Not Seeing Is Believing: Ritual Practice and Architecture at Chalcolithic Çadır Höyük in Anatolia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

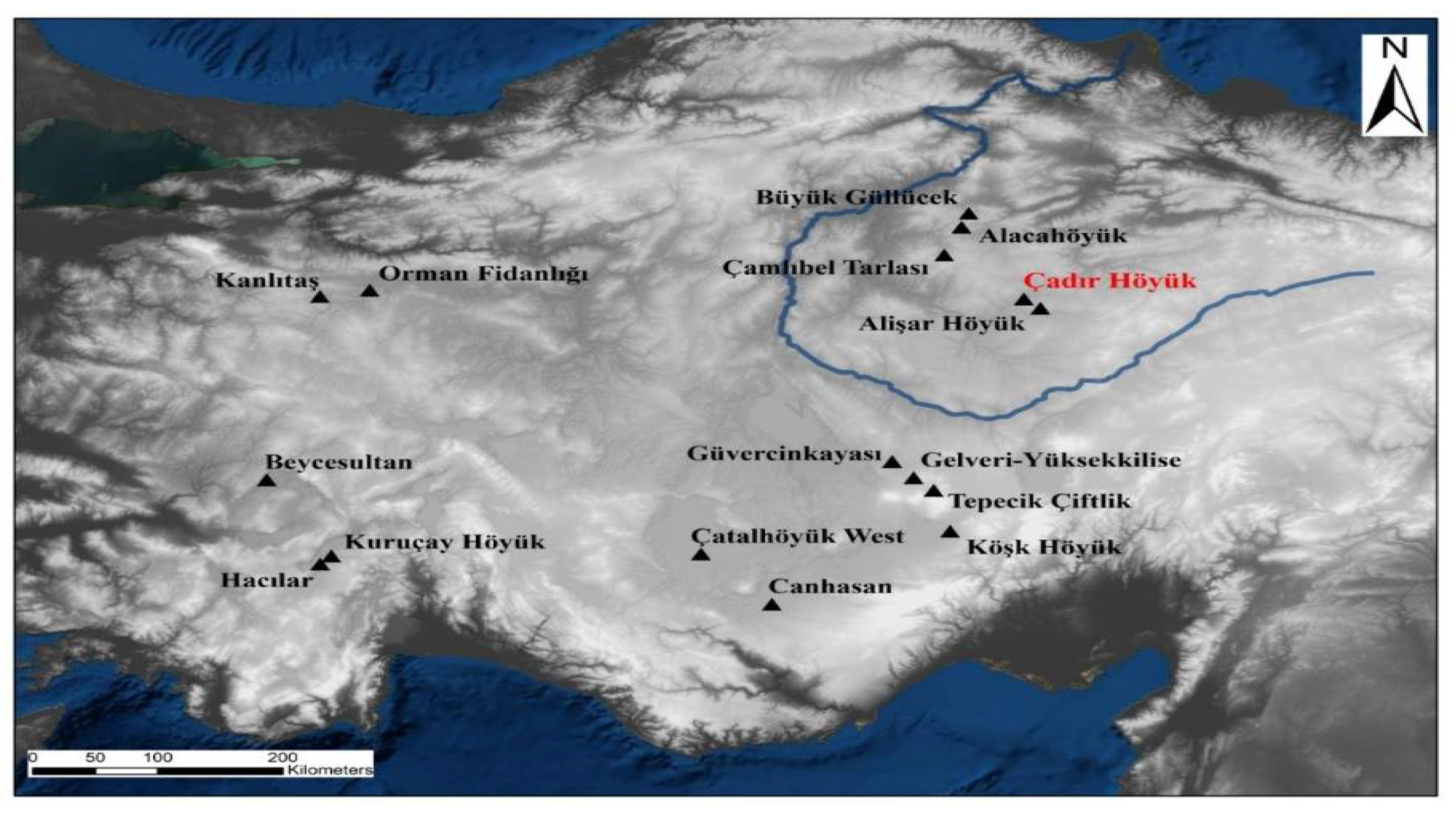

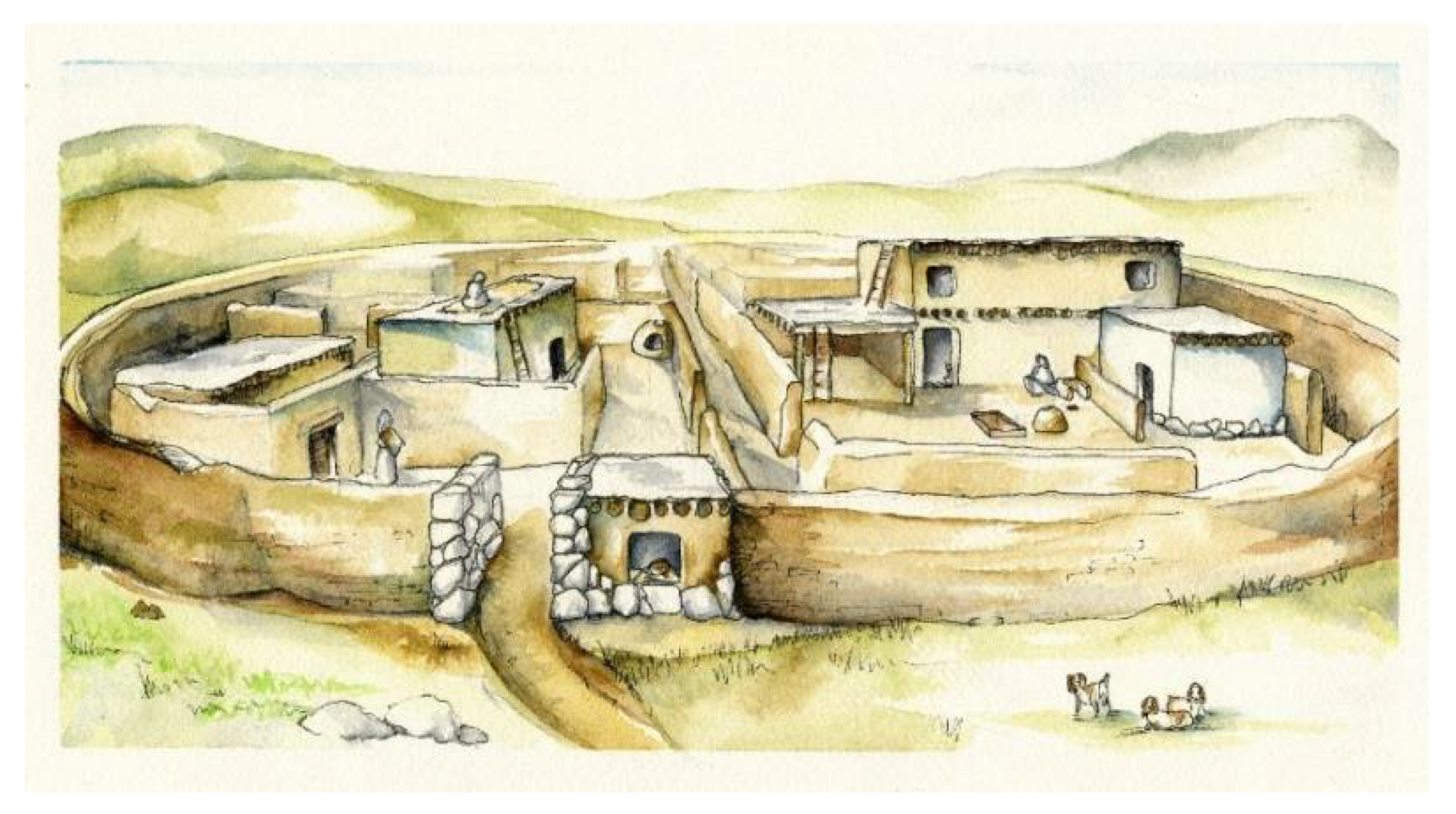

2. The Late Chalcolithic Lower Town at Çadır Höyük

3. Sacred Spaces in the Chalcolithic: Making, Seeing, and Destroying

3.1. Making

3.2. Seeing

3.3. Destroying

4. Changing Contexts and Stable Practice at Çadır Höyük

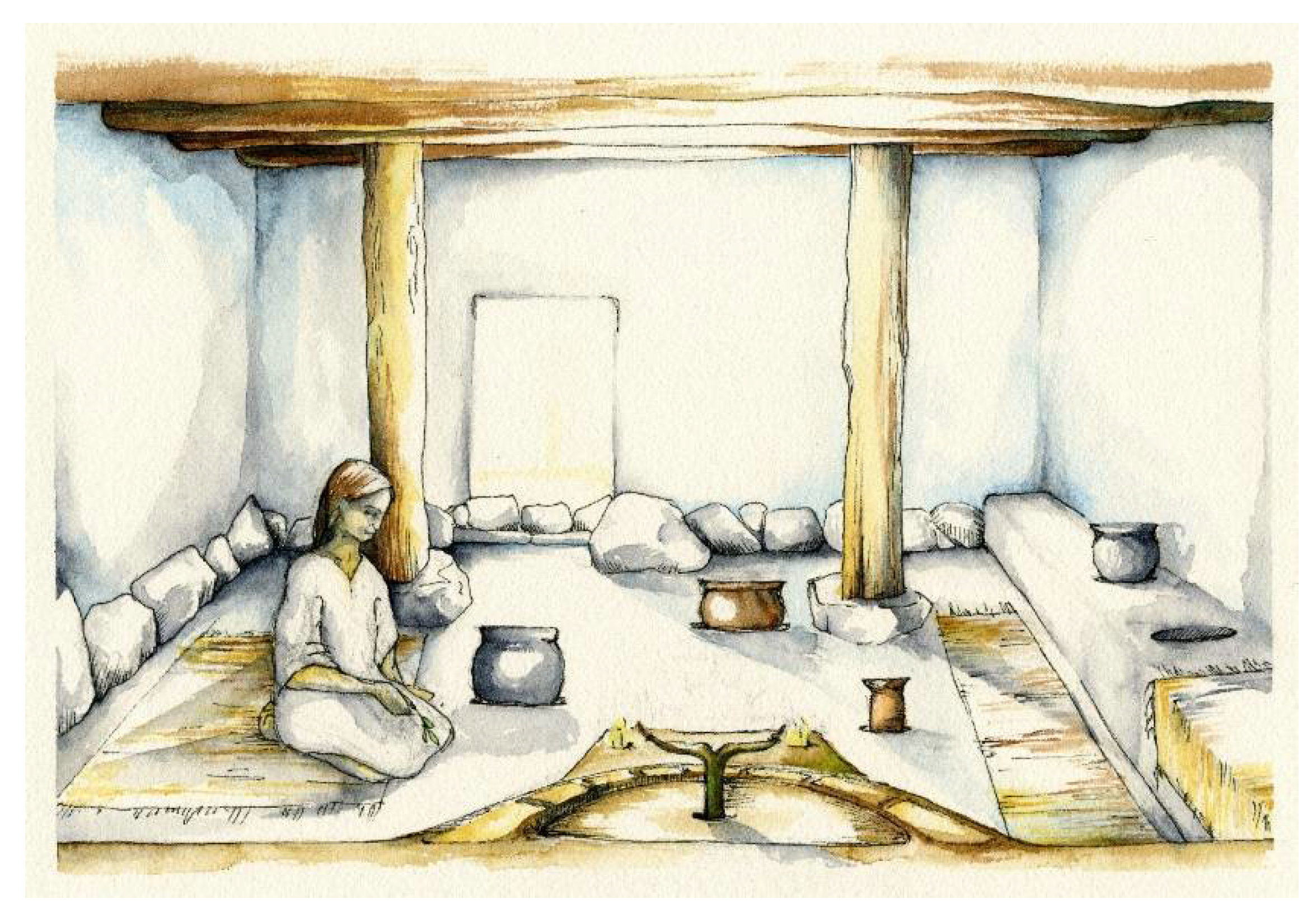

4.1. Domestic Compounds and Household Ritual: The Agglutinated Phase (ca. 3800–3600 BCE)

4.2. House Killing and the Repurposing of Domestic Space: The Burnt House Transition and Pre-Omphalos Phase

4.3. Changing Economies, Changing Rituals: The Burnt House and Omphalos Building Phases (ca. 3600–3200 BCE)

5. Demolition and Abandonment

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Algaze, Guillermo. 1993. The Uruk World System. The Dynamics of Expansion of Early Mesopotamian Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Atakuman, Çiğdem. 2015. From Monuments to Miniatures: Emergence of Stamps and Related Image-Bearing Objects during the Neolithic. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 24: 759–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelard, Gaston. 1958. The Poetics of Space. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Douglas. 2018. Breaking the Surface: An Art/Archaeology of Prehistoric Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, Douglas, Denise Carruthers, Andrew Fairbairn, and Jessica Pearson. 