Online Live-Stream Broadcasting of the Holy Mass during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland as an Example of the Mediatisation of Religion: Empirical Studies in the Field of Mass Media Studies and Pastoral Theology

Abstract

:1. The Mediatisation of Religion during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Introduction and Approach of the Analysis

2. The Mediatisation of Religion and the Significance of the Internet

3. The Analysis of the Problem from the Point of View of the Parishes of the Roman Catholic Church in Poland: Insights from Elements of Communication and Media Issues

- urban gminas/parishes: their boundaries coincide with the boundaries of the city or town forming the gmina (18.9% of the total);

- urban-rural gminas/parishes: they include both the city or town within its administrative boundaries and areas outside these boundaries (15.6% of the total);

- rural gminas/parishes: they do not have a city or town within their area (65.5% of the total) (Sadłoń 2013, p. 38; Zdaniewicz 2001).

4. The Practice of Transmitting the Holy Mass by Internet in Poland: The Four Stage Analysis

4.1. “See”—The Outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the First Reactions from State Authorities, the Holy See, and Bishops

4.2. “Judge”—Theological and Legal Reflection to Date on the Broadcasting of the Eucharist

- it was feared that the faithful would treat radio broadcast as sufficient to comply with the duty to attend the Eucharist on Sundays and holy days of obligation, replacing direct participation at the place of celebration with the concept of indirect participation, treated as an intentional act;

- the problem was raised of possible inadequacy of the place where the broadcast was received, but doubts were also voiced concerning the radio as a medium: it was pointed out that it was not suitable to listen to the words of the Eucharist from a device which sooner or later would provide inappropriate music or words perceived by Catholics as offensive to God and religion or even blasphemous;

- the danger of losing the liturgical essence of the Eucharist was pointed out, as it is impossible to physically receive Holy Communion (Szczepaniak 2012, p. 16).

- the very fact of broadcasting the Eucharist is a positive phenomenon, with broadcasts being of “valuable help” (John Paul II 1998, p. 54) for those who, for serious reasons, cannot physically attend the Eucharist. Draguła (2020a) refers this point to the theology of the image, formulated by the Second Council of Nicaea against iconoclasts: “He who pays homage to the image, pays homage to the Being it represents” (BF 1988, p. 637). Therefore, praying and performing gestures in front of a radio receiver or screen refers to the reality of the mystery which is performed at the same time but in a different place;

- although “disease, disability, or other serious cause” (John Paul II 1998, p. 54) exempt you from the obligation to participate in the Eucharist, they does not blur the nature of the holy day. In such situations it is necessary to attend Mass “from afar” (John Paul II 1998, p. 54). As an essential means of this participation, the document mentions the Mass readings and prayers as well as the desire for the Eucharist (John Paul II 1998, p. 54). Broadcasts give the opportunity to “unite with the Eucharist celebrated in holy places” (John Paul II 1998, p. 54), but are not necessary for this. What is more important is individual and community prayer, Mass readings and, above all, spiritual communication with the community of believers. “The Church intends to give priority to living prayer, whether individual or in community, whereby the broadcast is only supposed to help. It is not an aim in itself, but a spiritual union with the praying Church. Broadcast is only a means, a relatively necessary means” (Draguła 2020a). Therefore, it is considered unacceptable to participate in a broadcast recording released in the form of a podcast, as this solution does not meet the requirement for participation “here and now”. This is evidenced by the reaction of bishops to the fact that recordings of Mass broadcasts were posted by some parishes on their social media profiles. For example, the Bishop of Opole decreed: “Records of religious rituals must not be published after they have finished. They may only be broadcast in real time (live-streaming). All past recordings, which can be found on parish websites and in their social media, which contain religious rites, are to be removed within seven days of the promulgation of this Decree. However, photographs are allowed to remain” (Czaja and Lippa 2020);

- participation in the broadcast Eucharist by a person who has no obstacle in going to the church is not in the fulfilment of the Sunday duty (John Paul II 1998, p. 54; 1997, p. 57). Therefore “despite allowing the Holy Mass broadcast, listening to it (even actively, with giving responses, singing, assuming the adequate posture at the specific moment in liturgy) is not an ordinary way of participating in the liturgy” (Adamski 2019, p. 242).

4.3. “Act”: Online Communication Tools for Spiritual Communication between the Parish and the Faithful—Empirical Studies

4.3.1. Church Action in Response to the Pandemic Situation

- Non-media pastoral non-standard (ambient) activities. For example, parish priests helped the faithful to participate in Mass outside the church building (keeping social distance) by putting loudspeakers outside (Cylka 2020); the faithful could attend Mass in cars parked on the church car park (where a sound system had been installed); mobile confessionals were set up, Easter food was blessed from a car or motorbike moving through the village, as well as many other activities which are unusual from the pastoral point of view (Dobrołowicz 2020; Xiong et al. 2020, p. 26).

- Large-scale Mass broadcasts by the media (via the radio, television, and the Internet). Several radio and television stations (including liberal and secular ones, and not only those considered strictly religious or pro-Catholic) changed their schedules to include Sunday Eucharist broadcasts. Market research has shown that this step generated a significant increase in their audience (even a ten-fold increase in the case of the niche TV channel Polsat Rodzina, Kurdupski 2020). Interestingly, such actions were also carried out by cable operators, who decided to broadcast Masses from local parishes. Thanks to this, the maintenance of bonds and community in difficult times was ensured not only in a general dimension, but also at a sub-local level, focused on the individual and local churches (NB 2020).

- Grassroots initiatives of parishes to independently broadcast the Mass over the Internet. The stimulus for such activity was, among other things, provided by incentives from diocesan bishops. Therefore, naturally, questions about the scale of this phenomenon and reasons for parishes to undertake (or not to undertake) the discussed activities appeared. It is also noteworthy that the rapid and rather uncontrolled increase in the number of online broadcasts from parish churches departed from the practice sanctioned by Church documents to date. Before the outbreak of the pandemic, the benefit of broadcasting Masses was appreciated by the Catholic Church, which held a favourable attitude towards the broadcasts. Still, it was rather cautious from the points of view of theology and canon law. It is worth mentioning that it is this trend that is the subject of the empirical research presented here.

4.3.2. Sample of Reference and Procedure

- Nmin—minimum sample size;

- NP—size of the population from which the sample was taken;

- α—confidence level for the results, the value of result Z in the normal distribution for the assumed level of materiality, e.g., 1.96;

- f—fractional size;

- e—assumed maximum error, expressed in a fractional number, e.g., 3% is 0.03.

