Religious Values and Young People: Analysis of the Perception of Students from Secular and Religious Schools (Salesian Pedagogical Model)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Religious School and Secular School: A Common Comparison

1.2. Salesian Pedaogical Model

1.3. Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

2.2. Population and Sample

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Procedure and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Analysis of the Axiological Perceptions of Religious and Secular School Students

3.2. Specific Analysis of the Sample of Salesian Students

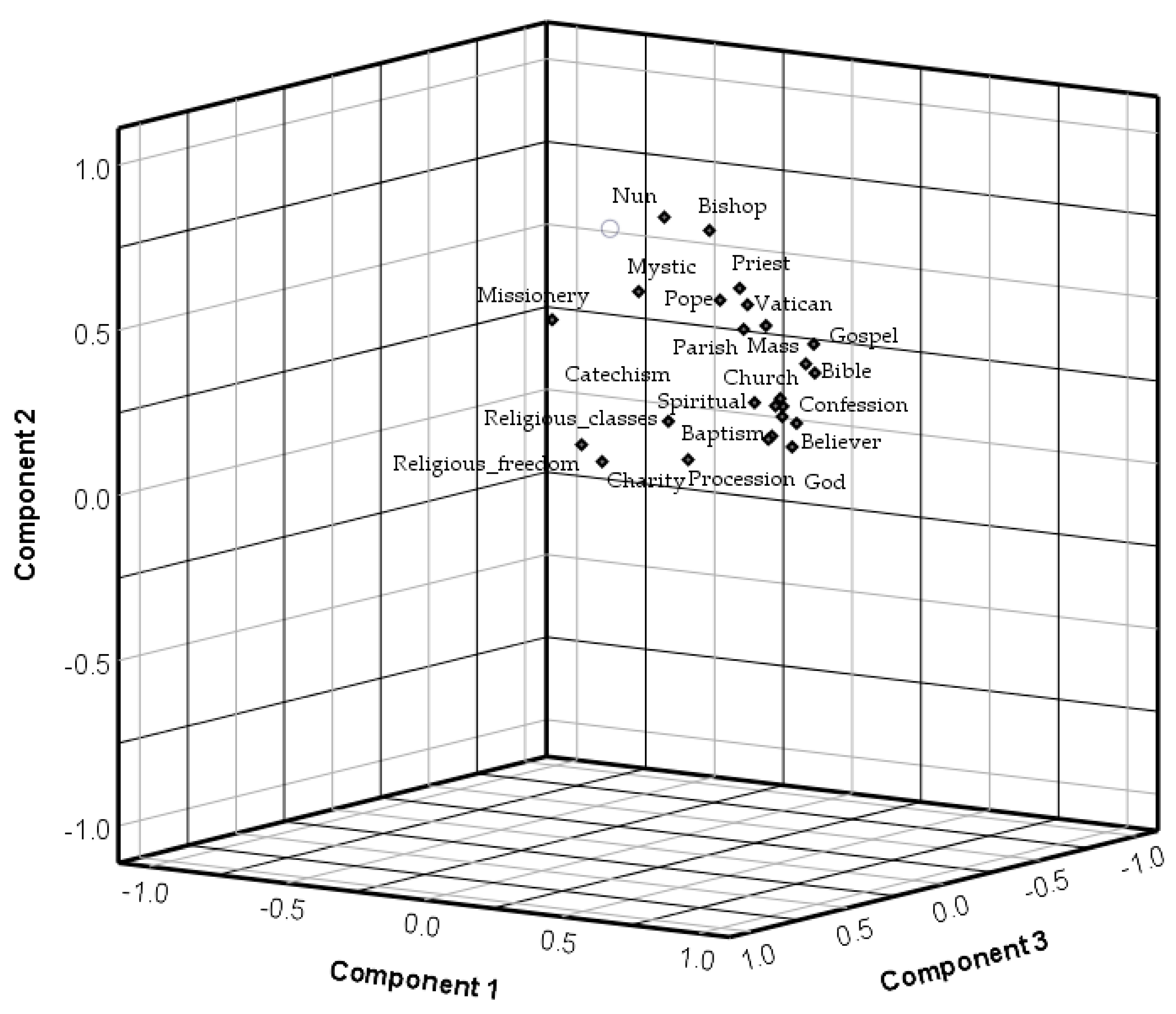

3.3. Main Results of the Calculated Factor Analysis

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Hierarchy of Values | School | Levene | Kolmogorov–Smirnov | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical | Sig. | Statistical | Sig. | ||

| Religious | Religious | 2.243 | 0.135 | 0.114 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.203 | 0.000 | |||

| Hierarchy of Values | School | Levene | Kolmogorov–Smirnov | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical | Sig. | Statistical | Sig. | ||

