‘Purest Bones, Sweet Remains, and Most Sacred Relics.’ Re-Fashioning St. Kazimierz Jagiellończyk (1458–84) as a Medieval Saint between Counter-Reformation Italy and Poland-Lithuania

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Purest Bones, Sweet Remains, and Most Sacred Relics

Rejoice, noble and splendid Italy, from which arose both Litalinian [sic] and Lithuanian high nobility, from which was also born Casimirus, whose primeval origin was there.1 Rejoice vast and spacious Sarmatia for conquering frost, cold and your own barrenness, to produce this most beautiful and blissful tree of life, yielding the sweetest fruit of virtue and honor. Rejoice holy and pious Mother Church, for bringing into the light Casimir as a true son of Christ and a warrior for the faith. Rejoice Poland for its most religious kings and Lithuania for its most magnificent dukes. Above all, rejoice Vilnius—the glorious city, where Casimir’s purest bones, sweet remains, and most sacred relics will be kept for posterity as a guarantee of his immortality and glory(Ferreri 1521a, n.p.).2

2. MALO MORI QUAM FOEDARI: The Making of St. Kazimierz between Italy and Lithuania

- Casimir gives a bright dawn

- to the desired joys

- of both Italy and Sarmatia,

- from whence he derives his origin […]

- Better to die than transgress

- the boundaries of chastity […]

- Defend your people

- against the frenzy of war,

- against the Scythians and impious

- sects and other schisms.7

3. It Was the Polar Winds That Have Led Me to the Conquest of the Sacred Treasure: St. Kazimierz and His Relics between Vilnius and Florence

It was the Polar Winds that have led me to the conquest of the sacred Treasure that is the longed-for relic of the saintly King [sic] Casimiro, with which I already see myself rewarded, when I will row my vessel through the danger of a thousand difficult obstacles and abysses before arriving at its possession. My heart cannot find words to express the joy that flooded my soul upon opening the message from Vilnius […] from whence comes to me such a precious and inestimable gift […] I now remain in a state of most joyous righteous impatience, as I hope for the venerable Relic….

4. Whose Conquest Was Sought through the Pilgrimage of Both the Pen and the Mind: Translating St. Kazimierz Jagiellończyk and St. Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi

I cannot contain my immense pleasure from the joyful satisfaction of my great longings upon yesterday’s arrival of the sacred Treasure, whose conquest was sought through the pilgrimage of both the pen and the mind, with the desire to reward myself. I speak of the inestimable relic of Glorious Prince St. Casimiro, which was accompanied by rich ornament: namely, a precious altar furnishing to safeguard the relic. These were handed over to me in this city [of Florence] by the Lord Abbot and by a gentleman of My Lord the Bishop of Vilnius, on behalf of him and the Vilnius Cathedral chapter.

5. Conclusions: “Relic States”

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Aspects of research towards this article were presented at the following international conferences and workshops: “Performing Gifts. Rituals, Symbolic Communication and Gift-Giving in Medieval and Early Modern Europe” (Tallinn University, 2019), “Annual Meeting of the Renaissance Society of America” (2021), “The Noble Family of Pacowie (Pacai) of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Lithuanian Baroque” (Kaunas, 2021), “Sacred Books, Holy Relics and Godly Women: New Perspectives on Sanctity in Renaissance Europe. New trends in the humanities seminar series” (University of Oslo, 2021). Sincere thanks to Nils Holger Petersen for insights and support towards the preparation of this article, and to the Religions reviewers for valuable feedback. |

| 2 | Adapted from translations in (Briedis 2008, p. 38 and Dini 2014, p. 50). Unless otherwise specified, all translations are the author’s own. For the Krakow edition of Vita Beati Casimiri Confessoris see e.g., Rome, Biblioteca Nazionale, 14. 28.C.31.1. An edition was also published in Torún: see e.g., Lublin, Biblioteka Uniwersytecka KUL, XVI.499. For a composite copy with material from both editions see Krakow, Biblioteka Jagiellońska, BJ St. Dr. Cim. 4858. |

| 3 | On Ferreri see (Stöve 1996) and further citations below. |

| 4 | On the history of the cult of St. Kazimierz with special attention to the Italo–Lithuanian sphere see (Maslauskaitė-Mažylienė 2010, 2013). |

| 5 | For overviews of Lithuania in the premodern era see (Kiaupa et al. 2000; Davies 2013). |

| 6 | For relic translatio in the period under discussion here, see (Achermann 1981; Hills 2016); more generally, see (Heinzelmann 2002). |

| 7 | “Dat Casimiri lucida/Dies cupita gaudia /et italis, et sarmatis, /accepit unde originem…Mori magis, quam transgredi/ Pudicitatis limitem…Tu puritatis lilium…Tuum genus defendito/ Contra furores bellicos, /Contra scytas, et impias/ Sectas, et al. tra schismata….” In (Ferreri 1521a, n.p.). |

| 8 | On Reformation tensions in the Rzeczpospolita during this early period see (Nowakowska 2014; Kriegseisen et al. 2016, pp. 319–413). More broadly, Ferreri took part in reforming the Breviary, and published an oration on Church reforms (Ferreri 1523) that was later republished by the Tridentine Council (Stöve 1996). |

