2. Genesis of the Poem

So, how did this come about? It began here, on the banks of the Vézère. We were here because a friend had offered her house by the Dordogne to us for the summer to write. I had jumped at the chance, knowing that nearby, in the valley of the Vézère, was the Paleolithic site of Lascaux, whose famous story I first heard in my childhood: how a small group of adolescents, searching for their dog who had disappeared down a hole, found themselves in a complex of caves whose walls were covered with vast friezes of reindeer, horses, bison and aurochs (

Leroi-Gourhan 1984, p. 182, in

L’Art des Cavernes). I had long dreamed of seeing it for it had been one of the greatest discoveries of undisturbed Old Stone Age painting in the world.

That was all I knew when we arrived. On this particular day, we were not near Lascaux. We had gone out just to ‘discover’ the region a little, so we explored up the river as far as Le Bugue. It had been an idyllic day. We cleared up our meal and got in the car to go home. As we drove out of town, we saw a signpost, saying ‘Grotte de Bara-Bahau’: on the spur of the moment, we decided to go in.

An elderly lady with a pointer torch greeted us. Inside, there were none of the dramatic paintings I had hoped to see: the natural limestone formations were, however, intriguing, the atmosphere singular. Our guide explained the contours of the cave and rockface. Gradually, the damp coolness, the shadows, the confined space began to heighten our awareness. The guide used her pointer to highlight deep scars on the cave walls which we would otherwise not have noticed: they were the marks of Ice Age bears sharpening their claws as they awoke from hibernation. Then suddenly what we had in front of us were marks made by something else. The tiny spotlight traced other lines and out of the rock face emerged the engraved silhouette of a bear, stubby-maned horses, an aurochs, an ibex (

Aujoulat and Dauriac 1984, pp. 94–95, in L’Art

des Cavernes). They were moving, leaping, flaring the air. The wall was alive with their spirits, as the guide showed us how the natural accidents of the rockface had conjured up a spirit landscape to the hunter gatherers of the Magdalenian (ibid, p. 95); how this had spurred them to speak to the life in their underworld surroundings; and how it spoke back. A whole world of which I knew nothing rose before me; by the time I emerged out of this strange territory into the sunlight again, I was already a different person because I had encountered a new reality face to face. Who were the people of the Paleolithic? What was the world they lived in? And what were they hearing and seeing in the caves, and trying to tell us? An immense journey had begun.

Two summers later we returned. In the meantime, I had had another long poem sequence to finish, which was in fact a good thing. Poets formulate ideas, as do others, usually only slowly. Thoughts coalesce gradually around an initial idea, intuition, image or set of words that persists and will not go away. In my case, it frequently also involves lengthy and intensive research in very diverse areas, as I have written sequences on the Napoleonic War (

Davies 2005, pp. 33–52); the history of the Rhineland (

Davies 2016, pp. 69–91); the district of Southwark in London (

Davies 2005, pp. 55–64), the liturgical Hours (

Davies 2016, pp. 95–108) and the medieval theologians, Abelard and Héloïse (yes, you read that last appellation correctly) (

Davies 1997, pp. 50–73). The notion of a blinding flash of inspiration, followed by a perfectly formed poem written on the spot, is very far removed from the truth, though it can happen. So, during that time, the engravings of Bara-Bahau kept haunting me, sinking into the bedrock of my imagination, which is where all inspiration has to spring from if it is not to build its house on sand.

3. Conception, Research and Methods

So when we went back to Périgord, I knew that much work was to be done. One precious element, the first, of a value that is truly inestimable as I look back on it because it enabled all the rest, was the AA Big Road Atlas to France, 1992. I have it before me as I write. Its cover is virtually gone, the pages are frayed with much use, it has been stuck back together with brown packing tape (stronger than sellotape). It belongs to a pre-satnav era and I am truly astonished at the intricacy of the topographical detail. River valleys, inclines, forests, the imprint of long-vanished glaciers and volcanoes, as well as the later apparatus of modern travel and living, cities, towns, villages, hamlets, canals, railways, arterial roads and country lanes, all are visible. You really can read in anticipation the nature of the terrain you intend to cover, even in the car. My 2020 road atlas—yes, I still use maps as well as a satnav, as any self-respecting driver should—is impoverished by comparison, concentrating on roads and eliding much of the dimensionality of the land they pass over. As for the satnav, the less said the better.

