The Animated Temple and Its Agency in the Urban Life of the City in Ancient Mesopotamia Beate Pongratz-Leisten, NYU, ISAW

Abstract

:- Be forgiving to your city, Babylon,

- Grant mercy to your temple, Esagila,

- With your exalted word, lord of the great gods,

- May light be set (again) before the citizens of Babylon.

1. The Temple as Mirror of Domestic Life

2. Temple and Urban Communities

as well as in the name iri-ku3ki or “sacred city” for the temple of the goddess Bau in Girsu (Selz 1995, pp. 5–6, 122, 237; cited by Löhnert 2013, p. 265).(ll. 14–18) House Keš platform of the Land, important fierce bull! Growing as high as the hills, embracing the heavens, growing as high as Ekur, lifting its head among the mountains! Rooted in the Apsu, verdant like the mountains! Will anyone else bring forth something as great as Keš? … (59–73) It is indeed a city, it is indeed a city! Who knows its interior? The house Keš is indeed a city!(After Wilcke 2006, p. 221)

3. Conflation of Temple, Divinity, and Community as Translated into the Temple’s Agency

507−513O Ulmash, upper land, … of the Land, terrifying lion battering a wild bull, net spreading over an enemy, making silence fall upon a rebel land on which, as long as it remains insubmissive, spittle is poured! House of Inana of silver and lapis lazuli, a storehouse built of gold, your princess is an urabu bird, the Mistress of the Nigin-jar.514−518Arrayed in battle, jubilantly (?) beautiful, ready with the seven maces, washing her tools for battle, opening the door of battle and …, the extremely wise one of heaven, Inana, has erected a house in your precinct, O house Ulmash, and taken her seat upon your dais.51912 lines: the house of Inana in Ulmash.

4. The Temple and Its Performance in Jurisdiction

- Iddin-Dagan A 169–171

- In the palace (é.gal, “House, Advice for the Land of Sumer,” neck-stock of the land, “House of the River

- Ordeal,” a dais is set up for Ninegal.17

5. The Temple’s Agency Anchored in the Times of Yore

- When An/Anu, Enlil, and Enki/Ea created heaven and earth,

- Had their sanctuary built in the country to soothe their heart,

- Had built their palaces and taken abode (in them),

- Had [imposed?)] the carrying basket upon the black-headed people,

- They appointed the shepherd (the king) in the country, who provides for the sanctu aries of the gods.

- The great gods joyfully entered the Ubšukinna and

- Ordained his destiny in a superb way, they [assigned to him(?)] (the ability)

- To make decision(s).

(ii 9–20) Through the sagacity of Ea, through the intelligence of Marduk, through the wisdom of Nabû and Nissaba, by means of the vast mind with which the god who created me endowed (me), I deliberated in my great wisdom and I commissioned skilled experts, and the surveyor measured the dimensions with the twelve-cubit rule. (ii 21–30) The master builders stretched the measuring cords, they established the outlines. I inquired through extispicy by consulting Šamaš, Adad, and Marduk and, where my mind deliberated (and) I pondered (unsure of) the dimensions, the great gods revealed (the truth) to me by the procedure of (oracular) confirmation.

- When the god Anu created heaven,

- (when) the god Nudimmud (=Ea) created the apsû, his dwelling,

- the god Ea pinched off a piece of clay in the apsû,

- created Kulla (brick god) for the restoration of [temples],

- created the reed marsh and the forest for the work of their construction,

- created the gods Ninildu (carpentry), Ninsimug (god of metal workers), and Arazu (god of prayer)

- to be the completers of their construction work,

- created mountains and oceans for everything …,

- created the deities Gushkinbanda (god of goldsmiths), Ninagal (god of metalworkers), Ninzadim (god

- of engravers), and Ninkurra (goddess of stonecutters) for their work,

- (created) the abundant products (of mountain and ocean) to be offerings ….,

- created the deities Ashnan (grain goddess), Lahar (cattle god), Siris (wine goddess), Ningizzida (god of

- vegetation), Ninsar (vegetation goddess) …

- for making their revenues abundant …

- created the deities Umunmutamku (Marduk’s cook) and Umunmutamnag (Marduk’s cupbearer)

- to be presenters of offerings,

- created the god Kusig, high-priest of the great gods,

- to be the one who completes their rites and ceremonies.

