1. Introduction

Those who declare that they do not identify with any institutional religion are the “religious” segment that is growing the most in Argentine society. From 1.63%, as recorded in the 1960 National Census, to 18.9% in 2019 (

Mallimaci et al. 2019), it grew by 1059% over half a century, becoming the first “religious” minority and surpassing even the Evangelicals, who represent 15.3% of the resident population in Argentina.

The sociological analysis of this group does not only imply characterizing its age, social and geographical composition; it also implicates taking a look at the transformations in the religious map and the mutations in beliefs, practices, and adherences of individuals in contemporary Argentina.

Ever since the social sciences of religion revised the classic postulates of the theory of secularization that predicted the privatization and even the disappearance of religion in modern life (

Berger 1967), the analysis has been oriented toward understanding the new religious movements. In the last quarter of the twentieth century, the processes of pluralization of the religious field concentrated the attention of sociologists and anthropologists of religion. In this context, research on evangelical growth stood out (

Mariano 2004;

Wynarczyk 2009;

Seman 2010;

Algranti 2010;

Carbonelli 2011;

Mosqueira 2016).

In line with the renewed interpretative frameworks that uphold the mutual implication between modernity and religion (

Eisenstadt 2000), the focus of interest of the specialized academics aimed to unravel the transformations in religious beliefs and practices, as well as in the ways of relating to the sacred. This paradigm, which undoubtedly broadened the research paths in the contemporary social sciences of religion, also functioned at first as an

epistemological obstacle (

Bachelard 2000) to recognize other phenomena that emerged simultaneously, such as the process of subverting the links between individuals and their institutions of belonging, leading to estrangement, disaffiliation and less effectiveness in the institutionalized regulations and mediations (

Esquivel 2020). The religious field also reflects this situation, showing both a religious “self-accounting” (which can be summarized in believing in one’s own way) and a greater religious indifference. Therefore, it presents a much more diverse picture, with broken institutional loyalties as a backdrop. It is in this cultural territory that we must place and analyze those who, in a very preliminary way, we can identify as “without religion”.

Since this is an area that has been little explored by the social sciences of religion in Latin America

1, it is necessary to formulate a range of questions as a starting point for research.

What are the socioeconomic, demographic, and residential characteristics of the religiously unaffiliated people? Does it express a temporary situation in the transit from one religion to another, or does it show signs of permanence? What has been the family environment in which they have been socialized in terms of religiosity? Did they grow up in an environment in which religion played a relevant role or, on the contrary, was religion not present at that stage of their lives? Do their trajectories reveal instances of adherence and belonging to some institutionalized religion, or are they characterized by rejection and/or alienation from any expression of religiosity? In other words, are we facing processes of active disaffiliation or rather of religious indifference resulting from a family socialization detached from any religious attachment? Is this a positive choice or does it reflect an inadequacy in the face of existing religious options? These concerns aim to elucidate the current density and projection of this portion of Argentine society.

Then, what do people “without religion” believe in and practice? What are their values and belongings, beyond the strictly religious ones? Asking ourselves about the beliefs and practices of this segment of the population will allow us to understand if it is a process of distancing oneself from religious institutions without necessarily losing one’s religiousness—believers without institutional religion—or if it directly reflects situations of religious unbelief—the atheists and the agnostics. Underlying the differentiation between beliefs and affiliations is an analytical strategy that is decisive for interpreting this sociological phenomenon with greater depth and precision.

Finally, what are the similarities and differences between those who maintain their condition as believers even if they do not channel it through institutionalized frameworks and those who identify themselves with a religion but in a nominal way without a daily religious insertion and practice?

With the aim of contributing to the construction of a sociology of those “without religious affiliation”, we will go through these research questions in order to identify different profiles that coexist within a social segment whose ranks have grown systematically.

In 2019, the Society, Culture, and Religion Programme (CEIL-CONICET) carried out the Second National Survey on Religious Beliefs and Attitudes in Argentina, which was led by a coordinating team in which I was a member

2. The research was based on a probabilistic survey. The study universe was made up of the population of the Argentine Republic aged 18 years or more, living in localities or urban agglomerations with at least 5000 inhabitants. A total of 2421 cases were selected through a multistage sampling. The first stage, with 89 localities/agglomerates as primary sampling units, combined stratification (according to region and size of localities) and selection of urban agglomerates within the stratum by probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling. In the second stage, the selection of the sampling units (sample radius) within the selected localities was made by random systematic sampling (ordering by socioeconomic level indicators) with PPS (attending to the amount of population) and equal assignation by census radius. Once the areas of work were chosen, the systematic survey and selection of private dwellings was carried out (third stage). For the selection of the final sampling units (fourth stage), sex and age quotas were used according to population parameters. We worked with a margin of error of +/− 2% for a reliability level of 95%. Since this is a multistage probability survey that combined stratification by region and city size and selection by systematic randomization (with PPS), the data can be extrapolated to the general population considering the margin of error.

2. Toward the Construction of a Sociological Category

Only in this century has the social science of religion initiated a debate on the conceptualization of those without religious affiliation, who have historically been neglected as objects of study because of their statistical irrelevance. The concentration of research on Catholicism first and on the irruption of Evangelicals in Latin America and of Muslims in Europe later on explains the lack of systematic studies on this segment of society.

However, in recent years, the discussion on its categorization has become more relevant, which is in line with its growth in quantitative surveys in various countries. In the specialized bibliography in the United States and England, various terminologies are used as a way of cataloguing those without religion: “non-religion”, “irreligion”, “a-religion”, “no religion”, “religious nones”, “unaffiliated”, “nonaffiliated”, “disaffiliated” (

Speed et al. 2018;

Thiessen and Wilkins-Laflamme 2017;

Woodhead 2016;

Lee 2012). As the authors themselves warn, the use of the concepts is often imprecise and undefined. The tendency to unify them under an atheistic cosmology just because of the inexistence of some religious affiliation supposes a reductionism that blocks rather than clears research paths.

Undoubtedly, the heterogeneity in the biographies and in the ways of experiencing non-identification with a religious institution reflects the difficulty of synthesizing into a single category a social fraction that, for example, is already the majority of the population of the United Kingdom

3.

The attempt to classify them must not lose sight of the singularities. There are those who have a family background where religion was present and others who were socialized in an atmosphere devoid of religious identifications. In both cases, the present finds them assimilated into non-religious affiliation. However, the discordant trajectories and family environments can illustrate a diverse range of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors linked to the confessional dimension.

Atheists and agnostics are easier to recognize and classify, but they are not the ones who have given numerical density to those “without religion”. The increase is seen in the population that does believe in God but claims to have no religious affiliation when asked about it. It is this social conglomerate that challenges the sociologists of religion in their attempt to conceptualize and categorize. As we said, we are facing a population group with varied religious beliefs and dissimilar practices around the sacred. It is made up of subjects who are mainly believers but who do not have an institutionalized religious affiliation. In that sense, it is relevant to compare whether there are marked differences between their levels of religious beliefs, practices, and attitudes with respect to those who perceive themselves as having a confessional identity. At the same time, it is interesting to inquire about possible transits through spaces of spirituality, adhesions, and even practices linked to the religious of those who, for reasons unknown, make no reference to any particular religious structure.

