1. Introduction

It was evening in Teck Whye, at the Choa Chu Kang Dou Mu Gong (CCKDMG [蔡厝港斗母宫]), as I watched Ah Q, one of the temple’s longtime caretakers, gingerly carry out three sets of giant joss sticks to the entrance and light them up. It had become my daily habit to observe him replacing burnt joss sticks with new ones. Bearing colorful dragon patterns at a height of two meters, these joss sticks are a sight to behold (see

Figure 1). During the Nine Emperor Gods Festival, devotees offer these joss sticks to “report one’s filial piety” (

baoxiao [报孝]) to the Nine Emperor Gods.

Since 1998, the National Environment Agency has limited the number of giant joss sticks the temple can burn to three sets of three per day, citing the risk of environmental pollution. Ah Q belligerently declared that, without this limit, the number of joss sticks they burn would “end up lining the entire street.” During the kampong era, the joss sticks were “so huge that cranes were needed to put them up,” and they burned for days. “But now,” he continued, “we can only burn joss sticks up to two meters in height.” Finishing the task, he paused and then whispered, “The government doesn’t like Chinese religion; that’s why we have so many restrictions.” As I later learnt, this sudden complaint reveals the tip of the iceberg that is the uneasy relationship between the CCKDMG and the Singaporean state during the annual festival.

I argue that, in the Nine Emperor Gods Festival, the ritualistic orchestrations of the sovereignty of the Nine Emperor Gods construct physical manifestations of the larger cosmological order governed by the nine divinities. The festival overturns the state’s functionalist meaning of space in favor of ascribing sacred meanings to ritual locations, performing a divine bureaucratic order to which devotees and state bodies are beholden. Spatial negotiations between the gods, the state, and the temple’s administrative committee (

lishi [理事]) before and during the festival reflect how they all co-participate in the same complex society known as an inclusive “cosmic polity” (

Sahlins 2017). This inclusive “cosmic polity” exists as an ontological reality for the temple’s ritual practitioners and devotees, who encounter the contestations between divinities and the secular state during the festival’s planning and execution. The agency of the nine divinities is most potently instaurated—in Latourian terms—and actualized when they emerge as agents that ward off misfortune and bring blessings during the festival.

1 By reclaiming the urban spaces where the festival’s rituals are carried out, these articulations of divine sovereignty serve as a fertile ground upon which the bureaucratic power of the Nine Emperor Gods is reproduced, fashioning devotees into imperial subjects and challenging state-imposed imaginations of space.

The festival’s spatial enactments of Singapore’s landscapes as territories under the divine governance of the Nine Emperor Gods subject devotees, practitioners, and to a certain extent, the Singaporean state, under divine sovereignty. While the gods renew their annual blessings to devotees, the devotees are simultaneously renewing their allegiances to the Nine Emperor Gods. While agency is commonly understood by devotees to be human-centric and state-defined, the gods’ presences expand such understandings into the larger cosmological order, where agency also manifests in the form of divine sanctions. Ultimately, the festival reveals the authoritarian ethos of the Nine Emperor Gods who, although enacting an imperial order dissimilar from the state’s bureaucracy, allow devotees to recognize the fundamental limits of their personal agencies and lack of power over their lives. Yet one must first ask: who are the Nine Emperor Gods? And what is the Nine Emperor Gods Festival?

The Nine Emperor Gods are a pantheon of possessing deities unique to Southeast Asia. Some say that they are the nine star-deities who reign over the planets in the solar system, while others believe them to be nine heroes who appeared at the end of the Qing Dynasty (

Cheu 1988). The cult originated in Fujian, China, before proliferating to Southeast Asia in the late 19th century. Held from the first to the ninth day of the ninth lunar month, the Nine Emperor Gods Festival celebrates the divine supremacy of the Nine Emperor Gods. In 1910, a Chinese businessman named Choo Kee introduced the festival to Singapore (

Heinze 1981, p. 155).

Scholars have established that the Nine Emperor Gods Festival possesses “syncretistic” forms of worship found in the multi-ethnic, multi-religious cultural diasporas of Singapore and Malaysia (

Cheu 1993;

Heinze 1981). It has been cast as a venue where the cosmic power of the Nine Emperor Gods is renewed and human life is rejuvenated (

Cheu 1996). The scholarship on the festival is largely based on its Malaysian iterations, which have focused on the ethnic politics that have shaped the festival (

DeBernardi 2004). Yet these iterations are subjected to a whole host of socio-political conditions in a Malay-dominated state, shedding little light on the pressures the festival faces in Singapore.

Meanwhile, scholarship on Chinese religions in Singapore has largely focused on the tensions between religious practices and state actors. The state has actively constructed a domain within which local religions can operate, often rationalized as a means of maintaining harmonious relations between ethnic and religious groups (

Sinha 1999;

Sinha 2005;

Lai 2010). Scholars have also studied the simultaneous processes of transfiguration and hybridization, wherein Chinese practitioners transfigure sacred spaces and rituals to preserve ritual meanings in face of urbanization (

Goh 2009, p. 111;

Tong and Kong 2000, p. 41). Studies of spatial negotiations between divinities and the state have focused on Chinese spirit mediums operating out of house temples (

Heng 2016) and the mapping of sacrality onto urban spaces beyond designated sacred locales (

see Sinha 2016).