- Created the king to be the provider …

- Created men to be the makers.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | I would like to thank Michael Roaf for his thoughtful comments on this article. Further thanks go to Irina Oryshkevich for her editorial work. |

| 2 | See below. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | Very few divine statues survive since these were made out of precious materials that had to be imported to Mesopotamia, which was poor in natural resources. |

| 5 | The most prominent ones are TINTIRki, which encompass the temples of Babylon, the Assur Directory, and the Nippur Compendium, all published together with other texts of the same genre in (George 1992). |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Sallaberger reads AB as “place” in a more general sense as in ud.gal.nun orthography AB/UNUG corresponds to ki “place.” His argument that because the office of the sanga, generally considered an administrator of the temple, is also associated with the é-gal in Lagash, AB should be interpreted as a profane institution, is unconvincing as the administrative complex of the queen in Lagash is dedicated to the goddess Bau, and so our modern distinction between sacred and profane does not apply here. Wang assumes that early on Nippur was written as EN.KID in the Archaic City Seal designating the toponym /nibru/ and was only later read as /ellil/; (Wang 2011, pp. 41–59, 218–19). |

| 8 | RIME 2, E2.1.4.10: 5-57: “When the Four Quarters (of the World) together revolted against him, through the love Ishtar showed to him, he was victorious in nine battles in (only) one year, and he captured the kings who had risen against him. In view of the fact that he protected the foundations of his city from danger, (the citizens of) his city requested from Ishtar in Eanna (in Uruk), Enlil in Nippur, Dagan in Tuttul, Ninhursag in Kesh, Ea in Eridu, Sin in Ur, Shamash in Sippar, (and) from Nergal in Kutha that he be (made) the god of their city, and they built a temple for him in the midst of Akkade.” |

| 9 | For a summary of the various Sumerian City Laments, see (Tinney 1996, pp. 19–25). |

| 10 | Ishme-Dagan W ll. 1–13. (Ludwig 1990, pp. 93–160 and ETCSL 2.5.4.23): “City whose terrifying splendor (melem4) extends over heaven and earth, whose towers are exceptionally grand, shrine (èš) Nippur! Your power reaches to the edges of the uttermost extent of heaven and earth. Of all the brick buildings erected in the Land, your brickwork is the most excellent. You have allowed all the foreign lands and as many cities as are built to receive excellent divine powers” (my translation). |

| 11 | As Michael Roaf reminds me that also applied to the lightning that struck Durham cathedral which was attributed God taking action against the alleged atheism of the bishop. Similar explanations were given for the burning of Notre Dame. |

| 12 | SAA 10 no. 112. |

| 13 | LKA no. 126 = BAM no. 341, Maul (1994, p. 555). |

| 14 | See the passage in Gudea’s building hymn in (Edzard 1997, CylA xxiv 18–19). |

| 15 | The Akkadian text suggests that there was a stele and image, possibly in the form of a statue or a relief; the upper part of the stele, however, contains an image of the king before the sun god, so the text may refer to this combination of text and image on the stele. |

| 16 | For a discussion of these two alternative possibilities, see (Pongratz-Leisten, forthcoming a). The stele of Adad-nirari III in the temple of Tell Rimah in Syria exemplifies the latter possibility. |

| 17 | After Claus Wilcke in Janowski and Schwemer (2013, p. 669): “Im Palast, dem Hause >Weisung für das Land Sumer<, dem Zwingstock (aller Fremdländer, im >Hause Ordalfluss<, errichteten die Schwarzköpfigen, das Volk, nachdem es sich versammelt hatte, der Herrin des Palastes einen Hochsitz.”; for a different translation see ETCSL 2.5.3.1 Iddin-Dagan A: “When the black-headed people have assembled in the palace, the house that advises the Land, the neck-stock of all the foreign countries, the house of the river ordeal, a dais is set up for Ninegala.” |