| Baptism | Religious | 1.708 | 0.192 | 0.300 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.225 | 0.000 | |||

| Bible | Religious | 2.007 | 0.157 | 0.197 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.282 | 0.000 | |||

| Charity | Religious | 0.588 | 0.443 | 0.320 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.265 | 0.000 | |||

| Catechism | Religious | 0.964 | 0.327 | 0.246 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.309 | 0.000 | |||

| Religious classes | Religious | 3.824 | 0.051 | 0.250 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.299 | 0.000 | |||

| Confession | Religious | 6.236 | 0.013 | 0.236 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.312 | 0.000 | |||

| Believer | Religious | 3.270 | 0.071 | 0.291 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.274 | 0.000 | |||

| Lent | Religious | 0.226 | 0.634 | 0.257 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.296 | 0.000 | |||

| God | Religious | 0.379 | 0.538 | 0.341 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.246 | 0.000 | |||

| Spiritual | Religious | 0.075 | 0.784 | 0.270 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.214 | 0.000 | |||

| Gospel | Religious | 2.734 | 0.099 | 0.220 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.303 | 0.000 | |||

| Church | Religious | 1.056 | 0.305 | 0.244 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.233 | 0.000 | |||

| Jesus Christ | Religious | 0.136 | 0.712 | 0.300 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.271 | 0.000 | |||

| Religious freedom | Religious | 0.669 | 0.414 | 0.297 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.258 | 0.000 | |||

| Mass | Religious | 8.716 | 0.003 | 0.183 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.328 | 0.000 | |||

| Missionary | Religious | 1.051 | 0.306 | 0.266 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.215 | 0.000 | |||

| Mystic | Religious | 6.935 | 0.009 | 0.212 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.283 | 0.000 | |||

| Nun | Religious | 10.114 | 0.002 | 0.176 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.342 | 0.000 | |||

| Bishop | Religious | 1.614 | 0.205 | 0.199 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.320 | 0.000 | |||

| Pope | Religious | 6.699 | 0.010 | 0.256 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.319 | 0.000 | |||

| Parish | Religious | 2.972 | 0.085 | 0.222 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.322 | 0.000 | |||

| Procession | Religious | 0.588 | 0.443 | 0.302 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.253 | 0.000 | |||

| Pray | Religious | 0.002 | 0.965 | 0.228 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.296 | 0.000 | |||

| Priest | Religious | 3.976 | 0.047 | 0.206 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.328 | 0.000 | |||

| Vatican | Religious | 3.445 | 0.064 | 0.207 | 0.000 |

| Secular | 0.300 | 0.000 | |||

| Hierarchy of Values | Gender | Levene | Kolmogorov–Smirnov | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical | Sig. | Statistical | Sig. | ||

| Baptism | Man | 3.480 | 0.063 | 0.234 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.363 | 0.000 | |||

| Bible | Man | 5.879 | 0.016 | 0.193 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.262 | 0.000 | |||

| Charity | Man | 10.170 | 0.002 | 0.234 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.409 | 0.000 | |||

| Catechism | Man | 6.622 | 0.011 | 0.198 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.319 | 0.000 | |||

| Religious classes | Man | 3.021 | 0.083 | 0.196 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.330 | 0.000 | |||

| Confession | Man | 3.574 | 0.060 | 0.188 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.282 | 0.000 | |||

| Believer | Man | 8.391 | 0.004 | 0.231 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.350 | 0.000 | |||

| Lent | Man | 3.390 | 0.067 | 0.196 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.320 | 0.000 | |||

| God | Man | 15.028 | 0.000 | 0.284 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.397 | 0.000 | |||

| Spiritual | Man | 3.018 | 0.084 | 0.189 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.348 | 0.000 | |||

| Gospel | Man | 3.507 | 0.062 | 0.200 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.283 | 0.000 | |||

| Church | Man | 4.190 | 0.042 | 0.178 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.307 | 0.000 | |||

| Jesus Christ | Man | 6.561 | 0.011 | 0.241 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.359 | 0.000 | |||

| Religious freedom | Man | 8.373 | 0.004 | 0.216 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.374 | 0.000 | |||

| Mass | Man | 0.789 | 0.375 | 0.211 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.236 | 0.000 | |||

| Missionary | Man | 3.402 | 0.066 | 0.195 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.334 | 0.000 | |||

| Mystic | Man | 0.359 | 0.550 | 0.233 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.217 | 0.000 | |||

| Nun | Man | 0.633 | 0.427 | 0.208 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.208 | 0.000 | |||

| Bishop | Man | 0.597 | 0.441 | 0.214 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.209 | 0.000 | |||

