1. Introduction: The Museum Movement

During the French Revolution, agents working under Napoleon’s aegis removed Roman Catholic implements and materials from ecclesiastical contexts. A number of these materials were installed in the Musée du Louvre, setting the precedent for appropriating religious materials within a new industry of “fine art”. The industry of the fine arts begun in the eighteenth century evolved into a universalized system and art market by the nineteenth century. Today, acknowledging ecclesiastical artifacts as fine art has become so ingrained that visitors to public art museums rarely stop to consider the disciplinary channels through which religious and ritual artifacts have been quietly yet purposely transformed into secular objets d’art.

Today, American fine arts museums possess countless examples of medieval Christian liturgical and devotional artifacts—from Old Masters biblical paintings to the ecclesiastical implements of Roman Catholic Church services, and personal items such as devotional altars once used at home. In the wake of the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation, a great number of Roman Catholic ecclesiastical implements as well as objects of personal devotion were either destroyed outright or refashioned for non-religious use. At the opposite end of this decimation of Catholic material culture were countless unknown rescuers who secreted devotional and liturgical materials into private hands, thereby preserving them. This rescuing was done in the optimistic hope that Roman Catholicism would once again dominate in Europe, or for less sanctimonious motives such as creating private collections of “curiosities” out of church treasures. Eventually, the Enlightenment and its proponents’ theories of Reason, Taste, Beauty, and Aesthetics led to the establishment of the modern system of art and its material expression in newly founded “art museums” (

Shiner 2001). As André Malraux notes in his meditations on art and art history, “Museums without Walls”, the idea of art as an epistemological category of knowing was required prior to viewing religious artifacts as something other than sacred materials used in ritual, contemplative, ceremonial, or devotional practices as they had been in previous generations (

Malraux 1953, pp. 13–130).

Though this description drastically oversimplifies these historical forces, categorizing Roman Catholic liturgical material culture—chalices, pyxes, ostensories, censers, reliquaries, basins, candlesticks, hanging lamps, processional and altar crosses—as

art was a direct result of the Enlightenment’s influence on the practices and activities of the French Revolution. These activities culminated in the establishment of the first public art museum, the Louvre in Paris, France. What the rise of Renaissance humanism did for Catholic-themed paintings, the French Revolution did for ecclesiastical and liturgical implements. Consequently, collectors, connoisseurs, and critics epistemologically reshaped the meaning of liturgical objects in the formation of art history as an academic discipline in the nineteenth century. Religion evolved into art, giving birth to new modalities of veneration such as connoisseurship and art criticism during what has become known as “the museum movement” (

Bazin 1967). Function was sublimated to form as aesthetic ideology, capturing the cultural imaginary of eighteenth-century elites across Europe and America and reshaping the ecclesiastical or devotional material culture’s central purpose as the focal point of religious contemplation into an aesthetic object of contemplation that focused on formal analysis (line, shape, space, texture, color, etc.).

This same aesthetic priority undergirds the educational mission of many contemporary fine arts museums, with their dedication to fostering in audiences an appreciation for art as a civilizing and inspiring celebration of human achievement. One does not need to look beyond the mission statements of any American art museum or the statements of early museum advocates to recognize the pervasive claim that the significance of art lies in its perceived pedagogical value (

Genoways and Andrei 2008). Everyone knows that art museums secularize liturgical objects and provide new educational information about them, but the dynamics through which this happens are more obscure. Why contemporary Americans accept Catholic or Eastern Orthodox liturgical material culture housed in fine arts museums as art but view these same types of objects placed within actual churches as religion is due to the rise of fine arts museums, the epistemologies of art history that support them, and the art market which supplies them.

