Insecure Attachment to God and Interpersonal Conflict

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. An Interpersonal Conceptualization of Religiousness

1.2. Trait Self-Control and Interpersonal Outcomes

1.3. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

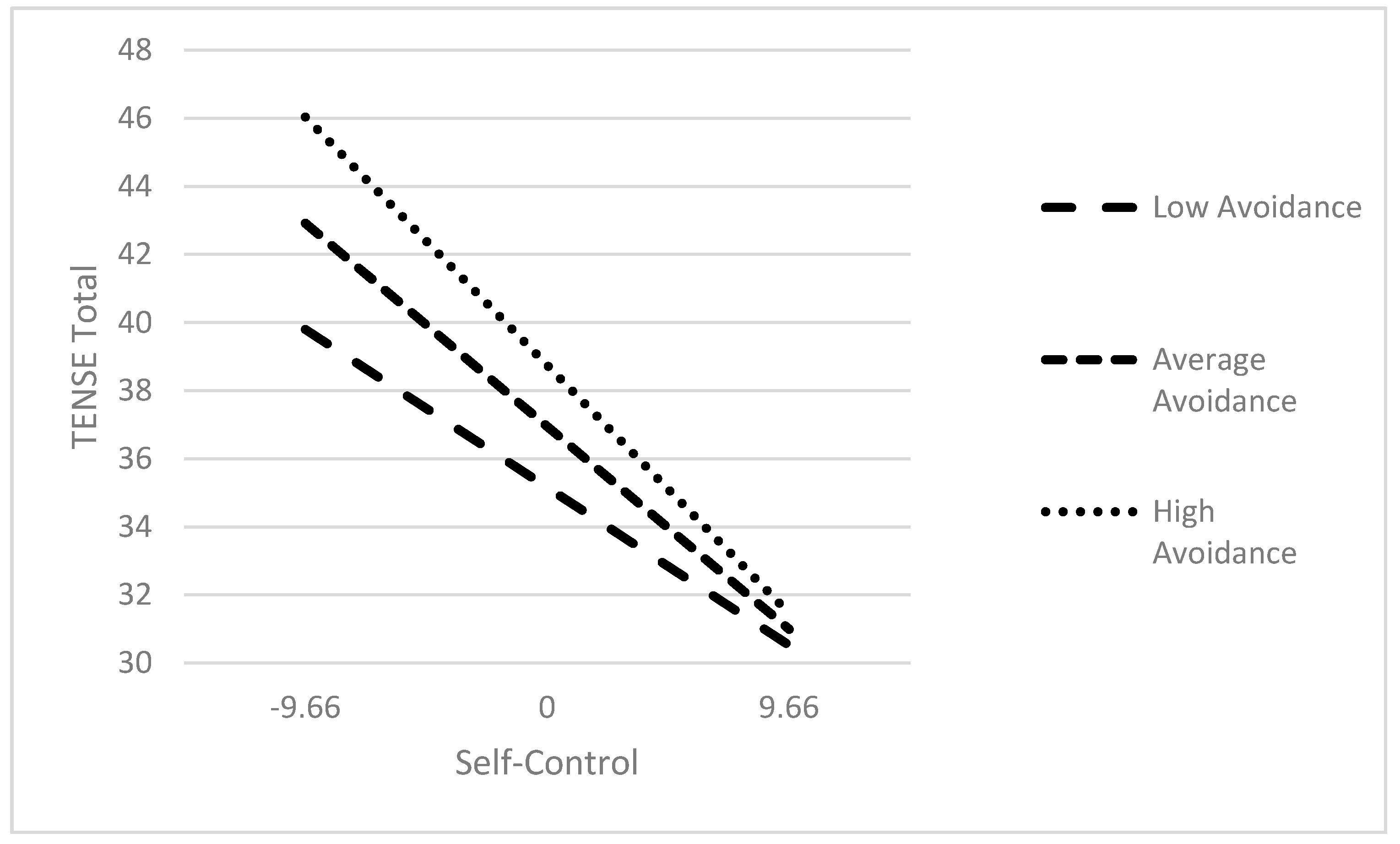

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baumeister, Roy F., and Jessica L. Alquist. 2009. Self-regulation as a limited resource: Strength model of control and depletion. In Psychology of Self-Regulation: Cognitive, Affective, and Motivational Processes. Edited by Joseph P. Forgas, Roy F. Baumeister and Dianne M. Tice. New York: Psychology Press, vol. 11, pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, Roy F., Matthew Gailliot, C. Nathan DeWall, and Megan Oaten. 2006. Self-Regulation and Personality: How Interventions Increase Regulatory Success, and How Depletion Moderates the Effects of Traits on Behavior. Journal of Personality 74: 1773–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, Richard. 2006. God as a secure base: Attachment to God and theological exploration. Journal of Psychology and Theology 34: 125–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Richard, and Angie McDonald. 2004. Attachment to God: The Attachment to God Inventory, tests of working model correspondence, and an exploration of faith group differences. Journal of Psychology and Theology 32: 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman, John H. I. V. 2017. Do birds of a feather really flock together? Friendships, self-control similarity and deviant behaviour. British Journal of Criminology 57: 1208–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman, John H. I. V., Marvin D. Krohn, Chris L. Gibson, and John M. Stogner. 2012. Investigating friendship quality: An exploration of self-control and social control theories’ friendship hypotheses. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 41: 1526–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, John. 1951. Maternal care and mental health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 3: 355–533. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, John. 1982. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 52: 664–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, Matt, Christopher G. Ellison, and Jack P. Marcum. 2010. Attachment to God, images of God, and psychological distress in a nationwide sample of Presbyterians. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 20: 130–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burgess, Kim B., Peter J. Marshall, Kenneth H. Rubin, and Nathan A. Fox. 2003. Infant attachment and temperament as predictors of subsequent externalizing problems and cardiac physiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 44: 819–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkley, Edward, Darshon Anderson, and Jessica Curtis. 2011. You wore me down: Self-control strength and social influence. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 5: 487–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ridder, Denise T. D., Gerty Lensvelt-Mulders, Catrin Finkenauer, F. Marijn Stok, and Roy F. Baumeister. 2012. Taking stock of self-control: A meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Personality and Social Psychology Review 16: 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- DeKlyen, Michelle, Mathhew L. Speltz, and Mark T. Greenberg. 1998. Fathering and early onset conduct problems: Positive and negative parenting, father–son attachment, and the marital context. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 1: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exline, Julie J., Steffany J. Homolka, and Valencia A. Harriott. 2016. Divine struggles: Links with body image concerns, binging, and compensatory behaviours around eating. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 19: 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, Thomas A., and Wade C. Rowatt. 2014. Examining a purported association between attachment to God and scrupulosity. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 6: 230–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finkel, Eli J., Grainne M. Fitzsimons, and Michelle R. van Dellen. 2016. Self-regulation as a transactive process: Reconceptualizing the unit of analysis for goal setting, pursuit, and outcomes. In Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications, 3rd ed. Edited by Kathleen D. Vohs and Roy F. Baumeister. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 264–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ghobary Bonab, Bonab, Maureen Miner, and Marie-Therese Proctor. 2013. Attachment to God in Islamic spirituality. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 7: 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilliom, Miles, Daniel S. Shaw, Joy E. Beck, Michael A. Schonberg, and JoElla L. Lukon. 