| 9 | In (Nowakowska 2014, p. 57). |

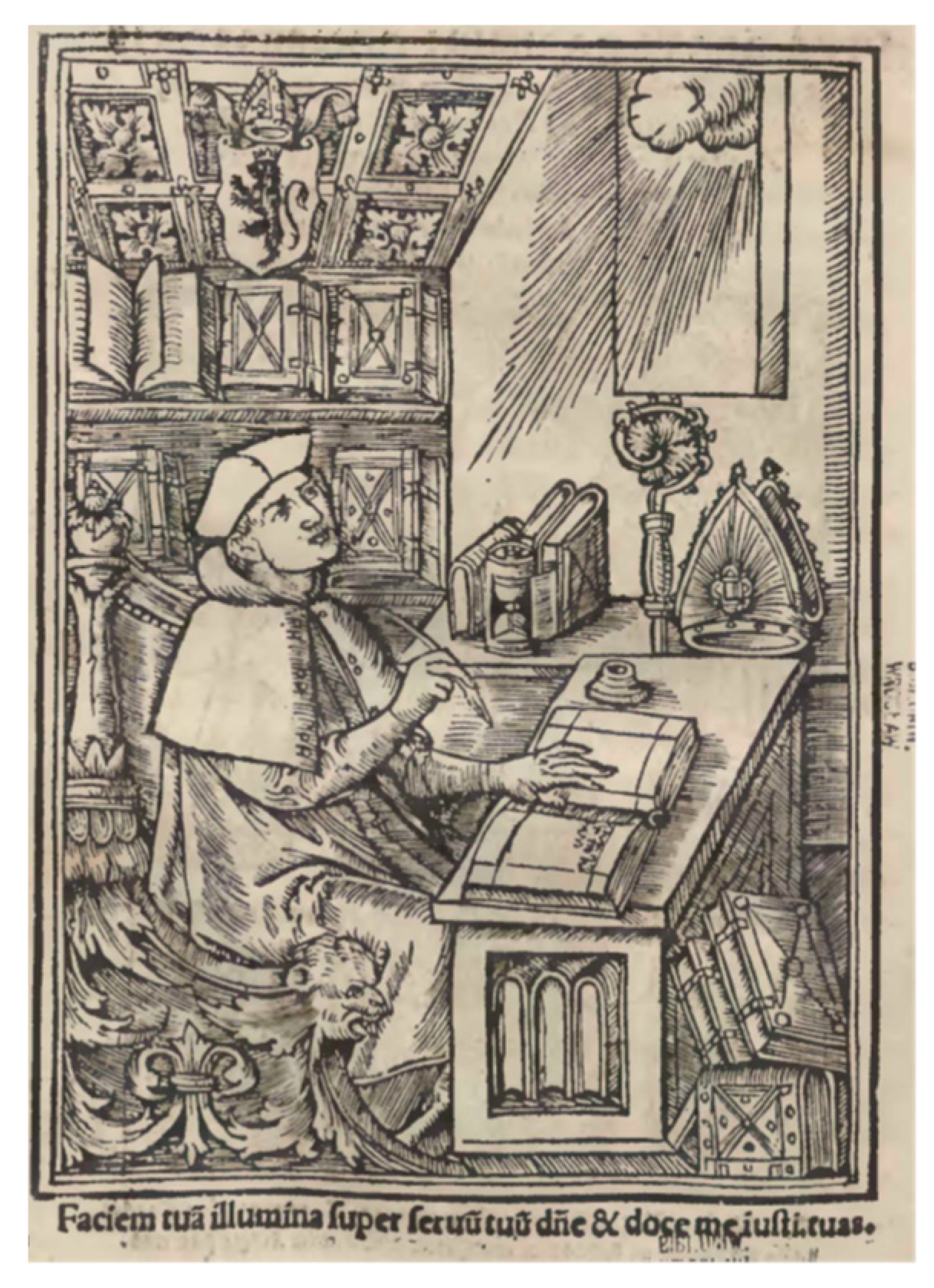

| 10 | For more on the saint’s woodcut portrait see further discussion below. |

| 11 | On the long history of spiritual martyrdom see (Rush 1962). |

| 12 | See also (Dini 2010). |

| 13 | |

| 14 | “Lithuanos […] Latini generis esse, etsi non a Romanis, saltem ab aliqua gente Latini nominis descendisse….” Although Długosz’s work was published in the seventeenth century, it circulated widely in manuscript during the prior century: see (Długosz 1615). On Długosz see (Papée 1939–1946; Knoll 1982). |

| 15 | On the history of this order see (Urban 2003); with reference to Lithuania (Petrauskas 2012). |

| 16 | On the Lithuanian crusades from the thirteenth century see (Murray 2010; Petrauskas 2012). |

| 17 | See (Długosz 1982). |

| 18 | See also: “Moscovitae irati imprecantur alicui suorum, us fiat Romanae sive Polonicae religionis. adeo eam exosam habent. Gymnasiis literatiis, dolendum, caremus. literas Moscoviticas nihil antiquitatis complectentes, nullam ad virtutem efficaciam habentas ediscimus, cum idioma Ruthenum alienum sit a Nobis Lithuanis, hoc est, Italico Sanguine oriundis.” (Angry Muscovites, they call down on any of their followers, be it Roman or Polish religion. they hate her so much. Unfortunately, we lack literary schools. We learn from the Muscovite letters which have no antiquity, and have no efficacy, we learn, since the Russian language is foreign to us from Lithuanians, that is, originating from the Italian blood.) In (Lituanos 1615, p. 23). |

| 19 | See (Orzeł 2010). |

| 20 | On Pograbka see (Hajdukiewicz 1982–1983). |

| 21 | (Jerzy 1987). |

| 22 | See e.g., (Guagnini 1581, pp. 45r-v). On the author see (Ronchi De Michelis 2003). |

| 23 | See e.g., Historiae Lituanae (History of Lithuania) by Jesuit and Deputy Vice Chancellor of Lithuania Albert (Wojciech) Wijuk Kojałowicz (1609–1677) (Wijuk Kojałowicz 1650, pp. 28–47), and further examples below. |

| 24 | For the Medici’s promotion of the Pazzi cult see (Copeland 2016; Modesti 2020, pp. 225–41). For the Lithuanian context see (Baniulytė 2010).) |

| 25 | For this historicizing see especially the scholarship of A. Baniulytė, including (Baniulytė 2003, 2005b, 2007, 2009). |

| 26 | e.g., papal nuncio in Poland–Lithuania Pietro Vidoni (1611–1681) wrote to Rome in 1654 of Lithuanian grand marshal Kristof Pac (1621–1684), whom he called “Christoforo de Pazzi,” that “che reale origine [era] da quella di Firenze” (his real origin is from Florence). See Rome, Archivio Segreto Vaticano (ASV), Nunziatura di Polonia, vol. 62, fols. 323v-324r. |

| 27 | On Stefan Pac see (Czapliński 1979). |

| 28 | Rome, Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu (hereafter ARSI), Epistolae Externorum, vol. 36, fol. 1r-v. For relevant archival sources pertaining to the exchanges taken up in the ensuing sections of this article see records preserved in Florence, Archivio di Stato Firenze (hereafter ASF), f. Mediceo del Principato: 1529–1753 (hereafter MP), 4489–4494, especially 4492, 298r-v, 442r-v, 561r, 604r, 697r; 4493, 602r-v, 603-604, 608r-v, 609r-v. |

| 29 | On Cosimo III see (Guarini 1984). |

| 30 | See also ASF, MP 4493, fols. 470r-v, 472 r-v, 602r-v. |

| 31 | On Bishop Pac see (Rachuba 1979). |

| 32 | Pacowie relations with Italy and Medicean Tuscany have been taken up in a number of important multilingual studies by Aušra Baniulytė and Anna Sylwia Czyż cited below and throughout this essay. See also (Noyes forthcoming). |

| 33 | On the history of this order see (Urban 2003). |

| 34 | For published period primary sources related to Italian promotion of Casimir’s cult see (Hilarione di S. Antonio 1629; Rosselli 1642; Sobecki 1674; Skarbek 1684). |

| 35 | For aspects of Italo–Baltic historical relations during the Middle Ages and Early Modern eras, see (Brahmer 1980; Lewanski 1994; Baniulytė 2005a; Bugiani 2007; Mitrulevičiūtė 2016; Guidetti 2018), and additional citations below. |

| 36 | The painting’s notoriety is suggested by the fact that Dolci made a copy of the work, which is illustrated here. |

| 37 | For an overview of the Baltic crusades see also (Murray 2001). |

| 38 | For studies in Baltic cultural geography see (Tamm 2009) and other studies in (Murray 2009). For connections between the Holy See and Poland–Lithuania in this period see (Platania 1992, 2000, 2011). |

| 39 | For the topos of Antemurale Christianitatis see (Srodecki 2015; Rowell 2002). For the topoi of “womb of nations” and “indies of Europe” see, respectively, (Donecker 2018) and (Morawski 1989; Caccamo 2010; Donecker 2016). On the Baltic as commodity frontier see (Moore 2010a, 2010b). For Baltic biodiversity see (Jørgensen 2018); on the fur trade see (Martin 1986). For the rumored but never realized prospect of precious metals in the region see (Kudachinova 2019). |

| 40 | For early hagiography of Kostka in Italy, see (Sacchini 1610a, 1610b); for Kuncewicz, see (Gerardi 1643; Borovio 1644; Susza 1665, 1666). For secondary literature on Kostka’s cult in Rome (also the site of his death) see (Levy 1997); for Kuncewicz (Jobst 2012). |

| 41 | For these circumstances and the dispersal of Kazimierz’s relics see (Theatrum S. Casimiri 1604; Žygas 1996; Maslauskaitė 2006). |

| 42 | For Castelli and Tencalla see especially the work of Mariusz Karpowicz, including (Karpowicz 2002, pp. 135–53; 2003). |

| 43 | On the chapel design see also (Žygas 1996, 2000; Mollisi 2013, pp. 29–31; Koutny-Jones 2015, pp. 173–75). On Pac’s involvement see (Jamski 2005a, p. 508). For Roman Counter-Reformation revivals of martyria, inlcuding for enshrining relics of Beati moderni, see (Noyes 2018, p. 295). |

| 44 | For the chapel programme see (Žygas 2000, pp. 33–35; Jamski 2005b, 2008; Czyż 2017); on the significance of the confessio see (Noyes 2018, pp. 180–81). For the confessio altar type in Poland in this period, see especially studies by Ryszard Mączyński, e.g., (Mączyński 2003, 2005). |

| 45 | See also Florence, ASF, MP, 4493, 430v. |

| 46 | For Sarmatist self-fashioning in period portraiture, including discussion of the distinguishing accoutrements and features, see (Grusiecki 2018; Guile 2018). |

| 47 | ARSI, Epistolae Externorum, vol. 36, fol. 32r-v. |

| 48 | See also Florence, ASF, MP 4493, fol. 492r, 608r-v, 609r-v and Guardaroba Medicea, n. 802 Guardaroba del taglio, 594. |

