Abstract

Shrine-visitation (ziyāra) and devotion to Muḥammad (such as expressed in taṣliya, the uttering of invocations upon the Prophet), both expressed through a range of ritualized practices and material objects, were at the heart of everyday Islam for the vast majority of early modern Ottoman Muslims across the empire. While both bodies of practice had communal and domestic aspects, this article focuses on the important intersections of the domestic with both shrine-visitation and Muḥammad-centered devotion as visible in the early modern Ottoman lands, with a primary emphasis on the eighteenth century. While saints’ shrines were communal and ‘public’ in nature, a range of attitudes and practices associated with them, recoverable through surviving physical evidence, travel literature, and hagiography, reveal their construction as domestic spaces of a different sort, appearing to pious visitors as the ‘home’ of the entombed saint through such routes as wall-writing, gender-mixing, and dream encounters. Devotion to Muḥammad, on the other hand, while having many communal manifestations, was also deeply rooted in the domestic space of the household, in both prescription and practice. Through an examination of commentary literature, hagiography, and imagery and objects of devotion, particularly in the context of the famed manual of devotion Dalā’il al-khayrāt, I demonstrate the transformative effect of such devotion upon domestic space and the ways in which domestic contexts were linked to the wider early modern world, Ottoman, and beyond.

1. Introduction

On a verdant hill in Istanbul’s ritzy Beşiktaş district, overlooking the Bosphorus Straits, is a complex of buildings with a dome-covered saint’s shrine at its center, akin in basic form and function to Islamic saints’ shrines in diverse circumstances the world over (Mulder 2014; Petersen 2018). Underneath is buried one of the most popular Muslim saints of the city, Haẓret-i Yaḥyā Efendi (1494–1570), his tomb marked by a large cenotaph, with the smaller cenotaphs of family members and important disciples clustered around him.1 On almost any given day of the year the chamber under which he lies buried is frequented by devotees who have come to venerate the saint and to ask for his intercession with God. According to early modern authorities such as the historian Peçevī (1574–1649), his popularity first emerged during the saintly shaykh’s lifetime, the ‘great and small’ bringing votives and other gifts to his sufi lodge, around which, according to Peçevī, Yaḥyā Efendi planted the many trees whose descendants still mark the place today amidst the concrete sprawl of modern Istanbul (Peçevî 1864–1866, pp. 455–546). Another early modern visitor to the saint, the famed traveler Evliyā Çelebi (1611–c. 1683), noted that ‘upon the summit of a tall hill close to the sea, within an exalted domed chamber (kubbe), is the burial place [of Yaḥyā Efendi], a shrine (āsitāne, lit. ‘threshold’) whose four walls have been covered by how many thousands of passionate lovers (‘uşşākān) able to write with all manner of couplets of poetry (Evliyâ Çelebi 1996, p. 222).’

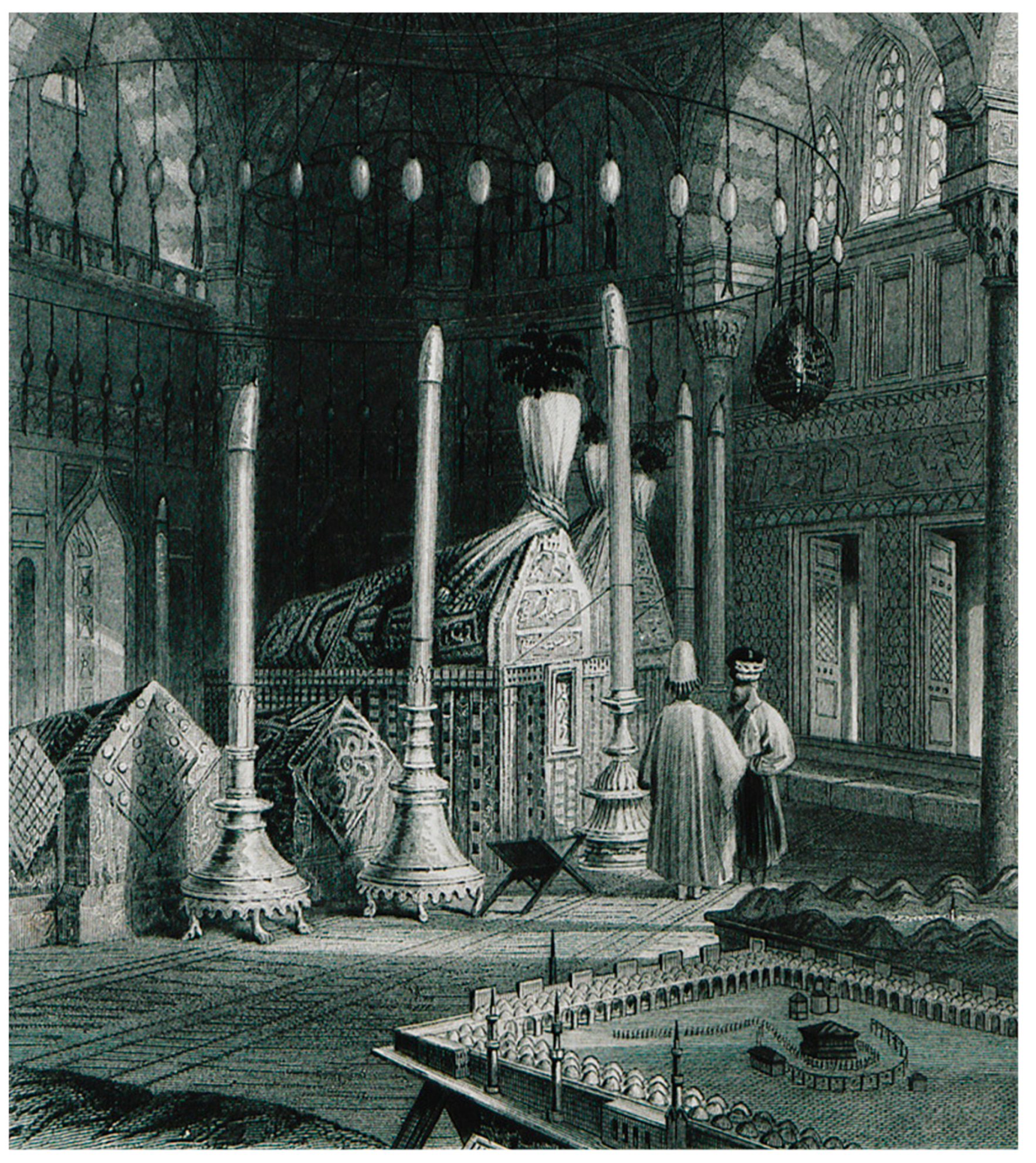

Indeed, should you visit the shrine today, once you had surveyed the busy Baroque and later decorative scheme of the interior, your eyes might fall upon the still quite legible remnants of these ‘thousands’ of verses. Now, fortunately preserved behind plexiglass sheets, not just ‘couplets of poetry’ but short prayers, names, and dates can be read, most having been written in neat, clear naskh. Some are in carefully voweled Arabic, others in Ottoman Turkish (Figure 1). While many of the inscriptions that must have once covered these walls are now gone, enough remain that while perusing them one begins to sense that despite being a communal and quite public structure, this domed room has also long been experienced as an intimate, personal, and even domestic space. Perusing this open archive of past devotees, you might begin to understand why the Arabic word ziyāra is used to describe both pious visits to such a holy place as well as for visits to the home of a friend.

Figure 1.

Examples of the wall-writing in the shrine of Yaḥā Efendi, here showing examples in both Arabic and Ottoman Turkish, compositions both original and reproducing other texts, particularly the Qur’an. One of the inscriptions, in the left photo, is dated AH 1015/1606-7. Photos by the author.

Were you to go back in time to eighteenth century Beşiktaş to visit the shrine of Yaḥyā Efendī and then accompany home one of the visiting devotees, odds are good that within her home you would find a copy of the ubiquitous devotional manual Dalā’il al-khayrāt, a compilation of prayers and blessings upon the Prophet Muḥammad (ṣalāt ʿalā al-nabī); if not the Dalā’il, then perhaps another, similar compilation of devotion to Muḥammad, in Arabic or in Ottoman Turkish (or both). Historically, devotion to Muḥammad has been expressed in many different ways across the Islamicate world. Amidst them all, the most fundamental was—and remains—the practice sometimes referred to in Arabic as taṣliya, that is, prayer for God’s blessing upon Muḥammad, most succinctly expressed in the frequently invoked and foundational invocation, ‘May the peace and blessing2 of God be upon him (that is, Muḥammad).’ Out of this short phrase an almost endless body of devotional material has been elaborated, the Dalā’il al-khayrāt becoming the most important and widespread textual iteration of such devotion (Rippen 2010; De La Puente 1999; Padwick 1961; see Appendix A for a sample translation from the text). In conversing with your early modern host you might learn that in addition to the daily ritual prayers and pious visits to the shrines of the saints, such litanies of blessing and prayer upon Muḥammad made up a central part of her family’s devotional life, crucial constitutive components of what it meant in fact to ‘be Muslim.’ Unlike the visits to the saints or the performance of the obligatory ritual prayer in a mosque,3 such devotion to Muḥammad frequently took place inside their home, often upon waking from sleep or before going to bed, and so within the most intimate precincts of the house.

