The Research on Islamic-Based Educational Leadership since 1990: An International Review of Empirical Evidence and a Future Research Agenda

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Islamisation has become part of the religious education discourse in postcolonial countries during 1940s–1990s and the debate about this ideology is still going on. Note that Islamisation should not be viewed as a unified or agreed concept because different and competing Islamic traditions (Shi’a, Sunni, or Sufi) may have their own definitions of Islamisation and the implications of Islamisation in the field of education (p. 2).

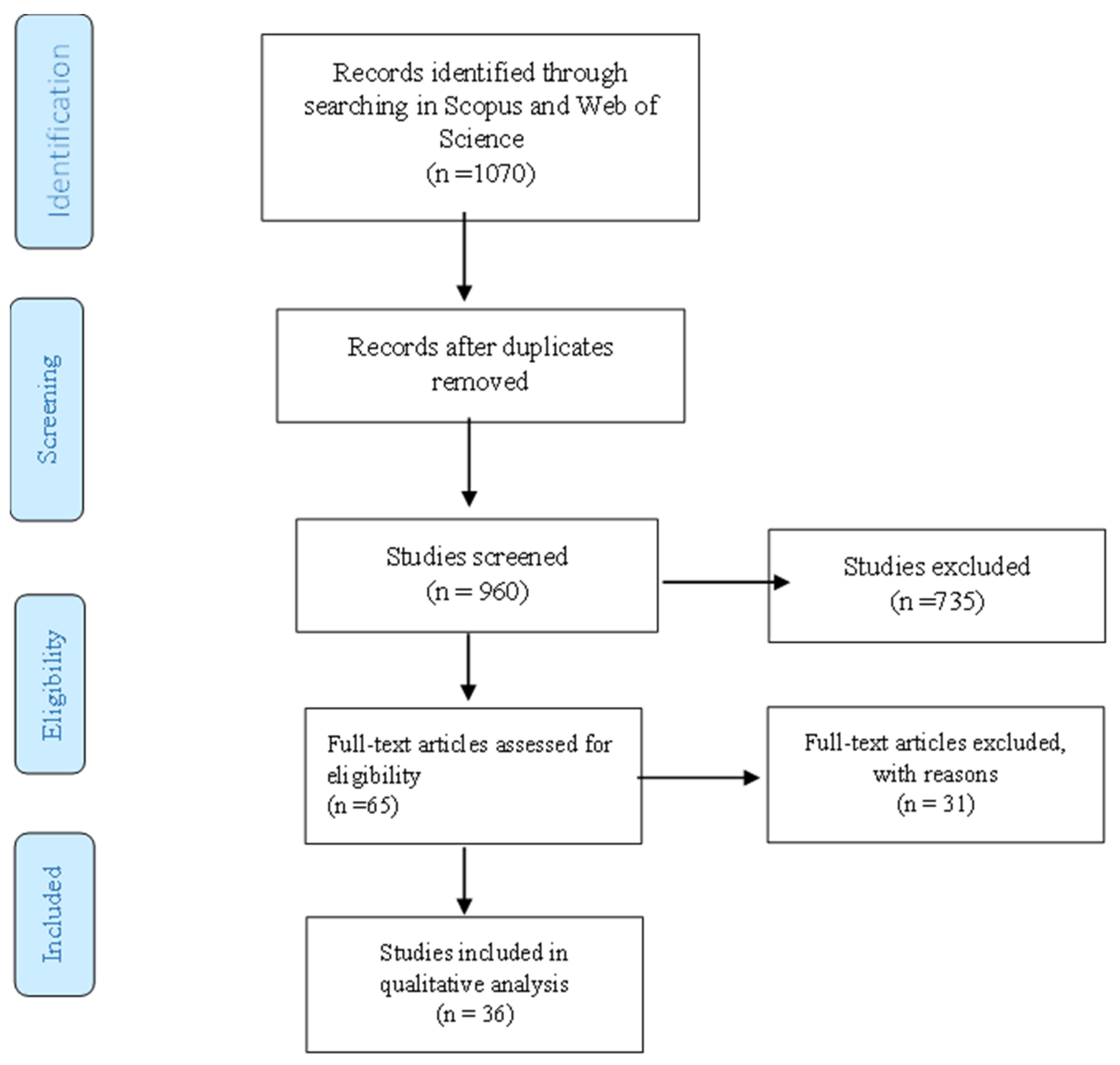

3. Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

4. Results

4.1. Macro Outlook Results

Volume and Geographic Distribution

4.2. Micro Outlook Results

Themes Identified

4.3. Theme 1: Educational Policy

4.4. Theme 2: Educational Leadership Models and Styles

4.5. Theme 3: Gender, Feminism and Social Justice

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Kaylani, Majid Irsan. 1981. Ibn Taymiya on Education: An Analytical Study of Ibn Taymiay’s Views on Education. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/61fd21371fc762935f11ddf630baae1b/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Al-Kaylani, Majid Irsan. 1985. The Development of the Concept of Islamic Educational Theory, 2nd ed. Medina: Dar Al-Turath Library, (Arabic). [Google Scholar]

- Altman, Yochanan. 2010. In search of spiritual leadership: Making a connection with transcendence. Human Resource Management International Digest 18: 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, Khalid, and Kussai Haj-Yehia. 2018. Perceptions of educational leadership in medieval Islamic thought: A contribution to multicultural contexts. Journal of Educational Administration and History 50: 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, Khalid Husny. 2015. Leadership for Equity and Social Justice in Arab And Jewish Schools in Israel: Leadership Trajectories and Pedagogical Praxis. International Journal of Multicultural Education 17: 162–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arar, Khalid Husny, and Izhar Oplatka. 2014. Muslim and Jewish Teachers’ Conceptions of the Male School Principal’s Masculinity: Insights into Cultural and Social Distinctions in Principal-Teacher Relations. Men and Masculinities 17: 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, Khalid Husny, and Tamar Shapira. 2016. Hijab and principalship: The interplay between belief systems, educational management and gender among Arab Muslim women in Israel. Gender and Education 28: 851–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, Khalid Husny. 2021. The Research on Refugees’ Pathways to Higher Education since 2010s: A Systemic Review. Review of Education 9: e3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, Khalid, Deniz Örücü, and Gülnur Ak Küçükçayır. 2019a. Culturally Relevant School Leadership for Syrian Refugee Students in Challenging Circumstances. Educational Management Administration & Leadership 47: 960–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, Khalid, Jeffrey S. Brooks, and Ira Bogotch. 2019b. Education, Immigration and Migration: Policy, Leadership and Praxis for Changing World. Bingley: Emerald. [Google Scholar]

