Encountering the Goddess in the Indian Himalaya: On the Contribution of Ethnographic Film to the Study of Religion

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background: In Search of a Question

It is a common belief in the hills that the soul or life of man consist of two parts. In the more Hinduised tracts the two elements are known as chitr and gupt—memory and speech.5 Gupt does not ordinarily leave the body until death, but chitr is of a wandering disposition, given to nocturnal adventures. It is he who leaves the body during sleep, and dreams are but the record of his adventures. With his return to the body, a dream ceases, although it may happen that he does not return at all.(Emerson n.d., fo. 867)

2.1. From Valley to Hilltop: Geography, History, and Culture in a Himalayan Hinterland

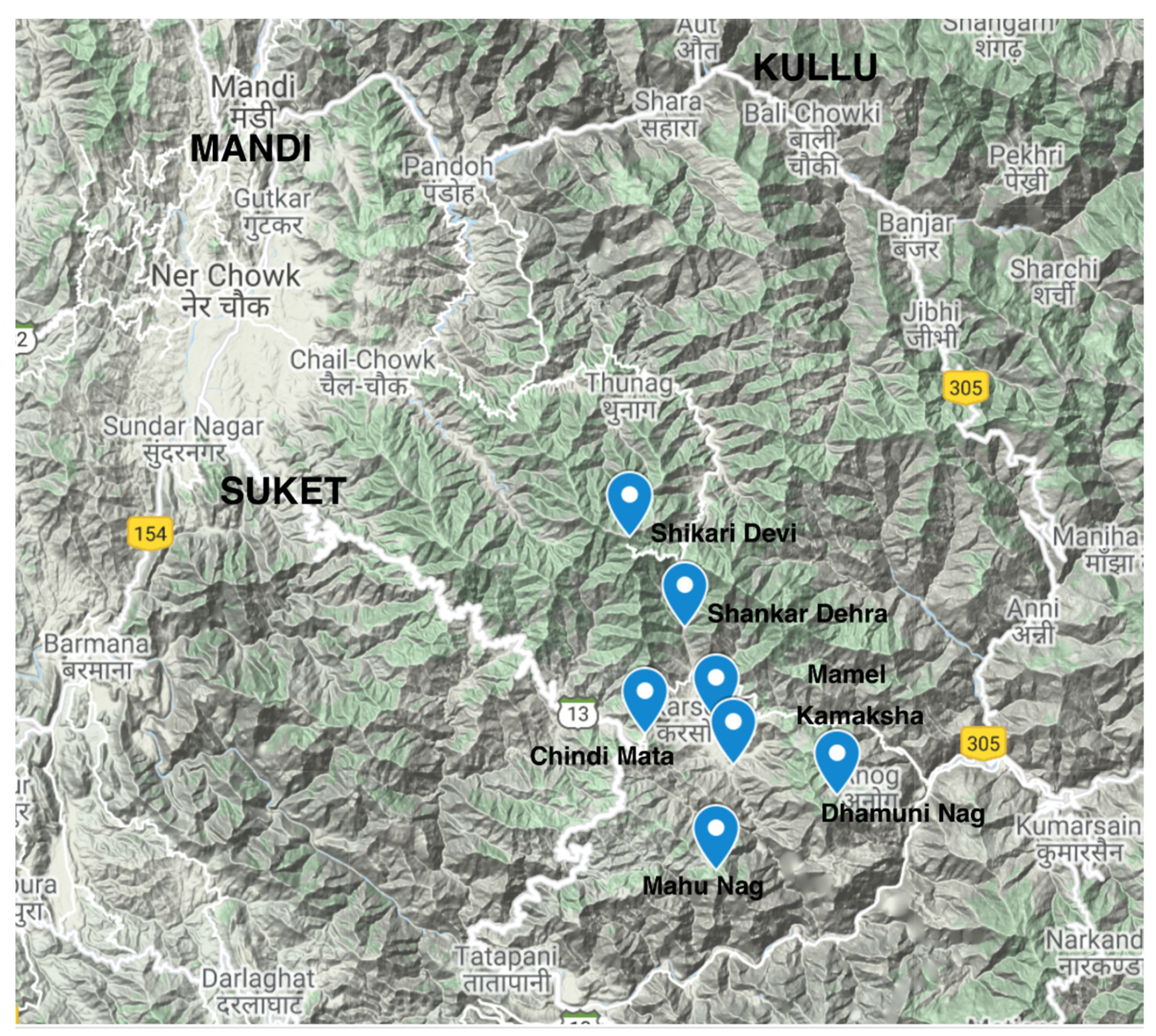

2.2. Village Gods, Regional Goddesses, and the Sacred Geography of Karsog

3. Encounters with the Goddess

3.1. Chindi (Caṇḍīka) Devi

Encounter 1: The Goddess as Exorcist

Jyoti/Ciṇḍī: Speak! What are you? (bol, kyā cīz hai tū?)Woman/Rākśas: (Mumbles).Priest: Why are you harassing this girl?Jyoti/Ciṇḍī (menacingly): Speak or be damned for a dozen years! [i.e., a very long time].Woman/Rākśas: (Cries).Jyoti/Ciṇḍī: Speak! What are you? Speak or I’ll curse you with the [combined] powers of Brahmā, Viṣṇu, and Śiv!Woman/Rākśas: (Mumbles and cries).Jyoti/Ciṇḍī: You won’t speak? Fine. I banish you for twelve years. Hark, Stand back! [casts a handful of rice from a plate next to him at the young woman’s face with force, she responds with shrill cries].