2011. Ritual in the Landscape: Evidence from Pınarbaşı in the Seventh-Millennium Cal BC Konya Plain. Antiquity 85: 380–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, Douglas, Andrew Fairbairn, and Louise Martin. 2017. The Animate House: The Institutionalization of the Household in Neolithic Central Anatolia. World Archaeology 49: 753–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banning, Edward B. 2011. So Fair a House: Gobekli Tepe and the Identification of Temples in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of the Near East. Current Anthropology 52: 619–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosiewicz, László. 2000. Cattle Offering from the Temple of Montuhotep, Sankhkara (Thebes, Egypt). In Archaeozoology of the Near East IVB, Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on the Archaeozoology of Southwestern Asia and Adjacent Areas. Edited by M. Mashkour, A. M. Choyke, H. Buitenhjuis and F. Poplin. Groningen: Center for Archeological Research and Consultancy, pp. 164–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, Jan-Dryzysztof, and Gülçin İlgezdi Bertram. 2021. The Late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age in Central Anatolia: Introduction–Research History–Chronological Concepts–Sites, Their Characteristics and Stratigraphies. Istanbul: Arkeolojo ve Sanat Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Bird-David, Nurit. 1999. “Animism” Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology (with comments). Current Anthropology 40: 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonogofsky, Michelle. 2003. Neolithic Plastered Skulls and Railroading Epistemologies. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 331: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brück, Joanna. 1999. Ritual and Rationality: Some Problems of Interpretation in European Archaeology. European Journal of Archaeology 2: 313–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Heather, Susan Arthure, and Cherrie de Leiuen. 2016. A Context for Concealment: The Historical Archaeology of Folk Ritual and Superstition in Australia. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 2: 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Tristan, Scott Haddow, Nerissa Russell, Amy Bogaard, and Christina Tsoraki. 2015. Laying the Foundations: Creating Households at Neolithic Çatalhöyük. In Assembling Çatalhöyük. Edited by Ian Hodder and Arkadiusz Marciniak. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, pp. 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Cassis, Marica, and Anthony Lauricella. 2021. Positive Abandonment: The Case for Çadır Höyük. In Deserted Villages: Perspectives from the Eastern Mediterranean. Edited by Rebecca Seifried and Deborah B. Stewart. Grand Forks: University of North Dakota Digital Press, pp. 27–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cassis, Marica, and Sharon R. Steadman. 2014. Çadır Höyük: Continuity and Change on the Anatolian Plateau. In East to West: Current Approaches to Medieval Archaeology. Edited by Scott Stull. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 140–154. [Google Scholar]

