Abstract

In theory, the coronavirus pandemic, with its wide-ranging implications for the functioning of societies around the world, cannot fail to have an impact on religiosity. We test whether this is really the case and investigate the scope and trend of changes in religious commitment using the example of Polish society. We make use of survey research conducted at various times on representative samples of Poles. Many studies have shown that in the face of destabilization and uncertainty, religious engagement gives hope and support, and therefore religiosity should be expected to increase during a pandemic. On the other hand, it can be assumed that a superficial and traditional religiosity, associated only with customary participation in Sunday religious practices, may weaken or even disappear when churches close. It emerges that both these phenomena can be observed in Polish society and, consequently, in the context of the pandemic, they are leading to religious polarization.

Keywords:

pandemic; Poland; SARS-CoV-2; religion; religious practices; secularization; religious polarization 1. Introduction

As a rule, any change that significantly transforms social, political, and economic life also affects the sphere of faith and religiosity. As Peter L. Berger (1984) notes, “just as religious ideas can lead to empirically tangible changes in the social structure, changes in the social structure affect the level of religious awareness and perceptions. Religion appears as a shaping force in one situation and as a dependent phenomenon in another historical situation”. In this context, the coronavirus pandemic, with its broad implications for the functioning of societies around the world, could not in theory fail to have an impact on religiosity.

Functionalists suggest that religion is important to both society and the individual because it has both explicit and implicit functions. Among the many functions assigned to religion, they indicate religion as a source of emotional support and answers to final questions, including those related to explaining events that seem difficult to understand (Durkheim 1898; Malinowski 1990). Religion is supposed to provide the means by which a person can bravely face crises and adversities (Kahana et al. 1988).

Religion, by providing a frame of reference that exceeds the empirically available “here and now”, often remains a support for individuals in a situation of uncertainty of fate, in failures, and in disappointments. Religion includes people in a group integrated by recognized values and norms and thus contributes to an increase in social control and a reduction in deviation. Religion fosters self-definition (identification) and leads individuals through various phases of life (Sroczyńska 2018). In the face of cataclysm, destabilization, and uncertainty, religion becomes more important and offers hope and support (Bentzen 2019) and, conversely, augmented security contributes to the growth of secularization. This is especially visible in the modernized Western European countries, where people live under conditions of greater security and do not need predictable and rigid rules of conduct (Norris and Inglehart 2011). Sociologists of religion have shown that increased financial, social, and existential security associated with the modernization process result in a decreased need for religious reassurance (Höllinger and Muckenhuber 2019; Immerzeel and van Tubergen 2011; Molteni 2020; Norris and Inglehart 2011).

Religiousness also promotes better physical health, and some studies even show that religious people live longer than those who are not religious (Moberg 2008) due to the fact that religious people cope better with various diseases (Büssing et al. 2009; Bonelli 2006). Religious commitment also contributes to greater psychological comfort. Religion is sometimes referred to as a kind of supportive psychology—a form of psychotherapy. God gives hope, and this perception helps sufferers alleviate their personal or social crisis. Faith and religious practice can improve mental well-being by being a source of comfort to people in difficult times and by improving their social interactions with others in places of worship. Many studies show that people of all ages, not just the elderly, are happier and more satisfied with their lives if they are religious. They are less likely to become depressed, and those who do have a faster remission (Bonelli et al. 2012; Mahdanian 2018; Büssing et al. 2009; Koenig et al. 1988).

Bearing in mind the above findings, we can suppose that in the global public health crisis we are currently facing due to the COVID-19 pandemic, religion may play a particularly important role in helping people better cope with the threat they are experiencing. On the other hand, the struggle with the pandemic has forced most countries to introduce a number of restrictions to stop the transmission of the virus, including restrictions related to religious worship, and these have certainly not been conducive to the development of religiosity as they have limited its forms.

The uncertain impact of the pandemic on religiosity has been confirmed by the results of research that have already been published. On the one hand, we can observe the growing importance of religiosity. In March 2020, the share of Google searches for prayer surged to the highest level ever recorded, surpassing all other major events that otherwise call for prayer, such as Christmas, Easter, and Ramadan. The level of prayer search shares in March 2020 (The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on 11 March 2020) was more than 50% higher than the average during February 2020. The rise in prayer at the beginning of the pandemic was a global phenomenon, with all countries (except the least religious 10%) seeing significant rises in prayer search shares (Bentzen 2020b). It has also been indicated that people experiencing fear, suffering, or illness in a pandemic often experience a “spiritual renewal”. Therefore, some authors speak of the formation of a new “coronavirus generation”, in which the development of spirituality creates a mature attitude based on truth and freedom (Kowalczyk et al. 2020). A similar phenomenon has also been confirmed by the results of the international Pew Research Center study, according to which many people around the world, especially in the United States, state that the outbreak has boosted their faith (Pew Research Center 2020). Brazilian research has also shown an association between religiosity and spirituality and the positive mental health consequences of social isolation (Lucchetti et al. 2020). Italian findings also suggest that under dramatic circumstances a short-term religious revival is possible, even in contexts where the process of secularization is ongoing. However, it only applies to people who suffered from the most severe effects of the crisis and those who are already religiously socialized (Molteni et al. 2020).

On the other hand, we have evidence of a de-intensification of religious practices during the pandemic. The decrease is greater in regard to institutionalized rites than personal ones. People who previously practiced religious acts with little regularity tended to abandon them during this period (Meza 2020). In South Korea, all three of the country’s major religions (Catholicism, Protestantism, and Buddhism) suffered significant losses in both income and membership, accelerating the already-decreasing influence of institutional religion within Korean society (Park and Kim 2021).