Perhaps a common denominator on the way to building a category that synthesizes them is their detachment and estrangement from some institutional framework. However, defining them simply as “without religion” not only disregards the religious cosmologies that imbue them but also assumes that religious institutions hold a monopoly on the production and distribution of religious goods (

Bourdieu 1971). In contexts of multiple and widespread deregulations and manifest diversities, this starting point is not plausible as an interpretative framework. Groups, communities, and subjects live together and compete with the confessional institutions on this level.

Nor does the idea of disaffiliation fully resolve the challenge of categorization. While it may reflect the trajectory of those who were socialized and identified with a religion in the past and have distanced themselves from such a framing, not all those who do not identify with any religion went through the affiliation–disaffiliation sequence. This binomial conveys a rigidity that has no heuristic capacity to reflect the circulations, shifts, and intermittencies of individuals in their relationship with the sacred. In addition, a portion of this population does not recognize a religious frame of reference in their past, so it is not possible to disaffiliate from a structure to which they never ascribed.

Defining a concept that demarcates and identifies a universe of varied phenomena seems to be a difficult challenge. Given that we are in a field of investigation that is still under construction, we are provisionally inclined here to use a minimalist term but one that encompasses and describes the self-identification of this segment of society in religious terms. We will call them religiously unaffiliated.

