1. Introduction

The Changxi River Basin in the areas bordering Fujian and Zhejiang provinces in-cludes most of the areas of Fu’an福安, Jiaocheng蕉城, Pingnan屏南, Zhouning周宁, Shouning寿宁, Zherong柘荣, Fuding福鼎, and Xiapu霞浦 counties in Fujian福建 province and part of the areas of Qingyuan庆元 and Taishun泰顺 counties in Zhejiang浙江 province (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The area is typical of the southeast coast of China that is covered with many such small river basins. The whole river basin unfolds in a complete tree root and fan-shaped distribution. Only the south side is open to the East China Sea. The other sides are surrounded by mountains. The social economy and cultural development of the Changxi River Basin was thus partly closed and partly open. The early production technology and civilization in this area was basically imported from the outside through its estuaries. Through these estuaries also flowed the mineral resources, timber, and tea produced from this area to inland China and even to many parts of the world.

From the south of the Qiantang钱塘 River to the north of the Zhujiang珠江River, most of the areas are vertical and crosscut the Zhongshan landform, surrounded by mountains. The main courses of these mountain-enclosed rivers basically do not penetrate beyond the province. In other words, this area is defined instead by the distribution of small river basins. The direction of the main stream is basically northwest–southeast, flowing east or south into the East China Sea. In such a particular geographical environment, these areas are surrounded by mountains on the west, north and east sides. The vast sea serves as a barrier on the south or southeast side. In contexts where there were not domestic disturbances or foreign invasions, the imperial central government ordered the development of these small river basins, doing so much later than similar plans enacted throughout large river basins and across central China. At the beginning of such development, the ancient counties, provinces and cities set up by the central governments here were all near estuaries. It is clear that the central governments’ administration and control of the small river basins in these southeast coastal areas started from the estuaries. Hence, this “central-to-local pipeline” was first directed from the sea. The sea routes backtracked along the main river channels and the tributaries to the hinterlands of the river basins and then arrived at the river basin’s marginal areas. Therefore, the production, economic relations and trade in these small river basins were relatively simpler than that of other large river basins. The formation, development and evolution of architectural technology here was also relatively clear and easy for us to investigate and study.

Since the late 19th century, foreign scholars were the first to start systematic investigations and research on ancient Chinese architecture, among which the more representative ones are German scholars Ernst Boerschmann, Japanese scholars Sekino Tadashi, Ito Chutaand Tokiwa Osada. Although these scholars had different goals and methods of investigation, their research had all covered several provinces of China. Among them, architecture scholar Ito Chuta conducted two months-long expeditions along the Yangtze River Basin in China. The religious scholar Tokiwa Osada conducted several thematic expeditions in the 1920s on the origins of Buddhism in China and Chan temples. He arrived in Fujian in 1929 and made an in-depth investigation of three Chan temples, including Xuefeng雪峰 Chongsheng崇圣 temple in Minhou闽侯, Gushan鼓山 Yongquan涌泉 temple in Fuzhou福州, and Huangboshan黄檗山 Wanfo万佛 temple in Fuqing福清 (

Osada and Tadashi 1939, p. VI-69-120;

He 2013, pp. 91–112). Unfortunately, that expedition did not include the northeastern part of Fujian, which is not far from Fuzhou. There have been studies on small river basins in the mountainous areas of the southeast coast of China, as well architectural academics’ work on the architecture of certain river basins. For the former, Wu Songdi at the Center of Historical Geographical Studies of Fudan University systematically discussed the relationship between the economic development, industrial characteristics and geographical environment of the southeastern coastal areas from the south of Ningbo宁波 to the north of Chaoshan潮汕 (

Wu 1990). Ma Xueqiang’s team from the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences systematically studied and investigated the Oujiang瓯江 river basin, the largest river in the south of Zhejiang Province (

Ma 2016). In the 1980s and 1990s, Chen Zhihua of Tsinghua University used sociological and architectural methods to conduct research on vernacular architecture distributed in the Nanxi楠溪 river basin that is a tributary of the Oujiang River Basin, mainly on the planning of the villages and the type of vernacular architecture, such as residential houses, ancestral halls, and temples. The characteristics of the vernacular architecture, craftsmanship and village planning principles in this river basin are discussed clearly in this book (

Chen 1992,

2004). In the past two decades, the author’s team has conducted in-depth research on the Changxi River Basin’s timber covered bridges and vernacular architecture. They have organized and summarized a large amount of comprehensive information on local architecture styles, structural types, and construction techniques in several books (

Liu 2017;

Liu and Chen 2016;

Liu and Hu 2011;

Liu and Shen 2005).

