1. Introduction

Painter and novelist, Michael D. O’Brien (1948–), is among Canada’s leading artists, furthering a tradition of making devotional art in the Canadian context—a tradition which was especially advanced by his friend and mentor, the Ukrainian–Canadian painter, William Kurelek (1927–1977). O’Brien’s art can be found in churches, monasteries, schools, chaplaincies, museums and private collections around the world. Owners or commissioners of his paintings come from diverse backgrounds, including the Missionaries of Charity in the Bronx, New York, the Congregation of Dominican Fathers in Kigali, Rwanda, the Institute of Christian Communities in Montréal, Québec, the Augustinian Fathers in Klosterneuburg, Austria, and beyond. Drawing upon Byzantine icons and photographic realism, cubism and expressionism, paleo-Christian symbology as well as aspects of Inuit art and other traditions, O’Brien uniquely adapts varied art forms to express the spiritual and metaphysical depths of human existence and experience (

Cavallin 2019, p. 9).

In his reflections on the artistic process, O’Brien observes that the artist is called to contemplation. The artist, he says, is a “medium, though not in the sense of a tool or a mechanism or an indifferent conduit;” rather, “he is about a more difficult process: that of making manifest the mysteries and barely perceptible inner beauties of his subject. [The artist] … is a vehicle of perception, an interpreter … a contemplative” (

O’Brien 2019, p. 15). This essay will examine key aspects of O’Brien’s theological aesthetics, contributing new directions to the limited yet growing field of existing scholarship on his work. In so doing, it will show the degree to which contemporary conversations on Christian aesthetics benefit from a greater consideration of the roles which prayer and contemplation play in the exercise of the imagination.

Although O’Brien was a painter long before he became a novelist and essayist, his fiction (especially his series, the

Children of the Last Days) has received greater public attention, earning awards in Canada, the United States, Croatia and Poland. His novels have been translated into multiple languages and enjoy a wide readership in the United States and Canada as well as Europe, especially Eastern Europe. That said, O’Brien studies is in its early years and tends to almost exclusively focus on his novels (

Manganiello 2010;

Maillet 2019;

Hooten Wilson 2019). Thanks to the work of Clemens Cavallin, however, integrated studies of O’Brien’s paintings and writings are on the rise. Cavallin recently wrote the first biography on O’Brien, which has already gone into its second edition, and collaborated on the production and release of the first art catalogue of O’Brien’s paintings. Published in 2019 with Ignatius Press, the catalogue traces O’Brien’s artistic development, his philosophy of the Catholic imagination and his views on the nature of sacred art (

Cavallin 2019, pp. 1–14).

Apart from Cavallin’s recent contributions, the bulk of scholarship on O’Brien’s paintings has been public-oriented, taking the form of journal articles, blog posts, interviews, filmed discussions and spiritual reflections. Many of these reflections or filmed recordings have been made by one of O’Brien’s sons, Father John O’Brien SJ. As just one example, John O’Brien recently recorded a series of Lenten meditations with Salt and Light Television, titled

Journey with the Cross, based on the text of Pope Saint John Paul II’s

Scriptural Way of the Cross. Pairing meditations on the fourteen stations with images from his father’s extensive repertoire of passion paintings, Father O’Brien leads viewers through a recitation of the stations of the cross, allowing the traditional words of this devotion to supply the interpretive framework for his father’s art and vice versa (

O’Brien 2020). Here, we find an approach that is sensitive to the confessional dimensions of O’Brien’s work, to his understanding of art as the fruit of prayerful contemplation of the mysteries of the Catholic faith.

Given that O’Brien’s paintings have received little scholarly attention to date, it is important that they are more fully interpreted in the context of their contributions to theological aesthetics, philosophical theology, spiritual theology and art history. So far, scholarship on O’Brien has tended to focus on his historical context or his own thought, without necessarily placing him within the larger tradition and methods of theological aesthetics and cognate disciplines. This essay attends to this lacuna, offering an extensive overview of his philosophy of devotional art. In so doing, it contributes to, and carries forward, the scholarly conversations initiated and modelled by Cavallin and John O’Brien, highlighting the degree to which spiritual theology deserves more sustained attention in philosophical assessments of the nature and implications of the Catholic imagination. As importantly, this essay examines the degree to which O’Brien’s practices of devotional art and his philosophy of such practices can extend existing scholarship on the Catholic imagination, reminding us of the degree to which the aesthetic and philosophical traditions within Roman Catholicism understand prayer as an irreplaceable resource for imaginative creativity. Having introduced O’Brien’s art and its reception, the next section examines his understanding of the rosary as an invaluable guide for the devotional artist’s imagination. Establishing the centrality of the rosary in O’Brien’s art will then allow us to segue into a lengthier consideration of the distinctly contemplative nature of his theological aesthetics.

2. The Rosary as a Guide for the Imagination

O’Brien’s paintings and novels are imbued with the sense that art is meant to express, and mysteriously participate in, the divine plan of salvation as revealed in scripture. While his art meditates on various episodes from the Old and New Testaments, it often returns to the Gospels as well as Genesis (which chronicles the beginning of life) and the Book of Revelation (which prophesies the ‘end’ or consummation of life and history). To that end, a central focus in O’Brien’s art is the contemplation of Christ’s earthly ministry, especially as expressed in the scriptural meditations supplied by the rosary. For example, a significant art project he undertook in the 1980s and early ‘90s was a series of paintings depicting the mysteries of the rosary. He then published a devotional book on the subject, accompanying each of his paintings with a combination of personal meditations and traditional prayers from the Roman Catholic tradition and incorporating elements of Eastern, Byzantine iconography as well as Western, devotional sensibilities along the way (

O’Brien 1992).

