Belief in God and Psychological Distress: Is It the Belief or Certainty of the Belief?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures and Procedures

2.2.1. Belief in God

2.2.2. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

2.2.3. Meaning in Life

2.2.4. Comfort by God

2.2.5. Positive Religious Coping

2.2.6. Positive Reappraisal and Substance Use Coping

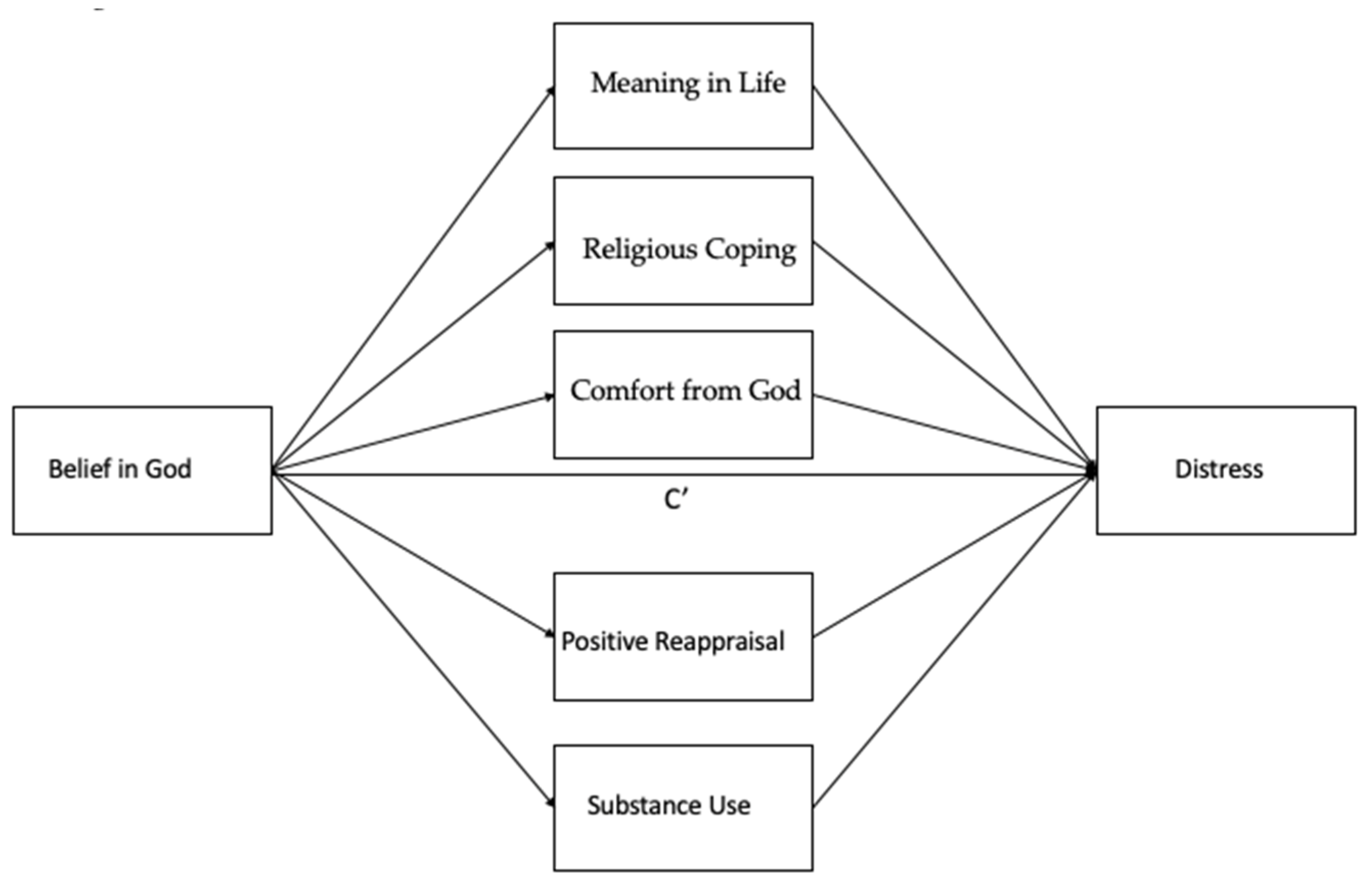

2.3. Statistical Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Belief in God and Depression

3.1.2. Belief in God and Anxiety

3.1.3. Belief in God and Stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AbdAleati, Naziha S., Nozarina Mohd Zaharim, and Yasmin Othman Mydin. 2016. Religiousness and mental health: Systematic review study. Journal of Religion and Health 55: 1929–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashouri, Fazilat Pour, Hosein Hamadiyan, Mohammad Nafisi, Afshin Parvizpanah, and Sepehr Rasekhi. 2016. The relationships between religion/spirituality and mental and physical health: A review. Disease and Diagnosis 5: 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, D., and Christopher John Lennings. 1993. Grief and religious belief: Does belief moderate depression? Death Studies 17: 487–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco-Ruggiero, Stephanie A. 2020. The relationship between Americans’ spiritual/religious beliefs and behaviors and mental health: New evidence from the 2016 General Social Survey. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health 22: 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, Nicholas A., Alyssa N. Rockenbach, Matthew J. Mayhew, Tiffani A. Riggers-Piehl, and Tara D. Hudson. 2017. College students’ appreciative attitudes toward atheists. Research in Higher Education 58: 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, Amber L., John P. Jameson, Terri Barrera, Laura L. Phillips, Natascha Lachner, Gina Evans, Ajani D.Jackson, and Melinda A. Stanley. 2012. An evaluation of the brief multidimensional measure of religiousness/spirituality in older patients with prior depression or anxiety. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 15: 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, Lauren M., Crystal L. Park, and Ian A. Gutierrez. 2020. Religious beliefs and well-being and distress in congestive heart failure patients. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 43: 437–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranney, Stephen. 