3. Characteristics of the Religiously Unaffiliated

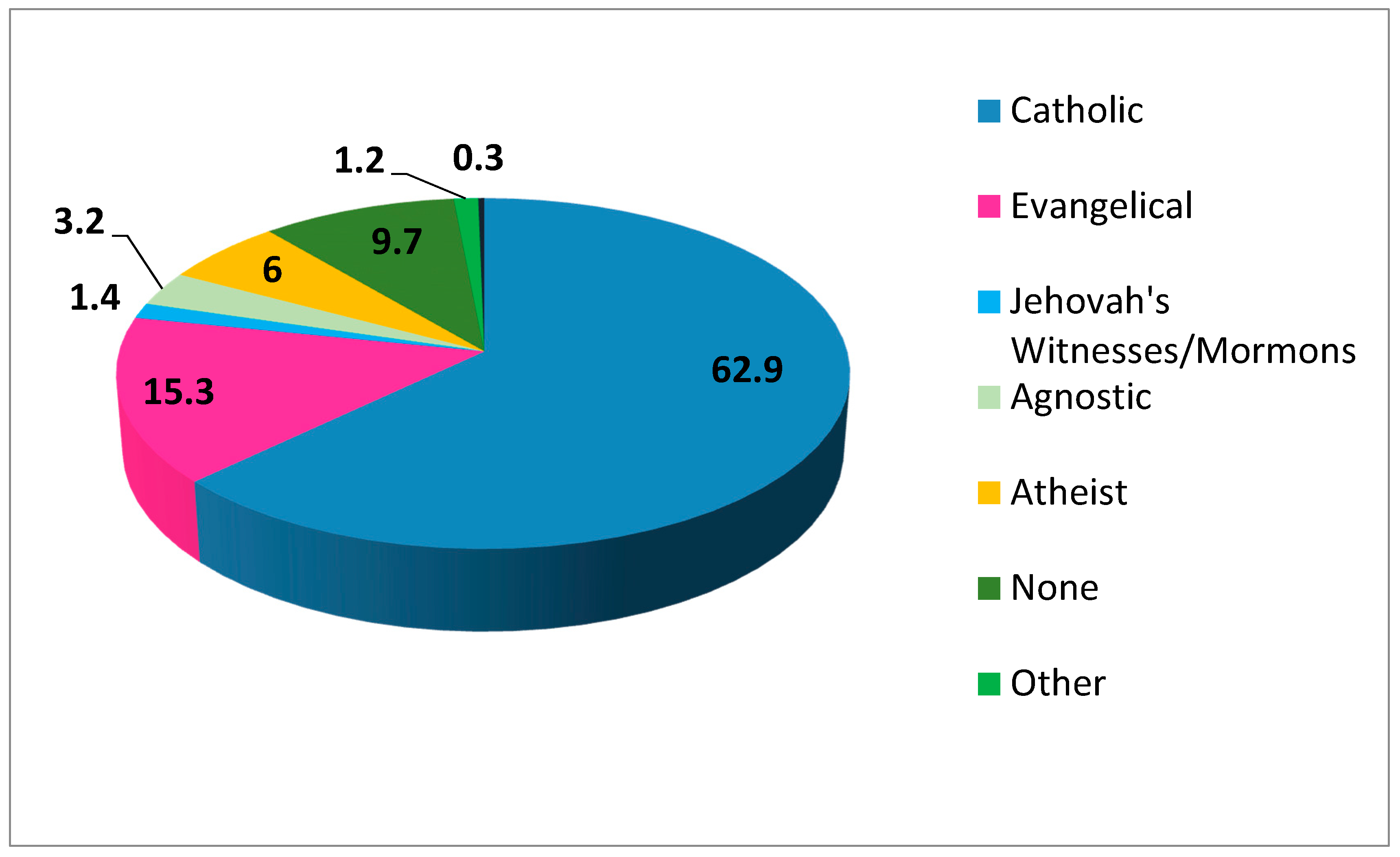

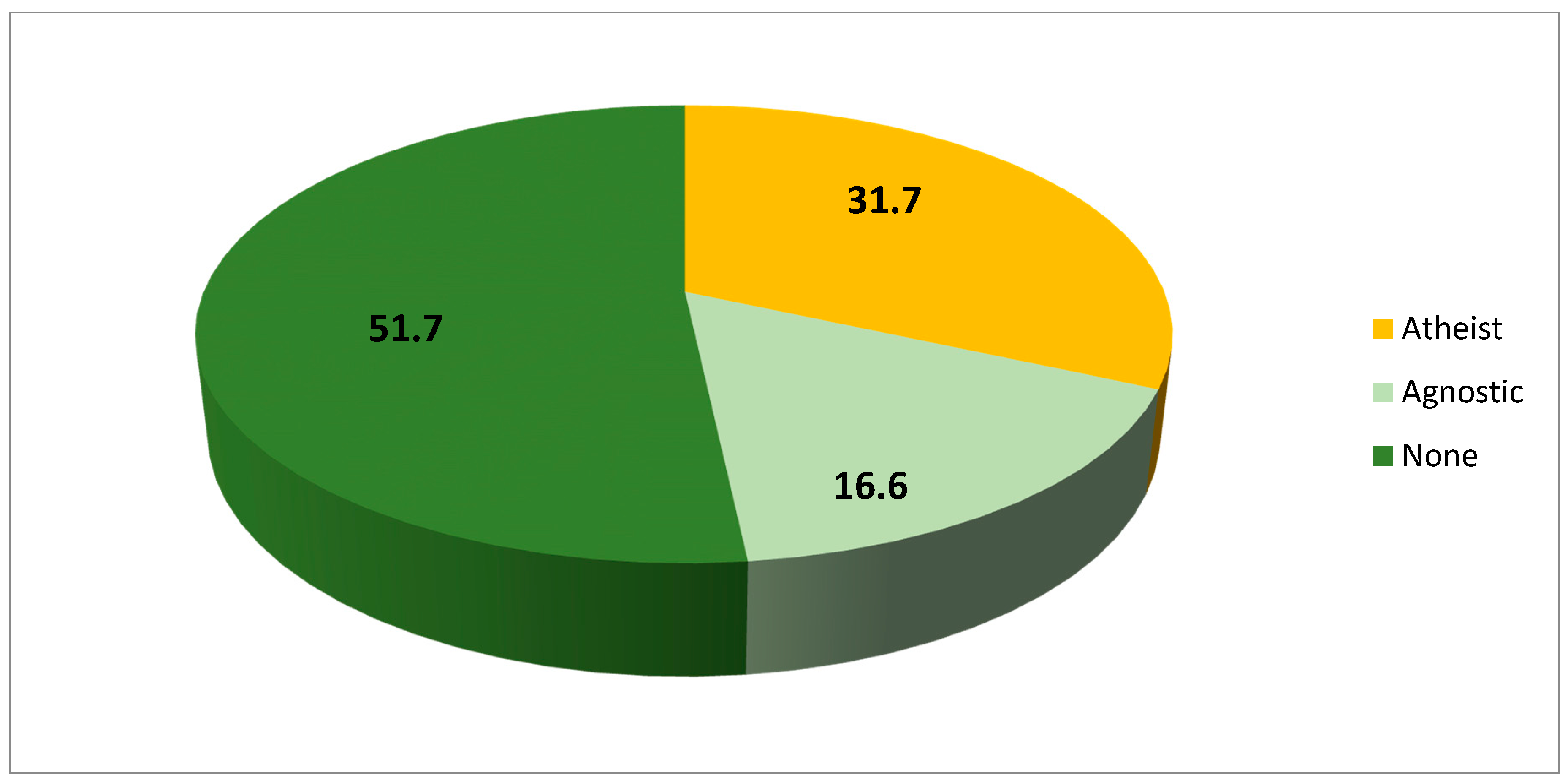

We highlighted in the introduction that 18.9% of the population of Argentina declared themselves without religious affiliation in the 2019 survey

4. This figure should be broken down into agnostics (3.2%), atheists (6%), and those who directly mentioned that they did not identify with any religion (9.7%) (see

Figure 1). If we take those religiously unaffiliated as a whole, 16.7% are agnostics, 31.7% are atheists, and 51.6% are made up of those who answered that they have no religion (see

Figure 2).

However, it could be thought that we are facing a homogeneous segment that shares the same universe of beliefs. Although the absence of any institutionalized framework emerges as a common denominator, we will now note a relative diversity in terms of their educational, age, and gender profiles and in regard to their perceptions, practices, and attitudes toward issues on the public agenda.

The unaffiliated are concentrated in the educational range with the highest formal education, representing 27.2% among university students and only 7% among the uneducated population. Within this segment, agnostics are concentrated in the highest educational levels: they reach 29.6% among university students. Atheists are more likely to be found among those with primary and secondary education, and those who claim to have no religion are distributed in a zig-zagging way without a defined pattern throughout the educational path.

Although among atheists men are more prevalent than women (33.7% against 28.7%) and the situation is the opposite among those who have no religion (50% against 53.9%), gender is not seen as a gravitating factor in the demarcation of profiles within this segment of Argentine society. As a whole, men declared that they had no religious affiliation to a greater extent than women (23.8% versus 14.5%).

It is mainly young people, and adults up to 44 years old, who identified themselves by the absence of a religious affiliation (24.7% and 23%, respectively), while people over 44 do so in a much lower percentage (7.7%). In the age factor, atheists stood out among the youngest (39.8%).

Belief in God is a relevant variable that allows us to deepen our understanding of the singularities within those religiously unaffiliated. A quick reading could draw attention to the fact that almost three out of ten believe in God. Most of these are those who claim not to have a religion and who, at the same time, do not define themselves as agnostics or atheists—believers without institutional religion. Less than half (48.3%) of them believe in God, surpassing even the segment that does not believe in him (46.1%). In the case of atheists, 92.6% claim not to believe in God. Although, as expected, among agnostics, those who do not believe in God prevail over those who do (48.7% vs. 16.7%), and those who have doubts about the existence of God stand out (27.4%) (see

Figure 3). Although we are facing low percentages, belief in God is not null among agnostics and atheists. A long-standing Christian culture in Argentine society still permeates even over those who are distanced from any religious perspective.

A first element of differentiation can be noted here. A considerable number of those who do not ascribe to any religion consider themselves believers in God, which is in marked contrast to atheists and agnostics. They identify their beliefs as being independent of institutionalized formats. They have a grammar that appeals to sacred references, but in their day-to-day lives, they show a total lack of involvement with any institutional framework, religious or otherwise. We are faced with an individualized lifestyle with social imaginaries that have confessional components that do not necessarily translate into principles of conduct in daily life. It will be important to analyze the implications of this particular configuration in other beliefs and practices linked to religious cosmology or, in other words, to different ways of interpreting the origin, the meaning of death, and the proper functioning of the universe from any religious paradigm. It will be important as well to unravel whether we are facing a configuration of a self-religious

ethos based on existing universes of meaning but without attachments to any one in particular (

Camurça 2017).

The self-perception of the degree of religiosity confirms the diversity of profiles within the religiously unaffiliated. Most (72.8%) of the agnostics rated their religiousness with less than 4 points. In the case of atheists, this score is 93.8%. For those who claim to have no religion, 58.1% gave a failing grade to their level of religiousness, and 14.4% of that segment attributed a score of between 7 and 10 points to their religiousness.

When it comes to explaining the reasons why they do not currently belong to any religion, more than half (54.1%) say that “it doesn’t make any sense” (in the case of atheists, this reason is given by 73.2%). Nearly one-quarter (24.7%) say that they “believe, but do not trust the churches” and 5.1% say that they had “a bad experience with a religious institution or a religious person”.

If we go into the beliefs of the religiously unaffiliated, we will observe that they show certain types of belief, although the figures are lower than those of the rest of society. For example, 71.6% believe in energy, 55.2% in believe luck, 36.8% believe in UFOs, and 34% believe in life after death and astrology (see

Table 1). The fact that three out of 10 believe in Jesus Christ deserves to be deepened. What does this answer mean? Do they believe in Jesus Christ as a savior with a religious sense or as a historically recognized figure? The quantitative survey prevents us from analyzing the meanings of the responses provided by the respondents. For this reason, we must be cautious in the conclusions that we draw on the data collected. Qualitative studies with in-depth interviews on this population segment will allow us to delve into the meanings given to these beliefs. However, the data enable us to highlight that distancing from religion does not necessarily imply absence of belief. Human beings show various forms of belief in a range of figures or icons, closer to or further away from those provided by religions.

Within the segment, those who claimed to have no religion appear again as the most believers in the aspects most identified with the institutionalized religious vade mecum (Jesus Christ, the angels, the Holy Spirit, the Devil, the Virgin, hell, the saints). On the other hand, they are overcome by agnostics in their belief in energy, UFOs, astrology, and healers. Atheists are the most incredulous in all ranges. It is noteworthy that 80.3% of agnostics believe in energy, and 42% of those without religion believe in Jesus Christ.