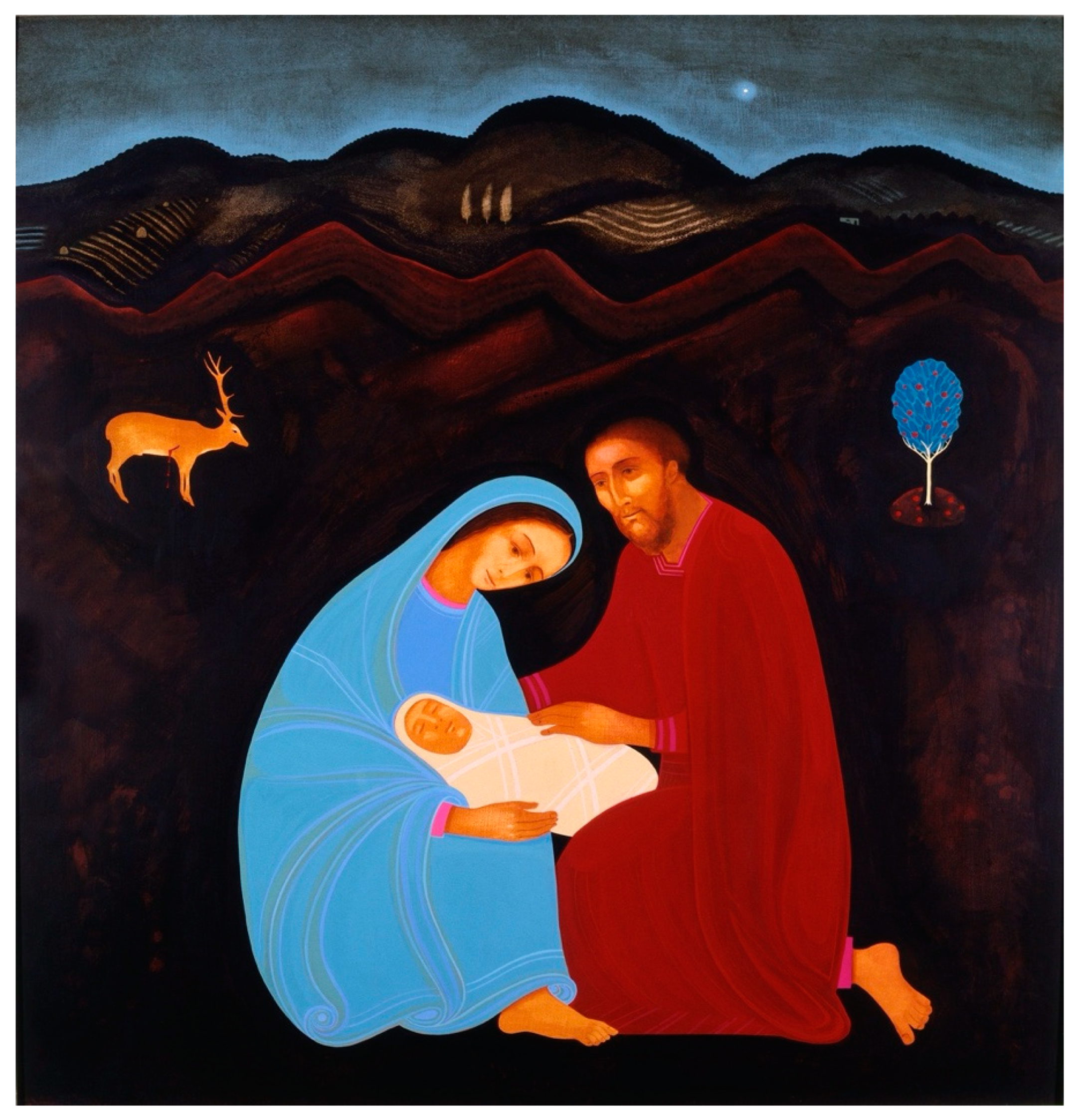

These paintings blend a series of art traditions in a distinctive manner, thereby expressing the dynamic paradox of Christian Catholicity: namely that the Christian message is simultaneously universal (catholic) and particular (personal), relevant to all times and places, operating within but also beyond cultural contexts and values. For instance,

The Nativity (

Figure 1) is a striking example of O’Brien’s unique adoption of centuries of devotional, iconographic art for our times, an adoption profoundly inspired by decades of personal prayer and contemplation. Given its subject matter and blend of varied styles, the painting is at once timely and timeless, drawing together biblical symbolism, the spare style of iconography, and a reserved expressionism in which the dramatic yet sombre landscape of the painting suggests the existential plight of the fallen human condition, while also as firmly hinting at the redemptive work of God incarnate. As with the rosary itself, the painting integrates a network of scriptural passages and images, all with a view to encouraging prayerful meditation on the central Christian mystery: Christ’s incarnation, his entrance into human history.

The painting draws together a cluster of prophetic images from the Old Testament, emphasising Christ’s status as the Messiah. The stag with a pierced side is doubly significant: he foreshadows Christ’s passion and brings to mind the lyric cry of the psalmist who is on the lookout for the Messiah: “[a]s the hart panteth after water; so my soul pant-eth after thee, O God” (Psalm 42:1). The vibrantly coloured fruit tree represents not only the “tree of the knowledge of good and evil” (Genesis 2:17), but also the wood of the cross and Christ’s status as the tree of life (Proverbs 11:30), the living vine (John 15:5). In the distant background, we see a triadic cluster of fir trees swaying in the wind. These trees, of course, represent the three crosses of Golgotha, foreshadowing Christ’s passion and death. In including this allusion to Christ’s future suffering, O’Brien seeks to imaginatively convey the Christian concept of time in which past, present and future meet and are fulfilled in the saving work of Christ’s earthly ministry. This concept of time governs the prayers and patterns of the rosary and often appears as an organising feature in O’Brien’s paintings and novels. The joyful, sorrowful, luminous and glorious mysteries of Christ’s life offers O’Brien an imaginative, analogical trajectory in which the finite (human) and infinite (divine) meet in the midst of both the ordinary and dramatic dimensions of everyday life and living.