For a while, there has been a dearth of research into the remains of Buddhist architecture in the entire Changxi Basin from the perspective of the river basin. Currently, most of the information that can be found is based on the statistics of the traditional administrative divisions of provinces, counties, townships, and other units. From the perspective of the river basin’s economy, social development is accompanied by the successive development of economic activities along estuaries, main streams and tributaries chronologically. Therefore, this study focuses on Fu’an, located on the main stream area of the basin in order to grasp the development of the early remains of Buddhist architecture in the Changxi basin. Since 2015, the author’s team has carried out interdisciplinary investigations and research with religious scholars on the Buddhist relics of Fu’an. At present, the remains of ancient buildings in Fu’an mainly include temples, palaces, temples, residential buildings, and bridges. Among them, the Buddhist temples are comparatively older and better preserved.

2. The Core of the Changxi River Basin—The Remains of Ancient Buddhist Buildings in Fu’an

2.1. The Formation of Fu’an Buddhist Temples

Buddhism was introduced to China through its Western Regions as early as the 1st century C.E., then becoming a revered faith in the Central Plains. Fujian, located in the southeast corner of the Chinese mainland, has a closed geographical environment surrounded by mountains on three sides and the sea on the other, delaying its development. Controversy surrounds the questions of when and where Buddhism arrived in Fujian. Most scholars believe that it was transmitted by land from the Central Plains to the south in the late 2nd century C.E. (

Wang 1997, pp. 1–4). Some scholars also put forward the theory that “Buddhism spread into China by sea” (

Wu and Zheng 1995). Regardless of the path of Buddhism’s spread in China, Buddhism, as a foreign religion, has experienced conflicts, integration and development with traditional Chinese culture, and gradually formed the system of Chinese Buddhist denominations in the Sui隋 and Tang唐 Dynasties, which mainly included eight schools: Tiantai Zong天台宗, Sanlun Zong 三论宗, Faxiang Zong 法相宗, Lv Zong 律宗, Huayan Zong 华严宗, Jingtu Zong净土宗, Mi Zong 密宗, and Chan Zong 禅宗, with the Tiantai Zong 天台宗, Huayan Zong 华严宗, and Chan Zong禅宗 schools having the most Chinese characteristics (

Yang 1995, p. 67). It is generally believed that Chan Zong was founded by Dharma 达摩 and inherited by Huike 慧可, Sengcan 僧璨, Daoxin 道信 and Hongren 弘忍. After the death of the fifth ancestor Hongren, Chan Zong was divided into two schools by his disciples: the Southern School of Chan, represented by Huineng 慧能 (639–713), and the Northern School of Chan, represented by Shenxiu 神秀 (606–706). The northern school of Chan was prevalent in the northern region, centered on the capitals of Chang’an长安 and Luoyang洛阳 in the Tang dynasty, and was worshipped by the ruling class. Therefore, Shenxiu and his disciple Puji 普寂 (651–739) once gained a high Buddhist status. Meanwhile, the southern school of Chan was reformed and developed by Huineng in the south of five ridges (Lingnan岭南), and its influence was increasing and spread throughout the south area. Later, his disciple Shenhui 神会 (684–758) went to the north area and had a long-term debate with the northern school of Chan. Finally, the Southern school of Chan won the debate and replaced the northern school of Chan as the mainstream of Chan Zong in the late Tang dynasty (

Yang 1995, pp. 157–77). Huineng’s disciples inherited and developed his theory of Chan, and created many new schools of Chan. In addition to Shenhui who created the Heze Zong 菏泽宗, there are other important inheritors, such as Nanyue Huairang南岳怀让 (677–744) and Qingyuan Xingsi 青原行思 (671–740), who preached in Hunan湖南 and Jiangxi 江西 and have significant influences on the later generations (

Yang 1995, pp. 195–96).

In the Sui and Tang Dynasties, various schools of Buddhism were popular to varying degrees in some places. In particular, with the strong rise and rapid development of Chan Zong, from around from the late of 8th century to the late of 9th century, the southern school of Chan formed many Dharma centers in China, many of which became the origin of various tradition of Chan Zong (

Yang 1995, p. 251). Among them, the most influential tradition are Hongzhou Zong 洪州宗founded by Mazu Daoyi马祖道一(709–788), the disciple of Nanyue Huairang, and Shitou Zong石头宗founded by Shitou Xiqian石头希迁 (700–790), the disciple of Qingyuan Xingsi. Mazu Daoyi once went to Jianyang建阳 (now Jianyang District, Nanping City) to preach for a short time in the early Tianbao天宝 period of the Tang dynasty (around 742 C.E.) and received several disciples from Fujian. After that, Mazu Daoyi left Fujian and went to Jiangxi, where he taught disciples in Linchuan临川 (now Linchuan County, Jiangxi Province) and Hongzhou洪州 (now Nanchang City, Jiangxi Province). According to historical records, Mazu Daoyi has more than 139 disciples, including some from Fujian, such as Baizhang Huaihai 百丈怀海 (750–814, from Changle长乐) and Dazhu Huihai大珠慧海 (from Jianzhou 建州), and the regional scope of his disciples’ missionary work covered the vast region of China (