This paper is an anthropological study of the CCKDMG’s annual Nine Emperor Gods Festival. The temple was founded by the residents of the Inner Dong Cheng Village (

Nei Dong Cheng [内东城]) in 1921. Located at the 12½ milestone of Choa Chu Kang, it had its humble beginnings as an attap house, before moving into a house with a zinc roof.

2 In 1945, the temple moved to the Outer Dong Cheng Village (

Wai Dong Cheng [外东城]) (see

Figure 2). Chinese kampongs were hotbeds of Chinese religious activity and worship of the gods was an important communal bonding activity. When faced with relocation, Chinese residents “almost unanimously preferred to live in the kampong […] with its temple serving as a strong unifying point” (

Loh 2007, p. 19). Likewise, the CCKDMG was integral to the socio-religious life of its kampong, serving the religious needs of its Hokkien-Chinese community while having ties to village institutions like the Namsan Primary School.

3 A cluster of five sister temples eventually formed around the CCKDMG, hosting deities from the Taoist pantheon.

When in 1992 the temple’s land was acquired by the government for development, the CCKDMG was forced to relocate to their present location at Teck Whye. Its displacement came at the tail end of a series of kampong clearance and public housing policies that sought to fashion Singapore into a high modernist nation–state. Beginning in the early 1950s, the ruling People’s Action Party relocated kampong dwellers into high-rise public housing estates to “mold the semi-autonomous residents into model citizens of the high modernist nation-state” (

Loh 2009, p. 140). The state has also imagined and governed the spaces of Singapore as “an ‘efficient’, ‘orderly’ system in which the various needs of the population are taken care of” (

Kong 1993, p. 39).

Kong (

1993) argued that this ideologically hegemonic conception of space denies the socially significant and sacred meanings of spaces, instead emphasizing pragmatism and orderliness in allocating space. While the state allocates space for religious use, its recognition of religious needs is functionalist and “does not include the latent, private levels of meanings associated with religious places” (

Kong 1993, p. 37).

Following this, the CCKDMG and its annual festival are thus inevitably intertwined with the imposition of state authority upon the spaces of Singapore. Yet it remains undeniable that the festival celebrates the divine authority of the Nine Emperor Gods. How then, do we reconcile the tensions between state authority and divine authority during the festival? It is through an analysis of the negotiations between the impositions of state authority on the festival and the reproduction of divine authority in the festival’s rituals that this paper makes its key anthropological intervention.

2. Theoretical Orientation

The main theoretical thrust of this paper comes from Marshall Sahlins’ extension of the Hocartesian idea of inclusive “cosmic polities,” which proposes that “human societies were engaged in cosmic systems of governmentality” even before the existence of the human political state (

Sahlins 2017, p. 92). This paper borrows Sahlins’ idea that “the human social world is intrinsically part of a wider world in which boundaries between society and cosmos are non-existent,” wherein the powers-that-be are not only classically hegemonic, but also inscribed in practice such that devotees become the “dependent subjects of a cosmic system of social domination” (

Sahlins 2017, pp. 96–99). Most anthropological literature that theorizes the relationships between the Singaporean state and Chinese popular religion has separated the secular from the divine realm. Borrowing the idea of inclusive “cosmic polities,” I argue that these state–society–divine relations play out within an existing larger cosmological order wherein there exists no demarcation between the “secular” and “divine” realms. Instead, human, state, and divine actors co-participate in the same complex society. The Singaporean state is viscerally felt in the temple’s encounters with red tape and state regulations in the planning of the festival, and in the apparatuses through which it exerts power on the bodies of its practitioners. However, during the festival, sacrality emerges in previously secular domains such as public roads and the beach. These newly made sacred domains hold religious significances for devotees, who engage in imaginaries of an imperial bureaucracy ruled by the Nine Emperor Gods. Consequently, devotees conceive of both divine and state authority as shaping and limiting their personal freedoms, thus embodying the Hocartesian thesis that people live in a condition of subjugation to what Sahlins terms as “a host of metaperson powers-that-be,” both of the divine sovereigns and the secular state.

This paper borrows from anthropological literature on spatial exclusions in urban Asian cities. Harms wrote about “the paperwork mode of exclusion,” referring to the use of written documents to regulate people and their respective uses of space (

Harms 2016). Writing on governance in Islamabad, Matthew Hull argued that “the regime of paper documents” acts as an instantiation of social relationships between the government and the ground, creating a “peculiar mix of agency and subjection” (

Hull 2012, p. 163). I argue that the Singaporean state subjects the CCKDMG to its power by imposing “the paperwork mode of exclusion” on the temple. Foucault’s concept of governmentality has also informed my interpretation of the state authority imposed upon the CCKDMG. Like how “the network of power relations ends by forming a dense web that passes through apparatuses and institutions, without being exactly localized in them” (

Foucault [1978] 1990, p. 96), Foucauldian governmentality is manifested in state apparatus and state actors during the festival.