This Christian understanding of time is most fully expressed in liturgical theology and the liturgy, itself, as the memorial of, and participation in, Christ’s passion, death and resurrection. As Joseph Ratzinger notes, the New Testament inaugurates a transformative temporal or liturgical consciousness, a “between-time” because Christ defeats death through his own death and offers the hope of everlasting life and the fulfilment of the cosmos through his resurrection, his sacramental, Eucharistic presence, and his promise to come again: “[t]hus the time of the New Testament is a peculiar kind of ‘in-between’, a mixture of ‘already and not yet’. The empirical conditions of life in this world are still in force, but they have been burst open, and must be more and more burst open, in preparation for the final fulfilment already inaugurated in Christ” (

Ratzinger 2000, p. 54). In expressing the “between-time” consciousness established by Christ’s incarnation, O’Brien invites viewers of the painting into their own philosophical or prayerful meditations on the ways in which their personal lives can be transformed by the divine mysteries as represented in the rosary’s scriptural meditations and rhythmic form.

In The Nativity, O’Brien not only uses biblical types or recurring images to reflect on the temporal transformations afforded by the incarnation. He also meditates on the holy family as an example of the kind of contemplation to which the devotional artist is called. Drawing from the iconographic tradition, he depicts the Christ-child wrapped in swaddling clothes and cradled in the intertwined arms of the Virgin Mary and St. Joseph, thereby improvising on the standard biblical account (in which Christ is placed in a manger) to highlight the degree to which divine love and human love worked together, in holy cooperation, to bring about the event of the incarnation. Both Mary and Joseph incline their head towards the Christ child, contemplating his face and serving as models of prayer. Christ is no ordinary child in this painting; his swaddling cloth is also a burial shroud and he has the face of an old man—as is often the case in Byzantine and medieval depictions of the infant Christ. This fusion of infant and wizened man, of birth and death, seeks to express (through the means available to the limited, human imagination) the paradox of God’s entrance into history and the mystery of the hypostatic union.

In

The Nativity, we see the degree to which O’Brien’s art stands in and carries forward a theological understanding of the arts and the artist, an understanding which has been at the heart of Catholicism throughout Church history and especially in Catholic theology and papal teachings throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In particular,

The Nativity places in view the degree to which prayer and painting are inextricably linked for O’Brien: art is the fruit of contemplation, of what could be called a rosarian approach to time and daily life. As with his cycle of rosary paintings as a whole,

The Nativity serves, then, as an example of O’Brien’s visual theology—one which echoes aspects of Pope John Paul II’s reflections on the irreplaceable role and value of the rosary in the life of Christian devotion. More specifically, O’Brien’s artistic depictions of the rosary, of the centrality of the holy family as a model for artists, are saturated with the spirit of John Paul II’s writings on Christian devotion and therefore, at one level, serve as visual correlatives to the late pope’s conviction that the rosary is one of the primary resources for cultivating a contemplative discernment of reality. For instance, in his 2002 apostolic letter,

Rosarium Virginis Mariae, John Paul II writes that “[t]he Rosary belongs among the finest and most praiseworthy traditions of Christian contemplation. Developed in the West, it is a typically meditative prayer, corresponding in some way to the ‘prayer of the heart’ or ‘Jesus prayer’ which took root in the soil of the Christian East” and which “train[s]” Christians from a young age to “pause for prayer” (

John Paul II 2002).

It is beyond the scope of this introductory essay to do justice to the many links between John Paul II’s theological aesthetics and O’Brien’s; however, it is an area which deserves significant attention and I hope it will feature in new directions taken in scholarship on O’Brien in the near future. That said, it is important to note the sympathies between both thinkers in order to show the degree to which O’Brien’s art and thought draw deeply from the tradition of Catholic theology, especially the Catholic thought of the twentieth century (which has been profoundly shaped by the insights and papacy of Pope John Paul II). In the next section, we will consider the degree to which contemplation is at the heart of O’Brien’s theological aesthetics. In so doing, we will gain a better sense of the way in which he understands the imagination—and, by extension, the practice of the arts—to be inherently religious.

3. Called to Contemplation: O’Brien’s Theology of the Artist’s Studio

Reflecting on the history of art, O’Brien writes that it is “inherently religious” (

O’Brien [1997] 2017, p. 62). From the pre-historic cave paintings in Lascaux to the present day, he sees artists searching for the transcendent, for a meaning that responds to personal, human desire and yet reaches beyond it (

O’Brien [1997] 2017, pp. 60–65). O’Brien developed this perspective more explicitly in his years as a practicing artist. However, he shares that an inkling of the religious dimension to art and within the workings of the imagination first emerged in his childhood—especially in the years he and his family spent living in a “small Inuit (Eskimo) village” in Canada’s high Arctic in the early 1960s (

O’Brien [1997] 2017, p. 62). O’Brien’s memories of First Nations art, especially Inuit carvings of animals, humans and Inuit mythology, left a deep and lasting impression on his imagination. In particular, he recalls being struck by the work of an elderly Inuit woman who used to sit in her tent along the shore of the Arctic Ocean, resting on “an empty packing crate scavenged from the Hudson Bay outpost” and carving animals of “heart-stopping” beauty by firelight (

O’Brien [1997] 2017, p. 62). In her stone carving called

Man Wrestling with Polar Bear, the young O’Brien intuited a deep understanding of the existential (not just historical) aspects of the human condition: “[i]n the North”, he writes, “men do not wrestle with bears. In such encounters men always lose. This image was a solid metaphor of the interior wrestling which is our abiding condition […] It was pondering existential questions in the only language available to her, and it was for that reason”, he concludes, “inherently religious” (

O’Brien [1997] 2017, p. 62). For O’Brien, art’s inherent religiosity is especially bound up, then, with questions about the nature, conditions, and calling of the human person, and, in turn, it is fed by the artist’s sensitivity to the “mysterious roots of life itself” (

O’Brien [1997] 2017, p. 62). There is therefore a profound affordance of religious value in the very making of art, irrespective of the creedal or faith position of artists (

Hopps 2020, pp. 79–94).