- Arifin, I., Mustiningsih Juharyanto, and A. Taufiq. 2018. Islamic crash course as a leadership strategy of school principals in strengthening school organiza-tional culture. SAGE Open 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avolio, Bruce J., and William L. Gardner. 2005. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadership Quarterly 16: 315–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayagan, Y. S., S. K. Mediyeva, and J. B. Asetova. 2014. Muslim schools and madrasahs in new tendency on the basis of Islam culture in bukey horde re-formed by Zhanghir khan. Life Science Journal 11: 255–58. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Sally, Georgina Ramsay, and Caroline Lenette. 2019. Students from refugee and asylum seeker backgrounds and meaningful participation in higher education: From peripheral to fundamental concern. Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning 22: 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, Stephen J. 1998. Big Policies/Small World: An introduction to international perspectives in education policy. Comparative Education 34: 119–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banks, J. A., ed. 2017. Citizenship Education and Global Migration: Implications for Theory, Research, and Teaching. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bano, Massoda. 2014. Madrasa reforms and Islamic modernism in Bangladesh. Modern Asian Studies 48: 911–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, Andrew, Diana Papaioannou, and Anthea Sutton. 2012. Systematic Approaches to Successful Literature Review. Newcastle upon Tyne: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Melanie C. 2015. School principals in Southern Thailand: Exploring trust with community leaders during conflict. Educational Management Admin-istration and Leadership 43: 232–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Melanie C., and Agus Mutohar. 2018. Islamic school leadership: A conceptual framework Islamic school leadership: A conceptual framework. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Melanie C., and Miriam Deborah Ezzani. 2017. “Being Wholly Muslim and Wholly American”: Exploring One Islamic School’s Efforts to Educate against Extrem-ism. Teachers College Record 119: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Melanie C., and Miriam Deborah Ezzani. 2021. Islamic school leadership: Advancing a framework for critical spirituality. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 2021: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Melanie C., Jeffrey S. Brooks, Agus Mutohar, and Imam Taufiq. 2020. Principals as socio-religious curators: Progressive and conservative approaches in Islamic schools. Journal of Educational Administration 58: 677–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, Tony, and Derek Glover. 2014. School leadership models: What do we know? School Leadership and Management 34: 553–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, Kathryn, Shamshad Ahmed, and Mary Salvaterra. 2013. The rise of Islamic schools in the United States. Innovation Journal 18: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dent, Eric B., M. E. Higgins, and Deborah M. Wharff. 2005. Spirituality and leadership: An empirical review of definitions, distinctions, and embedded assump-tions. Leadership Quarterly 16: 625–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, Geert, and Michael S. Merry. 2006. Islamic schools in The Netherlands: Expansion or marginalization? Interchange 37: 201–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzani, Miriam, and Miriam Brooks. 2019. Culturally relevant leadership: Advancing critical consciousness in American Muslim students. Educational Administration Quarterly 55: 781–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, Matthew E., Eleni I. Pitsouni, George A. Malietzis, and Georgios Pappas. 2008. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. The FASEB Journal 22: 338–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, Louis W., Steve Vitucci, and Marie Cedillo. 2005. Spiritual leadership and army transformation: Theory, measurement, and establishing a baseline. The Leader-ship Quarterly 16: 835–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertzen, B. J., and J. E. Barbuto. 2001. Individual spirituality: A review of the literature. Submitted to Human Relations. Paper presented at Annual Institute for Behavioral and Applied Management, Denver, CO, USA, April 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, Philip, and Jasna Kovačević. 2019. A Bibliometric review of research on educational administration: Science mapping the literature. 1960 to 2018. Review of Educational Research 89: 335–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, Philip, and Waheed Hammad. 2019. Knowledge production on educational leadership and management in Arab societies: A systematic review of research. Educational Management Administration and Leadership 47: 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, Waheed, and Saeeda Shah. 2019. Leading faith schools in a secular society: Challenges facing head teachers of Muslim schools in the United Kingdom. Edu-Cational Management Administration and Leadership 47: 943–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadağ, Mehmet, Fahriye Altınay Aksal, Zehra Altınay Gazi, and Gökmen Dağli. 2020. Effect Size of Spiritual Leadership: In the Process of School Culture and Academic Success. SAGE Open 10: 215824402091463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khalil, Deena, and Amaarah DeCuir. 2018. This is us: Islamic feminist school leadership. Journal of Educational Administration and History 50: 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Adalat. 2007. Islamic Leadership: A Success Model for Everyone and All Times. Available online: http://americanchronicle.com/articles/view/33073 (accessed on 5 January 2009).