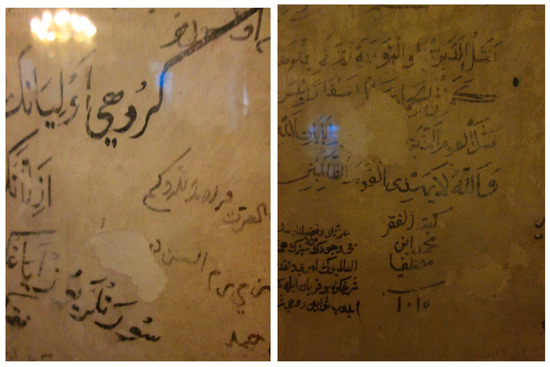

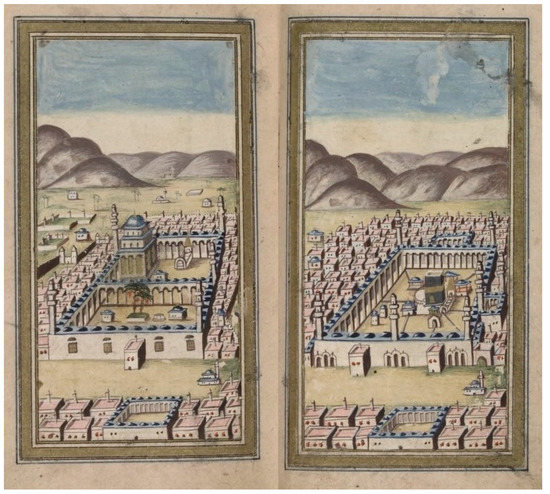

Domestic devotion to Muḥammad was not limited to the textual and aural. If you were to examine the family’s copy of the Dalā’il you might be struck by colorful depictions of the holy places and objects of the Ḥijāz such as Mecca’s Ka’ba or the minbar of Muḥammad in Medina, the style of the painting possibly reminding you of early modern Western European art conventions (Figure 2). You might also note within such a book or upon one of the walls of the home a curious calligraphic composition, a ḥilye-i şerīf, a verbal icon of the Prophet (Figure 3). Families of more modest means might have a less artistically refined but still ‘functional’ printed copy, with little roundels showing Mecca and Medina as well. Finally, perhaps your host would modestly relate to you that Muḥammad himself had once visited her home, in a dream-vision or even in ‘waking life,’ as a reward for the household’s daily acts of devotion and love towards him. Perhaps she would ask you to smell deeply and see if you could still detect the sweet scent of musk that his footsteps had left behind. Bidding farewell to your pious host, you muse on the fact that similar households exist all across the Ottoman Empire in multiple linguistic settings, and beyond, little drops of devotion that together constitute a vast sea of early modern devotion to the Prophet.4

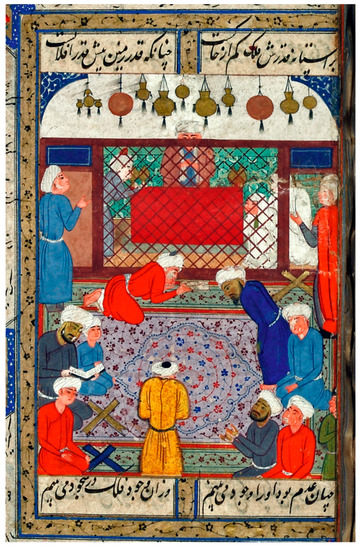

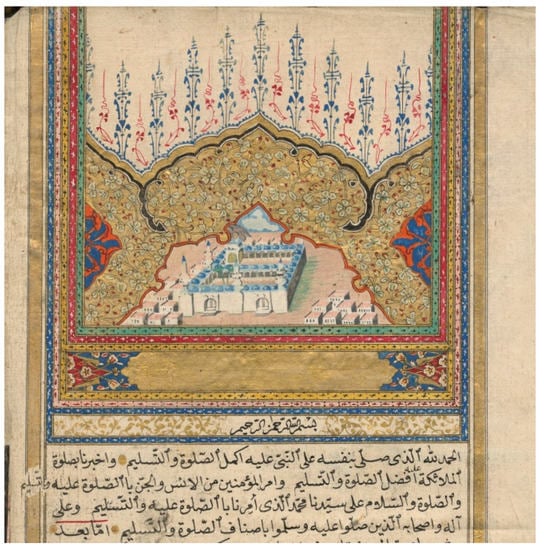

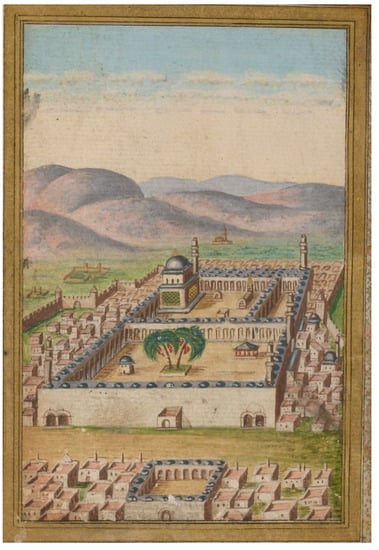

Figure 2.

Cavalier perspectival views of Mecca (right) and Medina, from a 1772 copy of the Dalā’il al-khayrāt, the body of the text written by one Ḥāfiẓ Muḥammad ibn Ḥāfiz Ibrāhīm Mevlevī, imām of the Murādiye Camii in Edirne. Library of Congress, BP183.3.J39 1772 Arabic MSS, fol. 23b-24a.

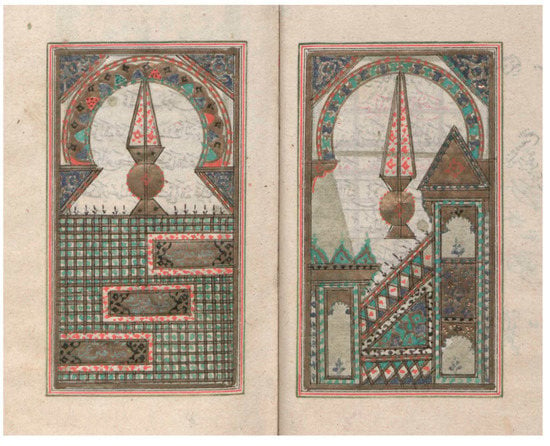

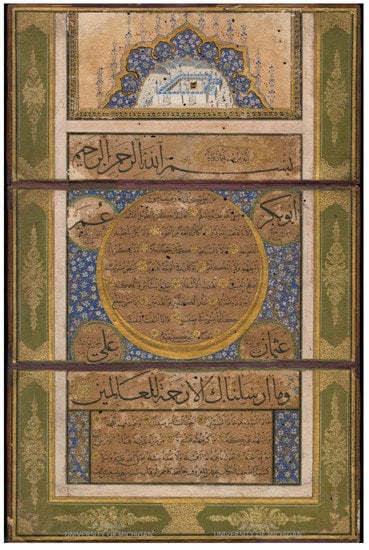

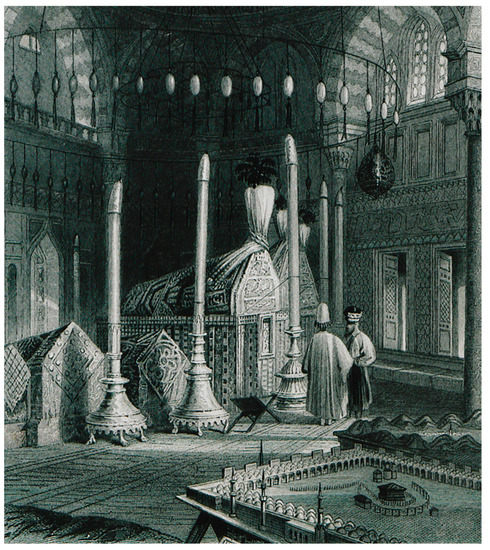

Figure 3.

A ḥilye-i şerīf, with Ottoman Turkish interlinear translation, completed by by Ismāʿīl Bagdādī in 1756/57, added to a somewhat earlier copy of the Dalā’il. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Arabe 6859 i., folio 5v.

These two sites of Ottoman Islamic devotion—the communal space of the saint’s shrine, and the domestic space of the home of an ordinary Ottoman household—with their associated practices do not at first glance seem to have had much in common beyond their centrality within the daily religious life of Ottoman Muslims. Yet on closer analysis these two sites and ritual bodies of devotion prove to have been connected through a dialectic of domestic and communal, open and closed. The communal, outwardly opened space of the saint’s shrine incorporated aspects of the domestic, while the devotional regimes of the more inward facing and restricted access household brought close distant holy sites and presences within the space of the home. Practices of shrine visitation drew elements of the home into the holy place, while practices of devotion to Muḥammad brought the effacious traces of the holy places into the home. Ottoman Muslims sought to perpetuate their own personal presence in the vicinity of the holy dead even after they had physically left the shrine. Similarly, they strove to reproduce the Prophetic presence in their households through acts and material objects of devotion. Both broad bodies of practice were linked to each other through shared sensual and imaginative regimes that drew upon touch, smell, taste, sight, and hearing; and both were as much the domain of women as of men, resisting neat gendered categorizations.

To be sure, definite differences distinguish the devotional regimes of the shrine and the domestic household from each other, even if, as in other early modern contexts, such distinctions can only do so much work (Faini and Meneghin 2019, pp. 5–17). The shrine to which devotees made pious visitation was (and remains) oriented around a particular saint who was (usually) physically present in the form of his or her entombed body beneath a magnificent (or modest) cenotaph or another marker. When it was open, people could come and go from the shrine as they pleased, lighting candles, depositing votives, sprinkling incense. Often part of a larger complex, the shrine might have benefited from endowments and the oversight of a caretaker, or it might have been under the supervision of a community of sufis and their shaykh. In short, it was in many ways a resolutely communal and public space. By contrast, while devotion to Muḥammad certainly had public, communal forms (Katz 2007; Krstic 2011, pp. 32–35; Allen 2019a), some quite prominent, such as the great mevlid rituals Ottoman sultans regularly held, in both prescriptive form and in actual daily practice taṣliya and other forms of devotion to the Prophet were frequently domestic in setting. They frequently took place within the relative privacy of a house or in the private rooms contained within a madrasa, sufi lodge, or bachelor housing (Allen 2019b). The associated devotional texts and images were abundantly produced and relatively affordable even before the rise of typographic print in the nineteenth century, and for Turkish-speaking Ottomans the core Arabic prayers such as those of the Dalā’il were often supplemented by translations and glosses in Ottoman Turkish, as well as various independent works of devotion composed in that language. The visual repertoire of images that developed within the Dalā’il and in other contexts did not require any sort of aural performance; rather, such images ‘worked’ through presence alone, with sight, imagination, and tactile participation additional modes of interaction, all especially suited for household use. In short, if we wanted to isolate the most typically domestic form of Islamic religious life in the early modern world, there is little else for which as strong a case could be made as these texts, rituals, and associated materialities of devotion to Muḥammad.5