Although O’Brien’s writing on the inherently religious nature of the arts emerges in some of his essays and novels, he tends to be more explicitly Christian and devotional in his theological aesthetics. While the expressly devotional standpoint of his writing is one of the most attractive features of his approach to aesthetics, his recollections of his childhood in the Arctic show the degree to which he is highly capable of implicit and more strictly philosophically oriented approaches to aesthetics. At times, scholars have expressed the desire for O’Brien to extend this more implicit mode of approach to his aesthetics, given how perceptive it is when it does emerge and, as importantly, given how much it would open up his art to people standing outside of Christianity. For those who appreciate O’Brien’s occasionally subtler approach, they may find the paintings he classifies in the Ignatius art catalogue as ‘implicit’ or ‘reflective’ of particular interest (

O’Brien 2019, pp. 119–35, 137–67). That noted, O’Brien’s sees his art in clearly vocational terms and has discerned the call to address his audiences from the express standpoint of belief, noting that Christian artists possess a particular responsibility to reveal the degree to which the innate longings of the artist are fulfilled in the mystery and person of Christ—who, in his redemptive work, is the artist par excellence (

O’Brien 2019, pp. 65–80). For O’Brien, then, the practical and philosophical elements of imaginative creativity are most fully formed and informed by scripture, Christian doctrine and divine revelation.

Indeed, O’Brien has recently shared that it is only upon his (re)conversion to Christianity that he discovered his abilities as an artist and saw in this discovery a call to express his conversion in artistic forms (

O’Brien 2019, pp. 17–18). In his conversion, he discerned in Christian revelation and doctrine a striking realism (as opposed to a vague set of ideals), which gave him a greater sense of meaning and purpose: “My conversion to Christ…was a pure gift from God”, he confesses. “It was sudden, totally unexpected, instantaneous, like St. Paul’s on the road to Damascus. It was a radical shock … and a revelation that everything the Church and Scripture had taught about God was, in fact,

reality” (

O’Brien 2019, p. 19). As we can see from this reflection, O’Brien’s art is, among other things, an outworking of what scholars have called the dogmatic or doctrinal imagination. As I have discussed elsewhere, Dorothy L. Sayers and Timothy Radcliffe are among those theologians who have classified “[t]he authentic ‘dogmatic imagination’ as [that which] … explores the articles of Christian faith in order to teach, to heal, to expand the horizons of what can be thought of, and hoped from, history in light of Christ’s saving work” (

Lamb 2020). To O’Brien’s mind, an imagination inspired by Christian doctrine is in possession of expanded horizons of hope because it can seek and find the presence of the triune God (who is “in fact,

reality”) in the rhythms, routines and events of daily life. Such an understanding is on display in O’Brien’s painting,

The Studio (

Figure 2), completed in 2016. The painting also supplies a theology of the arts in which contemplation of divine things is seen as being among the most crucial elements of artistic praxis.

Incorporating a range of symbols, The Studio focuses on the process of painting and also considers the role of prayer in the making of art; it is therefore an intriguing fusion of the meta-critical with the metaphysical, of the self-reflexive with the self-transcending. That is to say, the painting understands the natural and supernatural, technique and prayer, in light of each other. Tubes of acrylic paint, like the ones O’Brien used to produce this very painting, are placed in clear view, located close to his other tools (water, brushes, an easel). There are a series of different light sources. From a naturalist perspective, the light of the moon (which classically represents the artist’s imagination) illuminates the studio. However, the golden icon of St. Luke and the white dove descending over the artist’s easel suggest additional (as opposed to alternative) light sources. Here, prayer and nature work in cooperation. The painter’s easel is cruciform in shape, with the Latin inscription ‘INRI’ (‘Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Judaeorum’) mostly in view, spread across its horizonal axis (John 19:19). O’Brien transforms the idea of the artist’s wooden easel, seeing it as not only a functional aid to the creation of the artwork but also an ennobled tool, a material good which doubles as a conduit of grace, a reminder of Christ’s passion, death and resurrection.

O’Brien’s depiction of his own studio draws from the long Christian tradition. As Leonard Boyle OP noted, the early Christians, and the medieval artists after them, discerned cruciform patterns everywhere; in their view, the cross “was, indeed, the axis of the universe itself, and drew everything to its centre” (

Boyle 1989, p. 30). For O’Brien, artists are brought into closer contact with God by seeing indications of the incarnate Christ, and of the cross which leads to resurrection, in each step of the creative process. Commenting on the relationship between artistic contemplation and artistic praxis, he observes that “[t]he artist must be tireless in perfecting his practical skills and knowledge of the art, for without the discipline of craftsmanship, the vision will be indistinct and may even fail altogether. Grace builds upon nature, says Aquinas, and thus the artist of faith must be as dedicated to prayer as he is to his tools” (

O’Brien 2019, p. 16). To illustrate this point even further, O’Brien includes an explicit depiction of the Holy Spirit (who is more subtly introduced in some of his other devotional works) to drive home the invaluable roles that both divine inspiration and prayer play in the making of art.

Hovering in the upper left-hand corner of the painting, the Holy Spirit is represented as the source of imaginative ingenuity. Throughout the history of Christian art, the Holy Spirit has been described as the muse par excellence; this is discernible in classic, Christian artists—like Fra Angelico and Dante—as well as more recent and contemporary art forms, such as the nature sonnets of the Victorian poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins SJ, Toni Morrison’s literary criticism, and, of course, O’Brien’s own devotional art. As with the cruciform shape of the easel, the inclusion of the Holy Spirit serves as a reminder that artistic creativity, as with human life, is first and foremost made possible through divine gift; it does not originate from the resources of the artist only. If anything, the artist is a co-operator in the project of divine creativity, imitating the creative activity of the Trinity which loved the cosmos into existence. As with Jacques Maritain, who viewed the artist as a noble but ‘poor god’ (able to imitate and associate rather than originate

ex nihilo), O’Brien sees the work of the artist as always already derivative, a response to the creation of the world as revealed in Genesis (Maritain 1953). In this way, the presence of God the Father is also implicit in this painting—especially given that O’Brien views the artist as a “co-creator”, as someone who is called to prayerfully respond to and imitate God’s own original creativity (

O’Brien 2019, p. 16).