In the context of ambiguous results of research on the transformation of religiosity in the pandemic context, the question is whether and how the pandemic period changed the religious engagement of Poles. In our article, we analyze the scope and trend of changes in religious practices in Polish society, whose attachment to religion (mainly Catholicism, in Poland over 90% of the population are Catholics) has been exceptionally strong in comparison with the rest of Europe—so far. Importantly, however, the relatively high level of Poles’ religious commitment does not mean that there has been no change in Polish religiosity or progress toward secularization. There has been a gradual emancipation of various areas of social life from the influence of the Church and religion, and, thus, on the one hand, a slow departure from faith and religiosity (atheization), and, on the other hand, the individualization of religion, which means that religiosity becomes religiosity by choice—more personal and less institutionalized.

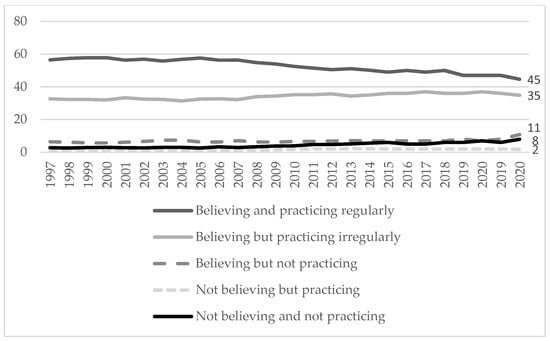

Secularization and individualization trends in Polish religiosity began to appear after Poland joined the European Union in 2004. This was a time that additionally coincided with the death of John Paul II, who had been an exceptional authority for Poles and undoubtedly attracted people to church. After 2005, declared participation in church rituals slightly but systematically decreased, reaching values significantly lower than those recorded during the Pope’s lifetime. The signals are particularly clear in the case of young people, residents of the largest cities, and people with a higher education (CBOS 2015). From 2005 to today, the percentage of Poles who define themselves as believers and who regularly practice religion (at least once a week) has decreased by 13% (from 58% to 45%). At the same time, the numbers of believers who are non-practitioners increased (from 7% to 11%) as did the numbers of non-believers who are non-practitioners (from 3% to 8%). Among people aged 18–24, these trends are even more telling. From 2005 to 2020, the percentage of believing and regularly practicing youth over 18 decreased from 51% to 28%. At that time, there was a 16-point increase in the percentage of non-believers and non-practitioners in this group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The faith and religious practice of Poles—changes over time. Source: own work on the basis of CBOS data.

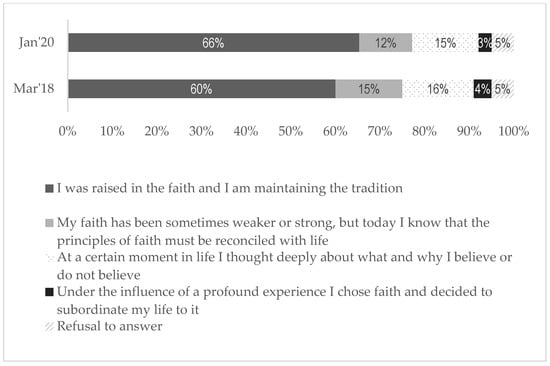

Poles’ declarations of faith have changed much more slowly than their declarations relating to religious practice (invariably, over 90% of Poles describe themselves as Catholics and almost the same percentage consider themselves believers). However, the turn toward a more individualized and simultaneously less institutionalized religiosity, not requiring attendance at Sunday mass, seems quite obvious. The selectivity and individualization of Poles’ faith is also visible in the doctrinal dimension. While considering themselves to be believers and even regularly participating in religious practices, they often not only do not accept many basic tenets of the faith but also frequently hold ideas that are contrary to the Catholic religion. Thus, model institutional religiosity—manifesting itself through an attitude fully reflecting identification with the doctrine of the faith and full acceptance of religious moral norms, confirmed by systematic participation in religious worship and with a simultaneous personal experience of religion and commitment to the religious community—has significantly declined in importance in Poland since 2005 (CBOS 2020e). The religiosity of Poles is largely based solely on the cultivation of tradition. In January 2020, as many as two-thirds of adult Poles surveyed by CBOS, in defining their faith, chose the answer, “I was raised in the faith and am maintaining the tradition” (66%). Not quite one in three respondents (30%) described their faith as “deep”; of these, a majority (15%) stated that at some point in their life they had thoroughly thought about what and why they believed or did not believe. One in eight admitted that their faith had been sometimes weaker or stronger, but said that today they know the principles of faith must be reconciled with life. Others (3%) had chosen faith under the influence of a profound experience and decided to subordinate their life to it (CBOS 2020d). In the course of not quite two years, Poles’ convictions about the traditional nature of their faith increased by six percentage points, and the percentage of those who declared having a deep faith decreased by the same amount (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Traits of Poles’ faith—changes over time. Source: own work on the basis of CBOS data.

Due to the fact that the faith of most Poles is rather superficial, predictions about changes in Polish religiosity have long assumed an increase in atheistic or indifferent attitudes toward religion and the loosening of ties between Polish identity and religious participation (Mariański 2007). These predictions were justified by systematically collected empirical data, although the trend was not clear; hence, the term “creeping secularization” appeared in relation to Polish religiosity (Mariański 2018). However, the year 2020 arrived, and with it the coronavirus pandemic, which has brought about many changes and unknowns, as well as numerous restrictions, including those concerning public religious practice. In this connection, another question arises: how will the pandemic affect the religious engagement of Poles? Will it strengthen it, weaken it, or maybe change it in yet another, non-obvious way?