| 18 | |

| 19 | Enki’s Journey to Nippur, ETCSL 1.1.4: 14 šeg12-bi inim dug4-dug4 ad-gi4-gi4. |

| 20 | (Roth 1997, 2nd ed., 135, xlviii 39–58): “May the protective spirits, the gods who enter the Esagil temple, and the very brickwork of the Esagil temple make my daily portents auspicious before the gods Marduk, my lord, and Zarpanitu, my lady, šēdum lamassum ilū ēribūt Esagil libitti Esagil igirrê ūmišam ina mahar Maduk bēlija Zarpanītum bēltija lidammiqū. |

| 21 | See the treaty between Tudhaliya IV and Kurunta of Tarhuntašša (Kitchen and Lawrence 2012, no. 73, iv 44–51): “Now, this tablet has been prepared as the 7th copy, and with the seal of the Sun-goddess of Arinna, and with the seal of the Storm-god of Hatti has it been sealed. Thus, one tablet (deposited) before the Sun-goddess of Arinna; one tablet before the Storm-god of Hatti; one tablet before Lelwani; one tablet before Hepat of Kizzuwatna; one tablet before the Storm-god of lightning(?); one tablet in the Royal Palace, deposited before Zitkhariyas; and one Tablet, Kurunta, King of the land of Tarhuntassa, keeps in his house.” |

| 22 | A similar notion of giš-hur comes up in the Sun God Tablet of Nabû-apla-iddina, where the term is used for the archetypal image of the god (Woods 2004, iii 19–31); see also my discussion in Pongratz-Leisten (forthcoming c). |

| 23 | And even for the present, see https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3747166/Worshippers-remote-Bolivian-chapel-declare-miracle-statue-Virgin-Mary-begins-bleeding-eyes.html (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 24 |

References

- Ambos, Claus. 2010. Building Rituals from the First Millennium BC. In From the Foundations to the Crenellations. Essays on temple Building in the Ancient Near East and Hebrew Bible. Edited by Mark J. Bod and Jamie Novotny. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, pp. 221–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrani, Zainab. 2008. Rituals of War. The Body and Violence in Mesopotamia. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Jeremy A., Graham Cunninhgham, Jarle Ebeling, Esther Flückiger-Hawker, Eleanor Robson, Jon Taylor, and Gabor Zólyom. 1998–2006. The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian (ETCSL), Literature. Oxford. Available online: http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. 2013. The Sacrality of Things: An Inquiry into Divine Materiality in the Christian Middle Ages. Irish Theological Quarterly 78: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. 2015. The Animation and Agency of Holy Food. In The Materiality of Divine Agency. Edited by Beate Pongratz-Leisten and Karen Sonik. Boston and Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 70–85. [Google Scholar]

- Caplice, R. 1970. Namburbi Texts in the British Museum IV. Orientalia 39: 111–51. [Google Scholar]

- Da Riva, Rocio. 2013. The Inscriptions of Nabopolassar, Amēl-Marduk and Neriglissar. Boston and Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Doquang, Mailan S. 2018. The Lithic Garden: Nature and the Transformation of the Medieval Church. Oxford and New Yrok: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Droogan, Julian. 2012. Religion, Material Culture and Archaeology. London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Edzard, Dietz Otto. 1997. Gudea and His Dynasty. Toronto, Buffalo and London: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Englund, Robert K., and Hans J. Nissen. 1993. Die lexikalischen Listen der archaischen Texte aus Uruk. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. [Google Scholar]

- Fales, F. Mario. 2013. The Temple and the Land. In Tempel im Alten Orient. Colloquien der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft. Edited by Kai Kaniuth, Anne Löhnert, Jared L. Miller, Adelheid Otto, Michael Roaf and Walther Sallaberger. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, vol. 7, pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Frame, Grant. 2021. The Royal Inscriptions of Sargon II, King of Assyria (721–705 BC). RINAP 2. University Park: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- George, Andrew. 1992. Babylonian Topographical Texts. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- George, Andrew. 1993. House Most High. The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