The artist’s studio is, then, a place not unlike a contemplative’s cell; it is a space in which the skilled work of the artist and the tools of his or her trade are means through which the words of scripture and the Catholic tradition are weighed and expressed. For, according to O’Brien, the imagination that is responsive to Catholic doctrine and teaching will draw strength and inspiration from contemplation and prayerful discernment. The artist, he observes, is called to be “ceaselessly concerned with the authenticity of the work and the good of those who will one day gaze upon it […]” (

O’Brien 2019, p. 16). As such, the artist (like the icon writer) is meant to be attentive to “the demands of

ora et labora” (

O’Brien 2019, p. 16). “This is no small task … no small vocation” he admits (

O’Brien 2019, p. 16). Drawing from Maritain’s theological aesthetics, O’Brien proposes that the artist’s primary calling is neither popularity nor success. Rather, it is the call to love, to become a saint: “For most of us,” he writes, “the path is one of long, hard labors combined with a spirit of exploration and, above all, a spirit of love, which is the means and motive of the growth. At the core of all genuine love is the willingness to sacrifice, to die to oneself so that others may live […]” (

O’Brien 2019, p. 16). Here, O’Brien is influenced by the sensibilities of the contemplative Christian tradition, especially the monastic one. In his theological account of the imagination, divine inspiration is not some flash from above but, rather, a mysterious unfolding (much like the phenomenon of life, itself): the “creative process”, he observes, “is an experience of what I believe is the ‘co-creative’ mystery, that is, grace working together with my natural talents. For me, fiction is neither entirely nature nor entirely grace. It’s neither purely rational nor purely intuitive” (

Olsen 2020).

It is no wonder, then, that O’Brien chose St. Luke as the subject of the icon depicted in

The Studio. Luke the evangelist is the patron saint of doctors and artists, reputed to have painted the first image of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ child. The Gospel of Luke emphasises Christ’s evangelization of the Gentiles; it therefore stresses the universality or catholicity of Christ’s redemptive work. By extension, as the patron of artists, St. Luke represents arts’ universal ability to draw imaginations from around the world and throughout history towards the transcendent. The significance of St. Luke for artists is also a theme in O’Brien’s novels. For example, in

Theophilus, he imaginatively explores how Luke’s witness to belief in Christ sets his agnostic, adoptive father on an existential pilgrimage towards Christian belief (

O’Brien 2010). In featuring St. Luke,

The Studio testifies to art’s ability to speak to the inner-most depths of those with or without faith, drawing them toward deeper encounters with the mysteries of existence and experience (

O’Brien 2010, pp. 16–18). That noted, the often explicit way in which O’Brien incorporates spiritual imagery into his devotional paintings tends to make his art most immediately accessible to Christian believers or those with some religious or biblical literacy (something which, increasingly, cannot be taken as a given).

Having examined the centrality of prayerful contemplation in O’Brien’s philosophy of art, the next section situates his thought on the Catholic imagination (although this is a term he does not tend to use expressly) within the wider context of theological aesthetics. In so doing, it emphasises the degree to which O’Brien offers an integrative approach. He not only draws from an astonishing number of art forms and styles in his paintings. He is also as explorative and wide-ranging in his philosophical engagements with the Catholic theological tradition, covering and integrating centuries of Christian devotion and theological expression.

4. O’Brien and the Catholic Imagination

Imaginative responses to Catholicism date back to the early Christian era, evidenced in the writings, material culture and liturgical practices developing during that period. Throughout church history, theologians and church councils have clarified the status of the arts within the life of faith and culture. Imaginative responses to Catholicism have therefore been ongoing since the days of the early Church, and such responses began to receive systematic assessments in medieval, philosophical theology (

Haldane 2013, pp. 25, 31–35). As John Haldane reminds us, the nature and “practice of art was a source of significant reflection within medieval thought”, and the “representational arts” were carefully assessed in light of scripture, conciliar theology, and the wider tradition of Christian thought found in the Greek Fathers and the Latin West (

Haldane 2013, pp. 25–27). However, the “concept of the aesthetic” as it is often used today principally stems from eighteenth-century thought, especially “philosophical psychology and investigations into judgments of taste” that are invigorated by “the question of how estimations of beauty, though expressing a personal response to nature or art, nevertheless seem to lay claim to truth” (

Haldane 2013, p. 25). “[M]odern aesthetics” is therefore “a branch of philosophy of mind and theory of value,” whereas during the medieval period aesthetics “belong[ed] to philosophical theology” (

Haldane 2013, p. 25). It is especially thanks to Hans Urs von Balthasar and his recent inheritors that recuperations and extensions of the medieval understanding of art as a resource for theology and prayerful contemplation are under way, opening up a series of important conversations within Roman Catholic theology and across other Christian denominations as well. It is also thanks to Balthasar’s work, especially his magnum opus,

The Glory of the Lord: Theological Aesthetics (1961–1967), that the concept of ‘the Catholic imagination’ has increasingly surfaced in recent decades and features in theological aesthetics, philosophical theology and literary criticism in particular (

Tracy 1981;

Greeley 2000;

Pfordresher 2008;

Carpenter 2015).