The Polish government reacted very quickly with specific measures to limit the number of COVID-19 cases. The first restrictions were introduced in mid-March, when the number of diagnosed infections was only 31 cases (Ministry of Health 2020). The quick and decisive reaction of the government most likely caused the number of diagnosed cases in Poland to remain relatively low for a long time. The low number was also thanks to citizens who, especially in the initial phase of the pandemic, very strictly followed the government’s recommendations (CBOS 2020c). As in other countries, the restrictions introduced by the Polish government in connection with fighting the pandemic applied to many spheres of human life, including public worship. Among other things, pilgrimages and religious meetings were canceled, and restrictions were placed on the number of believers allowed to participate in public religious rites (details in Table 1).

Table 1.

Government COVID-19 restrictions in Poland affecting religious practice.

In this new situation for all, religious actors have had an important role to play—including in adapting rituals to the changing restrictions, ensuring the safety of gatherings, and identifying and responding to the needs of the faithful. In line with the guidelines on social distancing and isolation, religious communities around the world, including in Poland, have responsibly modified their religious practices, moved congregations online, and undertaken to provide additional forms of spiritual support for their followers, including through new technologies.

It is worth noting, however, that religious practices in cyberspace provide a different experience than does a gathering of believers in a church, and believers therefore treat those practices as a substitute for religiosity. Much skepticism has been expressed about the possibility of having spiritual experiences through mass media (Hojsgaard and Warburg 2005). In this context, it has been forecast that while the coronavirus pandemic might indeed strengthen a religious attitude to coping with the situation, the closing of religious institutions will result in a shift from public to private prayer (Bentzen 2020a), and thus toward what Thomas Luckmann many years ago called invisible religion (Luckmann 1967)—a religion that is individualized and non-institutional.

The aim of our article is to discuss our findings on how the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns have influenced the narrowly defined religiosity of Poles. We will present, among other matters, aspects of religious practice in Poland under various forms of government restrictions related to combating the coronavirus. We will consider to what extent and in which social groups religious engagement has changed during this period and the nature of these changes.

2. Materials and Methods

This article is based on data on the impact of the pandemic on the religiosity of Poles from cyclical surveys conducted by the Public Opinion Research Center (CBOS) on representative samples of adult Polish residents whose names were drawn from the Universal Electronic System for Registration of the Population (PESEL) register. We are particularly interested in the results of two studies conducted in May 2020 and September 2020, in which the topic of religiosity was addressed in depth. The research procedure in both cases was mixed-mode: each respondent selected for the sample from the PESEL survey independently chose one of the following methods:

- a direct interview with an interviewer (the CAPI method);

- a telephone interview after contacting a CBOS (CATI) interviewer (the respondent received contact details in the CBOS announcement letter); or

- self-completion of an online survey accessed on the basis of a log-in and password provided to the respondent in the CBOS announcement letter.

In all three cases, the questionnaire had the same set of questions and structure. As mentioned above, the surveys were conducted at two different stages of the development of the COVID-19 pandemic. The first—the study “Current problems and events” (359)—was carried out between 22 May and 4 June 2020 on a sample of 1308 people (including 61.6% using the CAPI method, 24.4% using the CATI, and 14% using the CAWI). The second—the study “Current problems and events” (363)—was carried out from 7 to 17 September 2020 on a sample of 1149 people (including 68.0% using the CAPI method, 20.1% using the CATI, and 11.9% using the CAWI). The basic results of both studies were published in CBOS announcements (CBOS 2020a, 2020b). For the purposes of this article, in addition to the previously published reports, we had raw data sets that enabled us to perform additional, more in-depth analyses.

It should be emphasized that in the above-mentioned research, and thus in our article as well, religiosity is treated quite narrowly and in one dimension, as declarations of faith and religious practices occurring in a collective form, or of a traditional nature, as participation in religious rituals in churches, or of a modern nature, as e-religiosity involving participation in religious practices through mass media, including the internet.

Due to their methodological specificity, the results of quantitative research, such as those on which our considerations are based, most often do not touch on the deeper strata of religion and religiosity, such as the very understanding of religion, its meaning, or the consequential dimension, which are usually complex issues requiring in-depth qualitative research. It should be noted that the results presented here concern the faith and religiosity of all Poles, without distinguishing religious minorities and non-believers, given their very limited number in the samples.

In our article, we have adopted a descriptive research approach. Based on the available research results, we analyze the changes in the religious commitment of Poles in the context of the pandemic. We assumed that this historic moment could change the religious landscape in several different ways (Baker et al. 2020).

Therefore, we check to what extent and in which groups of Poles the pandemic has produced an increase in religious engagement. On the other hand, we diagnose—as far as possible based on the available research—to what extent and in which groups restrictions on access to collective religious worship, and the exemption from the obligation to participate in religious practices, weaken the ritual dimension of religiosity and cause a departure from religion.

It should be emphasized that we analyze the changes in religiosity in the context of the pandemic, taking into account the period of the research conducted, but it must also be noted that in that period there were also situations not directly related to the pandemic that could additionally have influenced changes in religious commitment, especially among young Poles. The “Women’s Strike”, which aimed to overturn the Constitutional Tribunal’s decision in regard to abortion in Poland, for which the Church was blamed, should be mentioned in this connection, along with successive disclosures concerning pedophilia in the Polish Church and the failure of bishops to act in the matter.