As central aspects of Ottoman Islamic identity and practice, there are many possible routes of analysis for understanding saints’ shrines and household devotion to Muḥammad, even from within the frame of the domestic. What I deal with here is but a selection. For the shrine, I have singled out the discrete practice of pious wall-writing, not only for its importance in shrine visitation, but also because it has been scarcely recognized in historical scholarship before. However, in thinking about the domestic aspects of the shrine, I have also sought to uncover some of the other constitutive practices and spatial imaginations of a more abstract nature, suggestive of how early modern Ottomans experienced the space of the shrine generally. So, my treatment of shrine visitation begins with an investigation into the spatial and imaginative constitution of shrines as ‘homes’ of saints, the context within which wall-writing and its social functions unfolded. As for domestic devotion to Muḥammad in the home, while taking into account other devotional texts and objects, I have centered my analysis on the Dalā’il al-khayrāt in its diverse forms as a means of ritual performance in a domestic setting,6 as the subject of commentary works, and as a setting for devotional imagery and ensuing forms of participation (Abid 2017). I show how practices and imagery that originated in more communal, ‘public’ contexts became, in the early modern period, ‘domesticated,’ moving in some cases quite literally from the walls of mosques to material substrates within family homes, the varieties of participation oriented around these objects changing in the process. Where the act of wall-writing and other forms of shrine visitation cemented people’s ties to a saint’s shrine, aural, tactile, and visual repertoires of devotion to Muḥammad entailed making the distant holy places of the Ḥijāz a part of everyday life within domestic space, and in so doing, ‘prepared the ground’ for realizing the powerful presence of Muḥammad himself within individual Ottoman households.

In what follows, I have generally limited my analysis to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, looking further back at some points in order to uncover the genealogies of certain practices, texts, and images. I could have pressed much further back, to be sure: The history of the veneration of the saints goes back much further, while the space of the home already possessed significant resonances and meanings stretching far back into the Islamic past (Campo 1991), a heritage upon which the early modern transformations in devotional practice could build. Instead of focusing on a single location within the empire, I have drawn upon a diverse range of contexts from across the empire (though Constantinople and Damascus dominate) in both Arabic and Ottoman Turkish. While I have tried to take some note of regional particularities and points of divergence, I contend that out of all of this evidence a distinctly Ottoman pattern of devotional life and imagination emerges. While its ultimate shape was distinctly Ottoman, this pattern of devotional life was forged with resources from the wider Afro-Eurasian early modern world, Muslim and non-Muslim, important aspects of which appear in this article in the form of texts originally produced in the Maghrib. Ottoman Muslim devotional life existed alongside and in contact with devotional cultures and currents prevailing in the other religious communities of the empire and beyond the empire, such that connections and parallels with devotional practice in Christian Europe and those of Muslim Ottomans can often be descried. My thinking has benefited from both the existence of such parallels and of the scholarship, much of it relatively recent, centered on domestic devotion in Christian Europe. While scholars such as Torsten Wollina and Marion H. Katz (both contributers to the recent Brill volume Domestic Devotions in the Early Modern World) have examined the intersection of Islamic devotion and domestic spheres, neither devotional life in its communal or domestic aspects, nor domestic religious practice in all its forms have received anything like the degree of coverage afforded in the historiography of Western Christianity (Wollina 2019; Katz 2019). While a thorough analysis is beyond the scope of this article, I will return in the conclusion to a consideration of wider early modern connectivities and contexts within which Ottoman Islamic practices of shrine visitation and household devotion inhered.

2. The Saint’s Shrine as a Domestic Space: Practices and Imagination

Nestled within the barren stony desert that rises precipitously from the western shore of the Dead Sea towards Jerusalem is a sprawling shrine complex known as Nabī Mūsā, the rugged expanse of exposed stone surrounding a world away from the verdant environs of Yaḥyā Efendi above the Bosphorus (Figure 4). Within the complex of courtyards and domed rooms is a tomb that devotees venerate as the final resting place of the Prophet Moses—Mūsā in Arabic—conveyed by God from his place of death on the other side of the Jordan to this now numinously charged hilltop in the color-streaked and mostly empty desert (Aubin-Boltanski 2005; Aubin-Boltanski 2013).

Figure 4.

The shrine of Nabī Mūsā viewed from a subsidiary shrine uphill from the main complex. Photo by the author, October 2017.

Yet from the medieval period to the present, Muslim pilgrims from near and far have made the journey across the desert hills to this shrine in order to commune with the spirit of Nabī Mūsā, the Interlocuter of God (Kalīm Allāh) as he is called in the Qur’an. One of the many such pilgrims to this place was the great shaykh, saint, and scholar of Ottoman Damascus, ʿAbd al-Ghanī al-Nābulusī (1641–1731) (Sirriyeh 2005; Allen 2019b, pp. 366–439). Along with a party of companions he made his way from Jerusalem to Nabī Mūsā in April of 1690, during the course of a two-and-a-half-week sojourn in the holy city. His account of the shrine and his pilgrimage to it in his travel narrative al-Ḥaḍra al-unsīya fī al-riḥla al-Qudsīya includes a substantial discussion of its authenticity, the final resting place of Moses having long been contested among Muslim scholars.7 Alongside, and in support of, al-Nābulusī’s arguments for the genuine nature of the tomb are his descriptions of his own emotional and spiritual reactions to the shrine as well as those of his companions.8 He records the lines of a praise-poem (qaṣīda), which he composed on the spot and inscribed ‘upon the qibla-facing wall so that their trace (athar) might persist there.’ He then goes on to describe how ‘there was with us a pious man from the folk of Egypt, named Shaykh ʿAlī ibn ʿAlī al-Dayṣṭī,’ from the village of Dayst,

- a village from among the villages of rural Egypt. He was illiterate, neither reading nor writing. But he said [to us]: “Write in this place from my memory [the following lines],

- Good, all of it, is for those who bear hardship procured/ and the everlasting Garden is for those who in kindness are overcome.

- I am a friend to people who say, ‘For me proper deportment is required.’/Walk uprightly, and eyes and hearts will watch over you!”

(al-Ḥaḍra al-unsīya, pp. 224–25)

Before returning to shrine wall-writing itself, we must consider some of the ways in which Ottoman Muslim saints’ shrines were deeply imprecated in the domestic, both in terms of everyday practices of veneration and in the ways in which these spaces were imagined and depicted. Ottoman devotees of the saints understood the saint’s shrine as his or her house, containing not just the departed saint’s body, but also his or her continuing presence, which simultaneously required certain practices while opening up the space to other possibilities. Most important in Ottoman Islamic practices of saint veneration was bodily proximity to the entombed saint accompanied by inner right intention, outward action honoring the saint (at a minimum, reciting the opening sura of the Qur’an, the Fātiḥa, for the soul of the saint), and the aural or inward seeking of his blessing and intercession. Just as one would act in certain ways when visiting an ordinary person’s home, maintaining proper adab—here, behavior—in visiting the home of the departed saint was equally important.9 A brief clarification of the (usual) spatial arrangement of an Islamic saint’s shrine is helpful here: As might be surmised from our ‘visits’ to the tombs of Yaḥyā Efendi and Nabī Mūsā, at the center of the shrine was the tomb of the saint himself (and sometimes herself, though female saints have generally been significantly less common in Islamic milieus than in most Christian ones), almost always marked by a cenotaph, the saint’s body being interred in the earth below (see Figure 5). Unlike practices of saint veneration in some other religious traditions, which emphasize the production, dispersal, and display of bodily relics, the bodies of Muslim saints have generally been preserved whole, veiled, as it were, by being buried, not displayed in the way a Catholic or Orthodox saint might be. In this regard, we may detect a certain partial homology between the inner portion of a house—the ḥaram—to which access is relatively restricted, with the saint being at once accessible and innaccesible. Regardless, in the (usual) absence of direct physical contact, the power of the saint’s bodily presence in his tomb was filtered up and out, as it were. His physically grounded baraka (roughly, divinely bestowed power) was transmitted through the material of the shrine’s components, including in many cases the very earth thereabouts. While a saint might visit a devotee in a dream, and a devotee might take away some soil or other artefact of proximity from the tomb, it was here in the saint’s ‘house’ that he was most powerfully present and encountered, even if veiling intervened.

Figure 5.

A typical shrine layout, a depicted in a c. 1550 copy of Kulliyat-i Mawlānā Ahlī Shirāzī: While this image hails from the Safavid world, it nicely reflects architectural conventions and practices common to the Ottoman lands. Note the presence of women alongside men behind the grill marking the saint’s tomb. David Collection, Inv. no. Isl 161.

Because of the extent of his own writings and his deep investment in both venerating the saints and in defending that veneration from opponents, ʿAbd al-Ghanī al-Nābulusī provides us with especially useful evidence of such homologies between domestic home and saint’s shrine. During the second half of his life, he and his family lived in Damascus’s Ṣalāḥiyya quarter, practically next door to one of the most important and widely venerated saints of the Ottoman world, Muḥyī al-Dīn ibn al-ʿArabī (1165–1240). While today perhaps best known for his doctrine of the ‘unity of existence,’ for early modern Ottomans, Ibn ʿArabī was first and foremost a powerful saint of God, a status reflected in al-Nābulusī’s relationship with the saint. While al-Nābulusī was a major exponent and exegete of Ibn ʿArabī’s works, he also regarded the ‘Greatest Master’ as his intimate friend, visiting his ‘home’ regularly. The saint once even appeared to al-Nābulusī in a dream as being present in the latter’s own house (al-Ghazzī 2012, p. 487). Al-Nābulusī would visit the saint’s shrine every Tuesday before going to his regular teaching session, asking Ibn ʿArabī’s permission before entering and leaving, in accordance with good adab. Once, al-Ghazzī writes, Ibn ʿArabī spoke audibly to al-Nābulusī from within the tomb, and even more extraordinarily, twice al-Nābulusī transcended the usual boundary between devotee and saint’s physical body, first by placing a branch of myrtle in the miraculously outstretched hand of Ibn ʿArabī, another time by kissing the same outstretched hand (al-Ghazzī 2012, p. 519).10 In a long dream-vision that al-Nābulusī records in a compilation of visions and spiritual ‘conversations’ with God and departed saints, he describes asking Ibn ‘Arabī with his ‘spiritual tongue (al-lisān al-ruḥānī)’—and receiving an answer from within the tomb—concerning proper bodily deportment when visiting the saint (al-Ghazzī 2012, pp. 528–29).