- Malla, H. A. B., M. T. Sapsuha, and S. Lobud. 2020. The influence of school leadership on Islamic education curriculum: A qualitative analysis. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change 11: 317–24. [Google Scholar]

- Maxcy, Brendan D., Ekkarin Sungtong, and Thu Suong Thi Nyguyen. 2010. Challenging school leadership in Thailand’s southern border provinces. Educational Management Administration and Leadership 38: 164–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, M. S., and Geert Driessen. 2016. On the right track? Islamic schools in The Netherlands after an era of turmoil. Race Ethnicity and Education 19: 856–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, Michael S., and G. Driessen. 2005. Islamic schools in three western countries: Policy and procedure. Comparative Education 41: 411–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertkan, S., N. Arsan, G. Inal Cavlan, and G. Onurkan Aliusta. 2017. Diversity and equality in academic publishing: The case of educational leadership. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 47: 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, and Douglas G. Altman. 2010. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 8: 336–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mongeon, Philippe, and Adèle Paul-Hus. 2016. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106: 213–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslih, Muslih. 2019. Islamic schooling, migrant Muslims and the problem of integration in The Netherlands. British Journal of Religious Education 43: 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oplatka, Izhar. 2010. The Legacy of Educational Administration: A Historical Analysis of an Academic Field. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Oplatka, Izhar, and Khalid Arar. 2017. The research on educational leadership and management in the Arab world since the 1990s: A Systematic Review. Review of Education 5: 267–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Jaddon, and Sarfaroz Niyozov. 2008. Madrasa education in South Asia and Southeast Asia: Current issues and debates. Asia Pacific Journal of Education 28: 323–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reave, Laura. 2005. Spiritual values and practices related to leadership effectiveness. Leadership Quarterly 16: 655–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissanen, Inkeri. 2019. School principals’ diversity ideologies in fostering the inclusion of Muslims in Finnish and Swedish schools. Race Ethnicity and Education, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saada, Najwan, and Haneen Magadlah. 2020. The meanings and possible implications of critical Islamic religious education. British Journal of Religious Education, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamun, Waheed, and Saeeda Shah. 2012. Investigating the concept of Rabbani leadership practices at secondary schools in Malaysia. Business & Management Quarterly Review 3: 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Saeeda. 2016. Education, Leadership and Islam: Theories, Discourses and Practices from Islamic Perspectives. Abington: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shakeel, M. Danish. 2018. Islamic schooling in the cultural west: A systematic review of the issues concerning school choice. Religions 9: 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sholikhah, Zahrotush, Xuhui Wang, and Wenjing Li. 2019. The role of spiritual leadership in fostering discretionary behaviors: The mediating effect of organization based self-esteem and workplace spirituality. International Journal of Law and Management 61: 232–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striepe, Michelle, S. Clarke, and T. O’Donoghue. 2014. Spirituality, values and the school’s ethos: Factors shaping leadership in a faith-based school. Issues in Educational Research 24: 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Suddahazai, Imran Hussain Khan. 2021. The development of leadership through islamic education: An empirical inquiry into religiosity and the styles of educational leadership experienced. International Journal of Education 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukowati, P., A. I. Zunaih, S. H. Jatmikowati, and V. Nelwan. 2019. Kiai leadership model in the development strategy of the participants. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering 8: 579–86. [Google Scholar]