3. Results

During the first wave of the pandemic, which was characterized by the greatest limitations on social life and thus also religious life, three quarters of Poles declared that in the initial months (April–May) their religious engagement was at the same level as before (75%) (CBOS 2020a). Those whose religious engagement changed in the first phase of the pandemic were slightly more likely to say that their religiosity increased (12%) rather than decreased (10%). A small number (3%) were unable to answer this question. Increased religious engagement was mainly experienced by people who, prior to the pandemic, usually attended mass or services once a week or more often (from 18% of those declaring participation once a week to 47% of those participating in religious practices several times a week).

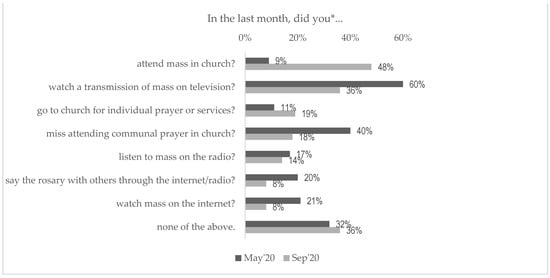

Among the religious activities that the respondents were asked about at that time (CBOS 2020a), the most popular was watching mass on television; almost two thirds of Poles replied that they had done so at least once in the first phase of the pandemic. Two fifths of the respondents (40%) felt the lack of communal prayer in a church. Online broadcasts of mass were attended (at least once) by every fifth Pole (21%), while 17% of respondents declared that they had listened to mass on the radio around the end of May and the beginning of June. During times of social isolation, more people prayed with others through technology: one in five had done so at least once (20%). One in nine people attended individual prayer or church services during the pandemic (11%), and slightly fewer (9%) attended mass in a church, even when the permitted limit was five believers. Almost every third person (32%) did not indicate having engaged in any of the above-mentioned behaviors. Among people who consider that they do not generally participate in religious practices, 16% had watched mass on television, 3% had listened to mass on the radio, and 3% had prayed with others via the Internet, radio, or television.

Over time, along with changes in the restrictions, the religious behavior of Poles changed. During the September study, there was no limit on the number of people who could be in church simultaneously, but the daily number of COVID-19 cases was several times higher than in May. Consequently, Poles returned to churches—but only partially (not on the same scale as before the pandemic). The reason people might not have attended mass physically, despite the possibility, might be real fears for their health, or it might also be partially due to their having abandoned religious practices, as indicated by the increase in the percentage of people who did not declare having participated in any of the above-mentioned religious behaviors (from 32% to 36%), including those behaviors that did not require a physical presence in church (details in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Religious activity of Poles during the pandemic. * In the May study, the question was “Did you attend mass in a church even when the limit was five people?”. Source: own work on the basis of CBOS data.

In May, Poles took part in an average of 1.77 of the religious activities included in the survey. The largest proportion (19%) indicated two behaviors, 17% indicated one behavior, and 16% indicated three behaviors (CBOS 2020a). A regression analysis (ANOVA: Sum of Squares = 1314.042; df = 5; p < 0.01) showed that many variables that generally affect religiosity, such as age, urban residence, household income, and previous rate of participation in religious practices, significantly explained the number of activities undertaken in this case as well; only education turned out to be statistically insignificant (p > 0.05; details in Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of linear regression analysis of the religious engagement of Poles during the pandemic at two time periods (method: enter; dependent variable: number of religious activities).

However, it is worth adding that the model containing all the above-mentioned variables explains a total of 51% of the variability in the number of behaviors and 48% of the frequency of practices alone. There was a strong correlation between the number of religious behaviors in the first phase of the pandemic and the frequency of participation in religious practices (Spearman’s rho = 0.726; p < 0.01). Among people who practiced several times a week before the pandemic, the average number of activities indicated was 3.9; in the group of Poles practicing once a week, the average was 2.7; and among the respondents who participated in mass a few times a year, it was only 0.8 (CBOS 2020a).

In September, the average number of activities the respondents undertook in religious life dropped to 1.52, and most often (21%) only one behavior was indicated (CBOS 2020b). Slightly fewer people (19%) declared that they had undertaken two of the activities mentioned in the last month, and 13% indicated three. Regression analysis (ANOVA: Sum of Squares = 846.145; df = 5, p < 0.01) proved that apart from age and the earlier frequency of participation in religious practices, the education of the respondents also had a significant impact on the number of religious activities in September (p = 0.041). On the other hand, place of residence and household income per person, which generally differentiate the religiosity of Poles and had a significant impact on the number of religious behaviors in May, turned out to be statistically insignificant in September (p > 0.05). Three significant variables accounted for 42% of the variability in the number of behaviors, and frequency of participation in religious practices in September accounted for 36% of the variability, so it was still crucial, but its importance turned out to be less than in May. In addition, the correlation between the number of religious behaviors and the frequency of participation in religious practices was weaker than in May (Spearman’s rho = 0.654 p < 0.01). Among people who practiced their religion several times a week, the average number of activities indicated was 3.1, which is less than in May. In the group of Poles practicing once a week, the average was 2.4 and was similar to May, and among those who usually attended mass a few times a year, it was the same as in the period of greatest restrictions (0.8). Thus, over time, the religious commitment of those people who previously practiced at least once a week had changed, while the commitment of those who were non-practitioners before the pandemic had not changed.