On popular Chinese religions, Anna Anagnost argued that the Chinese state and local communities are engaged in a “politics of ritual displacement,” where the rebuilding of temples and procession of local deities represent the symbolic reclamation of their own space from a totalizing party–state (

Anagnost 1994, pp. 222–23). Kenneth Dean argued that the “multiple public spheres” created by ritual actions of communities of believer–practitioners in southern Fujian challenge the cultural and ideological structures of the Chinese state (

Dean 1997). It remains noteworthy that anthropological literature on popular Chinese religions is mostly based on ethnographic work in China, where Chinese popular ritual in China has faced vastly different social pressures from its diasporic cousins. Unlike Chinese ritual life in China, which suffered from the anti-superstition campaigns of the Cultural Revolution, the Nine Emperor Gods Festival set roots in Singapore over a century ago and thus developed in a vastly different modern cultural context. The Nine Emperor Gods Festival in Singapore was subject to British colonial forces, then later, to the pressures of the ruling People’s Action Party, which pursued different politics of control than the outright suppression of Chinese popular religions in Nationalist and Communist China (

Goossaert and Palmer 2011). Nevertheless, these literatures provide useful references for interpreting the spatial negotiations between Chinese temples and the state.

This paper also borrows from anthropological literature on space and place. Gastón Gordillo analyzed the “materiality of memory, its embodiment in practice, and its constitution as a social force in the production of places” of the Toba people in the Argentina Chaco, arguing that the construction of space is a dynamic process that is deeply related to the spatiality of memory (

Gordillo 2004, p. 4). Low and Altman’s idea of “place attachment,” which refers to the “affective relationship of people to a space or piece of land and the associated symbolic meanings and modes of attachment” (

Low 2016, p. 78;

Altman and Low 1992), is also applicable to the CCKDMG. Borrowing from Nancy Munn’s notion of “mobile spatial fields,” where people produce space by moving through it (

Munn 1996), I propose that spirit mediums of the Nine Emperor Gods produce “divine spaces” when they are tranced.

4. Spatial Regulations, Divine Negotiations

4.1. State Regulations

Jie Lin: What are your main tasks at the temple?

John: Administrative, pre-event things. I apply for licenses. If you want to hold a festival, you need a police permit. You also need to get permission from the different stakeholders like the Singapore Land Authority [and], Land Transport Authority. Because you are using the road [and] the [state’s] land, you need permission from them to host events.

I first met John on the back of a lorry, when we were headed to the houses of devotees living across Singapore to collect their censers before the upcoming festival. On the one-hour journey from Teck Whye to Changi, I interviewed him about his experiences with the Nine Emperor Gods and the CCKDMG. In his early thirties, John joined the temple four years ago and is one of the youngest members of the temple’s male-only administrative committee (lishihui [理事会]), assisting in the temple’s pre-festival planning annually.

As the Nine Emperor Gods Festival is conducted in other locations beyond the temple’s premises, the CCKDMG must secure a permit from the Singapore Police Force (SPF) and licenses from the Singapore Land Authority (SLA), which regulates land-use, and the Land Transport Authority (LTA), which regulates road usage. As the festival usually takes place in either September or October, the temple begins applying for permits and licenses as early as January.

6 Referring to the red tape the temple faces in planning the festival, John said, “We don’t really want to drag [the planning] too far back because, you know, when the government processes the payments, it takes a while.” This need to obtain state permits and licenses can be characterized by “the paperwork mode of exclusion,” referring to “written documents that regulate people and the use of space” (

Harms 2016, p. 46). Without these permits, the temple will not have legal access to the spaces needed to perform rituals.

Beyond the annual permits for its festival, the temple must readily adapt to circumstances that necessitate additional permits. For one, the temple had historically held several of the festival’s key rituals in an open field behind its premises. When construction began on the open field for a public carpark by the Housing and Development Board (HDB) in 2016, the temple became pressed for time to secure another space in time for the festival. The

lishi set their sights on a public carpark located across the road from the temple. However, the process of obtaining a permit for this new ritual site was arduous. The

lishi Ah Jia camped at and surveyed the carpark for several consecutive nights, meticulously documenting its vehicular usage. With this newfound information, the committee then approached the Member of Parliament (MP) in their constituency to assist in talks with the HDB, which oversees the management of public housing estates.

7 Only by proving that the temple’s use of the carpark would not hinder the use of the carpark by public housing estate residents did the HDB issue the temple a permit to conduct its rituals there. These interactions reflect how the temple is encompassed within a “regime of paper documents” (

Hull 2012, p. 163). This regime produces a peculiar mix of agency where the temple is assisted by state actors like their MP while being subjected to restrictions imposed by state institutions. As obtaining permissions from various state bodies is crucial for the festival’s success, the state’s legal frameworks that promote spatial inclusions or perpetuate exclusions then instantiates the temple’s relationship with the state as one where it is subjected to the state’s regulatory powers.

This “regime of paper documents” is further instantiated by a state audit culture where the temple is required to submit annual financial reports to the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY). John said, “I don’t know if we can call ourselves a company, but we must submit a financial report every year. We engage a government-accredited accountant [to do the accounts] so that when we submit our financial report to MCCY, everything is accounted for.” Because the CCKDMG must overcome a lot of red tape to legalize and legitimize both the festival and the temple, the state’s regulatory institutions thus impose a regime of surveillance and governance over the CCKDMG.