Yang 1995, p. 266). Although Daoyi and his disciples from Fujian did not preach Dharma in Fujian for a long time, the Chan Zong still has a lasting impact on Fujian Buddhism. There were many Fujian monks go to Jiangxi and Hunan to worship the Dharma and return to preach (

Wang 1997, p. 85). For example, Huangbo Xiyun黄檗希运 (?–855), a disciple of Baizhang Huaihai, went to Hongzhou to worship the Dharma after becoming a monk in Huangbo Moutain黄檗山, which was in his hometown, Fuzhou福州. Later, Xuefeng Yicun雪峰义存 (822–908), the fifth-generation inheritor of Shitou Zong石头宗, was from Nan’an南安, Quanzhou泉州. He was respected by the local governor at that time, and established Xuefeng temple on Xianggu Moutain of Fuzhou in 870 C.E. His disciples also successively created Yunmen Zong云门宗 and Fayan Zong法眼宗in the Chan School, and the temple later became an important Chan temple in the south of the Yangtze River (

Yang 1995, pp. 320–21). The emergence of local representative Chan masters and the establishment of Chan temples in Fujian indicated the popularity and development of the Chan School in Fujian at that time. Due to Buddhism being prosperous among the society and his great influence, Yicun was known as the famous figure of the Chan School in the late Tang dynasty. He had 56 disciples, 20 of whom preached Dharma in Fujian, and the footprints of other disciples also spread throughout most parts of China (

Wang 1997, p. 129). In this background, a large number of Chan temples were erected in the 9th century, although it is difficult to find the initial temples they erected today. However, most of the Chan temples were founded under their influence and within this context.

According to the Sanshanzhi Records 三山志, Qishan Yuan栖善院 Temple, founded in 849 C.E., is one of the earliest Buddhist temples in Fu’an with a known date. In the following hundred years of development, up to the Five Dynasties period (907–960), there were more than 30 temples erected in Fu’an alone. From the perspective of the spread and development of Chan Buddhism in this area, most Buddhist temples were Chan temples, most of which were built by local clans who “donated their houses as temples.” For example, the genealogy of the Ruan阮 Clan in Chenliu陈留, Shuyang枢洋 Village, and Tantou潭头 Town, Fu’an recorded that the ancestors of the Ruan family laid a foundation in Longyan龙岩 in 869 C.E. After serving as a resident for a few years, tigers caused calamities and alarm. The clan ancestor suspected that this showed the existence of the Buddha’s spirit, so he returned to his residence, and transformed the building into a Buddhist temple. This is a relatively early record of the formation of Buddhist temples in the Changxi River Basin (

Lan 2021, p. 97).

2.2. Remains of Fu’an Buddhist Temple

Early Chan Buddhism advocated only building Dharma halls rather than grand Buddhist halls. The Dharma hall was the most important building in an early temple. It had the functions of meditation and lectures and was also called the Chan hall. Unfortunately, investigation has not revealed any Buddhist temples with Chan halls left from the Tang Dynasty in the Changxi River Basin. According to the statistics in the Sanshanzhi Records quoted by Bucolic Fu’an, it was found that there were 138 temples in Fu’an alone from the 12th to 13th Century (

Liu and Chen 2016, p. 260). Many of them are preserved, such as Shifeng狮峰Temple, the Sanbao三宝Temple, the Xingyun兴云Temple, and more.