While, like al-Nābulusī, many pious visitors sought to display proper deportment in visiting a saint’s shrine-home, such concerns existed alongside another important aspect of the shrine: Its openness to practices and social arrangements quite different from that of most other public, communal spaces. Much as a visit to a friend’s home might entail the enjoyment of food, drink, poetry, and music, shrines, especially more prominent ones, were often decidedly ludic and even sensual spaces. Candles, lamps, incense burners, and rich and colorful textiles filled these spaces, devotees themselves often contributing such objects on their visits. Aurally, the air would be filled with the sounds of Qur’an recitation, the prayers and supplications of visitors, poems, songs, and conversation (even as some devotees such as al-Nābulusī might seek quiet converse with the saint). Also, to the great ire of the puritanical opponents of saint veneration, men, women, and ‘beardless young men’ mixed quite freely in the saint’s presence, suggestive in a different and potentially troubling way of the inner precint of the shrine as analogous to the inner spaces of the domestic house (Allen 2019b, pp. 298–321).

The movement of a saintly shaykh from the house he inhabited during life to the ‘house’ he inhabited upon death entailed some changes of practice and attitude, to be sure, on the part of devotees. Yet, in other ways, the movement was interpreted almost as if it were simply a matter of transferring from one room to another. In the menāḳıb (from Ar. manāqib: The rough equivalent of a saint’s vitae in the Western Christian tradition) of Şeyh Ḥasan Ünsī (1643–1723), a saintly shaykh of Constantinople’s Hoca Paşa neighborhood, the disciple and memorializer of the saint Ibrāhīm Hāṣ describes how even after his death the saintly shaykh remained active in his disciples’ lives much as he had during his bodily life, the saint’s ‘room’ now being the free-standing türbe (that is, tomb) that was part of the dervishes tekke (communal lodge) complex:

Even now someone who has a fearful matter or a difficult thing or a problem will go to the venerable Shaykh’s noble türbe with honor and, practicing honor and graciousness, with etiquette will recite, for the dissolution of the problem will recite the [Sura] Ikhlāṣ three times and the Fātiḥa once before [the saint’s] pure spirit, give [the reward] to his noble spirit, and no sooner than leaving the türbe the solution to that person’s problem will present itself to the heart, with God’s permission, and provided the person’s intention is pure.(Hasan Ünsî Halvetî ve Menâkıbnâmesi, 351)

Sometimes the overlap of the domestic and the saint’s shrine went from the homologous and imaginal to quite literal: For instance, the great early Ottoman saint and sufi of Cairo, ʿAbd al-Wahhāb al-Shaʿrānī (1492/3-1565) (Winter 1982; Sabra 2006), buried his preceptor-shaykh and father-figure ʿAlī al-Khawwāṣ within his familial zawiya (another type of sufi ‘lodge’). After the burial of two of his sons therein, he sealed off the tomb-space to preserve a measure of exclusivety (though he himself would be buried there as well). Such burials in one’s family zāwiya in this manner was not uncommon in the Ottoman world and beyond (al-Shaʿrānī 2005, pp. 303–4). Two centuries later, in the village of Tillo in linguistically complex lands of what is now southeast Turkey, the scholar and lover of the saints Ismāʿīl Ḥaḳḳı (1703–1780) would oversee the construction of an architecturally innovative tomb-shrine directly incorporating the house of his beloved sufi master, the saint Şeyh Faḳīrallāh, preserving the memory of the saint’s home in both textual and diagramic form as well (İbrâhîm Hakkı 1914, pp. 507–8; Michot 2015). In both cases, the actual domestic spaces of the saints directly overlaid the space of their shrine-tombs in death, a pattern that drew ultimate inspiration and authorization from that of none other than Muḥammad, who was buried in his home, a home that gradually became a full-fledged shrine and prototype for many to come.

Lived domestic space and the space of the saint’s tomb could intersect in other rather literal ways as well. Ibrāhīm Hāṣ describes the living arrangements of the türbedār, the dervish who oversaw the shrine and its use, as consisting of a room (oda) attached to the türbe itself, an arrangement that would have been found in other places as well. In two stories of türbedārs, Ibrāhīm suggests how the relationship between the türbedār’s room and the inner prescint of the saint was supposed to work: In the first story, Ibrāhīm relates how the first türbedār of the shrine, a Dervish ʿAlī, used in summer to sleep within the türbe itself instead of in his designated room next to it, for the very quotidian reason of a flea infestation in his room. When asked why he eventually stopped this practice, ʿAlī replied that he kept seeing the saint in his dreams, brandishing a club and commanding him to stop sleeping there; over time this repeated vision had its effect, ʿAlī evidently suffering through the fleas as best he could (İbrâhîm Hâs 2013, pp. 303–4). ʿAlī had infringed on the special inner space of the saint, an intrusion that violated proper adab, akin to a subordinate member of a regular household deciding to sleep next to the head of the household (the presence of fleas—and the scratching and ensuing potential production of ritual impurity—excaberating the offense). That the türbedār was essentially part of the saint’s household is suggested in the second story, in which a later türbedār, Derviş Yūsuf, was asked if he had ever experienced any ‘signs’ of Ḥasan Ünsī’s sainthood, to which he replied,

Derviş Yūsuf left the türbe for a few days and wandered the city, ‘my mind remaining therein,’ but upon his return, the saint was evidently pleased with his repentance and restored him to health. The foreshortening of the saint’s domestic space and that of his devotees could be perilous if one were not careful.One day through the weakness of the flesh I commited a sin. That night I was lying in the türbe [attached] room, and I saw [in a dream] that Shaykh Ḥasan Ünsī had been manifest forth from his türbe. In his hand was a staff. With majesty and anger he advanced against me. So I went into the mosque, but I saw him following behind me! Awakening I was full of fear and took refuge in God.(Hasan Ünsî Halvetî ve Menâkıbnâmesi, 305)

3. Perpetuating Presence in the House of the Saint: The Role of Pious Wall-Writing

If a shrine custodian had the privilege—or burden, as the case may be—of literally inhabiting the domestic space of the entombed saint, other visitors had to come and go.11 Fortunately, in shrine wall-writing, devotees had potential access to a practice that allowed them to inscribe themselves into the space of the saint and to maintain a personal anchor in that space long after returning home. If in the modern world such personalized, officially unauthorized inscriptions would be classified as graffiti and potentially give grounds for prosecution, in the pre-modern Islamicate world, as in much of the rest of the pre-modern world, writing on public or semi-public substrates was not just tolerated but was an expected, indeed valorized, means of participating in public and especially sanctified spaces. Historians have, in the last few years, begun to realize the sheer extent and research potential of ‘authorized graffiti’ (terminology is itself problematic given the difference in attitudes between our world and prior ones), most notably in the path-breaking work of Karen B. Stern. However, the existence, much less the significance of wall-writing practices in the Islamicate world has barely been recognized thus far (Stern 2018; Ragazzoli 2018).12 Suffice to say, the practice had deep roots in the Ottoman world, with a genealogy that can be traced back to the antique and late antique milieu examined by Stern in fact, and which, by the eighteenth century, was manifest not just in Eurasia but in European colonies in the Americas as well. By our period, the composition of messages upon publicly accessible and visible surfaces was widespread and widely practiced by elite and non-elite; even lack of literacy need not preclude someone leaving his (and possibly her, though I do not—yet—have such evidence to say for sure) written mark, as this section’s opening story demonstrates. Shrine wall-writing was but one aspect of the wider body of practice, as Ottoman left messages upon the walls of mosques, khans, churches, and other locations, for a range of reasons from simple indication of presence to running arguments with anonymous interlocuters.

Not all shrines received wall-writing, or at least not in equal measure. Our two most important literary witnesses, al-Nābulusī and Evliyā Çelebi, visited a rather staggering number of saints’ shrines in the course of their respective monumental travels through the Ottoman lands, but only in relation to some do they note either the presence of wall-writing or their own contributions. Sometimes records of such wall-writing are incidental: al-Ghazzī mentions that his saintly ancestor al-Nābulusī had written a praise-poem, which he ‘placed’ (either by writing on the wall or on loose paper tacked to the wall or placed directly upon the tomb’s cenotaph) in Ibn ʿArabī’s shrine, a record precipitated by a dream in which a disciple of al-Nābulusī heard Ibn ʿArabī recite the very poem. Had he not recorded the dream account, al-Ghazzī might not have mentioned the poem in the shrine at all. Survival of actual wall-writing is even more contingent: Not only do shrines, as fundamentally ‘living’ structures, require frequent renovations, potentially obscuring many years of wall-writing, with modern shifts in how wall-writing (which gradually became an undifferentiated mass of ‘graffiti’) was perceived, most saints’ shrines saw injunctures against further additions and the erasure or covering up of early modern writing, a shrine like that of Yaḥyā Efendi a fortunate exception.13

Because we are dependent upon such chance survivals and literary references, neither of which are at all systematic, we can only speculate on why some shrines may have been objects of wall-writing devotion and others not. Certainly, popularity, reputation, and existing custom mattered, though alternatively the presence of writing could, if initiated, help sustain a site’s status as a holy place suitable for visitation. One basic factor, which seems obvious, but which proves difficult to parse further in fact, is the matter of substrates: Some surfaces are much better suited for writing than others. The ideal surface, and one which was—and is—indeed typical of many shrines in the Ottoman lands is one of smooth white plaster upon which charcoal, the preferred medium, leaves a very visible, and enduring, trace. Smooth stone (that is, stone surfaces not extensively ornamented or incised) provides the next most ameable substrate, whether in the form of a wall, architectural details, or even a tombstone. Zeynep Yürekli notes the former presence of figural pious graffiti upon the door jambs and voussoirs of the shrines of Hacı Bektāş and Seyyid Gazī, made up of ‘birds, dervish bowls, ships, the sword ẓülfḳār, the hand of Fatima and the curious image of big fish swallowing smaller fish,’ some with evident enough meanings, others quite opaque (Yürekli 2012, pp. 148–49). Such material no doubt once existed in far greater numbers than can now be observered after bouts of well-meaning modern restorations that so often eliminated etchings and writings no longer seen as appropriate. That pious graffiti might be written directly on tombstones is indicated by Evliyā Çelebi, who writes of the recently martyred Shaykh Maḥmūd (here referred to be his other name in common use, Shaykh Rūmī) in Diyarbakır:

- The shaykh lies buried in the Muslim cemetery outside the Rūm gate, in a grave without dome or any structure. May God bless us through this saint’s miraculous powers! This humble author wrote the following lines on his tombstone:

- We came as pilgrims to this station

- Where reposes the great guide, Shaykh Rūmī!