State authority also emerges in regulations surrounding the temple’s physical structure. The state prohibits religious organizations from owning land, instead leasing out land to them. As a result, the CCKDMG is required to renew its land lease every 30 years, along with its sister temples who share the same premises. I have heard that the sum is “substantial” and requires a lot of saving up on the temple’s part. The CCKDMG’s land lease renewal is a source of anxiety for the

lishi, who are constantly seeking new means of attracting more sponsorships and donations for the temple. Throughout the temple, banners are put up seeking donations from devotees to raise money for the land deed renewal (see

Figure 3). As the current lease ends in 2022, the temple will need to renew it to continue remaining at Teck Whye, constituting another regulatory mechanism imposed upon the CCKDMG by the state.

These material encounters with state impositions allow the festival’s planners to imagine the Singaporean state as a draconian regime of regulation and surveillance. They also inspire reminiscences of their past encounters with the state—in particular, its forced resettlement and loss of important ritual sites. According to Uncle Xin, an “old-timer” who has served at the temple for 40 years, the prime location for the temple would be “on a hill facing the sea” to accumulate good

fengshui, but state-led urbanization has made that a distinct impossibility.

8 In these encounters, the

lishi reify their understandings of the state as a draconian force in both contemporary and historical contexts.

Yet these negotiations also allow the lishi to imagine a state that divine authority can negotiate with and even challenge. A focus on state regulations and the CCKDMG’s corresponding negotiations presents only half of the picture on the planning of the festival. In the next section, I present how the lishi construe their progress in the festival’s planning as the result of divine interventions, where the Nine Emperor Gods are prominent actors that speed up the planning process.