This 1992 atlas has thus become, even within the twinkling of thirty years, a metaphor for how knowledge, and then, more catastrophically, perception itself, get lost. What was intimate becomes forgotten, what was all-encompassing becomes invisible. To understand how much this matters, I have only to turn to pages 101 and 102 of this book, which carry more marks, this time made by me. Along the watercourses of the Dordogne, Lot, Vézère and their tributaries I have ringed dozens of tiny place names; along the Aveyron and Ardèche far to the south-east there are dozens more. Sixty-five in all, and some of these represent complexes, rather than single spots. They are the sites of known Paleolithic habitats, cave engravings and cave paintings. The spectacular discovery of Chauvet cave in the Ardèche in Christmas 1994, the paintings of which date from between 37,000–33,500 and 31,000–28,000 BP (

Quiles et al. 2016) and the breathtaking uranium-series dating in 2016 on the constructed circles in Bruniquel cave in the Aveyron, placing them at c. 176,000 years BP, (

Jaubert et al. 2016) indicate how much more may still lie there, unperceived.

These marks show how I had started to map for myself, by making my own marks, what was there. I had materials to help me, scholarly archaeological and anthropological volumes, more and more of them as the years went on; without them the research necessary for the poem would have been impossible. Remember that this was in the era before the Internet. But first I found I had physically to ring the place names for a sense of what was really going on: the act of drawing on the map turned it into a negative palimpsest for, as I did so, the ‘shape’ of another, lost culture, started to emerge. Just as it had in Bara-Bahau. What it showed was a geographical preference for steep river valleys, which then attracted a density of population, which had in its turn produced a concentration of social and spiritual energies. In short, nature, the human world and faith were inextricably linked.

We set off up the rivers in search of these landscapes. The Périgord of the late 20th century was, as I have said, bewitching. But very quickly I realized that something was not right. What I was seeing could not possibly have prompted what I met in the decorated caves. It was not merely a case of agriculture having taken over from forest, of humankind moving in with domestication. For we had clearly been here long, long before all that, and for a very long time: the oldest friezes or engravings I saw dated from about 25,000 BP (

Roussot 1984, p. 156, in

L’Art des Cavernes), the youngest as little as 13,000 BP (ibid. p. 163). Nor was I satisfied by the standard narrative that the aurochs, the mammoths, the cave bears, the Przewalski horses, the reindeer depicted had simply died out, or were not there any more. That was obvious. Why were not they there? Why were not people still entering the caves to encounter the cave of their own minds and the cave of God?

Les Eyzies de Tayac lies at the centre of this conundrum. This large village of less than 1000 inhabitants sits in a bowl of steep limestone bluffs where the Vézère meets the Beune. It is at a natural crossroads through the high plateau above. It was here in 1868 that the paleontologist Edouard Lartet excavated an ancient Homo sapiens skeleton under an overhang and gave the alternative name of Cro-Magnon to us, modern humans

1. But my map showed that the area had sites of Paleolithic activity under or inside virtually every cliff, the names so famous that they make every archaeologist of the Old Stone Age go weak at the knees: Font de Gaume, Bernifal, Laugerie Basse and Laugerie Haute, l’abri Pataud, La Micoque … all this explains why this unassuming town is a UNESCO World heritage site

2. For millennia, during a crucial period of our history, it was a focus for exchange of all kinds, material, social and spiritual, for the elaboration of systems of belief and the creation of a sacred temenos.

