Change and Continuity in Quaker Rhetoric after 1660 †

Abstract

1. Introduction

First, concerning the word thou or thee, which all those which are their Priests and Teachers knows, that thouis the proper word to one particular person, and is so all along the Scriptures throughout to any one, without respect of persons; yea to God himselfe; and the word you is the proper word to more then one, but not to one; and so it is all along the Scriptures throughout.

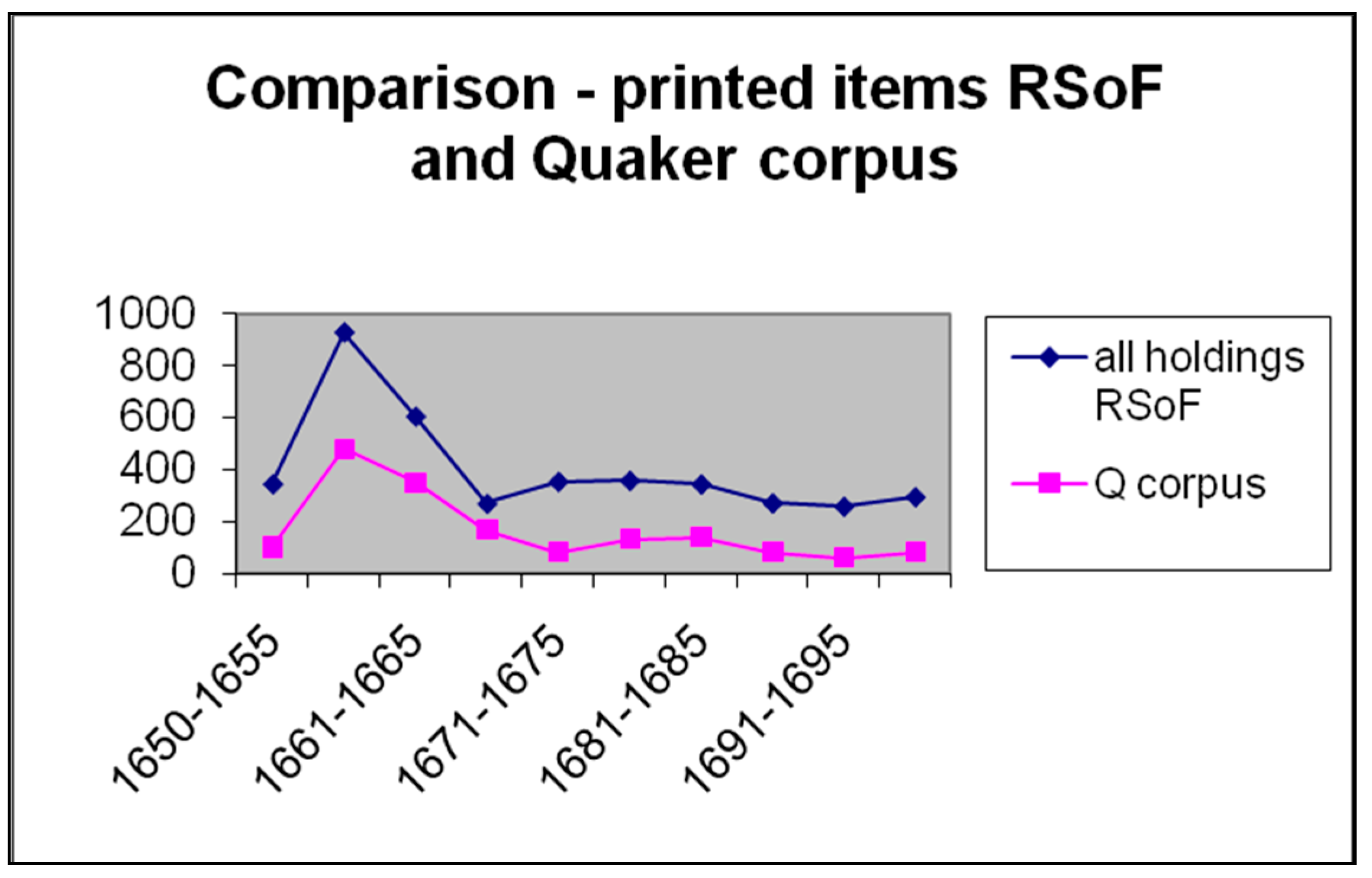

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Prophetic Discourse

[Prophesy] has the illocutionary2 force of a prediction with an additional, particularly authoritative model of achievement. The latter has to do with the authority of an oracle … of God or of divine revelation. The speaker presupposes that he has good reasons for the belief to the point of certitude.