More than half (59.8%) of the religiously unaffiliated say that they have gone through situations of change in terms of religious affiliation during their lives. Most (85.9%) of that group identified themselves at some point with Catholicism, and 9.4% defined themselves as evangelicals in the past. According to these figures, we are in a position to affirm that the process of religious disaffiliation reaches practically 60% of this segment (without significant nuances within it), which represents 11% of the Argentine society in general. In turn, a relevant 39.7% of those without religious affiliation are characterized by an estrangement from the institutionalized religious spaces since their early age. These are diverse trajectories that show the heterogeneous nature of the universe of study (see

Figure 4).

Most (88.5%) of the respondents are baptized or have undergone a ceremony of initiation into some religion, and 45.4% have baptized or would baptize their children. In turn, almost all (96.9%) stated that their children should choose their own religion or belief. Baptism was represented as a naturalized rite more identified with tradition, transcending its original religious connotation. In fact, we had noticed that almost four out of 10 Argentines religiously unaffiliated claimed to have been socialized in a secularized family environment. Even so, the percentage of baptized people is considerably high. In any case, the fall to half of the actual or potential children baptisms reflects the magnitude of the process of distancing of this social segment from any institutionalized religious framework.

As for the religion of the parents, 69.6% of the mothers are or were Catholic, 9% were evangelical, and 12.4% were without religious affiliation; in the case of the fathers, the number of Catholics fell to 59.7% and that of evangelicals to 7.3%, while that of those without religious affiliation rose to 23.8%.

Several authors propose a correlation between family socialization and the projection of religious and non-religious identities (

Baker and Smith 2009;

Beit-Hallahmi 2015). It is worth asking then whether the family transmission of values and beliefs has the same consistency as decades ago. Do parents emphasize transferring their universes of meaning, or do they reinforce the idea of their children’s autonomy? In this sense, can we speak of a secularized family socialization (

Thiessen and Wilkins-Laflamme 2017)? From another perspective, it is noted that the erosion of the model of the nuclear family institution has smashed the processes of transmission of values (including religious ones) from one generation to another. It would not be the willingness of parents to freely choose their children that would lead to the emergence of new religious and non-religious affiliations, but rather the decline of intergenerational religious transfer (

Novaes 2004). In fact, among the religiously unaffiliated, only 9.7% of their families are not or were not religious and have or had a critical view of religion.

The relative blurring of the family as a frame of reference for religious transmission is not unrelated to the weakening of belonging and commitment to institutionalized religious spaces (

Pierucci 2003;

Mallimaci and Esquivel 2015). They are a constitutive part of a deep process of undermining the institutional fabric (in its state, political, educational, trade union, social and religious aspects), which is transversal to our society but which translates into conditions of greater autonomy or greater fragmentation, depending on the economic and cultural capital and the networks of social relationships of each person (

Bauman 2003;

Taylor 2007). Attendance at worship was traditionally the indicator for measuring the degree of religious participation. In contexts of attenuated institutionalism, it is essential to contemplate a range of practices not necessarily framed by confessional structures. Almost all the religiously unaffiliated do not attend worship. Some 70.8% never attend at all, and 28% only do so on special occasions. Together, they make up 98.8% of the segment. However, the infrequency of worship does not imply the non-existence of other practices linked to the sacred or related to spirituality. In activities of a more intimate nature, such as praying, 11.1% of the total of the religiously unaffiliated, and 18.2% of those who claim not to belong to any religion do so at least once a month. Meanwhile, 14% of agnostics talk to their deceased loved ones. Atheists, who are less active in these areas, play or gamble the most in betting games (“quiniela” or “bingo”): 13.2% do so at least once a month (see

Table 2).

Pope Francis does not arouse interest in the non-religious population of Argentina. Not only because he has not modified the levels of religiosity (85.9% expressed themselves in that sense), but also because 53.9% are indifferent to the maximum authority of the Catholic Church (in the case of atheists, it reaches 64.5%) (see

Figure 5). The agnostics are those who most value Francis as a “leader who denounces situations of injustice on earth”. Surely, in this appraisal, his social prominence takes precedence over his religious importance. On the other hand, one in four of those who say they have no religion consider that the Pope “is too involved in politics, instead of taking care of the spiritual part”.

The social segment religiously unaffiliated externalizes attitudes of clear autonomy regarding the doctrinal prescriptions of the confessional institutions. Eight out of ten are in favor of the priesthood for women, of priests being able to form a family, and see no contradiction between being a good religious and drinking alcoholic beverages.