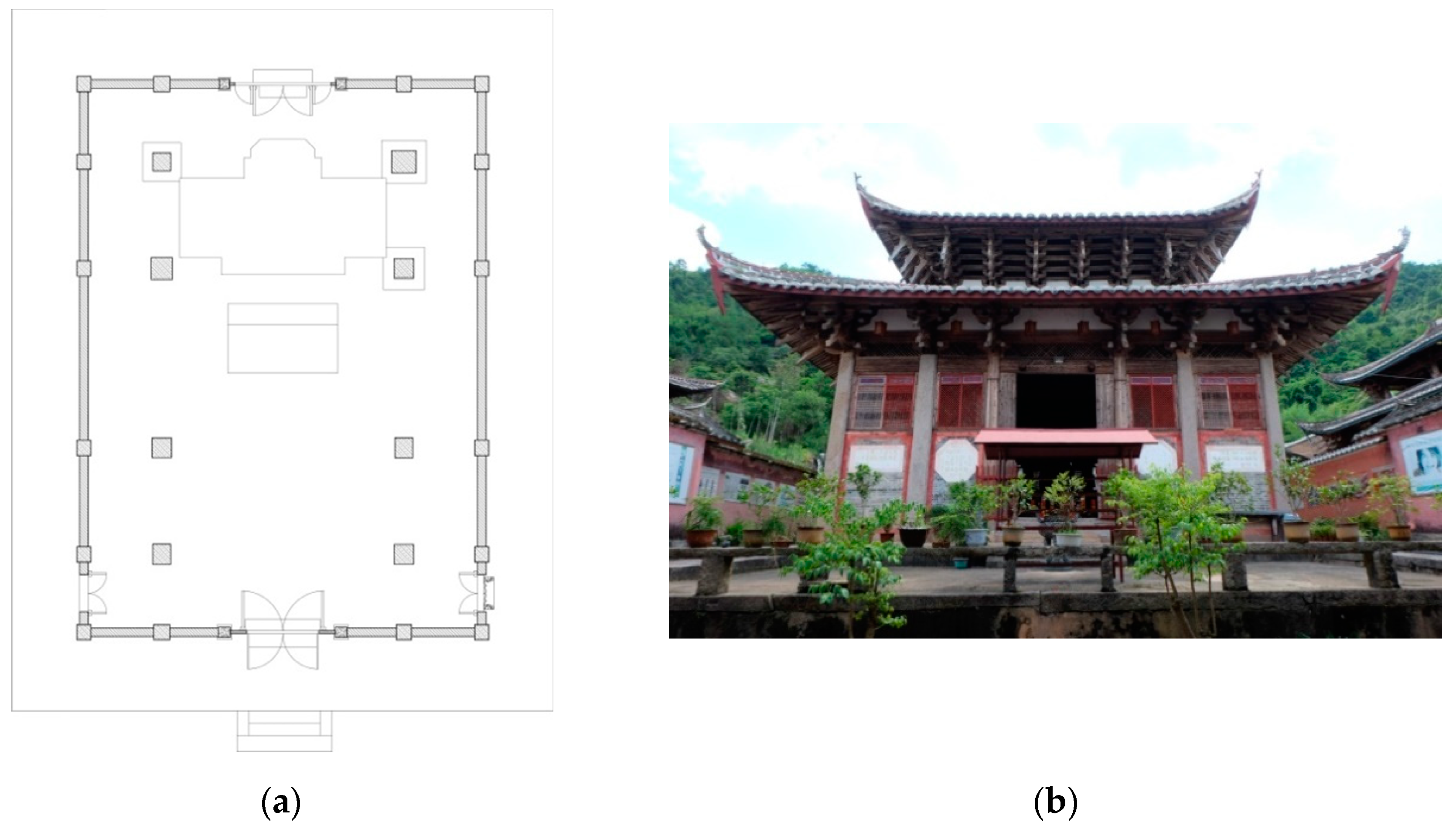

Shifeng Temple is located at the foot of Shifeng狮峰Peak in Xibing溪柄 Town, Fu’an. It was founded in 892 C.E. and has been rebuilt many times since. Today, the oldest building in the temple is the main hall, which was rebuilt in 1612 C.E. It has a width of 11.75 m with three bays and a depth of 16.20 m with five bays. The floor plan is a longitudinal rectangle, and the maximum height of the building is 14.24 m. The main hall has a Xieshan歇山 roof with double eaves. The main load-bearing pillars are stone with a square section except for the gate’s pillars that are made of wood. There are 28 pillars in total, including 24 stone pillars and 4 wooden pillars (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Sanbao Temple is located in Fu’an County. It was first built in the Song Dynasty as a school and renovated as a Buddhist temple in the Yuan Dynasty. It was rebuilt many times in the Ming and Qing dynasties. The main hall was rebuilt in 1733 C.E. It has a width of three bays measuring 11.21 m and a depth of four bays measuring 15.98 m. The plan is a rectangle with the longitudinal axis in the direction of depth. The main hall has a Xieshan roof with double eaves. The 22 pillars in total are made of stone. The section of the eight internal pillars is square-shaped. The body of the pillars has grooves, and some inscriptions are faintly visible. (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