Balthasar’s contributions to theological aesthetics have, as we know, especially influenced Pope John Paul II (who elevated Balthasar to the cardinalate), and are discernible in his theological writings, such as his pastoral letter to artists, delivered at the Vatican on Easter Sunday, 1999. In this pastoral address, John Paul II reminds fellow artists that their “special vocation” is most fully realized through prayer (

John Paul II 1999). “The more conscious they are of their ‘gift’”, he writes, the more artists “are led … to see themselves and the whole of creation with eyes able to contemplate and give thanks, and to raise to God a hymn of praise. This is the only way for them to come to a full understanding of themselves, their vocation and their mission” (

John Paul II 1999). O’Brien’s own theological aesthetics is greatly indebted to both John Paul II and Balthasar and is best understood as part of the recovery and development of medieval, theological aesthetics which has been ongoing throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. Bearing this in mind, the rest of this section will consider key aspects of O’Brien’s views on the role of art in the life of devotion and the way in which his philosophical approaches enrich the concept of ‘the Catholic imagination’, as it is currently discussed today.

O’Brien has written extensively on artistic and theological influences in his work—ranging from the pre-historic, Cro-Magnon artists who decorated the caves of Lascaux to Christopher Dawson, Jacques Maritain, Catherine Doherty, von Balthasar and William Kurelek, among others (

O’Brien [1997] 2017). However, his cultivation of a Catholic imagination, of a contemplative way of seeing the world, also stems from decades of meditating on the work of Pope John Paul II. In his “Letter to Artists” (similar to aspects of Pope John Paul II’s own), O’Brien sees the cultivation of a Christian imagination as a vocation, as the response to a divine calling; in this sense, art is the fruit of conversations with God and the practice of art itself is that of speaking with and about God. O’Brien’s theological aesthetics is, then, deeply personal in character, and can be understood, to a certain extent, as an extension of the Christian personalism which flowered throughout the early decades of the twentieth century, principally in the phenomenological work of Max Scheler, Edith Stein, Dietrich von Hildebrand, and John Paul II, among others (

Lamb 2016).

Specifically, for O’Brien, imaginative expressions of Christianity are rooted in a personal exchange between the self and the Triune God: “[t]here is always a mystery regarding each person’s vocation in the works of the Lord,” he writes. “… [God’s] creation is not a machine but rather a vast work of art […] ‘We are God’s work of art’, says St Paul [Ephesians 2:10]. Growth in the vocation [of the artist] is usually a series of countless small steps of faith, usually blind steps, because what God wants to accomplish most in us is the increase of absolute trust in him, not so much successes […] I believe his primary will is accomplished and is always more fruitful, to the degree that we have agreed to be very little instruments in his hands” (

O’Brien 2018). Here, O’Brien distinguishes divine creativity and Christian art from machine-based or mechanistic modes of production. He makes this distinction to stress the degree to which a Catholic imagination is meant to see persons, nature and the created order as dignity-bearing values, instead of ‘means’ to be exploited or worshiped as idols (

O’Brien [1997] 2017, pp. 79–80). For O’Brien, a persistent temptation for the artist is the forgetting of the call for a relationship with God and others; such a forgetting leads to the worship of lesser goods (talent, success, ingenuity) and becoming obsessed with one’s own creative capacities. The artist’s imagination therefore requires training, detachment and transformation through contemplative prayer and receptivity to grace.

O’Brien’s art and theological writings often address the theme of temptation towards idol worship (of one sort or another), and one of his most extensive essays on the Catholic imagination, entitled “Historical Imagination and the Renewal of Culture,” reflects on the significance of the theological debates held between iconoclasts and iconodules in the eighth and ninth centuries, the Reformation, and during our own times (albeit in subtler forms) (

O’Brien [1997] 2017, pp. 66–76). The commandment against the making of images in the Old Testament was, according to O’Brien, part of a providential plan to lead people away from attempts to live according to their own terms: “[t]he Old Testament injunction against graven images was God’s long process of doing the same thing with a whole people that He had done in a short time with Abraham. Few if any were as pure as Abraham. It took about two thousand years to accomplish it, and then only roughly, with a predominance of failure. Idolatry was a very potent addiction. And like all addicts ancient man thought he could not have life without the very thing that was killing him” (

O’Brien [1997] 2017, p. 66).

From God’s calling of Abraham to the events leading to Christ’s incarnation, O’Brien discerns the gradual emergence of a theological aesthetic, a way of seeing and expressing the world according to right worship as opposed to idolatry. Jean-Luc Marion, Aidan Nichols and Rowan Williams, among others, have also reflected at length on the respective places of the icon and idol in the history of Christian aesthetics (

Marion 2004;

Nichols 2007;

Williams 2003). As with O’Brien, they share the understanding that the imagination at the service of devotion calls for a kind of self-renunciation so that art itself becomes, as Williams puts it, not just the production of “a striking visual image” but rather the “open[ing] of a gateway for God” (

Williams 2003, p. xvii).

Despite O’Brien’s conceptual sympathies with Williams et al., it is important to stress that his views on the subject not only grow out of philosophical reflection and prayer but, as importantly, from the lived experience of making and producing art—an experience which he proposes demands a constant renewal of commitment to conversion of heart through meditation on scripture, the Christian tradition and the lives of the saints (

O’Brien 2013). For O’Brien, this is because the artist deals with the material world in a very distinct and particular way and is therefore called to undergo the same pilgrimage of spiritual growth chronicled in the Old and New Testaments, a pilgrimage which leads towards the contemplation of God in the beatific vision. Such a contemplation begins on earth and in the Christian tradition culminates in heavenly adoration of the triune God who is revealed by Christ. Christ’s incarnation therefore supplies the artist’s imagination with an agapic as opposed to self-absorbed disposition towards the world and other persons. “Because the Lord had given himself a human face, the old injunction against images [can] … be reconsidered,” O’Brien writes, and the gradual emergence of a Christian visual culture marks the gradual, spiritual renewal and transformation of artistic imaginations throughout history (

O’Brien [1997] 2017, p. 69). This process of spiritual renewal constitutes the Christian understanding of salvation history and features as a recurring theme throughout O’Brien’s paintings. For example, in

St. Francis Embracing the Leper (

Figure 3), O’Brien explores the degree to which Christ’s incarnation, and especially his passion, death and resurrection, transforms how the artist sees the value of other people—especially those on the margins of society who suffer with difficulties we instinctively wish to avoid or hide.