- (1)

- God will smite you with shame and contempt so that you shall become a reproach to all that fears him. The day of the Lord shall come upon you as pain upon a woman in travel; and that light within, which you have a much derided and cried against, shall be kindled as a fire in your bowels. (Ambrose Rigge 1659).

- (2)

- God the righteous judge will render unto the wicked according to his works, then shall the goods which ye heaped together by violence and oppression, torment you … who now do spend your time in ungodliness, and do make your hearts as adamant, and harden your fore-heads as brass against the Lord, who hath given you a day to repent in. (John Rouse 1656).

- (3)

- What do you [conventional Christians] profess? Do you profess the life of Christ and cannot cease from sin, but plead for it term of life, as some of you do, and positively maintain. Is this your profession? Then wois your portion ye hypocrites, professing one life, and living another. (Richard Bradly 1660).

- (4)

- O! that you would once come to hear & obey the Voice of the Lord, and his threatning more Judgment and greater Calamity yet to come upon this City and Nation, if speedily you do not Repent, and turn to God, from all your Transgressions and horrible Abominations … Be ye all assured, that the Judgments come and threatned are not intended or sent where they come, that any should sleight or disregard them but seriously to consider them as so many Warnings from God, to the Wicked, for them to beware and take heed how they continue any longer in Sin, Rebellion and hard Heartedness against the Lord, lest sudden Destruction come upon you, that you will not be able to escape or flee from. (James Parke 1692)

A reduction in the stridency of tone … the Quaker movement changed from being one of the most radical of the sects … and became an introverted body, primarily concerned with its own internal life.

3.2. Distinctive Quaker Lexical Terms

- Words for divinity;

- Belief in “that of God”;

- Worship concepts;

- Action and exhortation.

- (5)

- Praises to the Lord our God over all, who is adding to his Church daily, such as shall be saved; therefore ye Children of the Light and of the Day of God’s Love, keep your Lamps trimmed, and furnished with the heavenly Oil, that you may enter in with the Bridegroom into the marriage Chamber, when the foolish are shut out. (Theophila Townsend 1690)

- (6)

- This … have I written unto you in true Love to your Souls, not knowing at present whether ever I may see your Faces, yea or nay; so bidding you farewel, I rest, who am a true Lover of your Souls, but do hate that persecuting spirit by which you have been led. (John Browne 1678)

- (7)

- And now in the sence of the springings up of the love of God in my soule, do I call unto all you males and females, who have been convinced, and have believed the truth as it is in Jesus and have been put to flight, either in the winter season or on the sabbath day, and have erred and gone astray from the way of the Lord. (John Danks 1680)

- wait for answers the question “who?” or “what?” (line 2)

- wait in answers the question “how?” or “where?” (lines 3–5)

- wait to + infinitive verb answers the question “why?” (line 7)

- wait [up]on seems to indicate the sense of giving service (lines 8–9)

4. A View Froma Quaker Adversary

There is not any thing in the Quakers Method of deluding which doth more tend to the insnaring of unwary Souls than their asserting their false, Antichristian, and Anti-Scriptural Tenets, under Scripture-Words and Phrases, and in those very Terms wherein are expressed the Truths of God; while in the mean time they mean nothing less than their true import, and what People (who are not well acquainted with their Tenets) suppose them to mean. By this Artifice they beget a good Opinion of themselves and Errours with too many, and by degrees so vitiate their Principles that in a short time they are prepared to embrace the grossest errors bare-faced.