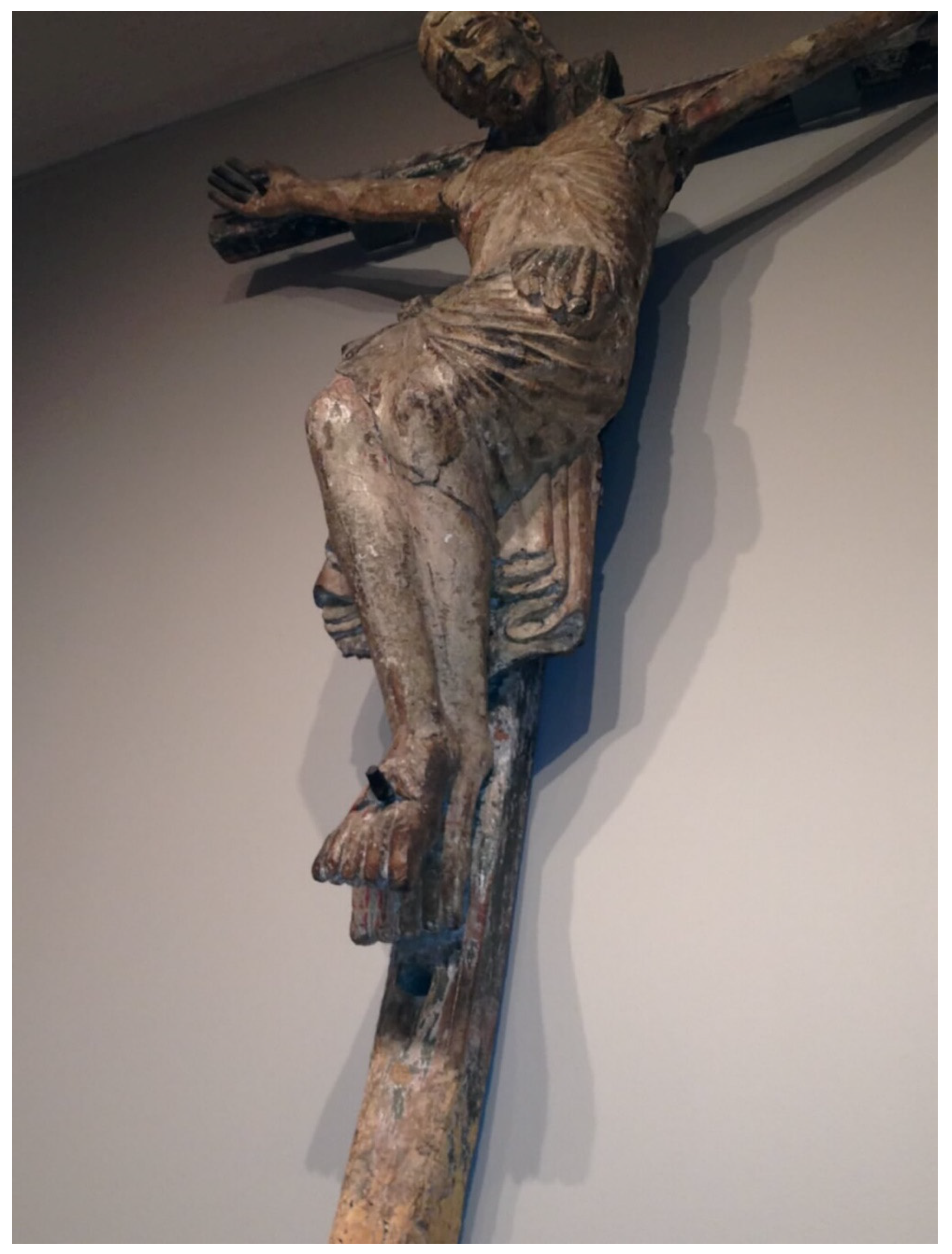

This article offers a specific case study of one particular religious object and the transformations in ideological narratives that circumscribe it as a product to be consumed by a general museum-going audience and explores the concrete channels through which one particular crucifix underwent a transition from a religious object to a secular object in one particular art gallery in a university museum. Thus, the thirteenth-century Spanish Crucifix featured in this article (

Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3 and

Figure A4 in

Appendix A) offers a glimpse into how one ecclesiastical object was transformed from a devotional object used by a rural Spanish Catholic community into a commodity bought and sold on the art market.

1 The Crucifix was naturalized as an object of art at a particular historical moment, and remains art despite the Memorial Art Gallery’s curator’s efforts to improve its religious contextualization.

2 Like so many religious objects in fine arts museums, there are no records surrounding the Spanish Crucifix’s commission, the atelier that produced it, or the particular church that revered it. Beyond the limited contextual information provided on the MAG’s wall label, we know nothing of the Crucifix’s origins. We do, however, know a great deal about the origins of the Memorial Art Gallery.

2. The Emergence of the Memorial Art Gallery

The Memorial Art Gallery stands 100 years proud, it is an art museum known for both its acclaimed collections of world art and its educational commitment to, in the words of founder Emily Sibley Watson, “the edification and enjoyment of the citizens of Rochester”. For 100 years, millions of individuals have come to look and learn, to create and socialize, and to contemplate and be inspired.

—Grant Holcomb, Director of the Memorial Art Gallery (1985–2014).

3

Like other museums that had their origins during the museum movement, the Rochester Memorial Art Gallery was the brainchild of the wealthy elites of its patron city. With social ties to the

Metropolitan Museum of Art (

n.d.) President Robert de Forest and University of Rochester President Rush Rhees, the wealthy Sibley family was in the perfect position to have their name forever attached to a growing municipal arts community in the City of Rochester, New York. The story of the Memorial Art Gallery, like so many other public art museums, is bound to the biographies of the city’s wealthiest patrons (

Duncan 1995, pp. 48–49). Unlike the “great man” narratives attached to so many of the other American arts institutions formed during the Museum Age, it was three women who were responsible for the Memorial Art Gallery formation, collection, and innovation. Emily Sibley Watson (1855–1945), the daughter of wealthy industrialist Hiram Sibley, was the preeminent donor and advocate of the Memorial Art Gallery during its formative years. Gertrude (1868–1922) and Isabel Herdle (1905–2004), the daughters of the MAG’s first director George Herdle (1868–1922) would lead the newly born museum through its most trying years. Gertrude Herdle Moore served as the MAG’s director from 1922–1962 and was the first woman to be elected to the prestigious American Association of Museum Directors, while her sister, Isabel C. Herdle, served as the assistant director and chief curator from 1932–1972.

The Memorial Art Gallery formally opened to the public on 9 October 1913. The inauguration celebration included speeches by President of the University of Rochester, Rush Rhees, and the President of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert de Forest. Both men advanced the common notion of their time that the fine arts foster civil and moral values, provide a civilizing force for the masses, and inspire the sense of human achievement and dignity in the populace. In his remarks at the MAG’s opening, de Forest narrated the history of royal and aristocratic art collection, noting that many of these galleries in their installation and in their use, still bear the impress of this origin and are rather expressions of national, even imperial grandeur, than part of any broad educational scheme. It has remained for the present generation to realize the relation between art galleries and education and to bring art galleries into proper relation to the school and university. It has remained too for the present generation to realize that the fine arts of painting and sculpture, which have been represented almost exclusively in the art galleries of the past, are not only the arts, but only part of a great whole (

De Forest 1913, p. 10).

Affiliated with the University of Rochester, the Memorial Art Gallery’s original mission was to provide an educational service to the municipal community at large, a mission that continued under its former director Grant Holcomb (1985–2014) and has continued under its current director Jonathan Binstock (2014–present).

When the Memorial Art Gallery first opened, it did not have its own permanent collection.

Under the directorship of George Herdle, the Memorial Art Gallery launched its permanent collection with the acquisition of “a lappet of Burano lace, four plaster casts of Greek sculpture, and a group of contemporary American paintings”, according to museum chronicler

Susan Dodge Peters (

1988). After George Herdle retired, his daughter Gertrude, who had been his long-time assistant, was named his successor as director of the Memorial Art Gallery. Under Gertrude, the museum continued to grow, and Gertrude became the first art museum director at a time when the profession lacked statements of professional standards to guide the process of electing a director. In fact, Gertrude and her sister Isabel pioneered exhibitions, educational programming, and community outreach, all with little or no professional training in museum administration, curatorial practices, museum education, or public programming.

