Christian Accommodative Mindfulness: Definition, Current Research, and Group Protocol

Abstract

:1. Introduction

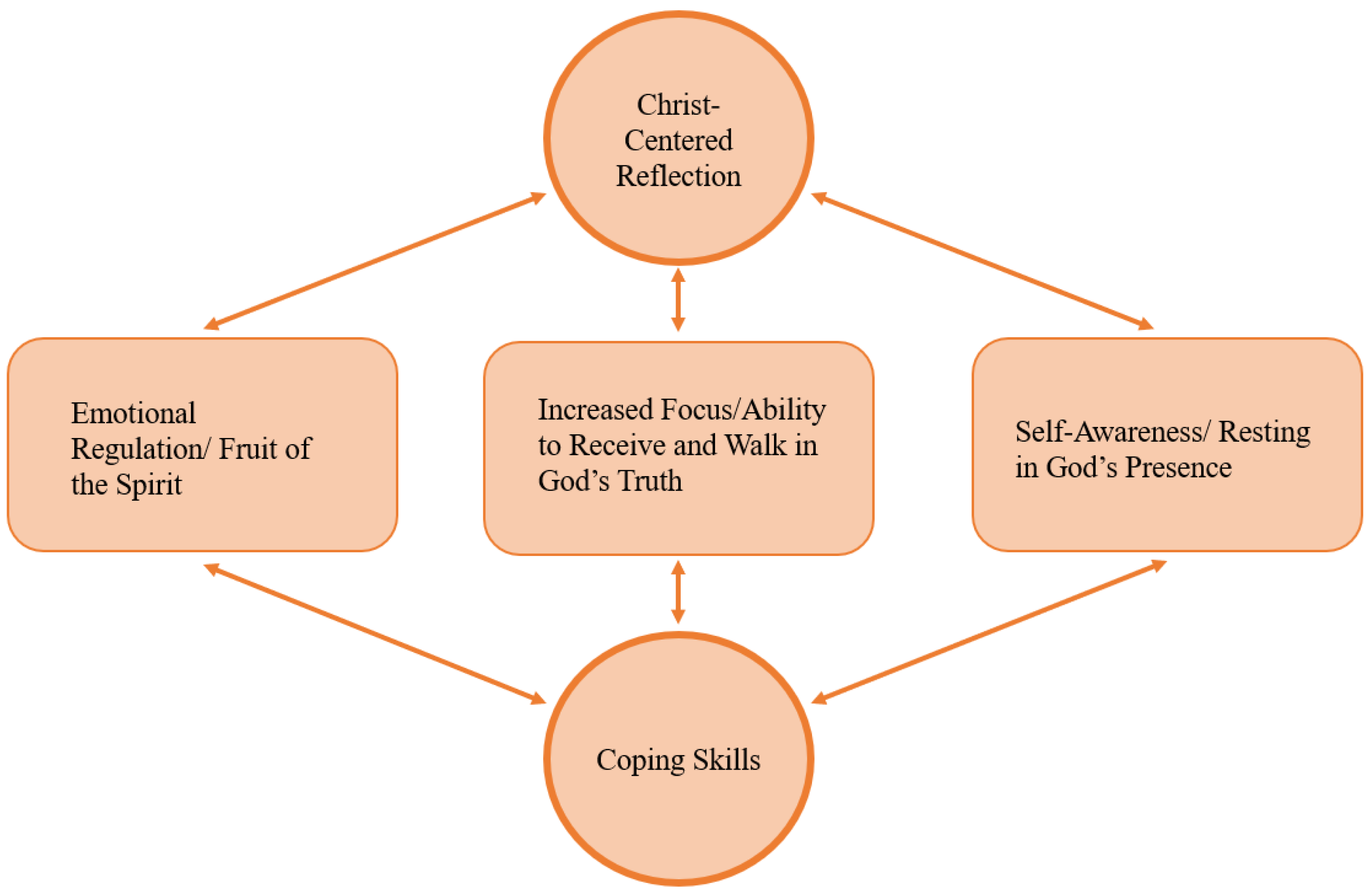

2. Current Definitions of Christian Mindfulness

3. Applying a Christian Worldview to Mindfulness Constructs

4. Empirical Research on CAM

4.1. Christian-Derived Studies

4.2. Adapted Mindfulness Studies

4.3. Summary of the Current CAM Outcomes-Based Literature

5. Group Protocol with Example Scripts

I’d like you to sit comfortably with your feet on the floor and your eyes closed or find a comfortable spot in the room to focus on. Notice the sounds in the room. What three sounds do you hear?…Begin to turn your awareness to your body. Feel how you’re sitting in the chair...how your hips feel on the chair. Notice how your hands are positioned and how they feel…Observe how your back feels...If your mind wanders, that’s okay. That’s just what minds do. Just bring yourself back to the meditation. Observe how your clothes feel on your shoulders…Notice how your face feels…See if you can sense any differences in temperature with how the air feels around your face, perhaps some places are cooler than others…Feel your feet in your shoes pressing against the floor…Notice your clothes against your legs…Just be aware of your experience, what is happening right now in this moment…while you’re observing this experience, I invite you to become aware of God’s presence with you today, that He’s here with you and wants to care for you in your experience.