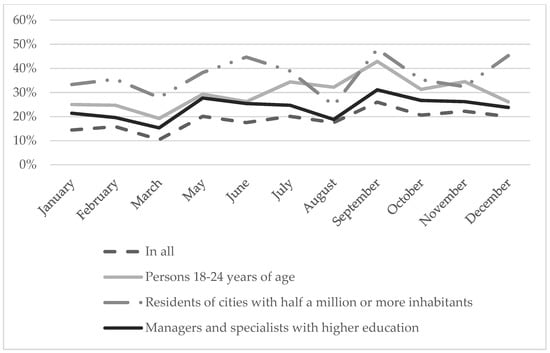

While the spring survey was underway, the restrictions on being in church were changed; the limit on the number of people was eliminated, but the requirement to cover one’s mouth and nose and maintain social distance was continued. Despite the significant easing of restrictions, most of the respondents did not return to practicing in a non-virtual church immediately after the change. Nearly three quarters (73%) of Poles answered “no” to the question “Have you attended mass since the elimination of the limit of five people in a church?” Among the rest, the most common answer was “Yes, several times.” This answer was chosen by almost one fifth of respondents (18%). One in twelve had been to church only once in the period (8%). The respondents who declared that they had not been to church yet were asked when they planned to attend mass. A significant part (39%, that is, 33% of all respondents) stated that they did not plan to return to church at all. At that time, such answers were most often provided by the youngest respondents (50% of people aged 18–24), residents of cities with a population of half a million or more (65%), managers and specialists with a higher education (48%), students (52%), and people with leftist views (57%) (CBOS 2020a). Long-trend data confirm that in these groups there was an increase in the share of non-practicing people in the second half of 2020. In the months of January 2020 to March 2020, a certain decrease in the percentage of people not participating in religious practices was observed, maintaining the same trend in general and in the groups analyzed, while in the following months there was an increase in the number of non-practitioners until September (with a slight decrease in August), and then there was a slight fall again in December (in favor of the answer “Several times a year”, which may be related to participation in Christmas mass). A similar trend was visible in all the groups analyzed, with a certain exception for residents of the largest cities, among whom December brought an increase in the percentage of non-practitioners (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Percentage of people answering “I do not practice at all” in selected groups at the end of the succeeding months of 2020. Source: own work on the basis of CBOS data.

The September CBOS poll deepened the issue of the religious engagement of Poles in relation to the experiences of the last month. It was a time when—except for in a few red zones, where there were restrictions on the number of people who could congregate in churches—only covering one’s mouth and nose and maintaining social distance were mandatory in churches. Throughout the period from the previous survey (carried out at the end of May and the beginning of June), Poles were able to participate quite freely in masses, services, and religious meetings. It emerged, however, that in comparison with the period of greatest restrictions in March and April, the religious engagement of the majority of Poles had not changed over time (CBOS 2020b).

In September, more than half of the respondents (56%) answered that they were devoting as much time to prayer, meditation, and other religious practices as at the peak of the first wave of the pandemic, and almost a quarter (23%) declared that, as before, they did not participate in religious practices at all. Among those whose engagement changed between April and September, the response “Now I spend less time praying...” was twice as frequent (13%) as “Now I spend more time praying...” (6%). The highest percentage of “Now I spend more time praying...” responses was among people who, before the pandemic, generally practiced several times a week (17%), while a decrease in religious engagement compared with the period of greatest restrictions was most often declared by respondents who, before the pandemic, generally practiced once or twice a month (26%) or a few times a year (24%).

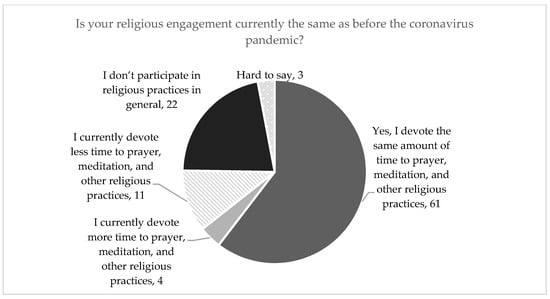

The September survey shows that six months after the beginning of the pandemic, the vast majority of Poles (83%—both practicing and non-practicing) were convinced that their religious life had not changed as a result of the events. More than three fifths of the respondents (61%) believed that they devoted the same amount of time to prayer, meditation, and other religious practices, and 22% declared that they did not participate in practices at all but neither had they participated in religious practices before the pandemic. Importantly, however, among those who observed a change in themselves, a decrease in religious commitment (11%) was almost three times more frequent than an increase (4%, details in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The influence of the pandemic on the religious engagement of Poles. Source: own work on the basis of CBOS data.

A particularly high percentage of responses confirming an increase in the amount of time devoted to prayer and other religious practices was noted among people who attended mass and services several times a week before the pandemic (18%), while a decline in religiosity due to the pandemic most often concerned people attending masses, religious services, or meetings once or twice a month (20%) or a few times a year (19%). Logistic regression analysis in regard to people who declared that their religious commitment increased under the influence of the pandemic (versus others) showed that of all the features that usually affect religiosity, only lower education and previous frequency of participation in religious practices significantly contributed to the increase in religiosity during the pandemic (χ2 = 35.826, df = 8, p < 0.01; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.143, details in Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of a logistic regression analysis of predictors of increased religious engagement under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The September study was carried out at a time when the daily number of coronavirus cases did not exceed 1000, and apart from the obligation to cover one’s mouth and nose and maintain social distance in church, there were no additional restrictions on religious life. The number of believers in churches was limited to 50% of the places only in the few powiats located in the so-called red zone. Under such conditions, 31% of Poles declared that they participated in masses or church services once a week, and another 4% said they participated more often. One out of eight respondents attended church once or twice a month (12%) and a similar percentage (13%) went less frequently. Significantly, two fifths of Poles (40%) declared that they had not attended church services at all after the lifting of the limitation on the number of people in church. We found that among those surveyed, one in four (25%) had watched a televised broadcast of mass at least once before the September survey; 7% of respondents in this group had listened to mass on the radio, and 4% had watched broadcasts of mass online. One in nine people missed being able to attend communal prayer in church (11%); 5% prayed—for example, the rosary—in communication with others (via radio or the Internet), and two out of every hundred people went to church to say individual prayers (2%). A total of 69% of respondents did not indicate any activity.