(Evliyâ Çelebi in Diyarbekir, Evliyâ Çelebi 1988, p. 189)

Writing on a shrine’s susbtrates—or on the grave marker of a saint not yet possessed of a shrine—certainly functioned, if implicitly, as an argument for the sanctity of the interred person. Explicating the full range of social work such writing could do, as well as the significance of its reproduction in our narrative sources, could encompass a study in itself. In terms of the intended function of shrine wall-writing, most fundamentally it was for devotees a way of remaining present in the ‘home’ of the saint even after one had physically left. Whether in the form of poetic or scriptural ‘gifts’ to the saint, requests to the saint for his intercession, or simply one’s name and the date of visitation, these personal acts of writing linked the person writing (or dictating, as the case may be) with the saint through a very durable medium. We might think of such writings as a way of holding at length and at distance a conversation with the saint, a continuous expression of love and devotion, whereby the saint’s baraka flowed into the devotee. Once inscribed in a substrate, the writing ‘worked’ without futher interventions, much as talismans written with prophylactic sacred phrases ‘worked’ even without being read or seen. That said, wall writings were also meant to be read by others who came to visit the saint, and in being read, reactivated in a particularly powerful way.14 Through such reactivation by other visitors, wall-writing helped to cement a peripatetic ‘household’ around the saint, devoted to the saint but also devoted, in a different way, to one another, praying for and reactivating the prayers of other visitors.

Shrine-writing could overlap with interventions in more conventional domestic space: al-Nābulusī visited the collective tomb of the al-Bakrī family, a saintly ‘dynasty’ of Cairo through whose lineage familial baraka had been transmitted over the last century, a pattern of particular purchase in Egypt (al-Bakrī 2015; Sabra 2016). Al-Nābulusī and his traveling companions were guests in the home of the current head of the family, Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn al-Bakrī (al-Nābulusī 1998, p. 31), and after visiting the family shrine wherein the ‘lords of the Bakriyya’ were entombed, al-Nābulusī composed a qaṣīda (a form of poetry often used for eulogistic purposes) in praise of the maqāmāt (that is, spiritual stations) of these holy dead. Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn had this qaṣīda inscribed on a wooden board and hung up inside the shrine, a contribution that lay in-between more permanent, ‘architectural’ inscriptions and the sort of wall-writing we have discussed so far. Here as elsewhere the categories and terms to which we in the modern world are accustomed generally lack the ideal capacity for encompassing the many possible forms these written interventions took (al-Nābulusī 1998, p. 64).15 It is also a challenge for us to appreciate the presence and power written words could take in a pre-typographic world in which public texts, even when monumental inscriptions are taken into account, were considerably rarer than in our text-saturated present. The social work al-Nābulusī’s act of writing and Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn’s space-modification facilitated was also complex. Al-Nābulusī contributed to the veneration of the ‘lords of the Bakriyya’ by inscribing their sainthood in poetry, while also reinforcing his bonds with the family and offering a sort of repayment for Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn’s copious hospitality. Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn benefited, too, from the ‘endorsement’ of an important and himself widely venerated shaykh while further strengthening the bonds of friendship and mutual support between himself and al-Nābulusī by rendering the shaykh’s qaṣīda into a format more durable than ordinary shrine wall-writing.

In these ways and more, shrine wall-writing, then, can be understood as a means by which the domestic aspect of the saint’s shrine was (further) constituted, as an intimate space of communication with the spirit of the saint and with his or her ‘family’ of devotees, present and future. The logic of this particular form of wall-writing followed upon the domestic logic of the shrine: As the saint’s home, the devotee offered a gift to the saint and his household, a gift that also anchored his continuing presence in the vicinity of the saint. To etch an inscription on the wall or other surface of a saint’s ‘house’ was in some ways to go beyond one’ status as visitor and to instead become a sort of household inhabitant, the written traces of one’s name and supplications and poetic composition abiding opposite a beloved saint, seen and read by the steady stream of other guests of the holy person entombed there.

4. Finding the Prophet in Domestic Space: Envisioning the Effects of Devotion to Muḥammad

If a range of practices, attitudes, and imaginations worked to locate the domestic upon and within the tomb of the saint, in the homes of the living, a related if distinct set of practices, material objects, and ritual texts brought holy presences into already existing domestic space and offered routes towards transformations of that space. While diverse saintly presences and relationships were reproduced and maintained in domestic settings, as displayed in the seventeenth century correspondences of ʿAsiye Hatūn (Asiye Hatūn 1994), of greatest importance was devotion to the Prophet Muḥammad. What follows will consider further two aspects of this interplay of the domestic and of the transformation of the domestic: First, a look at how taṣliya, whether aurally performed using the Dalā’il al-khayrāt or some other means, was envisioned as introducing the Muḥammadan presence into one’s home and so in a way transcending the constraints of the domestic while transforming that very space. Second, I will briefly trace the history of the images of holy places and objects that became a central part of the Dalā’il as a material object. I will demonstrate, among other things, both a ‘domestication’ of a previously ‘public,’ communally experienced visual repertoire and the place of these images in generating the Muḥammadan presence within the walls of one’s own home.

That the Dalā’il al-khayrāt and similar repositories of devotion to Muḥammad were regarded, indeed valorized, as domestically oriented bodies of practice is evident from the commentary literature and other sources; the abundance of the many extant manuscripts and the evidence of frequent use on their pages argues that such literary observations and prescriptions in fact corresponded to actual practice. Initial forays into reconstructing the ownership and use histories of individual copies of the Dalā’il and other devotional works (with multi-volume or multi-excerpt compilations also very frequent) have established ownership of the text by both institutions and households. There is still need however to better establish the details of who owned copies of the this text and what those copies would have looked like (certainly, ‘prestige’ copies with full illuminative and sophisticated illustrative schemes are over-represented in most modern institutional collections) (Hanna 2003; Göloğlu 2018, pp. 231–35). My goal here is more modest: To briefly demonstrate how certain Ottoman authors envisioned Muḥammadan devotion in certain modes as being uniquely domestic in nature.

We begin with the hagiography of the Dalā’il al-khayrāt’s compiler, Muḥammad al-Jazūlī (d. 1465), venerated as a saint in both his native Maghrib and everywhere the Dalā’il went, a status reinforced in hagiographic compositions as well as in the commentary (sharḥ) literature on the Dalā’il (Cornell 1998; Blecher 2013). Arabic-language treatments of the saint give, in varying lengths, a now classic story that explains why al-Jazūlī compiled the book. One day, while trying to retrieve water from a well in order to perform his ritual ablutions, he was stymied by the lack of a rope. A girl came along, breathed into the well, and up came the water of its own accord! Amazed, al-Jazūlī asked her what in her practice of piety had invested her with such miraculous ability, to which she replied it was her regular practice of invoking peace and blessings upon the Prophet Muḥammad. Inspired, al-Jazūlī set out to compile his now classic work (al-Fāsī 1989, pp. 6–7). In his early eighteenth-century Ottoman Turkish commentary on the Dalā’il, the otherwise obscure preacher and exegete Qara Dāvudzāde Meḥmed Efendi (d. 1756) elaborated upon this story further.16 The ‘girl’ (kız) expresses amazement that someone whom ‘the people praise for your goodness and miracles (kerāmāt)’ is unable to draw up the water. In this version, al-Jazūlī goes home determined to transform his devotional life, a determination reinforced when that night he awakes to see his wife quietly arising from bed and heading outside. Angered and jealous, he creeps off after her, and is amazed to see her go down to the seashore, encounter two wild lions, mount one, and ride him across the water to an island where she performs the ritual prayer. Upon her return, he asks her what she has done that has given her such powers, to which she replies, unsurprisingly, that it is her practice of pronouncing peace and blessings upon Muḥammad (Qara Dāvudzāde 1750, pp. 2–3).

There are many potential messages encoded in these accounts (and in other stories in Qara Dāvudzāde’s compendium emphasizing the superiority of a woman’s piety and practice over that of a man). Central is the idea that not only can women practice devotion to Muḥammad within the space of the home (and without), but that they are potentially especially powerful practicioners of this devotion, devotion whose effects might well transcend those of other more male-dominated forms of saintliness. Furthermore, if the sanctification of women’s domestic lives and spaces (and those of men, who are meant in these and similar accounts to look to women for emulation) are encouraged in these accounts, the transcendence of the domestic is also implicitly suggested: While, we surmise, al-Jazūlī’s wife practiced her devotion to Muḥammad primarily within the house, the connection with God and his Prophet that she thereby generated and which endowed her with saintly powers enabled her to not only depart from the boundaries of the house, but even walk upon water and command wild beasts. She was quite literally transported beyond the bounds of the household through her devotion to the Prophet. Perhaps even more remarkably, there is no indication in Qara Dāvudzāde’s story that she was in any way at fault in neither informing her husband of her devotional regime nor in not asking his permission to leave the house and go out walking on water and cavorting with lions.17 There is an implicit message in these stories that devotion to Muḥammad is not just accessible to women in some form or another, but that it is especially suited to opening up the spiritual and otherwise horizons of women. While the women in the two above stories are shown literally transcending the limits of the domestic, implicit is the idea that even while centered on the house, within the space of the domestic, women can partake of a vigorous and powerful devotional regime, such that they might even surpass the powers of a prominent saint.