5. Polemic Texts and Treatises

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

Primary Sources Quoted

Richard Bradly. This is for all you Inhabitants of Whitewell. 1660.John Browne. In the EleaventhMoneth, on the Nineth Day. 1678.John and Elizabeth Danks and John Furly. The Captives returne, or The Testimony of John Danks. 1680.James Parke. A Call in the Universal Spirit of Christ Jesus. 1692.Ambrose Rigge. To all the Hireling Priests in England. 1659.John Rouse. A Warning to the Inhabitants of Barbadoes.1656.Theophila Townsend. An Epistle of Tender Love to all Friends. 1690.Secondary Sources

- Allen, Richard C. 2018. Living as a Quaker during the Second Period. In The Quakers 1656–1723, the Evolution of an Alternative Community. Edited by Richard C. Allen and Rosemary Moore. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, pp. 76–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ambler, Rex. 2007. Truth of the Heart. London: Quaker Books, pp. 150–71. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, Hugh, and Arthur Roberts. 2004. Early Quaker Writings, 2nd ed. Wallingford: Pendle Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Richard. 1998. Let your Words Be Few, 2nd ed. London: Quaker Home Service. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, Douglas. 1993. Representativeness in Corpus Design. In Literary and Linguistic Computing 8: 243–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, William C. 1955. The Beginnings of Quakerism, 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Clenenden, Ray. 2003. Textlinguistics and Prophecy in the Book of the Twelve. Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 46: 385–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, Jackson. 1956. Seventeenth Century Quaker Style. Modern Language Association of America 71: 725–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandelion, Pink, Douglas Gwyn, and Tim Peat. 1998. Heaven on Earth: Quakers and the Second Coming. Birmingham: Curlew Productions and Woodbrooke College. [Google Scholar]

- Faldo, John. 1673. A Key to the Quakers Usurped, and (to Most) Unintelligible Phrases. London. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, Catie. 2017. Quakers. In The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern English Literature and Religion. Edited by Andrew Hiscock and Helen Wilcox. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, Michael. 2009. Preaching the Inward Light. Texas: Baylor University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Ian. 2000. Print and Protestantism in Early Modern England. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Gwyn, Douglas. 1986. Apocalypse of the Word: The Life and Message of George Fox. Richmond: Friends United Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, David. 1992. "The Fiery Tryal of their Infallible Examination": Self-control in the regulation of Quaker publishing. In Censorship and the Control of Print—in England and France 1660-1910. Edited by Robin Myers and David Hall. Winchester: St. Pauls Bibliographies, pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, T. Edmund. 1928. Quaker Language. Journal of the Friends Historical Society 15: 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ingle, Larry. 1987. From Mysticism to Radicalism: Recent Historiography of Quaker Beginnings. Quaker History 76: 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Rufus M. 1921. The Later Periods of Quakerism. London: Macmillan, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Keeble, Nigel. 1995. The Politic and the Polite in Quaker Prose: the case of William Penn. In The Emergence of Quaker Writing: Dissenting Literature in Seventeenth-Century England. Edited by Thomas Corns and David Loewenstein. London: Frank Cass, pp. 112–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood, Rachel. 2019. Stand Still in The Light: What Conceptual Metaphor Research can tell us about Quaker Theology. Religions 10: 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnen, Thomas. 2008. Tracing Directives through Text and Time: Towards a methodology of a corpus-based diachronic speech-act analysis. In Speech Acts in the History of English. Edited by Andreas Jucker and Irma Taavitsainen. Pragmatics & Beyond New Series. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. viii, 176, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littleboy, Anna. 1921. A History of the Friends’ Reference Library, with Notes on Early Printers and Printing in the Society of Friends. London: Society of Friends. [Google Scholar]

- Mace, Jane. 2020. Passion and Partings: the Dying Sayings of Early Quakers. York: Quacks Books. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, David. 2009. Accusations of Blasphemy in English Anti-Quaker Polemic, c1660–1701. Quaker Studies 14: 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEnery, Tony, Richard Xiao, and Yukio Tono. 2006. Corpus-based Language Studies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Charles. 2002. English Corpus Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge: CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Rosemary. 2000. The Light in Their Consciences. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Rosemary. 2018. Quaker Expressions of Belief in the Lifetime of George Fox. In The Quakers: the Evolution of an Alternative Community. Edited by Richard Allen and Rosemary Moore. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, Thomas. 1982. “Defying the Powers and Tempering the Spirit”. A Review of Quaker Control over their Publications 1672-1689. The Journal of Ecclesiastical History 33: 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, James. 1655. A Shield of the Truth. London. [Google Scholar]