| 49 | See Florence, Archivio della Basilica di San Lorenzo, 73. |

| 50 | ASF, MP 4493, fol. 609r-v. |

| 51 | ASF, MP, 4493, fol. 431r. For the gifts exchanged between Grand Duke Cosimo and Hetman Pac see (Noyes forthcoming). |

| 52 | Echoing the recent study (Le Pouésard 2019). |

| 53 | For amber gifts to the Medici see (Piacenti 1966; King 2014, pp. 5–9). |

| 54 | On reliquaries’ architectural history see (Bucher 1976); on the resonances of the Kazimierz chapel in Vilnius see (Koutny-Jones 2015, pp. 173–75). |

| 55 | For an exploration of linkages between spolia and relics see (Elsner 2000). |

| 56 | For the Nordic-Baltic region and Siberia as sources of ivory in this period see (Rijkelijkhuizen 2009); for Medici ivory collections see (Schmidt 2008, 2012). For period mixed amber–ivory objects see e.g., (Gennaioli and Sframeli 2014, p. 224; King 2014, p. 6; Grusiecki 2017, pp. 10–12). |

| 57 | |

| 58 | See also ASF, MP, 4493, fol. 731r-v. |

| 59 | Ibid. |

| 60 | “Primary” or “first-class” relics were distinguished according to the Catholic church from “secondary” (objects a holy person used or touched) and “tertiary” (objects in physical contact with one of the former). See (Hahn 2013, pp. 8–9). Canon Law further distinguished between significant (insignes) relics, typically a saint’s entire body or a major portion thereof, and non-significant (non insignes) relics. A recent helpful theoretical overview of relics research with bibliography can be found (Kazan and Higham 2019). |

| 61 | Eighteenth-century inventory records for Pažaislis described a “large ebony reliquary with small silver shelves and three figurines on top, in which there are two Vella of S. Maria Magdalena de Pazzi, oil in an ampoule, a piece of gray habit.” Vilnius, Wroblewskis Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, f. 43-9919, “Pažaislio vienuolyno ir bažnyčios inventorius, sudarytas 1797,” 20–21. The reliquary’s facture corresponds to period examples produced in the Medici workshops. See also (Baniulytė 2010, p. 234). |

| 62 | See ASF, MP 1531 and GM 742, fol. 97. |

| 63 | ASF, MP, 4493, 435v. |

| 64 | On zibellini fertility talismans see (Sherrill 2006); for Cosimo III’s coronation regalia see (Langedijk 1971). |

| 65 | For an exposition of silver’s multifaceted discursive fashioning in relation to relics in this period see (Hills 2016, pp. 446–78). |

| 66 | On Lithuania’s pagan background see (Rowell 2014). |

| 67 | Echoing (Gupta 2014, pp. 13–14). |

References

Archival Sources

Rome, Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu (ARSI), Epistolae Externorum, vol. 36.Florence, Archivio di Stato Firenze (ASF), f. Mediceo del Principato: 1529–1753 (MP), 4489–4494; Guardaroba Medicea, n. 802 Guardaroba del taglio.Florence, Archivio della Basilica di San Lorenzo, 73.Vilnius, Wroblewskis Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, f. 43-9919, “Pažaislio vienuolyno ir bažnyčios inventorius, sudarytas 1797.”Primary Sources

- Baronio, Cesare. 1586. Martyrologium Romanum ad Nouam Kalendarii Rationem, et Ecclesiasticae Historiae Veritatem Restitutum. Gregorii 13. pont. max. Iussu Editum. Rome: ex typographia Dominici Basæ. [Google Scholar]

- Borovio, Filippo. 1644. Breue Racconto Del Martirio Santita Della Vita, Heroiche Virtu, E Miracoli Del Beato Giosafat Cunceuitio Arciuescouo Di Polocia Ruteno. Rome: Lodouico Grignani. [Google Scholar]

- Breve apostolicum. 1602. Breve apostolicum Clementis Papae VIII super festum S. Casimiri sub duplici ritu celebrandum in universo Poloniae Regno et Magno Ducatu Lituaniae cum lectionibus et orationibus propriis. Rome: Roman Catholic Church, 1602. [Google Scholar]

- di S. Antonio, Hilarione. 1629. Il Breve Compendio Della vita Morte, e Miracoli del Santissimo Prencipe Casimiro, figlio del Magno Casimiro re di Polonia, Riferita da Monsignore Zaccaria Ferrerio…. Naples: per Aegidio Longo. [Google Scholar]

- Długosz, Jan. 1615. Historia Polonica Ioannis Długossi seu Longini Canonici Cracovien in Tres Tomos Digesta. Dobromil: In officina Ioannis Szeligae. [Google Scholar]

- Długosz, Jan. 1981. Roczniki czyli Kroniki sławnego Królestwa Polskiego. Księga dziesiąta 1370–1405. Translated and Edited by Stanisław Gawęda, Danuta Turkowska, Maria Kowalczyk, Julia Mruk, Józef Garbacik, Zbigniew Perzanowski, and Krystyna Pieradzka. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Ercole, Domenico Antonio. 1687. Breue Compendio Della vita di S. Casimiro Confessore, Figliuolo del re di Polonia Cauata da Diuersi Autori. Rome: per Domenico Antonio Ercole. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri, Zaccaria. 1521a. Vita Beati Casimiri Confessoris: Ex Serenissimis Poloni[a]e Regibus & Magnis … Zacharia Ferrerio Vicentino Pontifice Gardien[se]: In Polonia[m] & Lituania[m]. Cracow: Iohannes Haller. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri, Zaccaria. 1521b. Oratio Legati Apostolici Habita Thorunij in Prussia ad Serenissimum Poloniae Regem contra Errores Fratris Martini Lutheri. Cracow: Iohannes Haller. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri, Zaccaria. 1523. De reformatione Ecclesiæ. Suasoria r.p.d. Zachariæ Ferrerij Vicentini pontificis Gardiensis. Venice: per Io. Antonium & fratres de Sabio. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri, Zaccaria. 1992. Zacharias Ferreri (1519–1521) et Nuntii Minores (1522–1553). Edited by Henryk Damian Wojtyska. Rome: Institutum Historicum Polonicum Romae, Fundatio Lanckoroński. [Google Scholar]

- Gerardi, Antonio. 1643. Sommaria Relatione Della Vita, E Miracoli Del Beato Martire Giosafat Cunceuitio Dell’Ordine Di S. Basilio Magno. Rome: Ludouico Grignani. [Google Scholar]

- Giovio, Paolo. 1574. Dialogo Dell’imprese Militari et Amorose di Monsignor Giouio Vescouo di Nocera. Lyon: appresso Guglielmo Rouillo. [Google Scholar]

- Guagnini, Alessandro. 1581. Sarmatiae Europeae Descriptio, Quae Regnum Poloniae, Lituaniam, Samogitiam, Russiam, Massouiam, Prussiam, Pomeraniam, Liuoniam, et Moschouiae, Tartariaeque Partem Complectitur. Spira: apud Bernardum Albinum. [Google Scholar]

- Lituanos, Michalos. 1615. Michalonis Lituani De moribus Tartarorum, Lituanorum et Moschorum, fragmina 10. Multiplici Historia Referta. Basel: apud Conradum Waldkirchium. [Google Scholar]

- Lituanos, Michalos. 1642. Quaedam ad lituaniam pertinentia, ex Fragmentis Michalonis Lituani. In Respvblica; siue, Status Regni Poloniæ, Litvaniæ, Prvssiæ, Livoniæ, etc. 1642. Leiden: Ex officina Elzeviriana, pp. 246–54. [Google Scholar]

- Miechowita, Maciej. 1521. Descriptio Sarmatiarum Asianae et Europianae et eorum quae in eis continentur. Cracow: Jan Haller. [Google Scholar]

- Officium S. Casimiri. 1603. Officium S. Casimiri Confessoris per totum Poloniae Regnum et magnum Lituaniae Ducatum Ex Decreto S. D. N. dementis VIII. Pont. Max. Rome: Apud Carolum Vulliettum. [Google Scholar]