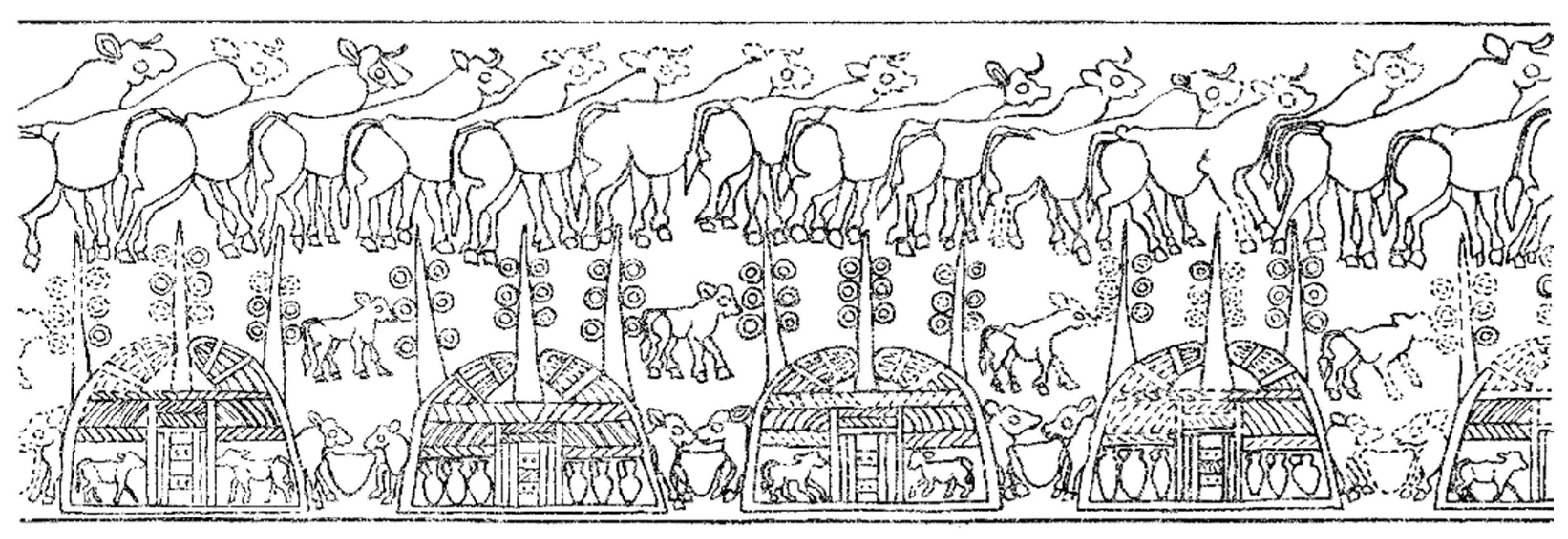

- Hamilton, R. W. 1967. A Sumerian Cylinder Seal with Handle in the Ashmolean Museum. Iraq 29: 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Timothy P., and James F. Osborne. 2012. Building XVI and the Neo-Assyrian Sacred Precinct at Tell Tayinat. Journal of Cuneiform Studies 64: 124–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, Ian. 2012. Entangled. An Archaeology of the Relationships between Humans and Things. Malden and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Janowski, Bernd, and Daniel Schwemer, eds. 2013. Texte aus der Umwelt des Alten Testaments, Neue Folge, Band 7. Hymnen, Klagelieder und Gebete. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen, Kenneth A., and Paul J. N. Lawrence. 2012. Treaty, Law and Covenant in the Ancient Near East. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Lauinger, Jacob. 2012. Esarhaddon’s Succession Treaty at Tell Tayinat: Text and Commentary. Journal Cuneiform Studies 64: 87–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichty, Erle. 2011. The Royal Inscriptions of Esarhaddon, King of Assyria (680-669 BC). RINAP 4. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Linssen, Marc J. H. 2004. The Cults of Uruk and Babylon. The Temple Ritual Texts as Evidence for Hellenistic Cult Practices. Leiden and Boston: Styx. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, Alasdair. 1989. Court Poetry and Literary Miscellanea. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, Alasdair. 2013. Hemerologies of Assyrian and Babylonian Scholars. Cornell University Studies in Assyriology and Sumerology (CUSAS). Bethesda: CDL Press, vol. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Löhnert, Anne. 2013. Das Bild des Tempels in der sumerischen Literatur. In Tempel im Alten Orient. Colloquien der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft. Edited by Kai Kaniuth, Anne Löhnert, Jared L. Miller, Adelheid Otto, Michael Roaf and Walther Sallaberger. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, vol. 7, pp. 263–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, Marie-Christine. 1990. Untersuchungen zu den Hymnen Išme-Dagans von Isin. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, J. R. 1993. Cities, Seals and Writing: Archaic Seal Impressions from Jemdet Nasr and Ur. Materialien zu den Frühen Schriftzeugnissen des Vorderen Orients (MSVO). Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Maul, Stefan M. 1994. Zukunftsbewältigung. Eine Untersuchung altorientalischen Denkens anhand der babylonisch-assyrischen Löserituale (Namburbi). Mainz: Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, Werner R. 1978. Seleukidische Rituale aus Warka mit Emesal-Gebeten. Orientalia 47: 431–58. [Google Scholar]