- Syafiq Humaisi, M., Muhammad Thoyib, Imron Arifin, Ali Imron, and A. Sonhadji. 2019. Pesantren education and charismatic leadership: A qualitative analysis study on quality improvement of islamic education in pondok pesantren nurul jadid paiton, probolinggo. Universal Journal of Educational Research 7: 1509–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, Lokman Mohd, Aqeel Khan, Mohammed Borhandden Musah, Roslee Ahmad, Khadijah Daud, Shafeeq Hussain Vazhathodi Al-Hudawi, A. H. Musta’Amal, and R. Talib. 2018. Administrative stressors and islam-ic coping strategies among muslim primary principals in Malaysia: A Mixed Method Study. Community Mental Health Journal 54: 649–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolchah, Moch. 2014. The political dimension of Indonesian Islamic education in the post-1998 reform period. Journal of Indonesian Islam 8: 284–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Umar, Azizi, Ezad Azraai Jamsari, Wan Zulkifli Wan Hassan, Adibah Sulaiman, Nazri Muslim, and Zulkifli Mohamad. 2012. Appointment as principal of government-aided religious school (SABK) in Malaysia. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 6: 417–23. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, Nasir, A. R. Murniati, and Z. Ulfah Irani. 2021. Spiritual leadership management in strengthening the character of students in integrated Islamic primary schools. In 4th International Conference on Research of Educational Administration and Management (ICREAM 2020). Paris: Atlantis Press, pp. 421–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walford, Geoffrey. 2003. Separate schools for religious minorities in England and The Netherlands: Using a framework for the comparison and evaluation of policy. Research Papers in Education 18: 281–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Journal Name | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| Religions | 3 |

| British Journal of Religious Education | 3 |

| Educational Management, Administration and Leadership | 3 |

| Journal of Education Administration and History | 2 |

| Race, Ethnicity and Education | 2 |

| Study | Number of Times Mentioned |

|---|---|

| The role of spiritual leadership in fostering discretionary behaviors | 136 |

| Administrative stressors and Islamic coping strategies among Muslim primary principals in Malaysia: A mixed method study | 10 |

| Islamic schooling in the cultural west: A systematic review of the issues concerning school choice | 7 |

| Islamic crash course as a leadership strategy of school principals in strengthening school organizational culture | 6 |

| Leading faith schools in a secular society: Challenges facing head teachers of Muslim schools in the United Kingdom | 6 |

| Madrasa education in South Asia and Southeast Asia: Current issues and debates | 6 |

| The rise of Islamic schools in the United States | 6 |

| Muslim schools and madrasahs in new tendency on the basis of Islam culture in bukey horde reformed | 3 |

| This is us: Islamic feminist school leadership | 3 |

| Culturally relevant leadership advancing critical consciousness in American Muslim students | 2 |

