. Imola: Galeati, p. 15ff. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Chriscinda. 2011. What makes a picture?: Evidence from sixteenth-century Venetian property inventories. Journal of the History of Collections 23: 253–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, Catherine. 1999. Maiolica in the Making: The Gentili/Barnabei Archive. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, Elena. 2003. Il Secolo d’oro della maiolica. Ceramica italiana dei secoli XV-XVI dalla raccolta del Museo Statale dell’Ermitage. Milan: Electa. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Pamela. 1988. Federico Borromeo as a Patron of Landscapes and Still Lifes: Christian Optimism in Italy ca. 1600. The Art Bulletin 70: 261–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kube, Al’fred Nikolaevič. 1976. Catalogue no. 89. In Ital’janskaja majolika XV-XVIII vekow. Sobranie gosudarstvennogo Ermitaža. Edited by O.E. Michajlova and E.A. Lapkoskaja. Moscow: Iskusstvo. [Google Scholar]

- Kupiec, Catherine. 2019. New Light on Luca della Robbia’s Glazes. In The Art of Sculpture in Fifteenth-Century Italy. Edited by Amy Bloch and Daniel Zolli. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Susan. 1987. The Image Multiplied: Five Centuries of Printed Reproductions of Paintings and Drawings. London: Abaris Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lugli, Adalgisa. 1990. Guido Mazzoni e la rinascità della terracotta nel quattrocento. Turin: Umberto Allemandi. [Google Scholar]

- Lydecker, John Kent. 1987. The Domestic Setting of the Arts in Renaissance Florence. Ph.D. dissertation, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Marabotti Marabottini, Alessandro. 1982. Fonti iconografiche e stilistiche della decorazione nella maiolica rinascimentale. In Maioliche umbre decorate a lustro. Edited by Grazietta Guaitini. Florence: Nuova Guaraldi Ed., pp. 25–57. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, Marino. 2007. Catalogue entry no. 23. In Le maioliche rinascimentali nelle collezioni della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Perugia. Edited by Timothy Wilson and Elisa Sani. Città di Castello: Petruzzi, vol. 2, pp. 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Maritano, Cristina. 2008. Catalogue entry. In Le ceramiche di Palazzo Madama. Guida alla collezione. Turin: Fondazione Torino Musei. [Google Scholar]

- Marquand, Allan. 1922. Andrea della Robbia and his Atelier. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matchette, Ann. 2006. To Have and Have Not: The Disposal of Household Furnishings in Florence. Renaissance Studies 20: 701–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotti, Valentina. 2018. 13 Maggio 1944: La distruzione e la rinascita del MIC di Faenza. Lo Stato dell’Arte 16: 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Meiss, Millard. 1964. Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Frick Collection. New York: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, Margaret. 2007. Creating Sacred Space: The Religious Visual Culture of the Casa in Renaissance Venice. Renaissance Studies 21: 151–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negroni, Franco. 1998. Una famiglia di ceramisti Urbinati: I Patanazzi. Faenza 84: 104–15. [Google Scholar]

- Niccoli, Ottavia. 2001. Bambini in preghiera nell’Italia fra tardomedioevo ed età tridentina. Quaderni di storia religiosa 8: 273–99. [Google Scholar]

- Niccoli, Ottavia. 2014. Pregare con la bocca, con gli occhi e col cuore nell’Italia della prima età moderna. The Italianist 34: 418–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleotti, Gabriele. 2002. Discorso intorno alle immagini sacre e profane (1582). Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Palvarini Gobio Casali, Mariarosa. 2000. Ceramiche d’arte e devozione popolare in territorio mantovano. Mantua: Publi Paolini. [Google Scholar]

- Paolinelli, Claudio. 2014. Lacrime di smalto. Plastiche maiolicate tra Marche e Romagna nell’età del Rinascimento. Ancona: Il Lavoro Editoriale. [Google Scholar]

- Paolinelli, Claudio. 2019a. Gruppo plastico con San Paolo Eremita. e sant’Antonio Abate. In La Grazia dell’Arte. Collezione Grimaldi Fava. Maioliche. Edited by Carmen Ravanelli Guidotti. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, pp. 68, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Paolinelli, Claudio. 2019b. L’aquila e la quercia. Maioliche al Palazzo Ducale di Urbino. In Raphael Ware. I colori del Rinascimento. Edited by Timothy Wilson and Claudio Paolinelli. Turin: Umberto Allemandi, pp. 12–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pia Mannini, Maria. 1981. Immagini di devozione. Ceramiche votive nell’area fiorentina dal XVI al XIX secolo. Milan: Mondadori Electa. [Google Scholar]

- Piccini, Alberto. 2002. I calamai dei Mazzoni. Fimantiquari Arte Viva 30: 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice von Erdberg, Joan. 1961. Outstanding Maiolica at The Art Museum, Princeton University. The Burlington Magazine 103: 299–305. [Google Scholar]