Comparing the respondents’ declared frequency of participation in religious rituals before the pandemic and after the lifting of restrictions associated with the first wave of the pandemic, in September—when the daily number of cases did not exceed 1000 and apart from the obligation to cover one’s mouth and nose and maintain social distance in church, there were no additional restrictions concerning religious life—it turned out that more than three fifths of practitioners (62%) had attended church with the same frequency as previously during the vacation period, that is, generally several times a week. However, more than every fourth person in this group (26%) chose not to participate at all in religious practices in church. It can be assumed that these were respondents who, fearing the coronavirus, attended mass through mass media and prayed individually. The vast majority of respondents who had attended mass once a week in the pre-pandemic period returned to religious practices in church: 86% had attended church with the same frequency as usual in the month preceding the September survey. Of those who attended mass or worship less regularly (once or twice a month) in the pre-pandemic period, the majority also returned to church at an unchanged rate (75%), but 21% of the respondents in this group began practicing less often than before or not at all. In the group of respondents who said of themselves that they usually went to church a few times a year, almost half (44%) did not participate in masses or services in church after the May lifting of the limitation on the number of people in a church. Overall, 18% of Poles limited their participation in religious practices after restrictions were removed on church attendance. From a socio-demographic perspective, the share is in no way a specific group. However, there were also those (5 out of 100) who considered themselves generally non-practicing but had happened to attend mass or a service in church at least once after the lifting of the limitation on the number of people in church (Spearman’s rho = 0.822; p < 0.01, details in Table 4).

Table 4.

Habitual participation in mass and return to religious practices in church after the lifting of restrictions.

4. Discussion

The research results presented here prove that, in its initial stage, the pandemic contributed to strengthening the religiosity of some Poles, especially those who were already characterized by above-average commitment in this regard. The share of people in Poland who, under the strict government restrictions accompanying the first wave of the pandemic, did not undertake any religious activities was lower than the sum of people who were not practicing or practicing irregularly. This means that even some of the respondents who did not practice or did so occasionally before the pandemic engaged in some kind of religious practice in the initial phase of the pandemic—most often through technology. These findings are consistent with those of other studies conducted on this topic among Poles (Kowalczyk et al. 2020; Boguszewski Rafał et al. 2020). Similar observations were made by researchers in relation to the inhabitants of the United States. There, the percentage of people who previously did not identify with any religion but who participated in prayer during the outbreak of the epidemic reached 24% (Pew Research Center 2020). In the initial phase of the pandemic, a significant proportion of people sought support in faith that would help them cope with the threat they were experiencing. According to data from Google, in 95 countries (including Poland), during the pandemic, the search for the term “prayer” increased to the highest level ever recorded (Bentzen 2020a). Poles’ turn toward transcendence in a time of unusual disruption and uncertainty can also be seen in the decline in the response “I do not participate in masses, services, or religious meetings at all” in March among all Poles and in all socio-demographic groups identified in the analyses. It should be added that the March survey began just after the first officially diagnosed case of SARS-CoV-2 infection appeared in Poland (4 March) and ended shortly after the first recorded death from this illness (12 March). It is worth noting, however, that the increase in religiosity in the face of the threat posed by the pandemic is not clear, even in the initial phase. For example, research carried out in Catholic Colombia did not show such a relationship (2020).

Based on our analyses, it can be concluded that, in Poland, it is the level of religiosity before the pandemic that has determined religious engagement during the pandemic to the greatest extent. The same has been evidenced by other studies conducted in this country during the pandemic as well (Boguszewski Rafał et al. 2020). People who were more than averagely religious before the pandemic engaged in religious practice even more often during the pandemic (online or in a traditional form), even during the most severe prohibitions, and people who were previously less frequent in religious practice limited their religious activities even further during the pandemic and did not return to them after the restrictions were lifted. This applies especially to the youngest Poles (aged 18–24) and to residents of the largest urban agglomerations, that is, those groups in Poland in which we have been observing a decline in religiosity for a long time (Pew Research Center 2018; CBOS 2015). This suggests that the pandemic accelerated the process of abandoning religious practices among people whose ties to the institutional church had been loosening for some time and the thesis could be ventured that most of these people will not return to church after the pandemic. Over the course of the pandemic, as the threat became more familiar, the initial religious intensification steadily declined. In consequence, if the lifting of restrictions on community prayer in church caused any change in religious life (and in most cases it did not), the change was negative rather than positive. Therefore, in viewing the pandemic from the perspective of almost a year from its beginning (based on the data presented here, as well as cyclical—monthly—measurements), it can be concluded that this situation has contributed to an increase in the polarization of religiosity. Those Poles who previously attended church only occasionally did not return to church at all after the lifting of restrictions in the summer period, and a significant number of them will probably not go back—more as a result of atheization and secularization than of the privatization of religion.