| Pope | Man | 1.738 | 0.189 | 0.225 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.317 | 0.000 | |||

| Parish | Man | 1.567 | 0.212 | 0.175 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.280 | 0.000 | |||

| Procession | Man | 7.478 | 0.007 | 0.221 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.380 | 0.000 | |||

| Pray | Man | 2.487 | 0.116 | 0.212 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.303 | 0.000 | |||

| Priest | Man | 0.603 | 0.438 | 0.225 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.259 | 0.000 | |||

| Vatican | Man | 1.976 | 0.161 | 0.197 | 0.000 |

| Woman | 0.245 | 0.000 | |||

References

- Alburquerque, Eugenio. 2013. Espiritualidad de don Bosco. Educación y Futuro 28: 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Aldwing, Carolyn M., Crystal L. Park, Yu-Jin Jeong, and Ritwik Nath. 2014. Differing Pathways between Religiousness, Spirituality, and Health: A Self-Regulation Perspective. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 6: 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, José. 2002. Análisis descriptivo de los valores sentimiento y emoción en la formación de profesores de la Universidad de Granada. Profesorado, Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado 6: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, José. 2006. Los valores afectivos en la formación inicial del profesorado. Estudio inicial. Cuestiones Pedagógicas 18: 121–41. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, José, and Clemente Rodríguez. 2008. El valor de la institución familiar en los jóvenes universitarios de la universidad de Granada. Bordón 60: 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Baeza, Jorge. 2013. Educación Superior e Inclusión Social: Una perspectiva desde las Instituciones Universitarias Salesianas. Educación y Futuro 28: 201–22. [Google Scholar]

- Barret, Jennifer. B., Jennifer Pearson, Chandra Muller, and Kenneth A. Frank. 2007. Adolescent religiosity and school contexts. Social Science Quarterly 88: 1024–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battol, Sadia. 2012. Gender differences in the academic achievement of mainstream and religious school students. Journal of educational Sciences & Psychology 2: 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2007. Los Retos de la Educación en la Modernidad Líquida. Barcelona: Gedisa. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, William. 2008. Secularización: ¿teoría o paradigma? Revista Colombiana de Sociología 32: 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Benedicto, Jorge. 2017. Informe Juventud en España 2016. Madrid: Instituto de la Juventud. [Google Scholar]

- Benefield, Margaret, Louis W. Fry, and David Geigle. 2014. Spirituality and Religion in the Workplace: History, Theory, and Research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 6: 175–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bering, Jesse M., Carlos H. Blasi, and David. F. Bjorklund. 2005. The development of “afterlife” beliefs in religiously and seculary schooled children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 23: 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braido, Pietro. 2001. El Sistema Preventivo. Prevenir no Reprimir. Madrid: CCS. [Google Scholar]

- Bruggeman, Elizabeth Leistler, and Kathleen J. Hart. 1996. Cheating, lying, and moral reasoning by religious and secular high school students. Journal of Educational Research 89: 340–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bychkov, Victor. 2019. Aesthetic Experience as a Spiritual Support of Homo Post-Secularis. Religions 10: 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara, África. 2010. Valores en futuros profesores de Secundaria. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 13: 113–21. [Google Scholar]

- Casabayó, Mónica, Juan Francisco Dávila, and Steven W. Rayburn. 2020. Thou shalt not covet: Role of family religiosity in anti-consumption. International Journal of Consumer Studies 44: 445–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaglià, Piera. 2013. La relación educativa en don Bosco: Un tesoro. Educación y Futuro 28: 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cívico, Andrea, Erika González, and Ernesto Colomo. 2019. Análisis de la percepción de valores relacionados con las TIC en adolescentes. Revista Espacios 40: 18. Available online: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a19v40n32/19403218.html (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Cnaan, Ram A., Richard J. Gelles, and Jill W. Sinha. 2004. Youth and Religion: The Gameboy Generation Goes to “Church”. Social Indicators Research 68: 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court, Deborah. 2016. How shall we study religious school culture? Religious Education 101: 233–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila, Juan Francisco, Mónica Casabayó, and W. Rayborn Steven. 2018. Religious or secular? School type matters as a moderator between media exposure and children’s materialism. International Journal of Consumer Studies 42: 779–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Shannon N., and Theodore N. Greenstein. 2009. Gender Ideology: Components, Predictors, and Consequences. Annual Review of Sociology 35: 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, Carlos. 2002. Las preocupaciones del profesor de religión. Revista Española de Pedagogía LX: 301–18. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, Rafael, Salvador Giner, and Fernando Velasco. 2006. Formas Modernas de Religión. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Dinham, Adam, and Martha Shaw. 2017. Religious Literacy through Religious Education: The Future of Teaching and Learning about Religion and Belief. Religions 8: 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzo, Javier. 2006. Los Jóvenes y la Felicidad. Madrid: PPC. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban, Francisco. 2018. Ética del Profesorado. Barcelona: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, James W., and Mary Lynn Dell. 2004. Stages of faith and identity: Birth to teens. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 13: 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullat, Octavi. 2006. Antropología de lo religioso. Bordón 58: 467–75. [Google Scholar]