I invite you to yield all you are experiencing to the Lord in this moment....Let go in His presence, releasing your tensions, thoughts, and worries into His hands. Jesus says “Come unto me, all of you who are weak and heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” Just be with God…As we close this activity, perhaps you would like to close with a quiet prayer. And when you’re ready, open your eyes.

This exercise is designed to help you connect with God in a way that invites warmth and goodwill into your life. Sit in a comfortable position, close your eyes or find a spot to rest your eyes comfortably in the room. Allow your mind and body to settle with a few deep breaths. Put your hands over your heart to remind yourself that you are bringing not only attention, but loving attention, to your experience. If this position is uncomfortable for you, you may choose to place your hands in your lap or by your side, whichever is more restful for you. For a few minutes, feel the warmth of your hands and their gentle pressure over your heart. Allow yourself to be soothed by the rhythmic movement of your breath beneath your hands… Now bring to mind a person who naturally makes you smile. This could be a friend, a close family member, whoever brings happiness to your heart. Feel what it’s like to be in that person’s presence. Allow yourself to enjoy the good company.

Next, recognize how vulnerable this loved one is—just like you, subject to many difficulties in life. Also, this person wishes to be happy and free from suffering, just like you and every other person. Repeat these prayers softly and gently to God, allowing the significance of your words to resonate in your heart… May this person be safe in Your love… May Your Spirit guide them… May You grant them peace… May Your Spirit renew them… May this person [substitute name if in individual therapy] find shelter in Your presence. Should you notice that your mind has wandered, return to the image of your loved one. Savor any warm feelings that may arise. Go slowly. Repeat these prayers again to God, allowing the words to resonate within… May this person be safe in Your love… May Your Spirit guide them… May You grant them peace. May Your Spirit renew them… May this person find shelter in Your presence. If you notice any discomfort, let it linger in the background and return to the phrases, or refocus on your loved one or your breath… Now visualize your own body in your mind’s eye, noticing any sensations, just as they are. Notice any discomfort or uneasiness that may be there.

Let’s continue these prayers to God but this time, the prayers will be about yourself. Listen to the following prayers and repeat them after you hear them read—if one resonates more for you, use that one. What do you need to hear right now?... May I be safe in Your love… May Your Spirit guide me… May You grant me peace… May Your Spirit renew me… May I find shelter in your presence. It is normal to feel a slight uneasiness or discomfort when using loving-kindness toward yourself. If these feelings come up for you, simply notice them and return your attention to the present moment as we repeat these prayers again… May I be safe in Your love… May Your Spirit guide me… May You grant me peace… May Your Spirit renew me… May I find shelter in your presence. If you notice any discomfort, let it linger in the background and return to the prayers, or refocus on your loved one or your breath. Remember to continue breathing deeply. Again, visualize your own body in your mind’s eye and feel any sensations that may arise. If any discomfort or uneasiness is there, just notice it without judgment.

As we come to the end of the meditation, take a moment to reflect on this feeling of loving-kindness for yourself and your loved ones…….(pause) In a moment, the meditation will end. We hope that you leave this meditation with a sense of accomplishment and peace for practicing this act of compassion. Whenever you are ready, gently open your eyes and return your attention to the room.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chua, Joelle, Yan Xin, and Shefaly Shorey. 2021. The Effect of Mindfulness-Based and Acceptance Commitment Therapy-Based Interventions to Improve the Mental Well-Being Among Parents of Children with Developmental Disabilities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elices, Matilde, Joaquim Soler, Albert Feliu-Soler, Cristina Carmona, Thais Tiana, Juan C. Pascual, Azucena García-Palacios, and Enric Álvarez. 2017. Combining Emotion Regulation and Mindfulness Skills for Preventing Depression Relapse: A Randomized-Controlled Study. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation 4: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, Robert A., Peter C. Hill, Justin L. Barrett, and Kelly M. Kapic. 2017. Psychological and Theological Reflections on Grace and its Relevance for Science and Practice. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 9: 276–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Jane K., Eleanor W. Willemsen, and MayLynn V. Castañeto. 2010. Centering Prayer as a Healing Response to Everyday Stress: A Psychological and Spiritual Process. Pastoral Psychology 59: 305–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, Kristy, and Fernando Garzon. 2017. Research Note: A Randomized Investigation of Evangelical Christian Accommodative Mindfulness. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 4: 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, Thomas, and Kristen M. White. 2015. Mindfulness, Christian Devotion Meditation, Surrender, and Worry. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 18: 850–58. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, Thomas V., Scott Dunbar, and Yvonne Thai. 2017. Burnout in Christian Perspective. Pastoral Psychology 67: 267–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, Fernando. 2013. Christian devotional meditation for anxiety. In Evidence-Based Practices for Christian Counseling and Psychotherapy. Edited by Jamie Aten, Eric Johnson, Everett Worthington and Joshua Hook. Downers Grove: Intervarsity Academic Press, pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Garzon, Fernando. 2015. Mindfulness or Christian Present Moment Awareness? Different Options with Different Results. AACC Newsletter: Christian Counseling Connection 20: 7. [Google Scholar]