However, while it might be tempting to interpret these bodies of devotion as being uniquely gendered as ‘female,’ perhaps as extensions of the ‘female space’ of the household, other instances from the commentary literature suggest a more complex picture. Three examples from the commentary (sharḥ) of the most influential and most widely copied commentator on the text in Arabic, Muḥammad al-Mahdī ibn Aḥmad al-Fāsī (d. 1698), provide a good sense of other iterations of the domestic setting prescriptive literature suggested as normative for devotion (Dennerlein 2018). In a short story in his manāqib of al-Jazūlī, for instance, al-Fāsī relates the tale of a student in Fes who owned the Dalā’il and another, somewhat similar, compilation of blessings and prayers upon Muḥammad, the Tanbīh al-anām, copies of which circulated in the Maghrib and in the Ottoman world thought not, it would seem, beyond. In the story, the student would leave his copy of the Dalā’il underneath the Tanbīh then leave his room in the madrasa. When he returned, the Dalā’il would have miraculously switched spots with the Tanbīh, coming out, quite literally, on top (al-Fāsī 1989, pp. 9–10)! Beyond the obivious purpose of this story in establishing the superiority of one form of Muḥammadan devotion to another, the account points to domestic space—here, a student’s private room—as the expected physical location devotional books would be used and stored. Such a domestic context is implied even more strongly in two stories of the effects of taṣliya al-Fāsī provides in his commentary on the Dalā’il, stories that also point to the potential transformative effects of such devotions upon the spaces in which they were practiced. The first story concerns a pious craftsman—as with Qara Dāvudzāde, the emphasis is upon the broad accessibility of this devotional regime to people up and down the social ladder—who reported,

I used to perform every night by myself before going to bed a certain number of salutations and blessings upon the Prophet, God bless him and give him peace. One night I had completed this number of prayers and feel asleep. I was then dwelling in a first-floor room (ghurfa). Suddenly the Prophet, God bless him and give him peace, entered into the door of the upper room, light streaming from him. He stood up before me and said, “What is this sorrow which increases ṣalāt upon me?”18 Then I was embarrased to kiss him on his mouth, so I turned my face and he kissed me on my cheek. Then I awoke with a start in that very moment, awakening my wife beside me. The house (al-bayt) was suffused with the smell of musk from his scent, God bless him and give him peace, and the scent of musk remained on my cheek some eight days, my wife finding it upon my cheek every day and night!(Maṭāliʿ al-masarrāt, 58)

The setting here is not only determinedly domestic, it is strikingly intimate, both in the space in which it unfolds—an ‘upper room,’ in which the man and his wife sleep and to which others would presumably not have access, itself a part of a larger domestic complex, the bayt—and in its particular details. An almost erotic charge pervades these details, the performance of devotion to the Prophet establishing a means for him to penetrate into inner domestic space and leave his trace therein, both upon the body of the devotee and upon the space itself. The scent of him pervades the house, the physical, sensory (and indeed sensual) effect of the devotions performed within.

This sensory, even sensual effect of taṣliya within the walls of the house is further reinforced in the next story al-Fāsī relates, set in late medieval al-Andalūs, and related by one Abū al-Qāsim al-Murīd:

Lest there be any doubt as to just whose scent the smell of musk is in this story, just before this passage al-Fāsī relates how the scent of Muḥammad is directly derived from the smells of the Garden itself, a scent that he in turn bestows upon those who practice devotion to him. Through the potency of taṣliya—of which the Dalā’il is presented as the finest and most accessible distillation—ordinary domestic spaces can be suffused with the scent of Paradise. Domestic space becomes marked in this rendering with the space of the eternal Garden through the presence of the Prophet breaking into that inner, intimate space of the house, opening it to himself and to the eternal.When Shaykh Abū ʿUmrān al-Barda’ī came to Malaga he found therein Shaykh Abū ʿAlī, that is al-Kharrāz [‘the Cobbler’]. The three of us met together one day in my home (dārī) for food I had made for them… My father was also present, and he had come down with a cold such that his sense of smell was interrupted. Shaykh Abū ʿUmrān said to Shaykh Abū ʿAlī, “Yā Abū ʿAlī, you have eight years [of devotional performance], so what effect has taṣliya had on you?” He replied, “Yā Sīdī, it has endowed me with such-and-such [spiritual powers].” Shaykh Abū ʿUmrān replied, “This is what is manifest to children; one ought not in such manner practice remembrance of the Prophet.” Then he said, “Breath upon the palm of the hand of Shaykh Abū al-Qāsim’s father.” He did so, and the smell of musk wafted about, but weakly. Then Shaykh Abū ʿUmrān blew upon my father’s palm, and by God! The smell of the musk cleaved my father’s nostrils to the point that they started to bleed from the force of it! Blood flowed from his nose and the scent pervaded my home until scents of musk reached even the neighbors!(Maṭāliʿ al-masarrāt, 59)

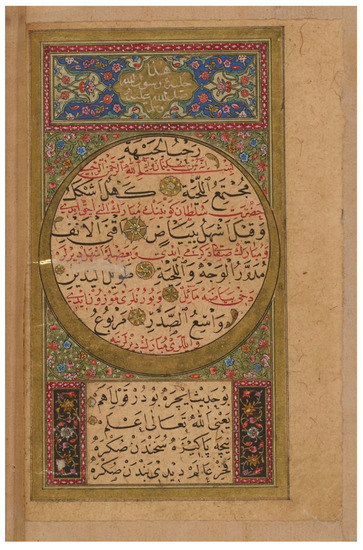

5. Bringing the Holy Home: Devotional Imagery in the Dalā’il and Other Contexts

Both al-Fāsī and Qara Dāvudzāde largely limit themselves to the aural performance of devotion to Muḥammad, following the text of the Dalā’il itself in this regard. However, within the original late medieval composition of al-Jazūlī itself is the seed of a tacticle and visual regime of practice that would flourish in the early modern Ottoman world (and beyond), and in so doing establish another means of drawing the Muḥammadan presence into domestic space through participation in the most important shared holy places of the Muslim umma, those of Mecca and Medina. These images, along with related pictoral depictions of objects associated with Muḥammad, emerged in the medieval period but were either limited to elite audiences or were accessible to others through public display in communal locations such as mosques. It would be primarily through the medium of the Dalā’il and its visual repertoire that images of Mecca and Medina, along with new forms of visual representation of the Prophet’s presence, would become domestically accessible. Simultaneously, the ways in which devotees interacted with such images would diversify and shift, from the tactile to more visual and imaginative modes of participation, the originally Ottoman ḥilye an important aspect and driver of this change. While the Turkish-speaking provinces would see the most expansive elaboration of devotional imagery, these transformations would play out in the Arabic-speaking regions as well and beyond the empire’s borders both west and east. This final section will trace the trajectories of these devotional images from settings of a primarily communal and public nature to an increasing emphasis on intimate, domestically rooted use, drawing upon both material evidence and that of commentaries and devotional texts themselves.

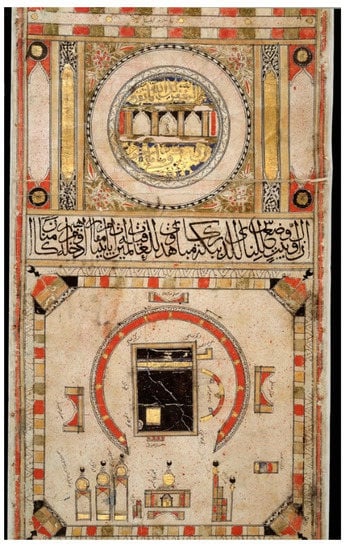

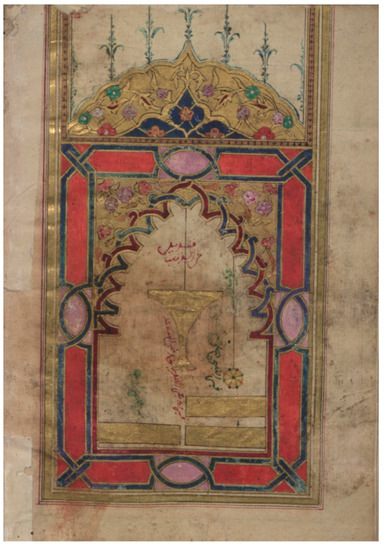

The fully elaborated repertoire of devotional images that would become typical in copies of the Dalā’il in (primarily) the Turkish-speaking half of the Ottoman Empire had multiple points of origin, each displaying a movement from the communal to the domestic.19 Within the text of the Dalā’il itself is a short description of the most significant physical site associated with Muḥammad—the so-called Rawḍa (literally, ‘Garden’) of Muḥammad, the place in which he and Abū Bakr and ‘Umar, the first two caliphs, were buried. The text itself envisions a clarifying diagram of the three tombs, al-Jazūlī himself probably having drawn the original prototype, which was soon elaborated somewhat with additional details, a facing image of the nearby Muḥammad’s Minbar complementing that of the Rawḍa (see Figure 6 for an Ottoman Syrian example). In North Africa and some other regions, these two images, rendered in many different styles, would often constitute the only imagery. Copies made in the Arabic-speaking provinces of the empire tended to follow this pattern, though not exclusively. The presence of these two schematics—anchored in the text itself—served as an entry point for further elaborations, though the exact chronology and rationales are murky; the following is only a brief summary of the likely trajectory and of the possible interpretations we may attach to that trajectory (Rusli et al. 2016; my analysis departs somewhat from that of Witkam 2007).

Figure 6.

A fairly typical representative of the ‘traditional’ pairing of depictions of the Rawḍa with Muḥammad’s Minbar with decorative elaboration typical of the wider Ottoman world, from an Ottoman Syrian copy of the Dalā’il completed at some point in the eighteenth century. University Library of Leipzig, Vollers 200.