| Islamic school leadership: A conceptual framework | 1 |

| A model for Islamic education from Turkey: The Imam-Hatip schools | 1 |

| Author(s) | Year | Country | Purpose(s) | Theme’s | Tools and Participants | Methodology Data Analysis | Journal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfarisi, S. & Efendi, N. | 2019 | Indonesia | Investigates the teacher’s role in performing leadership, supporting factors in leadership, and how school principals deals challenges | Kiai leadership, Islamic schools | Observation, interview, documentary, and questionnaire methods | Mix method analysis | International Journal on Integrated Education |

| Arar, K. & Oplatka, I. | 2014 | Israel | Examines views of Muslim and Jewish teachers in Israel regarding the masculinity of male school principals, and how these perceptions influence relationship between principals and teachers | Masculinity, Muslim, Jews, Israeli teachers, educational leadership | Semi-structured interview with 38 Muslim teachers and 31 Jewish teachers | Qualitative analysis | Men and Masculinities |

| Arar, L. & Shapira, T. | 2016 | Israel | Argues decision of Muslim female principals with hijab | Culture, Arab education, Israel, educational leadership | Interview with seven Muslim female principals wearing hihab | Qualitative case study analysis | Gender of Education |

| Arifin, I., Juharyanto, Mustiningsih, & Taufiq, A. | 2018 | Indonesia | Examines Nyantri (Islamic crash course) program as a leadership strategy in schools | Islamic crash course, Islamic leadership, school organizational culture | Observation, documentation, and in-depth interviews with principals, teachers, educational officers, and direct supervisors | Qualitative multicase analysis approach via theoretical phenomenology | Sage Open |

| Aşlamacı, I. & Kaymakcan, R. | 2017 | Turkey | Discusses Imam-Hatip schools in Turkey and their characteristic as a model of Islamic education. | Imam hatip high schools, Islamic education, Turkish Islamic education model | Historical review | Qualitative analysis | British Journal of Religious Education |

| Ayagan, Y. S., Mediyeva, S. K., & Asetova, J. B. | 2016 | Kazakhstan | Examines the educational policy of Russia in Kazakhstan | Muslim schools, religious education, Kazakhstan | Documents analysis | Qualitative analysis | On line scientific and Educational Bulletin “Health and Education Millennium" |

| Bano, M. | 2014 | United Kingdom | Explores the impact of state support at Islamic modern education in Bangladesh | State-aid schools, Bangladesh, madrasa, Islamic education | Interviews with officials of Bangladesh Madrasa Education | Qualitative analysis | Modern Asian Studies |

| Brooks, M & Mutohar, A. | 2018 | Australia | Reviewed Islamic educational leadership literature and created conceptual framework based the Islamic values and beliefs. | Islamic values, Islamic leadership, school leadership | Documents analysis | Qualitative analysis | Journal of Educational Administration and History |

| Brooks, M. | 2015 | U.S.A. | Aims to understand how Thai government school leaders establish and sustain trust with community leaders during times of conflict | Conflict, school leadership, Northern Thailand | Semi-structured interviews with twenty school principals | Qualitative case study analysis | Educational Management Administration &Leadership |

| Brooks, M. C., Brooks, J. S., Mutohar, A., & Taufiq, I. | 2020 | Australia | Examines how socio-religious factors influence school leaders in Islamic schools. | Principals, Indonesia, Islamic schooling, socio-religious thinking | Observations and semi-structured interviews with school leaders | Mix-method analysis | Journal of Educational Administration |

| Clauss, K., Ahmed, S., & Salvaterra, M. | 2013 | U.S.A | Explores purpose and function of Islamic schools in U.S from the perspective of Muslim school leaders, teachers, parents, and graduates. | American Muslims, Islamic education, identity, second and third generation Muslim students | Interviews with 25 individuals from parents, teachers, school leaders, and graduates | Qualitative analysis | The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal, Volume 18(1), 2013, article 4. |

| Dakir, F. | 2020 | Indonesia | Based on the ideal leadership model in Fatihah verses, reviews Islamic school leadership values and principles | Islamic leadership, Qur’anic based education | Library research | Qualitative analysis | Jurnal Pendidikan Islam (Islamic Education Journal) |

| Driessen, G., & Merry, M. S. | 2006 | The Netherlands | Investigates the function of the Islamic schools in The Netherlands such as their aim, performance, and the problems they face | Ethnic minorities, Muslims in The Netherlands, Islamic schools, Islamic education | Document analysis | Qualitative analysis | Interchange |

| Ezzani, M. & Brooks, M. | 2019 | U.S.A | Studies how principals of Islamic school in the United States perform culturally relevant leadership (CRL) | Culturally Relevant Leadership, Islamic school leadership, cultural syncretism | Interviews with teachers, students, and parents; classroom observations, and documents from institutions | Qualitative analysis | Educational Administration Quarterly |