- Garzon, Fernando, and Kristy Ford. 2016. Adapting Mindfulness for Conservative Christians. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 35: 254–59. [Google Scholar]

- Germer, Christopher, and Kristin Neff. 2019. Teaching the Mindful Self-Compassion Program. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, Philippe R., and James J. Gross. 2010. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) on Emotion Regulation in Social Anxiety Disorder. Emotion 10: 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Manuel, Ignacio Ibáñez, and Andrea Barrera. 2017. Rumination, Worry and Negative Problem Orientation: Transdiagnostic Processes of Anxiety, Eating Behavior and Mood Disorders. Acta Colombiana de Psicología 20: 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, Adam S., Joshua N. Hook, Don E. Davis, Daryl R. Van Tongeren, Rodger K. Bufford, Rodney L. Bassett, and Mark R. McMinn. 2020. Experiencing Grace: A Review of the Empirical Literature. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, Jonathan. 2018. Can Christians Practice Mindfulness Without Compromising Their Convictions? Journal of Psychology and Christianity 37: 247–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Eric L., Everett L. Worthington, Joshua N. Hook, and Jamie D. Aten. 2013. Evidence-Based Practice in Light of the Christian Tradition(s): Reflections and Future Directions. In Evidence-Based Practices for Christian Counseling and Psychotherapy. Edited by Everett L. Worthington, Eric L. Johnson, Joshua N. Hook and Jamie D. Aten. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Tracy L., Fernando L. Garzon, and Kristy M. Ford. 2021. Christian Accommodative Mindfulness in the Clinical Treatment of Shame, Depression, and Anxiety: Results of an N-of-1 Time-Series Study. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, Daniel K., Justin W. Dyer, and Justin B. Top. 2020. Grace, Legalism, and Mental Health: Examining Direct and Mediating Relationships. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 12: 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Uichol, Young-Shin Park, and Donghyun Park. 2000. The Challenge of Cross-Cultural Psychology: The Role of Indigenous Psychologies. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 31: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knabb, Joshua J. 2019. The Compassion-Based Workbook for Christian Clients: Finding Freedom from Shame and Negative Self-Judgments. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Knabb, Joshua J. 2021. Christian Meditation in Clinical Practice: A Four-Step Model and Workbook for Therapists and Clients. Downers Grove: Intervarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knabb, Joshua J., and Thomas V. Frederick. 2017. Contemplative Prayer for Christians with Chronic Worry: An Eight-Week Program. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Knabb, Joshua J., Thomas V. Frederick, and George Cumming. 2017. Surrendering to God’s Providence: A Three-Part Study on Providence-Focused Therapy for Recurrent Worry (PFT-RW). Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 9: 180–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knabb, Joshua J., Veola E. Vazquez, Fernando L. Garzon, Kristy M. Ford, Kenneth T. Wang, Kevin W. Conner, Steve E. Warren, and Donna M. Weston. 2020. Christian Meditation for Repetitive Negative Thinking: A Multisite Randomized Trial Examining the Effects of a 4-Week Preventative Program. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 7: 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knabb, Joshua J., Veola E. Vazquez, Kenneth T. Wang, and M. Todd Bates. 2018. “Unknowing” in the 21st Century: Humble Detachment for Christians with Repetitive Negative Thinking. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 5: 170–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knabb, Joshua J., Veola E. Vazquez, Robert A. Pate, Fernando L. Garzon, Kenneth T. Wang, DeAndra Edison-Riley, Alexandra R. Slick, Royalle R. Smith, and Sarah E. Weber. 2021. Christian Meditation for Trauma-Based Rumination: A Two-Part Study Examining the Effects of an Internet-Based 4-Week Program. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Marin, Jesus, Maria C. Perez-Yus, Ausias Cebolla, Joaquim Soler, Marcelo Demarzo, and Javier Garcia-Campayo. 2019. Religiosity and Meditation Practice: Exploring Their Explanatory Power on Psychological Adjustment. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, Mark. 2003. The Rise of Evangelicalism: The Age of Edwards, Whitfield, and the Wesleys. Downers Grove: Intervarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, M. Basil. 1986. Centered Living: The Way of Centering Prayer. Garden: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer, L. O., and S. M. Orsillo. 2009. Mindfulness and Acceptance-Based Behavioral Therapies in Practice. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinart, Marta, Albert Fornieles, and Joan Deus. 2017. The Psychological Impact of the Jesus Prayer among Non-Conventional Catholics. Pastoral Psychology 66: 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisemore, Timothy A., and Joshua J. Knabb. 2020. The Psychology of World Religions and Spiritualities: An Indigenous Perspective. West Conshohocken: Templeton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Symington, Scott H., and Melissa F. Symington. 2012. A Christian Model of Mindfulness: Using Mindfulness Principles to Support Psychological Well-Being, Value-Based Behavior, and the Christian Spiritual Journey. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 31: 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Yi-Yuan, Britta K. Holzel, and Michael I. Posner. 2015. The Neuroscience of Mindfulness Meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 16: 213–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trammel, Regina. 2018. Effectiveness of an MP3 Christian Mindfulness Intervention on Mindfulness and Perceived Stress. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 21: 500–14. [Google Scholar]