- Cassis, Marica, Anthony J. Lauricella, Katie Tardio, Madelynn von Baeyer, Scott Coleman, Sarah E. Adcock, Benjamin S. Arbuckle, and Alexia Smith. 2019. Regional Patterns of Transition at Çadır Höyük in the Byzantine Period. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 7: 321–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, Adrian M. 2012. Routine Magic, Mundane Ritual: Towards a Unified Notion of Depositional Practice. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 31: 283–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, John. 1997. The Origin of Tells in Eastern Hungary. In Neolithic Landscapes. Edited by Peter Topping Oxbow Monographs. Oxford: Oxbow, vol. 2, pp. 139–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chippendale, Christopher R. 1992. Grammars of Archaeological Design. In Representations in Archaeology. Edited by Jean-Claude Gardin and Christopher S. Peebles. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 251–76. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Billie Jean. 2002. Necromancy, Fertility and the Dark Earth: The use of Ritual Pits in Hittite Cult. In Magic and Ritual in the Ancient World (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 141). Edited by Paul Mirecki and Marvin Meyer. Leiden, New York and Köln: E.J. Brill, pp. 224–41. [Google Scholar]

- Croucher, Karina, and Ellen Belcher. 2017. Prehistoric Figurines in Anatolia (Turkey). In The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Figurines. Edited by Timothy Insoll. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 443–68. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey, Kim. 1999. Framing Places: Mediating Power in Built Form. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Düring, Bleda. 2011. Millennia in the Middle? Reconsidering the Chalcolithic of Asia Minor. In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Edited by Sharon R. Steadman and Gregory McMahon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 796–812. [Google Scholar]

- Duru, Refik. 1996. Kuruçay Höyük II: Results of Excavations 1978–88, The Late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age Settlements. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu. [Google Scholar]

- Ekroth, Gunnel. 2017. Bare Bones: Zooarchaeology and Greek Sacrifice. In Animal Sacrifice in the Ancient Greek World. Edited by Sarah Hitch and Ian Rutherford. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 15–47. [Google Scholar]

- Erdal, Selim Yılmaz. 2019. Interpreting Subadult Burials and Headshaping at Çadır Höyük. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 7: 379–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğu, Burçin. 2009. Ritual Symbolism in the Early Chalcolithic Period of Central Anatolia. Journal for Interdisciplinary Research on Religion and Science 5: 129–51. [Google Scholar]

- Esin, Ufuk. 2000. Değirmentepe (Malatya) Kurtarma Kazıları. In Türkiye Arkeolojisi ve İstanbul Üniversitesi (1932–1999). Edited by Oktay Belli. İstanbul: İstanbul Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Yayın, pp. 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Marian H. 2010. Object Agency? Spatial Perspective, Social Relations, and the Stele of Hammurabi*. In Agency and Identity in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Sharon R. Steadman and Jennifer C. Ross. Sheffield: Taylor and Francis, pp. 148–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fowles, Severin M. 2012. An Archaeology of Doings: Secularism and the Study of Pueblo Religion. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research. [Google Scholar]

- Frangipane, Marcella. 2009. Rise and Collapse of the Late Uruk centres in Upper Mesopotamia and Eastern Anatolia. Scienze Dell’Antichitá: Storia Archaeologia Antropologia 15: 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, James G., Sir. 1890. The Golden Bough. London: Macmillan and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Gebel, Hans G. K. 2002. Walls: Loci of Forces. In Magic Practices and Ritual in the Near Eastern Neolithic. Proceedings of a Workshop Held at the 2nd ICAANE, Copenhagen University, May 2000. Edited by Hans-Georg. K. Gebel, Bo D. Hermansen and Charlott H. Jensen. Berlin: Ex Oriente, pp. 119–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gebel, Hans G. K., Bo D. Hermansen, and Charlott H. Jensen, eds. Magic Practices and Ritual in the Near Eastern Neolithic. Paper presented at the 2nd ICAANE, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen, Fokke A. 2003. Local Identities: Landscape and Community in the Late Prehistoric Meuse-Demer-Scheldt Region. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gülçur, Sevil, and Yücel Kiper. 2007. Güvercinkayası 2005 Yılı Kazısı Ön Raporu. Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı 28: 111–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hackley, Laurel D., Stephanie L. Selover, and Sharon R. Steadman. 2018. The Persistence of Social and Spatial Memory at Prehistoric Çadır Höyük. International Journal of the Constructed Environment 9: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, Graham. 2005. Animism: Respecting the Living World. London: Hurst. [Google Scholar]