Xingyun Temple, located in Rongtou榕头Village, Xibing溪柄 Town, was founded during 1098~1100 C.E. The main hall of the temple was built in about 1170 C.E. and was originally named Rulai (from the Buddhist term “Tathagata”) Hall如来殿. It was rebuilt in 1776 C.E. and has a width of five bays measuring 14.4 m and has a depth of six bays measuring 13.0 m. The middle bay along its width is 5.54 m. It has a single Xieshan eave and an almost square plane. There are 37 pillars in total in the temple. The four inner pillars in the center are the eight-petal or pumpkin-shaped circular stone pillars, relics from the beginning of the Southern Song Dynasty. The inner pillars in the center are 3.14 m in height and about 50 cm in diameter. Notches are cut in three directions in the capitals of the pillars. The body and the foot of the pillars are an integral whole in stone and there is no plinth. The pillars are clearly tapered at both ends. There are two identical stone pillars which have been found discarded outside the hall. Thus, it can be presumed that, originally, the temple had at least six stone pillars and that only four were used when the hall was rebuilt in the Qing Dynasty (

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

In addition to the above Buddhist temples, there are still many Buddhist temples in Fu’an that were built in the Tang and Song Dynasties. However, most of the halls in the temples have been rebuilt in modern times and their historical features have been changed completely. Only early stone pillars, stone grooves, stone foundations, and other architectural parts remain. For example, Bao’en报恩Temple, near Xingyun Temple, built from 1098 to 1100 C.E., has at least four round grooved pillars from the Song Dynasty (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). The Suoquan锁泉 Temple in Shouyang首洋Village, Xiaoyang晓阳Town, founded in 1099 C.E., also has four original pillars from the Song Dynasty in the main hall. Xingqing兴庆 Temple, founded in 968 C.E. in Panxi 蟠溪Village, Xitan溪潭 Town, previously retained its six original Song Dynasty pillars. In the new hall in 2014, regretfully, only four petal-shaped stone pillars were retained. The other two were left for display.

Several remarkable regional characteristics can be summarized on the basis of the existing Buddhist temple halls in Fu’an built from the 9th to 12th centuries:

Most Buddhist temples built hundreds or more than a thousand years ago retain their rectangular plans despite reconstruction or expansion in subsequent dynasties. Most of their parts and members have been replaced except for a few stone components and base elements that are not easily damaged or not easily replaced. Hence, very few original components remain that can reflect the original appearance assumed by these structures in the Tang and Song dynasties.

Stone pillars are commonly used as vertical load-bearing components. The petal-shaped corrugated eight-segment stone pillars commonly utilized in the 12th century still serve as the inner pillars in the middle of these Buddhist temples. At the same time, square stone pillars or wooden pillars were used by later generations to support extensions of the structures. The petal-shaped corrugated stone pillar (also called “segment pillars” in the Yingzao Fashi营造法式 (

Li 1933, p. 206) can be used to identify the age of the temples. There are many petal-shaped corrugated stone pillar relics in South China, and most of them were made in the Song Dynasty, such as the stone pillars of the main hall of Luohan Yuan罗汉院 in Suzhou and for the Kaiyuan Monastery开元寺 in Chaozhou潮州. Wood is not as durable as stone, and consequently, petal-shaped corrugated wooden pillars are not as well preserved. The only remaining case is the four petal-shaped, eight-segment corrugated stone pillars in the main hall of the Baoguo Monastery in Ningbo. The petal-shaped corrugated stone pillars are very common in the Changxi River Basin and can been seen in almost all the Buddhist temples. Most of them are petal-shaped corrugated stone pillars of eight segments, tapered at both ends. The petal-shaped corrugated stone pillars in one Buddhist temple are usually all the same size, about 3~4 m tall with a diameter of about 450~700 mm. The diameter-to-height ratio is about 1/6~1/8, which is less than the ratio of normal wooden pillars, making the stone pillars seem sturdy and solid by comparison.

Combining the characteristics of the plan and the structural frame, the evolution of most Buddhist temples from single-bay to three-bay or five-bay structures can be clearly seen. For example, in a three-bay temple, the middle bay is significantly wider than the adjacent bays. The ratio of the width of the middle bay to that of the adjacent bays is usually over two. Furthermore, the maximum middle bay width in these structures can reach 7.1 m, much more than the upper limit of 18 chi尺 (6 m) that is the maximum width for middle bays of main hall specified in the Song Dynasty Yingzao Fashi. The extremely large middle bay is rare in folk houses of the same period or later. Therefore, the extremely large middle bay is a significant indication that single-bay halls in Buddhist temples initially functioned to enclose an internal space.