- Meinhold, Wiebke. 2013. Tempel, Kult und Mythos: Zum Verhältnis von Haupt- und Nebengottheiten in Heiligtümern der Stadt Aššur. In Tempel im Alten Orient. Colloquien der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft. Edited by Kai Kaniuth, Anne Löhnert, Jared E. Miller, Adelheid Otto, Michael Roaf and Walther Sallaberger. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, vol. 7, pp. 325–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pongratz-Leisten, Beate, and Karen Sonik, eds. 2015. The Materiality of Divine Agency. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Pongratz-Leisten, Beate. Forthcoming a. The Aura of the Illegible: A Multimodal Approach to Writing. In Klänge der Archäologie—Festschrift für Ricardo Eichmann. Edited by C. Bührig, M. van Ess, I. Gerlach, A. Hausleiter and B. Müller-Neuhof. In press.

- Pongratz-Leisten, Beate. Forthcoming b. The Sociomorphic Structure of the Polytheistic Pantheon in Mesopotamia and its Meaning for Divine Agency and Mentalization. In “A Community of Peoples.” Studies on Society and Politics in the Bible and Ancient Near East in Honor of Daniel E. Fleming. Leiden: Brill.

- Pongratz-Leisten, Beate. Forthcoming c. Conceptualizing Divinity Between Cult and Theology in the Ancient Near East. In Dieux, rois et capitales dans le Proche-Orient ancien. Compte rendu de la LXVe Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale (Paris, 8–12 juillet 2019). Edited by Marine Béranger, Francesca Nebiolo and Nele Ziegler. PIPOAC 5. Leuven: Peeters.

- Porada, Edith. 1993. Why Cylinder Seals? Engraved Cylinder Seals of the Ancient Near East, Fourth to First Millennium B.C. The Art Bulletin 75: 563–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postgate, J. Nicholas. 1992. Early Mesopotamia. Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