So powerful was the after-image of this fact that I wished to try and bring back into being, in poetic form, this vanished and frequently misrepresented world. I sensed it contained wisdoms that we once knew but which we have forgotten. This was the genesis of my sequence, ‘When the Animals Came’, published in the collection,

In A Valley of this Restless Mind (

Davies 1997).

I understood already in Bara-Bahau that the key to unlocking the first door of understanding lay in the world that surrounded paleolithic man. To evoke how the cave painters lived, created, worshipped and died, I needed to re-imagine for myself the horizons that shaped their imagination. I needed to

live in it again. This required two quite different approaches to my research. Firstly, it meant actually visiting all the sites open to the public in the region, and some that were not. To do this, of course, I had to find out where they were. This is not straightforward since only the most famous are listed in normal tourist guidebooks. So, I started acquiring scientific volumes by the archaeologists who had worked on numerous smaller sites to give me a properly three-dimensional sense of this culture, or civilization, as I rapidly began to think of it. I persuaded young research students, who are often used as custodians on the ground in the summer, to show me at least the entrance to sites normally only open to professionals. One agreed to chaperone me round the countryside to find the most secret: one of the headiest moments was standing outside La Ferrassie, where at least seven Neanderthals were ritually buried c. 50,000 BP (

Johanson and Edgar 1996, p. 226).

Many of the sites are not in caves but under cliff overhangs, known as ‘abris’: these offer the richest assortment of the day-to-day life of the Paleolithic: implements, domestic and for hunting, evidence of hearths, assemblages of plant and animal matter that give insight both into diet and the paleo-ecology of the area, sometimes human bones and burials (

Mellars 1994, pp. 61–64, in

Cunliffe). The headline-making painted and engraved caves, the habitat of the interior and spiritual world, were, by contrast, for encountering the numinous, not the everyday. These are places both of sensory deprivation and heightened sensory perception, a paradox more apparent than real: without torchlight—of course Paleolithic society had lamps fuelled with animal fat (

de Saint-Blanquat 1987, p. 198)—you enter a darkness never experienced above ground, even on the blackest night: it is a uniform, velvety darkness, without dimension. This means that very quickly you lose a sense of your own dimensions too, which is disorientating in the extreme. If you then light up the space, the walls suddenly come alive, move, show you their forms, and your enhanced perceptual awareness instinctively breathes life into them. This would have been even more the case with flame, which is dynamic, always becoming and leaving. Add to this the experience of sound—some guides will do this, the sound of a human cry—it enlarges, echoing and booming and returning in distorted form in palpable waves out of the earth’s most intimate chambers, a living, terrifying thing. This is the moment when you do indeed begin to encounter the godhead, and it is the caves that give you that presence. It is one of the most unnerving experiences I have ever had.

I rapidly realized, however, that as well as a topographical understanding, I needed to know what the ancient environment was like. The fauna depicted in the caves is indicative of a cold climate at this southerly latitude, a deeper phase of the Ice Age that we are still in (just). What sort of a place was it? To recreate the ecology of the Old Stone Age entailed studying the detailed and copious scientific research conducted in the last fifty years in a gamut of disciplines: paleobotany and paleozoology, geology, climatology, physics, chemical and biological isotope analysis, carbon, thermo-luminescent and uranium dating. Only then can the imagination be allowed to do its work; otherwise, the whole exercise becomes mere psychological projection, and there has been a great deal of that in regard to the Paleolithic, I discovered. We are all familiar with the grotesque popular image of prehistoric man as a half-starved, half-naked, runty individual spearing the odd fish before clubbing his unfortunate womenfolk round the head as a prelude to love-making; sadly, some of these caricatures can be laid at the door of less rigorous archaeological theories from the past (

Gamble 1994, p. 8, in

Cunliffe). I wanted imaginatively to uncover a different reality.