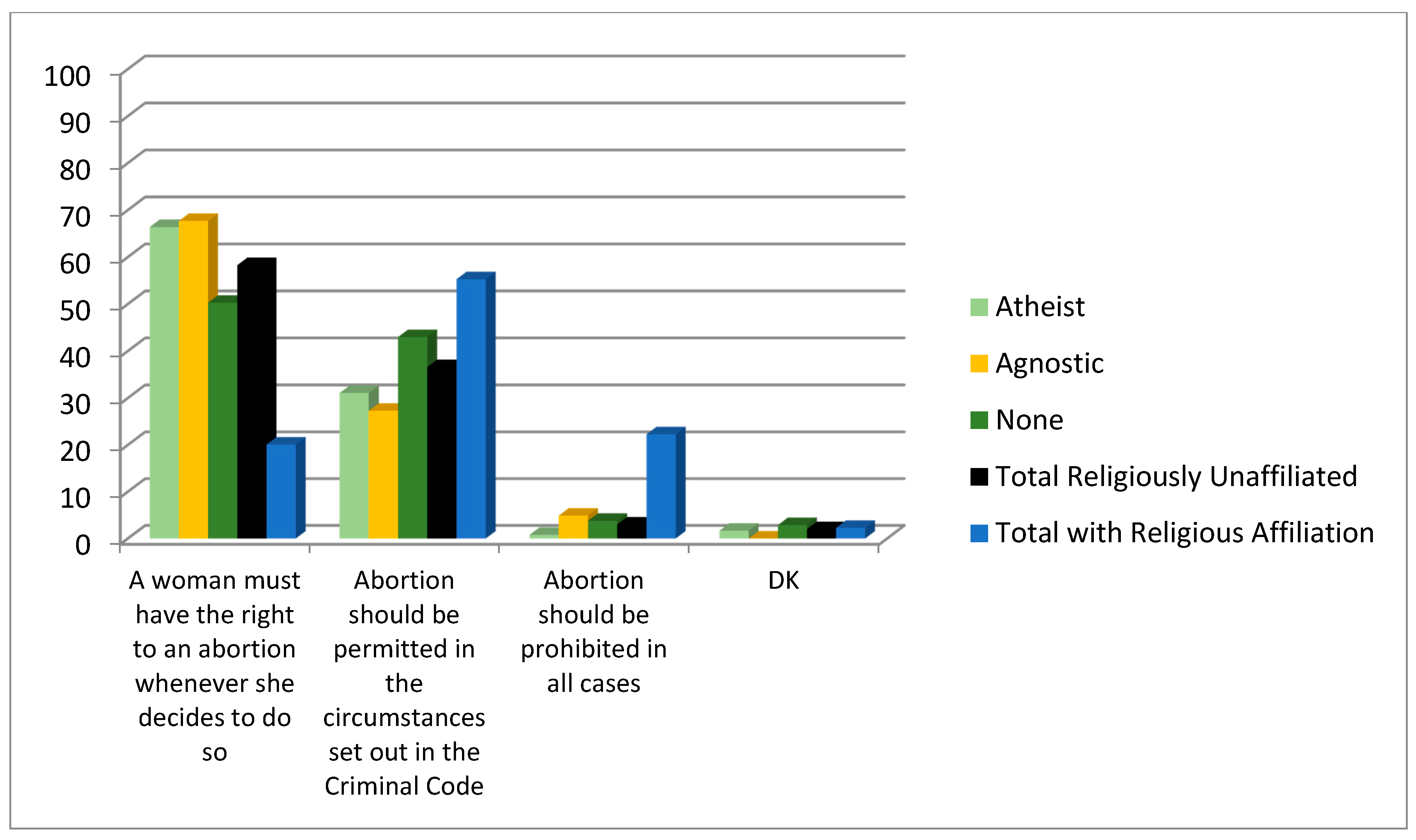

More than half (58.3%) declare that “a woman must have the right to an abortion whenever she decides to do so”; a little more than one-third approve of it in the circumstances provided for in the Criminal Code

6, while barely three out of 100 think that “abortion should be prohibited in all cases”. Atheists and agnostics stand out as the groups most likely to endorse unrestricted voluntary termination of pregnancy. Despite not having such a defined position in that sense, those who say they do not belong to any religion are clearly different from those who do have religious affiliation (see

Table 3).

As a whole, the religiously unaffiliated differ in their attitude toward this topic from the rest of Argentine society (total with religious affiliation). If, as we said, almost six out of 10 without religious affiliation consider that a woman should have the right to an abortion whenever she decides to do so, only two out of 10 of the rest of society agree with that position. At the other end, only 3% of those without religious affiliation argue that abortion should be prohibited in all cases. In contrast, 22.3% of those with religious affiliation are in favor of this position. At an intermediate point, for 36.6% of those without religious affiliation, abortion should be permitted in the circumstances set out in the Criminal Code. This is the majority option in the rest of Argentine society (55.3%) (see

Figure 6). In short, religious affiliation in general, and particular affiliation to one religion or another, are determining variables in the position that each citizen takes on the issue of abortion.

The survey also addressed the population’s disposition toward the end of life. Less than one-fifth (16.7%) of the religiously unaffiliated would let God’s will be done if they were terminally ill. For those who claimed to have no religion, this position rises to 26.4%. However, almost seven out of 10 of those without religious affiliation are inclined toward positions of autonomy of personal decision at the end of life, either because they would ask the doctors to end it (35.6%) or because they would ask them to do everything possible to prolong it (33.5%) (see

Figure 7).

Religious affiliation also emerges in this topic as an influential factor in the positioning of Argentine society regarding the end of life. Evangelicals appear to be more inclined to accept God’s will in a state of terminal health: 79.6% of them expressed themselves in this sense in contrast to 16.7% of the religiously unaffiliated (see

Table 4). Catholics, on the other hand, are somewhere in between. They would allow the divine will to be done to a greater extent than those without religious affiliation but in a smaller proportion than evangelicals.

Drug use is uniformly perceived by those without religious affiliation. Most (65%) consider it to be an individual decision, 17% credit it to a moral weakness or vice, while 12.5% consider it to be a disease. Nuances appear when consulting on what public policy should be regarding drug use. While only 2.6% of agnostics say that “drugs should always be prohibited”, among those who do not belong to any religion, this conviction reaches 15.4% (see

Figure 8). Most agnostics are inclined to believe that marijuana consumption should be legalized in all cases or at least for medical use. Atheists are the most likely to legalize all drugs.