- Trammel, Regina, and John Trent. 2021. A Counselor’s Guide to Christian Mindfulness: Engaging the Mind, Body, and Soul in Biblical Practices and Therapies. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [Google Scholar]

- Trammel, Regina, Gewnhi Park, and Ian Karlsson. 2021. Religiously Oriented Mindfulness for Social Workers: Effects on Mindfulness, Heart Rate Variability, and Personal Burnout. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 40: 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Turgoose, David, Rachel Ashwick, and Dominic Murphy. 2018. Systematic Review of Lessons Learned from Delivering Tele-Therapy to Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 24: 575–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varker, Tracey, Rachel M. Brand, Janine Ward, Sonia Terhaag, and Andrea Phelps. 2019. Efficacy of Synchronous Telepsychology Interventions for People with Anxiety, Depression, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Adjustment Disorder: A Rapid Evidence Assessment. Psychological Services 16: 621–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhoit, James C. 2018. Self-Compassion as a Christian Spiritual Practice. Journal of Spiritual Formation and Soul Care 12: 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. Mark G., Ian Russel, and Daphne Russell. 2008. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy: Further Issues in Current Evidence and Future Research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 76: 524–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong-McDonald, Ana, and Richard L. Gorsuch. 2000. Surrender to God: An Additional Coping style? Journal of Psychology and Theology 28: 149–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | Goals | Outline |

|---|---|---|

| Participants will be oriented to thought–stress model, CAM, and scripture meditation |

|

| Participants will be oriented to the scriptural focus on the breath and present-moment awareness through breath meditation |

|

| Participants will be oriented to the relationship between the body and stress, what scripture has to say about the body and stress, and body awareness through a body scan meditation |

|

| Participants will discuss scriptural themes of grace and forgiveness, and cultivating loving-kindness toward self and others through loving-kindness meditation |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garzon, F.; Benitez-DeVilbiss, A.; Turbessi, V.; Offei Darko, Y.T.; Berberena, N.; Jens, A.; Wray, K.; Bourne, E.; Keay, J.; Jenks, J.; et al. Christian Accommodative Mindfulness: Definition, Current Research, and Group Protocol. Religions 2022, 13, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010063

Garzon F, Benitez-DeVilbiss A, Turbessi V, Offei Darko YT, Berberena N, Jens A, Wray K, Bourne E, Keay J, Jenks J, et al. Christian Accommodative Mindfulness: Definition, Current Research, and Group Protocol. Religions. 2022; 13(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarzon, Fernando, Andres Benitez-DeVilbiss, Vera Turbessi, Yaa Tiwaa Offei Darko, Nelsie Berberena, Ashley Jens, Kaitlin Wray, Erica Bourne, John Keay, Jeffrey Jenks, and et al. 2022. "Christian Accommodative Mindfulness: Definition, Current Research, and Group Protocol" Religions 13, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010063

APA StyleGarzon, F., Benitez-DeVilbiss, A., Turbessi, V., Offei Darko, Y. T., Berberena, N., Jens, A., Wray, K., Bourne, E., Keay, J., Jenks, J., Noble, C., & Artis, C. (2022). Christian Accommodative Mindfulness: Definition, Current Research, and Group Protocol. Religions, 13(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010063