- Funes, María Jesús. 2008. Informe Juventud en España. Tomo 4. Cultura, Política y Sociedad. Madrid: Instituto de la Juventud. [Google Scholar]

- García, Raiza, Mirian Grimaldo, and Eduardo Luis Manzanares. 2016. Jerarquía de valores entre estudiantes de secundaria de colegio religioso y colegio laico de Lima. Liberabit 22: 229–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gervilla, Enrique. 2000a. Un modelo axiológico de educación integral. Revista Española de Pedagogía 215: 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gervilla, Enrique. 2000b. Valores de la Educación Integral. Bordón 52: 523–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gervilla, Enrique. 2002. Educadores del futuro, valores de hoy. Revista de Educación de la Universidad de Granada 15: 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gervilla, Enrique. 2006. La enseñanza religiosa en los centros educativos. Bordón 58: 457–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gervilla, Enrique, Pilar Casares, Socoro Entrena, Gracia González, Francisco Javier Jiménez, Teresa Lara, Marcos Santos, and Andrés Soriano. 2018. Test de Valores Adaptado (TVA_adaptado). Registro de la Propiedad Intelectual No. 04/2017/1538. April 11. [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo, Aldo. 2012. Estudio Introductorio y Notas Históricas de Memorias del Oratorio. Madrid: CCS. [Google Scholar]

- Gobernado, Rafael. 2003. Consecuencias ideacionales del tipo de escuela (pública, privada religiosa y privada laica). Revista Española de Pedagogía LXI: 439–57. [Google Scholar]

- González-Anleo, Juan María. 2006. Sentidos y creencias religiosas de los jóvenes españoles. Bordón 58: 477–91. [Google Scholar]

- González-Anleo, Juan María. 2017a. Valores morales, finales y confianza en las instituciones: Un desgaste que se acelera. In Jóvenes Españoles Entre dos Siglos 1984–2017. Edited by Juan María González-Anleo and José A. López-Ruiz. Madrid: Fundación SM, pp. 13–52. [Google Scholar]

- González-Anleo, Juan María. 2017b. Jóvenes y religión. In Jóvenes Españoles Entre dos Siglos 1984–2017. Edited by Juan María González-Anleo and José A. López-Ruiz. Madrid: Fundación SM, pp. 235–80. [Google Scholar]

- González-Blasco, Pedro. 2006. La socialización religiosa de los jóvenes españoles: Familia y escuela. Bordón 58: 493–518. [Google Scholar]

- González-Gijón, Gracia, Enrique Gervilla, and Nazaret Martínez-Heredia. 2019. El valor religioso hoy y su incidencia en la enseñanza religiosa escolar. Publicaciones 49: 215–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciliano, Jesús. 2013. Don Bosco y los emigrantes. Educación y Futuro 28: 151–81. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmann, Joseph. 1984. Cognitive Morality and Cheating Behavior in Religious and Secular School Children. The Journal of Educational Research 77: 249–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2006. Religion in the Public Sphere. European Journal of Philosophy 14: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, Amos. 2007. The politics of national education: Values and aims of Israeli history curricula, 1956–1995. Journal of Curriculum Studies 39: 441–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, Nadi. 2007. Do students’ values change in different types of schools? Journal of Moral Education 36: 453–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, Kriistina, Petri Nokelainen, and Kirsi Tirri. 2014. Finnish secondary school students’ interreligious sensitivity. British Journal of Religious Education 36: 315–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, José Antonio. 2002. Las Naciones Unidas y el ámbito de la libertad religiosa: Una segunda mirada. Revista Española de Pedagogía LX: 209–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez, José Antonio. 2006. Libertad religiosa y enseñanza religiosa escolar en una sociedad abierta. Bordón 58: 599–614. [Google Scholar]

- Izcue, Maravillas. 2013. Conocer a Don Bosco hoy. Educación y Futuro 28: 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jokić, Boris. 2015. An easy A or a question of belief: Pupil attitudes to Catholic religious education in Croatia. British Journal of Religious Education 37: 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulska, Joanna. 2020. Religious Engagement and the Migration Issue: Towards Reconciling Political and Moral Duty. Religions 11: 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifshitz, Hefziba, and Rivka Glaubman. 2002. Religious and secular students’ sense of self-efficacy and attitudes towards inclusion of pupils with intellectual disability and other types of needs. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 46: 405–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipovetsky, Gilles. 2016. La Era del Vacío. Barcelona: Anagrama. [Google Scholar]