In summary, it can be assumed that the religiosity of Poles after the pandemic will not be the same as before; the polarization, which was already visible, will intensify. Poles who had been strongly involved in religious life largely intensified their religious behavior, and people who before the pandemic very rarely or sporadically practiced their religion relinquished or further restricted their religious activity. In contrast to Western societies, where the trend is rather one-way, toward secularization, the polarization of Polish society has been observed by researchers for some time (Lisak 2015), and the pandemic will probably intensify it. This is largely due to the customary nature of Polish religiosity. It would seem that upholding tradition is too weak a motivation for practice, as is evidenced as well by the fact that some people who formerly practiced regularly did not return to Sunday mass despite the restrictions having been lifted on the number of people in churches. Such decisions were favored by the dispensation granted by the episcopate and also by simultaneous other events contributing to the decline in trust in the Polish Church (further revelations of instances of pedophilia among priests and the involvement of the clergy in the political dispute over amendment of the law on abortion). The phenomenon of the abandonment of religious practices by people who are “lukewarm” or “indifferent” to religion is currently being widely discussed in Polish journalism—both from “inside” the Church (Strzelczyk 2021; Dostatni 2021) and in the national media (Kędzierski 2020; Krzyżak 2020). The fact that people who practice consciously and reflectively are in a minority in Poland translates into the fact that the level of belief and individualist orientations have not changed. Although the initial phase of the pandemic was for some Poles an opportunity to deepen their faith, it can be seen that in the longer term, in most cases, the pandemic did not affect people’s frequency of prayer and other individual religious practices, and where the pandemic’s impact is visible, one could speak rather of a retreat from religiosity than of its intensification.

Finally, it should be added that religiosity, like other attitudes in life, does not undergo radical changes naturally, so care should be taken in interpreting people’s declarations—especially those obtained from surveys. It can be seen that at least some of the people who said they did not participate in religious practices did undertake certain individual activities in the religious field, so it can be assumed that they did not go to church out of fear for their health and will return to traditional practices after the threat has passed. At the same time, this mainly concerns those whose religiosity was deep before the pandemic. The topic definitely requires further research, including of a qualitative nature, which would allow for a better understanding of the changes and a more precise prediction of their direction, including to what extent the decline in institutional religiosity is and will be related to the privatization of religion and to what extent to secularization and atheization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B. and M.B.; methodology, R.B.; formal analysis M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B. and M.B.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, R.B. and M.B. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from CBOS and are available from https://cbos.pl/PL/home/home.php (accessed on 13 January 2021) with the permission of the director of the CBOS Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baker, Joseph O., Gerardo Martí, Ruth Braunstein, Andrew L. Whitehead, and Grace Yukich. 2020. Religion in the Age of Social Distancing: How COVID-19 Presents New Directions for Research. Sociology of Religion 81: 357–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentzen, Jeanet. 2019. Acts of God? Religiosity and natural disasters across subnational world districts. The Economic Journal 129: 2295–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bentzen, Jeanet. 2020a. In Crisis, We Pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 Pandemic. CEPR Discussion Paper DP14824. London: CEPR. [Google Scholar]

- Bentzen, Jeanet. 2020b. Rising Religiosity as a Global Response to COVID-19 Fear. Available online: VoxEU.org (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Berger, Peter. 1984. Sekularyzacja a problem wiarygodności religii. (Secularization and the problem of the credibility of religion). In Socjologia Religii. Edited by Franciszek Adamski. Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM. [Google Scholar]