| Hammad, W. & Shah, S. | 2018 | England | Aims to understand how the head teachers of Muslim schools experience leadership in the United Kingdom and what challenges they face | Leadership challenges, Muslim, religious schools | Semi-structured interviews with four head teachers of Muslim schools | Qualitative analysis | Educational Management Administration & Leadership |

| Hanafi, Y., Taufiq, A., Saefi, M., Ikhsan, M., Diyana, T., Thoriquttyas, T., Anam, F. | 2020 | Indonesia | Investigates the leadership practices of principals, school leaders, and teachers in Islamic boarding school (pesantren) regarding the new normal during the COVID-19 period | COVID-19, new normal, educational leadership, Pesantren education | Focus group interviews with teachers and principals | Content analysis | Heliyon |

| Humaisi, M., Arifin, I., Imron, A., & Sonhadji, A. | 2019 | Indonesia | Searches the charismatic leadership in Islamic education and how it affects the quality of educational outputs. | Charismatic Education, Islamic Education | In-depth interview, participant observation, and documentation | Qualitative case study analysis | Universal Journal of Educational Research |

| Khalil, D.& DeCuir, A. | 2018 | U.S.A | Investigates how Muslim female school leaders leading Islamic schools in America practice equity, community, and resistance | Islamic leadership, Islamic feminism, social justice, Islamic school | Interviews with 13 Muslim American women school leaders | Qualitative analysis | Journal of Educational Administration and History |

| Malla, H. A. B., Sapsuha, M. T., & Lobud | 2020 | Indonesia | Investigates principal leadership instruction for developing Islamic education of curriculum in Islamic senior high school | School leadership, Islamic education, curriculum | Principal, assistant principal, and students | Qualitative analysis | International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change |

| Maxcy, B. & Sungtong, E. | 2010 | Thailand | Explores the role of schools and school administrators within multiethnic society under Thailand’s neoliberal reform. | Islamic schooling, leadership, neoliberalism, Thailand | Interview with 12 principals | Qualitative analysis | Educational Policy |

| Maxcy, B. D., Sungtong, E., & Nguyên, T. S. | 2010 | Thailand | Discusses the challenges that principals face in public school of southern Thailand | Buddhist, Muslim, reform, school leadership, southern Thailand | Systematic review of interviews and government documents | Qualitative analysis | Educational Management Administration & Leadership |

| Merry, M. & Driessen, G. | 2015 | The Netherlands | Related to factors such as parental motivations, the teacher qualification, and school boards, performing of Islamic schools was investigated | Islamic schools in The Netherlands, primary education | National COOL cohort study | Quantitative analysis | Race Ethnicity and Education |

| Muslih, M. | 2021 | Indonesia | Discusses how well Islamic primary schools support their Muslim immigrant students both physically and mentally for integration into Dutch society | Islamic primary school, integration onto school environment, Muslims in Dutch | Document analysis | Qualitative analysis | British Journal of Religious Education |

| Park, J., & Niyozov, S | 2008 | Canada | Examines madrasa education and the challenges that Islamic schools face across South Asia and Southeast Asia | Islamic education, madrasa, Southeast Asia | Reviewed over 90 articles | Meta analysis | Asia Pasific Journal of Education |

| Prasetyo, M. | 2021 | Indonesia | Explores the effects of transformative leadership and organizational climate among teacher’s performance of Sholahuddin Gayo Lues Islamic Boarding School | Organizational climate, teacher’s performance, transformational leadership | Survey with 39 respondents | Quantitative analysis | Jurnal Manajemen, Kepemimpinan, dan Supervisi Pendidikan |

| Raihani | 2017 | Thailand | Analyzes leadership practices in different Islamic schools in Southern Thailand under the current ethno-political conflict between the Muslims and the Tai Buddhist government | Islamic school leadership, conflict area, strategic Leaders, Southern Thailand | Observation and interviews with six students and teachers | Multiple case study analysis | Indonesian Journal if Islamic Studies |

| Rissanen, I. | 2019 | Finland | Examines Finnish and Swedish principals’ diversity ideologies in Muslim students inclusion and how Finnish and Swedish principals’ differ in diversity ideologies | Culturally responsive education, diversity, Muslims, Finland, Sweden, leadership, inclusion | Interview with twenty principals and assistant principals | Qualitative analysis | Race Ethnicity and Education |