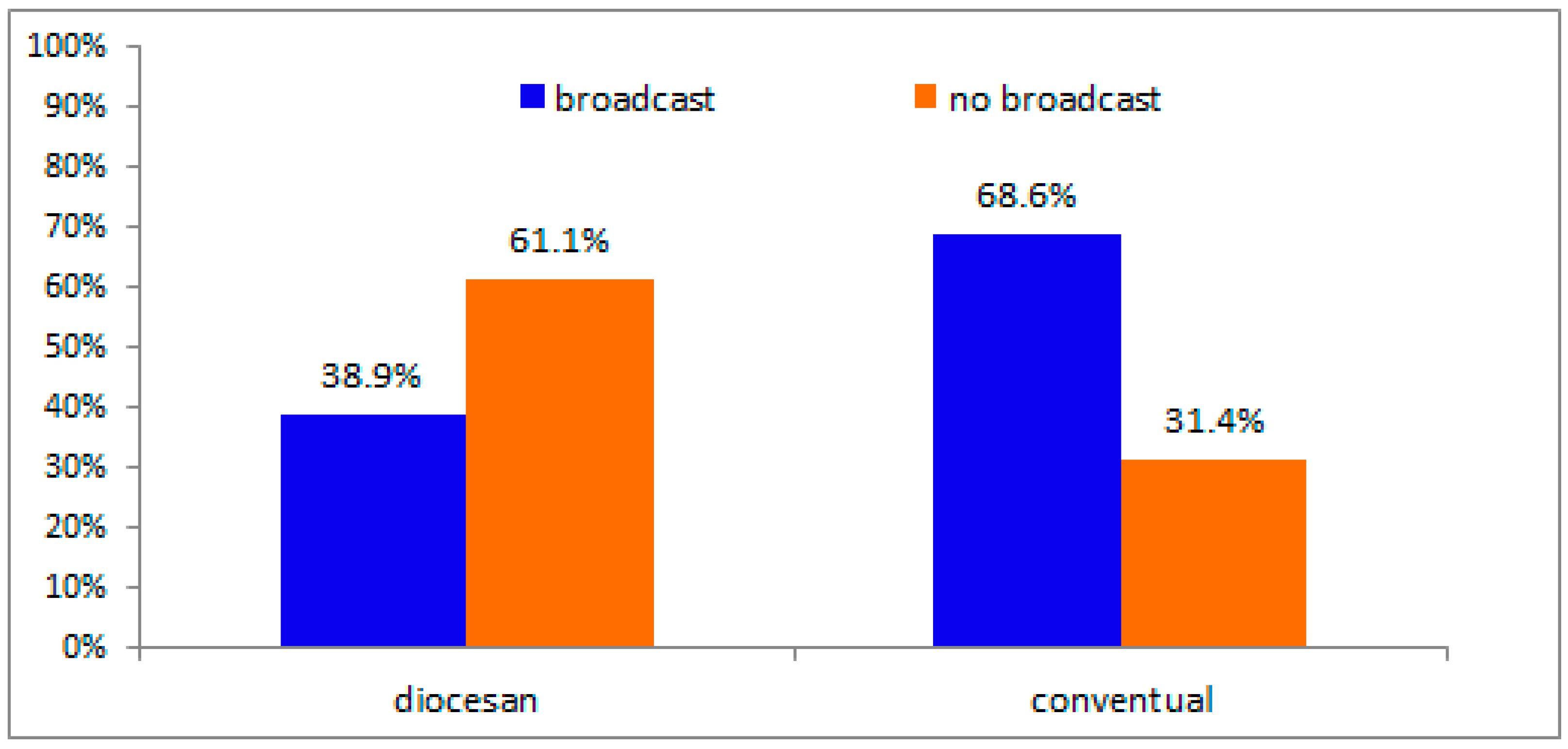

- Conventual and diocesan parishes;

- Rural, urban-rural, and urban parishes.

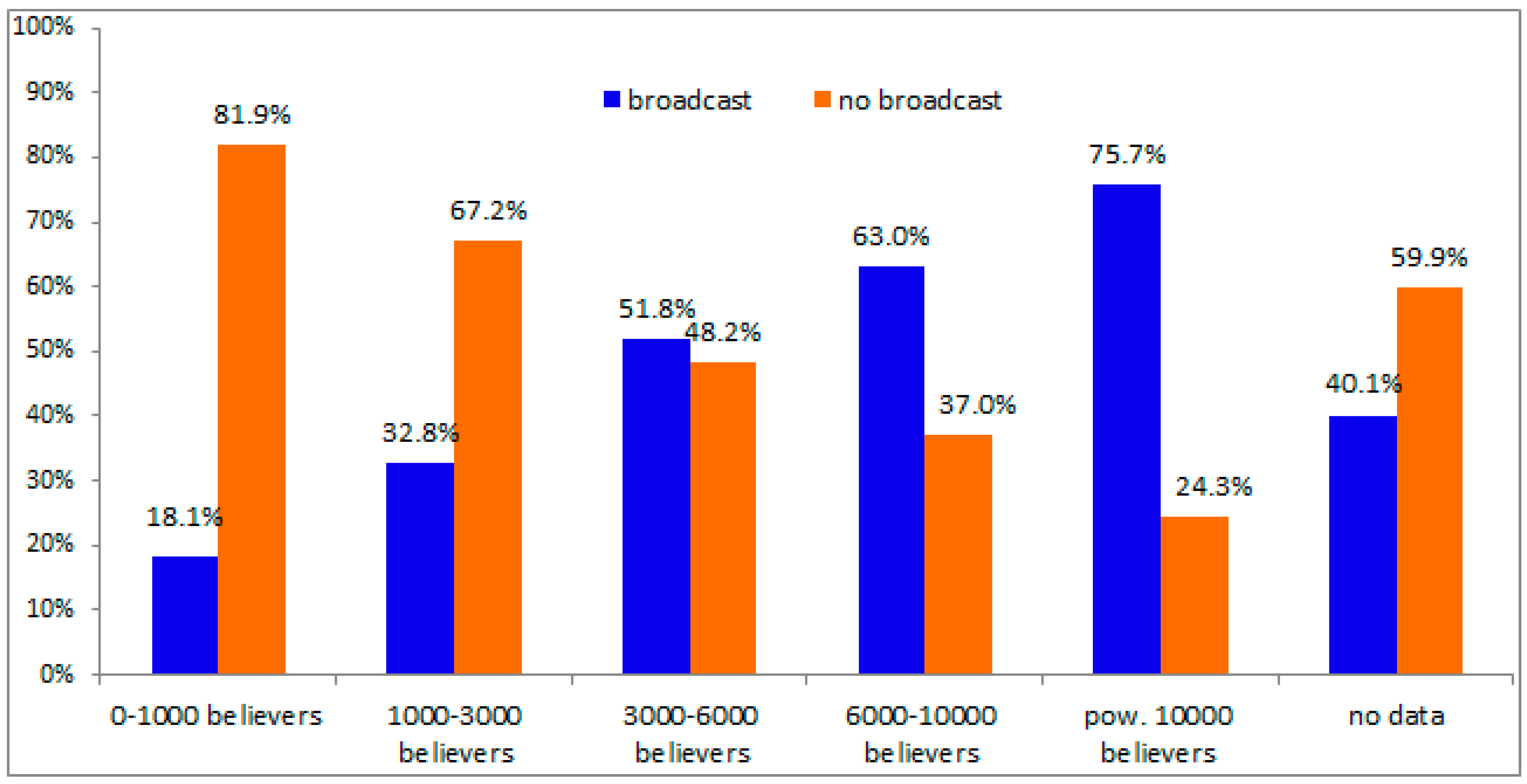

- From 0 to 1000 believers—the group of parishes with the smallest population, consisting mostly of rural parishes and sometimes small urban parishes. The staff is usually limited to one parish priest. The percentage share in the sample is 15.3%4;