Despite their lack of formal graduate training, Gertrude Herdle Moore and Isabel C. Herdle made invaluable contributions during the early years of the MAG’s history that cannot be overemphasized. Art history was a new academic discipline in American universities in the early twentieth century and women attending college were rare. Both sisters attended the University of Rochester and specialized in medieval art. Neither Gertrude nor Isabel received what today would be considered minimal professional museum training, yet they managed to make the MAG an innovator in art collecting and educational programming. Gertrude was responsible not just for the administration of the museum, but also for building donor relations, securing long-term acquisition endowments, and building the permanent collection. The Herdle sisters were strategic in fleshing out the MAG’s collection. Given the growing field of art history in America at the time and the competition among institutions to acquire appropriate art objects to create a viable encyclopedic collection, the Herdle sisters were concerned less about extensive provenance information and more about the affordability, aesthetic value, and educational potential of their acquisitions. Material that entered museum collections prior to the 1970 UNESCO “Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property” often had little provenance information. Isabel Herdle—as chief curator—was responsible for the purchase of the thirteenth century Spanish Crucifix in 1952.

Neither art historians nor scholars of religion have devoted much time to unearthing contextual information related to the MAG’s Spanish Crucifix. This is unfortunate, particularly since such a study might offer specialists in thirteenth-century Catalonian Catholicism a great deal of information about medieval Spanish Catholic religious veneration should such an investigation be undertaken. That said, the limited provenance information provided by the art dealer who sold the object to the Memorial Art Gallery and the information gleaned by careful examination of the Crucifix itself offer a number of important clues as to its original devotional purpose.

The MAG’s medieval gallery is situated at the top of the staircase that brings the visitor to the second floor of the museum. The second floor houses classical antiquities, the galleries for ancient Near Eastern art, Islamic art, Asian art, Renaissance art, and eighteenth-century European art, a central fountain court containing a seventeenth to eighteenth-century organ, and the medieval art gallery. By its central position in the Memorial Art Gallery’s installation of medieval art objects, the Spanish Crucifix is the focus of that gallery.

The MAG’s medieval art collection is small but significant. Most of the artifacts are housed in glass vitrines, though the museum possesses a few medieval paintings. The walls are painted a neutral color that allows the art objects to stand out. Lighting is low to protect the art, but also to help contextualize the objects, as they would have been situated in a darkened church interior or domestic chapel. The Crucifix dominates the gallery. It is hung at an elevated height to mimic its role as an altar cross and on entering the gallery, the visitor’s eyes are immediately drawn to it. All other objects in the medieval art gallery are either at eye-level or contained within glass vitrines. The central placement of the Crucifix above the other objects in the medieval art gallery points to its original sacramental function.

3. The Art Market Claims the Spanish Crucifix

We do not know where the MAG’s Spanish Crucifix was originally created, when it was removed from its Catholic setting, or even why it was preserved. In many cases, churches voluntarily remove items from their interiors to replace them or update them. It is possible that the church which originally housed the Crucifix was closed or damaged, and someone—perhaps even congregants themselves—thoughtfully preserved the Crucifix either in a private chapel or personal collection, but this early provenance information is lost to us. We must construct what can be known about the Crucifix based on stylistic evidence compiled by specialists in art historical analysis.

Stylistic evidence provides us with a limited indication as to where the Crucifix originated and perhaps even when it was carved.

4 The information available to scholars and museum visitors alike is that during the thirteenth century, an alter crucifix was commissioned, carved, and installed in a rural region of Spain. Experts have placed the origin of the MAG’s Crucifix in the Catalonian region, and this geographic designation appears on the object’s 2013 wall label.

Provenance records indicate that the thirteenth-century Spanish Crucifix was transferred from the possession of Barcelonian Olegario Junyent (1876–1956), a painter, author, and set designer, but there is no additional information in the MAG’s registrar’s file to suggest additional insight into how the Crucifix landed in Olegario Junyent’s possession.

5 From Junyent, the Crucifix entered the collection of M. & R. Stora and Company, a medieval art dealer based in Paris and New York. We know nothing of why Junyent sold the work or how it transferred to the art dealers, but we do know that it left Spain prior to the Spanish Civil War, since the object enters the historical record through its inclusion in the

Exposition d’Art Religieux in Nantes, France at the Psallete in July–September 1933 (

MAG Registrar File 52.34 1933).

A stock sheet found among the R. Stora documents (held in the Special Collections of the Getty Research Institute’s Research Library) places the Crucifix in the New York office of R. Stora by 1940. The document appears to note a transfer of the Crucifix from M. & R. Stora Paris, France to R. Stora New York. It is dated 1 May 1940 and states “Stock # N.Y. 702, P.N. 7997”. The stock sheet’s description of the artifact reads, “Big Christ on Cross in wood carved and polychromed. France, 14th Century (Pyrenees-Nord Espagne-12–13th Century)”. A later handwritten addition notes “Crucifix” above the typed “Cross”, and corrects the dimensions as provided in meters. The provenance information includes the 1933 Nantes exhibition, but beneath that typed line are handwritten notes that read, “Olegario Junyent coll. Barcelona” and (sic) “Exhibited in: Minneapolis Institute of Arts Masterpieces of Sculpture No 18 November 1949”. (

Stora et al. 1937–1963).

In 1949, the Crucifix was lent to the “Masterpieces of Sculpture” exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (MIA) as indicated by a receipt that lists the loan price with a date of 17 January 1949, and indicating that the Crucifix was included on the list of objects for the exhibition in

The Bulletin of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (

1949). At this point, the R. Stora firm in New York still retained ownership of the Crucifix since the art dealer is credited as a lender to the exhibition as well as the owner of the Crucifix. Unfortunately, we do not have the museum’s label information for the 1933 Nantes exhibition, but the MIA exhibition catalog lists the Crucifix as “Spanish, 12th century”. A year later in 1950, that same exhibition, “Masterpieces of Sculpture” traveled to Allen Memorial Art Gallery at Oberlin College as a loan exhibition.

6The stock sheet conveniently provided a list of quoted prices offered to potential buyers beginning in 1944, but the Crucifix did not find a permanent home until curator Isabel Herdle approved its purchase on behalf of the Memorial Art Gallery in 1951. The following year, in 1952, the Crucifix arrived at its current home in Rochester, New York.