- Boguszewski Rafał, Marta Makowska, Marta Bożewicz, and Monika Podkowińska. 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Religiosity in Poland. Religions 11: 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, Raphael. 2006. Religiosity and Mental Health. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 141: 1863–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bonelli, Raphael, Rachel Dew, Harold Koenig, David Rosmarin, and Sasan Vasegh. 2012. Religious and Spiritual Factors in Depression: Review and Integration of the Research. Depression Research and Treatment 2012: 962860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büssing, Arndt, Andreas Michalsen, Hans-Joachim Balzat, Ralf-Achim Grünther, Thomas Ostermann, Edmund Neugebauer, and Peter Matthiessen. 2009. Are spirituality and religiosity resources for patients with chronic pain conditions? Pain Medicine 10: 327–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- CBOS. 2015. Zmiany w zakresie podstawowych wskaźników religijności Polaków po śmierci Jana Pawła II. (Changes of Basic Indicators of Religiousness after John Paul II‘s Death). Public Opinion Research Center Research Announcement No 26. Warsaw: Public Opinion Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- CBOS. 2020a. Wpływ pandemii na religijność Polaków. (Impact of Coronavirus Pandemic on Religiousness of Poles). Public Opinion Research Center Research Announcement No 74. Warsaw: Public Opinion Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- CBOS. 2020b. Religijność Polaków w warunkach pandemii. (Religiousness of Poles During a Pandemic). Public Opinion Research Center Research Announcement No 137. Warsaw: Public Opinion Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- CBOS. 2020c. Postawy wobec epidemii koronawirusa na przełomie maja i czerwca. (Attitudes toward Coronavirus Epidemic at the Turn of May and June). Public Opinion Research Center Research Announcement No 73. Warsaw: Public Opinion Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- CBOS. 2020d. Current Problems and Events. Survey No 356. for internal use. Warsaw: Public Opinion Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- CBOS. 2020e. Religijność Polaków w ostatnich 20 latach. (Religiousness of Poles in the Last 20 Years). Public Opinion Research Center Research Announcement No 63. Warsaw: Public Opinion Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Dostatni, Tomasz. 2021. Po pandemii w Kościele nie będzie dużej części młodego pokolenia. (After the pandemic, there will not be a large part of the younger generation in the Church). Więź, January 11. Available online: https://wiez.pl/2021/01/11/o-dostatni-po-pandemii-w-kosciele-nie-bedzie-duzej-czesci-mlodego-pokolenia/(accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Durkheim, Emile. 1898. De la définition des phénomènes religieux. L’Année Sociologique II: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojsgaard, Morten, and Margit Warburg. 2005. Religion and Cyberspace. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Höllinger, Franz, and Johanna Muckenhuber. 2019. Religiousness and existential insecurity: A cross-national comparative analysis on the macro-and micro-level. International Sociology 34: 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immerzeel, Tim, and Frank van Tubergen. 2011. Religion as reassurance? Testing the insecurity theory in 26 European countries. European Sociological Review 29: 359–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahana, Eva, Boaz Kahana, Zew Harel, and Toma Rosner. 1988. Coping with extreme trauma. In Human Adaptation to Extreme Stress. Edited by John P. Wilson, Zev Harel and Boaz Kahana. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kędzierski, Marcin. 2020. Przemija bowiem postać tego świata. LGBT, Ordo Iuris i rozpad katolickiego imaginarium (The form of this world is passing away. LGBT, Ordo Iuris and the collapse of the Catholic imaginary). Klub Jagielloński, August 8. Available online: https://klubjagiellonski.pl/2020/08/08/przemija-bowiem-postac-tego-swiata-lgbt-ordo-iuris-i-rozpad-katolickiego-imaginarium/(accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Koenig, Harold, James Kvale, and Carolyn Ferrel. 1988. Religion and well-being in later life. Gerontologist 28: 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczyk, Oliwia, Krzysztof Roszkowski, Xavier Montane, Wojciech Pawliszak, Bartosz Tylkowski, and Anna Bajek. 2020. Religion and Faith Perception in a Pandemic of COVID-19. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2671–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzyżak, Tomasz. 2020. Sondaż: Kościół w błyskawicznym tempie traci wiernych. (Poll: The Church Is Losing Its Faithful at a Rapid Pace) Rzeczpospolita. 15 November 2020. Available online: https://www.rp.pl/Kosciol/311159945-Sondaz-Kosciol-w-blyskawicznym-tempie-traci-wiernych.html (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Lisak, Marcin. 2015. Transformacje religijności Polaków—wybrane aspekty religijnej zmiany. (Transformations of Poles’ religiosity—selected aspects of religious change). Sympozjum 2: 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchetti, Giancarlo, Leonardo Garcia Góes, Stefani Garbulio Amaral, Gabriela Terzian Ganadjian, Isabelle Andrade, Paulo Othávio de Araújo Almeida, Victor Mendes do Carmo, Gonzalez Manso, and Maria Elisa. 2020. Spirituality, religiosity and the mental health consequences of social isolation during COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luckmann, Thomas. 1967. The Invisible Religion: The Problem of Religion in Modern Society. New York: MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdanian, Artin. 2018. Religion and Depression: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health Forecast 1: 1003. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, Bronisław. 1990. Mit, magia, religia. (Myth, Magic, Religion.), Dzieła. t. 7. Warszawa: Wyd. Naukowe PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Mariański, Janusz. 2007. Nowe wymiary zróżnicowania religijności w Polsce. (New Dimensions of Religious Diversity in Poland). In Jedna Polska? Dawne i nowe zróżnicowania społeczne (One Poland? Old and New Social Differences). Edited by Andrzej Kojder. Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM. [Google Scholar]

- Mariański, Janusz. 2018. Kościół katolicki w Polsce w kontekście społecznym. Studium socjologiczne. (The Catholic Church in Poland in the Social Context. Sociological Study). Warszawa: Wyd. Naukowe PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Meza, Diego. 2020. In a Pandemic Are We More Religious? Traditional Practices of Catholics and the COVID-19 in Southwestern Colombia. International Journal of Latin American Religions 4: 218–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health (Ministerstwo Zdrowia). 2020. Rozporządzenie Ministra Zdrowia z dnia 13 marca 2020 r. w sprawie ogłoszenia na obszarze Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej stanu zagrożenia epidemicznego. (Regulation of the Minister of Health of 13 March 2020 on the Declaration of an Epidemic Threat in the Territory of the Republic of Poland). Available online: sejm.gov.pl (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Moberg, David. 2008. Spirituality and aging: Research and implications. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging 20: 95–134. [Google Scholar]

- Molteni, Francesco. 2020. A Need for Religion: Insecurity and Religiosity in the Contemporary World. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Molteni, Francesco, Riccardo Ladini, Ferruccio Biolcati, Antonio M. Chiesi, Dotti Sani, Giulia Maria, Simona Guglielmi, Marco Maraffi, Andrea Pedrazzani, Paolo Segatti, and et al. 2020. Searching for comfort in religion: Insecurity and religious behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. European Societies 23: 704–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2011. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Cheonghwan, and Kyungrae Kim. 2021. COVID-19 and Korean Buddhism: Assessing the Impact of South Korea’s Coronavirus Epidemic on the Future of Its Buddhist Community. Religions 12: 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2018. The Age Gap in Religion around the World. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/12/05/how-do-european-countries-differ-in-religious-commitment/?fbclid=IwAR104AMVTtqg55hhbpG3ofp_fM3Iu0lKymZjU1vrPNac3v-Ov5z__VlV3sw (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Pew Research Center. 2020. Most Americans Say Coronavirus Outbreak Has Impacted Their Lives. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/03/30/most-americans-say-coronavirus-outbreak-has-impacted-their-lives/ (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Sroczyńska, Maria. 2018. O potrzebie religii w ponowoczesnym świecie (refleksje socjologa). (On the need of religion in the postmodern world. Reflections of a sociologist). Chrześcijaństwo, Świat, Polityka 22: 16–175. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelczyk, Grzegorz. 2021. Dejcie pozór! (Watch out!) W drodze 1/2021: 18–19. Available online: https://wdrodze.pl/article/dejcie-pozor/ (accessed on 18 January 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).