- Hauptmann, Harald. 1975. Die Architektur: Die Felsspalte D. In Das hethitische Felsheiligtum Yazılıkaya. BoHa IX. Edited by Kurt Bittel. Berlin: Gebr. Mann, pp. 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Helmer, Daniel, Lionel Gourichon, and Danielle Stordeur. 2004. À l’aube de la domestication animale: Imaginaire et symbolisme animal dans les premières sociétés néolithiques du nord du Proche-Orient. Anthropozoologica 39: 143–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hendon, Julia A. 2000. Having and Holding: Storage, Memory, Knowledge, and Social Relations. American Anthropologist 102: 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendon, Julia A. 2010. Houses in a Landscape: Memory and Everyday Life in Mesoamerica. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herva, Vesa-Pekka. 2005. The Life of Buildings: Minoan Building Deposits in an Ecological Perspective. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 24: 215–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herva, Vesa-Pekka, and Timo Yilmaunu. 2009. Folk Beliefs, Special Deposits, and Engagement with the Environment in Early Modern Northern Finland. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 28: 234–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillson, Simon W., Clark S. Larsen, Başak Boz, Marin A. Pilloud, Joshua W. Sadvari, Sabrina C. Agarwal, Bonnie Glencross, Patrick Beauchesne, Jessica A. Pearson, Christopher B. Ruff, and et al. 2013. The Human Remains I: Interpreting Community Structure, Health and Diet in Neolithic Çatalhöyük. In Humans and Landscapes of Çatalhöyük: Reports from the 2000–2008 Seasons. Edited by Ian Hodder. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, pp. 339–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, Ian. 2006. The Leopard’s Tale: Revealing the Mysteries of Turkey’s Ancient "Town". London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, Ian, ed. 2010. Religion in the Emergence of Civilization: Çatalhöyük as a Case Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, Ian. 2016. More on History Houses at Çatalhöyük: A Response to Carleton et al. Journal of Archaeological Science 67: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, Ian, and Peter Pels. 2010. History Houses: A New Interpreatation of Archtectural Elaboration at Çatalhöyük. In Religion in the Emergence of Civilization: Çatalhöyük as a Case Study. Edited by Ian Hodder. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 163–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hubert, Henri, and Marcel Mauss. 1902. Esquisse d’une Théorie Générale de la Magie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Timothy. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Timothy. 2006. Rethinking the Animate, Re-animating Thought. Ethnos 71: 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, Bernd. 1985. Body, House and City: The Intertwinings of Embodiment, Inhabitation and Civilization. In Dwelling, Place and Environment: Towards a Phenomenology of Person and World. Edited by David Seamon and Robert Mugerauer. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff, pp. 215–25. [Google Scholar]

- Khambatta, Ismet. 1989. The Meaning of Residence in Traditional Hindu Society. In Dwellings, Settlements and Tradition: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. Edited by Jean-Paul Bourdier and Nezar Alasayyad. Lanham: University Press of America, pp. 257–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kunen, Julie L., Mary Jo Galindo, and Erin Chase. 2002. Pits and Bones: Identifying Maya Ritual Behavior in the Archaeological Record. Ancient Mesoamerica 13: 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Richard. 1985. The Dwelling Door: Towards a Phenomenology of Transition. In Dwelling, Place and Environment: Towards a Phenomenology of Person and World. Edited by David Seamon and Robert Mugerauer. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff, pp. 201–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lercari, Nicola, and Gesualdo Busacca. 2020. A Glimpse through Time and Space: Visualizing Spatial Continuity and History Making at Çatalhöyük, Turkey. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 8: 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, Seton, and James Mellaart. 1962. Beycesultan: The Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age Levels. vol. 1. Occasional Publications of the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara 6. London: British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1925. Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays. New York: Doubleday Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, M. Chris. 2014a. The Material Culture of Ritual Concealments in the United States. Historical Archaeology 48: 52–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, M. Chris. 2014b. Magic, Religion, and Ritual in Historical Archaeology. Historical Archaeology 48: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, Michele. 2014. Early Bronze Age Burial Customs across the Central Anatolian Plateau: A View from Demircihöyük Sariket. Anatolian Studies 64: 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeorge, Photini J. P. 2013. Intramural Infant Burials in the Aegean Bronze Age: Reflections on Symbolism and Eschatology with Particular Reference to Crete. 2èmes Rencontres D’archéologie de l’IFEA: Le Mort dans la ville Pratiques, Contextes et Impacts des Inhumations Intra-muros en Anatolie, du Début de l’Age du Bronze à l’époque Romaine. Nov 2011. Istanbul: Bayoğlu, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, Gregory. 2002. Comparative Observations on Hittite Rituals. In Recent Development in Hittite Archaeology and History: Papers in Memory of Hans G. Güterbock. Edited by K. Aslıhan Yener and Harry A. Hoffner Jr. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 127–35. [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield, Ralph. 1987. The Archaeology of Ritual and Magic. London: Batsford. [Google Scholar]

- Michalowski, Piotr. 1985. On Some Early Sumerian Magical Texts. Orientalia 54: 216–25. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Alison. 2009. Hearth and Home: The Burial of Infants within Romano British Domestic Contexts. Childhood in the Past 2: 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, Sharon K. 2008. Çatalhöyük’s Foundation Burials: Ritual Child Sacrifice or Convenient Deaths? In Babies Reborn: Infant/Child Burials in Pre- and Protohistory. Edited by Krum Bacvarov. BAR International Series 1832. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Moses, Sharon K. 2012. Sociopolitical Implications of Neolithic Foundations Deposits and the Possibility of Child Sacrifice: A Case Study at Çatalhöyük, Turkey. In Sacred Killing: The Archaeology of Sacrifice in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Anne M. Porter and Glenn M. Schwartz. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Miriam. 2018. Foundation Deposits and Strategies of Place-Making at Tell el-Dab’a/Avaris. Near Eastern Archaeology 81: 182–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Carolyn M. 2010. Magical Deposits at Çatalhöyük: A Matter of Time and Place? In Spirituality and Religious Ritual in the Emergence of Civilization. Çatalhöyük as a Case Study. Edited by Ian Hodder. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 300–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Carolyn M., and Peter Pels. 2014. Using "Magic" to Think from the Material: Tracing Distributed Agnecy, Revelation, and Concealment at Çatalhöyük. In Religion at Work in a Neolithic Society. Edited by Ian Hodder. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 187–224. [Google Scholar]