- 1001–3000—the largest group of parishes. Depending on the diocese, the number of 2500–3000 believers is the threshold for assigning more priests to the parish to help the parish priest. The percentage of the sample is 47.8%;

- 3001–6000—a group of relatively large parishes, including rural, urban-rural, and typically urban parishes. There are usually 1–2 vicars assigned to help parish priests in such parishes. The percentage of the sample is 18.3%;

- 6001–10,000—a group of large parishes, usually urban or urban-rural, where the parish priest is assisted by 3–4 vicars. The percentage of the sample is 8.7%;

- Above 10,000—the largest parishes, usually in medium and large cities, with numerous pastoral staff. The percentage of the sample is 9.9%.

- which diocese a parish belongs to (the number of parishes from a given diocese was determined according to the total number of parishes in that diocese in proportion to the population);

- type of parish: diocesan or conventual;

- type of parish: rural, urban-rural, or urban;

- size of the parish;

- territorial assignment to one of the nine areas of Poland (north-east, north-centre, north-west, east-centre, centre, west-centre, south-east, south-centre, south-west5);

- classification of dioceses according to two indicators: dominicantes (percentage of believers attending Sunday Mass in relation to all believers) and communicantes (percentage of Catholics receiving Holy Communion during Sunday Eucharist in relation to the total number of believers) (data from the Institute of Statistics of the Catholic Church of 21 October 2018 (Institute for Catholic Church Statistics 2020) as well as data on the number of priests per 100,000 Catholics (data for 2017 [Institute for Catholic Church Statistics 2018]));

- the role of diocesan bishops in encouraging priests to broadcast Sunday Mass (data from analyses of documents—bishops’ decrees, pastoral letters, and others—published on diocesan websites);

- at least one Sunday Mass broadcast by the parish;

- broadcast channel (Facebook, YouTube, other technical solutions, e.g., websites, service providers etc.);

- broadcasting on their profiles or using profiles of other persons/institutions (if social media were used);

- sharing the broadcast signal with other channels (e.g., a website).

4.3.3. Polish Parishes and Mass Broadcasts—Research Results

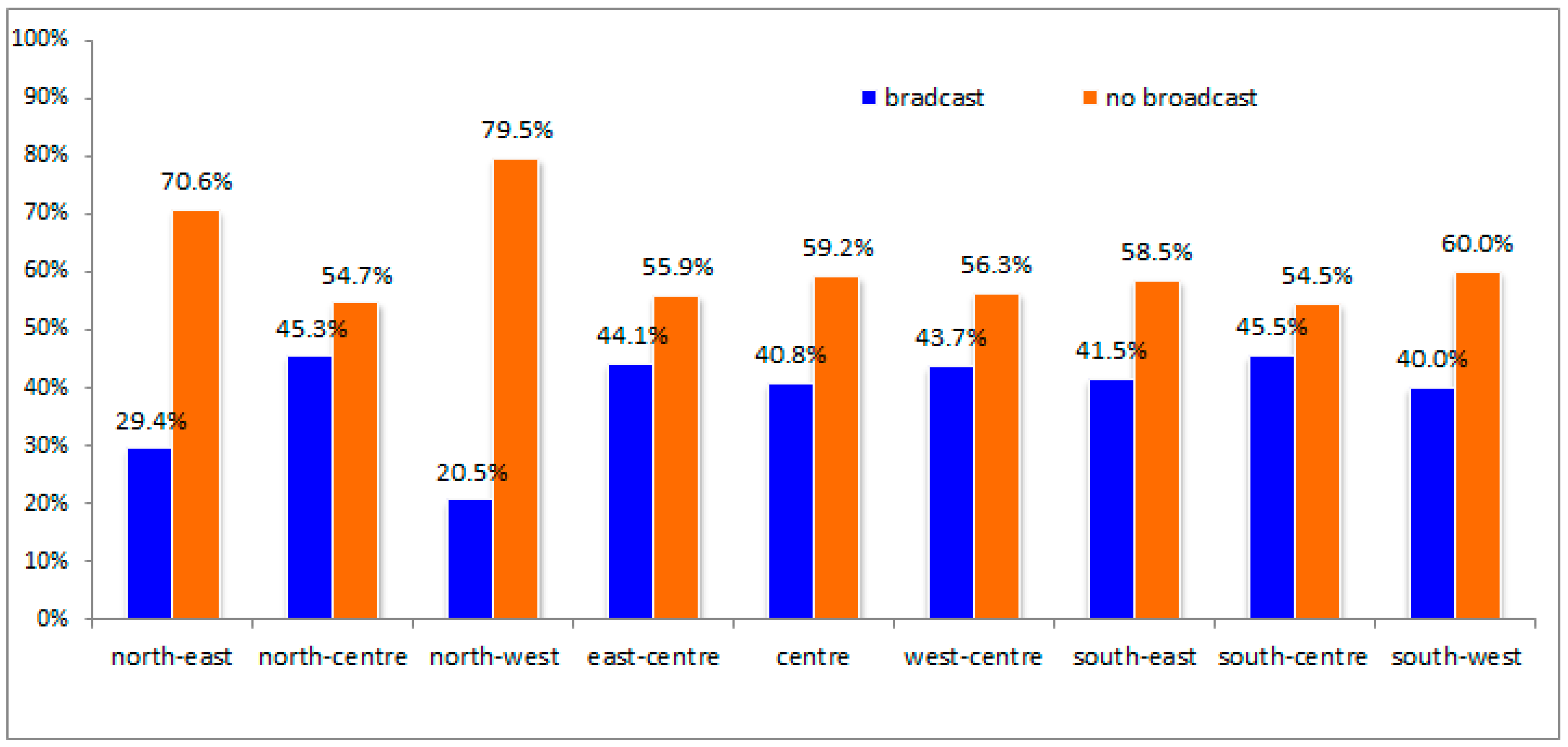

4.3.4. The Frequency of Broadcast and the Geographical Location of Parishes (the Region of Poland)

4.3.5. The Frequency of Transmission versus Parish Size and Type

4.3.6. The Frequency of Broadcasting versus the Dominicantes/Communicantes Indicators, the Proportion of Priests to Catholics in a Given Diocese, and the Participantes Indicator