- Petrauskas, Rimvydas. 2012. Litauen und der Deutsche Orden: Vom Feind zum Verbündeten. In Tannenberg—Grunwald—Žalgiris 1410: Krieg und Frieden im späten Mittelalter. Edited by Werner Paravicini, Rimvydas Petrauskas and Grischa Vercamer. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 237–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rosselli, Geronimo. 1642. Breve Compendio Della Vita, Morte, et Miracoli di S. Casimiro Dato in Luce da un Deuoto Servo del Santo. Palermo: Nicolò Bua & Michele Portanoua. [Google Scholar]

- Sacchini, Francesco. 1610a. Vita del beato Stanislao Kostka della Compagnia di Giesu. Composta dal P. Francesco Sacchini della medesima Compagnia. Rome: Bartholomeo Zannetti. [Google Scholar]

- Sacchini, Francesco. 1610b. Vita B. Stanislai Kostkae Poloni e Societatis Iesu, Auctore Francisco Sacchini Societatis eiusdem Sacerdote. Milan: Apud her. Petrimartyris Locarni, & Io. Bapt. Bidellium. [Google Scholar]

- Skarbek, Jan. 1684. Mars Gloriosus. Diuus Casimirus Poloniae Princeps, Pro Solemnitate Eiusdem Quarta Martij Celebrata, in Ecclesia Sanctissimi Saluatoris, Et Sancti Stanislai Nationis Polonae De Vrbe. Rome: Michaelis Herculis. [Google Scholar]

- Sobecki, Jan Kazimierz. 1674. Virtus Regia S. Casimiri Principis Poloniae Magni Ducis Lituaniae, in Ecclesia Sancti Stanislai Nationis Polonae a Ioanne Casimiro Sobecki Panegyrica Oratione Celebrata. Rome: Varesij. [Google Scholar]

- Stryjkowski, Maciej. 1582. Kronika Polska, Litewska, żmudzka i Wszystkiej Rusi (Chronicle of Poland, Lithuania, Samogitia and all of Ruthenia). Kaliningrad: Drukowano w Krolewcu: U Gerzego Osterbergera. [Google Scholar]

- Susza, Jakob Jan. 1665. Cursus Vitae, et Certamen Martyrij, B. Iosaphat Kunceuicij Archiepiscopi Polocensis. Rome: Varesij. [Google Scholar]

- Susza, Jakob Jan. 1666. Saulus et Paulus Ruthenae Vnionis Sanguine beati IOSAPHAT Transformatus. Rome: Varesij. [Google Scholar]

- Theatrum S. Casimiri. 1604. Theatrum S. Casimiri: In quo Ipsius Prosapia, vita, Miracula, et Illustris Pompa in Solemni Eiusdem Apotheoseos Instauratione, Vilnae Lithuaniae Metropoli, V. Id. Maij, anno Domini M.DC.IV. Instituta Graphice Proponuntur…. Vilnius: Operis typographicis Academiae Societatis Iesu. [Google Scholar]

- Wijuk Kojałowicz, Albert (Wojciech). 1650. Histoirae Lituanae pars prior: De rebus Lituanorum ante susceptam Christianam Religionem … Libri Novem. Gdansk: Sumptibus G. Försteri. [Google Scholar]

Secondary Sources

- Achermann, Hans-Jakob. 1981. Translationen heiliger Leiber als barockes Phänomen. Jahrbuch für Volkskunde 4: 101–11. [Google Scholar]

- Acton, Harold. 1988. The Last Medici. London: Cardinal, Sphere Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeteta, Letizia. 2016. Arte Transparente. La Talla del Cristal en el Renacimiento Milanés. Madrid: Prado Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Baniulytė, Aušra. 2003. Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės didikų Pacų kilmė iš Italijos: Tarp iliuzijos ir tikrovės. [The italian descent of Pacai, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania noblemen: Between illusion and reality]. In Dailė: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis 31. Istorinė Tikrovė ir Iliuzija: Lietuvos Dvasinės Kultūros šaltinių Tyrimai. Edited by Dalia Klajumienė. Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos, pp. 103–10. [Google Scholar]

- Baniulytė, Aušra. 2005a. Italai XVI–XVII a. Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės kasdieniame gyvenime. In Lietuvos etnologija/Lithuanian Ethnology. Edited by Auksuolė Čepaitienė. Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Baniulytė, Aušra. 2005b. Pacai ar Pazzi? Nauja Palemono legendos versija LDK raštijoje. In Istorijos Rašymo Horizontai, Senoji Lietuvos literatūra. Edited by Aušra Jurgutienė and Sigitas Narbutas. Vilnius: Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos institutas, pp. 140–66. [Google Scholar]

- Baniulytė, Aušra. 2007. I Pazzi di Lituania nella corrispondenza italiana del XVII secolo: Storia e onomastica. In Res Balticae: Miscellanea Italiana di Studi Baltistici. Livorno: Books & Company, pp. 127–44. [Google Scholar]

- Baniulytė, Aušra. 2009. The Pazzi Family in Lithuania: Myth and Politics in the European Court Society of the Early Modern Age. Medium Aevum Quotidianum 58: 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Baniulytė, Aušra. 2010. Šv. Marijos Magdalenos de’Pazzi kultas Lietuvos baroko kultūroje: Atvaizdai ir istorinė tikrovė. Darbai ir Dienos 53: 225–58. [Google Scholar]

- Baniulytė, Aušra. 2012. Italian Intrigue in the Baltics: Myth, Faith, and Politics in the Age of the Baroque. Journal of Early Modern History 16: 23–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Sheila. 2015. Christine de Lorraine and Medicine at the Medici Court. In Medici Women. The Making of a Dynasty in Grand Ducal Tuscany. Edited by Giovanna Benadusi and Judith C. Brown. Toronto: Centre for Renaissance and Reformation Studies, pp. 154–80. [Google Scholar]

- Baronas, Darius, and S. C. Rowell, eds. 2015. The Conversion of Lithuania. From Pagan Barbarians to the Late Medieval Christians. Vilnius: Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore. [Google Scholar]

- Barraclough, Eleanor Rosamund, Danielle Marie Cudmore, and Stefan Donecker, eds. 2016. Imagining the supernatural north. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press. [Google Scholar]

- Batizi, Zoltán. 2018. Mining in Medieval Hungary. In The Economy of Medieval Hungary. Edited by József Laszlovszky, Balázs Nagy, Péter Szabó and András Vadas. Leiden: Brill, pp. 166–81. [Google Scholar]

- Benay, Erin. 2020. Of Rhinos, Peppercorns and Saints: (Re)presenting India in Medici Florence. In Art, Mobility, and Exchange in Early Modern Tuscany and Eurasia. Edited by Francesco Freddolini and Marco Musillo. New York: Routledge, pp. 121–45. [Google Scholar]

- Blomkvist, Nils. 2005. The Discovery of the Baltic: The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (AD 1075–1225). Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, Barbara Drake, and Elisabeth Taburet-Delahaye, eds. 1996. Enamels of Limoges, 1100–1350. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Bouley, Bradford A. 2017. Pious Postmortems: Anatomy, Sanctity, and the Catholic Church in Early Modern Europe. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brahmer, Mieczysław. 1980. Powinowactwa Polsko-włoskie: Z Dziejów Wzajemnych Stosunków Kulturalnych. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. [Google Scholar]

- Brege, Brian. 2017. Renaissance Florentines in the Tropics: Brazil, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, and the Limits of Empire. In The New World in Early Modern Italy, 1492–1750. Edited by Elizabeth Horodowich and Lia Markey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 206–22. [Google Scholar]

- Brege, Brian. 2020. Making a New Prince: Tuscany, the Pasha of Aleppo, and the Dream of a New Levant. In Art, Mobility, and Exchange in Early Modern Tuscany and Eurasia. Edited by Francesco Freddolini and Marco Musillo. New York: Routledge, pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Briedis, Laimonas. 2008. Vilnius, City of Strangers. Vilnius: Baltos Lankos. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, Ashley Lynn. 2018. The Politics of Medicine at the Late Medici Court: The Recipe Collection of Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici (1667–1743). Ph.D. thesis, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, François. 1976. Micro-Architecture as the ‘Idea’ of Gothic Theory and Style. Gesta 15: 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugiani, Piero. 2007. From Innocent III to Today—Italian Interest in the Baltic. Journal of Baltic Studies 38: 255–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burman, Edward. 1989. Italian Dynasties: The Great Families of Italy from the Renaissance to the Present Day. Wellingborough and Northamptonshire: Equation. [Google Scholar]