The Memorial Art Gallery welcomed the Crucifix into its collection by announcing it to the Rochester Community on the cover of its bi-monthly

Gallery Notes (

1953). In the

Gallery Notes, the Crucifix is shown already installed on the Fountain Court wall, flanked with the carved wooden figures of the Virgin Mary and St. John. In medieval chapels, the Virgin Mary and St. John were often included close to a Crucifix and became known as a “Crucifixion Group” in the later art historical lexicon.

The Spanish Crucifix was featured in the MAG’s 1961

Handbook to the Collection. It was included in the “Treasures of Rochester” exhibition held at the Memorial Art Gallery in 1977. In 1988, the Spanish Crucifix was researched by provisional docent Claire Bagale and her report made its way into the official Registrar’s file for the object. Bagale’s prose is mostly lifted from the

Gallery Notes and mistakenly assumes that the Crucifix was removed from Spain during the Spanish Civil War. More recently, the Crucifix was included in

Gothic Sculpture in America III: The Museums of New York and Pennsylvania (

Holladay and Ward 2016). Still, though, there has been no systematic scholarly research done on the Spanish Crucifix either by trained art historians or by scholars of religious studies.

7In 2005, the Crucifix was moved from a central location in the second-level Fountain Wall Court to a side room that became the permanent gallery of the medieval art. This shift was due to the acquisition of a Renaissance organ, which was installed where the Crucifix had previously hung. In 2013, the MAG reinstalled the Crucifixion group after fully refurbishing and upgrading the medieval art gallery. The Crucifix currently resides in this space complete with new wall labels. The updated wall labels indicate that the Crucifix’s origins lie in the Catalonian region of Spain. That is the entirety of the provenance information related to the Spanish Crucifix.

Much of the material with Christian imagery in American art museums dates to the medieval, Renaissance, and Counter-Reformation periods, when the church was the primary donor for and supporter of the arts. It is not news that during the medieval period the Catholic church held sway in nearly every dimension of public life.

8 The church ruled some areas directly and others indirectly, but in urban areas its presence was pervasive. During the Reformations and the social and political conflicts that plagued Europe throughout the sixteenth century, many Catholic churches were closed and their assets seized. Unless members of the Catholic clergy or particular congregations managed to save ecclesiastical implements and devotional images, valuable liturgical implements were confiscated, melted down, and refashioned for secular usage. Other materials were simply destroyed.

During the Reformation and the wars that followed, Spain was a bastion of Catholic solidarity and did not experience the same devastation that plagued other parts of Europe. Even during the Napoleonic era, the rural mountainous regions of eastern Spain did not suffer the fate of seizure and confiscation that befell France and Italy as agents of the French Revolution looted Catholic churches of their treasures. Further, we know that the Crucifix did not fall prey to the secularizing forces of the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) since the Crucifix was already in the possession of M. & R. Stora and Company by 1933. Still, the Catalan region was subject to political and social tensions prior to the start of the war due to conflict between the conservative Roman Catholic camp and the modernizing democratic faction. It is possible that the church from which the Crucifix originated was closed sometime during this period of unrest. The dilapidated condition of the Crucifix itself, however, calls this into question. Likely, the Crucifix was removed much earlier and, unfortunately, not kept under conditions best suiting its long-term preservation. As a result, the Crucifix is not in pristine condition. In fact, at risk of upsetting art historical claims to the contrary, the work is neither a masterpiece nor technically well executed. Though an interesting medieval antiquity and example of rural Spanish craft, how did it earn its status as fine art?

4. The Spanish Crucifix Is Aestheticized and Musealized

To address this question, we might engage a formal art historical analysis of the Crucifix. Beginning with the medium, the Crucifix is carved entirely from wood though the species of particular wood is not known The Crucifix was once painted, but the extent of painting is not evident.

9 With closer inspection, we can see that the MAG’s Crucifix is quite damaged with most of its polychrome is missing. The wood is worn, flaked, and beset with wormholes.

When we consider additional formal elements of the sculpture (shape, line, space, color, and texture), we can conclude that the sculptor or sculptors who carved the Crucifix were working within a particular idiom of Catholic imagery. Medieval sculptors hired by Catholic authorities were not free to re-interpret the figure of Jesus hanging on the cross and were restrained by ecclesiastical injunction. Keeping with thirteenth-century ecclesiastical directives, we have a three-dimensional carved representation of Jesus’ body hanging tautly upon a cross. The figure is clothed only in a perizonium or loincloth, its eyes seemingly closed, and feet nailed together with one nail.

There are several interesting features of this carving that have not yet been mentioned in the museum’s descriptions of the MAG’s Crucifix. First, the dimensions of the cross itself are insufficient for the Corpus Christi hanging upon it—it is too narrow for the size of the figure. Second, the arms, hands, and feet are not proportionate with the rest of the body. Third, the eyes, mouth, nose, and bridge of Jesus’ face are roughly carved (as can be seen in the detail in

Figure A4). The nose was clearly not carved with any realistic precision in scale to the rest of the face.

Without the benefit of being able to see the MAG’s Crucifix fully painted, are we to assume that the sculptor or sculptors who carved this piece had severe technical limitations in terms of artistic expertise? Before drawing any conclusions here, let us consider other elements of the Crucifix. For instance, note the competent treatment of the diagonal lines of the torso, which are echoed in the tilt of the head, the parting of hair, and the drape of the cloth. The vertical line of the cross is mirrored in the folds of the cloth and the sternum, while the perfect horizontal line of Jesus’ garment evokes the crossbeam. The carver was not a master sculptor, but from these details we can draw some important conclusions about this work.

It is likely that this Crucifix was hung high above the sacristy or altar. The overly triangular nose, deeply detailed perizonium, and disproportionate hands and feet indicate that the Crucifix would have appeared to scale only when viewed from below and at a distance, while its painted surface would allow details to be seen from afar. This suggests a professional atelier produced the Crucifix rather than a simple rural or folk workshop.