| Shah, S. | 2005 | United Kingdom | How learners from diverse backgrounds perceive educational leadership, receive education, and relate their learning experiences to the daily performance | Muslim women leaders, educational leadership, multi-ethnic society | Documentary review | Qualitative analysis | British Educational Research Journal |

| Shakeel, D. | 2018 | U.S.A. | Reviews the literature on Islamic schooling in Western countries based on the three issues; the purpose Islamic schooling, parental reason, the quality of school | Islamic schools, Muslim students in West, public and private schools | Systematic analysis | Mixed method analysis | Religions |

| Suddahazai, I. | 2021 | United Kingdom | Understands the relationship between the religiosity and the educational leadership styles of graduates of Muslim Institutes of Higher Education in the UK | Islamic education, religiosity, leadership style, Islamic boarding schools | Muslim Subjectivity Interview Schedule (MSIS), Semi- Structured Interviews (SSI), and Focus Group Discussions | Single case design | International Journal of Education and Learning |

| Sukowati, P., Zunaih, A. I., Jatmikowati, S. H., & Nelwan, V. | 2019 | Indonesia | Examines the role of Kiai leadership in Islamic boarding school | Kiai Leadership Style, Islamic schools | Interviews with school leaders, teachers, and students, observations, data analyses | Qualitative case study analysis | International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering |

| Syafiq Humaisi, M., Thoyib, M., Arifin, I., Imron, A., & Sonhadji, A. | 2019 | Indonesia | Aimed to explore and analyse the role of charismatic leadership in improving of the quality of Islamic education, the supervising quality, and the quality of educational outputs. | Charismatic Leadership, Islamic education | In-depth interview, participant observation, and documentation | Qualitative case study analysis | Universal Journal of Educational Research |

| Tahir, L. M., Khan, A., Musah, M. B., Ahmad, R., Daud, K., Al-Hudawi, S. H. V., Musta’Amal, A. H., & Talib, R. | 2018 | Malaysia | Investigates stress experiences and coping strategies of Muslim school principals | Muslim principals, Islamic coping strategies, stress experience | Survey and interview with 216 school administrates | Mix method analysis | Community Mental Health Journal |

| Tolchah, M. | 2014 | Indonesia | Explores educational policies in Indonesian Islamic Education within its political dynamics | Islamic education, educational policies, Indonesian Islamic education | Cultural analysis | Qualitative analysis | Journal of Indonesian Islam |

| Umar, A., Jamsari, E. A., Hassan, W. Z. W., Sulaiman, A., Muslim, N., & Mohamad, Z | 2012 | Malaysia | Examines the role of of principals in government-aided Islamic school (SABK) | Islamic education, government aided islamic schools | Document analysis and Interviews with officers | Mix-method | Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences |

| Walford, G. | 2003 | U.K. | Regarding the evaluation of policies, the study argues the differences in the implication of the educational policies of Muslim and Christian schools in England and The Netherlands | Religious schools, Muslim; Christian, England, The Netherlands | Documentary work, observation and interviews with school staffs and government officials | Mix method analysis | Research Papers in Education |

| Sub-Theme | No. of Papers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Faith-based leadership | 4 | 40 |

| Charismatic leadership (2) | ||

| Spiritual leadership (2) | ||

| Community engaged | 4 | 40 |

| Cultural relevant leadership (3) | ||

| Democratic leadership (1) | ||

| Strategic leadership | 2 | 20 |

| Sum | 10 | 100 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arar, K.; Sawalhi, R.; Yilmaz, M. The Research on Islamic-Based Educational Leadership since 1990: An International Review of Empirical Evidence and a Future Research Agenda. Religions 2022, 13, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010042

Arar K, Sawalhi R, Yilmaz M. The Research on Islamic-Based Educational Leadership since 1990: An International Review of Empirical Evidence and a Future Research Agenda. Religions. 2022; 13(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleArar, Khalid, Rania Sawalhi, and Munube Yilmaz. 2022. "The Research on Islamic-Based Educational Leadership since 1990: An International Review of Empirical Evidence and a Future Research Agenda" Religions 13, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010042

APA StyleArar, K., Sawalhi, R., & Yilmaz, M. (2022). The Research on Islamic-Based Educational Leadership since 1990: An International Review of Empirical Evidence and a Future Research Agenda. Religions, 13(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010042