2013. Do people who believe in God report more meaning in their lives? The existential effects of belief. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 638–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doane, Michael J., and Marta Elliott. 2015. Perceptions of discrimination among atheists: Consequences for atheist identification, psychological and physical well-being. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 7: 130–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doane, Michael J., Marta Elliott, and Portia S. Dyrenforth. 2014. Extrinsic religious orientation and well-being: Is their negative association real or spurious? Review of Religious Research 56: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcos, Florin, Kelly Hohl, Yifan Hu, and Sanda Dolcos. 2021. Religiosity and resilience: Cognitive reappraisal and coping self-efficacy mediate the link between religious coping and well-being. Journal of Religion and Health. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgell, Penny, Joseph Gerteis, and Douglas Hartmann. 2006. Atheists As “Other”: Moral boundaries and cultural membership in American society. American Sociological Review 71: 211–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie Juola, Ann Marie Yali, and William C. Sanderson. 2000. Guilt, discord, and alienation: The role of religious strain in depression and suicidality. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56: 1481–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie J., Todd W. Hall, Kenneth I. Pargament, and Valencia A. Harriott. 2017. Predictors of growth from spiritual struggle among Christian undergraduates: Religious coping and perceptions of helpful action by God are both important. The Journal of Positive Psychology 12: 501–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, Miguel, and Anna-Kaisa Newheiser. 2019. The effects of belief in God and science on acute stress. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice 6: 214–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. 1999. Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research. Kalamazoo: The Fetzer Institute, Available online: http://fetzer.org/resources/multidimensional-measurement-religiousnessspirituality-use-health-research (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Freud, Sigmund. 1959. Obsessive actions and religious practices. In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume IX (1906–1908): Jensen’s ‘Gradiva’and Other Works. London: Hogarth Press, pp. 115–28. First published 1907. [Google Scholar]