So, in my mind’s eye, the maize and tobacco fields, the dense oak and sweet chestnut forests by which we were surrounded and which in the past had hidden the sites, even protected them from depredation, all had to be stripped away. I looked out upon a landscape where, c. 20,000 BP there were few trees, except in the valleys, where taiga and grassland steppe spread across the plateaux as far as the eye could see (

de Saint-Blanquat 1987, pp. 143–48). Fast-flowing ice-melt- swollen rivers carried down vast quantities of gravel that split them into braided channels such as exist in northern Canada and Alaska today, full of fish (

de Saint-Blanquat 1987, p. 134). Plant life was various and rich in nutrition; the grassland supported migrating herds of reindeer, mammoth, bison and aurochs in untold numbers which, in their turn, supported populations of predators such as cave bears and lions (

Mellars 1994, pp. 61–64, in

Cunliffe). This was a landscape which offered natural resources in abundance to the sophisticated, resilient and skilled human beings for whom it was home.

Ethno-archaeology and experimental archaeology also came into play. At the site of La Micoque, I watched expert knappers free a tool from a nodule of flint and then prepare a hide; at La Chapelle aux Saints how you spark fire from dried mushrooms and crush paint pigment from minerals. At the Préhistoparc in Tursac, I stood on the safe side of a (very robust) fence to look at a backbred Taurus bull in order to gain an idea of what an aurochs might have looked like. (A small idea: its torso stretched away from me, seemingly the length of two domesticated cows head to tail.) Tepees dotted the site around as a reminder of the proficient nomadic life of the ancient inhabitants of south-west France. I tried to learn about the relationship that hunter gatherer societies had to the land and their natural environment before modern colonial incursions, and about the way modern pastoralists co-exist with their reindeer in Siberia and Lapland. Although one must be careful of identifying these societies with those of the Paleolithic, study of them certainly helped to understand the complexity, variety and quality of the finds in south-west France, and how inward this society was with the natural and divine worlds. Or, better expressed, how the natural and divine worlds were as one. For one constant they all have in common struck me: for them, the natural world is manifestly sacred. Long, long before man farmed or lived in cities, he was a spiritual being and an artist. It is the primacy of these intertwined aspects of our humanity that I wished to convey in my poem.

4. Commentary

I decided to set the sequence in and around Les Eyzies de Tayac because of the density of its sites. I condensed the time scale into the cycle of the four seasons, during which the evidence of many millennia of such cycles occurs. Intuitively, this seemed right for such a subject matter, for a society whose conceptions of time differed so radically from our own. By doing this, I wished precisely to call into question the physicist’s ‘entropic’ structure of time that we assume today, and remind the reader of a more organic model.

The first poem, ‘Autumn’ narrates a reindeer hunt along the Vézère: as the herd migrates, driven by the changing season, the hunters and their families must move with them, bound to them in the matrix of life and death. ‘Winter’ is a time for consolidating activities, such as tool-making. I imagine the women as just as involved in the expert making of tools as the men; this is also the section where we meet the two main protagonists, the shaman, Sinhikole, and his wife, Ezpela. The third section belongs to them; it is a celebration of their love and marriage, a union begun in youthful glory but refined over many years of experience together. In ‘Spring’, the major sequence in the poem, the tribes gather for exchange, feasting, and worship, to enter into marriages and share knowledge. The crux of the sequence, however, is Sinhikole’s descent into the caves to enter the spirit world, which I give and comment upon in detail below. Finally, in ‘Summer’ I evoke how this way of life came to an end, and the coming of the great forgetting.

In the excerpt below from ‘Spring’, I place the enactment of belief centrally. Sinhikole, the birdman, the one who acts as psychopomp for the rest of his people, opens up our sacramental relationship with creation. Since the first discoveries of the cave paintings in the mid 19th century, there has been constant speculation about the significance of what is depicted there for the artists who made them. They were initially interpreted by the Abbé Breuil, one of the first to propose a scientific dating method and analyse the sites, as ‘sympathetic magic’ to ensure a successful hunt (

Clottes and Lewis-Williams 1996, pp. 69–70) in the 1960s by the structuralist André Leroi-Gourhan and others who elaborated a system of correspondences between the animals and the male and female principles (ibid, pp. 72–75); and most recently, and in my view, most convincingly, by the archaeologists Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams as a means of communicating with the spirit world that infused every action of the community (ibid, pp. 102–3).