- Caccamo, Domenico. 2010. Le Indie d’Europa: Polonia, Ucraina, Russia nella letteratura di viaggio e di esplorazione. In Roma, Venezia e l’Europa Centro-Orientale: Ricerche Sulla Prima età Moderna. Franco Angeli: Milano, pp. 352–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chojnicka, Krystyna. 2010. Romowe: Źródło Legendy O Rzymskim Rodowodzie Litwinów. In Vetera Novis Augere: Studia I Prace Dedykowane Profesorowi Wacławowi Uruszczakowi. Edited by Stanisław Grodziski, Dorota Malec, Anna Karabowicz Anna and Marek Stus. Krakow: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, Eric. 2016. Le Crociate del Nord: Il Baltico e la Frontiera Cattolica: 1100–1525. Bologna: Il mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Chynczewska-Hennel, Teresa. 2006. Nuncjusz I Król: Nuncjatura Maria Filonardiego W Rzeczypospolitej 1636–1643. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo “Neriton”. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Leah R. 2018. Collecting Art in the Italian Renaissance Court: Objects and Exchanges. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Codello, Aleksander. 1970. Hegemonia Paców na Litwie i ich wpływy w Rzeczypospolitej 1669–1674. Studia historyczne 13: 25–56. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, Clare. 2016. Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi: The Making of a Counter-Reformation Saint. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, Anthony. 1984–1985. On Byzantine Boxes. The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 42/43: 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Czapliński, Władysław. 1979. Pac Stefan. In Polski słownik biograficzny. Wroclaw: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, vol. 24, pp. 748–49. [Google Scholar]

- Czyż, Anna Sylwia. 2017. Kaplice św. Kazimierza i Niepokalanego Poczęcia Najświętszej Maryi Panny przy katedrze wileńskiej oczami karmelitanek bosych - nierozpoznane źródło z 1638 roku. Saeculum Christianum 24: 162–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Czyż, Anna Sylwia. 2018. Pamięć o poprzednikach i kłótnie z kapitułą, czyli o działalności biskupa Mikołaja Stefana Paca na rzecz skarbca katedry wileńskiej. Humanities and Social Sciences 23: 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Czyż, Anna Sylwia. 2020. The Symbolic and Propaganda Message of the Heraldic Programmes in Two 17th-Century Marriage Prints (Epithalamia) of the Pacas Family. Knygotyra 73: 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davies, Norman. 2013. Litva: The Rise and Fall of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: A Selection from Vanished Kingdoms. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Dilke, O. A. W. 1984. Geographical Perceptions of the North in Pomponius Mela and Ptolemy. Arctic 37: 347–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dini, Pietro U. 2010. ALILETOESCVR: Linguistica Baltica Delle Origini. Livorno: Books & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Dini, Pietro U. 2014. The Latin Theory and Vilnius Latinizers. In Prelude to Baltic Linguistics: Earliest Theories about Baltic Languages (16th Century). Leiden: Brill, pp. 45–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ditchfield, Simon. 1995. Liturgy, Sanctity, and History in Tridentine Italy: Pietro Maria Campi and the Preservation of the Particular. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ditchfield, Simon. 2007. Tridentine Worship and the Cult of Saints. In The Cambridge History of Christianity, vol. 6, Reform and Expansion, 1500–1600. Edited by R. Po-Chia Hsia. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 201–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ditchfield, Simon. 2009. Thinking with Saints: Sanctity and Society in the Early Modern World. Critical Inquiry 35: 552–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donecker, Stefan. 2010. The Lion, the Witch and the Walrus: Images of the Sorcerous North in the 16th and 17th Centuries. TRANS Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften 17. Available online: http://www.inst.at/trans/17Nr/4-5/4-5_donecker.htm (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Donecker, Stefan. 2016. Est vera India septemtrio: Re-imagining the Baltic in the age of discovery. In Re-forming Texts, Music, and Church Art in the Early Modern North. Edited by Tuomas Lehtonen and Linda Kaljundi. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 393–419. [Google Scholar]

- Donecker, Stefan. 2018. The Vagina nationum in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries: Envisioning the North as a Repository of Migrating Barbarians. In Visions of North in Premodern Europe. Edited by Dolly Jørgensen and Virginia Langum. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 307–28. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, Jaś. 2000. From the culture of spolia to the cult of relics: The Arch of Constantine and the genesis of late antique forms. Papers of the British School at Rome 68: 149–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkind, Alexander. 2011. Barrels of fur: Natural resources and the state in the long history of Russia. Journal of Eurasian Studies 2: 164–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flynn, Dennis, and Arturo Giráldez. 1995. Born with a ‘Silver Spoon’: The Origin of World Trade in 1571. Journal of World History 6: 201–21. [Google Scholar]

- Freddolini, Francesco. 2020. Francesco Paolsanti Indiano and His Early Seventeenth-Century Trade Between Florence and Goa. In Art, Mobility, and Exchange in Early Modern Tuscany and Eurasia. Edited by Francesco Freddolini and Marco Musillo. New York: Routledge, pp. 146–66. [Google Scholar]

- Frick, David. 2013. Kith, Kin, and Neighbors: Communities and Confessions in Seventeenth-Century Wilno. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Robert. 1993. After the Deluge: Poland-Lithuania and the Second Northern War, 1655–1660. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Robert. 2015. The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania, vol. I: The Making of the Polish-Lithuanian Union, 1385—1569. New York: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Galkus, Juozas. 2009. Lietuvos Vytis: Albumas. Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla. [Google Scholar]

- Gennaioli, Riccardo, and Maria Sframeli, eds. 2014. Sacri Splendori: Il Tesoro Della ‘Cappella Delle Reliquie’ in Palazzo Pitti. Livorno: Sillabe. [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi, Renato. 2012. Livorno e l’Atlantico: I commerci olandesi nel Mediterraneo del Seicento. Bari: Cacucci. [Google Scholar]

- Girkus, Romualdas, and Viktoras Lukoševičius. 2012. Europinė Sarmatija ankstyvojoje kartografijoje/Reflection of European Sarmatia in Early Cartography. Geodesy and Cartography 36: 123–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, Annamaria. 1997. The Grand Ducal Workshops at the Time of Ferdinando I and Cosimo II. In Treasures of Florence: The Medici Collection 1400–1700. Edited by Cristina Acidini Luchinat. Munich: Prestel, pp. 115–43. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, Annamaria. 2003. Torricelli, Giuseppe Antonio. Grove Art Online. Available online: https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000085746 (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Grabowska, Janina. 1971. The Diplomatic Career of Gdańsk Amber. Poland 8: 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Grusiecki, Tomasz. 2017. Foreign as Native: Baltic Amber in Florence. World Art 7: 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grusiecki, Tomasz. 2018. Uprooting Origins: Polish-Lithuanian Art and the Challenge of Pluralism. In Globalizing East European Art Histories: Past and Present. Edited by Beáta Hock and Anu Allas. New York: Routledge, pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Grusiecki, Tomasz. forthcoming. Sarmatia Revisited: Maps and the Making of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In Diversity and Difference in Poland-Lithuania and Its Successor States. Edited by Stanley Bill and Simon Lewis. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Guarini, Elena Fasano. 1984. COSIMO III de’ Medici, granduca di Toscana. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani 30. Available online: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/cosimo-iii-de-medici-granduca-di-toscana_(Dizionario-Biografico)/ (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Guérin, Sarah M. 2013. Meaningful Spectacles: Gothic Ivories Staging the Divine. Art Bulletin 95: 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, Giovanni Matteo. 2004. Novità e precisazioni sulla formazione artistica di Michele Arcangelo Palloni. In Artyści włoscy w Polsce XV–XVIII wiek. Edited by Joanna Pomorska. Warsaw: Wydawn "DiG", pp. 264–92. [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti, Giovanni Matteo. 2008. Additional Information about the Sources of Michele Arcangelo Palloni’s Artistic Language. Acta academiae artium Vilnensis 51: 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti, Giovanni Matteo. 2012. Il reliquairio di santa Maria Maddalena de’Pazzi a Vilnius e l’attività di Giovanni Comparini e Giuseppe Vanni per la corte di Toscana: Nuovi documenti. Bollettino della Accademia degli Euteleti della Città di San Miniato 79: 197–215. [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti, Giovanni Matteo. 2018. Firenze e Lituania. Un rapporto antico, un legame ritrovato. Essay for exhibition Firenze tra Rinascimento e Barocco. Dalle Collezioni d’Arte della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze e di Banca CR Firenze SpA. Vilnius. Available online: https://www.fondazionecrfirenze.it/la-collezione-di-fondazione-cr-firenze-in-mostra-a-vilnius/ (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Guile, Carolyn C. 2018. Reflections on the Politics of Portraiture in Early Modern Poland. In Globalizing East European Art Histories: Past and Present. Edited by Beáta Hock and Anu Allas. New York: Routledge, pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Pamila. 2014. The Relic State: St Francis Xavier and the Politics of Ritual in Portuguese India. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, Miguel Taín. 2018. A Medici Pilgrimage: The Devotional Journey of Cosimo III to Santiago De Compostela (1669). Turnout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, Cynthia. 2013. Strange Beauty: Issues in the Making and Meaning of Reliquaries. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdukiewicz, Leszek. 1982–1983. Pograbka (Pograbius) Andrzej. In Polski słownik biograficzny; Warsaw: Narodowy Instytut Audiowizualny. Available online: http://www.ipsb.nina.gov.pl/a/biografia/andrzej-pograbka (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Harmatta, János. 1996. The Scythians. In History of Humanity. Vol. 3: From the Seventh Century B.C. to the Seventh Century A.D. Edited by Joachim Herrmann and Erik Zürcher. New York: Routledge, pp. 181–82. [Google Scholar]