3. The Restoration of the Early Forms of the Buddhist Halls in the Changxi River Basin

Existing investigations reveal that most of the temples remaining in the Changxi River Basin were rebuilt in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Their planes are nearly square, or they are rectangular, three or five bays wide, and three or five bays in deep. Their roof is often a single or double Xieshan roof, and its structure is based on local practice in Fujian since the Ming Dynasty. The few Buddhist temples that can be traced back to the Tang and Song dynasties can only be verified from remaining components. There are only the petal-shaped corrugated stone pillars of four or eight segments that were left from the Song Dynasty. From the perspective of the traditional Chinese concept of fengshui风水, the site selection and orientation of ancient Buddhist temples were generally strictly considered by founders at the beginning of construction, and the inheritors of the temple also remained devout to such principles. If there is no disaster during later periods of operation, the previous decision is considered to have been correct. There is a tradition of rebuilding on the original site of construction as well. Clearly, Buddhist temples created by predecessors were destroyed in future generations in the course of natural disasters or man-made disasters. Most of the components have disappeared, and only stone pillars, stone beams, and other stone components survive. This shows how stone components serve as a symbol of longevity in Buddhist temples. However, at the same time, the preservation and use of these finely selected and exquisitely crafted stone pillars donated by predecessors in the reconstruction of the temples by later generations undoubtedly demonstrates respect and the continuation of the history of temple construction. Therefore, in the above-mentioned cases, when the Buddhist temples were rebuilt during the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Song Dynasty stone pillars were used. However, just as a “stratum” becomes disturbed in archaeology, subsequent generations rebuilt the Buddhist temple on top of the relics of the Song Dynasty. The degree of such interventions on the original structure cannot be completely ascertained, so it is difficult to reveal the “original state” of buildings through current research. Although there are not a few Song Dynasty stone pillars in Fu’an Buddhist temples, the original arrangement of stone pillars has been possibly retained only in the Shifeng Temple Hall and Sanbao Temple Hall, based on an examination of the base site only. The remaining stone pillars in other temples are either inadequate or they have been moved. Therefore, it is difficult to use these remains to restore the appearance of the Song Dynasty Buddhist Temple. Here, we only make a speculative restoration based on relevant references.

3.1. The Single-Bay Hall

In a main hall of a temple, if the remaining six pillars in three rows or the eight pillars in four rows are regarded as eave pillars, the hall can be restored to a single-bay structure, extending multiple bays in depth. Although this pattern is not common, there are remains around the Changxi River Basin. For example, the Zushi祖师Ancestor Hall of West Mingshanshi名山室 located on the hillside of Gaogai高盖 Mountain in Yongtai永泰 County, Fujian Province, was built at the entrance of a mountainside cave and was founded in 1103 C.E. (

Figure 12). The hall is a single bay in width and two bays in depth with a single Xieshan roof. The six eave pillars are all petal-shaped corrugated stone pillars arranged in three rows. Although the structure has been repaired by later generations, it still follows the Song system and is a rare single-bay hall relic of the Song Dynasty. Although the Zushi祖师Ancestor Hall is not huge and is limited by the size of the cave, the structure proved that a single-bay width, multi-bay depth hall with a Xieshan roof is completely feasible.

There also are similar single-bay Buddhist temple remains found in archaeological sites, for example, the hall of Guoxing国兴 Temple built in 1011 C.E. in the Song Dynasty located on Taimu 太姥Mountain in Fuding福鼎. (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14) The main hall of Guoxing Temple is one bay in width and three bays in depth. The eight stone pillars are arranged in four rows. The pillars stand on the original position except for one that is lost. Although Guoxing Temple is located in a mountain col, the area for construction is spacious. The main hall should not have been restricted by the site when it was initially built. Therefore, the plan pattern of plan should have been one of the choices popular at that time (

Gao et al. 2021, pp. 7–11).

The main hall of Guoxing Temple is the only excavated site built in the Song Dynasty so far. Similar cases of this pattern of single bay in width and multiple bays in depth can be found in early murals and other paintings. For example, the pattern can be found in the Hui Yinguo Scripture, painted in the Nara Period (710–794), collected in the Nara National Museum, Japan. (

Figure 15) The Hui Yinguo Scripture绘因果经 is a picture book of the Past and Present Yinguo Scripture过去现在因果经 translated by Gunabhadra求那跋陀罗, who was an Indian monk preaching in the southeastern China during the 5th century. Similarly, a gate tower and a scene of construction of a Buddhist temple, both of single-bay in width and three-bay in depth, can be seen in Mogao莫高 Grottoes murals in Dunhuang敦煌 painted in the 8th century, which indicates that the single-bay pattern had already appeared in the Tang and Song Dynasties (

Figure 16).