4.2. Divine Negotiations

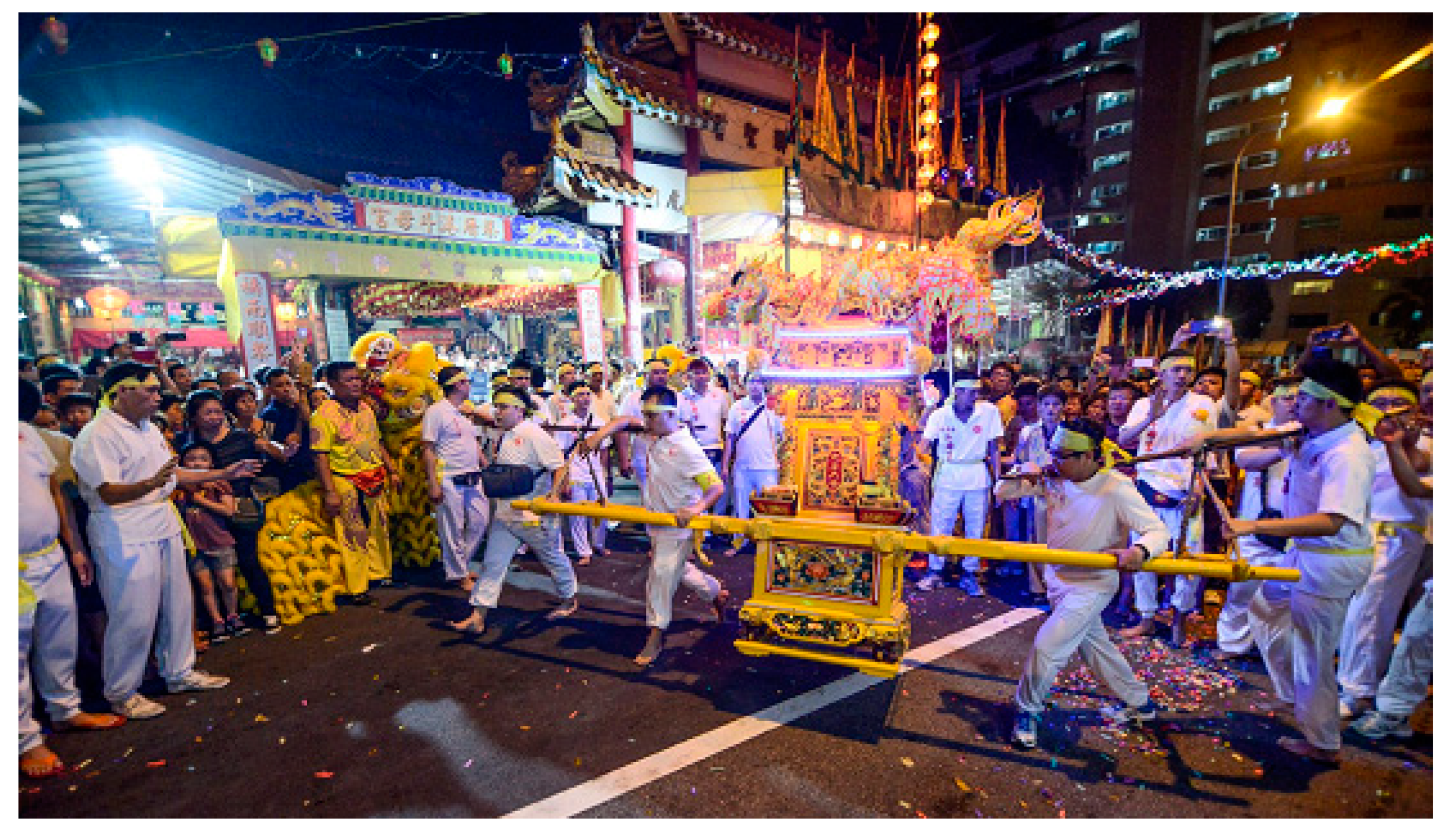

Ah Jia: I became surer [of my religious devotion] when I took over the making of the palanquins. [DaDi] said that a dragon needed to be included on the roof. I began to ask around to find out if anyone could recommend someone who knew how to carve dragon sculptures… [but] no one does that in Singapore anymore. During the weekends, I happened to be at Rochor Road and asked the stallholders if they knew anyone [but] they also said no. I felt very disappointed. I was about to go home [when] suddenly, it started raining heavily so I ran to the HDB blocks opposite […] I saw an auntie selling second-hand antique furniture. I asked her if she knew anyone who did carving jobs and she said yes. She proceeded to pass me the carver’s contact. I went to the carver’s place and […] I saw all his carving works. More importantly, one week before this incident, I went to the temple to pray for help as I was running out of time. I said, “Boss, could you please give me some advice?” A week later, I found the carver, so I think it was like a miracle. In the end, the palanquins were completed beautifully […] So all these “you qiu bi ying” [有求必应] (translated as “the gods answer all prayers”) situations kept my faith going strong. At times like these, you can call it a “coincidence” but it’s up to the individual on how they want to perceive [it].

In an interview, Ah Jia recounted his experience overseeing the making of the palanquins for the Nine Emperor Gods. The palanquins are some of the most important ritual items in the festival, being used in the processions, receiving and sending rituals. They are ornate covered litters that transport each emperor god from place to place during the festival. As the addition of dragon sculptures on the roof of the nine palanquins was ordered by the First Emperor God (DaDi [大帝]), Ah Jia faced pressure from the gods to complete the task. When time was running out, he sought the guidance of the Nine Emperor Gods by praying at their altar. Using the phrase “the gods answer all prayers,” Ah Jia attributed his eventual discovery of a local carver and the subsequent completion of the palanquins to the guidance of the Nine Emperor Gods. His anecdote is an example of how the lishi construe the Nine Emperor Gods as active agents in planning the festival.

Divine agency also surfaces in the temple’s negotiations with state regulations. Yi shifu, who has been the spirit medium (jitong [乩童]) for DaDi for 24 years, recounted how his National Service (NS) duties had clashed with his spirit medium responsibilities. In 1995, he was due to fly out of Singapore for NS training on the seventh day of the festival. Out of guilt for not fulfilling his role, he consulted DaDi about his difficulties. On the day he was due to fly, flights were miraculously delayed till the day after, allowing him to trance for DaDi before heading off for training. On another occasion where his NS duties clashed with the first day of the festival, Yi shifu prayed again to DaDi. He was once again allowed to fulfill his religious responsibilities when an army superior helped him obtain a letter stating that he had fulfilled his army duties. Yi shifu believes that such miraculous incidents reflect DaDi’s divine power, that it was only because of divine intervention that he could serve the Nine Emperor Gods during the festival.

Yi shifu’s anecdote represents a direct clash between state authority and divine authority. That he was almost unable to carry out his spirit medium duties for DaDi constituted an instance through which the state indirectly intervened in ritual practice—by laying claim over his body in the form of National Service. Subsequently, a series of “divine” coincidences that allowed him to fulfill his religious duties then represented divine negotiations with state regulations. In assisting Yi shifu in circumventing state-imposed demands on his body, the gods “recognized” the presence of state authority, negotiating it by engendering incidents like the delay in flights.

Responding to the state regulations on the temple and its practitioners, the gods become active agents in planning the festival. Interestingly, because these spatial negotiations involve the gods, the state, and the

lishi, they reflect how the gods, the state, and the temple all co-participate in an inclusive “cosmic polity” (

Sahlins 2017). While the Singapore state separates the divine realm as an object of religious worship from the “secular” realm, the divine awareness of state regulations and the state’s bodily claims over these spirit mediums nevertheless presents how the gods engage in the same dimension as the state, where there exists no demarcation between the “divine” and “secular.” This concept of inclusive “cosmic polity” will be further explicated in the following sections.

6. Spirit Mediums, Divine Bureaucracy

The divine bureaucracy and state power of the Nine Emperor Gods is further asserted in the festival’s other rituals, which construct “divine spaces” through the bodies of their spirit mediums. As Nancy Munn proposed, “space(s) defined by reference to an actor … can also be understood as a culturally defined, corporeal–sensual field of significant distances stretching out from the body in a particular stance or action at a given locale or as it moves through locales” (

Munn 1996, p. 93). The human body is thus constructed as a “mobile spatial field” that configures human interactions within or across a fixed space (

Munn 1996). Casting the tranced spirit medium as a “mobile spatial field,” I propose that they create “divine spaces” that manifest a divine bureaucracy for devotees to worship. Having been “caught” by the Nine Emperor Gods, the nine spirit mediums become simultaneously god and human, rendering their immediate vicinity a “divine space.” Subsequently, these “divine spaces” allow for the Nine Emperor Gods to assert their bureaucratized power and enact emperor–subject relations with their devotees.

As divine authority is physicalized in the bodies of the nine mediums, this enables devotees to concretely engage with the gods (see

Figure 10). When the spirit mediums fall into a trance, they lose control over their bodies. Recalling his first “trance” of a Nine Emperor God, one of the spirit mediums noted that he “got a

feeling, tried to resist it but was unable to and fainted.”