- López, Paco. 2015. Las intuiciones pedagógicas de Juan Bosco. Una lectura desde la educación social. Educació Social. Revista d´Intervenció Socioeducativa 6: 102–19. [Google Scholar]

- López-Ruiz, José A. 2017. La centralidad de la familia para los jóvenes: Convivencia, libertad y educación. In Jóvenes Españoles Entre dos Siglos 1984–2017. Edited by Juan María González-Anleo and José A. López-Ruiz. Madrid: Fundación SM, pp. 105–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mather, Darin M. 2018. Gender Attitudes in Religious Schools: A Comparative Study of Religious and Secular Private Schools in Guatemala. Religions 9: 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-García, Antonia, and María Dolores Villena-Martínez. 2018. Used Sources of Spiritual Growth for Spanish University Students. Religions 9: 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanni, Carlo. 2013. Los puntos clave del sistema preventivo. Educación y Futuro 28: 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, José Miguel. 2013. Don Bosco en el ocaso de la modernidad: Aproximación histórica-crítica al contexto que forjó al educador-pastor. Educación y Futuro 28: 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas. 1948. Declaración Universal de los Derechos Humanos. Available online: https://www.un.org/es/universal-declaration-human-rights/ (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. 2018. Desarrollo en la Adolescencia. Available online: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/dev/es/ (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Puelles, Manuel. 2006. Religión y escuela pública en nuestra historia: Antecedentes y procesos. Bordón 58: 521–35. [Google Scholar]

- Raban, Nicoleta, and Ileana Loredana. 2015. Religiosity and proactive coping with social difficulties in Romanian adolescents. Journal of Religion & Health 54: 1647–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Academia Española. 2019. Diccionario de la Lengua Española. Available online: https://dle.rae.es/ (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Rodríguez, Manuel, and Juan Jesús Iglesias. 2018. Don Bosco: Una propuesta educativa adecuada a los presos jóvenes. Salesianum 80: 109–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rojano, Jesús. 2009. ¿Son religiosos o no los jóvenes de hoy? Crítica 962: 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rojano, Jesús. 2013. La teología y moral que aprendió el joven Juan Bosco y la influencia en su obra. Educación y Futuro 28: 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, Javier. 2010. Jóvenes y religión en un mundo de cambio. El caso de los jóvenes chilenos. Ciencias Sociales y Religión 12: 147–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymarz, Richard, and Anthony Cleary. 2018. Examining some aspects of the worldview of students in Australian Catholic schools: Some implications for religious education. British Journal of Religious Education 40: 327–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, Francisco. 2013. El antiguo alumno en la pedagogía de don Bosco. Educación y Futuro 28: 223–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sander, William, and Danny Cohen-Zada. 2012. Religiosity and parochial school choice: Cause or effect? Educations Economics 20: 474–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schewel, Benjamin. 2018. Post-Secularism in a World-Historical Light: The Axial Age Thesis as an Alternative to Secularization. Religions 9: 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Avest, Ina, Dan-Paul Jozsa, and Thorsten Knauth. 2010. Gendered subjective theologies: Dutch teenage girls and boys on the role of religion in their life. Religious Education 105: 374–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuastad, Svein. 2016. What Is It Like to Be a Student in a Religious School? Religion & Education 43: 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uecker, Jeremy E. 2008. Alternative schooling strategies and the religious lives of American adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47: 563–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uecker, Jeremy E. 2009. Catholic schooling, protestant schooling, and religious commitment in young adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 353–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls, Maite. 2010. Las creencias religiosas de los jóvenes. In Jóvenes españoles 2010. Edited by Juan González and Pedro González. Madrid: Fundación SM, pp. 175–228. [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno, Eduardo. 2015. Espiritualidad líquida. Secularización y transformación de la religiosidad juvenil. OBETS. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 10: 437–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycka, Beata, Anna Tychmanowicz, and Dariusz Krok. 2020. Religious Struggle and Psychological Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Religious Support and Meaning Making. Religions 11: 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | School | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious (Salesian) | Secular | |||