Images of Mecca and Medina as a whole and of sites within or associated with the holy cities (including Muhammad’s Minbar and the Rawḍa) long predated the composition of the Dalā’il and continued to be elaborated upon in other media and matrices as well long after the elaboration and spread of the Dalā’il and its images. Views of Mecca and Medina were developed and propagated in, among other contexts, pilgrimage certificates, often elaborate works in scroll-form that documented someone’s pilgrimage to Mecca (Chekhab-Abudaya et al. 2016). While a surprising number of these otherwise rather ephemeral texts, most seemingly produced in Mecca, have survived, dating from the thirteenth century forward, their social contexts are not always obvious (Aksoy and Milstein 2000). Some show signs of having been hung up, either in full or cut down into constitutive components. We are fortunate to possess a passage from the early sixteenth century that sheds more light on the context in which these images were displayed and could have entered into wider artistic and devotional consciousness as a result. In his treatise on the proper usage of sacred spaces, the sufi scholar Shaykh ʿAlwān of Hama (d. 1530) described what he saw as pernicious contemporary practices of mosque ‘ornamentation (zukhruf)’ that needed to be confronted (Ibn Aṭīyah 2003, pp. 27–28; Allen 2019b, pp. 116–38). Among the ‘reprehensible practices’ of the people of Syria in mosques, Shaykh ʿAlwān argues, is that

they raise up sheets of paper joined together decorated with the image of the noble and exalted Ka’ba, the noble Stone, and other than that, on which they write things such as, after praise to God and what follows it, ‘So-and-so made the ʿumra 20 on behalf of so-and-so,’ and ’So-and-so made the ḥajj on behalf of so-and-so.’ They intend thereby—and God knows best—fame, eye-service, and repute, and the dissimulation of the repute of the one for whom the ʿumra or ḥajj was made, in life and in death. They attach those to the qibla [wall or niche or both] of the mosque and elsewhere on its surfaces, causing distraction on the part of those praying the ṣalāt through looking at the decoration.(Asná al-maqāṣid, pp. 28–29)

While we need not accept at face value Shaykh ʿAlwān’s interpretation of the moral probity of people who so displayed pilgrimage scroll imagery, his supposition that they served as sources of social capital does not seem far off. These scrolls were meant to be seen, displayed in a communal setting (consider the example at Figure 7). The iconography developed primarily in these scrolls—which included both schematic views of Mecca and Medina as well as of other holy places and of iconic ‘relics’ such as Muḥammad’s sandal-print—would go in many directions from their original contexts. In the Ottoman world, the public display of images of Mecca and Medina would find more permanent form in, above all, the many Iznik tile panels presenting somewhat similar schematic depictions of either one or both holy cities of the Ḥijāz (see Figure 8 for an example), prominently if somewhat incongruously displayed on the qibla walls of Ottoman mosques great and small. Such images worked to link the space of the mosque to that of the Ḥijāz and invited the viewer to imaginatively traverse the sacred topography him or herself (Maury 2013). Relatedly, depictions of the iconic ‘relics’ of Muḥammad, particularly his sandal or foot-print, entered tile form, across the Ottoman world and not just in the Turcophone (Milstein 2006).21 While there is at least one instance of tilework depictions in a domestic context, it is the highly rarified one of the Topkapı’s Harem. More important for our purposes, images of the holy places of the Ḥijāz would also begin to appear within the pages of books, most significantly the Dalā’il.22 This shift would begin the movement of these devotional images from shared communal settings to also existing within domestic, household ones—which, in this case, entailed a movement from spaces in which women’s participation was secondary and restricted (that of the mosque) to spaces in which women were dominant presences (that of the home).

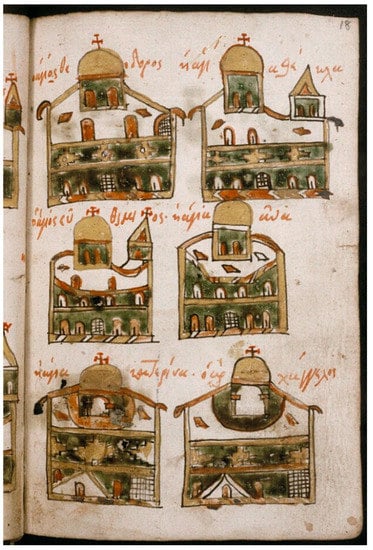

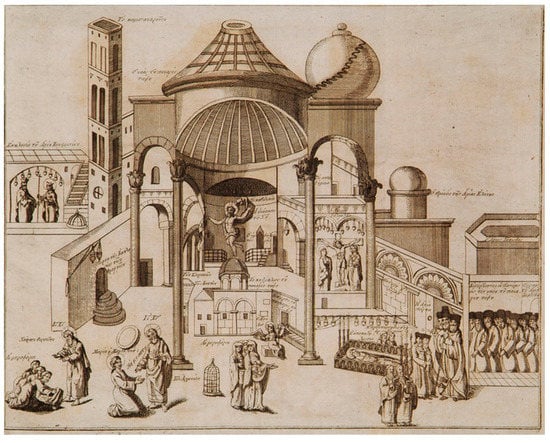

Figure 7.

A section of a pilgrimage scroll showing examples of schematic depictions of holy places in the Ḥijāz; the entirety or portions of such scrolls would have been mounted on mosque walls for public display, a function that may well have been in the makers’ minds given the scale of the depictions. This example was completed around the year 1433 and displays the increasingly sophisticated visual repertoire that developed within the genre. British Library, Add. MS 27566.

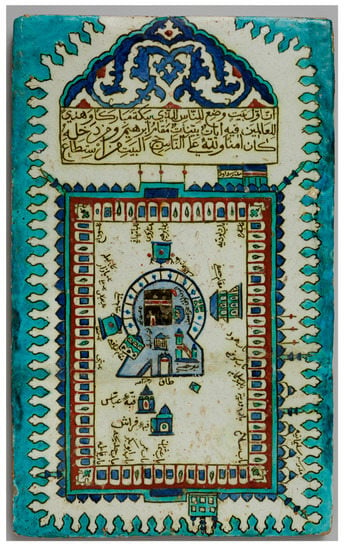

Figure 8.

A circa 1640 tile depiction of Mecca with the Ka’ba at the center, formerly set in the qibla wall of a mosque. The relationship between the tile’s visual vocabulary and that of the pilgrimage scroll is immediately evident. Aga Khan Museum, AKM58.

By at least the mid-seventeenth century, copies of the Dalā’il itself frequently included depictions of the two holy cities—either complementing or supplanting the original views of the Rawḍa and the Prophet’s Minbar—with some stylistic departures from the original schematic renderings found in the pilgrimage scrolls, as is visible in one of the earliest copies of the text, produced in early seventeenth century Tunisia (probably).23 Around the start of the eighteenth century, the depictions of Mecca and Medina would increasingly (though far from exclusively) be rendered in a cavalier perspective (Figure 9) redolent of contemporary Western European art, a change primarily found in the northern, Turcophonic tier of the empire (Maury 2010), though further research will no doubt establish the exact regional makeup of this change. The ensuing visual repertoire of the Dalā’il would increasingly shape the imagery of other devotional texts. For instance, the previously cited manuscript of Qara Dāvudzāde’s commentary on the Dalā’il reproduces, as a sort of establishing citation, a Dalā’il-style cavalier perspective view of Mecca in the opening illuminated frontspiece (Figure 9; see also Figure 10). Many other similar cases could be cited.24

Figure 9.

A miniature rendering of Medina surmounts the ‘unwān (illustrated headspiece) at the beginning of this Ottoman Turkish translation and expansion of al-Fāsī’s commentary on the Dalā’il. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan, Special Collections Library, Isl. Ms. 672, fol.1a.

Figure 10.

This Ḥāfiz ‘Osmān ḥilye received in the mid-eighteenth century an illumined headpiece with an image of Mecca, and, at some point in the nineteenth, the green-and-gold border; signs of considerable use and display and ensuing re-mountings are evident across the piece. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan, Special Collections Library, Isl. Ms. 238.

Another major source of the Dalā’il’s iconographic repertoire, at least in the core provinces, was the early modern transformation of long-existing physical descriptions of Muḥammad (and, to a lesser degree, other holy persons from early Islam), the shamā’il and ḥilya (Ottoman Turkish ḥilye) literature, into a discrete genre of texts and objects (Elias 2012, pp. 272–74; Gruber 2014; Gruber 2019, pp. 285–381). Most famously, these descriptions, which could be traced back to canonical hadith literature, formed the core of the aforementioned calligraphic ‘icon’ known as the ḥilye-i şerīf (for examples see Figure 3 and Figure 10). Not only were ḥilyes increasingly included in (primarily) Turcophonic copies of the Dalā’il, the modes of engagement associated with them, focusing on the visual, imaginative, and prophylactic, seem to have contributed to the changes in how Ottoman Muslims interacted with the imagery of the Dalā’il and related texts.

Unlike medieval images of Mecca and Medina or the iconic depictions of the ‘relics’ of Muḥammad, the ḥilye appears to have been geared towards domestic contexts from the beginning, reflective of the inceasingly domestic context of devotion to Muḥammad by the end of the seventeenth century. The following ‘hadith’ (it is almost certainly an early modern pious fabrication), taken from a mostly Turkish book-form compilation on the Prophet’s physical characteristics (Dervīş Ibrahīm 1716/17), suggests both the domestic context and the perceived power of these texts:

The domestic context is foregrounded here: The ḥilye protects one’s house (whatever sort of house it may be) simply by being there. Like the aural performance of taṣliya, it is offered as a means of replicating Muḥammad’s powerful presence within the walls of one’s homes, of opening out domestic space to the eternal presence of the Prophet. Like other examples from the broader genre, this text offers multiple routes to ‘activation’ of its powers. Whether in textual form such as that in which the above hadith was embedded, or in the calligraphic ‘textual icons’ popular from the late seventeenth century forward, which could be displayed on one’s wall, the ḥilye acted as a prophylactic for one’s home, regardless of whether anyone was looking at it, reading it, or handling it.25There is none who writes out this my [Muḥammad’s] description, then arranges (yaṣnaʿuhā) it within their house (dār) except that Satan will not draw near their house (bayt), nor will oppressive power, trial, nor pestilence strike that house, nor will sickness, pain, the envy of an envious person, the magic of a magician, flood, fire, theft, feebleness, nor misfortune. And no worry, sadness, nor anxiety will afflict them, so long as this blessed, beneficious description is in that place (manzil), house, or palace (qaṣr) wherein they dwell. And whoever recites it or listens to it, it is for them the proof and profound reliance which the Prophet, peace and blessings be upon him, vouchsafes.(Ḥilye-ye Şerīf, pp. 8–12)