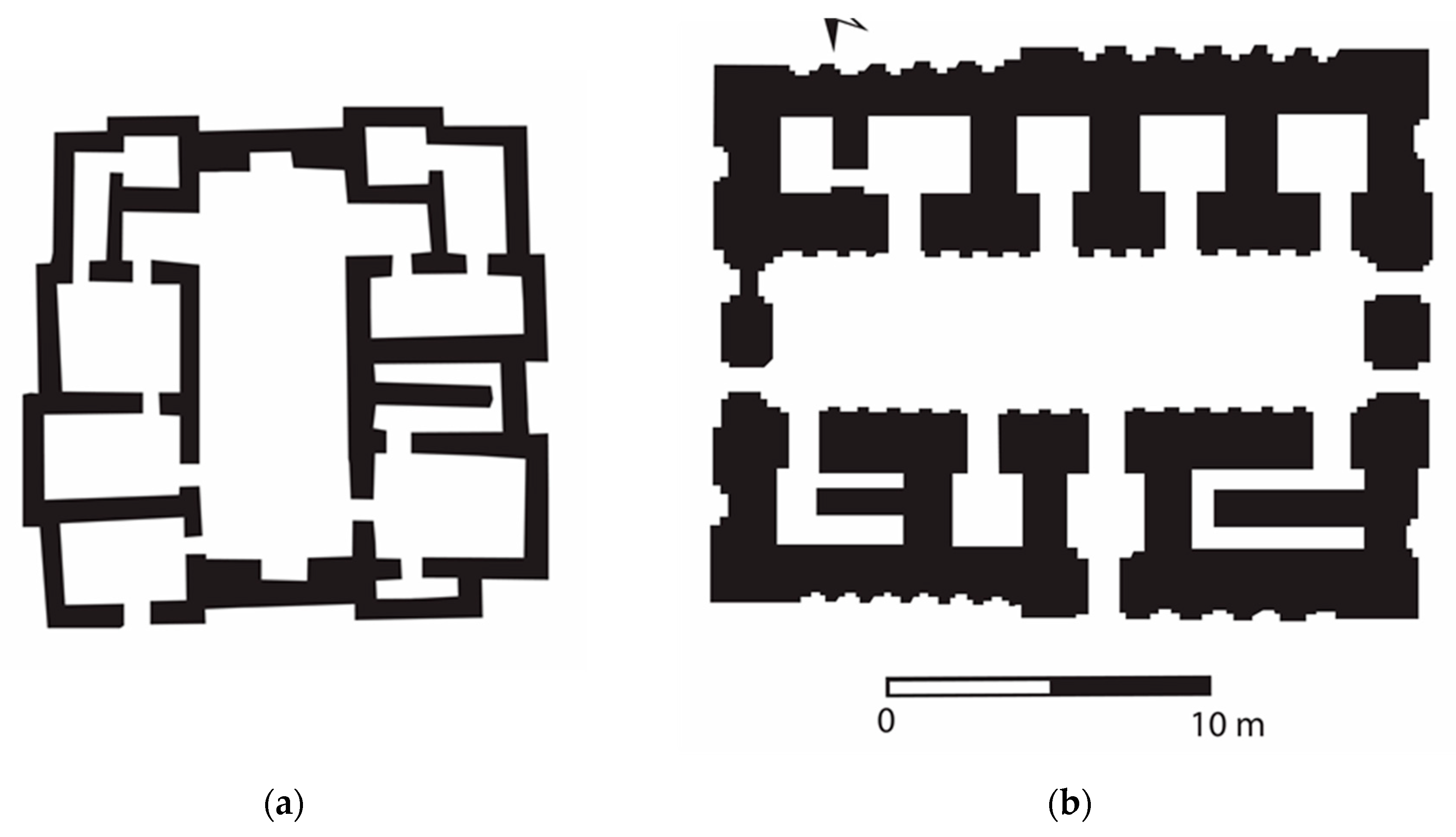

- Roaf, Michael. 1995. Palaces and Temples in Ancient Mesopotamia. In Civilizations of the Ancient Near East. Edited by Jack M. Sasson. New York: Scribner’s, vol. 1, pp. 423–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rochberg, Francesca. 2009. ‘The Stars Their Likeness.’ Perspectives on the Relation Between Celestial Bodies and Gods in Ancient Mesopotamia. Anthropomorphic and Non-Anthropomorphic Aspects of Deity in Ancient Mesopotamia. Edited by Barbara Nevling Porter. Transactions of the Casco Bay Assyriological Institute. Winona Lake: Casco Bay Assyriological Institute, pp. 41–91. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Martha. 1997. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. Atlanta: Scholars Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sallaberger, Walther. 2010. The City and the Palace at Archaic Ur. In Shepherds of the Black-Headed People: The Royal Office Vis-À-Vis Godhead in Ancient Mesopotamia. Edited by K. Šašková, L. Pecha and P. Charvát. Plzeň: Západočeská universita v Plzni, pp. 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Selz, Gebhard. 1995. Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt des Altsumerischen Stadtstaates von Lagaš. Occasional Publications of the Samuel Noah Kramer Fund, 13. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöberg, Åke W., and E. Bergmann S. J. 1969. The Collection of the Sumerian Temple Hymns. New York: J. J. Augustin Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Steinkeller, Piotr. 2002. Archaic City Seals and the Question of Early Babylonian Unity. In Riches Hidden in Secret Places, ANE Studies in Memory of Thorkild Jacobsen. Edited by T. Abusch. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 249–57. [Google Scholar]