| Students | 248 (54.39) | 208 (45.61) | 456 (100.00) | |

| Gender | Men (%) | 121 (48.79) | 94 (45.19) | 215 (47.15) |

| Women (%) | 127 (51.21) | 114 (54.81) | 241 (52.85) | |

| School year | 3rd (%) | 121 (48.79) | 96 (46.15) | 217 (47.59) |

| 4th (%) | 127 (51.21) | 112 (53.85) | 239 (52.41) | |

| Age | 14 (%) | 84 (33.88) | 69 (33.17) | 153 (33.55) |

| 15 (%) | 120 (48.38) | 97 (46.63) | 217 (47.59) | |

| 16 (%) | 39 (15.73) | 42 (20.20) | 81 (17.76) | |

| 17 (%) | 5 (2.01) | 0 (0) | 5 (1.10) | |

| Hierarchy of Values | N | Minimum Value Reached | Maximum Value Reached | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Affective | 248 | −4 | 50 | 38.56 | 9.51 |

| 2. Moral | 248 | −1 | 50 | 35.17 | 10.90 |

| 3. Individual | 248 | −6 | 50 | 33.54 | 10.20 |

| 4. Corporal | 248 | −4 | 50 | 29.04 | 8.62 |

| 5. Instrumental | 248 | −1 | 50 | 28.42 | 10.70 |

| 6. Ecological | 248 | −50 | 50 | 27.20 | 17.28 |

| 7. Social | 248 | −30 | 50 | 27.01 | 13.49 |

| 8. Religious | 248 | −50 | 50 | 23.55 | 21.96 |

| 9. Aesthetic | 248 | −30 | 50 | 19.37 | 13.64 |

| 10. Political Participation | 248 | −50 | 50 | 14.66 | 14.28 |

| 11. Intellectual | 248 | −46 | 50 | 12.50 | 15.43 |

| Hierarchy of Values | N | Minimum Value Reached | Maximum Value Reached | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Moral | 208 | 18 | 50 | 44.91 | 6.49 |

| 2. Individual | 208 | 11 | 50 | 43.48 | 7.85 |

| 3. Affective | 208 | 21 | 50 | 42.54 | 6.53 |

| 4. Ecological | 208 | 0 | 50 | 41.69 | 11.24 |

| 5. Social | 208 | 11 | 50 | 36.89 | 9.39 |

| 6. Corporal | 208 | 17 | 50 | 34.98 | 7.56 |

| 7. Aesthetic | 208 | 2 | 50 | 28.00 | 11.42 |

| 8. Instrumental | 208 | 0 | 50 | 26.28 | 11.84 |

| 9. Intellectual | 208 | −3 | 50 | 19.21 | 6.55 |

| 10. Political Participation | 208 | −9 | 50 | 17.11 | 7.73 |

| 11. Religious | 208 | −48 | 48 | −0.58 | 21.01 |

| Values Category | School | N | Means | Standard Deviation | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious | Religious | 248 | 23.55 | 21.96 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.58 | 21.01 |

| Hierarchy of Values | N | Minimum Value Reached | Maximum Value Reached | Means | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charity | 248 | −2 | 2 | 1.29 | 0.92 |

| God | 248 | −2 | 2 | 1.26 | 1.07 |

| Baptism | 248 | −2 | 2 | 1.19 | 0.99 |

| Religious freedom | 248 | −2 | 2 | 1.19 | 1.00 |

| Procession | 248 | −2 | 2 | 1.15 | 1.06 |

| Jesus Christ | 248 | −2 | 2 | 1.14 | 1.07 |

| Believer | 248 | −2 | 2 | 1.08 | 1.08 |

| Spiritual | 248 | −2 | 2 | 1.08 | 1.05 |

| Missionary | 248 | −2 | 2 | 1.08 | 1.03 |

| Lent | 248 | −2 | 2 | 1.02 | 1.04 |

| Religious classes | 248 | −2 | 2 | 1.00 | 1.12 |

| Pray | 248 | −2 | 2 | 1.00 | 1.06 |

| Catechism | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.96 | 1.08 |

| Church | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.92 | 1.14 |

| Confession | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.90 | 1.14 |

| Pope | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.87 | 1.13 |

| Parish | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.86 | 1.11 |

| Gospel | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.85 | 1.09 |

| Bible | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.83 | 1.13 |

| Priest | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.75 | 1.11 |

| Vatican | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.67 | 1.15 |

| Mystic | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.65 | 1.10 |

| Mass | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.64 | 1.17 |

| Bishop | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.60 | 1.09 |

| Nun | 248 | −2 | 2 | 0.59 | 1.16 |

| Hierarchy of Values | N | Minimum Value Reached | Maximum Value Reached | Means | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charity | 208 | −2 | 2 | 1.02 | 1.02 |

| God | 208 | −2 | 2 | 0.09 | 1.22 |

| Baptism | 208 | −2 | 2 | 0.24 | 1.15 |

| Religious freedom | 208 | −2 | 2 | 1.04 | 1.11 |

| Procession | 208 | −2 | 2 | 0.05 | 1.15 |

| Jesus Christ | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.08 | 1.18 |