- Heinzelmann, Martin. 2002. Translation (von Reliquien). Lexikon des Mittelalters 8: 947–49. [Google Scholar]

- Herz, Alexandra. 1988. Cardinal Cesare Baronio’s Restoration of SS. Nereo ed Achilleo and S. Cesareo de’Appia. The Art Bulletin 70: 590–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, Helen. 2016. The Matter of Miracles: Neapolitan Baroque Architecture and Sanctity. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, Helen. 2020. Silver’s Eye: Naples, Excess, and Spanish Colonialism. In Nature and the Arts in Early Modern Naples. Edited by Frank Fehrenbach and Joris van Gastel. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs, Kerstin. 2007. Bernstein, das ’Preußische Gold’ in Kunst- und Naturalienkammern und Museen des 16.-20. Jahrhunderts. Ph.D. thesis, Humboldt.-Universität, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeester, Karin. 2016. Diamonds as global luxury commodity. In Luxury in Global Perspective: Objects and Practices, 1600–2000. Edited by Karin Hofmeester and Bernd-Stefan Grewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 55–90. [Google Scholar]

- Houben, Hubert, and Kristjan Toomaspoeg, eds. 2008. L’Ordine Teutonico tra Mediterraneo e Baltico: Incontri e scontri tra religioni, popoli e culture. Begegnungen und Konfrontationen zwischen Religionen, Völker und Kulturen. Galatina: Mario Congedo Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Jamski, Piotr. 2005a. The Building Stones of Zygmunt III Vasa in the Grand Duchyof Lithuania. In Actes du XIVe Colloque International de Glyptographie de Chambord ‘du 19–23 juillet 2004. Braine-le-Château: Ed. de la Taille d’Aulme, pp. 503–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jamski, Piotr. 2005b. Ołtarz relikwiarzowy w wileńskiej Kaplicy św. Kazimierza w pierwszej połowie XVII wieku. Barok. Historia-Literatura-Sztuka 12: 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Jamski, Piotr. 2008. Kaplica św. Kazimierza w Wilnie i jej twórcy. LDK Sakralinė Dailė: Atodangos ir Naujieji Kontekstai, Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis 51: 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Jobst, Kerstin S. 2012. Transnational and Trans-Denominational Aspects of the Veneration of Saint Josaphat Kuntsevych. Journal of Ukrainian Studies 37: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, Dolly. 2018. Beastly Belonging in the Premodern North. In Visions of North in Premodern Europe. Edited by Dolly Jørgensen and Virginia Langum. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, Dolly, and Virginia Langum, eds. 2018. Visions of North in Premodern Europe. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Jučas, Mečislovas. 1994. Théorie d’après laquelle la Lituanie et les nobles lituaniens sont originaires des Romains. In La via dell’ambra: Dal Baltico all’Alma Mater. Atti del Convegno italo-baltico, Bologna 18–20 settembre 1991. Edited by R. C. Lewanski. Bologna: Università degli Studi di Bologna, pp. 245–51. [Google Scholar]

- Karpowicz, Mariusz. 2002. Artisti Ticinesi in Polonia Nella Prima metà del Seicento. Lugano: Edizioni Ticino Management S. A. [Google Scholar]

- Karpowicz, Mariusz. 2003. Matteo Castello. L’architetto del Primo Barocco a Roma e in Polonia. Lugano: Edizioni Ticino Management. [Google Scholar]

- Kazan, Georges, and Tom Higham. 2019. Researching relics: New interdisciplinary approaches to the study of historic and religious objects. In Life and Cult of Cnut the Holy: The First Royal Saint of Denmark. Edited by Steffen Hope. Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag, pp. 142–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kiaupa, Zigmantas, Jurate Kiaupiene, and Albinas Kuncevicius. 2000. The History of Lithuania before 1795. Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History. [Google Scholar]

- King, Rachel. 2009a. The Shining Example of "Prussian Gold": Amber and Cross-Cultural Connections between Italy and the Baltic in the Early Modern Period. In Materiał rzeźby: Między techniką a semantyką. Edited by Aleksandra Lipińska. Wrocław: Wydawn Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego, pp. 456–70. [Google Scholar]

- King, Rachel. 2009b. Whale’s Sperm, Maiden’s Tears and Lynx’s Urine: Baltic Amber and the Fascination for It in Early Modern Italy. Ikonotheka 22: 168–79. [Google Scholar]

- King, Rachel. 2013a. Finding the Divine Falernian: Amber in Early Modern Italy. V&A Online Journal 5. Available online: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/journals/research-journal/issue-no.-5-2013/finding-the-divine-falernian-amber-in-early-modern-italy/ (accessed on 3 October 2021).

- King, Rachel. 2013b. The Beads with Which We Pray Are Made from It: Devotional Ambers in Early Modern Italy. In Religion and the Senses in Early Modern Europe. Edited by Christine Göttler and Wietse de Boer. Brill: Leiden, pp. 153–75. [Google Scholar]

- King, Rachel. 2014. Whose Amber? Changing Notions of Amber’s Geographical Origin. Ostblick 2: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Knoll, Paul. 1982. Jan Długosz, 1480–1980. The Polish Review 27: 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kotljarchuk, Andrej. 2006. In the Shadows of Poland and Russia: The Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Sweden in the European Crisis of the mid-17th Century. Huddinge: Södertörns University. [Google Scholar]

- Koutny-Jones, Aleksandra. 2015. Visual Cultures of Death in Central Europe: Contemplation and Commemoration in Early Modern Poland-Lithuania. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kriegseisen, Wojciech, Bartosz Wójcik, and Alex Shannon. 2016. Between State and Church: Confessional Relations from Reformation to Enlightenment: Poland, Lithuania, Germany, Netherlands. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Kudachinova, Chechesh. 2019. The Muscovite Silver Crusade: Power, Space, and Imagination in Early Modern Eurasia. Ab Imperio 4: 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulicka, Elżbieta. 1980. Legenda o rzymskim pochodzeniu Litwinów i jej stosunek do mitu sarmackiego. Przegląd historyczny 71: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Langedijk, Karla. 1971. A New Cigoli: The State Portrait of Cosimo I De’ Medici, and a Suggestion concerning the Cappella De’ Principi. The Burlington Magazine 113: 575–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lazure, Guy. 2007. Possessing the Sacred: Monarchy and Identity in Philip II’s Relic Collection at the Escorial. Renaissance Quarterly 60: 58–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le Pouésard, Emma. 2019. By the skin of its teeth: Walrus ivory, the artisan, and other bodies. Postmedieval 10: 316–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1982. The Way of the Masks. Translated by Sylvia Modelski. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Evonne. 1997. Reproduction in the ‘Cultic Era of Art’: Pierre Legros’s Stanislas Kostka. Representations 58: 88–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewanski, Riccardo Casimiro, ed. 1994. La via dell’Ambra. Dal Baltico All’Alma Mater. Atti Del Convegno Italico-Baltico. Bologna: Università degli Studi. [Google Scholar]