5. Final Comments and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ad/Stacja7. 2020. Google znosi wymóg 1000 subskrypcji kanałów transmitujących Msze. Available online: https://stacja7.pl/z-kraju/google-znosi-wymog-1000-subskrypcji-kanalow-transmitujacych-msze (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Adamski, Andrzej. 2012. Media w Analogowym i Cyfrowym Świecie. Warszawa: Elipsa. [Google Scholar]

- Adamski, Andrzej. 2015. Media as the intersphere of human life. Another view on the mediatization of communication theory. In Megatrends and Media. Media Farm—Totems and Taboo. Edited by Dana Petranová and Slavomír Magál. Trnava: Faculty of Mass Media Communication University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava, pp. 16–39. [Google Scholar]

- Adamski, Andrzej. 2019. Sacrum in the Digital World: The Processes of Remediation on the Example of the Liturgical Books of the Catholic Church. In Remediation: Crossing Discursive Boundaries. Central European Perspective. Edited by Bogumiła Suwara and Mariusz Pisarski. Berlin-Bratysława: Peter Lang/Veda Publishing House, pp. 227–48. [Google Scholar]

- Adamski, Andrzej, and Grzegorz Łęcicki. 2016. Theology and media studies: Interdisciplinarity as a platform for joint reflection on the media. Studia Medioznawcze 1: 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroziak, Łukasz, Adam Czerwiński, Katarzyna Dębkowska, Jacek Grzeszak, Urszula Kłosiewicz-Górecka, Jan Strzelecki, Anna Szymańska, Ignacy Święcicki, Piotr Ważniewski, and Katarzyna Zybertowicz. 2020. Internet—Strategiczna infrastruktura w czasach pandemii. Tygodnik Gospodarczy PIE 12: 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ampuja, Marko, Juha Koivisto, and Esa Väliverronen. 2014. Strong and Weak Forms of Mediatization Theory. A Critical Review. Nordicom Review 36: 111–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andok, Mónika, and Fanni Vígh. 2018. Religious communities’ digital media use: A Hungarian case study. In Believe in Technology: Mediatization of the Future and the Future of Mediatization. Edited by Mihaela-Alexandra Tudor and Stefan Bratosin. Les Arcs: IARSIC France, pp. 378–92. [Google Scholar]

- Archidiecezja Krakowska. 2020. Jak Dobrze Przeżyć Mszę św. za Pośrednictwem Mediów? March 13. Available online: https://diecezja.pl/aktualnosci/jak-dobrze-przezyc-msze-sw-za-posrednictwem-mediow/ (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Asp, Kent. 1990. Medialization, media logic and mediarchy. Nordicom Review 11: 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bekkering, Denis J. 2018. American Televangelism and Participatory Cultures. Fans, Brands, and Play with Religious “Fakes”. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict XVI. 2006. Homily during a Pastoral Visit to Our Lady Star of Evangelization Parish of Rome. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2006/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20061210_star-evangelization.html (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Benedict XVI. 2007. Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation “Sacramentum Caritatis” of the Holy Father Benedict Xvi to the Bishops, Clergy, Consecrated Persons and the Lay Faithful on the Eucharist as the Source and Summit of the Church’s Life and Mission. Available online: http://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_ben-xvi_exh_20070222_sacramentum-caritatis.html (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Berger, Teresa. 2013. @Worship. Exploring Liturgical Practices in Cyberspace. Questions Liturgiques/Studies in Liturgy 94: 266–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BF. 1988. Breviarium Fidei. Wybór Doktrynalnych Wypowiedzi Kościoła. Edited by Stanisław Głowa and Ignacy Bieda. Poznań: Księgarnia Św. Wojciecha. [Google Scholar]

- Biuro Prasowe KEP. 2020a. Google ułatwia Parafiom Transmisje na YouTube. Available online: https://episkopat.pl/google-ulatwia-parafiom-transmisje-na-youtube (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Biuro Prasowe KEP. 2020b. Rzecznik Episkopatu o Przeżywaniu TRANSMISJI Mszy Świętych. Available online: https://episkopat.pl/rzecznik-episkopatu-o-przezywaniu-transmisji-mszy-swietych/ (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Bratosin, Stefan. 2016. La médialisation du religieux dans la théorie du post néo-protestantisme. Social Compass 63: 405–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratosin, Stefan. 2020. Mediatization of Beliefs: The Adventism from “Morning Star” to the Public Sphere. Religions 11: 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretthauer, Berit. 1995. The challenge of televangelism. Peace Review 7: 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britannica. 2013. Young Christian Workers. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/event/Young-Christian-Workers (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Butkiewicz, Magdalena, and Grzegorz Łęcicki. 2018. Ewolucja i specyfika teologii mediów w systemie nauk teologicznych i nauk o mediach. In Teologia Środków Społecznego Przekazu w Naukach o Mediach. Edited by Jerzy Olędzki. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo UKSW, pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2004. Challenges created by online religious networks. Journal of Media and Religion 3: 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2005. Making Space for Religion in Internet Studies. The Information Society 21: 309–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2010. When Religion Meets New Media. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi A., ed. 2013. Digital Religion. Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi A., and Michael W. DeLashmutt. 2014. Studying Technology and Ecclesiology in Online Multi-Site Worship. Journal of Contemporary Religion 29: 267–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBOS. 2016. Korzystanie z Religijnych Stron i Portali Internetowych. 93 vols. Komunikat z badań. Warszawa: CBOS, Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2016/K_093_16.PDF (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Chmielewski, Mirosław. 2019. Edukacja medialna—Rola w Kościele i kierunki rozwoju (Media literacy—The role in the Church and the trends of development). Biuletyn Edukacji Medialnej 1: 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, Mirosław. 2020. Media Education and the New Evangelization Part One: Media Components and Challenges. Verbum Vitae 37: 407–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code of Canon Law. 1983. Vaticano: Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

- Concordat. 1998. Concordat between the Holy See and the Republic of Poland, signed in Warsaw on 28 July 1993. Dziennik Ustaw. 1998/51, poz. 318. Available online: https://pracownik.kul.pl/files/26914/public/CONCORDAT.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Congregation for the Clergy. 2020. Instruction “The Pastoral Conversion of the Parish Community in the Service of the Evangelising Mission of the Church”. Available online: https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2020/07/20/200720a.html (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Couldry, Nick. 2008. Mediatization or mediation? Alternative understandings of the emergent space of digital storytelling. New Media & Society 10: 373–91. [Google Scholar]