Anecdotal evidence holds that when the Crucifix arrived at the Memorial Art Gallery, there was a small label attached to it that reads “Ripoll” (a city in the Catalan region of Spain). This along with the Spanish provenance connection to Barcelona places the origin of the Crucifix somewhere in the Catalonian region of Spain. Though there was no written documentation to support this conclusion, the MAG’s Isabel Herdle characterized the Crucifix as Catalonian by its association with the other two figures in the Crucifixion group, the Mourning Virgin and Saint John (52.33.1–2), which were purchased at the same time as the Crucifix. Initially, the Crucifix was dated to the twelfth century and the accompanying figures to the thirteenth century. The dating of the Crucifix was adjusted in the 2013 re-installation. The wall label for the 2013 re-installation reads as follows:

Spanish (probably Catalonia), early 1200s

Crucifix

Wood with polychromy

R.T. Miller Fund, 52.34

Spanish, late 1200s

Mourning Virgin and Saint John

Wood with polychromy

R.T. Miller Fund, 52.33.1–2

Large-scale sculpted groups of the crucified Christ, the Virgin, and Saint John were frequently found in Spanish medieval churches. They were located either above the choir screen that separated the area for the clergy from the main body of the church or against a side wall.

The crucifix dates about 50 years earlier than the pair of the Mourning Virgin (52.33.1) and Saint John (52.33.2). The museum purchased these three sculptures together in 1952 with the intent of representing this important genre of Spanish medieval art.

On the accompanying wall label for the Crucifix, we are given additional information about the two objects which are installed below it, the Mourning Virgin and Saint John. All three artifacts are classified as “medieval” by the MAG and installed in their designated Medieval Art Gallery. Though some visitors may not be familiar with what “medieval” indicates, the dating of the other objects in the medieval gallery places them all within a specific period, c. 500–1500 CE.

In general, the MAG’s wall labels provide the following museological information for each object: the title, the name of the donor who initiated the investment fund through which the works were purchased by the MAG, and the acquisition or registrar’s number assigned to the object.

10 None of this information speaks to the original liturgical, religious, or contemplative purpose of the objects. Instead, these “medieval” objects have been catalogued and systematized as commodities, their religious value overwritten by museal value: title, material, period, donor, acquisition number. While this information is helpful for the MAG’s various museological purposes as well as for students and scholars interested in studying the work, it offers little in terms of the religious use or significance of artifacts.

The Crucifixion group is classified as typical of “large-scale sculpted groups” found in “medieval Spanish churches”. Further, the visitor is told that the Memorial Art Gallery has united these objects to allow visitors to experience the grouping as it would have appeared in many “Spanish” medieval churches. Additionally, the label tells the visitor, “They were located either above the choir screen that separated the area for the clergy from the main body of the church or against a side wall”. This information seems straightforward and simply provides contextualization for the art objects, but it assumes that visitors have prior knowledge of not only art historical terminology (e.g., “polychromy”), but also of Christian, specifically medieval Catholic, ecclesiastical practices.

For instance, the information on the Memorial Art Gallery’s wall label for the Spanish Crucifix assumes that visitors are familiar with the physical layout of medieval churches, understand what a “choir screen” is, and know why clergy would be separated from the “main body of the church”. The pedagogical effect of including this contextual information related to the Spanish Crucifix and the sculpted figures of the Virgin Mary and St. John is curious. This seems to indicate that museum visitors will possess the necessary prior knowledge of medieval Roman Catholic religious practices to understand the original function of these ecclesiastic liturgical artifacts.

In labeling an object “medieval”, fine arts museum curators and educators presume that visitors are familiar with conventional Western art historical classifications for European religious artifacts. This category is reinforced as visitors associate the particular regional, religious, stylistic, and artistic features that have come to be known “medieval” and apply this knowledge to similar objects Further, museum professionals presume that visitors will know Christian, particularly medieval Catholic, liturgical procedures, the architectural layout of medieval churches and chapels, as well as the basic norms of medieval ecclesiastical practice. Since all of this is assumed, there is no need to waste limited and valuable text space on the wall label to explain this information. Instead, the museological information is included: the dimensions, medium, donors, object/accession numbers—none of which indicate the underlying theological purpose of the objects, their original raison d’être. Consequently, the original theological message of the Crucifix, Mourning Virgin, and Saint John has been quietly subsumed into a new story. The objects are presented as a given “genre”, i.e., “medieval sculpture”, as though they are little more than examples of one style or movement alongside many other styles.

After the reinstallation, the Crucifix was assigned a thirteenth-century date (“early 1200s”), while the Mourning Virgin and Saint John are dated slightly later (“late 1200s”). In the initial publication announcing the acquisition of the Crucifixion group, the sculpted figures of the Virgin and John were attributed to a Catalonian origin, but the new label changes this designation with the Virgin and John ascribed more generally to “Spain”, while the Crucifix is now described as likely Catalonian. As specialists continue to research the objects, attributions may necessarily change. The wall label informs us, however, that the objects were purchased as a group despite their having come from different parts of the Iberian Peninsula and being separated by over fifty years.

When the Crucifixion group was first purchased, Isabel Herdle described the group as “Romanesque”. The 2013 label, however, does not offer a stylistic attribution. It does not inform the viewer whether these works are specifically “Romanesque” or “Gothic”. What the label does say instead is that such objects were “frequently found in medieval churches”, and that the MAG purchased the three artifacts together for “representing this important genre of Spanish medieval art”. Of course, no such “genre” of “Spanish medieval art” existed as a category in its own context since such a designation is a product of art history.

For medieval Catholics, these figural representations would not have been considered “art”, (in the modern sense of that term), nor would they have been understood as representatives of a “genre”. Instead, they would have been understood much differently. In Christian theology, the dying Jesus of Nazareth is identified as the divine incarnation of the God the son. The “Mourning Virgin” and “Saint John” are venerated as intermediaries between the divine realm of God, the heavenly father, and the profane world of human concerns. The wall label does not offer specific religious or theological information related to these figures, nor can such information be found in the registrar’s file. What is attached to object in the museum context are stylistic qualifiers. Students and scholars studying these carvings might classify them as Romanesque, or even Gothic.