- Özbaşaran, Mihriban. 1998. The Heart of a House: The Hearth––Aşıklı Höyük, A Pre-Pottery Neolithic Site in Central Anatolia. In Light on Top of the Black Hill. Edited by Güven Arsebük, Machteld J. Mellink and Wulf Schirmer. Istanbul: Ege Yayınları, pp. 555–66. [Google Scholar]

- Özbek, Metin. 2001. Cranial Deformation in a Subadult Sample from Değirmentepe (Chalcolithic, Turkey). American Journal of Physical Anthropology 115: 238–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgen, Engin, and Barbara Helwing. 2003. On the Shifting Border Between Mesopotamia and the West: Seven Seasons of Joint Turkish-German Excavations at Oylum Höyük. Anatolica 29: 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztan, Aliye. 2007. Niğde-Bor Ovası’nda Bir Neolitik Yerleşim. In Türkiye’de Neolitik Dönem. Anadolu’da Uyarlığın Doğuşu ve Avrupa’ya Yayılımı. Yeni Kazılar—Yeni Bulgular. Edited by Mehmet Özdoğan and Nezıh Başgelen. Edited by Mehmet Özdoğan and Nezıh Başgelen. İstanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları, pp. 223–35. [Google Scholar]

- Parker Pearson, Michael, and Colin Richards. 1994. Ordering the World: Perceptions of Architecture, Space and Time. In Architecture and Order: Approaches to Social Space. Edited by Michael Parker Pearson and Colin Richards. London: Routledge, pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Joris, and Klaus Schmidt. 2004. Animals in the Symbolic World of Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, South-eastern Turkey: A Preliminary Assessment. Anthropozoologica 39: 179–218. [Google Scholar]

- Pilloud, Marin A., Scott D. Haddow, Christopher J. Knüsel, Clark S. Larsen, and Mehmet Somel. 2020. Social Memory and Mortuary Practices in Neolithic Anatolia. In The Poetics of Processing: Memory Formation, Identity, and the Handling of the Dead. Edited by Anna J. Osterholtz. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, pp. 145–65. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, Peter R. W. 2013. Hittite Animal Sacrifice: Integrating Zooarchaeology and Textual Analysis. In Bones, Behaviour and Belief: The Zooarchaeological Evidence as a Source for Ritual Practice in Ancient Greece and Beyond. Edited by Gunnel Ekroth and Jenny Wallenstein. Stockholm: Svenska Institutet i Athen, pp. 101–14. [Google Scholar]

- Reiner, Erica. 1995. Astral Magic in Babylonia. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 85. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Arlene. 1986. Cities of Clay: The Geoarchaeology of Tells. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Jennifer C., Gregory McMahon, Yağmur Heffron, Sarah E. Adcock, Sharon R. Steadman, Benjamin S. Arbuckle, Alexia Smith, and Madelynn von Baeyer. 2019a. Anatolian Empires: Local Experiences from Hittites to Phrygians at Çadır Höyük. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 7: 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Jennifer C., Sharon R. Steadman, Gregory McMahon, Sarah E. Adcock, and Joshua W. Cannon. 2019b. When the Giant Falls: Endurance and Adaptation at Çadır Höyük in the Context of the Hittite Empire and its Collapse. Journal of Field Archaeology 44: 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, Mitchell. 2011. Interaction of Uruk and Northern Late Chalcolithic Societies in Anatolia. In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Edited by Sharon R. Steadman and Gregory McMahon. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 813–35. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Nerissa, and Stephanie Meece. 2006. Animal Representations and Animal Remains at Çatalhöyük. In Çatalhöyük Perspectives: Reports from the 1995–99 Seasons. Edited by Ian Hodder. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, pp. 209–30. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Nerissa, Louise Martin, and Katheryn C. Twiss. 2009. Building Memories: Commemorative Deposits at Çatalhöyük. Anthropozoologica 44: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, Nerissa, Katherine I. Wright, Tristan Carter, Sheena Ketchum, Philippa Ryan, Nurcan Yalman, Roddy Regan, Mirjana Stevanović, and Marina Milić. 2014. Bringing Down the House: House Closing Deposits at Çatalhöyük". In Humans and Landscapes of Çatalhöyük: Reports from the 2000–2008 Seasons: Catalhoyuk Research Project Volume 8. Edited by Ian Hodder. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California, pp. 109–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Klaus. 2011. Göbekli Tepe: A Neolithic Site in Southestern Anatolia. In Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Edited by Sharon R. Steadman and Gregory McMahon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 917–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schoop, Ulf-Dietrich. 2005. Das anatolische Chalkolithikum. Eine chronologische Untersuchung zur vorbronzezeitlichen Kultursequenz im nördlichen Zentralanatolien und den angrenzenden Gebieten. Remshalden-Grunbach: BA Greiner. [Google Scholar]