Jyoti/Ciṇḍī: Today you are taking this sum from me. It is recorded in my register for twelve years [i.e., “forever”].Driver: Yes, Mother.Jyoti/Ciṇḍī: Your brother took money to buy a bed, he still hasn’t repaid. Don’t forget to sort this.Driver (growing tense): Yes, Mother.Jyoti/Ciṇḍī: Remember, all your family history is known here. Don’t go looking here and there. Don’t visit other temples.Driver (stirred up and angry): Mother dear, I was dissatisfied! That’s why I went to other temples. But I never abandoned you! I came here first, Mother! I was here before and, look, here I am still!Jyoti/Ciṇḍī (sterner): Don’t go visit other temples. Don’t you go looking around!Driver: Yes, Mother. I’m your man (i.e., devoted follower), Mother (mein terā ādmī hun, mātā). You know this.Jyoti/Ciṇḍī: Now go.[Driver bows his head.]

3.2. Shikari (Śikārī) Devi

Encounter 2: The Goddess as Counselor

Wife/Supplicant: Mother, bless and protect my family.Husband/Śikārī: Why did you come here?Wife/Supplicant: Look at the baby, it needs help.Husband/Śikārī: You made a mistake. Why did you use a machine to cut its hair? We won’t allow that, neither will Kamru Nag.16Wife/Supplicant: How are we supposed to know these things? It’s the Dark Age (Kālī Yug), we don’t know anything.Husband/Śikārī (hissing strongly): It is very bad. Why did you do this?!Wife/Supplicant: We apologized already. Now, fix it!

Husband/Śikārī: Someone is cheating! He is drinking in secret. You have to catch him!Wife/Supplicant: I know. I tried. He won’t listen.Husband/Śikārī: If he doesn’t stop then you have to beat it out of him!Wife/Supplicant: He doesn’t listen, what can we do?