As the shaman, Sinhikole is invested with these powers of contact and interpretation. To carry out his task, he must enter the womb of nature, both in actuality and symbolically, to commune with the transcendent spirits who are on the other side of the wall. This is a realm of renewal, the reiteration of ancient promises and a reminder of custodianship. It is also the kingdom of fear, and violence, and annihilation. In thinking about this, I was of course struck by the fact that such ideas and tropes are universal in human belief systems, even through their expression may take different forms; I recognize in them my own Catholic beliefs, which, so far from contradicting or invalidating what I saw and imagined in the caves, or being invalidated by them, were enriched by this foretelling. In this I have an illustrious predecessor, the poet and painter, David Jones, who early understood the theological significance of such sites as Lascaux and Paviland in the Gower peninsula, site of the oldest known ritual burial in Britain and contemporaneous with many of the sites in Périgord c. 29,000 BP.

3 He linked the Catholic mass to the sacramental activities of the Stone Age in ‘Rite and Foretime’, the first section of his long poem The Anathemata, ‘But already he’s at it/the form-making proto-maker/busy at the fecund image of her./Chthonic? Why yes/but mother of us…. See how they run, the juxtaposed forms, brighting the vaults of Lascaux’ (

Jones 1955, pp. 60–61). We even meet the idea of Christ as the opening through the curtain into the sanctuary, ‘by the new and living way he opened for us through the curtain (that is, of his flesh)’ (Letter to the Hebrews 10:20, NRSV, 222).

As the darkness, the sensory deprivation work on Sinhikole and the other initiates, so this prepares them for the arrival of the spirit animals. These first give themselves to the human mind out of the shapes and accidents of the rockface, the natural world, and are then conjured up by the art of the worshippers, in other words, by their spiritual understanding. The process is reciprocal and metamorphic; the visions grow together and suggest new possibilities. This interpretation is borne out by the fact that some sites were revisited and re-worked over thousands of years. Another element suggestive of the ‘co-operation’ between the human and the divine are the multiple handprints found in conjunction with so many paintings, which Jean Clottes proposes were created when the initiates placed their hands on the wall ‘veil’; by then making the outline of the hand by blowing pigment round it, they crossed through into the spirit world (

Clottes and Lewis-Williams 1996, pp. 33, 95–96).

For the focal image, I drew upon the most mysterious painting of all in Lascaux. It is at the bottom of a dangerous fifteen-foot deep shaft called ‘the pit’, where a rare depiction of a human, apparently gored and dying, lies beside a gored and dying bison (

Aujoulat and Dauriac 1984, Plate IX, in

L’Art des Cavernes,). Its secret and inaccessible position, together with the artifacts found there: spears, resin, lamps, suggest a closely guarded sanctuary. It is legitimate, therefore, to accord this depiction prime importance in the spiritual beliefs of those who made it, especially as similar scenes have been found at several other nearby sites. The wounded man as mediator and messenger, a person with special spiritual knowledge, is one of the most widespread and enduring psychological and theological tropes in human culture because it acknowledges the brokenness of the created human state, and the need to heal it. The Christian tradition has its own all-encompassing account of this necessity. I had these connections in mind when writing the end of this section: as Sinhikole emerges back into the light from his communion with the spirit world, his wife comes to meet him with the news that his little daughter has died.

- ‘Omphalos is hard. Menacing. Dark.

- Make sure your torch is primed, the wick in your lamp

- And suet in it. Follow on your belly through the passageways

- And count every stage of deepening terror as a kind of grace.’