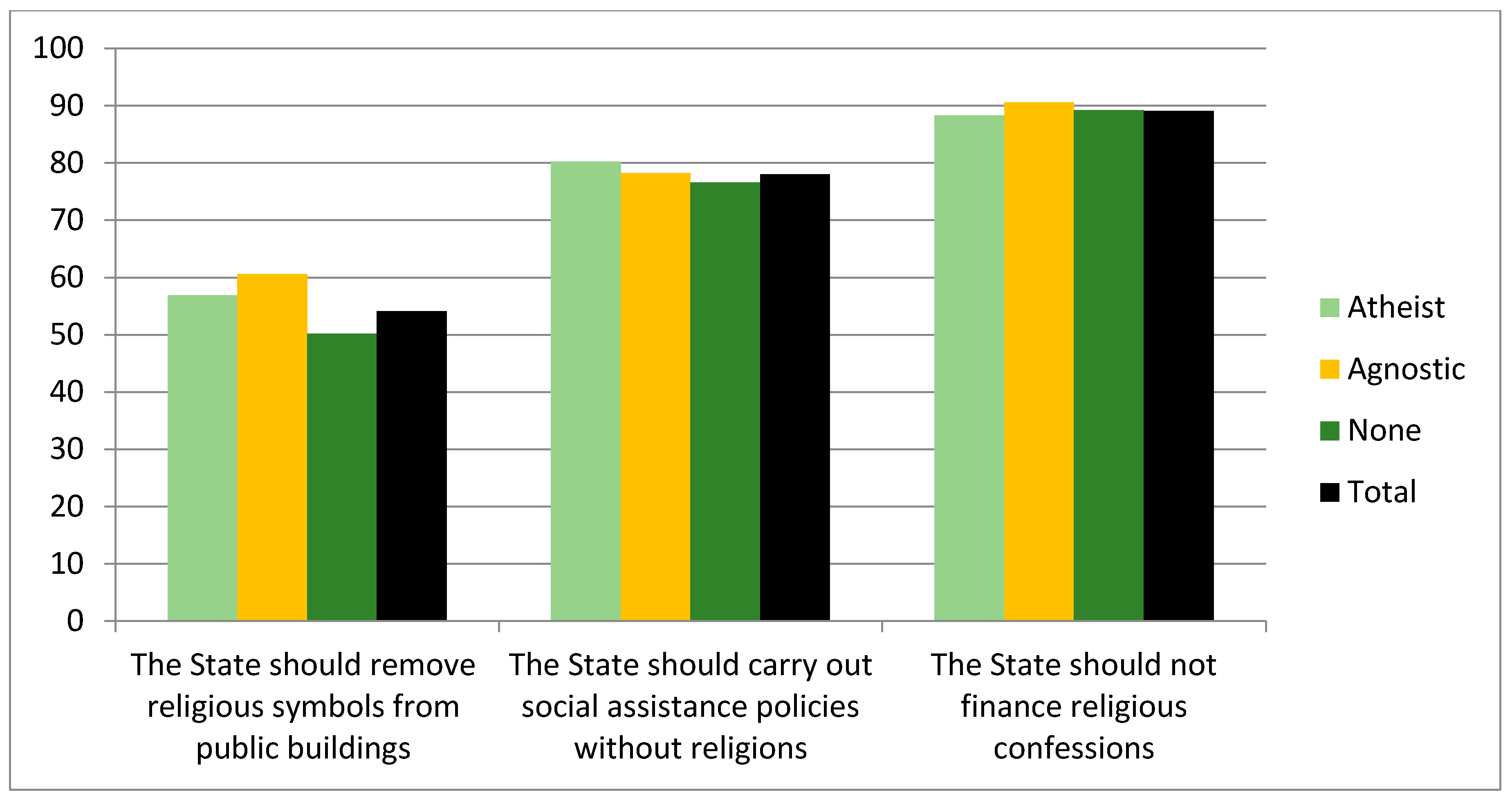

A strong position approving the state secularism is expressed on a range of issues concerning the relationship between the state and the churches (public funding of worship, religious education in public schools, religious symbols on public buildings, etc.). Nine out of ten of the religiously unaffiliated declare that the state should not finance religious confessions, 7.3% say that it should financially support all religions, and only 1.1% consider that only the Catholic Church should receive state contributions

7. This position basically relates to the payment of allowances to religious authorities.

Historically, religious institutions (mainly the Catholic Church) have participated in the implementation of social assistance policies in the territory. Not only have they channeled state programs through the Caritas organization, but they have also supported the incorporation into government staff of leaders socialized in a Catholic environment. Most (78%) of the religiously unaffiliated believe that public social assistance should be carried out without such participation. Some 15.4% support joint work with all religions in this area, while 1.7% are in favor of exclusive state collaboration with the Catholic Church.

Religious symbols in public buildings (ministries, hospitals, schools, etc.), although questioned, do not receive the same levels of disapproval: 54.1% approve of their removal and 21.6% are in favor of their conservation, while 19.4% are indifferent. It should be noted that religious symbols are part of the iconographic

vade mecum of public buildings, becoming cultural objects rather than elements of worship. Their presence is naturalized and, as such, often invisible (

Giumbelli 2012). In some sense, they are represented as part of the cultural heritage, anchored in tradition and put on a par with other patriotic symbols. As such, they have a status of universality, above particular religious beliefs.

As can be seen in

Figure 9, there are no noticeable differences in these topics within the religiously unaffiliated. Nuances are manifested in the intensity of the rejections: there is almost unanimous opposition to public funding of religious denominations, a majority questioning of the participation of religions in public policies of social assistance, and a nuanced objection to the presence of crucifixes and statues of virgins in state buildings.

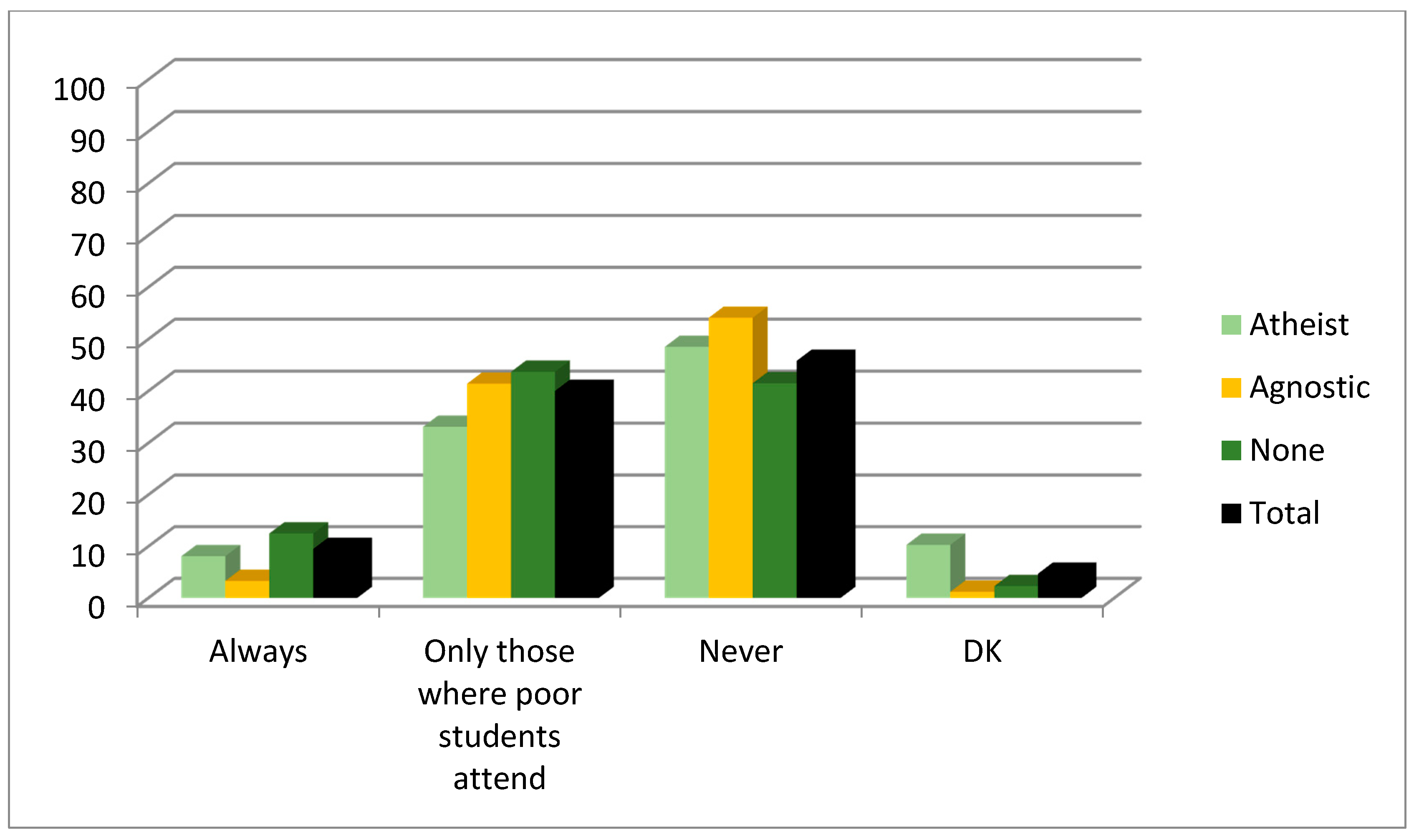

In the same vein, the majority of the religiously unaffiliated (66%) reject religious education in public schools. However, three out of 10 support the teaching of a general course on religions, and only 1.9% are in favor of the teaching of the Catholic religion in the public educational system. Atheists are the most refractory to confessional education in the public system, while agnostics are more likely to value the existence of a general subject course on religions (see

Figure 10).

Perceptions vary when it comes to evaluating public funding for religious schools. Rejection drops to 45.8%, since for 40%, this contribution is adequate in those establishments attended by deprived populations. For 9.5%, the state must always support confessional schools financially (see

Figure 11).