4. Epilogue: The Goddess Manifests

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For a detailed discussion of satī in the Rajput setting of North and Western India, see Moran (2019b, pp. 105–23). On satī in the area explored in this paper, see Section 3.2, below. |

| 2 | A couple of months later, we ultimately did find an alternative performance of the ritual that we were able to shoot (Harel and Moran 2018) and then analyze in a separate research article (Moran 2018). |

| 3 | For a useful introduction and discussion of the societal and phenomenological approaches towards religion, see (Pickering 1975; Proudfoot 1985), respectively. |

| 4 | For a lucid defense of religious experience as a viable analytical category that furthers the study of religion, see (Bush 2012). |

| 5 | It is unclear how Emerson arrived at these terminologically confusing definitions of “memory” and “speech”, which are better translated as “colorful image” (chitr) and “hidden/secret one” (gupt). |

| 6 | The pace of cultural change in the area is visibly slower than in areas with better connectivity (e.g., Kangra, Kullu). Women in Outer Seraj, for example, were expected to cover their heads on festive occasions until fairly recently; Brahmi women wore red scarves (dhātu), while others donned black (Bhatnagar 1998, p. 143). |

| 7 | Rice and maize are harvested in the kharīf season (September–October). Wheat is the main rabī crop (April–May). |

| 8 | The princess was buried alive in a wall, echoing a universal folk theme (Dundes 1996). For an analysis of the Chamba tradition, see Sharma (2016). |

| 9 | My thanks to Alexis Sanderson for references on this topic (email communication, December 2013). According to Sanderson, this is the farthest east that a specimen of the Kashmiri type has been reported, indicating the medieval floruit of Kashmiri artisanry and culture had extended well into the eastern hinterlands of present-day Himachal Pradesh. For similar specimens from Kashmir, see (Siudmak 2013, pp. 380–98, especially plate 178 on p. 388, which dates to the beginning of the third quarter of the eighth century). At over a meter high, the stone image in Mamel recalls the near life-size bronze Vaikuṇṭha in the Lakṣmīnārāyaṇa temple at Chamba, which has been assigned to the ninth century (Pal 1975, plates 84a-c). |

| 10 | In 1987, some 30 buffaloes were offered in sacrifice in the course of the Navaratra festival (Harnot 1991, p. 101). |

| 11 | |

| 12 | The cult of Ciṇḍī/Caṇḍīka is especially powerful in central Kinnaur (Emerson n.d., fo 763–764), but it is unclear whether the two goddesses share any affinities beyond their name. |

| 13 | |

| 14 | For the film footage corresponding to this section, see https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Hj18Av1XD3-VUGhyjvdmGsFkYpwrDVSK/view?usp=sharing. Accessed 18 November 2021. |

| 15 | For the film footage corresponding to this section, see https://drive.google.com/file/d/1l9niHSkM_CQvGm4wfcDmrzB6FoDV_D8u/view?usp=sharing. Accessed 18 November 2021. |

| 16 | The head of the family was, in fact, speaking on behalf of two deities: Śikārī Devī and Kāmrū Nāg. The latter is a powerful weather god, whose temple is located at a few hours’ march west of Shikari. |

| 17 | The transition from the powerful goddess who blesses the family’s rice grains to the familiar husband who is intimately aware of “the usual place” at home where they should be stored is telling of the continuum of mental states entailed in spirit possession in South Asia. For a salient example from South India, see (Handelman 1995). |

| 18 | A friend from Kullu, whose name shall be kept anonymous for the sake of privacy, often recounts how his father used to become “possessed” and threaten his wife every time she asked him to stop drinking. He had consequently lost all faith in the authenticity of those claiming to speak for the gods. |

| 19 | For a powerful example of spirit possession surfacing issues to do with incest, see (Lecomte-Tilouine 2009). |

| 20 | For the film footage corresponding to this section, see https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SeXAdDdEZp0n1Wcfo5UWgFS3z9V2Q-CP/view?usp=sharing. Accessed 18 November 2021. |

| 21 | A shepherd from the higher reaches explained to us that the “joginī”, as he called Shikari Devi, can communicate with every person in whatever manner that is possible (language, signs, etc.). On the sign language (chommā) of yoginīs, see (Hatley 2007). |