| Believer | 208 | −2 | 2 | 0.05 | 1.11 |

| Spiritual | 208 | −2 | 2 | 0.47 | 1.07 |

| Missionary | 208 | −2 | 2 | 0.35 | 1.11 |

| Lent | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.14 | 1.12 |

| Religious classes | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.19 | 1.02 |

| Pray | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.08 | 1.13 |

| Catechism | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.31 | 1.04 |

| Church | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.43 | 1.19 |

| Confession | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.27 | 1.03 |

| Pope | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.37 | 1.05 |

| Parish | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.30 | 1.06 |

| Gospel | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.22 | 1.08 |

| Bible | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.21 | 1.10 |

| Priest | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.37 | 1.03 |

| Vatican | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.44 | 1.06 |

| Mystic | 208 | −2 | 2 | 0.14 | 1.07 |

| Mass | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.32 | 1.04 |

| Bishop | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.44 | 1.03 |

| Nun | 208 | −2 | 2 | −0.31 | 1.00 |

| Hierarchy of Values | School | N | Means | Standard Deviation | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charity | Religious | 248 | 1.29 | 0.92 | 0.002 * |

| Secular | 208 | 1.02 | 1.02 | ||

| God | Religious | 248 | 1.26 | 1.07 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | 0.09 | 1.22 | ||

| Baptism | Religious | 248 | 1.19 | 0.99 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | 0.24 | 1.15 | ||

| Religious freedom | Religious | 248 | 1.19 | 1.00 | 0.199 * |

| Secular | 208 | 1.04 | 1.11 | ||

| Procession | Religious | 248 | 1.15 | 1.06 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | 0.05 | 1.15 | ||

| Jesus Christ | Religious | 248 | 1.14 | 1.07 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.08 | 1.18 | ||

| Believer | Religious | 248 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | 0.05 | 1.11 | ||

| Spiritual | Religious | 248 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | 0.47 | 1.07 | ||

| Missionary | Religious | 248 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | 0.35 | 1.11 | ||

| Lent | Religious | 248 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.14 | 1.12 | ||

| Religious Classes | Religious | 248 | 1.00 | 1.12 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.19 | 1.02 | ||

| Pray | Religious | 248 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.08 | 1.13 | ||

| Catechism | Religious | 248 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.31 | 1.04 | ||

| Church | Religious | 248 | 0.92 | 1.14 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.43 | 1.19 | ||

| Confession | Religious | 248 | 0.90 | 1.14 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.27 | 1.03 | ||

| Pope | Religious | 248 | 0.87 | 1.13 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.37 | 1.05 | ||

| Parish | Religious | 248 | 0.86 | 1.11 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.30 | 1.06 | ||

| Gospel | Religious | 248 | 0.85 | 1.09 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.22 | 1.08 | ||

| Bible | Religious | 248 | 0.83 | 1.13 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.21 | 1.10 | ||

| Priest | Religious | 248 | 0.75 | 1.11 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.37 | 1.03 | ||

| Vatican | Religious | 248 | 0.67 | 1.15 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.44 | 1.06 | ||

| Mystic | Religious | 248 | 0.65 | 1.10 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | 0.14 | 1.07 | ||

| Mass | Religious | 248 | 0.64 | 1.17 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.32 | 1.04 | ||

| Bishop | Religious | 248 | 0.60 | 1.09 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.44 | 1.03 | ||

| Nun | Religious | 248 | 0.59 | 1.16 | 0.000 * |

| Secular | 208 | −0.31 | 1.00 |

| Hierarchy of Values | Gender | N | Means | Standard Deviation | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charity | Man | 121 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.56 | 0.69 | ||

| God | Man | 121 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.50 | 0.85 | ||

| Baptism | Man | 121 | 0.96 | 1.06 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.42 | 0.87 | ||

| Religious freedom | Man | 121 | 0.88 | 1.07 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.47 | 0.83 | ||

| Procession | Man | 121 | 0.86 | 1.14 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.42 | 0.90 | ||

| Jesus Christ | Man | 121 | 0.90 | 1.17 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.37 | 0.92 | ||

| Believer | Man | 121 | 0.83 | 1.17 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.33 | 0.92 | ||

| Spiritual | Man | 121 | 0.79 | 1.09 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.35 | 0.94 | ||

| Missionary | Man | 121 | 0.81 | 1.08 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.33 | 0.92 | ||

| Lent | Man | 121 | 0.75 | 1.08 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.28 | 0.94 | ||

| Religious Classes | Man | 121 | 0.70 | 1.16 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.28 | 1.00 | ||

| Pray | Man | 121 | 0.72 | 1.11 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.26 | 0.95 | ||