- Couldry, Nick, and Andreas Hepp. 2013. Conceptualising Mediatization: Contexts, Traditions, Arguments. Communication Theory 23: 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cylka, Tomasz. 2020. Koronawirus. Dominikanie zamykają kościół. W pozostałych—50 osób w środku i włączone głośniki na zewnątrz. Tak będą wyglądać niedzielne msze. Gazeta Wyborcza. March 14. Available online: https://poznan.wyborcza.pl/poznan/7,36001,25789540,koronawirus-50-osob-w-kosciele-i-wlaczone-glosniki-na-zewnatrz.html (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Cymanow-Sosin, Klaudia. 2020. Wyznaczniki dziennikarstwa preewangelizacyjnego—Kompozycja standardów w oparciu o model 4P. Kultura-Media-Teologia 41: 175–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, Andrzej, and Wojciech Lippa. 2020. Decree of the Bishop of Opole of 20 April 2020 (No. 16/2020/A/KNC-K). Available online: https://diecezja.opole.pl/index.php/homepage/aktualnosci/2554-nowy-dekret-biskupa-opolskiego (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Dębkowska, Katarzyna, Urszula Kłosiewicz-Górecka, Filip Leśniewicz, Anna Szymańska, Ignacy Święcicki, Piotr Ważniewski, and Katarzyna Zybertowicz. 2020. Nowoczesne Technologie w Przedsiębiorstwach Przed, w Trakcie i po Pandemii COVID-19; Warszawa: Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny. Available online: https://pie.net.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PIE-Raport_Nowoczesne_technologie.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Denson, Shane. 2011. Faith in Technology: Televangelism and the Mediation of Immediate Experience. Phenomenology & Practice 5: 93–119. [Google Scholar]

- Deuze, Mark. 2011. Media Life. Media, Culture & Society 33: 137–48. [Google Scholar]

- Diekema, David A. 1991. Televangelism and the mediated charismatic relationship. The Social Science Journal 28: 143–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrołowicz, Michał. 2020. Sposób Kościoła na pandemię. Spowiedź odbywa się na parking. April 10. Available online: https://www.rmf24.pl/raporty/raport-swieta/najnowsze-fakty/news-sposob-kosciola-na-pandemie-spowiedz-odbywa-sie-na-parkingu,nId,4432388 (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Drąg, Katarzyna. 2020. Revaluation of the Proxemics Code in Mediatized Communication. Social Communication 6: 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draguła, Andrzej. 2009. Eucharystia Zmediatyzowana. Teologiczno-Pastoralna Interpretacja Transmisji Mszy Świętej w Radiu i Telewizji. Zielona Góra: Wydawnictwo Vers. [Google Scholar]

- Draguła, Andrzej. 2020a. Modlitwa, nie “oglądanie”. Instrukcja obsługi transmisji Mszy świętej. Więź. March 14. Available online: http://wiez.com.pl/2020/03/14/chodzi-o-modlitwe-a-nie-ogladanie-instrukcja-obslugi-transmisji-mszy-swietej (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Draguła, Andrzej. 2020b. Powrót na Mszę, czyli kłopoty z dyspensą. Więź. June 3. Available online: http://wiez.com.pl/2020/06/03/powrot-na-msze-czyli-klopoty-z-dyspensa/#_ftn1 (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Drozdowski, Rafał, Maciej Frąckowiak, Marek Krajewski, Małgorzata Kubacka, Ariel Modrzyk, Łukasz Rogowski, Przemysław Rura, and Agnieszka Stamm. 2020. Życie Codzienne w Czasach Pandemii. Raport z Pierwszego Etapu Badań. Poznań: University of Adam Mickiewicz. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2020. Commission and European Regulators Calls on Streaming Services, Operators and Users to Prevent Network Congestion. March 19. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/commission-and-european-regulators-calls-streaming-services-operators-and-users-prevent-network (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Fossati, Luca. 2020. Messe “in onda”, ecco Come Fare. Available online: https://www.chiesadimilano.it/news/chiesa-diocesi/messe-in-onda-ecco-come-fare-339198.html (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Francis. 2013. Apostolic Exhortation “Evangelii Gaudium”. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/content/dam/francesco/pdf/apost_exhortations/documents/papa-francesco_esortazione-ap_20131124_evangelii-gaudium_en.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Francis. 2020. Santa Marta. Papa Attenti a Fede “Virtuale”. La Chiesa è con Popolo e con Sacramenti. Available online: https://www.vaticannews.va/it/papa-francesco/messa-santa-marta/2020-04/papa-francesco-messa-santa-marta-coronavirus8.html (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Gawroński, Sławomir, and Ilona Majkowska. 2018. Marketing Communication of the Catholic Church—A Sign of the Times or Profanation of the Sacred? Studia Humana 7: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giorgi, Alberta. 2019. Mediatized Catholicism—Minority Voices and Religious Authority in the Digital Sphere. Religions 10: 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goban-Klas, Tomasz. 2020. Rwący nurt Mediów. Mediocen—Nowa Faza Mediatyzacji życia Społecznego. Rzeszów-Sosnowiec: Universitas & Wydawnictwo WSIiZ. [Google Scholar]