Following St. Francis’ example, O’Brien represents the leper

in persona Christi (‘in the person of Christ’), thereby expressing a profound understanding of the dignity of human suffering when it is placed within the context of Christ’s redemptive self-sacrifice. Incorporating the tradition of early Christian iconography, in which the left and right sides of Christ’s face are made asymmetrical (so as to indicate the hypostatic union), O’Brien suggests that through the leper’s disfigurement and suffering the love of the God-man and the mystery of the incarnation, itself, are uniquely found. In this way, the dignity of the human person, irrespective of circumstances or conditions, is made explicit. In the background of the painting, we spot a reference to calvary, which is at once the site of Christ’s profound suffering and the gateway to resurrection and spiritual transformation. It also serves as the key moment in salvation history, allowing Francis’ encounter with the leper, centuries later, to take on new significance and depth. Given all this, the painting offers us a window into the ways in which the lives of the saints, throughout history, witness to and “manifest… the life of Christ in countless forms”, making the “hidden face of divine love … visible” (

O’Brien 2019, p. 103).

As with devotional icons,

St. Francis Embracing the Leper serves as a mode, then, of visual theology, communicating the degree to which Christ’s incarnation offers the artist a new way of viewing the world, one in which he or she learns to reverence and care for creation as opposed to dominating or worshiping it. The figure of St. Francis is the exact opposite of the ego-driven artist who has rejected the spiritual dimensions of existence. Often depicted as a kind of holy fool in literature and art, St. Francis is characteristic of a ‘type’ of character or personality O’Brien presents and represents in his paintings and novels. For instance, in

The Fool of New York City,

O’Brien (

2016) orchestrates a series of important encounters between a disenchanted, post-modern artist (or aesthete), who is suffering from amnesia, and a quiet, giant of a man who lives like a humble Franciscan in the concrete jungle of New York city, transforming the lives of those who encounter him through his radical commitment to the beatitudes. Throughout this novel and O’Brien’s paintings more generally, Christ and Christ-like figures abound, serving as representations of agapic, contemplative love in the midst of the world and its problems.

It is particularly in his imaginative depictions of Christ and Christ-like behaviour that O’Brien offers contemporary, scholarly conversations on the Catholic imagination concrete models of the integration between thought and action, philosophy and virtue, imaginative expression and the ‘art of living’—to borrow a phrase from Dietrich von

Hildebrand (

2017). Having considered the close relationship between contemplation of Christ and worship in O’Brien’s theological aesthetics, the final section of this paper examines the degree to which O’Brien’s contemplation of the cross enriches conceptualisations of the Catholic imagination.

5. O’Brien’s Christological Aesthetics

In O’Brien’s theological aesthetics the event of the incarnation gives the innate religious sensibility of the artist a wider horizon. The incarnation declares that God is not only provident but personal; he is intimately involved in the lives of each of his creatures. As importantly, Christ’s incarnation declares that the natural and supernatural are not separated by a major gulf; rather, they are merged together. The finite and infinite are joined; the horizontal and vertical, the imminent and transcendent are met in Christ’s hypostatic union. This point is, of course, central to what Balthasar argues in The Glory of the Lord but O’Brien’s own meditations on the implications of the incarnation for the arts are helpful and timely contributions to the growing conversations on the Catholic imagination—especially when it comes to seeing an example of how theory and practice, aesthetics and the making of art, can meet and mutually inform each other.

For O’Brien, the Eucharist and participation in the liturgy and the sacramental life of the Church are irreplaceable resources for the imagination. Christ’s entrance into history and his redemptive work inaugurates the sacrament of the Eucharist and it is this mystery of divine self-gift which, according to O’Brien, unites “word, image, spirit, flesh, God and man” into “one” community of believers (

O’Brien [1997] 2017, p. 69). Through the institution of the Eucharist, Christ draws all believers together in a fellowship rooted in divine self-donation, a gift finding its fullest expression in the liturgy of the Eucharist (

O’Brien [1997] 2017, pp. 69–80). In the liturgy, the entire drama of Christ’s life is remembered, and in this remembering the participating faithful are drawn into communion with Christ and each other. This key aspect of the liturgical theology of the Roman Catholic Church reoccurs throughout O’Brien’s art, both explicitly and implicitly. Given this, O’Brien’s philosophy of sacred art is especially expressive of two of the three kinds of “mystical experience[s] within the Christian church” as identified by Oliver Davies (

Davies 1988, p. 4). According to Davies, the divisions are as follows: first, “a form which we may call the mysticism of the sacraments and of the liturgy”; second, a ”Christocentric spirituality which is based upon imagery that is sometimes biblical and sometimes secular, and upon revelation … [which] in its more intense form [may include] visions in which a supernatural dimension entirely effaces everyday reality”; and, finally, the transcendence of imagery and an encounter with “the ‘darkness’ and the ‘nothingness’ of the Godhead itself in a journey which leads the soul to the shedding of all that is superfluous … to God” (

Davies 1988, p. 4).

O’Brien’s paintings and novels do occasionally and paradoxically involve the “transcendence of imagery” and it is an element of his aesthetics which could benefit from even further consideration in scholarship. In so far as his theology of aesthetics attends to the dark night of the soul, it usually finds fullest expression in his novels. However, there are instances when the transcendence of images is, paradoxically, a crucial subject of his paintings: note, for instance, his tendency to situate figures in dark, earthy or womb-like settings in an effort to image the image-lessness to which the pilgrimaging soul will be subjected. Likewise, in paintings such as

Temptations in the Desert (2002), Jonah (2001),

St. John the Baptist in Prison (2001),

The Prophet Elijah (2000) and Exodus (1982) we find him experimenting with a striking variety of styles, colours and expressions in order to communicate the mystical movements of the human soul, movements which transcend the very forms of expression which seek to talk about them in some way. These exceptions aside, O’Brien’s art and reflections on art principally focus on the sacramental and Christological forms of mysticism, in which the inclusion of images is seen to help occasion closer contact with God incarnate. This positive theology of imagery is a central and abiding presence in O’Brien’s paintings, from his earliest work in the 1970s to the present, and accounts for the wide-ranging series of passion paintings he has produced over the decades. For example, in his painting,

Christ and Adam (from the early 1990s), we see O’Brien’s Christological imagery yoked to a hope-filled, cruciform aesthetic (

Figure 4).