| Catechism | Man | 121 | 0.62 | 1.12 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.29 | 0.94 | ||

| Church | Man | 121 | 0.64 | 1.20 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.18 | 1.03 | ||

| Confession | Man | 121 | 0.65 | 1.17 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.13 | 1.06 | ||

| Pope | Man | 121 | 0.60 | 1.16 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.13 | 1.04 | ||

| Parish | Man | 121 | 0.64 | 1.16 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.07 | 1.03 | ||

| Gospel | Man | 121 | 0.55 | 1.13 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.14 | 0.97 | ||

| Bible | Man | 121 | 0.51 | 1.19 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 1.13 | 0.98 | ||

| Priest | Man | 121 | 0.50 | 1.12 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 0.98 | 1.05 | ||

| Vatican | Man | 121 | 0.43 | 1.22 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 0.89 | 1.03 | ||

| Mystic | Man | 121 | 0.42 | 1.12 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 0.87 | 1.03 | ||

| Mass | Man | 121 | 0.32 | 1.18 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 0.94 | 1.09 | ||

| Bishop | Man | 121 | 0.37 | 1.06 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 0.81 | 1.09 | ||

| Nun | Man | 121 | 0.36 | 1.10 | 0.000 * |

| Woman | 127 | 0.81 | 1.17 |

| Means of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Adequacy of the Sample | 0.962 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s Sphericity Test | approximate chi-squared | 6980.816 |

| Gl | 300 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 * | |

| Comp. | Initial Self Values | Sums of Charges Squared Extraction | Sums of Charges Squared Extraction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % Variance | % Accumulated | Total | % Var. | % Acc. | Total | % Var. | % Acc. | |

| 1 | 16.515 | 66.06 | 66.06 | 16.515 | 66.06 | 66.06 | 9.38 | 37.52 | 37.52 |

| 2 | 1.328 | 5.31 | 71.37 | 1.328 | 5.31 | 71.37 | 5.76 | 23.02 | 60.54 |

| 3 | 1.010 | 4.04 | 75.41 | 1.010 | 4.04 | 75.41 | 3.72 | 14.87 | 75.41 |

| Religious Values | Component | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Charity | 0.395 | 0.203 | 0.752 |

| God | 0.789 | 0.226 | 0.327 |

| Baptism | 0.714 | 0.251 | 0.325 |

| Religious freedom | 0.299 | 0.240 | 0.721 |

| Procession | 0.532 | 0.186 | 0.500 |

| Jesus Christ | 0.761 | 0.258 | 0.412 |

| Believer | 0.799 | 0.297 | 0.318 |

| Spiritual | 0.710 | 0.364 | 0.409 |

| Missionary | 0.125 | 0.587 | 0.626 |

| Lent | 0.760 | 0.372 | 0.347 |

| Religious classes | 0.473 | 0.299 | 0.518 |

| Pray | 0.757 | 0.315 | 0.334 |

| Catechism | 0.744 | 0.349 | 0.349 |

| Church | 0.737 | 0.451 | 0.183 |

| Confession | 0.700 | 0.328 | 0.248 |

| Pope | 0.511 | 0.639 | 0.305 |

| Parish | 0.589 | 0.557 | 0.294 |

| Gospel | 0.758 | 0.511 | 0.171 |

| Bible | 0.759 | 0.423 | 0.167 |

| Priest | 0.542 | 0.669 | 0.248 |

| Vatican | 0.542 | 0.613 | 0.206 |

| Mystic | 0.277 | 0.653 | 0.392 |

| Mass | 0.621 | 0.561 | 0.223 |

| Bishop | 0.400 | 0.823 | 0.202 |

| Nun | 0.236 | 0.847 | 0.201 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cívico Ariza, A.; Colomo Magaña, E.; González García, E. Religious Values and Young People: Analysis of the Perception of Students from Secular and Religious Schools (Salesian Pedagogical Model). Religions 2020, 11, 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11080415

Cívico Ariza A, Colomo Magaña E, González García E. Religious Values and Young People: Analysis of the Perception of Students from Secular and Religious Schools (Salesian Pedagogical Model). Religions. 2020; 11(8):415. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11080415

Chicago/Turabian StyleCívico Ariza, Andrea, Ernesto Colomo Magaña, and Erika González García. 2020. "Religious Values and Young People: Analysis of the Perception of Students from Secular and Religious Schools (Salesian Pedagogical Model)" Religions 11, no. 8: 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11080415

APA StyleCívico Ariza, A., Colomo Magaña, E., & González García, E. (2020). Religious Values and Young People: Analysis of the Perception of Students from Secular and Religious Schools (Salesian Pedagogical Model). Religions, 11(8), 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11080415