- Golan, Oren, and Michele Martini. 2019. Religious live-streaming: Constructing the authentic in real time. Information, Communication & Society 22: 437–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, Pedro Gilberto. 2016. Mediatization: A concept, multiple voices. ESSACHESS-Journal for Communication Studies 9: 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Graca, Martin. 2020. Rate of use of social network in Catholic media in Slovakia. European Journal of Science and Theology 16: 113–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gralczyk, Aleksandra. 2020. Social media as an effective pastoral tool. Forum Teologiczne 21: 237–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanas, Zenon. 2013. Internet religijny a religijność internetowa: Eksploracja pola badawczego. In Media w Transformacji. Edited by Aleksandra Gralczyk, Krzysztof Marcyński SAC and Monika Przybysz. Warszawa: Dom Wydawniczy Elipsa, pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Helland, Christopher. 2000. Online Religion/Religion Online and Virtual Communities. In Religion on the Internet: Research Prospects and Promises. Edited by Jeffrey K. Hadden and Douglas E. Cowan. Amsterdam, London and New York: JAIPress/Elsevier Science, pp. 205–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2008a. The mediatization of religion. A theory of the media as agents of religious change. Nordic Journal of Media Studies 6: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2008b. The Mediatization of Society. A Theory of the Media as Agents of Social and Cultural Change. Nordicom Review 29: 105–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2011. The mediatisation of religion: Theorising religion, media and social change. Culture and Religion: An Interdisciplinary Journal 12: 119–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, Iwona. 2018. Teologia środków społecznego przekazu a paradygmat nauki o mediach. In Teologia Środków Społecznego Przekazu w Naukach o Mediach. Edited by Jerzy Olędzki. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo UKSW, pp. 195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, Stewart M. 1991. Televangelism Reconsidered. Media Information Australia 60: 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, Stewart. 2011. Media and the imagination of religion in contemporary global culture. European Journal of Cultural Studies 14: 610–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, Tim. 2011. Contemporary Religious Community and the Online Church. Information, Communication & Society 14: 1118–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idziemy.pl/rm. 2020. Edukacja medialna—Nowy przedmiot w polskich seminariach duchownych. Idziemy.pl. March 9. Available online: http://idziemy.pl/kosciol/edukacja-medialna-nowy-przedmiot-w-polskich-seminariach-duchownych/63373 (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Ignatowski, Grzegorz, Łukasz Sułkowski, and Robert Seliga. 2020. Brand Management of Catholic Church in Poland. Religions 11: 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Catholic Church Statistics. 2018. Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae in Polonia AD 2018. Warsaw: Institute for Catholic Church Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Catholic Church Statistics. 2020. Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae in Polonia AD 2020. Warsaw: Institute for Catholic Church Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- International Theological Commission. 2011. Theology Today: Perspectives, Principles and Criteria. Vatican. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/cti_documents/rc_cti_doc_20111129_teologia-oggi_en.html (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Jacobs, Stephen. 2007. Virtually Sacred: The Performance of Asynchronous Cyber-Rituals in Online Spaces. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12: 1103–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeżak-Śmigielska, Magdalena, Monika Lender-Gołębiowska, and Maciej Makuła. 2018. Teologia mediów i komunikacji jako nowa perspektywa badawcza w naukach o mediach. In Teologia Środków Społecznego Przekazu w Naukach o Mediach. Edited by Jerzy Olędzki. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo UKSW, pp. 171–94. [Google Scholar]

- John Paul II. 1996. Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation “Vita Consecrata”. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_jp-ii_exh_25031996_vita-consecrata.html (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- John Paul II. 1997. Apostolic Exhortation “Catechesi Tradendae”. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_jp-ii_exh_16101979_catechesi-tradendae.html (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- John Paul II. 1998. Apostolic Letter “Dies Domini” to the Bishops, Clergy and Faithful of the Catholic Church on Keeping the Lord’s Day Holy. Available online: http://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_letters/1998/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_05071998_dies-domini.html (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- John XXIII. 1961. Encyclical Letter on Christianity and Social Progress Mater Et Magistra. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/content/john-xxiii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_j-xxiii_enc_15051961_mater.html (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Jupowicz-Ginalska, Anna, Marcin Szewczyk, Andrzej Kiciński, Barbara Przywara, and Andrzej Adamski. 2021. Dispensation and Liturgy Mediated as an Answer to COVID-19 Restrictions: Empirical Study Based on Polish Online Press Narration. Religions 12: 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasowski, Roland. 2018. Edukacja Medialna w Wyższych Seminariach Duchownych w Polsce po roku 1992—Streszczenie Rozprawy Doktorskiej; Electronic Document. Warsaw: Theological Faculty of UKSW. Available online: https://teologia.uksw.edu.pl/sites/default/files/streszczenie%20pracy-%20ks.%20Ronald%20Kasowski.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Konferencja Episkopatu Polski. 2017. Dyrektorium w sprawie Mszy św. transmitowanej przez telewizję. Akta Konferencji Episkopatu Polski 29: 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kiciński, Andrzej. 2011. Katecheza osób z Niepełnosprawnością Intelektualną w Polsce po Soborze Watykańskim II. Lublin: KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejska, Marta. 2018. Online Catholic Communities. Community, Authority, and Religious Individualisation. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Korpi, Michael F., and Kyong Liong Kim. 1986. The Uses and Effects of Televangelism: A Factorial Model of Support and Contribution. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 25: 410–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Królak, Tomasz. 2020. Kościół w czasie pandemii—Nowa era Internetu? Ekai.pl. June 12. Available online: https://ekai.pl/kosciol-w-pandemii-nowa-era-internetu (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Krotz, Friedrich. 2007. Mediatisierung. Fallstud. zum Wan. von Komm. Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Krotz, Friedrich. 2009. Mediatization: A concept with which to grasp media and societal change. In Mediatization: Concept, Changes, Consequences. Edited by Knut Lundby. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdupski, Michał. 2020. Rekordy oglądalności mszy świętych w telewizji. Wirtualnemedia.pl. April 15. Available online: https://www.wirtualnemedia.pl/artykul/duzy-wzrost-ogladalnosci-mszy-swietych-koronawirus-analiza (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Leśniczak, Rafał. 2018. Teologia środków społecznego przekazu i nauki o mediach jako dwie perspektywy badań wizerunku medialnego przywódców religijnych Kościoła katolickiego—Kilka uwag do dyskusji. In Teologia Środków Społecznego Przekazu w Naukach o Mediach. Edited by Jerzy Olędzki. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo UKSW, pp. 339–56. [Google Scholar]

- Leśniczak, Rafał. 2019. Mediatization of Institutional Communication of the Catholic Church. Reflections on the Margins of the Migration Crisis. Studia Medioznawcze 3: 237–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leśniczak, Rafał. 2020. Komunikowanie polskich biskupów w kontekście kryzysu pedofilii. W trosce o zasady skutecznej komunikacji. Kultura-Media-Teologia 42: 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljequist, Fredrik. 2016. Live-Streaming as a Marketing Channel in the Swedish Music Industry. Stockholm: KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:942217/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Lundby, Knut. 2009. Mediatization: Concept, Changes, Consequences. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Lundby, Knut. 2011. Patterns of Belonging in Online/Offline Interfaces of Religion. Information, Communication & Society 14: 1219–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundby, Knut. 2014. Mediatization of Communication. 21 vols. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. [Google Scholar]

- Magnin, Thierry. 2013. Scientists and Theologians in Front of the Mystery. In Transdisciplinary Theory & Practice. Edited by Basarab Nicolescu and Atila Ertas. Lubbock: The Atlas, pp. 29–58. [Google Scholar]

- Makuła, Maciej. 2019. Transmisje Mszy świętych w live-streamingu w Internecie. analiza możliwości, postulaty i propozycje. Seminare 1: 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, Luis Mauro Sá. 2020. Mediatization of Religion: Three Dimensions from a Latin American/Brazilian Perspective. Religions 11: 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mette, Norbert. 2005. Einführung in die Katholische Praktische Theologie. Darmstadt: Wbg Academic in Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft (WBG). [Google Scholar]

- Midali, Mario. 2011. Teologia Pratica. 5. Per un’attuale Configurazione Scientifica. Roma: Las. [Google Scholar]