- Sinhikole, cold from years of teaching, exhortation,

- Squats mechanically at the chamber door

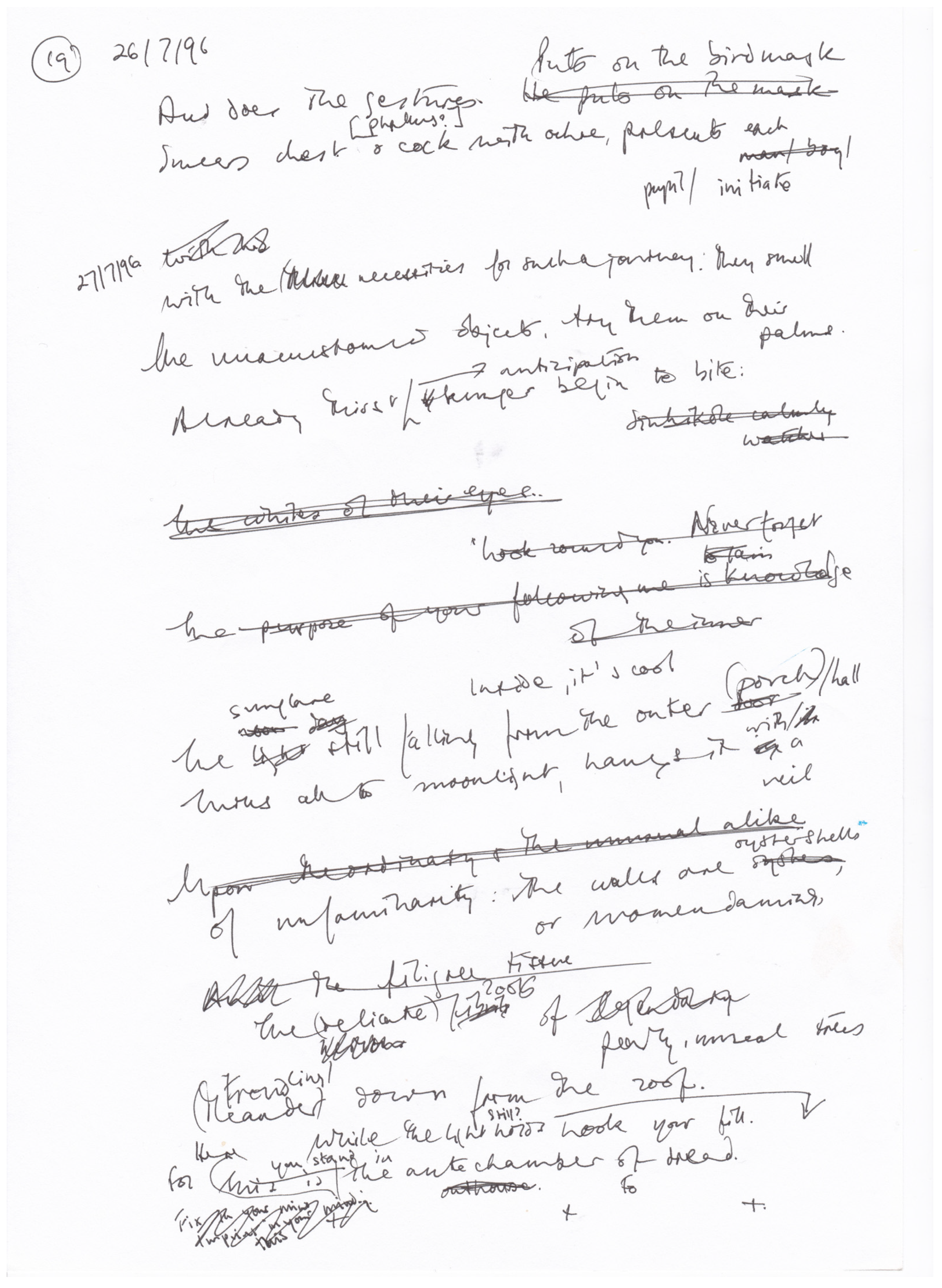

- And does the gestures. Puts on the birdmask,

- Smears chest and cock with ochre, presents each initiate

- With the necessities for such a journey; they smell

- The unaccustomed objects, try them on their palm.