- Schoop, Ulf-Dietrich. 2009. Ausgrabungen in Çamlıbel Tarlası 2008. Archäologischer Anzeiger 2009: 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Schoop, Ulf-Dietrich. 2011a. The Chalcolithic on the Plateau. The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Edited by Sharon R. Steadman and Gregory McMahon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 150–73. [Google Scholar]

- Schoop, Ulf-Dietrich. 2011b. Çamlıbel Tarlası, ein metallverarbeitender Fundplatz des vierten Jhartausends v. Chr. Im nördlichen Zentralanatolien. In Anatolian Metal V. Edited by Ünsal Yalçın. Bochum: Deutsches Bergbau-Museum Bochem, pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Schoop, Ulf-Dietrich. 2015. Çamlıbel Tarlası: Late Chalcolithic Settlement and Economy in the Budaközü Valley (North-Central Anatolia). In The Archaeology of Anatolia: Recent Work (2011–2014). Edited by Sharon Steadman and Gregory McMahon. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, vol. 1, pp. 46–67. [Google Scholar]

- Schwemer, Daniel. 2011. Magic Rituals: Conceptualization and Performance. In The Oxford Handbok of Cuneiform Culture. Edited by Karen Radner and Eleanor Robson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 418–42. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Eleanor. 1991. Animal and Infant Burials in Romano-British Villas: Revitalization Movement. In Sacred and Profane: Proceedings of a Conference on Archaeology, Ritual and Religion. Oxford 1989. Edited by Paul Garwood, David Jennings, Robin Skeates and Judith Toms. Oxford University Committee for Archaeology Monograph 32. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 116–21. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Eleanor. 1999. The Archaeology of Infancy and Infant Death. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Selover, Stephanie, and Pınar Durgun. 2019. Reexamining Burials and Cemeteries in Early Bronze Age Anatolia. In The Archaeology of Anatolia, Volume III: Recent Discoveries (2017–2018). Edited by Sharon R. Steadman and Gregory McMahon. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 271–83. [Google Scholar]

- Selover, Stephanie, Laurel D. Hackley, and Sharon R. Steadman. Forthcoming. ‘Work/Life Balance’ in the Late Chalcolithic: Variations in Household Activities at Çadır Höyük in Central Anatolia. In No Place Like Home: Ancient Near Eastern Houses and Households. Edited by Laura Battini, Aaron Brody and Sharon R. Steadman. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Soysal, Oğuz, and Aygül Süel. 2016. The Hattian-Hittite Foundation Rituals from Ortaköy (II). Fragments to CTH 726 "Rituel Bilingue de foundation d’un temple d’ou un palais. In Audias Fabulas Veteres. Anatolian Studies in Honor of Jana Součková-Siegelová. Edited by Šárka Velhartiká. Leiden: Brill, pp. 320–64. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, Sharon R. 2005. Reliquaries on the Landscape: Mounds as Matrices of Human Cognition. In Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives. Edited by Susan Pollock and Reinhard Bernbeck. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 286–307. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, Sharon R., and Gregory McMahon. 2015. Recent Work (2013–2014) at Çadır Höyük on the North Central Anatolian Plateau. In The Archaeology of Anatolia: Recent Discoveries (2011–2014). Edited by Sharon R. Steadman and Gregory McMahon. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, vol. I, pp. 69–97. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, Sharon R., and Jennifer C. Ross. 2020. The Old Becomes New: Material Culture and Architectural Continuity on an Anatolian Höyük. In Current Approaches to Tells in the Prehistoric Old World. Edited by Antonio Blanco-González and Tobias L. Kienlin. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, Sharon R., Gregory McMahon, Jennifer C. Ross, Marica Cassis, T. Emre Şerifoğlu, Benjamin S. Arbuckle, Sarah E. Adcock, Songül Alpaslan Roodenberg, Madelynn von Baeyer, and Anthony J. Lauricella. 2015. The 2013 and 2013 Excavation Seasons at Çadır Höyük on the Anatolian North Central Plateau. Anatolica 41: 87–124. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, Sharon R., T. Emre Şerifoğlu, Gregory McMahon, Stephanie Selover, Laurel D. Hackley, Burcu Yıldırım, Anthony J. Lauricella, Benjamin S. Arbuckle, Sarah E. Adcock, Katie Tardio, and et al. 2017. Recent Discoveries (2015–2016) at Çadır Höyük on the North Central Plateau. Anatolica 43: 203–50. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, Sharon R., Benjamin S. Arbuckle, and Gregory McMahon. 2018. Pivoting East: Çadır Höyük, Transcaucasia, and Complex Connectivity in the Late Chalcolithic. Documenta Praehistorica XLV: 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steadman, Sharon R., Gregory McMahon, T. Emre Şerifoğlu, Marica Cassis, Anthony J. Lauricella, Laurel D. Hackley, Stephanie Selover, Burcu Yıldırım, Benjamin S. Arbuckle, Madelynn von Baeyer, and et al. 2019a. The 2017–2018 Seasons at Çadır Höyük on the North Central Plateau. Anatolica 45: 77–119. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, Sharon R., Gregory McMahon, and Jennifer C. Ross. 2019b. Chalcolithic, Iron Age, and Byzantine Investigations at Çadır Höyük: The 2017 and 2018 Seasons. In The Archaeology of Anatolia: Recent Discoveries (2017–2018). Edited by Sharon R. Steadman and Gregory McMahon. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, vol. III, pp. 32–52. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, Sharon R., Laurel D. Hackley, Stephanie Selover, Burcu Yıldırım, Madelynn von Baeyer, Benjamin Arbuckle, Ryan Robinson, and Alexia Smith. 2019c. Early Lives: The Late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age at Çadır Höyük. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 7: 271–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, Sharon R., Gregory McMahon, Benjamin S. Arbuckle, Madelynn von Baeyer, Alexia Smith, Burcu Yıldırım, Laurel D. Hackley, Stephanie Selover, and Stefano Spagni. 2019d. Stability and Change at Çadır Höyük in Central Anatolia: A Case of Late Chalcolithic Globalisation? Anatolian Studies 69: 21–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, Sharon R., Jennifer C. Ross, and Marica Cassis. Forthcoming. The Land that Time Forgot: Five Millennia of Settlement at Çadır Höyük on the Anatolian Plateau. In From Households to Empires: Papers in Honor of Bradley J. Parker. Edited by Jason R. Kennedy and Patrick Mullins. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Taussig, Michael. 1998. Viscerality, Faith and Skepticism: Another Theory of Magic. In Near Ruins: Cultural Theory at the End of the Century. Edited by Nicholas B. Dirks. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 221–56. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Jayne Leigh. 2017. Late Chalcolithic Skeletal Remains and Associated Mortuary Practices from Çamlıbel Tarlası in Central Anatolia. In Children, Death, and Burial: Archaeological Discourses. Edited by Eileen Murphy and Mélie Le Roy. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Yi-Fu. 1977. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. London: Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- van Gennep, Arnold. 1909. Les Rites de Passage. Paris: A. et J. Picard. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven, Marc. 2002a. Transformations of Society: The Changing Role of Ritual and Symbolism in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B and Pottery Neolithic Periods in the Levant and South-east Anatolia. Paléorient 28: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, Marc. 2002b. Ritual and Ideology in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B of the Levant and Southeast Anatolia. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 12: 233–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villing, Alexandra. 2017. Don’t Kill the Goose That Lays the Golden Egg? Some Thoughts on Bird Sacrifices in Ancient Greece. In Animal Sacrifice in the Ancient Greek World. Edited by Sarah Hitch and Ian Rutherford. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 63–102. [Google Scholar]