- Peace Testimony. 1660. A Declaration from the Harmless and Innocent People of God. Called Quakers. Also Known as the Peace Testimony. Available online: www.qhpress.org/quakerpages/qwhp/dec1660.htm (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- Penington, Isaac. 1661. Concerning the Worship of the Living God. London: Proquest. [Google Scholar]

- Roads, Judith. 2014. Incantational and Catechetical Style in Early Quaker Prose Writings. Quaker Studies 19: 172–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roads, Judith. 2015. The Distinctiveness of Quaker Prose, 1650–1699: A Corpus-Based Enquiry. Ph.D. thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Michael. 2008. WordSmith Tools Version 5. Liverpool: Lexical Analysis Software. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, John R. 1976. A Classification of Illocutionary Acts. Language in Society 5: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, John R., and Daniel Vanderveken. 2009. Foundations of Illocutionary Logic. Cambridge: CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, John. 1991. Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Nigel. 1989. Perfection Proclaimed: Language and Literature in English Radical Religion, 1640–1660. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, Marvin A. 1996. Isaiah 1-39: With An Introduction to Prophetic Literature. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Definition of collocation: the habitual juxtaposition of a particular word or phrase with another word or words with a frequency greater than chance. (OED). |

| 2 | Illocutionary: an intended underlying sense. |

| Number of Texts | Approx. Number of Different Authors | Total Word Size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q50s (1650–1659) | 49 | 45 | 197,260 |