The fact that many Arabic-language descriptions of Muḥammad were not simply reproduced in Arabic but were also the object of Ottoman Turkish translations, sometimes in a decidedly vernacularizing register, points to a related means whereby these descriptions could activate the Prophetic presence, namely, through the (properly guided) imagination. Closely akin to the practices of ‘fixing’ the image of one’s shaykh in one’s heart and thereby establishing an effective spiritual ‘link’ with him from afar, practices developed by, but not limited, to the Naqshbandī sufi ṭarīqa, descriptions of the Propeht could enable one to ‘see’ Muḥammad by means of the heart (Allen 2019b, pp. 432–34). The reader (or listener) could form his or her own image of the Prophet, which might in turn aid in summoning Muḥammad’s visit through the medium of the dream-vision. The overlap with the role of taṣliya, as disussed above, in summoning the Prophet’s presence is obvious enough. Unsurprisingly, by mid-eighteenth century, if not before, descriptions of Muḥammad, including entire calligraphic ḥilyes, had entered into the Dalā’il’s iconographic repertoire (see Figure 3 for an example) alongside the by then ‘canonical’ sets of image; at the same time, ‘freestanding’ ḥilyes themselves also often took on aspects of the Dalā’il’s visual scheme, such as the eighteenth century versions printed using brass matrices, a form of the device that would have been particularly suited to domestic use up and down the social ladder (Perk 2010, pp. 36–37).26

The devotional images of the Dalā’il—from those of the Rawḍa to the full-fledged depictions of Mecca and Medina to embedded ḥilyes—elicited responses that ranged from the highly tactile to the visual and imaginative. Particularly when placed within the pages of books, these devotional images invited physical, bodily reponses. Reading the written labels (indicating names of mosque and tomb structures, gates, and various other significant sites) of these depictions and imaginatively engaging with them required, as Sabiha Göloğlu has noted, no small degree of bodily interaction simply by virtue of either turning the manuscript or turning one’s self in order to literally read the writing and to follow the layout of the image (Göloğlu 2018, pp. 151–56). Most significantly, as Christiane Gruber has discussed in detail, both representational and more abstract depictions of Muḥammad were for many early modern Muslims, Ottoman and otherwise, objects of tactile devotion, as they rubbed, kissed, even scraped off paper and pigment as means of activing the baraka contained therein (Gruber 2010; Gruber 2019, pp. 269–85). Yet, while in the neighboring Maghrib the images within the Dalā’il were frequently objects of tactile veneration all through our period, as clearly visible in Figure 11, relatively few Ottoman Dalā’ils show such signs of intense tactile engagement. Significantly, neither do early modern ḥilyes, whether of the free-standing, wall-mounted sort or of those included in devotional books such as the Dalā’il.27 Instead, the emphasis appears to have been upon the visual and imagination-facilitating aspect of these images, their power unlocked primarily through the devotee’s gaze. Even as tactile forms of veneration and engagment remained popular in other contexts, in the core Ottoman lands, the images of the Dalā’il became primarily objects of visual and imaginative engagement.

Figure 11.

A probably eighteenth century depiction of the Rawḍa, from a Maghribi manuscript copy of the Dalā’il, demonstrating the highly schematized style that remained popular in North Africa—here reduced to almost pure geometric abstraction—alongside evidence of extensive tactile veneration, all contained within a framing that combines long-standing Maghribi motifs with a headpiece and floral fill highly typical of Ottoman manuscript illumination. University Library of Leipzig, Cod. Arab. 114.

Our commentator al-Fāsī provides a good picture of such overlapping layers of meaning and use these various images could receive as well as the transformations of the early modern period. While himself resident in the Maghrib, al-Fāsī drew upon opinions—concerning the Dalā’il and other, related matters—which he found in writings by (usually anonymous) ‘Easterners’ (mashāriqa), that is, inhabitants of the Ottoman Arabic-speaking provinces. His discussion of the purpose of the imagery in the Dalā’il begins with a citation from the Mamluk jurist Tāj al-Dīn al-Fākihānī (d. 1331) who, despite his opposition to the emergent practice of mawlid festivities (Katz 2007, pp. 70–71), wrote approvingly that ‘one who cannot make pious visitation to the Rawḍa [itself] may go and piously visit the likeness (mithāl) [thereof], witnessing it with desire and kissing it so that love and desire increase in him’ (al-Fāsī 1865; Göloğlu 2018, pp. 267–68). He gives as his example, not an image of the tomb itself as we might expect, but the image of Muḥammad’s sandal-print, one of the oldest such devotional images (Gruber 2019, pp. 276–85).

In the passage cited from al-Fākihānī, reflecting late medieval devotional culture before the Dalā’il, two major differences stand out: One, devotees are envisioned going to visit a pious image, the verb used normally referring to pious visitation to a tomb or other holy place. The imagery is public. Second, the primary mode of participation the passage suggest is the tactile, not the visual and imaginative, which are decidedly secondary. By contrast to the late medieval context visible in the Mamluk jurist’s words, the proliferation of the Dalā’il and related texts and objects meant that for many early modern Muslims, no special trip was necessary: Devotional imagery could be brought into one’s home. While bodily engagement remained a part of Ottoman devotional repertoires, the visual and imaginative emerged as just as, if not more, important, at least in the context of images of the holy places of the Ḥijāz. Al-Fāsī goes on to provide his own explanation for why images are included in the Dalā’il: First, he notes that the Dalā’il acts as compendium uniting all the various ways Muslims had sought to describe Muḥammad, from sīra literature to accounts of his miracles to descriptions of his physical characteristics (shamā’il). Depicting his tomb—and by extension, other places closely associated with his life—‘is among the things connected with that.’

Al-Fāsī goes on to discuss, drawing upon anonymous contemporaries (in all probability from the Ottoman world) the practice of imaginatively summoning up the image of Muḥammad himself. The devotee should picture ‘before his eyes’ Muḥammad in his humanity, clothed in divine light, so that the devotee can ‘stamp his image, God bless him and give him peace, within his spiritual self (rūḥānīya) and become intimately acquainted with [that image],’ to great spiritual benefit. In order to strengthen this practice, one might also picture one’s self gazing at Muḥammad while sitting—in one’s mental picturing—before ‘his blessed tomb,’ an image that the devotee can keep constantly before himself and which will spur him to greater commitment and contact with the Prophet. However, what if the devotee has never been to Medina and does not know what the Rawḍa and Muḥammad’s tomb looks like? Then, he can gaze upon the images within the Dalā’il, al-Fāsī writes, and having familiarized himself with them use them in his practice of visualization. Such images are especially useful for the ‘commonality.’ However, citing an anonymous ‘Easterner,’ al-Fāsī also notes that these images can be rendered in gold leaf and brilliant colors as a way of honoring Muḥammad and of strengthening visualization practices, a likely reference to the proliferating diversity and complexity of images in the Ottoman world from the seventeenth century forward (al-Fāsī 1865, pp. 137–38).

Here, the stress is on the individual viewer using the images as mental templates for constructing, as it were, the topographic ground for encountering Muḥammad, transforming the inner ‘space’ of one’s heart into the sacred space of Mecca and Medina, their significance here having less to do with their role in the ḥajj and more to do with their connections with Muḥammad. If tactile responses were invited by the correspondence of the image on the page (or other medium) with prototype, here the correspondence was of image in the mind and heart with the prototype, the image on the page a means of forming that inner image. Not unlike the role that descriptions and images of Jerusalem could play for medieval and early modern Christians (East and West) in their devotions to Christ, the imaginative landscape of the holy cities mattered most because it facilitated personal desire and encounter (Mecham 2005). All of this devotional practice could take place as easily within the confines of one’s home as anywhere else, even in Mecca and Medina themselves, with devotional images providing a potent and, al-Fāsī stresses, widely accessible means of doing so. In his slightly later Ottoman Turkish commentary, Qara Dāvudzāde’s explanation tracks largely alongside that of al-Fāsī, though he focuses entirely on the visual and imaginative, as we might expect based on the physical evidence from the Ottoman world. The images of the holy places stir up desire for Muḥammad, he writes, for those who cannot visit the holy places in person but who can gaze upon their representations. By bringing the distant holy places home these images provided the potent topography of encounter with the Prophet to men and women for whom physical pilgrimage was not a possibility (Qara Dāvudzāde 1750, pp. 241–42; Göloğlu 2018, p. 269). The holy places provide yet another means of facilitating Muḥammad’s presence for ordinary believers, men and women alike.

6. Conclusions: Recapitulation and Considering Points of Connectivity

Looking back over our vista of Ottoman devotional life as it intersected with different iterations of the domestic, it will be helpful to reconsider the linkages between the two realms covered, that of the saint’s shrine and of household devotion to Muḥammad. First, one striking commonality that I have touched on only in passing is the degree to which both the ‘domesticated’ space of the shrine and the temporary space of devotion in the domestic household were both accessible, with something like rough equality, to men and women. While our analysis of the space of the shrine only touched on gendered aspects, the free movement of women in and out of shrines, often in conditions of unsegregated mixing, was noted by critics and supporters alike. Not only did this sort of gender mixing heighten the domestic aspect of the shrine in its function as the home of the saint, we may speculate that Ottoman observers themselves may have made sense of such mingling as permitted by the unique nature of the physical vicinity of the saint. In the case of devotion to Muḥammad, the importance of women as devotees alongside men is laid out explicitly in the prescriptive literature, with the implication that the kind of devotion represented by the Dalā’il al-khayrāt did not require special, communal space but was as easily carried out at home as anywhere else. Such accessibility was not limited to spatial requirements. The ritual material of devotion to Muḥammad included much that could be easily memorized, even for those lacking literacy, while the imagery associated with the Dalā’il did not require literacy at all, only some awareness of what was depicted and what one ought to ‘do’ with that imagery. Also, where the images of the holy places (and things) of the Ḥijāz, of the ‘relics’ of Muḥammad, and the written descriptions of the Prophet’s characterstics had in earlier periods been of much more limited and restricted access, early modern transformations permitted their introduction into household settings and hence at least potentially for women’s use. In neither the shrine nor in domestic devotion did ‘domesticity’ preclude the participation of men, nor ought we to see either as being gendered ‘feminine’ as opposed to ‘masculine.’