- Galen, Luke William, and James D. Kloet. 2011. Mental well-being in the religious and the non-religious: Evidence for a curvilinear relationship. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 14: 673–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, Terry Lynn, and Manal Guirguis-Younger. 2013. Religious and spiritual coping: Current theory and research. In APA handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol 1): Context, Theory, and Research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 349–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, Will M., and Maxine B. Najle. 2018. How many Atheists are there? Social Psychological and Personality Science 9: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Joseph, Ryan Cragun, Karen Hwang, and Jesse Smith. 2012. Forms, frequency, and correlates of perceived anti-Atheist discrimination. Secularism and Nonreligion 1: 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, Marcel. 2007. The stereotyping of nonreligious people by religious students: Contents and subtypes. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 46: 539–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, Julie D., and John R. Crawford. 2005. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology 44, Pt 2: 227–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirsh, Jacob B., Raymond A. Mar, and Jordan B. Peterson. 2012. Psychological entropy: A framework for understanding uncertainty-related anxiety. Psychological Review 119: 304–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horning, Sheena M., Hasker P. Davis, Michael Stirrat, and R. Elisabeth Cornwell. 2011. Atheistic, agnostic, and religious older adults on well-being and coping behaviors. Journal of Aging Studies 25: 177–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, William. 1958. The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature. New York: New American Library. First published 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Xiao-Rong, Juan-Juan Du, and Rui-Yuan Dong. 2017. Coping style, job burnout and mental health of university teachers of the millennial generation. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 13: 3379–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2009. Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: A review. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie 54: 283–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2012. Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012: 278730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krause, Neal. 2006. Religious doubt and psychological well-being: A longitudinal investigation. Review of Religious Research 47: 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 1970. Critique of Hegel’s ‘Philosophy of Right’. Edited and Translated by Annette Jolin and Joseph O’Malley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty, Kristy, Hanoch Livneh, and Lisa M. Wilson. 2004. Perceived uncertainty, spiritual well-being, and psychosocial adaptation in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitation Psychology 49: 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moreira-Almeida, Alexander, Francisco Lotufo Neto, and Harold G. Koenig. 2006. Religiousness and mental health: A review. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 28: 242–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moscati, Arden, and Briana Mezuk. 2014. Losing faith and finding religion: Religiosity over the life course and substance use and abuse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 136: 127–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, Patricia E., and George Fitchett. 2009. Belief in a concerned god predicts response to treatment for adults with clinical depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology 65: 1000–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Joseph Kennell, William Hathaway, Nancy Grevengoed, Jon Newman, and Wendy Jones. 1988. Religion and the problem-solving process: Three styles of coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 27: 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth, Margaret Feuille, and Donna Burdzy. 2011. The Brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions 2: 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, Crystal L. 2007. Religiousness/spirituality and health: A meaning systems perspective. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 30: 319–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Crystal L., Lucy Finkelstein-Fox, Shane J. Sacco, Tosca D. Braun, and Sara Lazar. 2021. How does yoga reduce stress? A clinical trial testing psychological mechanisms. Stress and Health 37: 116–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Han Nah, Sara E. LePine, Kaye Cook, and Catherine Steininger. 2019. Do Nonreligious Individuals Have the Same Mental Health and Well-Being Benefits as Religious Individuals? Journal of Psychology & Christianity 38: 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, Joanna, and Andrew James Peter Francis. 2017. Influence of religiosity on self-reported response to psychological therapies. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 20: 428–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, Mario Fernando Prieto, Helder H. Kamei, Patricia R. Tobo, and Giancarlo Lucchetti. 2018. Mechanisms behind religiosity and spirituality’s effect on mental health, quality of life and well-being. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 1842–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. n.d. Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Rasic, Daniel, Steve Kisely, and Donald B. Langille. 2011. Protective associations of importance of religion and frequency of service attendance with depression risk, suicidal behaviours and substance use in adolescents in Nova Scotia, Canada. Journal of Affective Disorders 132: 389–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrbaugh, John, and Richard Jessor. 1975. Religiosity in youth: A personal control against deviant behavior? Journal of Personality 43: 136–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberg, Corina R., Edward Alan Miller, Elizabeth Dugan, and Frank Porell. 2016. The protective effects of religiosity on depression: A 2-Year prospective study. The Gerontologist 56: 421–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosmarin, David H., Joseph S. Bigda-Peyton, Sarah J. Kertz, Nasya Smith, Scott L. Rauch, and Thröstur Björgvinsson. 2013. A test of faith in God and treatment: The relationship of belief in God to psychiatric treatment outcomes. Journal of Affective Disorders 146: 441–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Yves. 2012. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software 48: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schnitker, Sarah A., Benjamin Houltberg, William Dyrness, and Nanyamka Redmond. 2017. The virtue of patience, spirituality, and suffering: Integrating lessons from positive psychology, psychology of religion, and Christian theology. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 9: 264–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silton, Nava, Kevin Flannelly, Kathleen Galek, and Christopher Ellison. 2013. Beliefs about God and mental health among American adults. Journal of Religion and Health 53: 1285–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, Michael F., and Patricia Frazier. 2005. Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology 52: 574–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sternthal, Michelle J., David R. Williams, Marc A. Musick, and Anna C. Buck. 2010. Depression, anxiety, and religious Life: A search for mediators. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51: 343–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, Christy T., Eric Kuhn, Robyn D. Walser, and Kent D. Drescher. 2012. The relationship between religiosity, PTSD, and depressive symptoms in veterans in PTSD residential treatment. Journal of Psychology and Theology 40: 313–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandekerckhove, Joachim, Dora Matzke, and Eric-Jan Wagenmakers. 2015. Model Comparison and the Principle of Parsimony. Edited by Jerome R. Busemeyer, Zheng Wang, James T. Townsend and Ami Eidels. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishkin, Allon, Yochanan E. Bigman, Roni Porat, Nevin Solak, Eran Halperin, and Maya Tamir. 2016. God rest our hearts: Religiosity and cognitive reappraisal. Emotion 16: 252–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilkinson, Peter J., and Peter G. Coleman. 2010. Strong beliefs and coping in old age: A case-based comparison of atheism and religious faith. Ageing & Society 30: 337–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Benjamin T., Everett L. Worthington Jr., Julie Juola Exline, Ann Marie Yali, Jamie D. Aten, and Mark R. McMinn. 2010. Development, refinement, and psychometric properties of the Attitudes Toward God Scale (ATGS-9). Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 2: 148–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Belief in God | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2. Depression | −0.16 ** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3. Anxiety | −0.02 | 0.61 ** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 4. Stress | −0.04 | 0.70 ** | 0.75 ** | 1.00 | |||||