| Q60s (1660–1672) | 57 | 52 | 221,660 |

| Q-post1673 (1673–1699) | 75 | 73 | 226,630 |

| Q50s & Q60s: Addressees | Q-Post1673: Addressees | |

|---|---|---|

| Government (Parliament or Monarch) | 45% | 12% |

| General public | 32% | 27% |

| Quakers (internal publication) | 10% | 54% |

| Government & Quakers (“all inhabitants”) | 13% | 7% |

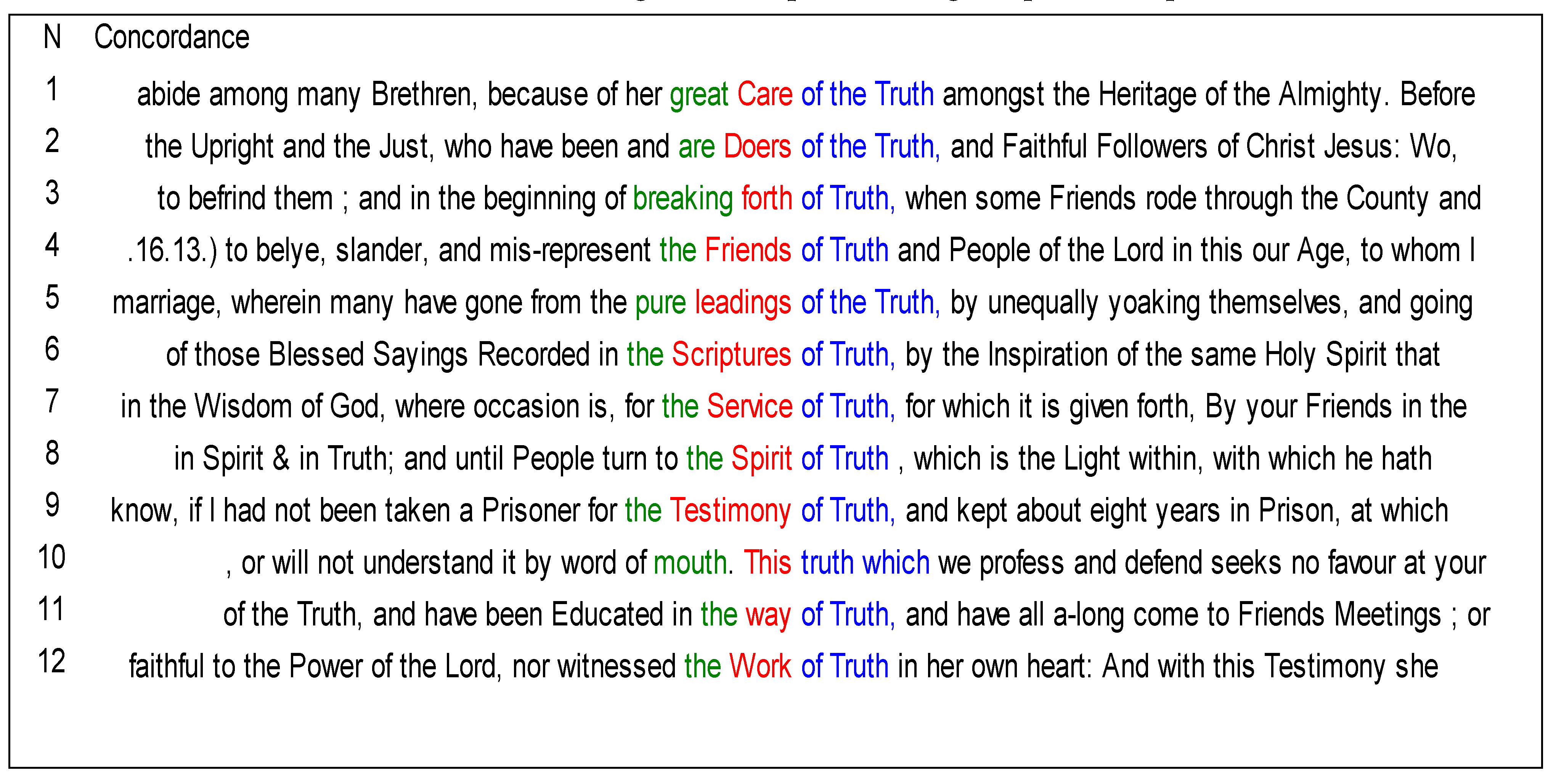

| Lexical Item | Q50s & Q60s | Q-Post73 |

|---|---|---|

| light | 356 | 186 |

| spirit(s) | 287 | 301 |

| truth | 179 | 195 |

| witness | 163 | 74 |

| conscience(s) | 118 | 63 |

| within | 68 | 36 |

| testimony | 51 | 89 |

| wait/waiting | 46 | 60 |

| of God in | 22 | 13 |

| inward | 20 | 28 |

| convince/-ment | 18 | 21 |

| day of the Lord | 12 | 10 |

| leading(s) | 6 | 7 |

| Day of the Lord | Sin being judged in the conscience by the light within in this life. The inward judgings and terrours by the light Christ within, and that in this world. |

| Leadings in Spirit | The motions of the light within, immediate inspirations and teachings |

| Testifie to the light in the Conscience | Appealing or speaking to Christ the light within. |

| Bearing Testimony to the light | Declaring for, and from the light within. |

| Witnessing to the Truth | Declaring, or suffering for the light within, and its dictates. |

| We Witness | We experience, we speak it from the testimony and feeling of the light and motions within. |

| Spirit of God | The light within every man, God the Father, Son, Holy Ghost, without distinction. (=that of God) |

| Conversion | A full obedience to the light in the Conscience: a total freedom from the prevailing of any sin. (Quakers themselves preferred the term convincement to conversion, in a rather different sense.) |

| Wait on the light | Desisting from a search after Truth by any external means, and passively attending to the motions and teachings within. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roads, J. Change and Continuity in Quaker Rhetoric after 1660. Religions 2021, 12, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030168

Roads J. Change and Continuity in Quaker Rhetoric after 1660. Religions. 2021; 12(3):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030168

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoads, Judith. 2021. "Change and Continuity in Quaker Rhetoric after 1660" Religions 12, no. 3: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030168

APA StyleRoads, J. (2021). Change and Continuity in Quaker Rhetoric after 1660. Religions, 12(3), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030168