- Mączyński, Ryszard. 2003. Nowożytne Konfesje Polskie. Artystyczne Fory Gloryfikacji Grobów Świętych i BłogosłAwionych w Dawnej Rzeczypospolitej. Toruń: Wydawnictwo UMK. [Google Scholar]

- Mączyński, Ryszard. 2005. Konfesje—Ziemskie groby niebiańskich orędowników. Spotkania z Zabytkami XXIX: 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Markey, Lia. 2016. Imagining the Americas in Medici Florence. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Janet. 1986. Treasure of the Land of Darkness: The Fur Trade and Its Significance for Medieval Russia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martines, Lauro. 2004. April Blood: Florence and the Plot against the Medici. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maslauskaitė, Sigita. 2005. Neregėtas šventasis Kazimieras. Naujasis Židinys-Aidai 6: 233–37. [Google Scholar]

- Maslauskaitė, Sigita. 2006. Šv. Kazimiero relikvijos ir relikvijoriai. Acta academiae artium Vilnensis 41: 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Maslauskaitė-Mažylienė, Sigita. 2010. Šventojo Kazimiero atvaizdo istorija XVI–XVIII a. Vilnius: Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus. [Google Scholar]

- Maslauskaitė-Mažylienė, Sigita. 2013. Dzieje wizerunku św. Kazimierza od XVI do XVIII wieku. Między ikonografią a tekstem, z języka litewskiego przełożyła Katarzyna Korzeniewska. Vilnius: Publishing House of the Vilnius Art Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Maslauskaitė-Mažylienė, Sigita, ed. 2018. Masterpieces of the history of the veneration of St. Casimir: Lithuania – Italy. Vilnius: Bažnytinio paveldo muziejus. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrulevičiūtė, Daiva, ed. 2016. Lietuva-Italija: šimtmečių ryšiai. Vilnius: Išleido Nacionalinis muziejus Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valdovų rūmai. [Google Scholar]

- Modesti, Adelina. 2020. Women’s Patronage and Gendered Cultural Networks in Early Modern Europe: Vittoria della Rovere, Grand Duchess of Tuscany. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mollisi, Giorgio, ed. 2013. Gli artisti del lago di Lugano e del Mendrisiotto nel Granducato di Lituania (dal XVI al XVIII sec.). Lugano: Edizioni Ticino Management. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, William H. 1978. An Early French Ivory of the Virgin and Child. Museum Studies 9: 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Jason. 2010a. ‘Amsterdam is Standing on Norway,’ Part I: The Alchemy of Capital, Empire and Nature in the Diaspora of Silver, 1545–1648. Journal of Agrarian Change 10: 33–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Jason. 2010b. ‘Amsterdam is Standing on Norway’ Part II: The Global North Atlantic in the Ecological Revolution of the Long Seventeenth Century. Journal of Agrarian Change 10: 188–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Jason. 2010c. “This lofty mountain of silver could conquer the whole world”: Potosí and the Political Ecology of Underdevelopment, 1545–1800. Journal of Philosophical Economics 4: 58–103. [Google Scholar]

- Morawski, Paolo. 1989. ’Le ‘Indie d’Europa’. Tre schede per una ricerca in corso. Europa Orientalis 8: 301–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mottana, Annibale. 2006. Italian gemology during the Renaissance: A step toward modern mineralogy. In The Origins of Geology in Italy. Edited by Gian Battista Vai and W. Glen E. Caldwell. Boulder: Geological Society of America, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Alan, ed. 2001. Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier, 1150–1500. Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Alan, ed. 2009. The Clash of Cultures on the Medieval Baltic Frontier. Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Alan. 2010. The Saracens of the Baltic: Pagan and Christian Lithuanians in the Perception of English and French Crusaders to Late Medieval Prussia. Journal of Baltic Studies 41: 413–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musillo, Marco. 2020. The Russian Fata Morgana of Cosimo III: The Fluctuating Portraits of Kangxi between Florence and Beijing. In Art, Mobility, and Exchange in Early Modern Tuscany and Eurasia. Edited by Francesco Freddolini and Marco Musillo. New York: Routledge, pp. 167–86. [Google Scholar]

- Nef, John U. 1941. Silver Production in Central Europe, 1450–1618. Journal of Political Economy 49: 575–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzer, Susanne. 1993. Bernsteingeschenke in der preussischen Diplomatie des 17. Jahrhunderts. Jahrbuch Der Berliner Museen 35: 227–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, Thomas, and Roman Kovalev. 2004. The Furry 40′s. Packaging Pelts in Medieval Northern Europe. In States, Societies, Cultures, East and West. Essays in Honor of Jaroslaw Pelenski. Edited by Janusz Duzinkiewicz. New York: Ross, pp. 653–82. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowska, Natalia. 2014. High clergy and printers: Anti-Reformation polemic in the kingdom of Poland, 1520–36. Historical Research 87: 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, Ruth Sargent. 2018. Peter Paul Rubens and the Counter-Reformation crisis of the Beati moderni. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Noyes, Ruth Sargent. forthcoming. ‘The Polar Winds have driven me to the conquest of the Treasure in the form of the much-desired relic.’ (Re)moving relics and performing gift exchange between early modern Tuscany and Lithuania. In Gifts and Materiality: Gifts as Objects in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Edited by Gustavs Strenga and Lars Kjar. London: Bloomsbury.

- Orzeł, Joanna. 2010. Sarmatism as Europe’s Founding Myth. Polish Political Science Yearbook XXXIX: 149–57. [Google Scholar]

- Orzeł, Joanna. 2019. From imagination to political reality? The Grand Duchy of Lithuania as a successor of Rome in the early modern historiography (15th–18th centuries). Open Political Science 1: 170–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrow, Steven. 2009. The ‘Confessio’ in Post-Tridentine Rome. In Arte e committenza nel Lazio nell’età di Cesare Baronio. Edited by Patrizia Tosini. Rome: Gangemi, pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Panella, Antonio. 1917. Candidati italiani al trono polacco. I Medici. Rassegna Nazionale 16: 269–79. [Google Scholar]

- Papée, Fryderyk. 1939–1946. Długosz h. Wieniawa (Ioannes Dlugossius, Longinus) Jan. In Polski słownik biograficzny; Warsaw: Narodowy Instytut Audiowizualny. Available online: http://www.ipsb.nina.gov.pl/a/biografia/jan-dlugosz-h-wieniawa-1415-1480-kanonik-krakowski-historyk (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Piacenti, Kirsten Aschengreen. 1966. Due altari in ambra al Museo degli Argenti. Bolletino d’arte 51: 163–66. [Google Scholar]

- Platania, Gaetanio. 1992. Venimus, Vidimus Et Deus Vicit: Dai Sobieski Ai Wettin, La Diplomazia Pontificia Nella Polonia Di Fine Seicento. Cosenza: Periferia. [Google Scholar]

- Platania, Gaetanio. 2000. “Rzeczpospolita,” Europa E Santa Sede Tra Intese Ed Ostilità: Saggi Sulla Polonia Del Seicento. Viterbo: Sette Città. [Google Scholar]

- Platania, Gaetanio. 2011. Polonia e Curia Romana: Corrispondenza tra Giovanni III Sobieski, re di Polonia con Carlo Barberini protettore del Regno. Viterbo: Sette Città. [Google Scholar]

- Poole-Jones, Katherine. 2020. The Medici, Maritime Empire, and the Enduring Legacy of the Cavalieri Di Santo Stefano. In Florence in the Early Modern World: New Persepctives. Edited by Nicholas Scott Baker and Brian Maxson. New York: Routledge, pp. 156–86. [Google Scholar]