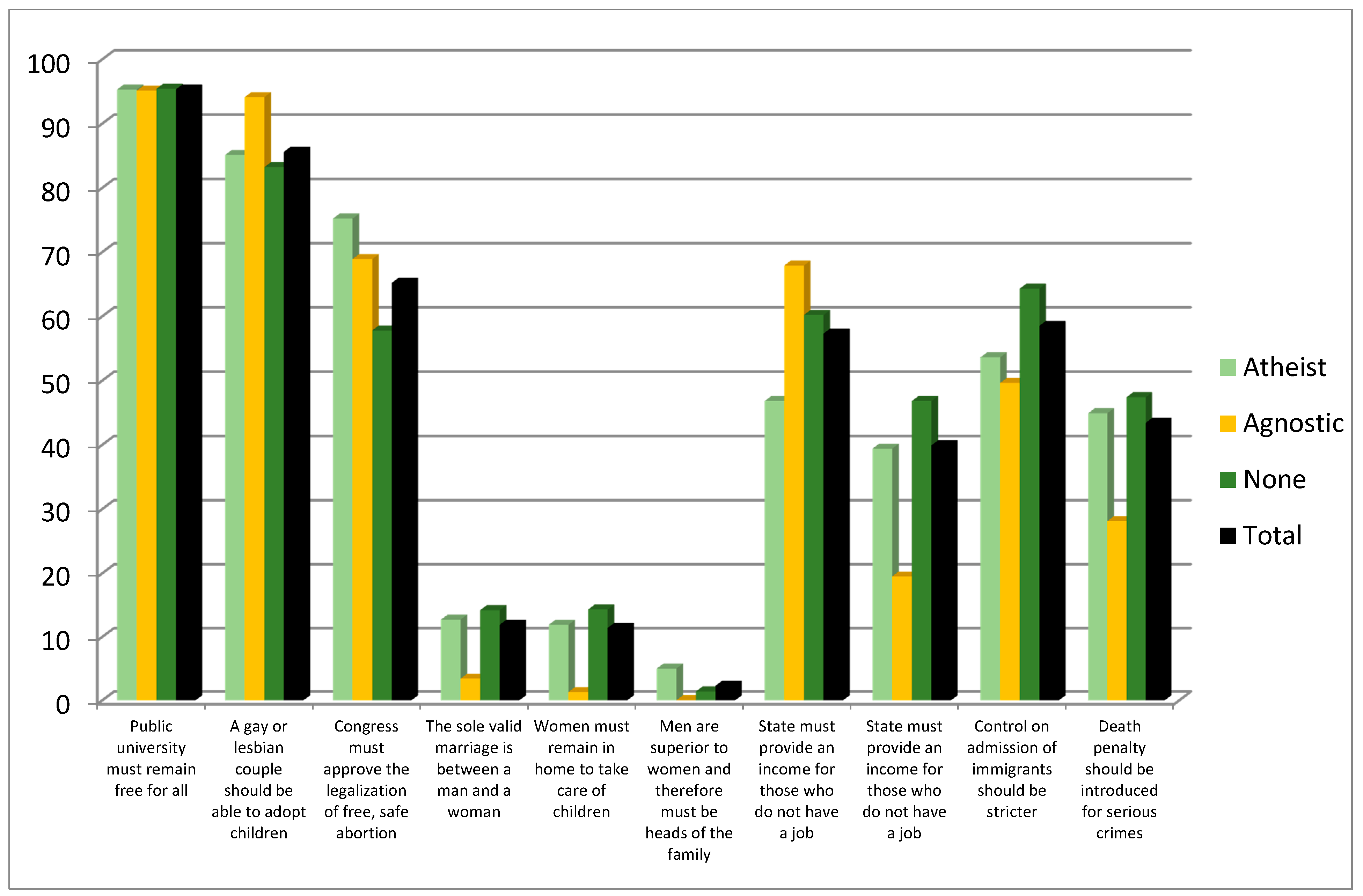

What about the ideological profile of the religiously unaffiliated? What do they think about public assistance to the poor, about the different family formats, about the relationship between men and women, about immigrants, about the death penalty? Are there different attitudes within this social segment?

The appraisal of the public and free university for all is practically unanimous. It represents 95.3% of all those without religious affiliation. The acceptance of sexual diversity and the possibility of same-sex couples adopting children also show very high levels of support (85.6%). In the case of agnostics, this compliance exceeds 94%. Two out of three are in favor of Congress passing an abortion legalization bill.

As for public contributions to the population without employment or in need of further support for their livelihood, the positions become somewhat controversial. More than half (57.3%) support a state provision of an income to those unemployed (approval rises to 67.9% in the case of agnostics), but for 39.9%, “public social assistance programs encourage laziness”. Again, the agnostics differ, with only 19.5% agreeing with this statement.

The recognition of rights to sexuality, family planning, and reproduction is not extended to other areas of social life. Almost six out of 10 people without religious affiliation maintain that control over immigrants should be stricter, and for 43.4%, the death penalty should be implemented for serious crimes (in the case of agnostics, the assent with the penal harshness falls to 28.1%).

Finally, 11.9% believe that the only valid marriage is between a man and a woman (only 3.9% for agnostics), 11.4% consider that a women should stay at home to take care of children (1.3% of agnostics expressed the same opinion), and 2.3% state that men are superior to women and should therefore be heads of households (see

Figure 12).

Beyond the evidence of a certain contrast in the assessment of some topics over others, which forces us not to follow paths of interpretative linearity, if we compare them with the total population, the religiously unaffiliated express higher levels of appraisal toward diversity, equality in gender relations, and recognition of the need to prioritize attention to the most vulnerable population. In the same vein, the death penalty for those who commit serious crimes and greater control over immigrants, although also significant, finds a lower degree of acceptance compared to Argentine society as a whole.

Among the religiously unaffiliated, the agnostics stand out for showing a higher degree of compliance with sexual diversity and gender equity, and a lower level of validation of harsh policies against crime and greater control over the entry of immigrants. The construction of a scale of ideological conservatism, based on the 10 statements in

Table 5 and including both social and sexual dimensions, clearly reflects the less conservative profile of agnostics among those without religious affiliation (see

Table 6).

4. Concluding Remarks

The analysis of multiple variables on religious beliefs, practices, and attitudes has allowed the identification of the religiously unaffiliated as a segment with unique characteristics and defined contours. We are dealing with a group that although diverse shows contrasts compared to the population with religious affiliation.

By way of conclusion, it is relevant to outline the distinctive features of those without religious affiliation. In greater proportions, they are young men and adult men up to 44 years old, with the highest level of education, living in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires and in the Argentinean Patagonia. To the extent that it is the younger ones who most express non-identification with a religion, it could be hypothesized that the growth of the religiously unaffiliated will be exponentially increased in the near future.

Despite condensing levels of belief below those of the rest of Argentine society, it would be inaccurate to say that they do not convey religious beliefs. Almost three out of 10 (most of those who responded do not belong to any religion but neither defined themselves as agnostics or atheists) believe in God and in Jesus Christ. These are the believers without institutionalized religion. Given that they are the most numerous sub-group and with the highest growth rate within the religiously unaffiliated, it would be unwise to consider this fringe of the Argentine citizenry as a-religious. As a whole, those without religious affiliation believe fundamentally in energy, luck and, to a lesser extent, in UFOs and life after death.