11The term “Romanesque” came into intellectual parlance in the first half of the nineteenth century as the designation of an architectural style contrasted to “Gothic”. It was during this same period that the term “medieval” also gained traction as an adjective separating the Classical world from the “Renaissance” (

Rudolph 2006, pp. 22–23). According to noted art historian Meyer Shapiro (1904–1996), Romanesque styles of art and architecture that derived from classical Roman architectural forms (such as the arch and buttress) became the favored style architecture in the early medieval period (

Shapiro 1977). However, what is this monolithic “Romanesque art” that is the subject of countless books, chapters, and journal articles—popular and scholarly? How are we to understand an anachronistic term for what has come to be understood as a common style?

Romanesque came to designate a style of art and architecture that seemed common across Christian Europe during the tenth through the twelfth centuries. The term “Romanesque” is so common now in museological taxonomy that little explanation accompanies it, and, it must be remembered, one of the main points we are considering here is how art historical terms have become so naturalized that they no longer need explanation. While the term Romanesque is no longer used to identify the Crucifixion group at the Memorial Art Gallery, the term remains a common art historical stylistic identifier associated with Christian architecture and architectural elements. The Crucifix demonstrates some traits that have been assigned to Gothic, though, such as emotional expression, more realistic perspective, and more natural human postures.

According to the common Western art historical timeline, Romanesque styles eventually give way to Gothic styles in art and architecture. In the art historical narrative, there is little theological information offered to explain the Catholic Church’s transformation of decorative styles, so we might turn to religious studies scholarship. Scholars of medieval Christianity would know, of course, that the thirteenth century was a time of great theological change. Art history textbooks regularly focus on the rise of the cathedral, with particular attention paid to the development of the barrel vault. Impressive though they were, barrel vaults were not the crucial impetus driving medieval piety. Art historical scholarship acknowledges the theological stirrings that manifested in the magnificent cathedrals during the transition from the Romanesque to the Gothic, but its disciplinary focus is on the architectural developments that take precedence in art historical analysis, not the theological programs of the Catholic Church. In general, art historical approaches do not place much emphasis on the different idioms of crucifixes and crosses found in Catholic and Christian worship. They are instead presented merely as decorative elements that reflect a particular region, style, period, or religion—the accepted standard classifications within the Western art historical worldview. However, religious studies might lend some insights to our particular case study of the MAG’s Spanish Crucifix.

Industry is not a term that tends to be associated with medieval Catholic churches, but the term aptly describes the Church’s control over the production of its ecclesiastical and liturgical objects. Medieval Roman Catholic authorities provided strict guidelines for artisans and craftsmen in the production of ecclesiastical materials for use in churches. In effect, they controlled a whole industry of ecclesiastical and liturgical materials. Church art and artifacts were pressed into service of Catholic theology, they were not merely the result of individual genius or interpretation.

In writing about the newly acquired Crucifixion group (see

Figure A1), Isobel Herdle described these objects in the Memorial Art Galleries serial publication

Gallery Notes in terms that border on the reverent.

Acquired through the R. T. Miller Fund, the group beautifully summarizes all the poignant and powerful symbolism of the Passion as conceived in Romanesque iconography and adds the special emotional quality and dramatic intensity that Spain—particularly, Catalonian Spain—gave to its finest medieval work. Here symbolically in the angular distortion and simplified planes of Christ’s bent body and bowed head, in the brooding serenity of the Virgin and the anguished gesture of St. John, man’s long struggle toward faith is given concrete, though abstracted form.

Today, the language would be toned down for contemporary museum visitors, but it was typical for a 1953 American audience and demonstrates the tensions involved in trying to overwrite theological tradition with aesthetic value. In Herdles’ original text, sculptures were identified as “Catalonian” as well as indicative of “the special emotional quality and intensity that Spain—particularly, Catalonian Spain—gave to its finest medieval work”. Again, such language would not be acceptable today, since it universalizes and assigns a particular “emotional quality and intensity” to an entire nation. Note, however, that Herdle was careful not to label the Crucifixion group itself as being the “finest” medieval work, since as we have already noted, this Crucifixion group is not the highest quality of its kind. The Crucifix itself has lost most of its exterior paint. In fact, the Crucifix and its accompanying Mourning Virgin and St. John are rustic and regional. It is primarily the age of the three sculptures that bestows their art historical value and status, which the museum dates to the early thirteenth century.

From the 1996 gallery label text, along with the physical dimensions of the object, we are offered: “Unknown, Spanish, Crucifix, early 13th century, Wood, polychromy, R.T. Miller Fund”, and this exposition:

The crucifix was not a popular theme in the early Christian era, but by the twelfth century, the group of Christ (52.34), the Virgin (52.33.1), and St. John (52.33.2) had become a poignant and powerful symbol of the Passion. Spanish cultures, especially of Catalonian origin, were particularly expressive and emotional. The Virgin and St. John displayed here were not originally with this particular Crucifix, but their stylized features, ovoid heads, and elongated bodies suggest a Catalonian Spanish origin.

12

In May 2012, the new label included the same museological information (materials, acquisition number, and fund), but nothing further than “Spanish, Crucifix, 1200s”.

In June 2013, the medieval gallery at the MAG was completely reinstalled. The faded beige damask fabric wall covering was removed, the walls were repainted in a dark neutral beige, the floors were refinished, and the collection was refurbished with thematic case work installations, the repositioning of some items, and additional manuscripts and textiles were placed on view. With such a small collection, the curator envisioned and executed a successful thematic design that incorporated ecclesiastical and liturgical implements, church decoration and sculpture, and objects of personal devotion. The curator also included new contextual wall labels to fill out details about religious practice and belief in the Middle Ages. With the new contextual information and thematic placement, the reinstallation is visually appealing and informative, and it highlights the MAG’s commitment to educating museum visitors as well as treating all objects respectfully and judiciously.

13 The new wall label for the Crucifix reads, “Spanish (probably Catalonia), early 1200s”. The label provides a more defined regional attribution, but still nothing regarding how the medieval Catholics might have engaged with the objects. This, of course, is a large undertaking. It would be impossible to summarize on a museum’s “chat label” the complex theological evolution of the Christian cross or fully contextualize how medieval Christians might have viewed it. To do this, we might consider exploring the original devotional purpose of the Spanish Crucifix by considering its religious significance in Catholic tradition.