- von Baeyer, Madelynn. 2018. Seeds of Complexity: An Archaeobotanical Study of Incipient Social Complexity at Late Chalcolithic Çadır Höyük, Turkey. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Connecticut, Stamford, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- von Baeyer, Madelynn, Alexia Smith, and Sharon R. Steadman. 2021. Expanding the Plain: Using Archaeobotany to Examine Adaptation to 5.2 kya Climate Change Event during the Anatolian Late Chalcolithic at Çadır Höyük. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Osten, Hans Henning. 1937. The Alishar Hüyük. Seasons of 1930–32 (Part 1). University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications 28, Researches in Anatolia 7. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waterson, Roxana. 1990. The Living House: An Anthropology of Architecture in Southeast-East Asia. Singapore: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, Trevor. 2015. Religion as Practice in Neolithic Societies. In Defining the Sacred: Approaches to the Archaeology of Religion in the Near East. Edited by Nicola Laneri. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 153–60. [Google Scholar]

- Willerslev, Rane. 2007. Soul Hunters: Hunting, Animism, and Personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, Peter, and Ann Woodward. 2004. Dedicating the Town: Urban Foundation Deposits in Roman Britain. World Archaeology 36: 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, Burcu, and Sharon R. Steadman. 2021. Chalcolithic Religion and Ritual on the Anatolian Plateau. In The Archaeology of Anatolia Volume IV: Recent Discoveries (2018–2020). Edited by Sharon R. Steadman and Gregory McMahon. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press, pp. 370–393. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, Burcu, Laurel D. Hackley, and Sharon R. Steadman. 2018. Sanctifying the House: Child Burial in Prehistoric Anatolia. Near Eastern Archaeology 81: 164–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Early Chalcolithic | ca. 6100–5500 BCE |

| Middle Chalcolithic | ca. 5500–4250 BCE |

| Late Chalcolithic | ca. 4250–3000 BCE |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hackley, L.D.; Yıldırım, B.; Steadman, S. Not Seeing Is Believing: Ritual Practice and Architecture at Chalcolithic Çadır Höyük in Anatolia. Religions 2021, 12, 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080665

Hackley LD, Yıldırım B, Steadman S. Not Seeing Is Believing: Ritual Practice and Architecture at Chalcolithic Çadır Höyük in Anatolia. Religions. 2021; 12(8):665. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080665

Chicago/Turabian StyleHackley, Laurel Darcy, Burcu Yıldırım, and Sharon Steadman. 2021. "Not Seeing Is Believing: Ritual Practice and Architecture at Chalcolithic Çadır Höyük in Anatolia" Religions 12, no. 8: 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080665

APA StyleHackley, L. D., Yıldırım, B., & Steadman, S. (2021). Not Seeing Is Believing: Ritual Practice and Architecture at Chalcolithic Çadır Höyük in Anatolia. Religions, 12(8), 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080665