- Rackham, Bernard. 1940. Victoria and Albert Museum. Catalogue of Italian Maiolica. London: Board of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Ravanelli Guidotti, Carmen. 1998. Thesaurus di opere della tradizione di Faenza nelle raccolte del Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza. Faenza: Agenzia polo ceramico. [Google Scholar]

- Reale, Giovanni, Andrea Samaritani, and Elisabetta Sgarbi. 2008. Il pianto della statua nelle sculture sacre in terracotta di Niccolò dell’Arca, Guido Mazzoni e Antonio Begarelli. Milan: Bompiani. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlmann, Michael. 1999. Flanders and Italy, Flanders and Florence. Early Netherlandish Painting in Italy and its Particular Influence on Florentine Art: An Overview. In Italy and the Low Countries. Artistic Relations. The Fifteenth Century. Edited by Victor Schmidt. Florence: Centro Di, pp. 39–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rudy, Kathryn M. 2010. Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer. Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 2: 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudy, Kathryn M. 2011. Virtual Pilgrimages in the Convent. Imagining Jerusalem in the Late Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Rudy, Kathryn M. 2017. Eating the face of Christ: Philip the Good and his physical relationship with Veronicas. In The European Fortune of the Roman Veronica in the Middle Ages. Edited by Amanda Murphy, Herbert L. Kessler, Marco Petoletti, Eamon Duffy and Guido Milanese. Convivium: Supplementum, pp. 169–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherglen, Susannah. 2015. “The Footprints of Our Lord”: Giovanni Bellini and the Franciscan Tradition. In In a New Light. Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert. Edited by Susannah Rutherglen and Charlotte Hale. New York: The Frick Collection, pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sangiorgi, Fert. 1976. Documenti urbinati: Inventari del Palazzo Ducale (1582–1631). Urbino: Accademia Raffaello. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnecka, Zuzanna. 2018a. “And The Word Dwelt Amongst Us”. Experiencing the Nativity in the Italian Renaissance Home. In Domestic Devotions in Early Modern Italy. Edited by Maya Corry, Marco Faini and Alessia Meneghin. Leiden: Brill, pp. 163–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnecka, Zuzanna. 2018b. Le piccole sculture maiolicate e il loro significato nelle case marchigiane del primo Cinquecento. In Pregare in Casa. Edited by Cristina Guarnieri, Giovanna Baldissin Molli and Zuleika Murat. Rome: Viella, pp. 265–78. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Walter. 1980. The Illustrated Bartsch. New York: Abaris Books, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, Dora. 1997. The Scholar in His Study. Ownership and Experience in Renaissance Italy. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, Dora, and Timothy Wilson. 2009. Italian Renaissance Ceramics: A Catalogue of the British Museum Collection. London: British Museum Press, vol. 2, cat. no. 213. [Google Scholar]

- Turchini, Angelo. 1980. Tracce di religione domestica in ambiente urbano: Il caso di Rimini fra il XV e il XVII secolo. Il Carrobbio 6: 351–64. [Google Scholar]

- Venturi, Adolfo. 1889. Il testamento di Guido Mazzoni detto il Paganino o il Modanino. Archivio storico dell’arte 2: 155–57. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Jeremy. 2014. Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture. A Catalogue of the Collection in the Ashmolean Museum. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum Publications, vol. 2, pp. 482–87. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Jeremy. 2016. The Wallace Collection. Catalogue of Italian Sculpture. London: Trustees of the Wallace Collection, pp. 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Wendy. 1986. Italian Renaissance Maiolica from the William A. Clark Collection. London: Scala Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Timothy. 1996. Italian Maiolica of the Renaissance. Milan: Bocca Editori. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Timothy. 2000. Catalogue entry no. 247. In Musei e Gallerie di Milano. Museo di Arti Applicate. Ceramiche. Edited by Raffaella Ausenda. Milan: Mondadori Electa, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Timothy. 2016. Maiolica: Italian Renaissance Ceramics in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Timothy, and Elisa Sani. 2007. Le maioliche rinascimentali nelle collezioni della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Perugia. 2 vols. Città di Castello: Petruzzi. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Timothy. 2017. Italian Maiolica and Europe. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum Publications, pp. 368–79. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Some exceptional examples, when the maker is specified, include Fra Saba’s bust of St John the Baptist by Donatello (Thornton 1997, pp. 106–7) and two terracotta figures by ‘Benedetto ischultore’ (Benedetto da Maiano) acquired by Luigi Martelli in 1489 (Lydecker 1987, p. 127). |

| 2 | Samuel Cohn discussed this practice in detail and linked it to the post-Black Death mentality to protect goods from entering the general market and ensuring that they remain among family possessions or within repositories of the Church. |

| 3 | I am very grateful to Claudio Paolinelli for making me aware of the document. The transcription is mine. |

| 4 | Letter from John Mallet to Marietta Cambareri preserved in the object file at the MFA, dated 1998. |

| 5 | Ibid. |

| 6 | A written record of an oral communication with Professor Timothy Wilson during his visit at the MFA in September 2001. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).