5. The Spanish Crucifix and Critical Religious Studies

The cross—two lines, one vertical and one horizontal, that cross at one point—occurs regularly as a simple geometric shape in nature. The simple cross as a design element or a geometrical pattern occurs across various media, cultures, and epochs. As a geometric figure used by humans, it is at least as old as the Neolithic period and appears regularly in numerous ancient civilizations, including as a component of the pharaonic Ankh and as equilateral crosses found throughout the ancient Indus Valley cultures (

Chevalier 1997). In modernity, variations of the cross appear on countless national flags indicating political rather than religious identity. Such variations of the cross as well as “T” and the “X” occur in nearly every human culture. No dictionary of symbols is complete without some speculation as to the cultural meanings of the cross or crossroads (

Ronnberg and Martin 2010, pp. 716–17).

However, when a cross stands alone, or next to other symbols of religious faiths like the Star of David for Judaism, or the Crescent for Islam, the cross commonly indicates Christianity. In this way, the use of the cross without any further figural decoration serves as a simple icon or shorthand for the Christian faith. In general, it is an indicator of Christianity, or an “icon” in the modern sense of the term rather than a symbol of religious contemplation or ritual. The crucifix, however, is a theological construction that belongs to Christianity alone (

Samuelsson 2011;

Jensen 2017). A crucifix includes the figural representation of the body of Jesus hanging upon a cross, the instrument of his execution. For Christian believers, the crucifix represents Jesus’ sacrifice in atonement for humanity’s sin and evokes a soteriological connotation of Jesus’ death. In other words, the crucifix’s primary

raison d’être is to invoke a theological response, calling forth the main tenet of Christian doctrine for Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, and Eastern Orthodox churches.

14 In short, the crucifix serves as the contemplative reminder of this core doctrine of salvation.

The available literature to general museum audiences on crosses and crucifixes (both scholarly and popular) tends to be rather limited, though this is changing.

15Given the wide variety of extant crucifixes, a comparative taxonomy for popular use would be quite useful for museum audiences. In the future, we can hope that such guidebooks will become available. In the interim, one must carefully observe individual crucifixes to obtain important differentiating details. For example, looking at the MAG’s Crucifix, as discussed above, one can see that the body of Jesus is far too large for the size of the cross itself; this cross would not have supported the weight of a human man. The horizontal beam is too short and too narrow, while the vertical beam stops just above Jesus’ head, and is also too narrow. Apparently, for the sculptor, the original church where this object was located, and its parishioners, realism was of little importance. It was a critical theological emblem that communicated specifically Christian doctrines of salvation, redemption, and sacrifice. As Richard Viladesau notes about an eleventh-century wooden crucifix (similar in some respects to the MAG’s Spanish Crucifix):

The iconography of the cross is complex but at the same time straightforward. The crucified Christ is the incarnate divine Lord [sic], the risen savior, and the eschatological judge. The cross is therefore the tree of life and sign of hope for salvation from the powers of hell, which continue to attack the Christian.

The theologia crucis has evolved over the centuries. By the fifth century CE, the crucis fixus (“one fixed to a cross” indicating the body of Jesus of Nazareth) was a predominant image in churches across both the Latin West and Greek East. In medieval churches that lacked a chancel screen (as did most rural churches and chapels), large crucifixes hung behind and above the altar to remind worshipers of the sacrifice of their savior in atonement for the sins of humankind. Congregants were encouraged to pray before the crucifix, as prayers before it were considered sacramental. At first, only the crucifix itself was installed above the altar, but later, entire crucifixion scenes were added to increasingly ornate and elaborate chancel screens.

The two main theological types of the Corpus Christi used in the Christian imagery during the late Romanesque and early Gothic periods have come to be labeled by art historians as the

Christus Triumphans and the

Christus Patiens. Such art historical stylistic terminology, however, severs the theological links between crucifixes and Christian theology a bit too neatly. The theology of the

Christus Triumphans demonstrates Jesus’ triumph over death. In this type—the earliest—the crucified Jesus does not appear to be suffering and is instead looking out at the viewer with a peaceful gaze. Jesus’ body does not droop on the cross, pulled downward by its own weight, but is straight and upright and, often, clothed in a longer or knee-length perizoma. Further, Jesus appears to be standing, supported by some invisible force, while his eyes are bright and calm, and a slight smile graces his countenance. In general,

Christus Triumphans is nailed to the cross with four nails—one through each hand and each foot in the tradition established by

Gregory of Tours (

1988, pp. 538–94) in his

Glory of the Martyrs.

The second type, the

Christus Patiens, developed later, by the tenth century. This type was contemporary with the

Christus Triumphans although it tended to replace the triumphant version in the Latin West when thirteenth and fourteenth-century theological trends in Europe began to focus on the suffering of Jesus. In the second type, Jesus’ suffering is portrayed often in excruciating detail. His eyes are closed and his angled body sags painfully under its own weight. He is emaciated, his musculature strained, and his skin ashen in either gray or green hues. In early medieval art imagery, Jesus was portrayed with the customary four nails, but in later depictions, the convention of three nails was used, with his feet attached to the cross by a single nail. The

Christus Patiens type became the dominant form in the Latin churches of the West, particularly after the rise of the Franciscan Order in the thirteenth century. However, according to Oleg Zastrow, it was during the Gothic period that Christian visual narratives more frequently depicted images of Jesus’ crucifixion scene drawing attention to his suffering and torture on the cross (

Zastrow 2009, p. 26).

This transition from four to three nails in crucifixion imagery has garnered little attention on fine arts museum gallery wall labels. Thus far, neither scholars of Christianity nor theologians have paid much attention to this transition.

16 Since the Church maintained strict guidelines for its ecclesiastical ateliers, it is reasonable to suggest that theological trends precipitated the transition, but this issue remains a topic of investigation for specialists in thirteenth-century theology and cannot concern us further here. What can be known about crucifixes is generally limited to the specifics, and, even here, like many other artifacts, scholars are left to sift through meager contextual information, particularly when these objects come from rural areas of Europe.