18 After he had accepted his role as a medium, the trancing became voluntary in nature; he would be conscious of the god “catching” his body and relinquish “most” of his consciousness to the god.

19 When trancing, each spirit medium rocks back and forth in his chair as his limbs violently shake and thrash about. Due to the intense nature of a trance, he had to be strongly held by assistants to prevent him from injuring himself unduly. It is these physical exertions that first alert devotees to the impending arrival of a Nine Emperor God.

When the god has “caught” a spirit medium’s body, the physical comportment of the latter differs drastically from his usual self. The Nine Emperor Gods are known to be stern deities that regard ritual very highly. In contrast, their mediums are affable men. For one, while Yi shifu is friendly and approachable, his comportment changes dramatically when DaDi enters his body. He bears an air of gravitas and is unsmiling. Once, I witnessed DaDi loudly admonishing an assistant for failing to carry out his orders, while repeatedly slamming his hand on the ritual table. As I watched on in shock, a devotee whispered to me that Yi shifu himself would not act and be angered in such a manner—reflecting how devotees recognize divine presences through the spatial practices of the Nine Emperor Gods. Thus, when these men assume the stern comportments of the deities, devotees recognize the divine presences, falling to their knees in obeisance. From there on, all actions are perceived to be carried out by the gods. The presence of their tranced spirit mediums further enhances the sense of subservience that a devotee feels towards the Nine Emperor Gods. While devotees typically kneel in an upright pose while praying to the Nine Emperor Gods at the temple’s main altar, their body language becomes significantly more servile when interacting with tranced mediums. The devotees hunch their backs and bow repeatedly, even after having completed the receiving of their blessing.

Spirit mediumship in Singapore is typically performed in a small temple or apartment where each session serves the needs of small groups of devotees, conjuring a certain level of intimacy between god and devotee (

see Heng 2016). Owing to the mass, bureaucratized nature of the rituals conducted during the Nine Emperor Gods Festival, I propose another perspective—that the presence of all nine spirit mediums at the rituals enhances the bureaucratic identities and consequently, state power of the Nine Emperor Gods. The trappings of this divine imperial state power are most prominent in two of the festival’s key rituals: the crossing of the Bridge of Safe Deliverance and the divine consultations (

wenshi).

6.1. Crossing the Bridge of Safe Deliverance

Held on the festival’s eighth day, the crossing of the Bridge of Safe Deliverance (

Ping An Qiao) is a ritual wherein the Nine Emperor Gods renew their annual blessings of peace and safety to their devotees.

21 Crossing in the order of their zodiac signs (the first being that of the Rat) while barefooted, devotees are first blessed by an emperor god, where he waves his ceremonial flag along the devotee’s body. They then cross the physical Bridge of Safe Deliverance to symbolically leave their misfortunes in the past (see

Figure 11). Descending the bridge, they are once again flanked by the emperor gods, who wave their ritual flags over their heads to complete their blessings.

As devotees take turns crossing the bridge, this procession of an undifferentiated public reflects the bureaucratic nature of the nine divinities. Although devotees possess different problems, they are equally subordinated to the gods. During the blessing process, the gods do not speak to devotees; interactions with them are mediated by the

lishi, who are identified by their “work uniform.”

22Beyond its portrayal of bureaucratic power, the crossing ritual engenders a divine spatiality within which the gods and their devotees perform emperor–subject relations. As the foremost emperor god,

DaDi is seated on his throne to oversee the proceedings of the ritual. Devotees seeking additional blessings approach

DaDi and kneel before him. He then waves his flag over devotees to bless them. From time to time,

DaDi leaves his seat to—in the words of an interlocutor—“inspect the proceedings at the bridge,” much like a mortal emperor surveying his subjects. Meanwhile, the

lishi take on roles reminiscent of a court official. They direct the flow of the crowd, instruct devotees on how to interact with the emperor god, and receive paper offerings on behalf of each god. That an audience with an emperor god is granted only after the

lishi’s mediation delineates the hierarchical power of the nine divinities, casting the crossing of the Bridge of Safe Deliverance in an imperial light. Furthermore, the ritual items bear parallels to the bureaucratic tools used by Chinese emperors. Apart from a flag, each Emperor God uses his personal chop with red ink to stamp on the shirts of devotees as a form of blessing.

23 The red chop echoes the function of an imperial seal, which was used to convey an emperor’s approval of petitions and issuance of decrees. The crossing ritual thus produces a hierarchy resembling that of the Chinese imperial state; the Nine Emperor Gods enact the roles in their namesakes with

DaDi as the preeminent Emperor God; the

lishi articulate this imperial hierarchy as “court officials” who mediate emperor–subject relations, while the devotees are the “citizens” at the bottom of the hierarchy, or, to extend this comparison, “documents” that have been “approved” by their emperor.

Aside from this imperial imagery, it is noteworthy that a

lishi described the annual act of having his clothing stamped by

DaDi’s chop as “renewing [his] passport or Certificate of Entitlement (COE).”

24 The comparison of

DaDi’s chop to official documents issued by the Singaporean state to

legitimize one’s citizenship and vehicle ownership reflects how this

lishi conceives of himself as not simply a citizen of the divine state, but a divine state that is bureaucratic in nature. This analogy of the official documents of the Singaporean state also showcases his conception of the secular and divine states—as one in which his citizenships of both need to be constantly renewed and re-legitimized via text acts.