- Mikuláš, Peter, and Oľga Chalányová. 2017. Celebritization of religious leaders in contemporary culture. European Journal of Science and Theology 13: 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mishol-Shauli, Nakhi, and Oran Golan. 2019. Mediatizing the Holy Community—Ultra-Orthodoxy Negotiation and Presentation on Public Social-Media. Religions 10: 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Misztal, Wojciech. 2020. Powszechne oddziaływanie: Przekaz medialny i pierwsze papieskie orędzie radiowe. Kultura-Media-Teologia 42: 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NB. 2020. Telewizje kablowe oferują transmisje mszy świętych z lokalnych parafii. Wirtualnemedia.pl. March 25. Available online: https://www.wirtualnemedia.pl/artykul/msza-swieta-w-telewizji-gdzie-ogladac-i-sluchac-lista-miast (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Nguyen, Minh Hao, Jonathan Gruber, Jaelle Fuchs, Will Marler, Amanda Hunsaker, and Eszter Hargittai. 2020. Changes in Digital Communication during the COVID-19 Global Pandemic: Implications for Digital Inequality and Future Research. Social Media + Society 6: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, Helen. 2020. The Absence of Presence and the Presence of Absence: Social Distancing, Sacraments, and the Virtual Religious Community during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Religions 11: 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastwa, Rafał. 2020. Komunikowanie religijne na przykładzie Kościoła katolickiego w Polsce z uwzględnieniem kontekstu pandemii koronawirusa. Kultura-Media-Teologia 41: 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, Karine, and Gwendal Simon. 2015. YouTube Live and Twitch: A Tour of User-Generated Live-streaming Systems. Paper presented at ACM Press the 6th ACM Multimedia Systems Conference, Portland, OR, USA, March 18–20; pp. 225–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarek, Walery. 2008. Wstęp do Nauki o Komunikowaniu. Warszawa: PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Pope Paul VI. 1965. Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World Gaudium et spes; Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, Second Vatican Council. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_cons_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Radej, Maciej. 2020. “Mira sane ope Marconiana”. Pierwsze radiowe transmisje mszy świętych. Kultura-Media-Teologia 43: 88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Reimann, Ralf Peter. 2017. “Uncharted Territories”: The Challenges of Digitalization and Social Media for Church and Society. The Ecumenical Review 69: 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robak, Marek. 2018. Badania stron internetowych diecezji w Polsce metodą WebScan. In Teologia Środków Społecznego Przekazu w Naukach o Mediach. Edited by Jerzy Olędzki. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo UKSW, pp. 359–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ruether, Traci. 2019. Live-streaming vs. Traditional Live Broadcasting: What’s the Difference. Available online: https://www.wowza.com/blog/streaming-vs-cable-satellite-broadcasting (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Sadłoń, Wojciech. 2013. Społeczny wymiar parafii wiejskiej w Polsce na podstawie badań statystycznych. Trzeci Sektor 29: 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sadłoń, Wojciech. 2018. Religijność w strukturze polskiego społeczeństwa. Wstęp do zagadnienia. Warszawskie Studia Pastoralne 13: 183–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sands, Justin. 2018. Introducing Cardinal Cardijn’s See-Judge-Act as an Interdisciplinary Method to Move Theory into Practice. Religions 9: 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serwis RP. 2020. Wprowadzamy nowe zasady bezpieczeństwa w związku z koronawirusem. March 24. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/koronawirus/wprowadzamy-nowe-zasady-bezpieczenstwa-w-zwiazku-z-koronawirusem (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Seweryniak, Henryk. 2010. Teologie na “progu domu”. Kultura-Media-Teologia 1: 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, Phil, and Graham Walter, eds. 1999. Telepresence. Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Sierocki, Radosław. 2018. Praktykowanie Religii w Nowych Mediach. Katolicka Przestrzeń Facebooka. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek. [Google Scholar]

- Skačan, Juraj. 2017. On virtual reality of religion. European Journal of Science and Theology 13: 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Soukup, Paul. 2019. Some past meetings of communication, theology, and media theology. Kultura-Media-Teologia 38: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacja7/redakcja. 2020. Msza święta w domu. Jak najlepiej ją przeżyć? Stacja7.pl. March 21. Available online: https://stacja7.pl/styl-zycia/msza-swieta-w-domu-jak-najlepiej-ja-przezyc/ (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Statistics Poland. 2020a. Administrative Division of Poland. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/regional-statistics/classification-of-territorial-units/administrative-division-of-poland/ (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Statistics Poland. 2020b. Types of Gminas and Urban and Rural Areas. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/regional-statistics/classification-of-territorial-units/administrative-division-of-poland/types-of-gminas-and-urban-and-rural-areas/ (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Sułkowski, Łukasz. 2020. Covid-19 Pandemic; Recession, Virtual Revolution Leading to De-globalization? Journal of Intercultural Management 1: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkowski, Lukasz, and Grzegorz Ignatowski. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Organization of Religious Behaviour in Different Christian Denominations in Poland. Religions 11: 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Święciński, Bartosz. 2020. Rzecznik KEP: Obecność Kościoła w mediach społecznościowych jest niezbędna. Radio Warszawa. September 6. Available online: https://radiowarszawa.com.pl/rzecznik-kep-obecnosc-kosciola-w-mediach-spolecznosciowych-jest-niezbedna/ (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Szczepaniak, Maciej. 2012. Radiowa transmisja mszy św. z Kongresu Eucharystycznego w Dublinie. Przełom w recepcji transmisji radiowych w praktyce eklezjalnej. Kultura-Media-Teologia 9: 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, Maciej. 2018. Wideosłowa—o przepowiadaniu w formie audiowizualnej. Polonia Sacra 22: 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szocik, Konrad, and Joanna Wisła-Płonka. 2018. Moral Neutrality of Religion in the Light of Conflicts and Violence in Mediatized World. Social Communication 4: 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Church of England. 2020. COVID-19 Livestreaming Worship. Available online: https://www.churchofengland.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/COVID%2019%20Livestreaming%20Worship%20v1.0_1.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- The Conference of Major Superiors of Women Religious Orders. 2019. Ewangelizacja przez media. Zestawienie statystyczne zaangażowania sióstr w duszpasterstwo stan na 01.01.2019 r. Available online: https://zakony-zenskie.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Duszpasterstwo_2019.01.01-.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- The Council of Ministers of the Republic of Poland. 2020. Narodowy Plan Szerokopasmowy. Załącznik do uchwały nr 27/2020 Rady Ministrów z dnia 10 marca 2020. Available online: https://mc.bip.gov.pl/fobjects/download/776267/aktualizacja-narodowego-planu-szerokopasmowego-przyjeta-przez-rade-ministrow-w-dniu-10-marca-2020-r-pdf.html (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Tudor, Mihaela Alexandraand, and Stefan Bratosin. 2018. Croire en la Technologie: Médiatisation du Futur et Futur de la Médiatisation. Iarsic: Les Arcs. [Google Scholar]