- Quirini-Popławska, Danuta. 1982. La corte di Toscana e la terza elezione in Polonia. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Prace Historyczne 71: 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Quirini-Popławska, Danuta. 1998. Dwór medycejski i Habsburgowie a trecia elecja w Polsce. Odrodzenie i Reformacja w Polsce 42: 121–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rabikauskas, Paulius, ed. 1989. La Cristianizzazione Della Lituania. Atti del Colloquio Internazionale di Storia Ecclesiastica in Occasione del 6 Centenario Della Lituania Cristiana (1387–1987). Roma, 24–26 Giugno 1987. Città del Vaticano: Libreria editrice vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Rachuba, Andrzej. 1979. Mikołaj Stefan Pac. In Polski Słownik Biograficzny. Wroclaw: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, vol. 14, pp. 738–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rijkelijkhuizen, Marloes. 2009. Whales, Walruses, and Elephants: Artisans in Ivory, Baleen, and Other Skeletal Materials in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Amsterdam. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 13: 409–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ronchi De Michelis, Laura. 2003. GUAGNINI, Alessandro. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani 60. Available online: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/alessandro-guagnini_(Dizionario-Biografico) (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Rowell, Stephen C. 2002. Lietuva-krikščonybės pylimas?: Vienos XV amžiaus ideologijos pasisavinimas. In Europos idėja Lietuvoje: Istorija ir dabartis. Edited by Darius Staliūnas. Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rowell, Stephen C. 2014. Lithuania Ascending: A Pagan Empire within East-Central Europe, 1295–1345. Cambridge: CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinson, Karen. 1975. Herodotus and the Scythians. Expedition Magazine 17: 16–20. Available online: http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/?p=2981 (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Rush, Alfred C. 1962. Spiritual Martyrdom in St. Gregory the Great. Theological Studies 23: 569–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, Alexa. 2014. Materia Meditandi: Haptic Perception and Some Parisian Ivories of the Virgin and Child, ca. 1300. Different Visions: A Journal of New Perspectives on Medieval Art 4: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sanger, Alice E. 2014. Art, Gender and Religious Devotion in Grand Ducal Tuscany. Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Eike D. 2008. Cardinal Ferdinando, Maria Maddalena of Austria, and the Early History of Ivory Sculptures at the Medici Court. Studies in the History of Art 70: 158–83. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Eike D. 2012. Das Elfenbein der Medici: Bildhauerarbeiten für den florentiner Hof. München: Hirmer. [Google Scholar]

- Schoonhoven, Erik. 2010. A Literary Invention: The Etruscan Myth in Early Renaissance Florence. Renaissance Studies 24: 459–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrill, Tawny. 2006. Fleas, Furs, and Fashions: Zibellini as Luxury Accessories of the Renaissance. In Medieval Clothing and Textiles. Edited by Robin Netherton and Gale R. Owen-Crocker. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, vol. 2, pp. 121–50. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Joseph M. 2020. To the Victor Go the Spoils: Christian Triumphalism, Cosimo I de’ Medici and the Order of Santo Stefano in Pisa. In Art, Mobility, and Exchange in Early Modern Tuscany and Eurasia. Edited by Francesco Freddolini and Marco Musillo. New York: Routledge, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli, Riccardo. 2019. Le Committenze Sacre Di Cosimo III De’ Medici: Episodi Poco Noti o Sconosciuti (1677–1723). Florence: Edifir Edizioni Firenze. [Google Scholar]

- Srodecki, Paul. 2015. Antemurale Christianitatis: Zur Genese der Bollwerksrhetorik im östlichen Mitteleuropa an der Schwelle vom Mittelalter zur Frühen Neuzeit. Husum: Matthiesen Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Stöve, Eckehart. 1996. FERRERI, Zaccaria. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani 46. Available online: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/zaccaria-ferreri_(Dizionario-Biografico)/ (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Ström, Helena Wangefelt, and Federico Barbierato. 2018. Omne malum ab Aquilone: Images of the Evil North in Early Modern Italy and their Impact on Cross-Religious Encounters. In Visions of North in Premodern Europe. Edited by Dolly Jørgensen and Virginia Langum. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 265–86. [Google Scholar]

- Suchocki, Jerzy. 1987. Geneza litewskiej legendy etnogenetycznej. Aspekty polityczne i narodowe. Zapiski Historyczne 52: 27–67. [Google Scholar]

- Tamm, Marek. 2009. A New World into Old Words: The Eastern Baltic Region and the Cultural Geography of Medieval Europe. In The Clash of Cultures on the Medieval Baltic Frontier. Edited by Alan V. Murray. Aldershot: Ashgate, pp. 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tamm, Marek, Linda Kaljundi, and Carsten Selch Jensen, eds. 2011. Crusading and Chronicle Writing on the Medieval Baltic Frontier: A Companion to the Chronicle of Henry of Livonia. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Tazzara, Corey. 2020a. Port of Trade or Commodity Market? Livorno and Cross-Cultural Trade in the Early Modern Mediterranean. Business History Review 94: 201–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazzara, Corey. 2020b. Disembedding the Market. Commerce, Competition, and the Free Port of 1676. In Art, Mobility, and Exchange in Early Modern Tuscany and Eurasia. Edited by Francesco Freddolini and Marco Musillo. New York: Routledge, pp. 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Teles e Cunha, João. 2001. Hunting Riches: Goa’s Gem Trade in the Early Modern Age. In The Portuguese, Indian Ocean and European Bridgeheads 1500–1800: Festschrift in Honour of Prof. K. S. Mathew. Edited by Pius Malekandathil and Jamal Mohammed. Tellicherry: Institute for Research in Social Sciences and Humanities of MESHAR, pp. 269–304. [Google Scholar]

- Trivellato, Francesca. 2000. From Livorno to Goa and Back: Merchant Networks and the Coral-Diamond Trade in the Early-Eighteenth Century. Portuguese Studies 16: 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Tutino, Stefania. 2013. ’For the Sake of the Truth of History and of the Catholic Doctrines’: History, Documents, and Dogma in Cesare Baronio’s Annales Ecclesiastici. Journal of Early Modern History 17: 125–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tygielski, Wojciech. 2015. Italians in Early Modern Poland: The Lost Opportunity for Modernization? Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, William. 2003. The Teutonic Knights: A Military History. St. Paul: MBI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Perkins, John Bryan. 1952. The Shrine of St. Peter and its Twelve Spiral Columns. Journal of Roman Studies XLII: 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wieland, Franz. 1906. Mensa und Confessio: Studien über den Altar der Altchristlichen Liturgie. Munich: J.J. Lentner, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, Larry. 1994. Inventing Eastern Europe. The Map of Civilization on the Mind of the Enlightenment. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Žygas, K. Paul. 1996. Dogma, Art and Politics: Roman Aspects of St. Casimir’s Chapel in Vilnius. Journal of Baltic Studies 27: 175–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žygas, K. Paul. 2000. The Spirit of Austerity and the Materials of Opulence: Architectural Sources of St. Casimir’s Chapel in Vilnius. Journal of Baltic Studies 31: 5–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Noyes, R.S. ‘Purest Bones, Sweet Remains, and Most Sacred Relics.’ Re-Fashioning St. Kazimierz Jagiellończyk (1458–84) as a Medieval Saint between Counter-Reformation Italy and Poland-Lithuania. Religions 2021, 12, 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111011

Noyes RS. ‘Purest Bones, Sweet Remains, and Most Sacred Relics.’ Re-Fashioning St. Kazimierz Jagiellończyk (1458–84) as a Medieval Saint between Counter-Reformation Italy and Poland-Lithuania. Religions. 2021; 12(11):1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111011

Chicago/Turabian StyleNoyes, Ruth Sargent. 2021. "‘Purest Bones, Sweet Remains, and Most Sacred Relics.’ Re-Fashioning St. Kazimierz Jagiellończyk (1458–84) as a Medieval Saint between Counter-Reformation Italy and Poland-Lithuania" Religions 12, no. 11: 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111011

APA StyleNoyes, R. S. (2021). ‘Purest Bones, Sweet Remains, and Most Sacred Relics.’ Re-Fashioning St. Kazimierz Jagiellończyk (1458–84) as a Medieval Saint between Counter-Reformation Italy and Poland-Lithuania. Religions, 12(11), 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111011