2002. Anger regulation in disadvantaged preschool boys: Strategies, antecedents, and the development of self-control. Developmental Psychology 38: 222–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, Pehr, and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 2013. Religion, spirituality, and attachment. In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol 1): Context, Theory, and Research. Edited by In Kenneth I. Pargament, Julie J. Exline and James W. Jones. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 139–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtman, Michael B. 1991. Evaluating the interpersonalness of personality scales. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 17: 670–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankin, Benjamin L., Jon D. Kassel, and John R. Z. Abela. 2005. Adult Attachment Dimensions and Specificity of Emotional Distress Symptoms: Prospective Investigations of Cognitive Risk and Interpersonal Stress Generation as Mediating Mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 31: 136–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Terrence D., Christopher S. Bradley, Benjamin Dowd-Arrow, and Amy M. Burdette. 2019. Religious attendance and the social support trajectories of older Mexican Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 34: 403–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, Kevin D., Kevin S. Masters, Stephanie A. Hooker, John. M. Ruiz, and Timothy W. Smith. 2014. An interpersonal approach to religiousness and spirituality: Implications for health and well-being. Journal of Personality 82: 418–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, Kevin D., Paula G. Williams, and Timothy W. Smith. 2015. Interpersonal distinctions among hypochondriacal trait components: Styles, goals, vulnerabilities, and perceptions of health care providers. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 34: 459–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, Rachel, Barbara Dooley, and Amanda Fitzgerald. 2013. Interpersonal relationships and emotional distress in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 36: 351–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimball, Cynthia N., Chris J. Boyatzis, and Kaye V. Cook. 2013. Attachment to God: A qualitative exploration of emerging adults’ spiritual relationship with God. Journal of Psychology and Theology 41: 175–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, Lee A. 1992. An attachment-theory approach to the psychology of religion. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 2: 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leman, Joseph, III, Will Hunter, Thomas Fergus, and Wade Rowatt. 2018. Secure attachment to God uniquely linked to psychological health in a national, random sample of American adults. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 28: 162–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limke, Alicia, and Patrick B. Mayfield. 2011. Attachment to God: Differentiating the contributions of fathers and mothers using the Experiences in Parental Relationships Scale. Journal of Psychology and Theology 39: 122–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manapat, Patrick D., Michael C. Edwards, David P. MacKinnon, Russell A. Poldrack, and Lisa A. Marsch. 2021. A psychometric analysis of the Brief Self-Control Scale. Assessment 28: 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, Patrick M., and Charlotte N. Markey. 2009. A brief assessment of the interpersonal circumplex: The IPIP-IPC. Assessment 16: 352–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- May, Ross W., Gregory S. Seibert, Marcos A. Sanchez-Gonzalez, Michael C. Fitzgerald, and Frank D. Fincham. 2017. Dispositional self-control: Relationships with aerobic capacity and morning surge in blood pressure. Stress: The International Journal on the Biology of Stress 20: 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, Michael E., and Evan C. Carter. 2011. Waiting, tolerating, and cooperating: Did religion evolve to prop up humans’ self-control abilities? In Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications, 2nd ed. Edited by Kathleen D. Vohs and Roy F. Baumeister. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 422–37. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, Michael E., and Evan C. Carter. 2013. Religion, self-control, and self-regulation: How and why are they related? In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol 1): Context, Theory, and Research. Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament, Julie J. Exline and James W. Jones. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 123–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., Jo-Ann Tsang, and Sharon Brion. 2003. Personality traits in adolescence as predictors of religiousness in early adulthood: Findings from the Terman longitudinal study. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 29: 980–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., William T. Hoyt, David B. Larson, Harold G. Koenig, and Carl Thoresen. 2000. Religious involvement and mortality: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychology 19: 211–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, Elana R. 2018. Reproducing economic inequality: Longitudinal relations of self-control, social support, and maternal education. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 56: 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, Mario, and Philip R. Shaver. 2012a. Adult attachment orientations and relationship processes. Journal of Family Theory & Review 4: 259–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, Mario, and Philip R. Shaver. 2012b. Attachment theory expanded: A behavioral systems approach. In The Oxford Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology. Edited by Kay Deaux and Mark Snyder. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 467–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, Maureen. 2009. The impact of child-parent attachment, attachment to God and religious orientation on psychological adjustment. Journal of Psychology and Theology 37: 114–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Yan-Gang, Jian-Bin Li, and Alexander T. Vazsonyi. 2016. Self-control mediates the associations between parental attachment and prosocial behavior among Chinese adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences 96: 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orehek, Edward, Anna Vazeou-Nieuwenhuis, Ellen Quick, and Casey C. Weaverling. 2017. Attachment and self-regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 43: 365–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovic, Katja, Cassandra M. Chapman, and Timothy P. Schofield. 2021. Religiosity and volunteering over time: Religious service attendance is associated with the likelihood of volunteering, and religious importance with time spent volunteering. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 13: 136–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Russell E., III, and Michael B. Kitchens. 2016. Augustine or Philistine? College students’ sanctification of learning and its implications. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 26: 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, Aaron L., and Emily B. Ansell. 2013. Interpersonal theory of personality. In Handbook of psychology: Personality and Social Psychology, 2nd ed. Edited by Howard Tennen, Jerry Suls and Irving B. Weiner. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., vol. 5, pp. 141–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein, Diana S., and Harvey A. Horowitz. 1996. Adolescent attachment and psychopathology. (Attachment and Psychopathology, Part 2). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64: 244–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowatt, Wade C., and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 2002. Two dimensions of attachment to God and their relation to affect, religiosity, and personality constructs. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 637–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruehlman, Linda S., and Paul Karoly. 1991. With a little flak from my friends: Development and preliminary validation of the Test of Negative Social Exchange (TENSE). Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 3: 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahdra, Baljinder K., and Philip R. Shaver. 2013. Comparing attachment theory and Buddhist psychology. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 23: 282–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, Richard P., and Emilia Bagiella. 2002. Claims about religious involvement and health outcomes. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24: 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotter, Erica B., Jessica L. Grom, and Brenden Tervo-Clemmens. 2020. Don’t take it out on me: Displaced aggression after provocation by a romantic partner as a function of attachment anxiety and self-control. Psychology of Violence 10: 232–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrova, Olga, Tila Pronk, and Michail D. Kokkoris. 2020. Finding meaning in self-control: The effect of self-control on the perception of meaning in life. Self and Identity 19: 201–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tangney, June P., Roy F. Baumeister, and Angie L. Boone. 2004. High Self-Control Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success. Journal of Personality 72: 271–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, Bilge, Sera LeBlanc, and Joseph R. Ferrari. 2020. Relationship between academic procrastinaton and self-control: The mediational role of self-esteem. College Student Journal 54: 309–16. [Google Scholar]