Although many Singapore-based temples celebrate the festival, the CCKDMG is the only temple that possesses all nine spirit mediums for all Nine Emperor Gods. Many devotees journey across Singapore to CCKDMG annually to celebrate the festival. When I asked some about their choice to follow the CCKDMG instead of temples situated closer to their homes, they expressed that they chose CCKDMG because of its nine spirit mediums, whose presences they believe are reflective of the temple’s magical efficacy (

ling [灵]). John told me that, although he visited many temples in his youth, he joined the CCKDMG because he was struck by the presence of all nine mediums and had a “feeling” that the temple was the most efficacious of all temples he had encountered.

25While devotees see the nine mediums as instruments of the temple’s magical efficacy, these mediums also subject the devotees to the bureaucratic hierarchy engendered by their very presences, transforming devotees into imperial subjects. Some devotees told me that, although they may not attend the festival’s other rituals, they cross the Bridge of Safe Deliverance annually. They believe that their families’ peace and safety are highly dependent on the blessings from the Nine Emperor Gods, without which they may be harmed. When I asked Auntie Wu, who has followed the CCKDMG for 20 years, whether the gods have blessed her, she said half-jokingly, “If I have not been blessed, then why would I come back every year? So long as you come, (they) will bless you.” Auntie Geng, who has also followed the temple for 20-odd years, said:

Regarding my family, things were not proceeding smoothly, my children were sick … that’s why I came here. The gods helped me. All I asked of the gods were fulfilled. My husband’s job was finally smooth-sailing, and my daughter managed to attend school.

As the devotees conceive of “the gods” in an unnamed and general sense, this suggests that their affinities with the gods exist not on a personal level—being loyal to one god—but rather, towards all nine of the Emperor Gods as impersonal beings. While devotees attend this ritual for their personal well-being, their worship nevertheless unfolds against a communal and impersonal ritual. What seem like simple acts of worship to them are thus woven into complex processes of meaning-making, within which their participation has fashioned them into imperial subjects of the gods.

6.2. Divine Consultations

Equally revealing of the bureaucratic nature and state power of the Nine Emperor Gods is the divine consultation (

wenshi), another ritual wherein “divine spaces” assist devotees in imagining divine authority. Conducted only during the festival, the

wenshi are sessions where devotees approach the gods for one-on-one consultations to seek divine help to resolve all kinds of personal problems (see

Figure 12). The

wenshi schedule pinned on the temple’s main noticeboard says the following: “Ask only about your problems; seeking wealth is prohibited.”

26Wenshi is a highly formalized ritual that the temple regards strictly, and according to my interlocutors, devotees who attend it are often in “desperate need of help from the gods.” Devotees are required to collect queue numbers and wait for their turn to consult an Emperor God. When the devotee’s turn arrives, they then sit at the table and confide their issues in the Emperor God. Following this, the deity whispers his advice into the ear of his assistant, who then makes sense of and translates the divine advice to the devotee.

27 Like in the crossing of the Bridge of Safe Deliverance, the

wenshi involves ritual objects and text acts that embody the power of the imperial state. The desk of each Emperor God contains his personal chop, a writing brush, two types of red ink, four types of blank talismans (of the paper and cloth varieties), joss money, and incense sticks.

28 After relaying his advice, the Emperor God dips his brush in red ink and performs writing on a talisman, before he finalizes his blessing by stamping his chop on it. The assistants then dry off the excess ink on the talisman on a wad of incense sticks, before passing the talisman to the devotee. Depending on the nature of his or her problem, a devotee is either required to burn and drink it with water, or to simply carry it around at all times as a safety amulet. According to a

lishi, the magical efficacy of the safety amulet increases over time.

The structure of communication between devotee and deity during the wenshi echoes that of the relationship between an imperial subject and the magistrate, who deals with citizens and administers local government on behalf of the Chinese emperor. Although the gods speak to individual devotees, the wenshi session is still made impersonal by the queue system and the assistance of a lishi by the god’s side, thus highlighting its bureaucratic nature. Furthermore, as these sessions are conducted only on select days of the festival, they represent a once-in-a-year opportunity for devotees to communicate, albeit in a mediated fashion, with the gods. The infrequent nature of wenshi thus heightens the sense of bureaucratic distance from the Nine Emperor Gods.

Interestingly, the process is analogous to a key consultative mechanism of the Singapore state—the Meet-the-People session where citizens may approach their Member of Parliament (MP) for social, financial, and other forms of assistance.

29 Of greater interest, however, are the dissimilarities between the Meet-the-People’s session and the

wenshi, which in turn reveal the bureaucratic differences between the secular and divine states. While one may seek financial help from their MP, the Nine Emperor Gods will be angered if a devotee approaches them regarding money matters. According to a

lishi, the nine divinities “come down to save us, not for us to ask about matters like money.” This idea of salvation suggests that the Nine Emperor Gods offer forms of spiritual and religious assistance that exist beyond the secular means of the Singaporean state. Another distinction lies in the speed at which assistance from a god or the state arrives for the devotee or citizen. Divine assistance is actualized in ritual acts and objects like the god’s chop and talisman, both of which contain the element of immediacy. A devotee suffering from a grievous disease or malevolent spirits can immediately begin keeping them at bay with a safety amulet issued by the Emperor God. Conversely, social assistance from the Singaporean state is typically filtered through layers of bureaucratic red tape and can take weeks, or up to months, before ultimately reaching one in need. In short, while devotees can access both the divine and secular states, their relationship with the Singaporean state cannot be actualized in the same ways as their relationship with the nine deities.