- Tudor, Mihaela Alexandraand, and Stefan Bratosin. 2020. French Media Representations towards Sustainability: Education and Information through Mythical-Religious References. Sustainability 12: 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tworzydło, Dariusz, Sławomir Gawroński, and Marek Zajic. 2020. Catholic Church in Poland in the Face of Paedophilia. Analysis of Image Actions. European Journal of Science and Theology 16: 157–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, Bartosz. 2012. Wokół religii mediów. Kultura-Media-Teologia 11: 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgosz, Zbigniew. 2020. Jak zamienić dom w domowy Kościół? Jak przeżyć w nim Mszę św.? Jak przygotować mały ołtarzyk? Wiara.pl. March 13. Available online: https://kosciol.wiara.pl/doc/6215631.Jak-zamienic-dom-w-domowy-Kosciol-Jak-przezyc-w-nim-Msze-sw-Jak (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Xiong, Jianhui (Jane), Nazila Isgandarova, and Amy Elizabeth Panton. 2020. annuarCOVID-19 Demands Theological Reflection: Buddhist, Muslim, and Christian Perspectives on the Present Pandemic. International Journal of Practical Theology 24: 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, William. 2019. Reverend Robot: Automation and Clergy. Zygon® 54: 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young Christian Workers. 2020. The Method of See, Judge, Act, Review. Available online: https://ycw.ie/resources/see-judge-act-resources-2 (accessed on 22 November 2020).

- Zdaniewicz, Witold. 2001. Dane Statystyczne Dotyczące Diecezji. Available online: https://opoka.org.pl/biblioteka/V/trans/msze/stat2.html (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Zimmermann, Carol. 2020. Parishes step up their social media efforts by posting online Masses. Crux. March 26. Available online: https://cruxnow.com/church-in-the-usa/2020/03/parishes-step-up-their-social-media-efforts-by-posting-online-masses/ (accessed on 25 November 2020).

| 1 | In an earlier text, we examined the Polish media’s discourse on the phenomenon of broadcasting the Eucharist during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland (Jupowicz-Ginalska et al. 2021). Subsequent articles we are preparing will include, among others, an analysis of the Polish bishops’ approach to the broadcasting of the Eucharist and the perspective of the recipients of the broadcasts, who were deprived of the possibility of going to church for Easter and thus had to use media broadcasts. |

| 2 | We understand user-generated live video streaming systems to be services that allow anybody to broadcast a video stream in real-time over the Internet (Pires and Simon 2015, p. 225), which means distributing a video feed in real-time to some audience using either a recording camera or a mobile device (smartphone, tablet). Furthermore, it is viewed as common practice that video live-streaming also includes sound (Liljequist 2016, p. 6). |

| 3 | In Poland there is no difference between a city and a town. |

| 4 | The percentages of each parish group in the sample were established on the basis of: Zdaniewicz, n.d. |

| 5 | The classification of individual dioceses according to their territories: 1. north-east: the dioceses of Ełk, Warmia, Łomża, Białystok, Drohiczyn 2. north-centre: the dioceses of Elbląg, Gdańsk, Pelplin, Bydgoszcz, Toruń 3. north-west: the dioceses of Koszalin-Kołobrzeg, Szczecin-Kamień Pomorski 4. east-centre: the dioceses of Lublin, Warsaw-Praga, Siedlce 5. centre: the dioceses of Płock, Włocławek, Łódź, Łowicz, Warsaw, Radom 6. west-centre: the dioceses of Zielona Góra-Gorzów, Poznań, Gniezno, Kalisz 7. south-east: the dioceses of Sandomierz, Zamość-Lubaczów, Przemyśl, Rzeszów, Tarnów 8. south-centre: the dioceses of Kielce, Cracow, Częstochowa, Gliwice, Sosnowiec, Katowice, Bielsko-Żywiec 9. south-west: the dioceses of Wrocław, Legnica, Świdnica, Opole |

| 6 | As regards YouTube broadcasts, the Polish Episcopal Conference Press Office informed that Google had abolished the requirement of having 1000 subscribers for parishes that wanted to broadcast on YouTube during the pandemic (this limit, however, only applies to broadcasts using mobile devices). Although this information was reposted by many websites, it has been officially confirmed by the Google Press Office in Poland (Biuro Prasowe KEP 2020a; ad/Stacja7 2020). |

| Number | Share | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Did the parish broadcast online? | Yes | 626 | 40.8% |

| No | 907 | 59.2% | |

| Total | 1533 | 100.0% | |

| Percentage of Parishes Having Their Own Websites | Overall | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 and Less | 41–50 | 51–60 | 61–70 | 71–80 | 81 and More | |||

| Percentage of parishes broadcasting online | 20 and less | - | - | 100.0% | - | - | - | 100.0% |

| 21–30 | 11.1% | 22.2% | 33.3% | 22.2% | 11.1% | - | 100.0% | |

| 31–40 | - | 45.5% | 45.5% | - | 9.1% | - | 100.0% | |

| 41–50 | - | 12.5% | 25.0% | 12.5% | 37.5% | 12.5% | 100.0% | |

| 51–60 | - | - | 16.7% | 33.3% | 50.0% | - | 100.0% | |

| 61 and more | - | - | - | - | - | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Total | 2.4% | 19.5% | 34.1% | 12.2% | 19.5% | 12.2% | 100.0% | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Przywara, B.; Adamski, A.; Kiciński, A.; Szewczyk, M.; Jupowicz-Ginalska, A. Online Live-Stream Broadcasting of the Holy Mass during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland as an Example of the Mediatisation of Religion: Empirical Studies in the Field of Mass Media Studies and Pastoral Theology. Religions 2021, 12, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040261

Przywara B, Adamski A, Kiciński A, Szewczyk M, Jupowicz-Ginalska A. Online Live-Stream Broadcasting of the Holy Mass during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland as an Example of the Mediatisation of Religion: Empirical Studies in the Field of Mass Media Studies and Pastoral Theology. Religions. 2021; 12(4):261. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040261

Chicago/Turabian StylePrzywara, Barbara, Andrzej Adamski, Andrzej Kiciński, Marcin Szewczyk, and Anna Jupowicz-Ginalska. 2021. "Online Live-Stream Broadcasting of the Holy Mass during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland as an Example of the Mediatisation of Religion: Empirical Studies in the Field of Mass Media Studies and Pastoral Theology" Religions 12, no. 4: 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040261

APA StylePrzywara, B., Adamski, A., Kiciński, A., Szewczyk, M., & Jupowicz-Ginalska, A. (2021). Online Live-Stream Broadcasting of the Holy Mass during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland as an Example of the Mediatisation of Religion: Empirical Studies in the Field of Mass Media Studies and Pastoral Theology. Religions, 12(4), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040261