Nor can we unify them under the category of disaffiliates. Although six out of 10 have a history identified with some religion (and in those cases, it is indeed possible to observe a process of religious disaffiliation), the remaining 40% show paths defined by the alienation from the institutionalized religious spaces since their earliest age.

The religiously unaffiliated appear to have a minimum threshold of religious practice. Almost all of them do not frequent worship, although they evidence some kind of private practice or practices linked to spirituality, such as praying, speaking with deceased loved ones, performing yoga, or transcendental meditation.

They are prone to defend the autonomy of their children to choose their religion or beliefs; however, many of them do not dismiss the possibility of baptizing them. It is a habit internalized more as part of culture and tradition than as a religious initiation ritual.

Distant from the institutionalized religious frameworks, those without religious affiliation express attitudes of clear autonomy from the doctrinaire prescriptions of the confessional institutions, both in terms of their position in favor of the priesthood for women and of the priests being able to form a family. Similarly, they manifest a scale of secular attitudes regarding the autonomy of subjects over their bodies and have a secular imprint in regard to the state and its relationship with religious entities. Thus, they are the segment that most endorses the right of women to interrupt pregnancy, gender equality, recognition of diverse sexual identities, the right to decide on the end of life, and the legalization of drug use. In line with this, they believe that the state should have primary responsibility for providing sex education in schools and that it should not allow the teaching of religion in public schools. If the state applied social policies without the participation of the churches, did not finance religious denominations, and removed crucifixes from government buildings, they would appreciate it.

In all those topics, the boundaries with the population self-identified with some religion are significantly drawn. Although the normative regulations of the confessional institutions have lost effectiveness even on their own parishioners, they continue to permeate the idiosyncrasies and imaginaries of a Christian social majority.

Finally, the broad acceptance of sexual and reproductive rights is not apparent at other levels of social life. Stricter control of immigrants and the death penalty for serious crimes have been strongly supported by the religiously unaffiliated.

It is also interesting to synthesize the nuances among this population, which lead to differentiated profiles. We had already mentioned that those who claimed not to adhere to any religion and—at the same time—do not visualize themselves as agnostics or atheists, express the highest levels of belief in God and in Jesus Christ—hence, the relevance of thinking of them as believers without institutional religion.

In matters of high religious sensitivity such as abortion or the decision on the end of life, the greatest disparities are found within this segment of Argentine society. Atheists and agnostics stand out as the groups most likely to endorse the voluntary termination of pregnancy without restrictions or to request the end of their lives if they suffer an irreversible illness. Although distant from the population with religious affiliation, the specific group of believers without religious affiliation is inclined to more intermediate positions, both on the issue of abortion, as in the legalization of marijuana only for medicinal uses. Even a considerable portion would let the will of God be done in the presence of a terminal illness.

The place of religious teaching arouses some discrepancies among this population group. Atheists are more opposed to the incorporation of religion in public schools. Agnostics are the ones who most contemplate the possibility of a general course on religions. Considering the scale of attitudes to society, family, and home, agnostics stand out as the group that denotes a greater appraisal of a gender-equalitarian model of society, respectful of sexual diversity, inclusive of immigrants, and less inclined to accept harsh measures against crime as a methodology for solving problems of urban insecurity.

5. Discussions in Perspective

The exponential growth of the religiously unaffiliated deserves a series of final reflections as a trigger for new discussions and research. Its spreading among the population has given it greater social visibility, which in turn has reinforced its naturalization and social acceptance as one of the validated and legitimized options. In the same direction, the Evangelical growth at the end of the last century has contributed to the break of the “social norm” of being Catholic. In other words, it has significantly reduced the social cost of dissidence that comes from identifying with a religious minority or, directly, not recognizing oneself in any religion. Overcoming this symbolic barrier is important for the multiplication of this choice. Religion, similar to other components of individual and social life, is increasingly a choice, and within this range of possibilities, non-religious affiliation is consolidating as an alternative to be considered.

At the same time, the cultural diversity of our contemporary life has made not identifying with any religion a possible option. Processes that develop the autonomy of individuals reinforce the instances of personal choice and there, a choice is made between believing and not believing, belonging and not belonging. Religious institutions compete with each other and with the willingness of individuals to decide on their beliefs and affiliations. Day after day, belonging “by default” becomes less plausible. Moving through religious and spiritual spaces, without rigid boundaries, with intermittent and simultaneous stays and distancing with different temporalities, is the manifest expression of the process of individuation and subjectivation in the construction of the religiosity of each subject. Such an erosion of identity enables a person to think of himself without religious affiliation, regardless of the continuity of a variety of beliefs and practices linked to the sacred and the transcendent. In short, for some, non-religious affiliation is not necessarily a consequence of a loss of religiosity but rather of the weakening of the individuals bonds of belonging to institutionalized frames of reference. The emerging scenario of institutional ‘deregulation’ favors both the proliferation of diverse religious options and the spread of “

a religiosity that is freed from bonds and loyalties” (

Luiz 2013, p. 80). For others, non-religious affiliation is an active way of reaffirming their autonomies, and they engage in groups and organizations with the aim of propagating their views of the world (

Smith 2017;

Coley 2021). We can also find here another indicator of the cultural diversity of our contemporary life.

Regina

Novaes (

2004) and Marcelo

Camurça (

2017) question the temporary or permanent status of those who do not identify with religions. The spirit of the times is marked by a strong secularising pattern that runs through all levels of social life. However, in the religious field in particular, it manifests itself in a reconfiguration of religious representations and in the lesser plausibility of religious systems to regulate social behavior (

Hervieu-Léger 2008). This leads us to think that we are facing

being rather than

belonging. Instead of being a temporary situation of those who abandoned a religion and find themselves in search of another confessional attachment, it seems to summarize a new way of being religious without formal religion. It should be noted that the detachment from confessional institutions expressed in the option of non-religious affiliation is not limited to the realm of the sacred. In different areas of social life, there are few or no bonds of belonging to organized spaces.

In the introduction, we wondered about the family environment in which the religiously unaffiliated have been socialized and their trajectories in terms of religiosity. We asked if we are we facing processes of active disaffiliation or rather of religious indifference resulting from a family socialization detached from any religious attachment. We also raised the question about the similarities and differences between those who maintain their condition as believers even if they do not channel it through institutionalized frameworks and those who identify themselves with a religion but in a nominal way, without a daily religious insertion and practice.

Qualitative studies will allow a deeper understanding of the analytical dimensions that encompass the population without religious affiliation. It will be useful to analyze whether there are differences between those who expressed belonging to a religion in the past and those who were socialized in an environment without institutionalized religious references. Is it a question of representation, or of identity, or of inadequacy in relation to institutionalized religions?

Future research is likely to give greater substance to the concept of the religiously unaffiliated. For the time being, its heuristic potential has allowed us to describe subjects, beliefs, and practices that show a lack of affiliation with any institutionalized religious framework and mediation. From atheists and agnostics to disaffiliated believers and those who were never affiliated, it is possible to conceptualize this range of phenomena within this category, without ignoring the heterogeneity in the trajectories, beliefs, and religious and non-religious experiences that coexist within it.