- Valikhani, Ahmad, Mehdi R. Sarafraz, and Pooneh Moghimi. 2018. Examining the role of attachment styles and self-control in suicide ideation and death anxiety for patients receiving chemotherapy in Iran. Psycho-Oncology 27: 1057–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohs, Kathleen D., Catrin Finkenauer, and Roy F. Baumeister. 2011. The sum of friends’ and lovers’ self-control scores predicts relationship quality. Social Psychological and Personality Science 2: 138–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitehead, Alfred N. 1926. Religion in the making: Lowell lectures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama, Kandauda A. S., Chalandra M. Bryant, and Thulitha K. A. Wickrama. 2010. Perceived community disorder, hostile marital interactions, and self-reported health of African American couples: An interdyadic process. Personal Relationships 17: 515–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, Jerry S., and Ross Broughton. 1991. A geometric taxonomy of personality scales. European Journal of Personality 5: 343–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Paula G., Holly K. Rau, Matthew R. Cribbet, and Heather E. Gunn. 2009. Openness to experience and stress regulation. Journal of Research in Personality 43: 777–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Religion | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Atheist | 4 | 0.4 |

| Buddhist | 18 | 1.8 |

| Hindu | 8 | 0.8 |

| Jehovah’s Witness | 8 | 0.8 |

| Jewish | 26 | 2.6 |

| LDS | 10 | 1.0 |

| Muslim | 50 | 5.0 |

| New age | 4 | 0.4 |

| Lutheran | 25 | 2.5 |

| Roman Catholic | 219 | 22.0 |

| Episcopalian | 9 | 0.9 |

| Methodist | 28 | 2.8 |

| Presbyterian | 19 | 1.9 |

| Christian | 395 | 39.6 |

| Baptist | 75 | 7.5 |

| Pentecostal | 28 | 2.8 |

| Adventist | 3 | 0.3 |

| Taoist | 1 | 0.1 |

| Unitarian | 2 | 0.2 |

| Other or none of the above | 65 | 6.5 |

| AGS Avoidance | AGS Anxiety | BSCS | TENSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGS Avoidance | ||||

| AGS Anxiety | 0.45 * | |||

| BSCS | −0.32 * | −0.31 * | ||

| TENSE | 0.23 * | 0.35 * | −0.39 * | |

| Sample (n = 997) | ||||

| Mean | 16.51 | 11.83 | 42.22 | 37.58 |

| SD | 7.82 | 4.75 | 9.65 | 16.47 |

| α | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.96 |

| R | F(2, 953) | β Affiliation | β Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGS avoidance | 0.40 | 90.56 * | −0.37 * | 0.14 * |

| AGS anxiety | 0.29 | 44.78 * | −0.24 * | 0.16 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jordan, K.D.; Niehus, K.L.; Feinstein, A.M. Insecure Attachment to God and Interpersonal Conflict. Religions 2021, 12, 739. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090739

Jordan KD, Niehus KL, Feinstein AM. Insecure Attachment to God and Interpersonal Conflict. Religions. 2021; 12(9):739. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090739

Chicago/Turabian StyleJordan, Kevin D., Katie L. Niehus, and Ari M. Feinstein. 2021. "Insecure Attachment to God and Interpersonal Conflict" Religions 12, no. 9: 739. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090739