- Szarzynska, Krystyna. 1993. Offerings for the Goddess Inanna in Archaic Uruk. Revue d’Assyriologie 87: 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tinney, Steve. 1996. The Nippur Lament. Royal Rhetoric and Divine Legitimation in the Reign of Išme-Dagan of Isin (1953–1935 B.C.). Philadelphia: Samual Noah Kramer Fund, University of Pennsylvania Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Villard, Pierre. 2019. L’Ezida de Kalhu et son clergé au VIIe siècle av. J.-C. d’après la documentation textuelle. In Ina Dmarri u qan Ṭuppi. Par la Bêche et le Stylet. Cultures et Sociétés Syro-Mésopotamiennes. Mélanges offertes à Olivier Rouault. Edited by Philippe Abrahami and Laura Battini. Archaeopress Ancient Near Eastern Archaeology 5. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- von Soden, Wolfram. 1975. Le temple: Terminologie lexicale. Einleitung zum Colloqium am 6. Juli 1972. In Le temple et le culte. Compte rendue de la vingtième Rencontre Assyyriologique Internationale organisée à Leiden du 3 au 7 juillet 1972 sous les auspices du Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. PIHANS 37. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, pp. 133–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xianhua. 2011. The Metamorphosis of Enlil in Early Mesopotamia. Münster: Ugarit Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcke, Claus. 2006. Die Hymne auf das Heiligtum Keš. Zur Struktur und ‘Gattung’ einer altsumerischen Dichtung und zu ihrer Literaturtheorie. In Approaches to Sumerian Literature. Studies in Honour of Stip (H.L.J. Vanstiphout). Edited by Piotr Michalowski and Niek Veldhuis. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 201–37. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, Irene J. 2000. Babylonian Archaeologists of the(ir) Mesopotamian Past. Paper presented at the First International Congress of the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Rome, Italy, 18–23 May 1998; Edited by P. Matthiae, A. Enea, L. Peyronel and F. Pinnock. Rome: La Sapienza, pp. 1787–800. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, Irene J. 2007. Agency Marked, Agency Ascribed: The Affective Object in Ancient Mesopotamia. In Art’s Agency and Art History. Malden and Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 42–69. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, Irene J. 2010. Seat of Kingship"/A Wonder to Behold. In On Art in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Irene Winter. Leiden and Boston: Brill, vol. 2, pp. 333–75. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, Christopher. 2004. The Sun-God Tablet of Nabû-apla-iddina Revisited. Journal of Cuneiform Studies 56: 23–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, Nicolas. 2001. Space and Time in the Religious Life of the Near East. Sheffield: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Masamichi. 1994. The Dynastic Seal and Ninurta’s Seal: Preliminary Remarks on Sealing by the Local Authorities of Emar. Iraq 56: 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pongratz-Leisten, B. The Animated Temple and Its Agency in the Urban Life of the City in Ancient Mesopotamia Beate Pongratz-Leisten, NYU, ISAW. Religions 2021, 12, 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080638

Pongratz-Leisten B. The Animated Temple and Its Agency in the Urban Life of the City in Ancient Mesopotamia Beate Pongratz-Leisten, NYU, ISAW. Religions. 2021; 12(8):638. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080638

Chicago/Turabian StylePongratz-Leisten, Beate. 2021. "The Animated Temple and Its Agency in the Urban Life of the City in Ancient Mesopotamia Beate Pongratz-Leisten, NYU, ISAW" Religions 12, no. 8: 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080638

APA StylePongratz-Leisten, B. (2021). The Animated Temple and Its Agency in the Urban Life of the City in Ancient Mesopotamia Beate Pongratz-Leisten, NYU, ISAW. Religions, 12(8), 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080638