In its original religious purpose, a crucifix was designed to function as an object of contemplation, to communicate the complex doctrine of sacrifice, salvation, and redemption to the Christian faithful. Churches often housed flatworks (e.g., paintings and frescoes) among their ecclesiastical decoration and with the rise of the Church’s power and prosperity across Europe, new and more lavish visual depictions of both Old and New Testament narratives graced church interiors. The crucifix, however, remained the central theological emblem of the faith.

The MAG’s Crucifix and the Mourning Virgin and St. John were created for different rural churches during the 1200s. These are clearly not the most expensive or elaborate sculptures from the Iberian Peninsula. The theological purpose of these sculptures would have been to move congregants into a contemplative, deferent attitude in the ritual observance of the Catholic mass or regularly daily services, and to remind viewers of the soteriological significance of Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross. The styles of worship in the eastern region of Spain were closely aligned with the Abbey of Cluny (Cluny, France), particularly the two main monastic centers of Santa Maria de Ripoll and Santa Maria de Montserrat. In fact, the most eastern Catalonian See of Vich preserved its Benedictine culture despite the Muslim presence in the rest of Spain (

O’Callaghan 1975).

Given the size of the MAG’s Crucifix, it is likely that it would have been hung above an altar or affixed to a rood beam or a chancel screen. Since the figure is carved only in the front, it is unlikely to have served in liturgical processions. Further, its verso is not decorated. Specialists have identified the MAG’s Crucifix as having originated from the Catalonian region of Spain. This assessment is based on its stylistic features as well as anecdotal evidence. Specialists in Spanish and Catalonian art have focused on its formalistic features, noting that the ovoid shape of Jesus’ head reflects a stylistic preference common in Catalonia. However, this does not necessarily indicate a Catalonian origin, as other rood crucifixes also have variously shaped heads. Another medieval Iberian crucifix (roughly contemporary with the MAG’s) in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has a similar head shape, but its attribution is simply “North Spanish”. Consequently, other than to fit the object within an art historical stylistic and geographic taxonomy, one wonders what the importance of identifying its origins of might be. What additional information does this provide about the object itself, particularly when the contextual significance of the object’s period and region continues to be overlooked on museum wall labels?

6. Conclusions

The epistemological transformations that religious material culture undergoes as meanings shift from contemplative practice to aesthetic product has deeply changed the way liturgical objects have been interpreted. Visitors to the public, secular Memorial Art Gallery interact with the Spanish Crucifix visually and aesthetically through the lens of art history rather than through the contextualization of its historical religious significance. Whereas in Catholic devotion, each gesture of the Corpus Christi was invested with deep theological implications, in art historical aestheticization and musealization epistemologies, the object’s aesthetic qualities are highlighted. Art historical terms and conventions frame the MAG’s Crucifix for viewers, who might then move on to the next item in the gallery and never receive the opportunity to enrich their understanding of any one art object’s deeper contextual significance. As such, “medieval” continues to be an art historical adjective that obscures the complexity of the society, the various conventions of medieval Corpora Christi, and the many variations within Christianity.

The original meanings and significance, then, of the Spanish Crucifix reside in its theological, rather than its regional or stylistic designations. Therefore, what has been included in the art historical description of the object offers us nothing more than a trace—an absence. Like the archaeologist arriving long after tomb robbers have ransacked a site, religion scholars are left to reconstruct medieval piety from objects removed from their original settings, lacking in both context and documentation. The trace points to the wide gaps in our understandings of the use of crucifixes in the medieval period in rural areas.

For example, when museum visitors are introduced to medieval Christian art, they are rarely, if ever, told to compare the typology of crucifixes or consider the subtle differences that occur in crucifix imagery, and there are indeed many. Museum visitors’ attention is directed to period, geography, and form. Important contextual information is missing. Museum viewers rarely think about whether Jesus is portrayed having been nailed to the cross with four nails, one in each hand, and one in each foot, or three nails, one per hand, with one nail piercing both feet, one foot crossed beneath the other. This could simply be a stylistic development, or it could reflect shifting theological currents occurring in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

When viewed merely as a commodity or product, details related to the historical and religious significance of religious material culture are often overlooked. Visitors are rarely, if ever, encouraged to consider the theological implications of medieval imagery outside of hagiographical attributes. Yet, the variations of crucifix imagery clearly reflect particular theological agendas, for example, the treatment of Jesus’ arms or whether he is portrayed with his eyes open or closed. Is the head upright and straight? Is it dropped to the side, indicating agony? Is there a crown and, if so, is it a crown of thorns or the royal crown of a king? Is there a halo or aureole? Is Jesus visibly dying or dead, or alive and powerful? Are the traditional five wounds apparent? How is Jesus clothed, fully robed or in little more than a loin cloth? How is Jesus attired, luxuriously or scantily? What about Jesus’ musculature? Are his ribs visible? Are his limbs pulled taunt, with muscles stretched and torn, or is Jesus in full command of his limbs? Is he seated on a verso, the ledge beneath his buttocks, or is the verso missing? Is Jesus bearded or clean-shaven? Is his hair short, long, curly, straight, dark, or light? How has Jesus been crucified, with four nails or three? Is his mouth open or closed? Is there a sign above his head—either the INRI sign or another? Are there additional images carved or painted up on the cross?

All these details are important indications of the Christology shaping the communities in which these crucifixes were originally produced. Yet, this information is rarely—if ever—conveyed to museum audiences. Audiences are left with the impression that all medieval Christians shared the same beliefs and represented their savior in the same way, despite overwhelming evidence of difference and variance even within the same geographic region, yet each hand-carved crucifix follows ecclesiastical dictates and can be as individual as the community that produced it. In reviewing religious material culture held in fine arts museums, critical religious studies methodologies can enhance the contextual complexity of liturgical objects to produce richer presentations of material that is both art and religion. Though we looked at one example in this article, the contextualization of religious material culture from other religious traditions held in fine arts museums might also benefit from interdisciplinary inquiries and scholarship.