References

- Berreman, Gerald D. 1999. Hindus of the Himalayas: Ethnography and Change. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. First Published 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Berti, Daniela. 2001. La Parole des Dieux: Rituels de Possession en Himalaya Indien. Paris: CNRS Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Berti, Daniela. 2009. Divine Jurisdictions and Forms of Government in Himachal Pradesh. In Territory, Soil and Soceity in South Asia. Edited by Daniela Berti and Gilles Tarabout. New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 311–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar, Satyapal. 1998. History and Culture of Kullu. Kullu: Anupam Prakashan. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, Ram Prasad, Heinz Werner Wessler, and Claus Peter Zoller. 2014. Fairy Lore in the High Mountains of South Asia and the Hymn of the Garhwali ‘Daughter of the Hills’. Acta Orientalia 75: 79–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindra, Pushpa. 1982. Memorial Stones in Himachal. In Memorial Stones: A Study of their Origin, Significance, and Variety. Edited by S. Settar and Gunther D. Sontheimer. Dharwad: Institute of Indian Art History, pp. 175–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, Stephen B. 2012. Are Religious Experiences too Private to Study? The Journal of Religion 92: 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundes, Alan, ed. 1996. The Walled-Up Wife: A Casebook. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Herbert William. n.d. [circa 1930?]. A Study of Himalayan Religion and Folklore. London: British Library, Asian and African Collections.

- Erndl, Kathleen M. 1993. Victory to the Mother: The Hindu Goddess of Northwest India in Myth, Ritual, and Symbol. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flueckiger, Joyce B. 2015. “Who am I ... what significance do I have?”: Shifting Rituals, Receding Narratives, and Potential Change of the Goddess’ Identity in Gangamma Traditions of South India. Oral Tradition 29: 171–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halperin, Ehud. 2019. The Many Faces of a Himalayan Goddess: Hadimba, Her Devotees, and Religion in Rapid Change. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Handa, Om Chandra. 2001. Temple Architecture of the Western Himalaya: Wooden Temples. New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Handa, Om Chandra. 2004. Naga Cults and Traditions in the Western Himalaya. New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Handelman, Don. 1995. The Guises of the Goddess and the Transformation of the Male: Gangamma’s Visit to Tirupati, and the Continuum of Gender. In Syllables of Sky: Studies in South Indian Civilization. Edited by David Shulman and Velchuru Narayana Rao. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 283–337. [Google Scholar]

- Harel, Nadav. 2020. AVATARA. Tel Aviv: NoProcess Films. [Google Scholar]

- Harel, Nadav, and Arik Moran. 2018. CHIDRA. Tel Aviv: NoProcess Films. [Google Scholar]

- Harlan, Lindsey. 1992. Religion and Rajput Women: The Ethic of Protection in Contemporary Narratives. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, William. 1989. The Sacred Marriage of a Hindu Goddess. Bloomington: Indian University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harnot, S. R. 1991. Himachal ke Mandir aur usne Judii Lok-Kathaaen (Himachal Temples and their associated Folk Tales). Shimla: Minerva Book House. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison, John, and Jean-Philippe Vogel, eds. 1933. History of the Panjab Hill States; 2 vols. Lahore: Superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab.

- Hatley, Shaman. 2007. “The Brahmayᾱmalatantra and Early Saiva Cult of Yoginis”. Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Korom, Frank J. 2020. One Goddess, Two Goddesses, Three Goddesses More: Recent Studies of Hindu Feminine Divinities. International Journal of Hindu Studies 24: 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecomte-Tilouine, Marie. 2009. The Dhuni Jagar: Possession and kingship in Askot, Kumaon. In Bards and Mediums: History, Culture and Politics in the Central Himalayan Kingdoms. Edited by Marie Lecomte-Tilouine. Almora: Almora Book Depot, pp. 78–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Ioan M. 1971. Ecstatic Religion: A Study of Shamanism and Spirit Possession. London: Pelican. [Google Scholar]