| 5. Meaning | 0.34 ** | −0.40 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.16 ** | 1.00 | ||||

| 6. Comfort by God | 0.88 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.34 ** | 1.00 | |||

| 7. Positive Religious Coping | 0.76 ** | −0.09 + | 0.09 + | 0.04 | 0.35 ** | 0.84 ** | 1.00 | ||

| 8. Positive Reappraisal | 0.15 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.09 + | −0.11 * | 0.34 ** | .21 ** | 0.22 ** | 1.00 | |

| 9. Substance Use Coping | −0.12 * | 0.27 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.25 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.10 + | −0.04 | −0.12 * | 1.00 |

| M | 2.56 | 8.51 | 8.08 | 11.46 | 21.24 | 25.55 | 14.31 | 11.80 | 5.48 |

| SD | 1.47 | 8.80 | 7.94 | 8.69 | 6.29 | 20.25 | 6.95 | 2.70 | 2.62 |

| Scale Range | 1–5 | 0–42 | 0–42 | 0–42 | 5–35 | 0–50 | 7–28 | 4–16 | 4–16 |

| Variable | Model A | Model B | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B1 | B2 | ||

| Depression | −0.164 | 0.238 | −0.409 | 3.388 |

| Anxiety | −0.023 | 0.482 | −0.513 | 5.208 * |

| Stress | −0.038 | 0.380 | −0.425 | 3.569 |

| Path and Variable | B | SE | 95% Lower CI | 95% Upper CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belief in God to mediators (paths a) | |||||

| Meaning in Life | 0.344 | 0.034 | 0.277 | 0.411 | <0.001 |

| Comfort by God | 0.880 | 0.007 | 0.866 | 0.894 | <0.001 |

| Positive Religious Coping | 0.765 | 0.014 | 0.738 | 0.793 | <0.001 |

| Positive Reappraisal | 0.154 | 0.039 | 0.077 | 0.230 | <0.001 |

| Substance Use Coping | −0.115 | 0.039 | −0.193 | −0.038 | 0.004 |

| Mediators to Depression (paths b) | |||||

| Meaning in Life | −0.347 | 0.038 | −0.422 | −0.273 | <0.001 |

| Comfort by God | −0.282 | 0.088 | −0.453 | −0.100 | 0.001 |

| Positive Religious Coping | 0.286 | 0.065 | 0.158 | 0.413 | <0.001 |

| Positive Reappraisal | −0.109 | 0.038 | −0.183 | −0.035 | 0.004 |

| Substance Use Coping | 0.198 | 0.035 | 0.129 | 0.267 | <0.001 |

| Direct effect of Belief in God on Depression (path c) | |||||

| Belief in God | −0.163 | 0.039 | −0.239 | −0.087 | <0.001 |

| Direct effect of Belief in God on Depression with mediators included (path c’) | |||||

| Belief in God | 0.025 | 0.075 | −0.122 | 0.172 | 0.739 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magin, Z.E.; David, A.B.; Carney, L.M.; Park, C.L.; Gutierrez, I.A.; George, L.S. Belief in God and Psychological Distress: Is It the Belief or Certainty of the Belief? Religions 2021, 12, 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090757

Magin ZE, David AB, Carney LM, Park CL, Gutierrez IA, George LS. Belief in God and Psychological Distress: Is It the Belief or Certainty of the Belief? Religions. 2021; 12(9):757. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090757

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagin, Zachary E., Adam B. David, Lauren M. Carney, Crystal L. Park, Ian A. Gutierrez, and Login S. George. 2021. "Belief in God and Psychological Distress: Is It the Belief or Certainty of the Belief?" Religions 12, no. 9: 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090757

APA StyleMagin, Z. E., David, A. B., Carney, L. M., Park, C. L., Gutierrez, I. A., & George, L. S. (2021). Belief in God and Psychological Distress: Is It the Belief or Certainty of the Belief? Religions, 12(9), 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090757