- Already thirst, anticipation, hunger begin to bite.

-

- Inside, it’s cool, the sunglare still falling from the outer hall

- Turns all to moonlight, hangs it with a veil

- Of unfamiliarity: the walls are oyster shells

- Or women dancing; the roots of pearly, unnatural trees

- Frond down from the roof.

- Look your fill while the light still holds—

- This is the antechamber of dread.

- * *

- Cold, damp, like dead men’s hands running

- Along your back and shoulders, between your thighs,

- And then this sight—or rather, no-sight, what you’ve never seen,

- No night like this has ever blindfolded stars, put out the moon;

- Always we receive the phantom, shadow, to lend us body

- In the absence of our noonday selves.

- Not here.

- Here is no sense of up nor down, nor time nor season;

- No colour, no form with meaning, no warmth,

- No sound, no breath of air, but black invading every orifice,

- Black in your ears and eyes, black on your tongue,

- Black behind, above, beneath, black to annihilate thought,

- Black to drive out the world, black to usher in insanity.

- * *

- Lift your torch and run it along the gallery wall.

- This is what you have come, and now must learn, to see.

- Bereft of all the things you use to define yourself outside.

- Here you have nothing but what lies within your field of vision,

- Buried in the very viscera of earth.

- No-one knows when we first found a distance

- Between the felt reality of bark, or pebble, or muzzle

- And a reality within the mind—call it the inability

- Not to recall, to put out of our mind the presence

- Of what we cannot see. Don’t think a few visits here

- Will make of you an adept; remember always

- You will never know except by exploration and re-exploration

- What it is you seek. All those who have finally achieved

- Some wisdom in these caves know this means hardship, separation,

- Hours in the flickering gloom just keeping watch.

- Fix upon one feature: the sprung ears and head

- Of this red stallion, the way he leaps towards his mare,

- Or the moult line here upon the bison, the irritated gait of rut.

- Sit very still before these images

- And soon the enclosed space and visionary drink

- Work their effect. Do you feel how the cave imperceptibly,

- Relentlessly, fills with movement, and the clayey stink of tomb

- Is overlaid with musk and grassy breath?

- And somewhere from the uterus of time,

- From the passageways which lead off down from us,

- Rises the rumour of a bayed rhinoceros—

- Out of the shadows he starts, sniffing the air,

- Scenting us, as quick as a chamois sheering away on his toes

- And gone. Swimming in an alchemical river,

- The herds of stags sprout antler forests reaching up to heaven.

- Above them a one-ton aurochs gyrates gently in the air.

- Behind the calcite curtain, one hundred thousand lions

- Prepare with loping strides their sortie from the stone

- And jut their eager heads along the eaves.

- Their baby mammoth prey floats like thistledown on the breeze.

- Do you hear now the thrumming in your temples

- That is the attunement to these metamorphoses,

- The preparation for the most difficult place?

- …

- No monument but a frozen image

- Of dying man and disembowelled bull

- Who are the illumination of the other side of time.

- Here is the fierceness of the pointed moment,

- The moment when it is no longer possible to play

- Among an infinity of possibilities, or stay the change

- Of harpoon strike, horn-gore, the passing of what is seen

- And present into the unseen, the perpetual elsewhere.

- All bulls are contained here in the tilt of the head,

- Horripilated mane, the entrails hanging like a sex between the legs,

- And all men in the birdman, privileged of the tribe,

- Who must, in order to make bearable to us

- The horror of our journey out of time,

- Suffer the wound, suffer the exiling moment,

- Be powerful enough to take upon himself

- The burden of fear, of loss of strength, disgrace,

- Extinction, that we have come, in the pit of these dark caverns,

- To encounter and defy.

- For no-one who has not suffered wounding

- Hopes to heal.

- * *

- (Details see Appendix A)