3.2. The Tansformation from Single Bay to Three Bays

From the perspective of roof structures, a single-bay hall with three or four rows of pillars of the same height forming a rectangular plan can have either been a Xuanshan悬山or a Xieshan歇山 roof. When it comes to a Xuanshan roof, there are two possibilities: one is that the roof ridge is set in accordance with the direction of the depth, placing the entrance at the gable side. This can be found in very early times in the wooden structures of South China. It is derived from the “long houses” of matriarchal clans in the Neolithic Age. This practice later spread to Japan, and there are still remnants of such construction today. The other second possibility is that the roof ridge is set in the direction of the width of the hall. As a result, it was likely to be eroded by rain and damaged. Xieshan roofs, on the other hand, have slopes on all four sides, with the four eaves and four original pillar rows of the same height thus best suiting this form of roof. Thus, whether from the perspective of functionality or the requirements of ritual, the Xieshan roof was undoubtedly a better choice.

With the popularity and development of Chan Buddhism, the small single-bay Buddhist Hall developed and spread in the Changxi River Basin, gradually becoming the central building type for Buddhist temples in the 12th century. Obviously, the narrow indoor space formed by a single bay could no longer meet the requirements of Buddhist activities. Therefore, there were two main possibilities for expansion based on the foundation of the original single-bay hall.

Firstly, a line of eave pillars could be added on both sides and the roof extended. This is even common in the folk houses in Zhejiang and Fujian nowadays. The museum in Zhouning周宁 County, located in the upper reaches of the Changxi River Basin, houses a ceramic barn built in the 12th century with a hall of this type on its roof (

Figure 17). This kind of roof extension is relatively easy to build. Only the width of the hall is increased, and the depth stays the same. The whole plan thus transforms to nearly become a square.

The second possibility is to add eave pillars around the Buddhist hall consisting of a single bay in width and covered by a Xieshan roof. This forms a porch around the structure and a total width of three bays. The plan is still a longitudinal rectangle. Typical cases, such as the existing Shifeng Temple and Sanbao Temple, were rebuilt in the style of double-eave Xieshan roofs in the later generations. Another example is the Chen Taiwei 陈太尉Palace in Luoyuan罗源at the southern end of the Changxi River Basin (

Figure 18). It was built in 1239 C.E. and rebuilt many times subsequently. Its main hall is now three bays in width and six bays in depth. According to the shape and structure of the components, it is presumed that the original structure of the Song Dynasty consisted of a single bay in the middle forming its width and the first two bays in depth, and the rest was added by later generations. The expansion of the Chen Taiwei Palace in both width and depth caused the double-eave Xieshan roof to take on a somewhat weird shape (

Zhang 1999, pp. 67–68).

The main structure of the single-bay hall with a Xuanshan or Xieshan roof was not changed by the above two types of expansion (

Figure 19). However, when the original single bay width is expanded to three bays and the original roof structure is changed to fit three bays, the roof structure is undoubtedly changed. It is found through the investigation into the remains of the temples in the Changxi River Basin that there have been temples of three bays in width with single-eave Xieshan roofs built from the 10th to 14th centuries.

The transitional roof seems to be a temporary rather than a permanent structure and an intermediate product of the change from the Xuanshan to Xieshan roof. Although there are not many remains in the Changxi River Basin, from the perspective of technological evolution, it is reasonable to infer that the rectangular plan of the Buddhist hall with a single bay in width and three bays in depth with the longitudinal axis in the depth direction changed to a square plan with three bays in both width and depth. Such a path of change seems possible. The rectangular plan has been expanded into a square plan by adding two sides. Later reconstructions are often completed based on the square plan. The roof structure also has been improved and the single-eave Xieshan roof has prevailed. The remains of this type of Buddhist temple can be found in the South of the Yangtze River area, but it is not common in the Changxi River Basin.

4. The Reasons for the Evolution of Buddhist Halls in Changxi River Basin

The development of Buddhist temples in the Changxi River Basin began in the 9th century C.E. Now, after more than 1000 years of developments, there are still dozens of Buddhist temples that were founded during that era. Although most of this Buddhist architecture has been greatly changed due to reconstruction in previous dynasties, the appearance of Buddhist temples in various historical stages in the Changxi River Basin can still be analyzed and appreciated through the study of several sites and relics. As mentioned above, from the 9th to the 12th century C.E., Buddhist temples with widths composed of wide single bays and depths that extended across several bays prevailed in the Changxi River Basin. These plans were composed of longitudinal rectangular planes. Since the 14th century, these single-bay Buddhist halls were often transformed into larger Buddhist temples encompassing three or five bays in width. The direct reason for this evolution was to achieve larger indoor spaces. However, in terms of the larger history of Buddhist architecture, this expansion from small Buddhist halls into medium Buddhist temples was accompanied by the enrichment of spiritual space through developments such as Chan teachings and rituals.