6.3. The Question of Agency

Marshall Sahlins proposed a perspectival shift from “human society as the center of a universe unto which it projects its own forms […] to the ethnographic realities of people’s dependence on the encompassing metaperson-others who rule earthly order, welfare, and existence” (

Sahlins 2017, p. 117). Opposing Durkheim’s idea that God is an expression of society’s power, Sahlins argued that God in fact expresses the

lack of power of society, where people depend on divinity for matters of life and death. Likewise, it is through the Nine Emperor Gods Festival that the nine gods emerge as powerful figures who wield immense power over the lives of their devotees. The festival thus instantiates this lack of power of their devotees, who seek to better their lives through their participation in the festival’s rituals and by receiving blessings from the Nine Emperor Gods. Not only do devotees see attending the rituals as imperative to having a year free from harm, but the festival also makes manifest how devotees’ agencies are limited by the imposition of divine authority on their bodies.

During the festival, Ah Jia broke his leg and limped around the temple in crutches. When I asked several aunties how he broke his leg, they laughed and said that he did not go vegetarian when he should have. Consequently, the gods punished him with a broken leg. While Ah Jia’s injury may be simply attributed to a bad fall, other devotees conceived his mishap as divine punishment. They then regaled me with other stories of divine power, from the incident where a thief was unable to leave CCKDMG after stealing a censer, to one where a devotee knelt at the altar for hours despite not observing the vegetarianism for the festival.

30 When onlookers attempted to pull the lady to her feet, she simply could not budge, leading them to believe that she was suffering from divine punishment. Such incidents provide fertile ground for them to imagine the omnipresence of divinity in limiting their personal freedoms, especially during the festival. Moreover, my interlocutors often uttered the phrase “The gods watch all our actions.”

31 These words are reminiscent of the existence of “‘cosmic rules’ of human order” (

Sahlins 2017, p. 113), the enforcement of which allows gods to stake their bodily claims on their subjects. Disincentivized by the potentiality of divine punishment, the devotees relinquish their control over their bodies, even over what they consume. While I initially went vegetarian to gain rapport with my interlocutors, I increasingly wondered if my decision was also shaped by this fear of divine punishment.

The festival thus expands devotees’ understandings of agency from being merely human-centric and state-defined into the divinely sanctioned. Although the state views religious space in functionalist terms and does not recognize divine agency, the lishi and devotees nevertheless interact and negotiate with state bodies with their own set of divine logics, be it in divine negotiations with state regulations, or in small resistances against the traffic police. Interestingly, the Nine Emperor Gods Festival also reveals the similarities between both forms of authority. The festival’s planners are caught between a rock and a hard place: they cannot reject organizing the festival, for fear of incurring the wrath of the Nine Emperor Gods, yet it is also in the planning that the state imposes its authority upon them. Although both authorities enact different bureaucratic orders, both nevertheless possess an authoritarian ethos. Standing at the mercy of divine and state authority, the lishi and devotees recognize the fundamental limits of their personal agencies.

7. Conclusions

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival organized by the Choa Chu Kang Dou Mu Gong produces affective spaces wherein the practitioners’ and devotees’ imaginings of a larger inclusive cosmic polity ruled by the Nine Emperor Gods are strengthened and reinvigorated. State authority is manifested and reconstituted as a potent force limiting the agency of the festival’s planners, in the “paperwork mode of exclusion” (

Harms 2016), state audit culture, governmentality, and the state’s bodily claims on the spirit mediums. Ironically, these limitations also facilitate the emergence of the Nine Emperor Gods as active agents in the festival’s planning, where they engender miraculous occurrences to assist the

lishi and spirit mediums in performing their responsibilities. The festival thus expands devotees’ understandings of agency from being merely human-centric and state-defined into the divinely ordained.

These divine negotiations reflect how the Nine Emperor Gods, the state, and devotees participate in an inclusive “cosmic polity.” The festival’s processions and rituals physically enact a larger cosmological order that subjects state actors to divine authority, while allowing devotees to engage in imaginaries of an imperial bureaucracy. It is during the festival that the state fails to claim sacred domains that hold religious significances for devotees. The festival thus represents a potent tool through which human society, which includes the state, can be subsumed under this larger inclusive “cosmic polity.”

One question remains: is there resistance against the state? This paper was first conceptualized with the intention of uncovering how the Nine Emperor Gods Festival may constitute a form of resistance by the CCKDMG and its followers against state regulations. However, not only was this rhetoric of resistance not explicated by my interlocutors—resistance is not a product of their personal agencies—but it emerged as a by-product of their performance of their allegiances to the gods. While devotees resist state actors like the traffic police, this resistance merely exists as an extension of divine authority. Furthermore, the festival’s rituals demand obedience from devotees, be it in physical acts of submission or in limiting one’s diet. Thus, while divine agency may be conceived of as a liberating force for the CCKDMG against state authority, its authoritarian elements ultimately cast the agencies of the lishi, practitioners, and devotees in a limited light.