Christ and Adam meditates on Adam’s status as a precursor to Christ, the God-man, who is the ‘New Man’ or ‘New Adam’ and restorer of the union between God and humanity, a union which Adam and Eve damaged through the fall (Genesis 1: 1–3). By his life, death and resurrection, Christ becomes the New Adam who transforms the original Adamic relationship with God. The sombre, earthy palette of the painting invokes Adam’s creation out of “the dust of the ground” and Christ’s incarnation (Genesis 2: 7). Although Christ bears his stigmata and the wounds of his passion, he is the one supporting a weakened Adam. As the wounded healer, Christ enters into solidarity with Adam’s fallen condition, drawing him into new life.

The painting brings together a constellation of images which reference Christ’s suffering on earth. Once again, O’Brien’s signature inclusion of three crosses in the background reefer to Christ’s passion and, due to their triadic clustering, also gesture towards the Trinitarian nature of God (as we recall, this triadic clustering was also present in O’Brien’s The Nativity and, indeed, is found in most of his paintings). Christ and Adam therefore transposes 1 Corinthians, chapter 15, in which St. Paul compares and contrasts Adam with Christ, reminding the faithful of Corinth that Adam’s fall led to original sin and the punishment of death but Christ’s resurrection undid the power of death, thereby transforming the meaning of suffering and reuniting fallen humanity with God: “For by a man came death, and by a man the resurrection of the dead. And as in Adam all die, so also in Christ all shall be made alive” (1 Corinthians 15: 21–22).

Given all this, the painting views the cross with reverential joy, seeing it as not just a brutal death or poison but also a cure: it is the holy pharmakon, as it were. In so doing, it celebrates the central paradox of Christian faith: the cross leads to new life. O’Brien is therefore not satisfied with just two references to Christ’s passion. He not only includes three crosses and details of Christ’s glorified wounds (note how the dotted imprints of the crown of thorns are ennobled in this painting, appearing like a scarlet constellation of stars on his forehead); he also incorporates the top portion of a saltire cross, upon which Christ props a weakened and world-weary Adam. In interweaving multiple depictions of the cross, O’Brien deftly incorporates an element of devotional imagery which emerged during the fourth and fifth centuries, following on from the Edict of Milan (313 CE), but which gained in momentum and popularity throughout the Middle Ages, particularly in Western churches. Early and late medieval art (frescos, mosaics, icons, acrostic poems, Gothic and Romanesque churches, and mystical writings or ‘shewings’) were encoded with a multiplicity of cruciform patterns and representations of the cross and the instruments of Christ’s passion. For example, in the famous, twelfth-century apse mosaic located in the Basilica of San Clemente al Laterano, in Rome, Italy, the cross is depicted as the Tree of Life. Throughout the mosaic, there are a series of “allegorical repetition[s]” of the cross motif, including “the Sign of the cross itself: the monogram of Christ (chrismon) enclosed in an elliptical disc (clipeus) to symbolise the victory won over death by the death of the Cross” and, among other symbols, the lamb that was slain (a reference to Christ’s crucifixion in Isaiah and the Book of Revelation, respectively) as well as coded depictions of the Eucharistic feast which is the memorial of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross (

Boyle 1989, p. 30).

The cruciform aesthetic found throughout the Christian art tradition is so prominent and celebrated that it led Erich Przywara SJ to observe that “the ‘scandal of the folly of the Cross’ appears as the origin, measure, and defining goal of Christian sacred art” (

Przywara 2014, p. 554). As I have noted elsewhere, it is in observing and tracing this cruciform pattern in the Catholic imagination that Przywara finds in “the cruciform vision of the world [the fact] that Christianity offers an access to hope that can withstand human suffering [and] … reminds us that the witness of Christian art, throughout church history, upholds the cross as a sign of hope, contradicting the various fears […] endured throughout the course of history” (

Lamb 2021, p. 19). In O’Brien’s art we discern the kind of cruciform aesthetics admired by Przywara and informing Roman Catholic philosophical and theological engagements with aesthetics throughout Church history. As importantly, we find O’Brien often fusing elements of the Byzantine iconographic tradition with aspects of realism in an effort to communicate the transcendent and immanent nature of Christ as fully God and fully man. This fusion is uniquely accomplished in his art and shows the degree to which his commitment to Christian doctrine widens (as opposed to limits) imaginative expression.

Before turning to the conclusion, it would be remiss if we did not pause to stress O’Brien’s understanding that the cross is meaningful because it is the gateway to the resurrection. This is why, even in his starkest meditations on Christ’s passion, his paintings tend to include glimpses or foreshadowing of the resurrection. This is accomplished in various ways, such as his depiction of Christ’s wounds as stars or jewels, as seen in

Christ and Adam. In this way, O’Brien’s Christological aesthetics is keyed into the register of hope. Given this, his art exhibits what Christopher Wojtulewicz would call “eschatological transparency”, a witness to the future glory of humanity resurrected. Speaking of devotional art (this side of heaven), Wojtulewicz writes: “[w]hen we see in the mirror the face of God, we do see it, but without the transparency that belongs to resurrected life, and when we try to express what we see, or merely the experience of seeing it when we do see it, we suffer the inability to clothe it in words or express it fully” (

Wojtulewicz 2016, p. 8). Despite the vivid and concrete imagery which characterizes most of O’Brien’s art (and therefore places him firmly in the first two ‘ways’ of mystical experience identified by Davies), it is nonetheless clear that his artwork, in true iconographic style, always already points beyond itself, aware of the limits of the artist’s imagination to convey the depths of the mysteries it nonetheless invites us to contemplate.