In the early days of Chan Buddhism, monks lived in seclusion and traveled to learn. Later, they gradually settled in groups and set up fixed places for preaching. At the end of the 8th century, the Chan master Baizhang百丈created the rules of Chan Buddhism and proposed regulations for construction that set forth the requirement to build only Dharma halls rather than Buddha halls in temples. These rules and regulations were followed and observed by the inheritors of the tradition of Chan Buddhism. Later, from the 10th to 13th century, Chan Buddhism spread widely and became prosperous in South China. More and more Chan Buddhist temples were erected, and their scale was gradually enlarged. The rules and regulations of Chan Buddhism then gradually changed. The Buddhist halls, as the places for Buddhist faith, became more important than the Dharma hall (

Zhang 2002, pp. 72, 73). Thus, it was erected as the main hall of a temple in the 13th century. The Buddhist halls with three or five bays in width thus became mainstream. Under the layout rule of “Galan Seven Halls伽蓝七堂” that matured and took shape at the end of 13th Century, the Buddhist hall became the core of a temple and has expanded continually in subsequent times.

On the other hand, the doctrine of Chan has also constantly evolved with the passage of time. The original “non-written” oral teachings were subsequently written down, read, and taught. The original meditation ritual has become a part of daily life. The worship of the single Buddha of Sakyamuni释迦牟尼 has been changed to include the worship of multiple Buddhas. Such changes have brought about a series of changes in the space of the temple, such as the Dharma hall gradually becoming the lecture hall, and the function of the main hall has become an important space for rituals in Chan temples. In short, larger spaces became necessary.

It is worth noting that this change in Buddhist architecture caused by the development of Buddhist doctrines and rituals is reflected not only in the Changxi River Basin but also in the South of the Yangtze River region and other surrounding areas. As mentioned concerning Buddhist halls with square plans and with three bays in width and a single-eave Xieshan roofs in the south of the Yangtze River from the 10th to 13th century, most of such temples have been rebuilt or renovated during later dynasties, such as the main hall of Hualin 华林 Temple and Baoguo 保国 Temple (

Zhang 2012, pp. 188, 204), Yanfu 延福 Temple, and Zhenru 真如 Temple. These temples were all expanded with a porch around them based on the original structure, forming five bays in width with a double-eave Xieshan roof (

Figure 20). There are several reasons behind these expansions. One is to meet the new requirements of the space in the main halls for later generations. The other is the pursuit of a more magnificent and solemn space for worship, which may have been caused by the increasing worship of Buddha statues in the process of an increasing focus on laity.

5. Conclusions

Buddhist halls with a single bay in width and two or three bays in depth were popular in the Changxi River Basin from the 9th to the 13th centuries C.E. The roofs were usually supported by three or four rows of the petal-shaped corrugated stone pillars. The plan was a longitudinal rectangle, and the roof was a single-eave Xieshan歇山 roof. After the 13th century C.E., due to practical and symbolic needs, many temples were expanded by adding a porch around the original structures. The double-eave Xieshan roof was thus formed, and a few of them remain today.

Therefore, the following are concluded based on the above analysis:

The single-bay Buddhist hall in the Changxi River Basin was either a small-scale Buddhist Hall at the time of the implementation of the rule to build Dharma Halls and not Buddhist Halls, or it was the form of an early era Dharma Hall. The Buddhist hall became important in a temple in the 10th century. At that time, the traditional regulations on the construction of Chan Buddhist temples had been broken or developed. In 13th Century, the development of Chan Buddhism reached its peak, and its rules were popularized. Then, the main hall of temples of three or five bays in width were built by either demolishing the old temples on the original site and rebuilding a new one or by expanding the old temples.

The closed geographical environment of the Changxi River Basin has long been far away from the central or regional government center, allowing local Buddhism to develop more spontaneously and be influenced by local clans and believers. Therefore, there was a more conservative development of Buddhist architecture. The changes to the structure of the Chan temples were not as drastic as in the surrounding areas. The more ancient forms still exist in this area. The rectangular plan of the temples where the longitudinal axis is in the depth direction driven by the single bay in width remains to this day.

This study is an initial examination of single-bay Buddhist temples and their evolution in the Changxi River Basin through an investigation into these temple’s remains. It provides new references and academic support for the study of ancient Chinese Buddhist architecture and for the protection of the heritage in South China. More in-depth discussions on the techniques and evolution of the single-bay Buddhist temple will be carried out based on this study. This will include work regarding the roof forms, beam frames, and the direction of the Xuanshan roof of single-bay Buddhist temples. Through such research, we can better appreciate the significance of the Buddhist temples built in the Changxi River Basin from the 10th to 13th century.