- Luchesi, Brigitte. 2018. Divinizing ‘on demand’? Kanya pūjᾱ in Himachal Pradesh, North India. In Divinizing in South Asian Traditions. Edited by Diana Dimitrova and Tatiana Oranskaia. London: Routledge, pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, Arik. 2018. The Invisible Path of Karma in a Himalayan Purificatory Rite. Religions 9: 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moran, Arik. 2019a. God, King, and Subject: On the Development of Composite Political Cultures in the Western Himalaya, circa 1800–900. Journal of Asian Studies 78: 577–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, Arik. 2019b. Kingship and Polity on the Himalayan Borderland: Rajput Identity during the Early Colonial Encounter. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, Sur Das. 2012. An Unpublished Account of Kinnauri Folklore. European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 39: 9–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, Pratapaditya. 1975. Bronzes of Kashmir. Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt. [Google Scholar]

- Peres, Ofer. 2021. Who by Fire: Models of Ideal Femininity in Pre-Modern Tamil Literature. Religions of South Asia 13: 348–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, William S. F., ed. 1975. Durkheim on Religion. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot, Wayne. 1985. Religious Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Ursula. 2003. Negotiating the Divine: Temple Religion and Temple Politics in Contemporary Urban India. New Delhi: Manohar. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, William S. 1991. Mountain Goddess: Gender and Politics in a Himalayan Pilgrimage. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, William S. 2003. Divine Kingdoms in the Central Himalayas. In Sacred Landscape of the Himalaya. Edited by Niels Gutschow, Axel Michaels, Charles Ramble and Ernst Steinkellner. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, pp. 177–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, William S. 2009. God of Justice: Ritual Healing and Social Justice in the Central Himalaya. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Mahesh. 2016. State, Waterways and Patriarchy: The Western-Himalayan Legend of Walled-up Wife. Himalaya: The Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies 35: 102–17. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Miranda. 2006. Buddhist Goddesses of India. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, Caleb, Moumita Sen, and Hillary Rodrigues, eds. 2018. Nine Nights of the Goddess: The Navarᾱtri Festival of South Asia. Albany: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Jogishwar. 1989. Banks, Gods and Government: Institutional and informal credit structure in a remote and tribal Indian district (Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh) 1960–85. Stuttgart: Steiner-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Siudmak, John. 2013. The Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Ancient Kashmir and its Influences. Ledien: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, Peter. 1998. Travelling Gods and Government by Deity: An Ethnohistory of Power, Representation and Agency in West Himalayan Polity. Ph.D. thesis, Oxford University, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, Peter. 2003. Very Little Kingdoms: The Calendrical Order of West Himalayan Hindu Polity. In Sharing Sovereignty: The Little Kingdom in South Asia. Edited by Georg Berkemer and Margret Frenz. Berlin: Verlag, pp. 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, Giridhar. n.d. Shri Mahunag Mahatmya. Churag: Self Published.

- Thakur, Seema, and R. C. Bhatt. 2017. Village Gods and Goddesses of Kinnaur and their Moneylending System. European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 49: 88–101. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moran, A. Encountering the Goddess in the Indian Himalaya: On the Contribution of Ethnographic Film to the Study of Religion. Religions 2021, 12, 1021. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111021

Moran A. Encountering the Goddess in the Indian Himalaya: On the Contribution of Ethnographic Film to the Study of Religion. Religions. 2021; 12(11):1021. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111021

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoran, Arik. 2021. "Encountering the Goddess in the Indian Himalaya: On the Contribution of Ethnographic Film to the Study of Religion" Religions 12, no. 11: 1021. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111021

APA StyleMoran, A. (2021). Encountering the Goddess in the Indian Himalaya: On the Contribution of Ethnographic Film to the Study of Religion. Religions, 12(11), 1021. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111021